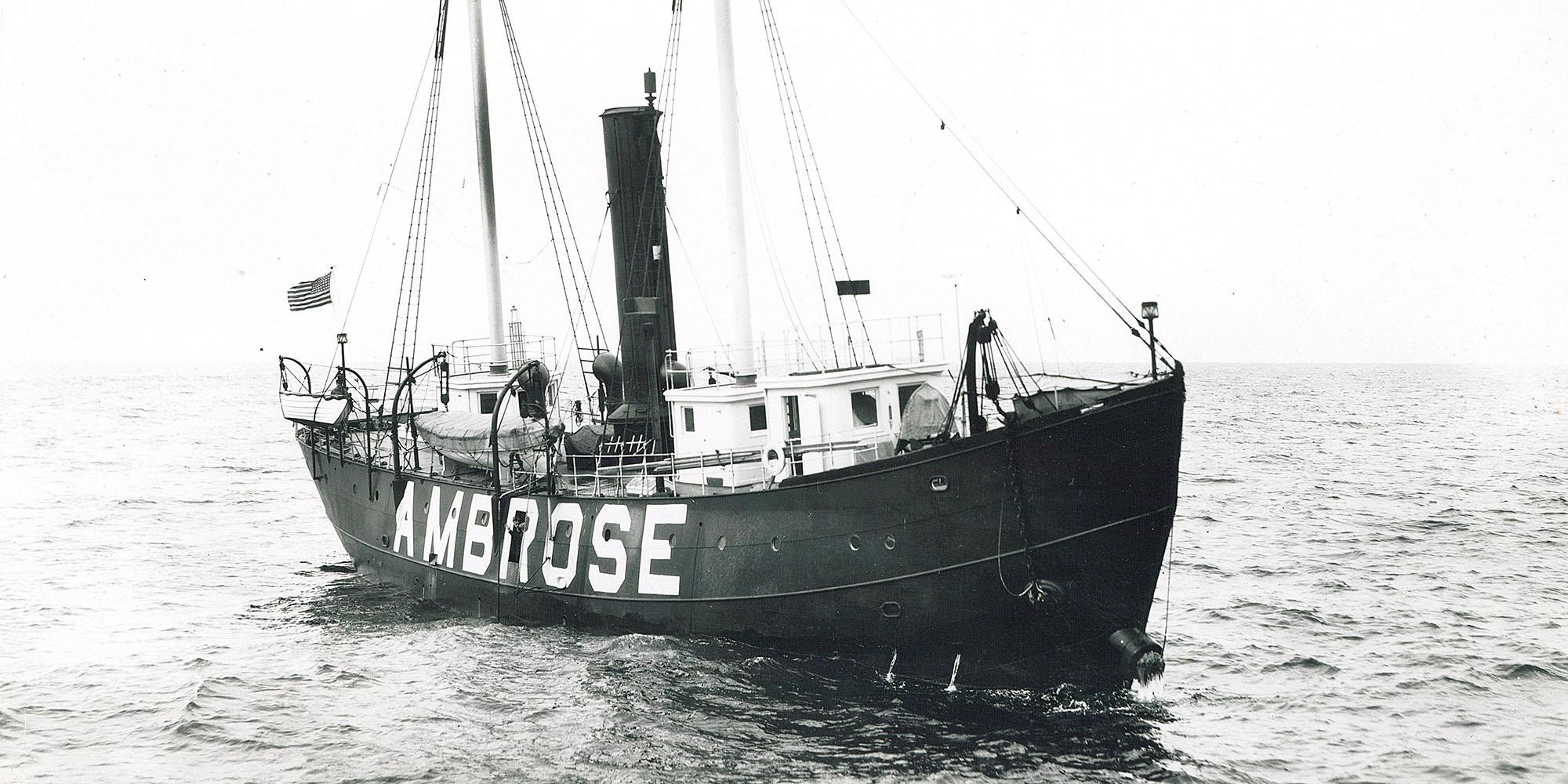

Lightship LV-87, commonly known as Ambrose, was built in 1907 as a floating lighthouse to guide ships safely from the Atlantic Ocean into the broad mouth of Lower New York Bay between Coney Island, New York, and Sandy Hook, New Jersey—an area filled with sand bars and shoals perilous to approaching vessels.

LV-87 occupied her original station from December 1, 1908 until 1932. During these 24 years, she guided mariners to the nation’s busiest port, the Port of New York. In her role as navigational aid, she witnessed the largest period of immigration in United States history, seeing over six million immigrants pass her station.

