Enhancing Accessibility Through Collections Digitization

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections, and Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

February 25, 2021

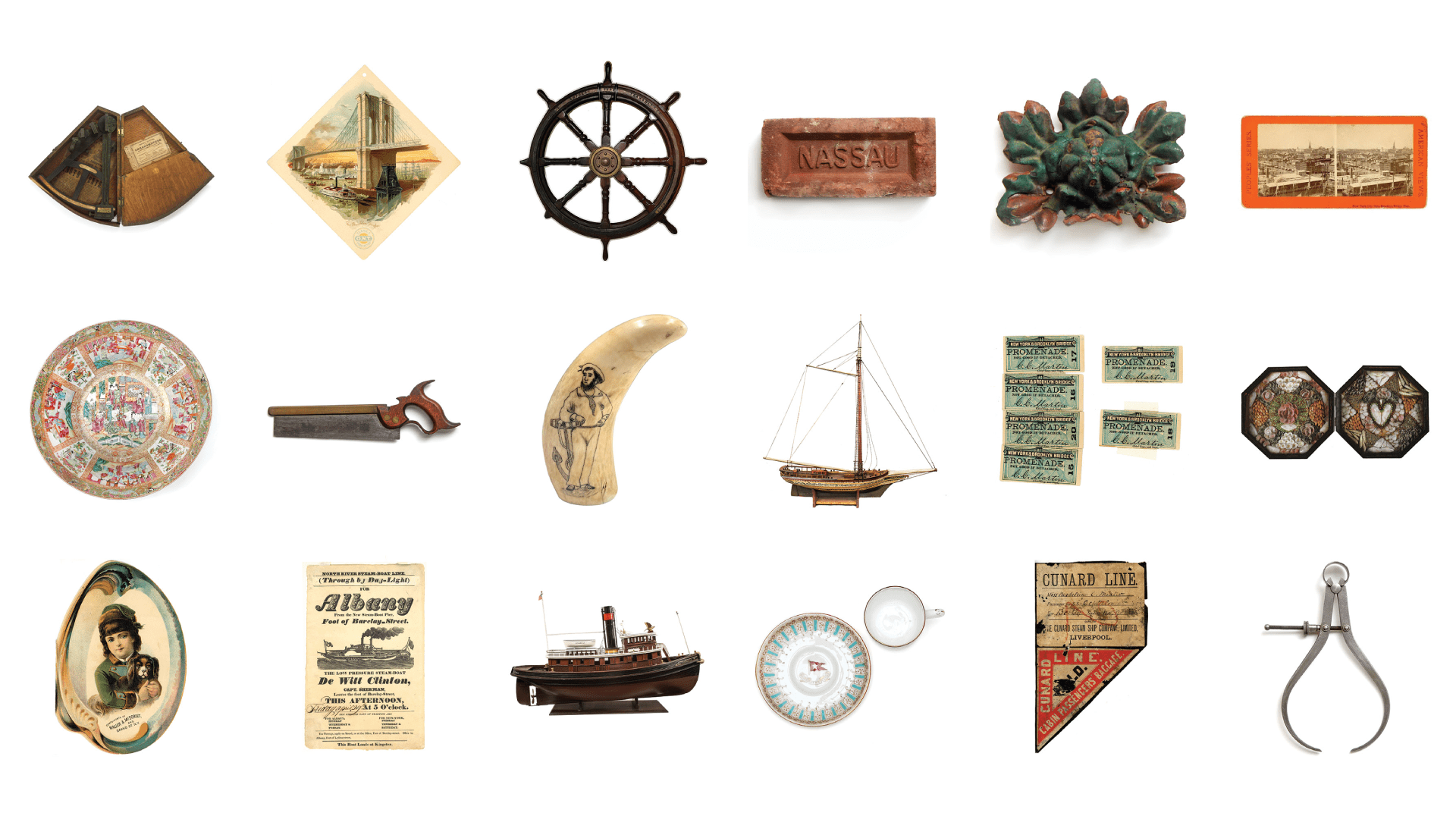

The South Street Seaport Museum is thrilled to be joining the many museums and cultural institutions that make their collections available online for visitors to browse, research, and enjoy. As the two staff members of the Collections Department, we’ve been hustling during the past months getting ready to launch the Museum’s Collections Online Portal; however, thinking back on the inventories, digitizations, and the diverse collection care and research projects we’ve done since 2015 (when we both joined the Museum), you could say we’ve been working towards a public collections portal for years.

