The research process for the Captain Frank Ley Collection

A Collections Chronicles Blog

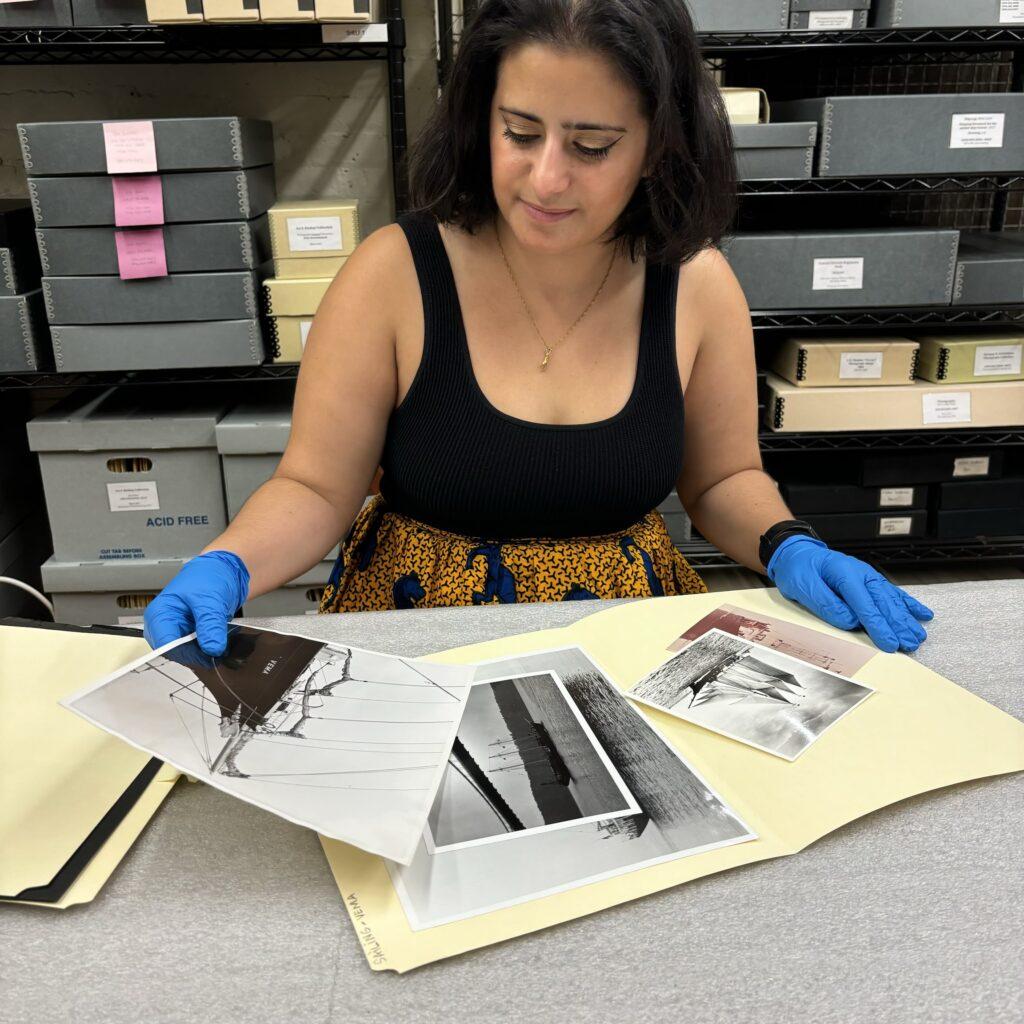

By Elena Abou Mrad, Archives and Special Collections Specialist

July 19, 2024

When people ask me what it’s like to be an archivist, I often reply: “It’s like being a detective, but for people who died a long time ago.” As a fan of Sherlock Holmes novels and murder mystery parties, I see the research component of archiving as an investigation of sorts. When processing an archival collection, there are so many unknowns: Who was the creator of this collection? Where were they from? What was their life like? These questions are important to decide how to rearrange the materials and to write a finding aid, the essential document that works as a summary of an archival collection. Well, as you can imagine, it’s hard to get the answers when the creator of this group of photographs is no longer among us. Then, where does one start?