Ambrose remained on station through the worst storms and collisions with a number of vessels bound for or from New York. Serving on one of America’s most important lightship stations, she had a profound impact on local, coastal, and international trade.

After her half-century career, LV-87 was donated to the newly formed South Street Seaport Museum by the United States Coast Guard on August 5, 1968. At the Museum, Ambrose vividly recounts the story of sailors who worked and lived aboard historic lightships, shedding light on the vital role it played in shaping the development of New York as a bustling global city. LV-87 is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and a National Historic Landmark. In addition, the vessel highlights the significant influence of the immigrant experience on the city’s growth. As countless waves of immigrants arrived in New York seeking better opportunities, they brought with them diverse cultures, traditions, and skills that interwove to form the rich tapestry of the city’s identity—the very foundation of “Where New York Begins.”

The Ambrose Channel

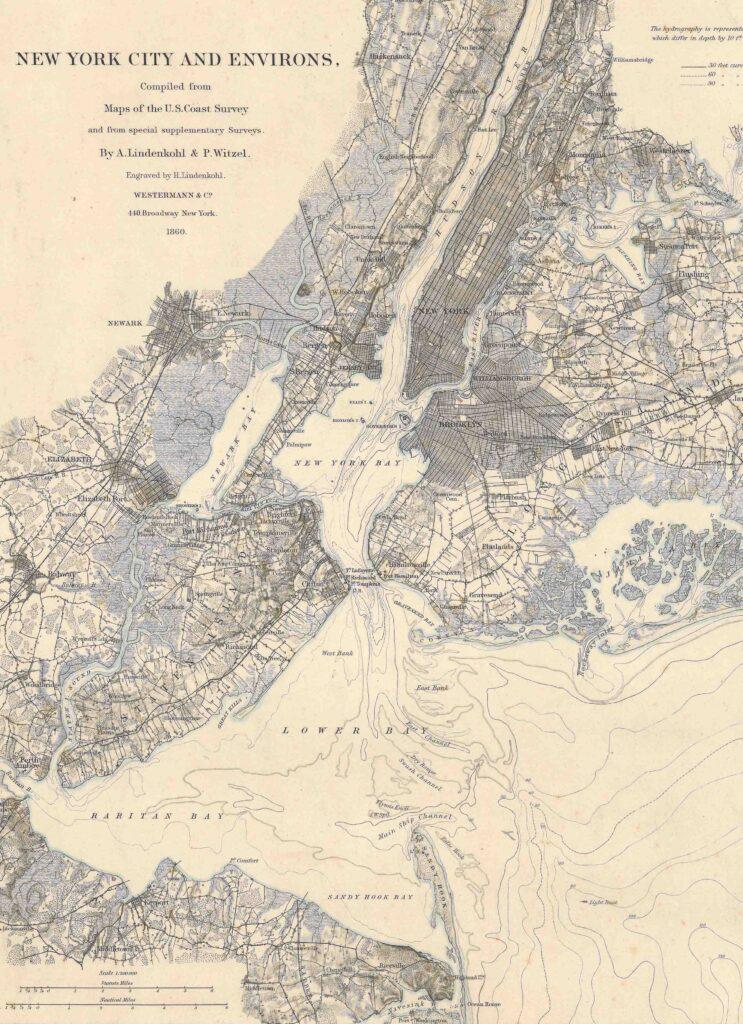

The Ambrose Channel is how large vessels—from cruise ships to cargo ships—enter and exit New York Harbor from the Atlantic Ocean. It is an early 20th century man-made channel in the Lower New York Bay, starting just south of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge and running between Sandy Hook, New Jersey and Breezy Point, Queens. Today, the channel is 53 feet deep, 2,000 feet wide, and over 15 miles long.

In the centuries before Ambrose Channel was excavated, naturally occurring channels were mapped, maintained, and deepened for ships navigating New York Harbor. With the development of metal-hulled and steam powered ships in the 19th century, vessels were being constructed with larger and larger hulls. By the end of the 19th century, the government was gradually deepening existing channels by a few feet every decade or so in order to accommodate the increasing size of ships. However, in order to secure New York’s place as one of the most important ports in the world, a more permanent solution was needed.

In 1899, after nearly 17 years of lobbying by New York City engineer and businessman John Wolfe Ambrose (1838–1899), Congress agreed to fund an entirely new channel with the “River and Harbor Act of 1899,” with an appropriation of $4,000,000.

