History, provenance, and care for collection artifacts displayed outdoors on Water Street

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

January 28, 2021

The South Street Seaport Museum owns two large mid-19th century anchors, prominently displayed on Little Water Street, in front of the Museum’s Bowne & Co., Stationers.

It’s not unusual to see artifacts like these on lawns or other outdoor public spaces. Many maritime museums, lighthouses, or historic houses close to the water proudly show large objects like these, either as romantic nautical motif decorations, or as historical markers. In other permanent displays, anchors are used as memorials to those who lost their lives when their ship sank, or as monuments to Navy heroes.

The anchors at the Seaport Museum have two distinct, fascinating histories, but before I tell you the stories of their provenance, let me briefly explain to you the history of Admiralty Pattern anchors and of anchors in general.

A brief history of anchors

It is known that anchors were created shortly after the invention of boats, and that at first, an anchor was simply a stone on the end of a rope, heavy enough to sink to the bottom of the sea.

The oldest known ships with anchors were built in Egypt between 5000 and 6000 BCE. We know this thanks to pottery vases, discovered in tombs of the same period of time, on which crude representations of large ships were painted. These drawings show “58 oars, or more probably paddles, on each side, and two large cabins amidships, connected by a flying bridge, and with spaces fenced off from the body of the vessel. The steering was, apparently, affected by means of three large paddles on each side, and from the prow of one of the boats hangs a weight, which was probably intended for an anchor.”[1] Ancient and Modern Ships, Part I, Wooden Sailing-Ships, by Sir George C. V. Holmes. Victoria and Albert Museum Science Handbooks.

By 800 BCE bronze anchors were being produced in Malta, and by about 300 BCE anchors were made of iron, with a more modern appearance.

In 1929 a 16-foot long anchor from a ship of the Roman Emperor Caligula – dating from about 40 CE – was one of several salvaged. [2] Nemi Ships: How Caligula’s Floating Pleasure Palaces Were Found and Lost Again, by Paul Cooper, published on Discover Magazine on November 7, 2018. The excavated ships were built during the transition between wooden and iron anchors, and they were the first Romans ships found with intact large Admiralty design anchors.

A photograph from 1930 of one of the two Roman ships recovered from Lake Nemi. The New York Times, October 19, 2017.

Anchors for the following 1900 years were predominantly in the same general shape as the Nemi ships’ anchors: two symmetrical arms to dig into the sea floor, a stock at right angles to the arms, and a long shank connecting the arms to the stock. This type of anchor is called an Admiralty Pattern anchor, or simply “Admiralty,” or “Fisherman.” This basic design remained unchanged for centuries, with the most significant changes being to the overall proportions, and a move from stocks made of wood to iron stocks in the late 1830s and early 1840s.

The East River Anchor

This anchor was pulled up from the bottom of the East River, near 33rd St., in November 1974, during some general waterfront operations by Steers Inc., a renowned New York-based contracting company focusing on heavy maritime infrastructure work, including bridge and pier construction, tunnel, foundation, and sewer and drain work, between 1929 and 1987.

Their description of the discovery seems pretty emphatic and dramatic, as described in an article in Museum’s publication “South Street Reporter” one year later, in the fall of 1975 issue:

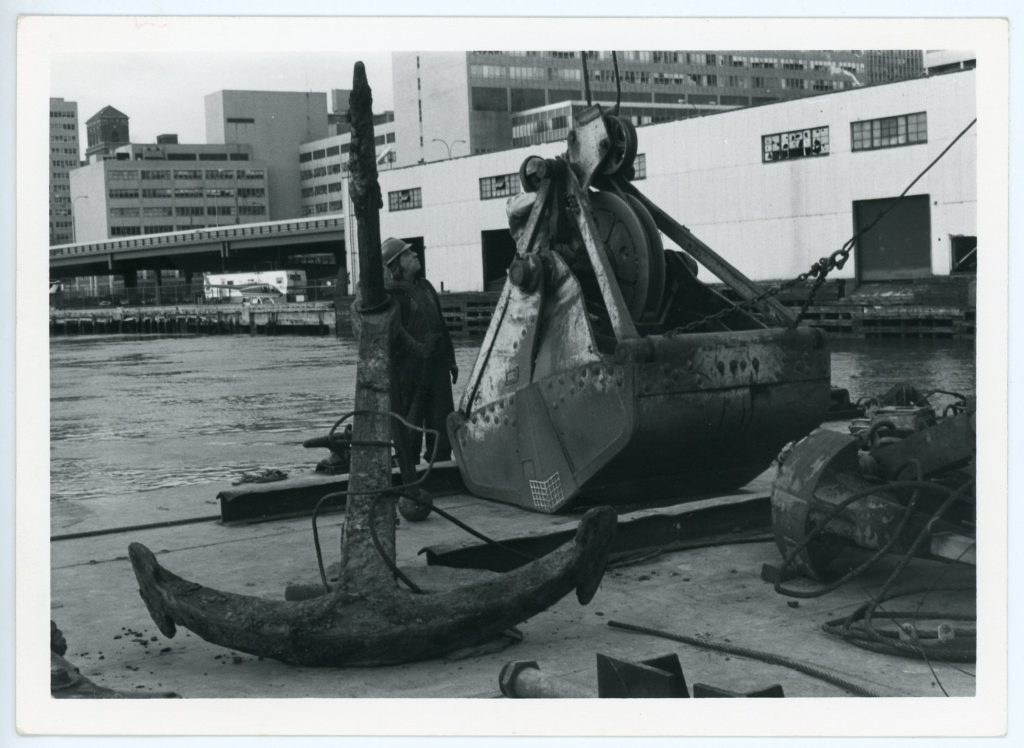

Admiralty Anchor, ca. 1850. Iron. Gift of J. Rich Steers, Inc., South Street Seaport Museum 1974.061

“One grey icy-cold day last November, derrick Steers No. 2 was digging a trench in the East River near 33rd Street. At ten o’clock in the morning we were bringing Sterling to the rig to deliver our cargo of fuel oil. Steer No. 2 was working away biting huge chunks of mud and rocks out of the river bottom. As Sterling drew near the rig No. 2’s huge two-ton bucket caught on some large object lying on the river bottom. The engineer took such a strain in the bucket’s cable that the whole rig went down to the head. For a moment the gargantuan tugging match appeared to be a draw. Then all in one burst the bucket freed itself, the derrick rocketed violently, and the engineer eased up on the cables and waited for the rig to calm itself. Slowly he remitted lifting – and there, above the surface of the harbor for the first time in probably a hundred years, was a magnificent, ten foot tall, 5000-pound, sailing ship’s anchor.”

Left: J. Rich Steers, Inc., pulled out a ca. 1850 iron anchor from the East River. South Street Seaport Museum Archives H14-0043

Right: J. Rich Steers, Inc., pulled out a ca. 1850 iron anchor from the East River. South Street Seaport Museum Archives H14-0045

J. Rich Steers, Inc. generously gave the “prize” to the Museum, who first placed it on Pier 16, beside the gangway of the 1935 floating hospital Robert Fulton[3]Robert Fulton was one of New York Port’s most noble floating hospital. Launched in 1935 at J. Mathis Shipyard in Camden, New Jersey, she was the fourth of similar ships built by the St. … Continue reading, and later moved it in front of the wood-working and ship model-working container on Pier 15.

The 63rd Street Tunnel Anchor

This anchor was one of three old ships anchors found in 1971 in the East River, and brought to the surface by men excavating for the 63rd Street railroad and subway double-decked tunnel, connecting Manhattan to Queens.

The tunnel passes under the East River and Roosevelt Island, with four tracks in two tunnels; the top level would be used by the IND 63rd Street subway line (today’s F and Q) and the bottom for the new LIRR East Midtown connection

Admiralty Anchor, ca. 1880-1910. Iron. Gift of the Metropolitan Transit Authority, South Street Seaport Museum 1979.093

Construction of the 63rd Street Tunnel began in 1969. The first of the tunnel segments was lowered into place at the end of August 1971.[4] First Section of 63d St. Tunnel Lowered to Bottom of East River, by Frank J. Prial, published on The New York Times on August 30, 1971.

Completion of the tunnel and its connections was delayed by the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis, and by 1980 it was reported that the lower level tracks in the tunnel would never see an LIRR train. The New York Times referred to the lower side of the tunnel as a “dead-end to nowhere.”[5]Tunnel Project, Five Years Old, Won’t Be Used; Ravitch Orders Inquiry Tunnel Project, Five Years Old, To Go Unused Two-Deck System Planned Stairs Would Be Sealed, by David A. Andelman, … Continue reading The upper level was not opened until 1989, twenty years after construction started.

Opportunities in taking care of collection artifacts in public spaces

Museums that are organized as a campus, including historic buildings, historic signage, and artifacts in public spaces, face several opportunities in taking care of these items. Usually, the general day-to-day monitoring and preservation is shared between different staff members, with different areas of expertise, under the overall supervision of the Collections Department, which provides general oversight, conducts yearly reports, performs condition assessments, or commissions conservation treatments.