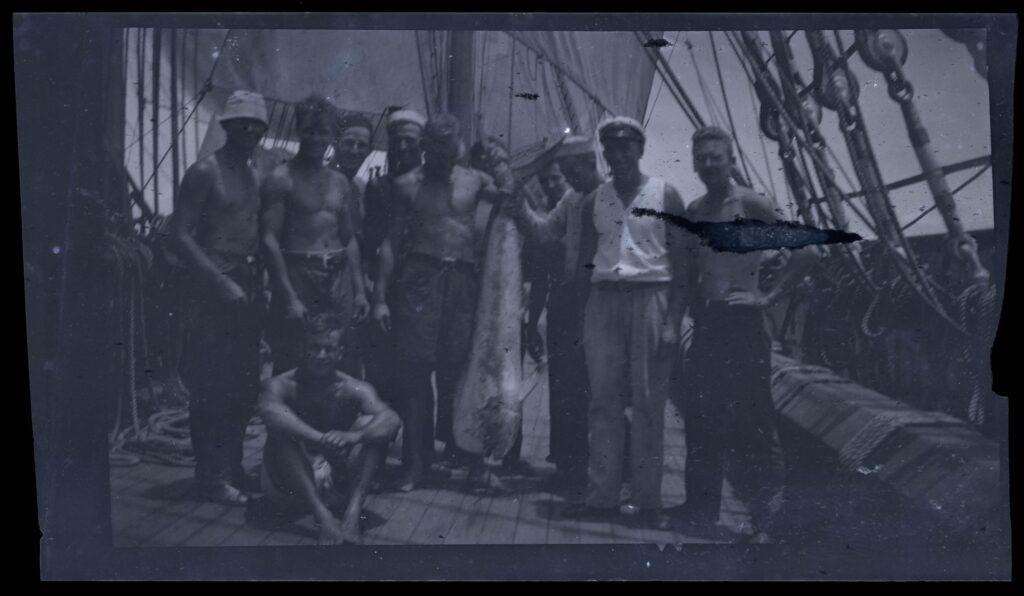

I found myself in this situation when I started to process the Captain Frank Ley Collection, the first project I’ve embarked on since starting as Archives and Special Collections Specialist at the South Street Seaport Museum. This collection was donated in 2023 by Terry Walton, one of the founding trustees of the South Street Seaport Museum and the founding editor of Seaport Magazine[1] South Street Seaport Museum published the South Street Reporter from 1967 to Summer 1978, and the Seaport magazine from Fall 1978 to 2010.. Frank Ley was her “honorary uncle,” a family friend whom she remembers fondly. The collection consists of 21 black and white photographic prints and 197 negatives depicting life at sea on the vessels Tusitala[2]Tusitala was a 261-foot square-rigged ship built of iron in 1883. She was the last ship built by the famous R. Steel shipyard in Greenock, Scotland, and was the first used in the wool trade between … Continue reading, Selma City[3]SS Selma City was built in 1921 by Chickasaw Shipbuilding & Car Co. in Chickasaw, Alabama for US Steel Products Co. of New York. In 1930 she was sold to the Isthmian Steamship Company of New … Continue reading, Vema[4]Vema was a three-masted sailing schooner built in 1923 by the shipyard Burmeister and Wain in Copenhagen, Denmark. She was commissioned by American financier Edward Francis Hutton for his wife, … Continue reading, and Seven Seas[5]The full-rigged ship Seven Seas was built in 1912 by Bergsund M.V. Atkieb, Stockholm, Sweden, for the Swedish Navy as the training ship Abraham Rydberg. The ship was acquired by the US Navy on April … Continue reading. The timespan of these images is approximately from the 1920s to the 1940s. The Captain Frank Ley Collection is of particular interest to the Seaport Museum since it documents life aboard sailing ships that are comparable to the 1885 tall ship Wavertree: by learning more about these vessels, we can learn more about the flagship of the Museum fleet.

The main challenge of this collection is that we do not have much information about these photographs and negatives, apart from what was written on the back of the photographic prints or on the envelopes that contained the negatives. In a not-so-fun turn of events, some of these envelopes had opened and the negatives had fallen out, which means we cannot be 100% sure of what they are depicting until we do more research.

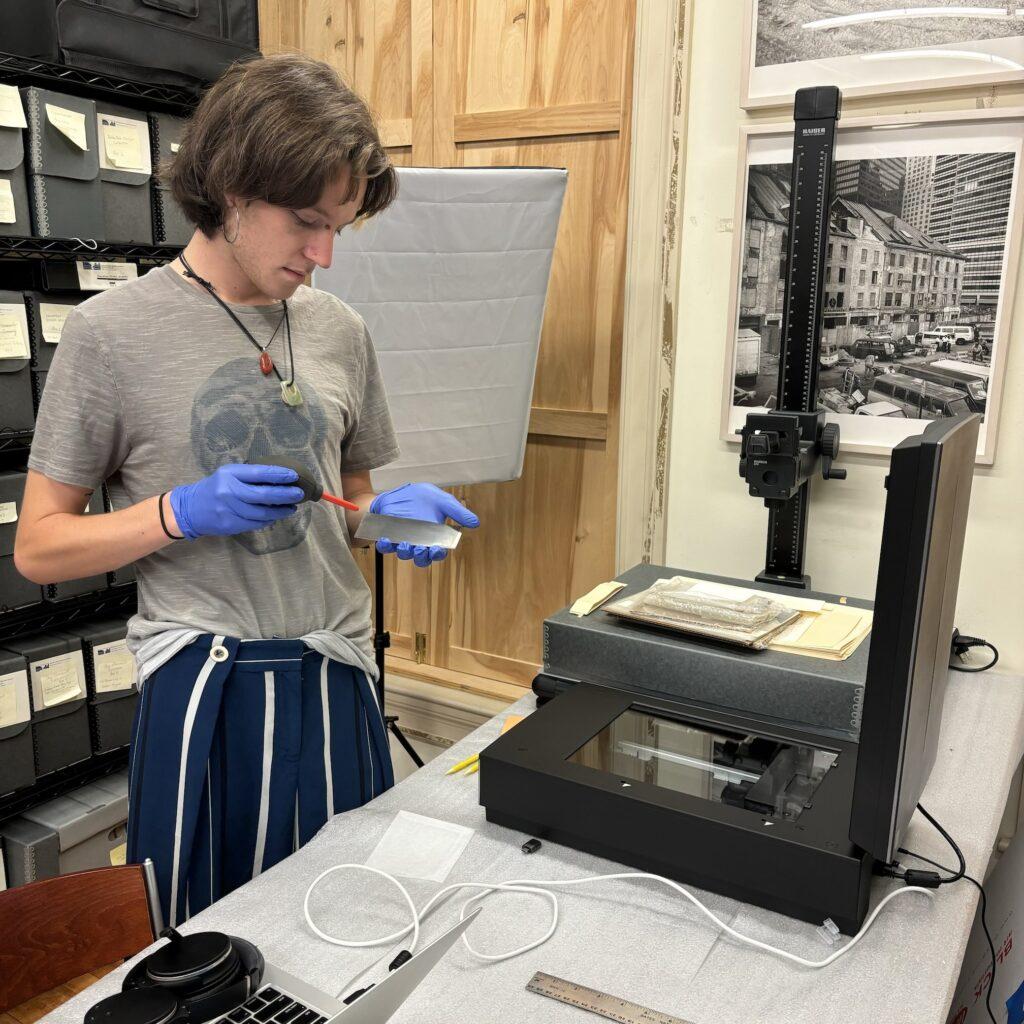

Together with this Summer 2024 Intern, River Smith, I am in the process of digitizing these photographs and negatives, describing them in the collection management database, and creating a finding aid for the collection. Even when looking just at the photographic prints, it is clear that we’re in front of something special.