Work began in 1901 under a private contractor, but did not progress as quickly as needed. In 1906, the project was taken over by the US Army Corps of Engineers and four dredges were built for the task. The Channel, along its original 7 miles, was completed in 1913. This massive civil engineering project excavated over 1.6 billion cubic feet of mud, sand, and stone at a cost of a little over $5,000,000.

Adolph Lindenkohl, cartographer; Peter Witzel, cartographer; Henry Lindenkohl, engraver; B. Westermann & Co., publisher. Detail from “New York City and Environs”, 1860. Museum Purchase 2001.003

In order for Ambrose Channel to be navigable as quickly as possible, the Channel opened to ships when it was only halfway completed. By 1907, the entire length of the Channel had been dredged at a depth of 40 feet, but at 1,000 feet it was only half as wide as planned. The first ship to officially enter New York Harbor via the Ambrose Channel was the ill-fated Cunard liner RMS Lusitania on her maiden voyage on September 13, 1907. Lightship Ambrose LV-87 would take her position marking the entrance to Ambrose Channel on December 1, 1908.

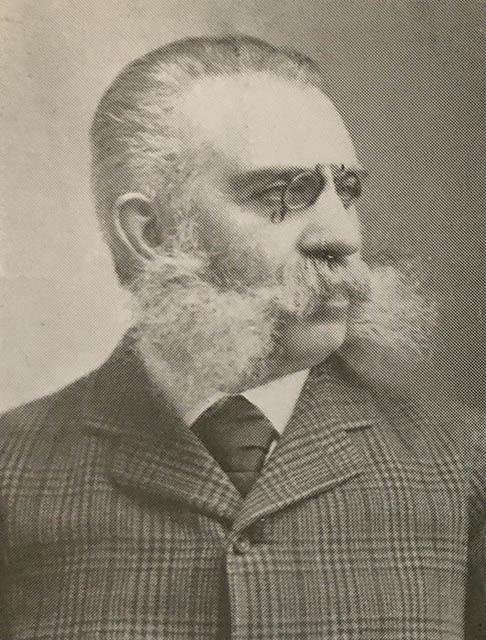

John Wolfe Ambrose

John Wolfe Ambrose was born on January 10, 1838 in New Castle, Ireland, and immigrated to the United States as a child with his family. He attended New York University and Princeton University and became an engineer and urban developer in New York City. He would be involved with several notable public projects including the building of the Second Avenue and Sixth Avenue elevated rails and the development of many streets in upper Manhattan.

Ambrose had been interested in the improvement of the Brooklyn waterfront, and in the 1880s became the president of the Brooklyn Wharf and Dry Dock Company. He recognized that harbor improvements were needed to sustain and grow New York City’s maritime industry—especially as ships were becoming too large for the depth of existing shipping channels. By 1883, Ambrose was lobbying Congress to fund a channel for the harbor since New York City was the country’s largest international port and was critical to the national economy.

“John Wolfe Ambrose”, excerpt from Valentine’s manual of the city of New York, 1920. South Street Seaport Museum Reference Library.

Ambrose would lobby Congress for over 16 years, facing opposition from representatives from other districts as well as from some local port businesses that were concerned accommodating the largest ships would divert trade to the few waterfront facilities that could handle them. Ambrose, with the support of Senator Thomas Platt and Senator William Frye, was able to secure the federal appropriation in 1898. Though New York City bigwigs wanted to throw a dinner in Ambrose’s honor, Ambrose refused the accolades and insisted the dinner be given for Senator Frye instead.

John W. Ambrose would not see his channel completed; he died on May 15, 1899 from typhoid and was buried in the Green-Wood Cemetery. A commemorative bust of Ambrose was erected in Battery Park in 1936, and the channel he worked so hard to actualize is named after him.

Lightship Names

Today, Ambrose LV-87 is painted red with her station name “AMBROSE” painted in large white letters along her sides. But, LV-87 wasn’t always red and her name wasn’t always “Ambrose.”

While “floating lights” for navigation along the North American coast have been used since the 1700s, it was in 1820 that lightships, as we know them today, were first employed in the United States. Lightships had no standard color scheme and they could be red, black, gray, green, yellow, or even have multi-colored checks and stripes. The standard colors for lightships—red hull, white letters, and buff smokestack—weren’t established until 1940.

The names of lightships are also subject to change, since the ships take the name of the station to which they are assigned. In 1944, when Ambrose Lightship LV-87 was reassigned to a new station in Vineyard Sound (off Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts), she was called Vineyard Sound, not Ambrose. This is why the Museum includes the number designation LV-87 when referring to this “Ambrose”—it lets us track this ship across her many stations and name changes and distinguishes her from the “Ambrose” lightships that succeeded her at the Ambrose Channel station.

