Pioneer, a simple coasting schooner, is a fine example of the utilitarian schooners that traded coastwise along the entire eastern seaboard of North America. Coasters carried timber, stone, grain, and dozens of other cargoes from port to port. Unlike Pioneer, nearly all were constructed of wood––with the largest having as many as six masts, stretching to more than 300 feet in length, and carrying thousands of tons of cargo. The small two-masters like Pioneer were ubiquitous, peppering the waterfronts and anchorages of Atlantic ports both large and small. Shallow draft and maneuverable schooner rigs allowed these vessels to maneuver and make passages, often with a tiny crew, frequently as few as three people.

Built in 1885, Pioneer originally carried sand and other heavy cargoes along the Delaware River for the Chester Rolling Mills, an iron and steel works in Chester, Pennsylvania. Unlike almost all American cargo sloops and schooners that were made of wood, Pioneer was built of riveted iron plates in Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, then American’s center for iron shipbuilding. She was the first of only two iron-hulled cargo sloops ever constructed in the United States, and is the sole remaining American merchant sailing vessel constructed of iron.

Pioneer was donated to the South Street Seaport Museum in 1970, and offered the first sailing programs at South Street. This concept fostered the idea of a marine school, which is still the foundation for the crucial role the vessel plays in the Museum’s K–12 educational programs and the Volunteer Sail Training Program. Through Pioneer sails, the Seaport Museum provides an exceptional experience to the public, catering to inquisitive students, seasoned New Yorkers, and eager visitors alike. By offering them the unique opportunity to venture out onto the water, this remarkable vessel grants guests a new vantage point to see the city allowing guests to forge a deeper connection with New York’s maritime past and present, illustrating exactly “Where New York Begins.”

19th Century Coastal Trading

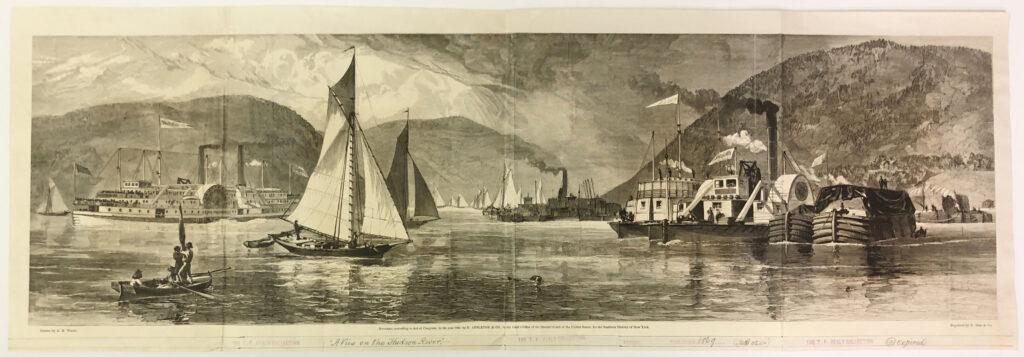

Before railroads and long-distance highways, Americans used the water for rapid and inexpensive travel between cities. Wind-powered sloops and schooners carried anything and everything that needed to be moved along the coast, from coal, stone, and ice to raw food, mail, and passengers.

Alfred R. Waud (American, 1828-1891); N. Orr & Co., engraver; Appletons’ Journal, publisher. “A View On The Hudson River”, 1869. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.078.0008

The schooner Pioneer is representative of the type of small coastal cargo vessels that were the delivery trucks of their era, carrying various cargoes between coastal communities. Thousands of similar cargo vessels helped knit America together from Colonial times into the 1930s.

Larger schooners, ranging from three to, in one case, seven masts, operated on the open sea in the coastal trades and sometimes foreign voyages. The handy little two-masters operated on bays and sounds, carrying, among other cargoes, lumber and stone from the islands of Maine, brick from the Hudson River, and oyster shells on the Chesapeake Bay.

Until the mid-19th century, much of the inshore cargo carrying was done by sloop-rigged vessels with tall single masts and large mainsails. The sloop rig went out of favor in the latter part of that century, primarily for economic reasons. The large single sail took more crew members to handle than the smaller sails of two-masted rig.