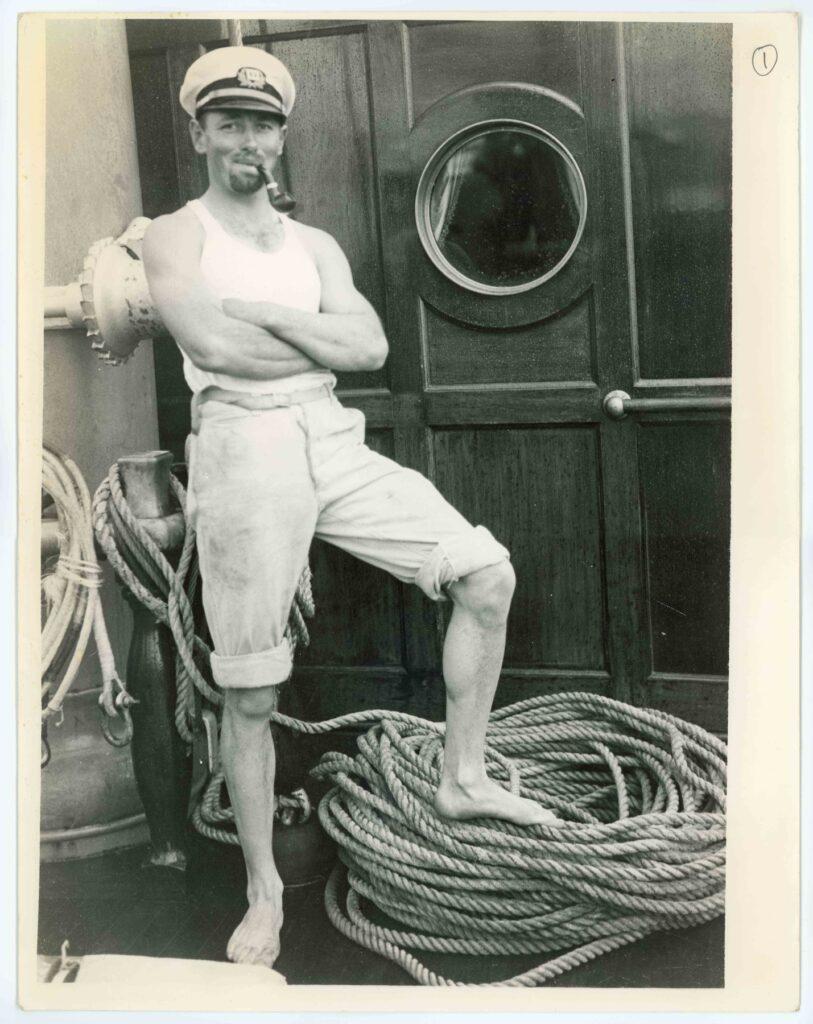

Portrait of Frank Ley on board Vema, n.d. (original ca.1935-1940s). Photographic print. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0001

The first print, for example, depicts a sailor standing on the deck of a ship, with a foot resting on coiled rope. He is smoking a pipe and staring directly into the camera. It’s just one photograph, but it drew me in and made me so curious to learn more about this collection. In this Collections Chronicles blog post, I will describe the research process I went through to find more information tied to the Captain Frank Ley Collection, not shying away from the meanderings that research often follows, and the dead-ends it encounters.

Step 1: Collecting evidence

Before even starting with the research, I needed to take a good look at what I already had in terms of information. Luckily, this was a very good starting point. When an archival collection gets acquired, the Museum’s Registrar asks and collects from the donor all the relevant documents into an accession file folder (printed and digital). Documents usually include deeds of gifts, appraisals, conservation reports, images, and any other personal note related to the items donated.

In this case, I had a deed of gift signed by Ms. Walton, correspondence with Frank Ley and his son from the 1980s, an article Walton wrote about her “honorary Hungarian uncle,” and even a photograph of the two together in San Francisco. The accession file also includes notes by Norman Brouwer, the Museum’s former historian (1972–2000s) about his conversation with Frank Ley and his stories from sailing on board Tusitala.

Another great piece of evidence was the photocopy of a newspaper article from the San Francisco Chronicle: it mentioned an oral history project that Frank Ley was a part of. I could already see myself going into 100 different research rabbit holes.

Step 2: Searching for information

As we started digitizing the photographs and negatives, I realized that in order to date them, I had to learn more about the history of the ships that were mentioned. This started extensive internet research, giving me some date ranges for each ship, together with details of their history and appearance. For example, I found plenty of information on Tusitala from the US Coast Guard, the Seamen’s Church Institute Archives, and sjohistorie.no, a Norwegian website dedicated to sea history.

While researching Vema, I even found a wonderful online exhibition: Voyages of the R/V Vema. Created by the American Institute of Physics (AIP), the exhibition tells the story of how Vema became a research vessel after World War II through maps, clips from oral history, and archival photographs.

Finally, I searched the Museum Maritime Reference Library’s photo archive for images of the ships portrayed in Captain Frank Ley Collection—this way, I would have additional visual references I could use to confirm the name of a ship in a certain photograph or negative.

Left: Intern River Smith removing dust from negative prior to digitization.

Center: Sampling of Maritime Reference Library publications used for research.

Right: Elena Abou Mrad looking through the Maritime Reference Library photo archive materials.

Searching for people is a little different: Frank Ley took his mother’s last name—which makes it harder to look him up on the internet. In general, I always try to find an obituary as it is a great place to start, because it offers a summary of someone’s life, information about their family, and dates of birth and death. Unfortunately, I could not find an obituary for Frank Ley; the most I came up with was his son’s obituary, from which I could at least find the names of Ley’s wife and children. I tried to look at ancestry.com, US military records on fold3.com (Ley had been in the army for one year), and one of my favorites online sites for research: findagrave.com.

My research came up empty: I would have to piece together a timeline from other sources of information. On the other hand, Find A Grave proved helpful in researching another prominent person in Frank Ley’s life at sea: James Platt Barker (1875–1946), the captain of Tusitala.

Step 3: When in doubt, ask a librarian!

The San Francisco Chronicle article I found in the accession file mentioned that Frank Ley recorded an oral history interview with the San Francisco Maritime Museum[6]The San Francisco Maritime Museum was operated by the San Francisco Maritime Association until it was transferred to the National Park Service in 1978. In 1988 Congress established San Francisco … Continue reading in 1975. Bingo! I decided to give this research path a try. I emailed the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park asking for information about Frank Ley’s oral history: within a week, Reference Librarian Gina Bardi and Archivist Lauren Bianchi had sent me not only the digitized audio files, but also scans of the typed transcripts. A treasure trove of information had just been delivered to me.

As an archivist, oral history gets me excited: it is a unique way of collecting information about a person, and most of all, it’s in their voice. Oral history captures what other types of records can’t: someone’s accent, for example. In Terry Walton’s words, Frank Ley had a Hungarian accent, which is reflected in the recordings from the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. I noticed his accent in the way Frank Ley pronounced “V” as “W,” so that the name of the schooner Vema sounds more like “Wema.”

While listening to the oral history, I was fascinated by Frank Ley’s humor, his detailed memories, and his great love of life at sea. In the recordings, he describes ship’s components in the most minute details, going as far as drawing sketches to better explain how the storm sails were folded or how the crewmen would haul the cargo with a “buddha” (a Buda engine[7]Practical hand book of gas, oil and steam engines, stationary, marine, traction; gas burners, oil burners, etc.; farm, traction, automobile, locomotive; a simple, practical and comprehensive book on … Continue reading). In another unexpected stroke of luck, Ley seems to be showing photographs to the interviewers—could these be the same photographs and negatives that River and I were digitizing?