LV-87 was commissioned by the US Lighthouse Board and built in 1907 at the New York Shipbuilding Co. in Camden, New Jersey, at a cost of over $100,000.

Constructed with a double-riveted steel hull and wood deckhouses, LV-87 was initially equipped with a steam engine and schooner-rigged sails, which are no longer extant.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch

From 1908–1929, when LV-87 served at the Ambrose Channel Station, the ship was painted a straw color (light yellow) with black lettering painted on both sides. Her color was changed in 1929 when she was painted black with white lettering. LV-87 would be stationed at Ambrose Channel until 1932 when she underwent a major refit where the engine, and much auxiliary equipment, was replaced.

Col. Walter R. Bruyere III (American, 1916–2004). “Lightship Ambrose” 1988. Wood, cloth, metal, paint. Gift of Walter Bruyere 1988.007

LV-87 returned to service in 1932 as a “relief” lightship, substituting for the permanent lightships of New York Harbor when they went in for maintenance or otherwise left their post. Her name was changed to Relief, and her hull was painted red.

In 1936, LV-87 was once again assigned to a permanent station off New York Harbor as the Scotland Lightship. Scotland Station was located to the west of Ambrose Station, off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and was primarily used as a navigation mark by north-south coastwise traffic heading to New York Harbor.

From 1942–1944, LV-87 was withdrawn from Scotland Station and was converted into an examination vessel. During World War II, many lightships were requisitioned by the US Navy for defense needs. Some lightship stations were replaced by lighted buoys or by relief vessels. LV-87 was armed with a 1 pounder naval gun and was tasked with inspecting vessels entering New York Harbor.

After the war, LV-87 left New York Harbor and was assigned to the Vineyard Sound Station off Martha’s Vineyard. LV-87 would only spend three years as Vineyard Sound before returning to New York as Scotland in 1947. She would remain Scotland until 1962.

Her career as an active lightship was over, but LV-87 was sent to the 1964 New York World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, where she served as an exhibit for the US Coast Guard. Following the Fair, she was laid up in Curtis Bay, Maryland, until 1968 when she was donated to the South Street Seaport Museum.

[Lightship Scotland at sea], mid 20th century. U.S. Coast Guard Photo, South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Life on Board

When lightship Ambrose LV-87 took her station in New York Harbor in 1908, there were 14 crew members: one master, one mate, two engineers, three firemen, six seamen, and one cook. However, the crew wouldn’t all be on the ship at the same time; crew members would have a shift lasting about three weeks and then have one week off. As a rule, when the master wasn’t on board, the mate had to be on board. In addition, one engineer and two firemen always had to be on board.

Compared to the wooden lightships of the 19th century, lightships like Ambrose LV-87 were designed with the comfort of the crew in mind. Early lightships were often not purpose-built for sitting at anchor as a fixed light platform and would roll and pitch with rough seas. When comparing the new Ambrose to the old LV-87 lightship, the new vessel was described as less of “a bucking bronco,” which must have been some relief to the crew living on board.

Other amenities for the crew included bath facilities, steam heated cabins, and a small library of books provided by the Lighthouse Service. Crew accommodations were in the fore of the ship, with two bunks per stateroom. The master, mate, and engineers had personal staterooms and an officers mess room in the aft.

Top Left: “Signals by hand motion how far to go with anchor, USS Relief, St. George Base, Staten Island”, February 28, 1945.