This model from the Seaport Museum’s collection depicts the Hudson River sloop Victorine, built in 1848 to carry paving stones from industrial sites along the Hudson River to New York City. During the Civil War she carried cannons from the West Point foundry to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“Hudson River sloop Victorine”, n.d. Wood, paint, thread. South Street Seaport Museum 1979.036

Today the only representative of the sloop-rigged cargo carrier is the historic 106′ Hudson River Sloop replica, Clearwater, built in 1969 to advocate for the Hudson River.

Pioneer herself was launched as a sloop at Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, in 1885, and re-rigged as a schooner 10 years later. She was originally built to carry sand mined near the mouth of the Delaware Bay on the river below Philadelphia, where it was used in the operation of an iron foundry.

Her Story

In December of 1885, Pioneer was enrolled for the first time with the United States government as a “vessel in domestic commerce.” Domestic ships in the United States are required to receive an enrollment certificate for fishing and coastwise trading, while international vessels need a certificate of registration.[1]From the adoption of the Constitution, the U.S. Federal Government has been vested with the exclusive power “[t]o regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States.” … Continue reading As a ship that moved cargo domestically, Pioneer had a certificate of enrollment as opposed to a certificate of registration.

Col. Walter R. Bruyere III (American, 1916-2004). “Pioneer”, ca. 1986. Wood, cloth, thread, metal, paint. Gift of Walter Bruyere 1986.022

Pioneer changed owners several times during her active career, being used at various times to transport local coal, lumber, brick, and oil.

In December of 1895, only ten years after her launch, she was sold to J.C. Fender of Philadelphia and was re-rigged as a schooner. In June of 1903, she was sold to J. Frank Black, who installed a gasoline engine, and six months later she was re-rigged again, but this time as a sloop. In July of 1907, her masts were removed and she operated as a power boat.

By 1930, when new owners moved her operation from the Delaware River to Massachusetts, she had been fitted with a full-powered diesel engine, and was no longer using sails for propulsion.