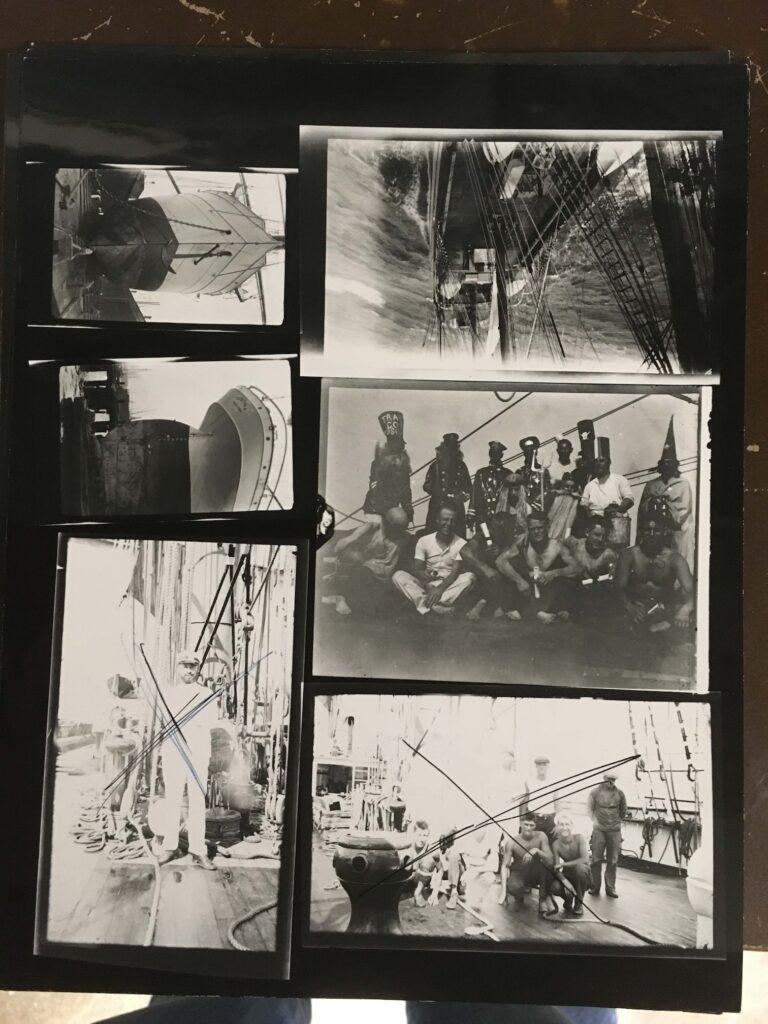

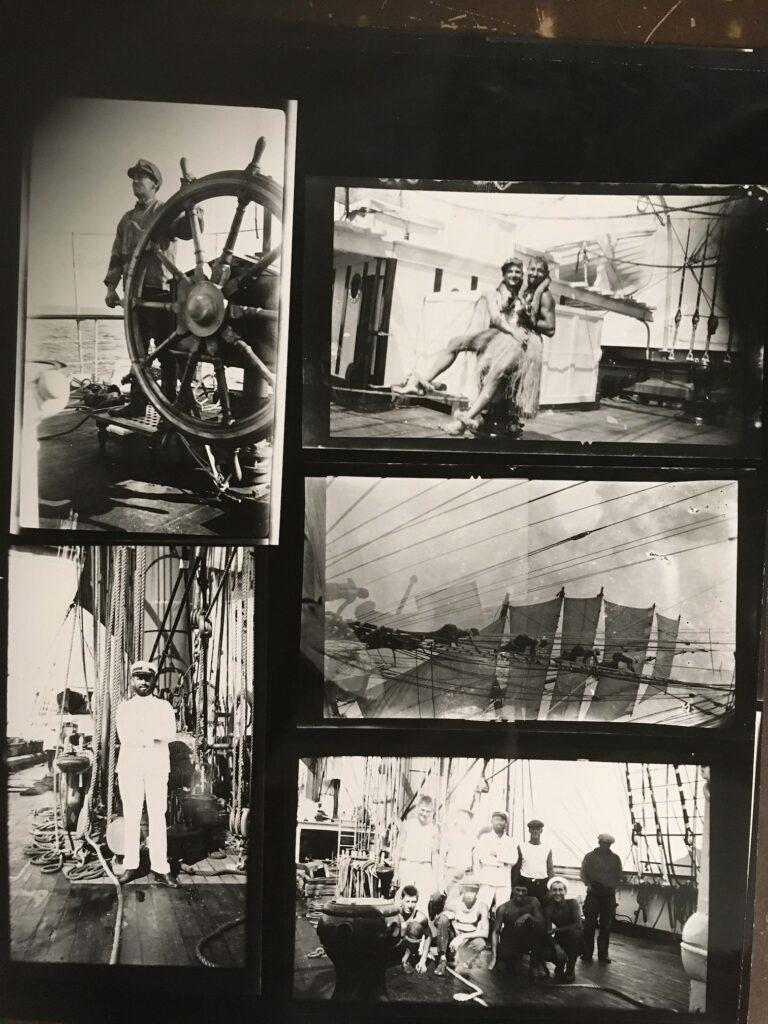

A few weeks after receiving the oral history files, Gina sent me the equivalent of a Rosetta Stone for the Captain Frank Ley Collection: 14 contact prints, with captions on the back. As soon as I opened the first file, I cheered: those contact prints corresponded to the negatives we were digitizing! Now, I had more information to interpret the negatives, including the people who appear in them and what actions they are performing; moreover, I would be able to connect the negatives to the stories mentioned in the oral history tapes.

Tusitala (built 1883; full rigged ship, 3m) views, 1923-1939. Contact sheets. Courtesy San Francisco Maritime NHP, No. J09.28903.

Unexpected discoveries: fun stories from the oral history

In the age of airplane travel, it is hard to imagine that a trip from New York to Honolulu would take seven months—without GPS, telephones, or refrigerators. Together with his photographs and negatives, Frank Ley’s oral history paints a vivid picture of life aboard Tusitala. Ley describes what he and his mates ate, what they did in their spare time, and how they interacted with each other on the long journeys. Can you imagine being in close quarters with your coworkers for months at a time?

Excerpt from Interviews with Frank Ley, July 24 1975 – August 6, 1975. Courtesy San Francisco Maritime NHP, G 540 T1.