This first iteration includes database entries for over 1,300 works of art and artifacts covering a variety of mediums, historical subjects, and themes relating to the growth of New York City as a world port. This public portal also represents many facets of what it means to care for historic collections, as well as the passion of many staff members, interns, and volunteers who contributed to it over the past few years.

The importance of collection inventory

Any type of collection online database depends on reliable data. When someone enters a query into a search box, they often assume the results are accurate. It’s up to those of us, tasked with managing collection information, to make sure that’s true.

Inventory is at the heart of all collections work. In order to make sure that the object’s catalog record has factual data, the first thing we do is examine the object itself. Nearly all artworks in the collection have paper records dating back to the time they were first acquired, along with their exhibition history, loans history, and object entries in the database. However, solely relying on previous records for object data can be like playing a game of telephone. The surest way to check if the physical description of an object (which includes its dimensions, medium, inscriptions and subjects depicted) is correctly included in the database is to double-check the artifact.

Inventory projects are deliberate examinations of a series of related collections items. These projects also include adding supplementary information to the object entries with outside research; it’s an essential thing to record the physical characterics of a silver teapot, but recording that the teapot was used by 19th century passengers of the Guion Line adds the object’s historical significance. At the Seaport Museum, some of our most exciting and significant recent inventory projects have been done by our Collections Management, Curatorial, and Archives Interns.

Above left: Summer 2017 Collections Care Intern Josie C. condition reporting ship models.

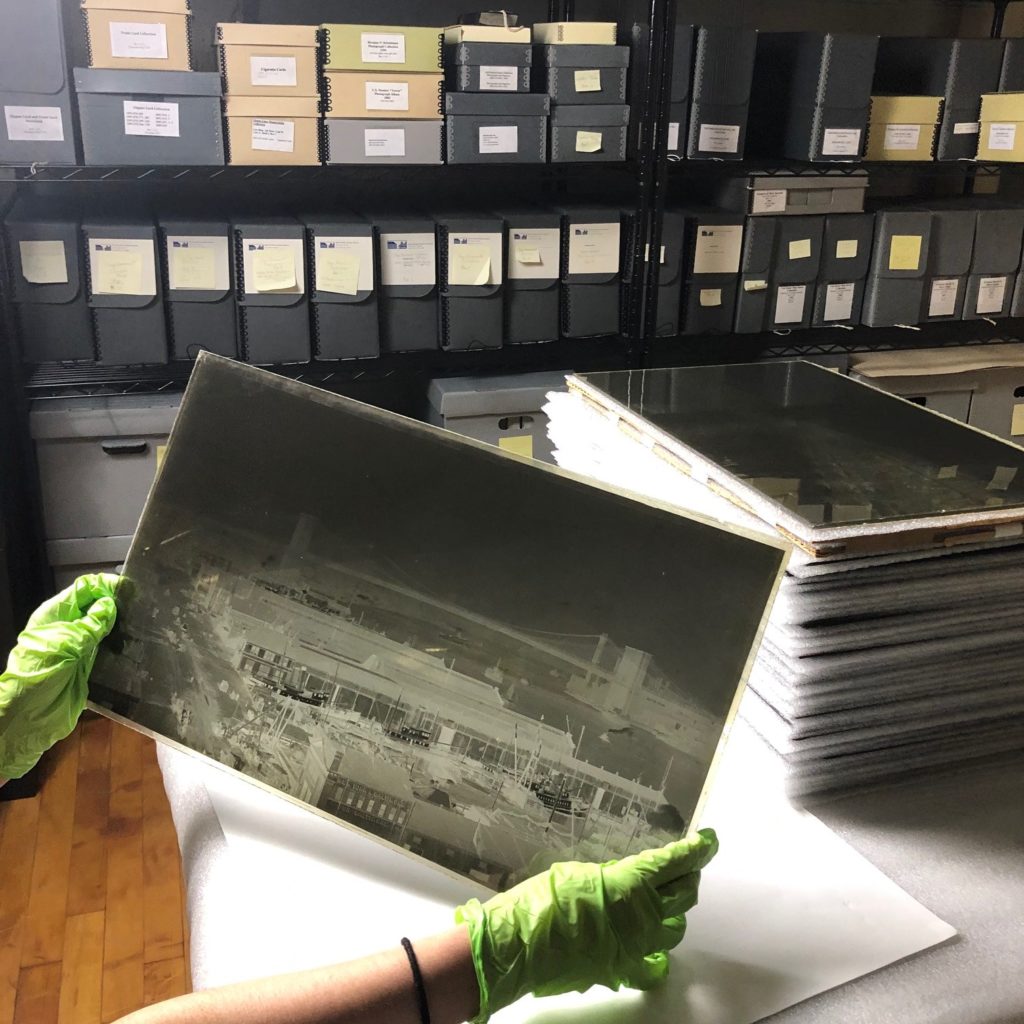

Above center: Summer 2019 Collections Care Intern Lani W. inspecting glass plate negatives.