While buildings and historic signage provide a fair amount of challenges, and require active collaboration between various departments and external agencies, objects placed in the neighborhood – like statues, anchors, or other types of art installations – are slightly easier to handle. Artifacts in public spaces are usually known to be objects from the collection, accessioned, and placed under the direct care of the Museum, following collection management policy, preservation procedures, and within purview of staff members.

Another key aspect of documenting and preserving collections placed outdoors is addressing the weather of the institution’s region, as well as preparing a risk assessment of its climate. In recent years, we have lived through an increase in changes of high and low temperatures, humidity, high winds, and high rainfall, and the expectation, as stated in a recent interactive piece by the New York Times, is that we should be prepared for more hurricanes and extreme rainfalls in the prospective future.

Our two anchors are accessioned artifacts from the Museum’s collection, documented at the time of possession in 1974 and 1979, that have been placed on view, outdoors, for decades, since their first day on-site.

Anchors on Pier 15 under the snow, ca. 1990. Sal Polisi Photo Archive, South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

The anchors were initially on display on the Museum’s Piers 16 and 15, close to the East River and the ships docked there. Due to the proximity to the waterfront operations at the docks, there were increased opportunities for water damage, floods, accidents and incidents.

In the years prior to my arrival to the Museum in the summer of 2015, the anchors had been moved to a more protected and safe location on Water Street, and they are now being documented on a regular basis. We implemented a monitoring system involving the staff working at Bowne & Co., visitor services staff, and facilities and housekeeping staff, so incidents, improper interactions (such as climbing), and general appearance are closely watched. Each time the anchors are moved now with the help of our terrific waterfront staff, and their movement is documented so that collaboration, tools, training, and collection care culture could be shared and further implemented within staff, for generations to come.

Above left: Detail of Admiralty Anchor, ca. 1850. Iron. Gift of J. Rich Steers, Inc., South Street Seaport Museum 1974.061

Above center: An Admiralty Anchor, ca. 1880-1910, being moved with the assistance of Museum’s waterfront staff, October 2020.

Above right: Detail of Admiralty Anchor, ca. 1880-1910. Iron. Gift of the Metropolitan Transit Authority, South Street Seaport Museum 1979.093

There is still more to be done with these anchors, including installing additional informational signage nearby, so that visitors can read about the anchors’ fascinating provenance and understand their part in the Museum’s mission, history, and vision, as we continue to preserve, research, and interpret maritime cultural heritage, and tell the history of Where New York Begins.

Sources and additional readings

Ancient anchors–technology and classification, by Gerhard Kapitän, published in The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration, 1984.

Ancient and Modern Ships, Part I, Wooden Sailing-Ships, by Sir George C. V. Holmes. Victoria and Albert Museum Science Handbooks.

The Nemi Ships, University of Chicago.

Roman wrecks of Lake Nemi, by Cormac F. Lowth. National Maritime Museum of Ireland.

Managing Risks: What are the agents of deterioration? by Rebecca de But, the Library of Trinity College Dublin, for Google Arts & Culture.

Conservation of Public Art, by Rika Smith McNally and Lilloan Hsu, for the Getty Conservation Institute.

References

| ↑1 | Ancient and Modern Ships, Part I, Wooden Sailing-Ships, by Sir George C. V. Holmes. Victoria and Albert Museum Science Handbooks. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Nemi Ships: How Caligula’s Floating Pleasure Palaces Were Found and Lost Again, by Paul Cooper, published on Discover Magazine on November 7, 2018. |

| ↑3 | Robert Fulton was one of New York Port’s most noble floating hospital. Launched in 1935 at J. Mathis Shipyard in Camden, New Jersey, she was the fourth of similar ships built by the St. John’s Guild. The sole purpose of this vessel has been to take out senior citizens and children for a boatride in New York Harbor, June through Labor Day, and assist the passengers with physical and mental health. She was brought to the Seaport Museum on September 20, 1973, to be used for museums functions, including a floating auditorium for seminars and sea chanteys, gala banquets, small lancheon parties, and community meetings. |

| ↑4 | First Section of 63d St. Tunnel Lowered to Bottom of East River, by Frank J. Prial, published on The New York Times on August 30, 1971. |

| ↑5 | Tunnel Project, Five Years Old, Won’t Be Used; Ravitch Orders Inquiry Tunnel Project, Five Years Old, To Go Unused Two-Deck System Planned Stairs Would Be Sealed, by David A. Andelman, published on The New York Times on October 11, 1980. |