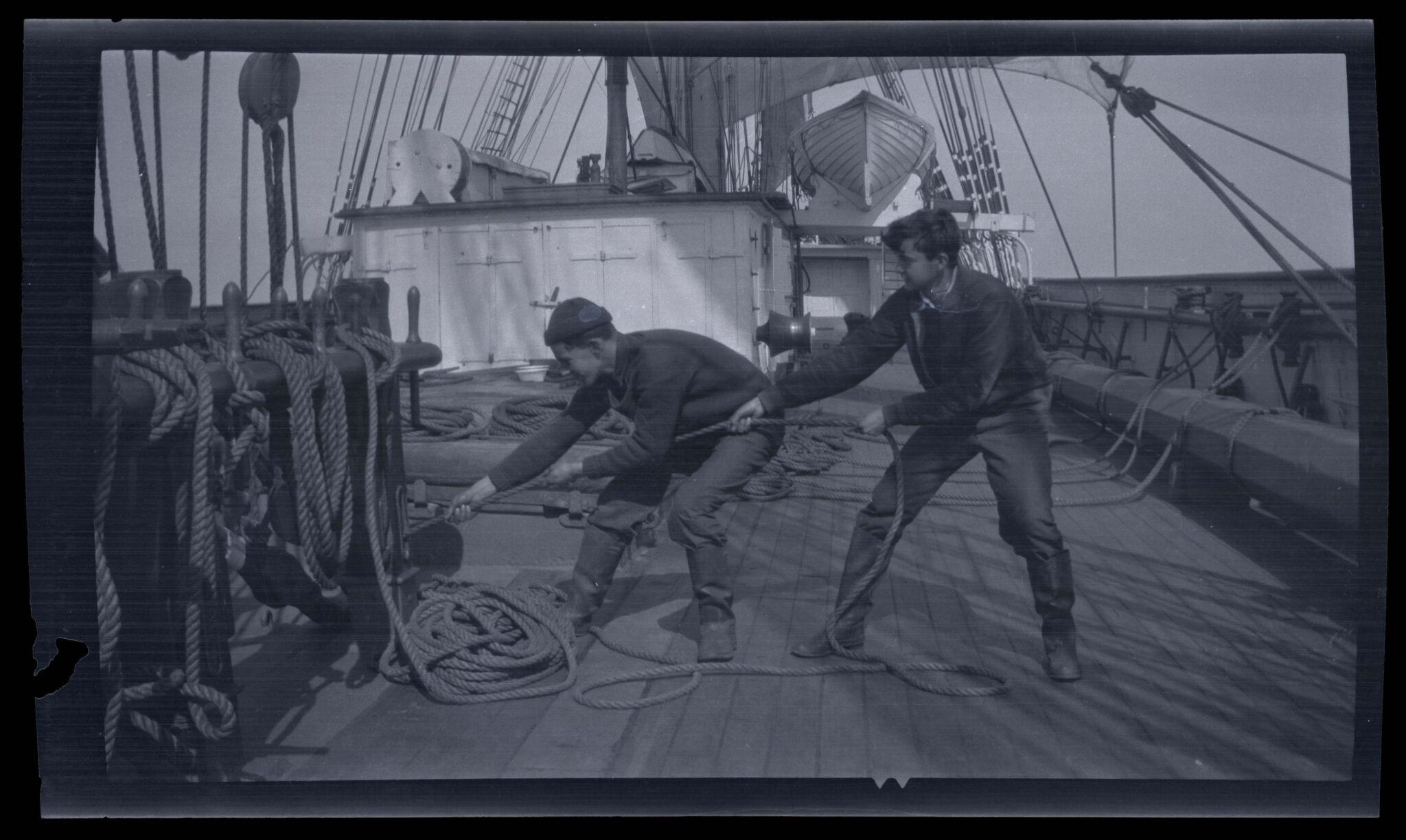

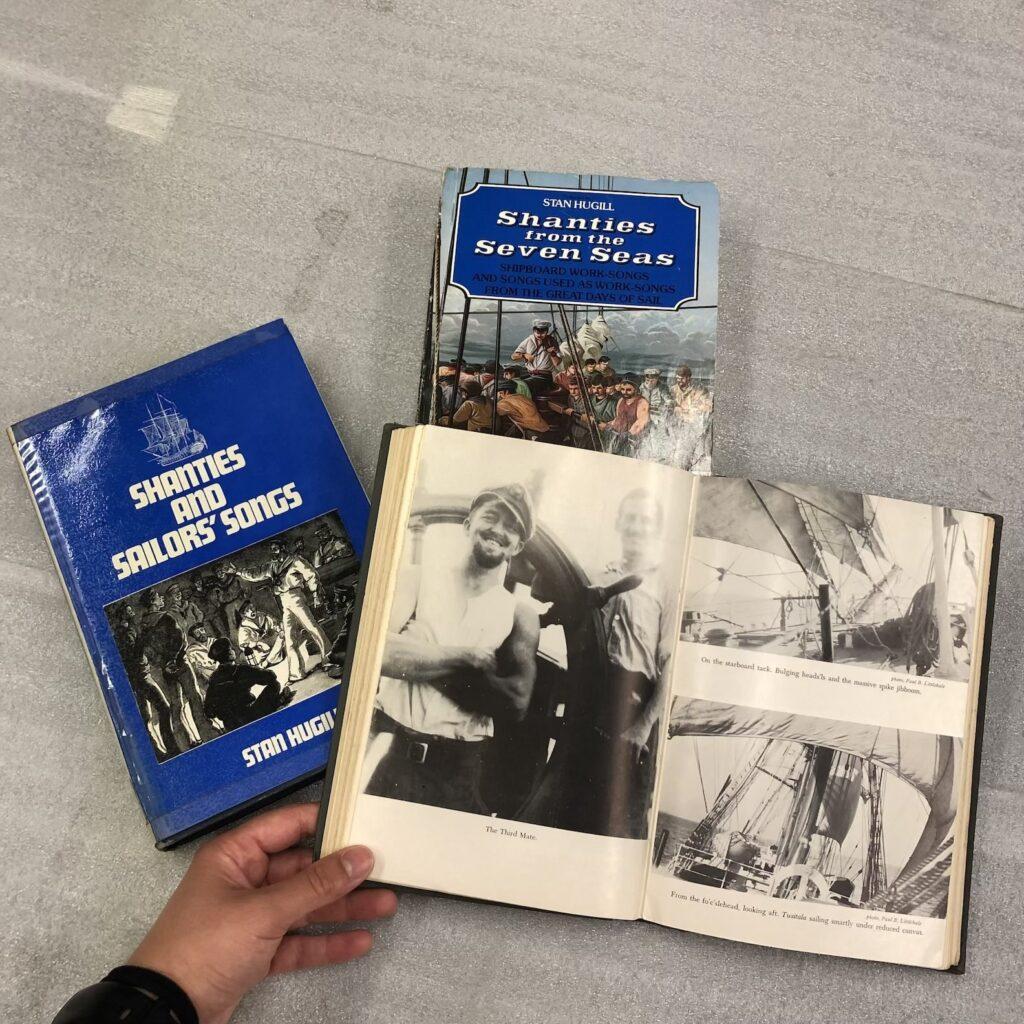

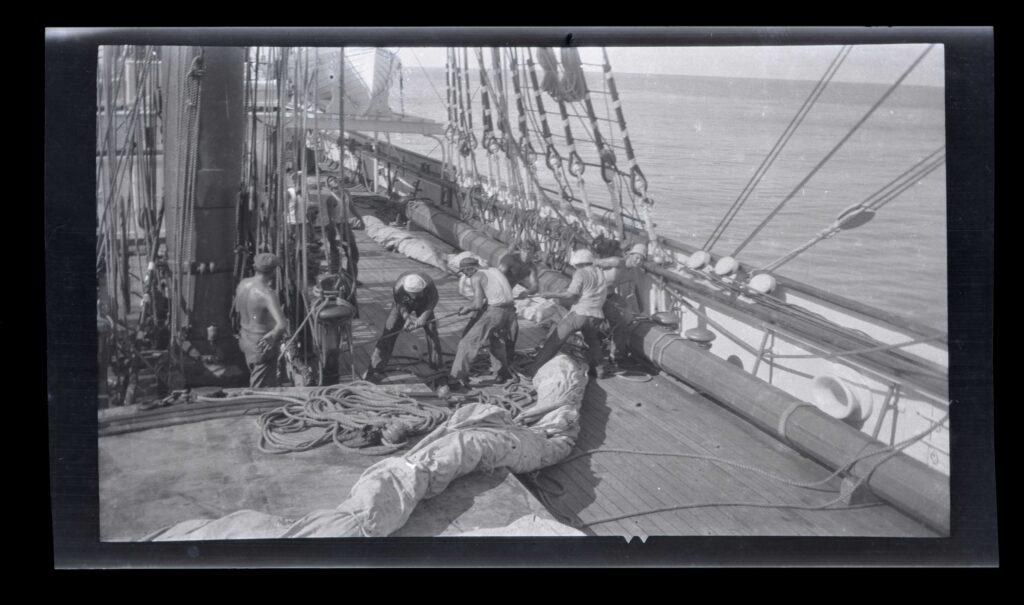

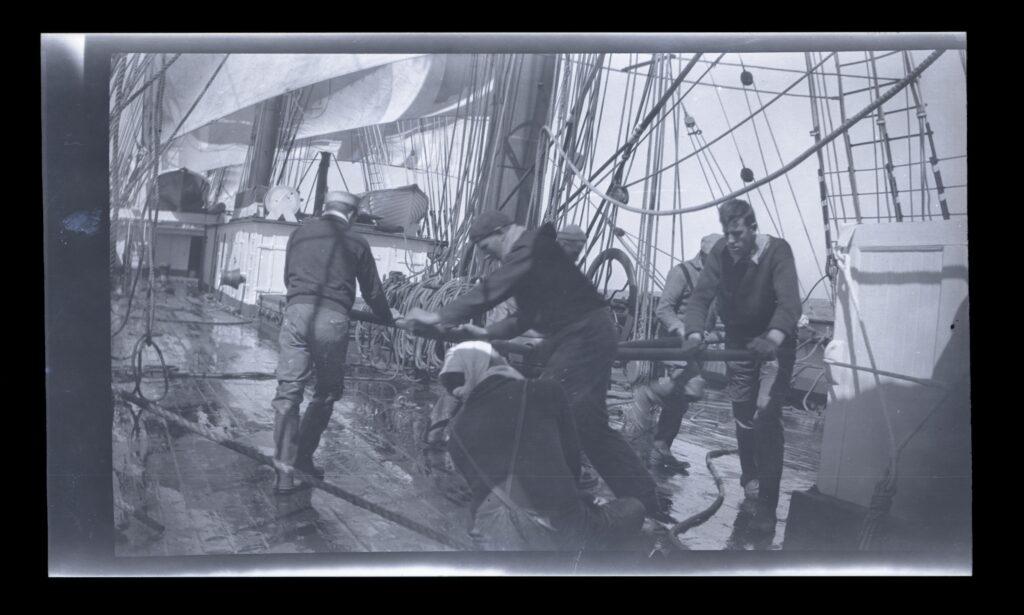

Sailing on a merchant ship involved a lot of teamwork: the crew had to act in unison to perform heavy tasks such as hoisting sails, hauling lines, and turning the capstan. In order to follow the same rhythm, sailors would sing sea chanteys[8]The first historic record of a sea chanty can be found in a manuscript from the time of Henry VI. This record mentions the passage of a ship full of pilgrims towards the port of Santiago de … Continue reading, the typical work songs aboard sailing vessels.

[Crew hauling on a line on Tusitala‘s deck], 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0052

An advantage of oral history is that we have a recording of Frank Ley singing the sea chanteys that he and his mates used on Tusitala. “Whiskey Johnny” was used while raising the jibs and the royals in three fast pulls.

The topsail yards were heavy, and it would take the crew half an hour to pull them: for this task, they would sing “Blow the Man Down,” a chantey conducive to long, slow pulls. In the second audio clip, Frank Ley also mentions the sea chantey “Renzo was no sailor” and sings “Johnny’s Gone to Hilo”.

Excerpt from Interviews with Frank Ley, July 24 1975 – August 6, 1975. Courtesy San Francisco Maritime NHP, G 540 T1.

[Crew walking round Tusitala’s capstan], 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0050

One detail that surprised me was the wide age range of the seamen aboard Tusitala: “green” youngsters who had never been at sea before worked alongside older men—one crewman was in his seventies! Apparently, this older seaman used to get so drunk on shore leave that his mates had to bring him back to the ship in a two-wheeled cart.

In this negative you can see a sailor is holding a cat and a dog in his arms. From a caption on the back of the contact print, we know that this is Prince, the ship’s dog.

According to Ley, the little mutt behaved like he was part of the crew: “he had to do what the others did. He understood every damn thing.” When the sailors pulled on a rope, he would grab the tail end and help. At night, the ship’s “policeman” would blow two whistles to wake up the watch on deck: Prince knew what the signal meant, and would bark and yip to wake up the crew.

[Sailor holding a cat and a dog on Tusitala‘s deck], 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0084

The little dog was no stranger to mischief: when Captain Barker took a nap, Prince would go past the mizzenmast on the weather side, which was “skipper’s country” and traditionally off-limits to the crew. Once, the captain pretended to scold the dog for his disobedience: without missing a beat, Prince looked the captain in the eye, cocked his leg, and proceeded to urinate all over the captain’s quarters. Ship’s dogs are not always good boys!