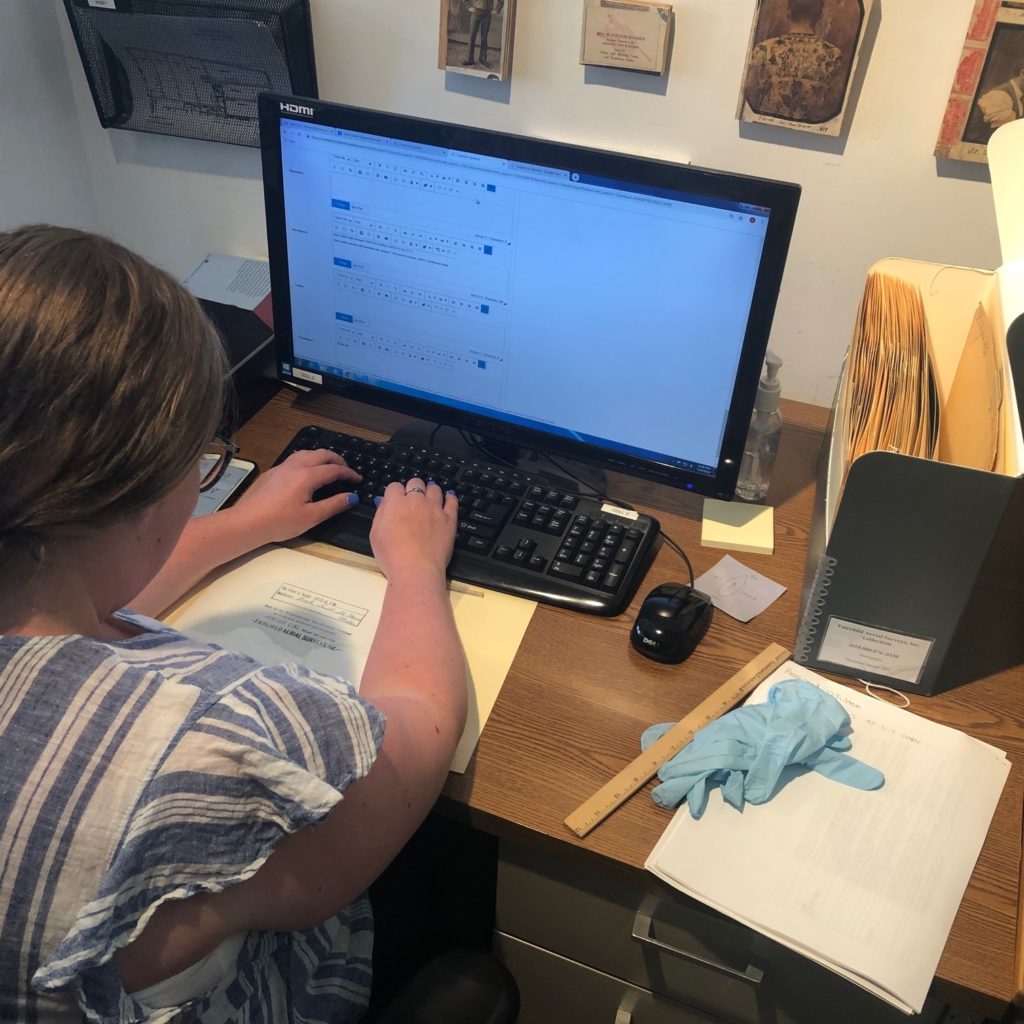

Above right: Winter/Spring 2019 Archives Intern Kasey D. cataloging and describing photographs.

Of the eight galleries of objects included with the launch of the online portal, all but one includes hours of inventory and cataloging work done by our dedicated interns. From filling out entries for 449 19th century clipper cards, to digitizing the World War II silhouettes of sailors, to processing the recent acquisition of almost 300 black and white mid-20th century aerial photographs of New Harbor, to researching the New York landmarks depicted in illustrations from D.T. Valentine’s Manual of the Corporation for the City of New York, this work brought our database entries to a level of depth and accuracy that we’re happy to share with digital visitors.