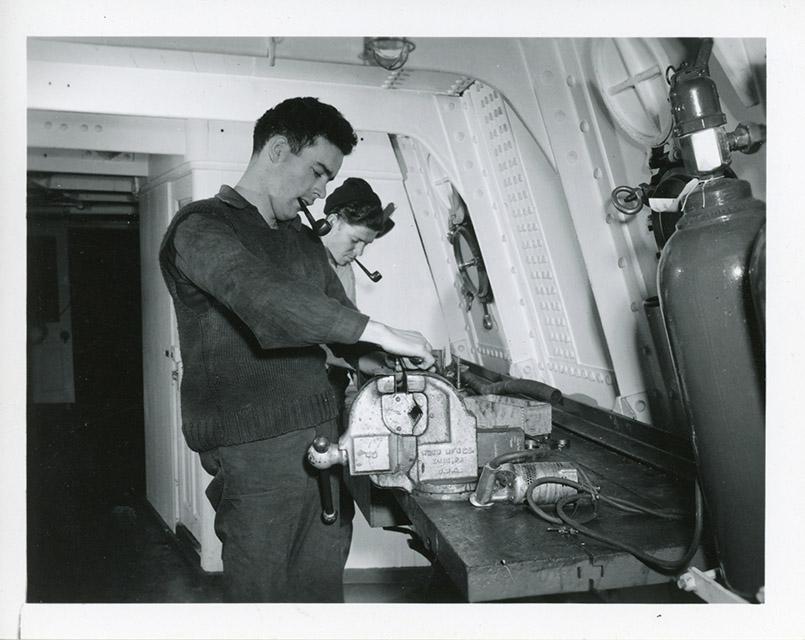

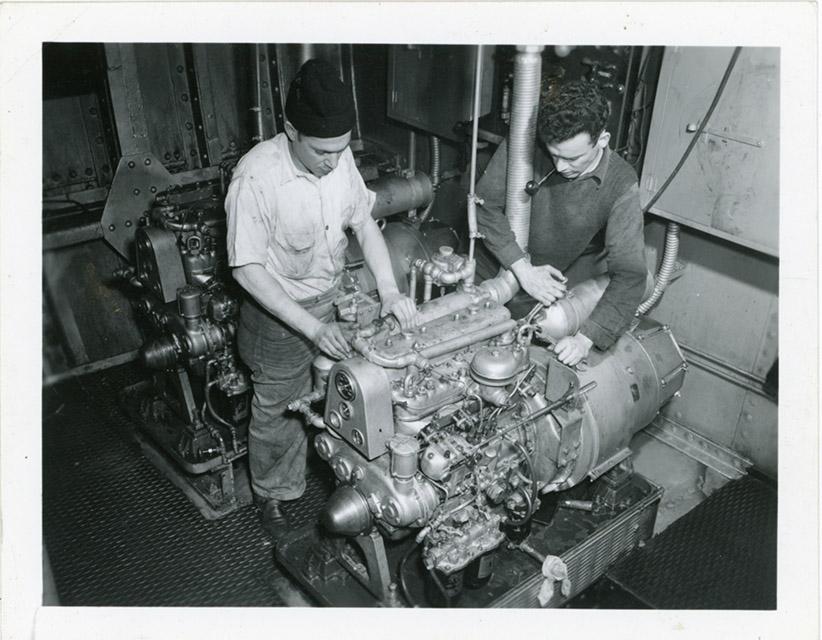

Top Right: “Two crew members repairing blower, USS Relief, St. George Base, Staten Island”, February 28, 1945.

Lower Left: “Checking anchor chain in chain locker, USS Relief, St. George Base, Staten Island”, February 28, 1945.

Lower Right: [Members of the crew of USS Relief working on machinery below decks, St. George Base, Staten Island], 1945.

While on board, the crew had to ensure the lightship would run smoothly. The lights, which other ships relied upon for safe navigation, had to be maintained. The whistle, foghorn, and later radio beacon were similarly cared for. When the ship was powered by steam, the engine boilers had to be stoked. Even after the ship was converted to diesel, the engine had to be oiled and “turned over” periodically. Annoyances that came with the job included repeatedly hearing the incredibly loud foghorn on foggy days and the pervasive smell of diesel fuel throughout the ship.