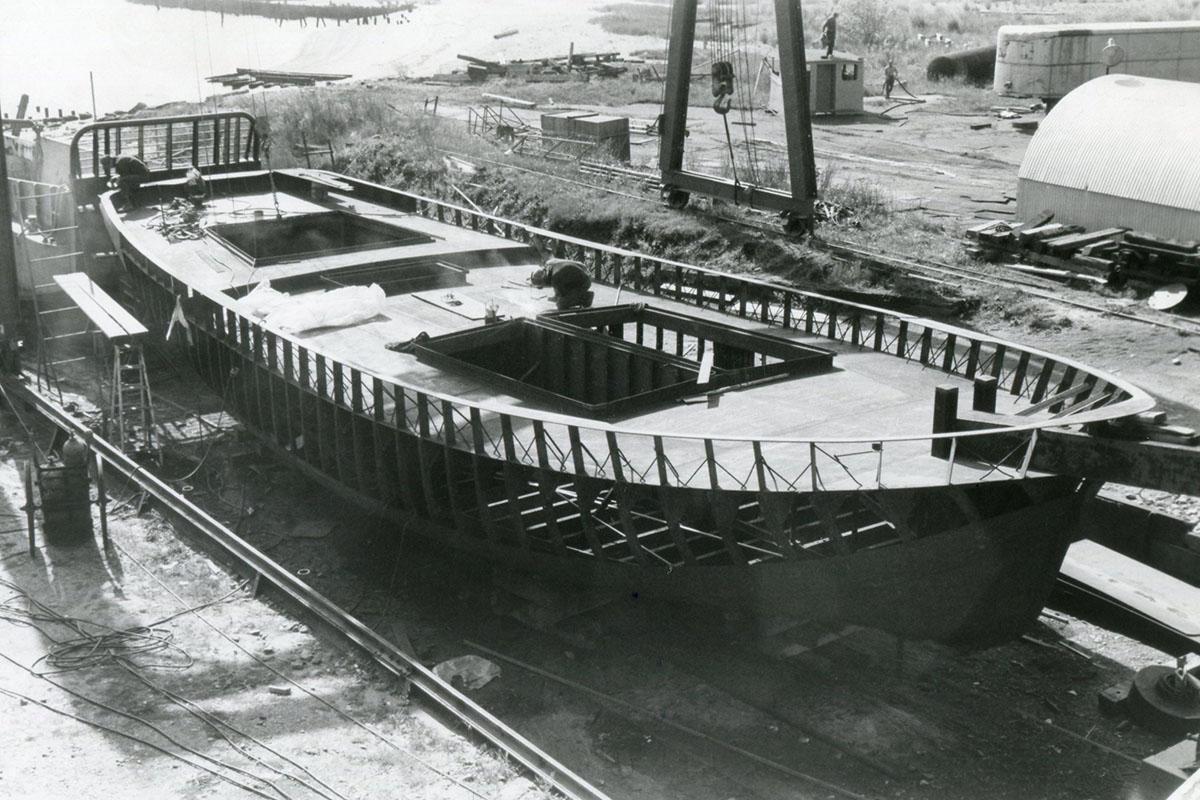

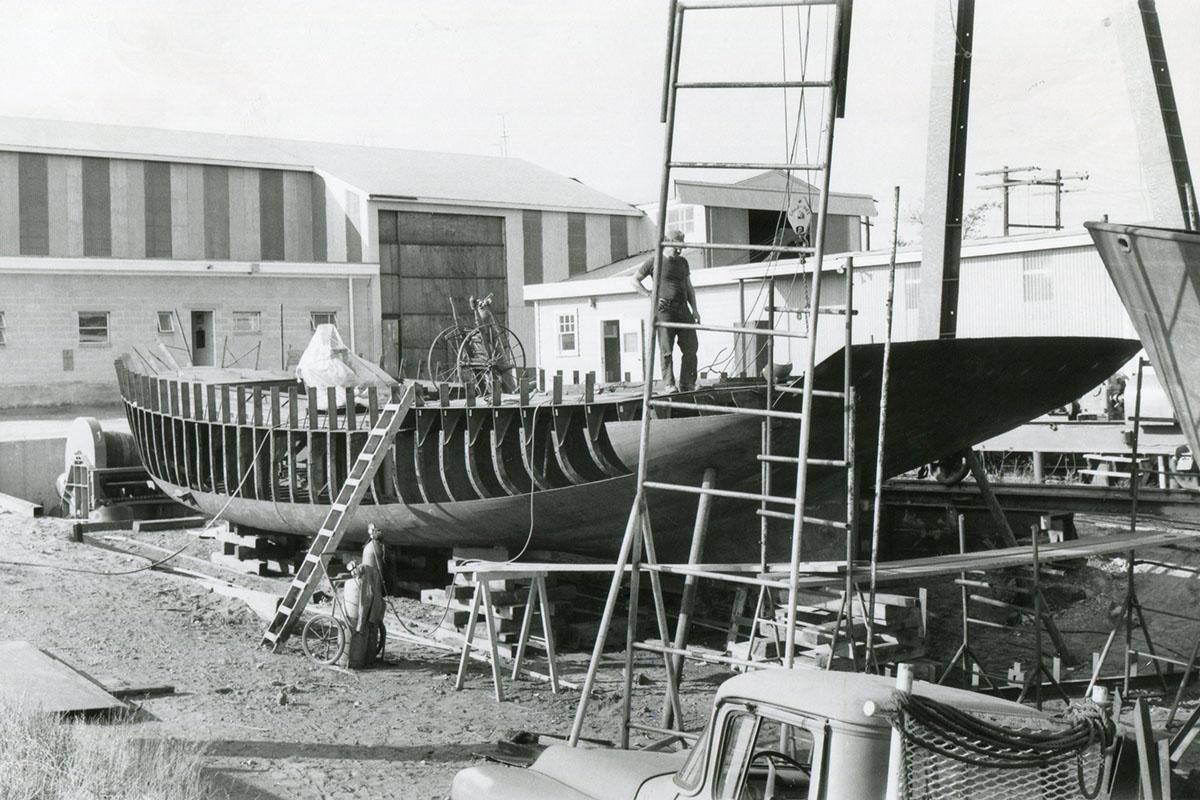

In 1956 Pioneer was bought by Dan. W. Clark of New Bedford, Massachusetts, but was later beached as unserviceable. This would have been the end for most vessels. However, in 1966, Russell Grinnell, Jr. of Gloucester, Massachusetts, decided to rescue the vessel, rebuilt her hull with steel plating, gave her back the traditional schooner rig, and found uses for her in his dock building business.