Along with the time and thoughtfulness required for good catalog work, developing and reviewing our inventory guidelines has been crucial to creating consistent database entries. Our inventory guidelines follow The Getty Research Institute’s Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA), a set of guidelines for best practice in cataloging and describing works of art, architecture, other material culture, groups and collections of works, and related images. On top of the CDWA conceptual framework we’ve created additional guidelines for the topical points (in the “subjects” field in our database) that capture contextual information in a way that can be searched via keyword.

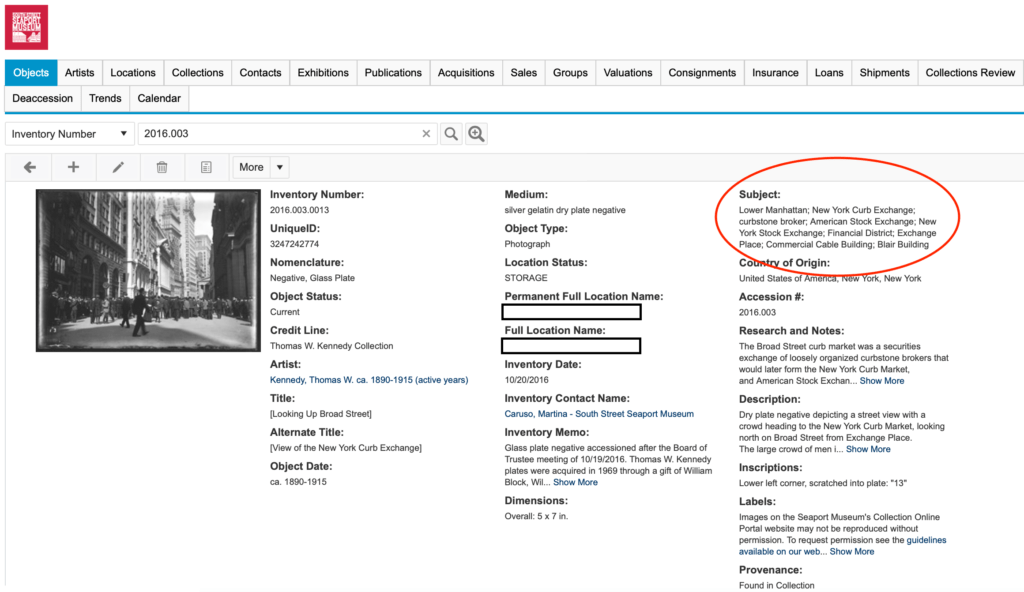

Topical points that are essential to the visitor of any online database. A visitor to the Seaport Museum’s Collection Online Portal will be able to search various terms, including broad keywords like street scene, green space, and skyline, as well as more specific ones like White Star Line, Lower Manhattan, and World War II, in the “subjects” section of the portal.

Such subjects are standardized based on The Getty Research Institute’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), and based on our own knowledge of the collection, which drives our collection database guidelines for the updates and cleaning of data that staff and interns perform on a daily basis.

Every time we review these guidelines we determine how to narrow them down, while at the same build a richer database of keywords and subjects. Recently we discussed what terms will our website visitors be most interested in searching, and how do you account for variations of a term. We had a long discussion about every subject in a clipper ship card, and if all of them need to be described.

Museum Industry

Further investigation for the project includes learning about how other institutions have increased access to their collections. Notable examples include the online collection database of The New York Public Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Frick Collection, The Rubin Art Museum, and SFMOMA.

The online databases of the above institutions have gone far beyond the first computer collections databases that were developed for museums. A collection management database is a software system designed to catalogue and manage collection items, plan and manage exhibitions and loans, organize conservation documentation, and manage digital assets. These databases were first developed for the specialist working inside the museum—the curator, the registrar, the collections manager, and the conservator. These management systems were not designed to be explored by a wide range of publics with unique motivations to search and browse. As the internet became more accessible, museums began developing a presence online and the idea of sharing the once “behind-the-scenes” database took off. Of course, adapting a specialist’s tool to an accessible offering requires careful consideration about what the digital visitor could want and need.

Along with the addition of keywords discussed above, attention to user experience can be established in dozens of ways in museum collections portals. Integrating the portal into the larger museum website for straightforward navigation, prioritizing high quality images of artifacts to attract visual learners, and having flexible search options are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what can be done to make collections databases user-friendly. The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s “Browse Artworks by Color” feature is a great example of how a database can go above and beyond as a point of entry into the museum’s collection.