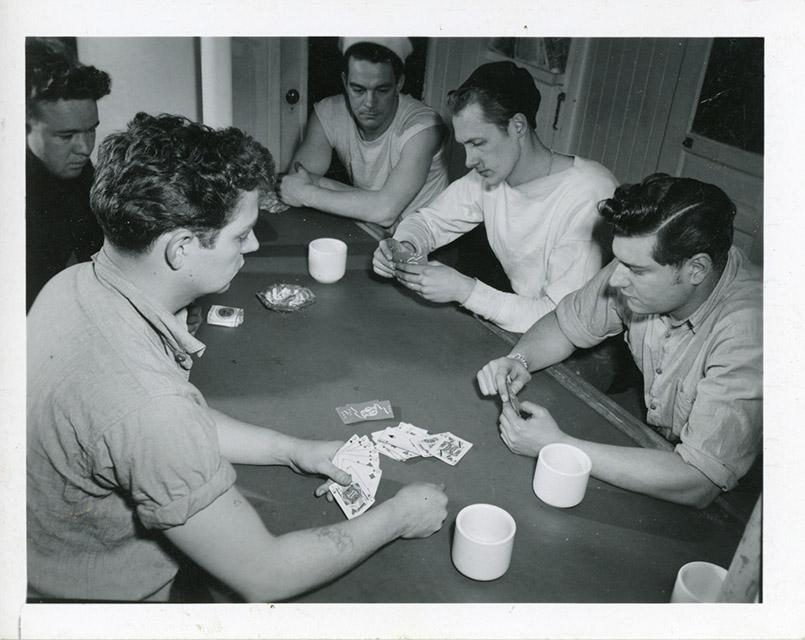

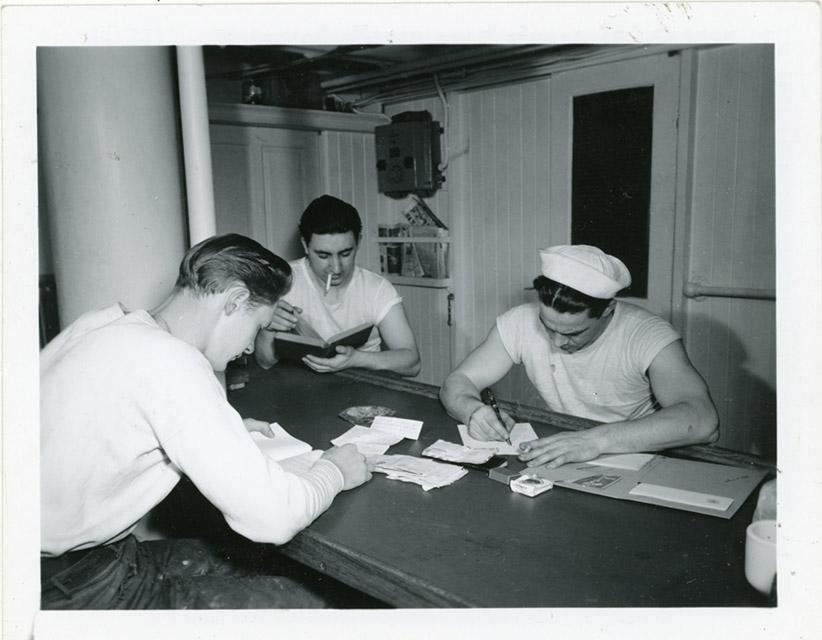

Though work on a lightship wasn’t easy, there would be a lot of time where the crew would have to entertain themselves. Boredom and isolation are often mentioned by contemporary reporters and lightship historians. Though Ambrose was stationed only a few miles from New York City, the crew were cut off from daily communication with the outside world. Later in the 20th century, lightship crews would have access to recorded music, commercial radio, and television while on board. Fishing off the side of the vessel and adopting a ship’s cat, or other “mascot,” were pastimes of the Ambrose crew.

Left: “Playing cards, USS Relief, St. George Base, Staten Island”, February 28, 1945.

Right: “Members of the crew writing letters and reading for pleasure, USS Relief, St. George Base, Staten Island”, February 28, 1945.

Despite the monotony, there were advantages to being a member of a lightship’s crew. In a 1912 newspaper article, Ambrose master Gustave Lange, who commanded the ship from 1908–1932, said that many men in the Lighthouse Service were older sailors who no longer wanted to go to sea, but ˆwanted a steady paycheck and other benefits that came from government employment.

Food on board a lightship was not the most varied—especially in the decades before refrigeration. An 1891 article[1]”Life on the South Shoal Lightship” by Gustav Kobbé, Century Magazine, August 1891. about life on a lightship off of Nantucket stated that the food was wholesome but monotonous, often composed of salted beef, onions, and potatoes. A different article about Ambrose Lightship LV-87 from 1912[2]”The Non-Sailing Sailors Who Man Craft-Warning Craft Along the Coast”, New-York Tribune, October 20, 1912. notes that the tender would bring fresh vegetables and eggs on the weekly visit. Fish caught by the crew could also find itself on the mess table. The Lighthouse Service didn’t have regulations for what the crew would be fed, only that the cost of rations per member should not exceed a certain amount per day.

“Cook shown preparing a meal, USS Relief, St. George Base, Staten Island”, February 28, 1945.

Fresh water was stored in tanks in the lower decks that could hold 12,000 gallons and was supplemented with a filtration system to catch rainwater. Food was stored in a “bread room” and in a smaller pantry accessible through the room that housed the windlass, the mechanism that raises and lowers the ship’s anchors. Since lightships were reliant on supply ships, or “tenders,” that could be interrupted by emergency or bad weather, the Lighthouse Service required ships to carry 10 days worth of emergency provisions.