[Views of the hull of schooner Pioneer in shipyard during restoration], 1966-1968. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Grinnell oversaw the rebuild of Pioneer between 1969 and 1970 at the Gladding-Hearn shipyard of Somerset, Massachusetts. Tragically, in April of 1970, he passed away in an accident. That same summer, Pioneer was donated to the South Street Seaport Museum, becoming the third vessel addition of the year. Prior to Pioneer arriving August 30th, the Museum acquired the steam-tug Mathilda, and the cargo ship Wavertree, which arrived on July 30th and August 11th respectively.

Pioneer Marine School

The summer after Pioneer arrived at the Seaport Museum, volunteer Dick Rath––who was also editor of Boating magazine––organized a sailing program for youth enrolled in drug rehabilitation programs; this was the first sail training program on a Museum vessel. An outgrowth of this Summer was the awareness that the successful rehabilitation of former drug abusers could happen at sea, and it was out of this concept that the idea of a marine school was developed.

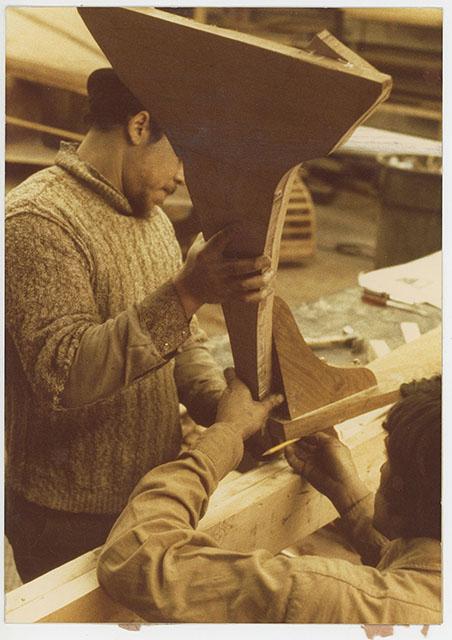

The Pioneer Marine School existed primarily for the purpose of providing an opportunity for people who were unemployed to develop skills and a good employment history so that they would be able to find work.

Based aboard the old ferryboat Maj. General William H. Hart, docked at Pier 15, the school included classroom presentations and lectures, as well as hands-on workshops and apprenticeships in seamanship, engine theory, carpentry, boat repair, welding, electricity, and first aid.

“Pioneer Marine School patch”, ca. 1970s. Cloth, thread. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

The Marine School would later work with the Wildcat Service Corporation and receive funding from the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which broadened the School’s student recruitment efforts. The School would continue until 1980, when a loss of city funding led to permanent closure.

Left: [Member of the Pioneer Marine School working on a machine part], ca. 1970s. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Right: [Two members of the Pioneer Marine School woodworking], ca. 1970s. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Since her first day at the Museum, Pioneer’s mission has been “to introduce city kids to the wide horizon of the sea, and to carry the Seaport Museum story to each port at which she called.” –South Street Reporter, Fall 1971.

Pioneer is dedicated to re-creating the 19th century sailing experience for the general public. Today, her education and sailing programs are healthier than ever. She carries people of all ages on public sails of New York Harbor, and sails with school groups and classes throughout the week as part of our robust educational programming.