Though there is no lack of inspiration to take from other museum’s online collection portals, the majority of art museums in the United States don’t have any portion of their collection databases available online[1] “Art museum collections online: Extending their reach” by Joan Beaudoin. MW20 Online. March 31-April 4, 2020.. Collections portals enrich the amount of historical artifacts and artworks accessible to all with an internet connection; however, even the basics of “cleaning up” collections data for public use, adding high quality images, and improving searchability requires a lot of dedicated resources and staff time. Whether or not an institution is able to share an online collection portal also depends on the capabilities of the museum’s collections management software and other technology infrastructure. At the Seaport Museum, launching the portal had a lot to do with the features included in our current system.

Tools and Technologies

The Seaport Museum’s internal collection management database, Collector Systems, contains nearly all digital records of the Museum’s permanent and working collections of over 28,500 items, along with thousands of associated records of artists, museum publications, exhibitions and loans history. You can imagine how collections care can be greatly enhanced by a strong database and good collections management policies around its use.

One way in which Collector Systems was particularly useful during the preparation for the public portal was its ability to create “groups” of objects. Object groups make it easy to break up thousands of records into more manageable sections, to clean up, research, and refine data. Such groups are the basis of 50% of our ongoing collection inventory, as we often create and assign groups of objects to be researched and cleaned to our graduate interns. The other 50% of collections is usually catalogued and condition reported by location, down to cabinet unit and shelf number. The eight galleries we’ve made publicly available began as groups on our back-end.

Above: a screenshot from the Museum’s collection management database showing one database entry, highlighting the subject field.

Another key feature of Collector Systems that allowed us to launch the collections portal was the ability to directly publish the digital assets and data from the database. Some collection databases require separate software to manage a public portal. With Collector Systems, the content you can browse is a version of the same database entries we use on a daily basis, excluding internal-only data fields (such as exact location for security purposes.) When digital visitors search our collection using titles, dates, and subjects’ keywords, they are essentially running searches like we do on the back-end of the database during our work.

What’s Next

This project is ongoing. As the collections items highlighted online will grow in number we can’t wait to both document and share more artifacts, and learn how digital visitors utilize the portal. Assessing popular searches and receiving feedback from visitors and internal staff will be a key aspect of the next stages of the portal implementation.

Our ongoing implementation of museum documentation will add in the main goal of review and revision of the language used in our catalog. Like other many museums, libraries, and archives we are engaged in the review of collection description practices to create more equitable, inclusive, and diverse collection’s descriptions for our users, following the guidelines of the American Alliance of Museums Code of Ethics, the Society of American Archivists Code of Ethics, and the CIDOC – ICOM’s International Committee for Documentation.

We are accelerating research into collection items related to underrepresented cultures, groups, and individuals. And as some collection items held by the South Street Seaport Museum may include insensitive wording and overt expressions of bigotry or bias, as well as outdated cultural or geographical references and stereotypes, our goal is to improve access to these works by enhancing their descriptions in a sensitive, respectful, and accurate manner.

Stay tuned for more, as we’ll share the next steps of this new chapter of the Seaport Museum’s digital offerings, as well as our critical and ethical cataloging work.

Additional readings

Bringing a Collections Catalogue to Life, by Elizabeth Merritt, Center for the Future of Museums, American Alliance of Museums, July 31, 2014.

Digital Is More Than a Department, It Is a Collective Responsibility, by Loic Tallon, Chief Digital Officer, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 24, 2017.

Report urges massive digitization of museum collections, by Elizabeth Pennisi, American Association for the Advancement of Science, April 4, 2019.

Museopunks Episode 41: Digitization is not neutral, by Suse Anderson and Ed Rodley, American Alliance for Museum, December 19, 2019.

What Does a Welcoming Online Collections Portal Look Like?, by Cassi Tucker, American Alliance of Museums, April 20, 2020.

The Rijksmuseum Had Its Lowest Attendance Last Year Since 1964. But Its Digital Audience Has Grown by Leaps and Bounds, by Sarah Cascone, Artnet, January 13, 2021.

About the Collections

The collections and archives of the South Street Seaport Museum document the rise of New York as a port city, and its role in the development of the economy and business of the United States through social and architectural landscapes with over 28,000 works of art and historical artifacts, and over 80,000 archival materials.

References

| ↑1 | “Art museum collections online: Extending their reach” by Joan Beaudoin. MW20 Online. March 31-April 4, 2020. |

|---|