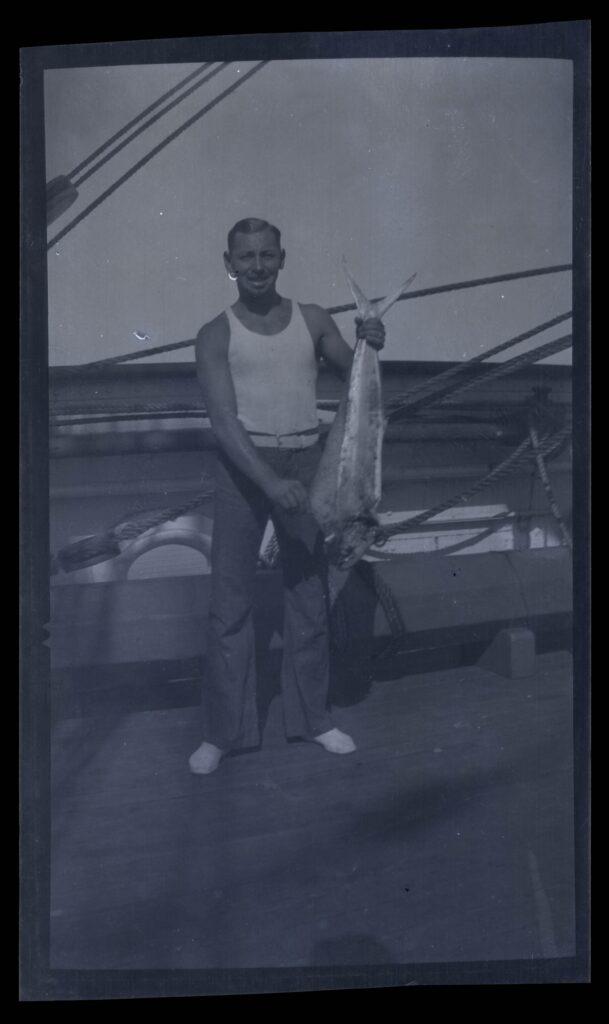

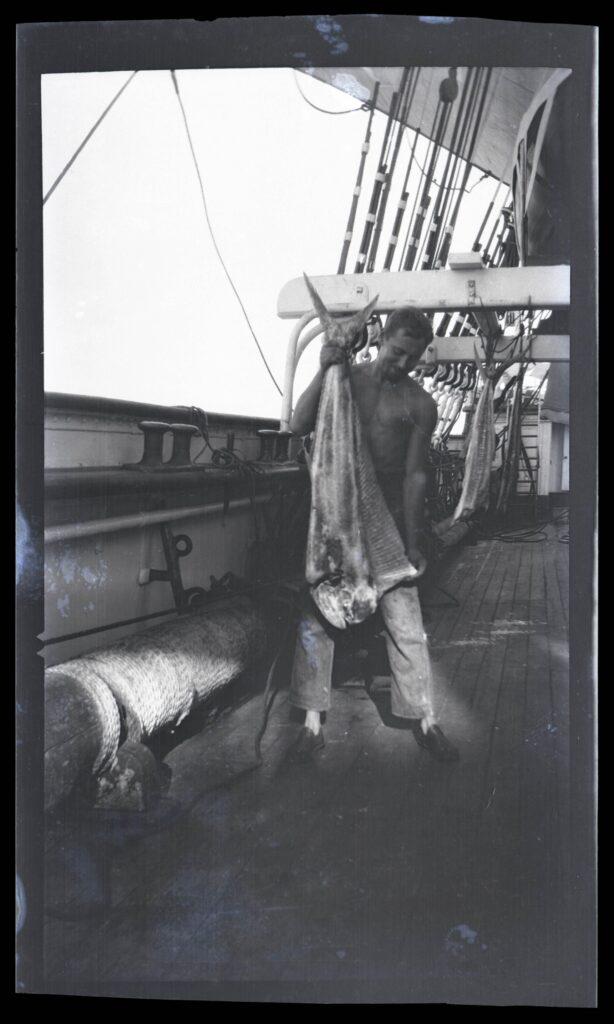

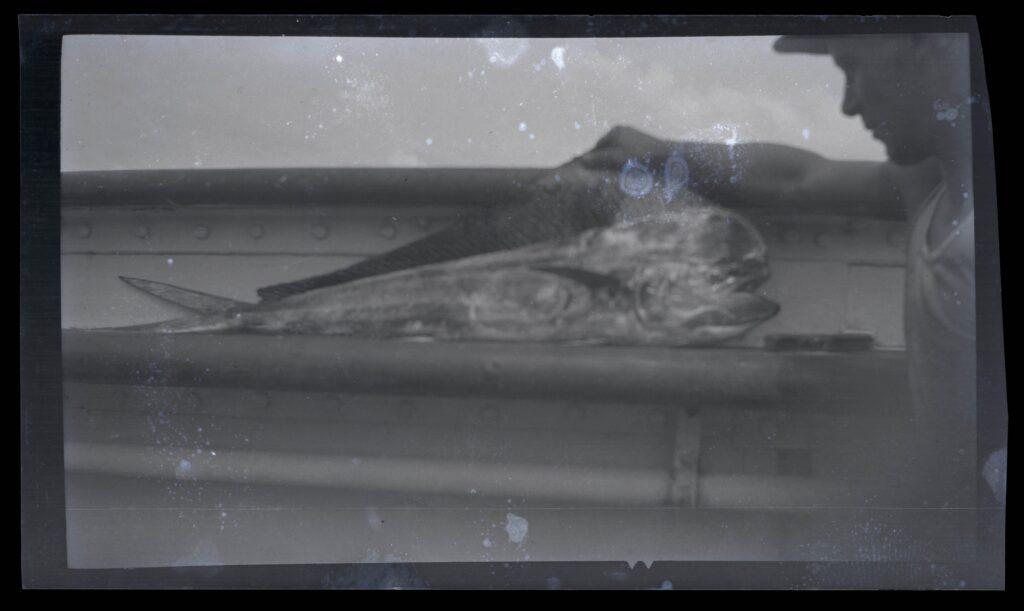

As I was listening to the oral history interview, one topic in particular spiked my interest: food. Frank Ley talks at length about what he and his crewmates ate on their long trips aboard Tusitala. The crew had barrels of salt pork and beef, and they stored cabbage, carrots, onions, and potatoes. The ship’s cook would bake bread every day, and sometimes he would even make hotcakes. Without refrigeration on board, the only fresh food available was what the sailors could fish in the Pacific Ocean.