Her Appearance

As the name suggests, the main purpose of lightships was to provide a light (and other signals in daylight and low visibility) for aid in the navigation of other ships. Between lighthouses, lighted buoys, and lightships, it was the goal of the US Lighthouse Service to have vessels approaching the coast always have a light in view; however, these lights had to be distinct from one another so that navigators could identify which light they were seeing. Lights could be distinguished by their height above the waterline, their color, and how often they flashed.

“Light vessel 87 with its original rigging”, ca. 1909. U.S. Coast Guard Photo, South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Ambrose Lightship LV-87 was constructed from a set of specifications shared by five lightships ordered in 1906. These lightships were designed for oil lamps, where the light would be raised and lowered from the masts by the crew to refill the reservoir with fuel. LV-87 originally had spaces dedicated to storing and caring for these oil lamps. The masts were surrounded by wood “lantern houses” with roof hatches that could open, winches for raising the lights, and even a special landing pad made of metal springs to protect the light from breaking when lowered.

Technology was rapidly developing as LV-87 was being built. Though there is no mention in the original design documents and building contract, when Ambrose LV-87 was stationed in December 1908, she was fully electrified. She was converted from incandescent to arc lights several times during the period 1909–1922 but was incandescent thereafter with two 375mm lens lanterns of 15,000cp. Two generators were installed in case one failed, and she retained her oil lamps and associated equipment as a further back-up. The lantern deckhouses and other oil lamp spaces would be removed during LV-87’s 1932–1933 refit.

On the foredeck of LV-87 is a centuries-old piece of maritime technology: the ship’s bell. There are records of bells being used on ships dating back to the 15th century and they were used to mark the passage of time and the progression of the “watch,” or the crew’s shifts. Over time, bells were also used for safety and communication, allowing ships to talk to one another when visibility was low.

Lightships were always equipped with a bell to use as a fog signal (especially in the event of the fog horn malfunctioning), since their purpose was to mark their location for navigators at all times and in all weather.

Ambrose LV-87 still retains her original bronze bell that weighs around 1,000 pounds. It is inscribed “U.S.L.H.E. / 1907” for the US Light House Establishment who commissioned the ship and the year she was launched.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch

Ambrose LV-87 has specially designed cast-steel mushroom mooring anchors, weighing up to 7,500 pounds. Such high weight is used for mooring the ship to the bottom of the sea, and when the vessel is in severely exposed positions in deep water. This spherical mooring buoy is shackled into the submerged portion of the chain and carries a portion of the weight, forming a double catenary, which is of value in avoiding strains on the vessel as it surges in rough weather.

Mushroom anchors get their name from, as you might imagine, their rounded, mushroom shape. These are used extensively for moorings, and can weigh several thousand pounds for this use. Their shape works best in soft bottoms, where it can create a suction in sand or silt that can be difficult to break.

Though lightship Ambrose rarely left her station, the wheelhouse is the point from which the ship was navigated. The rounded front is fitted with extra-large bronze port lights (over the original steam radiator) for the navigator to look through. The wood ship’s wheel, original to the ship, uses a drum wound with the steering cable to manually turn the rudder by way of a pulley system running on deck. The wheelhouse needed to be able to communicate with both the windlass room and the engine room below decks and did so with a system of speaking tubes and bell pulls.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch

The wheelhouse underwent a few changes when Ambrose was converted from steam power to diesel power in the 1930s. The lamp houses (that had been designed for oil lamps before Ambrose was electrified) that surrounded the masts were removed, and a radio room and cabin were added to the rear of the wheelhouse.

Other Ambrose lightships and Ambrose Tower

Ambrose LV-87 was not the first or last lightship to mark the entrance to New York Harbor. Long before the construction of the Ambrose Channel, the first lightship of the Lower New York Bay (as well as the first open sea lightship in the US) was placed off Sandy Hook, New Jersey. After a brief period of suspension between 1829–1838, after the Navesink Twin Lights were constructed to mark the harbor entrance, the Sandy Hook lightship was reestablished, and served by several ships from 1823–1908. The station was renamed for the newly opened Ambrose Channel in 1908, with LV-87 serving as the first “Ambrose” lightship.

After LV-87 left the station a new ship took on the name “Ambrose.” Lightship Ambrose LV-111/WAL-533 was built in 1926 in Bath, Maine, with funds provided by Standard Oil after one of their barges struck and sank a different US lightship in 1919. LV-111 had several improvements over LV-87’s initial 1907 design, including a diesel engine and steel deck houses. LV-111 would mark the entrance to Ambrose Channel through World War II.