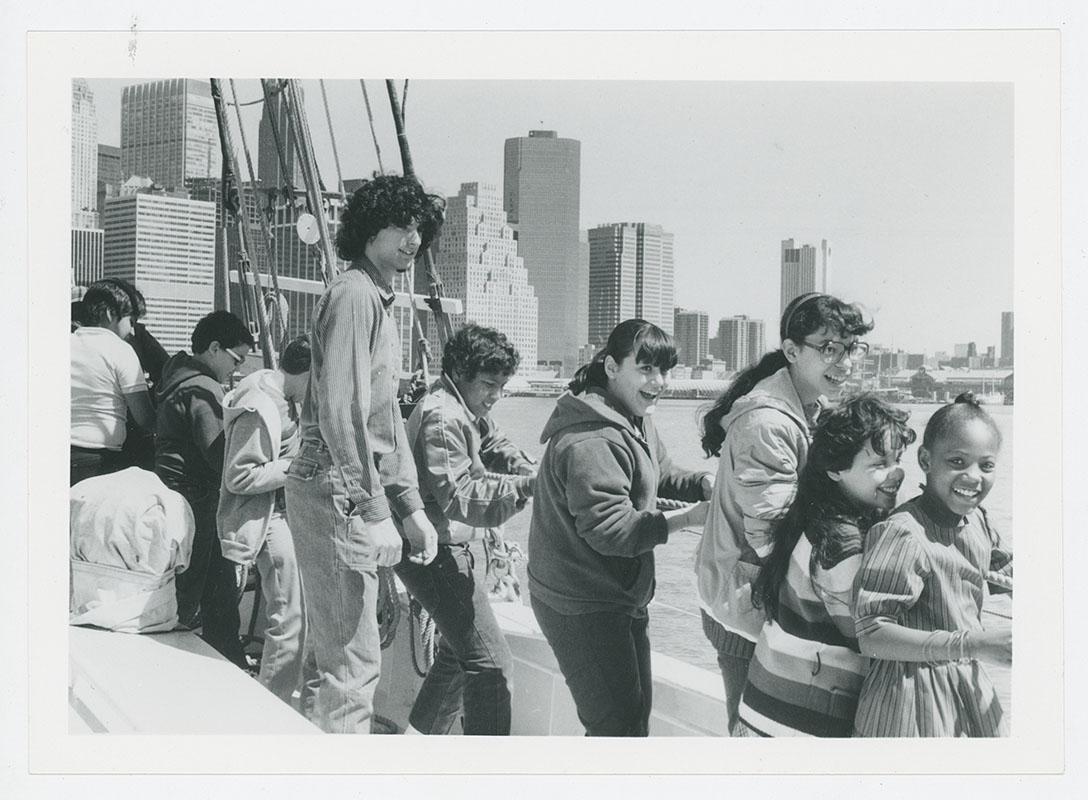

Left: [Young adults and children smiling while hauling on rope on board schooner Pioneer], ca. 1980s. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Right: Photo credit Richard Bowditch.

Last, but not least, Pioneer has been and continues to be, one of the Museum’s main platforms for volunteering and promoting tall ship sail training. Generations of sailors, seamen, and captains grew out of the volunteer Sail Training Program of the Museum. Today, from April to October, the schooner sails with professional and volunteer crew members during weekdays, weeknights, and weekends.

The Museum’s Sail Training Program teaches people, of all skill levels, how to crew aboard this historic ship. It’s a one of a kind opportunity to experience New York Harbor from a completely different perspective, while learning traditional maritime skills.

Additional reading and resources on schooners and coastal trading

“The Schooner” by David R MacGregor, 1997. This book covers over 400 years (from 1600 to the 1990s) of schooner development with many photographs and much technical information on schooners in North America and Europe.

“The American Fishing Schooners 1825–1935” by Howard Chapell, 1973. This book chronicles the development of the classic American East Coast Grand Banks and inshore fishing schooners, including line drawings and sail plans.

“Blue Water Coaster” by Francis Bowker, 1972. A first-hand account of life aboard one of the big coasting schooners of the Eastern seaboard of the United States.

“The Quest of the Schooner Argus” by Alan Villiers, 1951. A first-hand account from Villiers’ 1950 sailing with the Portuguese fishing fleet to fish on the Grand Banks and Davis Straits.

“Sloops of the Hudson” by William Verplanck and Moses Collyer, 1908. An Historical Sketch of the Packet and Market Sloops of the Last Century, with a Record of Their Names; Together with Personal Reminiscences of Certain of the Notable North River Sailing Masters.

References

| ↑1 | From the adoption of the Constitution, the U.S. Federal Government has been vested with the exclusive power “[t]o regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States.” Vessel documents facilitated taxation and protection of domestic shipbuilding and trade by tracking the origin and intended operation of ships.; From “U.S. Maritime and Shipbuilding Industries: Strategies to Improve Regulation, Economic Opportunities, and Competitiveness.” House Hearing, 116 Congress, March 6, 2019. |

|---|