[Sailor holding a fish on Tusitala‘s deck], 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0087 and 2023.007.0089

They weren’t too picky, either! According to Ley’s interview, they would fish bonita, albacore, tuna, mahi mahi, and even dolphins. In the negatives from the collection, we can even see the crew posing with a sea turtle and hauling a shark on board. In one of the negatives, a seaman is extracting fish from a shark’s stomach.

Left: [Sailor holding a fish along Tusitala‘s gunwale], 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0088

Rigtht: [Tusitala‘s crew posing with a large fish] 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Captain Frank Ley Collection, Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0090

Rewards of Research

While doing the research for the Captain Frank Ley Collection, I was reminded of why it’s important to spend time looking for information, even if it can be a lengthy process—and sometimes, a frustrating one. The hours spent scouring the internet, contacting fellow cultural institutions, and listening to long audio files are worth it when one looks back at the collection. Now, I don’t see only photographs and negatives—I see stories. I can imagine the sailors singing sea chanteys while at work, the cook preparing one of the giant fish that the crew caught, and the mischievous dog Prince running around the ship.

Working on the Captain Frank Ley Collection has also taught me that research doesn’t have to be a solitary endeavor: collaborating with fellow maritime museums can be extremely helpful. In this case, it felt like the Captain Frank Ley Collection was in conversation with the archival materials from the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. This kind of fruitful collaboration is the result of the efforts of organizations that work to develop a network of maritime museums, more nationally and locally with the Council of American Maritime Museums (CAMM) and internationally with the International Congress of Maritime Museums (ICMM).

The purpose of research is not only to find more information, but to use that information to give depth to the archival materials, so they could be shared with various departments within the Museum for educational use, and external researchers as needed. The Captain Frank Ley Collection was a great project to inaugurate my new position at the Seaport Museum, and I am looking forward to many more archival adventures.

Additional readings and resources

Voyages of the R/V Vema, American Institute of Physics.

Records of the Ship TUSITALA, Manuscript Collection 72. Mystic Seaport Museum.

The Last Square-Rigger (The Saga of the “Tusitala”), by Edmund Francis Moran. The Lookout, Seamen’s Church Institute of New York, June 1951, pp. 7-8.

Tusitala by Roland Barker. [1st ed.] ed., Norton, 1959.

Shanties from the Seven Seas : Shipboard Work-Songs and Songs Used As Work-Songs from the Great Days of Sail by Stan Hugill. 2nd (abridged) ed., Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984.

Shanties and Sea Songs, by John Ward, 2013.

References

| ↑1 | South Street Seaport Museum published the South Street Reporter from 1967 to Summer 1978, and the Seaport magazine from Fall 1978 to 2010. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Tusitala was a 261-foot square-rigged ship built of iron in 1883. She was the last ship built by the famous R. Steel shipyard in Greenock, Scotland, and was the first used in the wool trade between England and Australia. In 1923, the ship became the private yacht of the US Steel Corporation’s President James A. Farrell (1863-1943) under the name Tusitala. Before 1923, the ship names were Inveruglas (1883-1886), Sierra Lucena (1886-1906), and Sophie (1906-1923). In 1925, Mr. Farrell asked Captain James Platt Barker (1875-1946) to command Tusitala for runs between Honolulu and New York as a commercial carrier. Tusitala was America’s last full-rigged merchant ship. In 1939 she was acquired by the United States Maritime Commission and became a training ship for merchant seamen. During World War II, she was stationed at St. Petersburg, Florida. On October 14, 1947, Tusitala was sold, under the hammer of the United States Marshal. The Pinto Island Metals Corporation of Mobile, Alabama, purchased her for 16,176 USD. Her scrapping was completed on April 1, 1948. |

| ↑3 | SS Selma City was built in 1921 by Chickasaw Shipbuilding & Car Co. in Chickasaw, Alabama for US Steel Products Co. of New York. In 1930 she was sold to the Isthmian Steamship Company of New York, and remained their vessel until her disposition in 1942. On April 6, 1942, she was attacked by Japanese bombers in the Bay of Bengal, India, causing her to sink the day after, on April 7, 1942. |

| ↑4 | Vema was a three-masted sailing schooner built in 1923 by the shipyard Burmeister and Wain in Copenhagen, Denmark. She was commissioned by American financier Edward Francis Hutton for his wife, Marjorie Merriweather Post, and was originally named Hussar. In 1932 she was sold to the Vetlesen shipping magnates and renamed Vema. She broke a trans-Atlantic sailing record that year, from New York to England in just under eleven days. Vema was donated to the US government during World War II and functioned as Coast Guard patrol boat and merchant marine training vessel. In 1953 she was purchased by the Director of the Lamont Geological Observatory, to become a scientific research platform. During its nearly 30 years of service at Lamont, Vema collected an unprecedented range of geophysical and oceanographic data. The work she allowed became foundational in the study of geophysics and oceanography, and provided crucial evidence for the rapidly coalescing theory of plate tectonics. In March of 1981, Vema was decommissioned by Lamont-Doherty, and the year later, Captain Mike Burke, the founder and owner of Windjammer Barefoot Cruises, acquired Vema and re-named her Mandalay. Ultimately, Vema was restored to its earlier form as a sailing schooner, and in recent years has operated recreational cruises in the Caribbean. |

| ↑5 | The full-rigged ship Seven Seas was built in 1912 by Bergsund M.V. Atkieb, Stockholm, Sweden, for the Swedish Navy as the training ship Abraham Rydberg. The ship was acquired by the US Navy on April 10, 1942, renamed Seven Seas, and placed in service on May 5, 1942. Seven Seas assumed duties as station ship at Key West, Florida, and remained there until after the heyday of World War II’s coastal U-boat strikes. In May of 1944, as the dangers lessened, she was placed out of service and laid up at the Coast Guard Patrol Base of Port Everglades, Florida. Seven Seas was struck from the Navy list on July 29, 1944. The ship final disposition is unknown. |

| ↑6 | The San Francisco Maritime Museum was operated by the San Francisco Maritime Association until it was transferred to the National Park Service in 1978. In 1988 Congress established San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. |

| ↑7 | Practical hand book of gas, oil and steam engines, stationary, marine, traction; gas burners, oil burners, etc.; farm, traction, automobile, locomotive; a simple, practical and comprehensive book on the construction, operation and repair of all kinds of engines. by John B. Rathbun, [from old catalog] Chicago, Charles C. Thompson co. [c1916], |

| ↑8 | The first historic record of a sea chanty can be found in a manuscript from the time of Henry VI. This record mentions the passage of a ship full of pilgrims towards the port of Santiago de Compostela (Spain) in 1400: the writer reports the songs that the sailors sang while pulling on lines and raising the sails. Shanties from the Seven Seas, by Stan Hugill, p.2 |