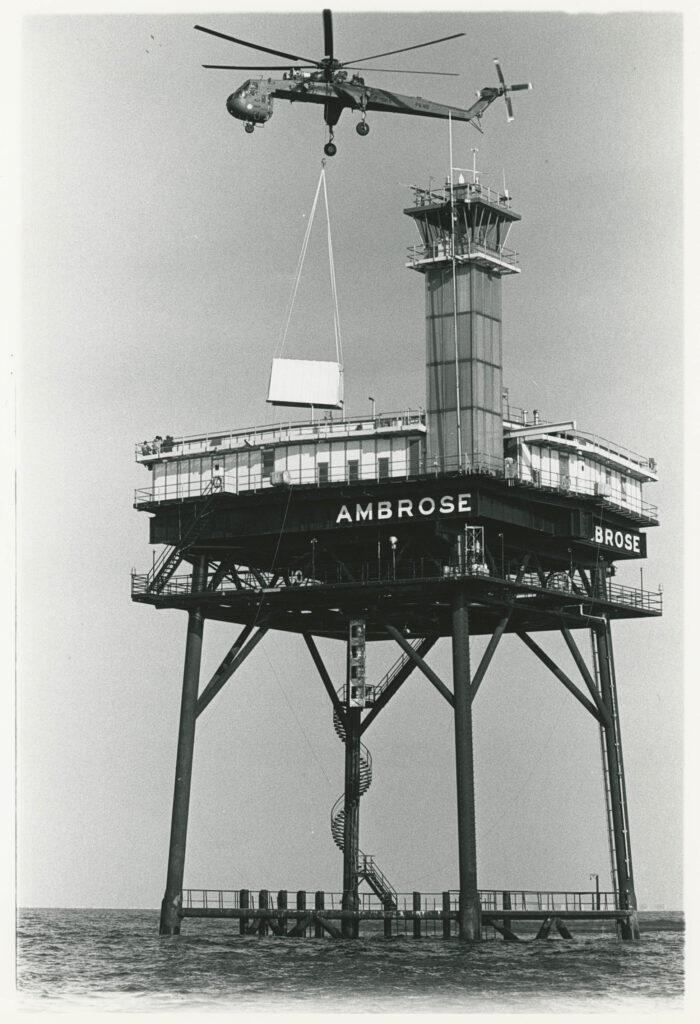

LV-111 was re-stationed and replaced by Ambrose WLV-613 in 1952. WLV-613 would serve as the last Ambrose Channel lightship. By 1964, the US Coast Guard was investigating how to replace the expensive-to-operate lightships of New York Harbor with a four-legged light platform. In 1967, Ambrose Lightship Station was replaced by the Ambrose Light Tower, ending the presence of lightships at the entrance to New York Harbor. The Tower would be replaced by a buoy in 2008.

[Helicopter dropping cargo at Ambrose Light], ca. 1981. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

The Restoration

With over $13 million in City capital funding secured from the Mayor’s Office, City Council, and the Manhattan Borough President, South Street Seaport Museum will undergo a major restoration of lightship Ambrose. This project will be multifaceted, and includes preserving historic elements like the wardroom, crew quarters, galley, and lamp; stabilizing the ship’s hull, bulkhead, and deck; and modernizing the lighting, safety systems, and HVAC. The Museum will not only restore Ambrose to what she looked like when she was stationed in New York Harbor as a working lightship, but will also ensure her longevity for generations to come.

Additional readings on lightships and lighthouses in the US

“A History of U.S. Lighthouses,” by Willard Flynt, 1993.

“Fleming, Candace. Women of the lights.” Morton Grove, IL, A. Whitman, 1996.

“Lighthouses of the world.” Compiled by the International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities. Old Saybrook, CT, Globe Pequot Press, 1998.

“Crompton, Samuel Willard. The ultimate book of lighthouses: history, legend, lore, design, technology, romance.” San Diego, CA, Thunder Bay Press, 2000.

“Jones, Ray. The lighthouse encyclopedia: the definitive reference.” 2nd ed. Guilford, Conn., Globe Pequot Press, 2013.

Lighthouses (National Park Service) – Lighthouses to visit listed by state and region

United States Lighthouse Society – The society is a non-profit historical and educational organization incorporated to educate, inform, and entertain those who are interested in America’s lighthouses, past and present, including an interesting list of fun facts.

National Lighthouse Museum – Located on the former site of the United States Lighthouse Service’s (USLHS) General Depot in St. George, Staten Island, the National Lighthouse Museum educates visitors about the history and technology of the nation’s lighthouses.