A Look At New York City Through One Building With Multiple Identities

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Carley Roche, Collections and Archives Intern

July 23, 2020

New York City’s architecture is central to what makes it so iconic. From towering skyscrapers to well-loved taverns, New York City is filled with buildings of all shapes and sizes. The history of the city can be traced through the different styles of architecture that fill the avenues and streets.

One building that has served many roles throughout New York’s storied history is Castle Clinton. For centuries, this building has been used for protection, entertainment, and the start to a new life in America. Continue reading below to learn how a single location at the tip of Lower Manhattan has been renovated and reimagined over the years to fulfill the needs of an ever changing city.

War-Time Beginnings, 1808-1822

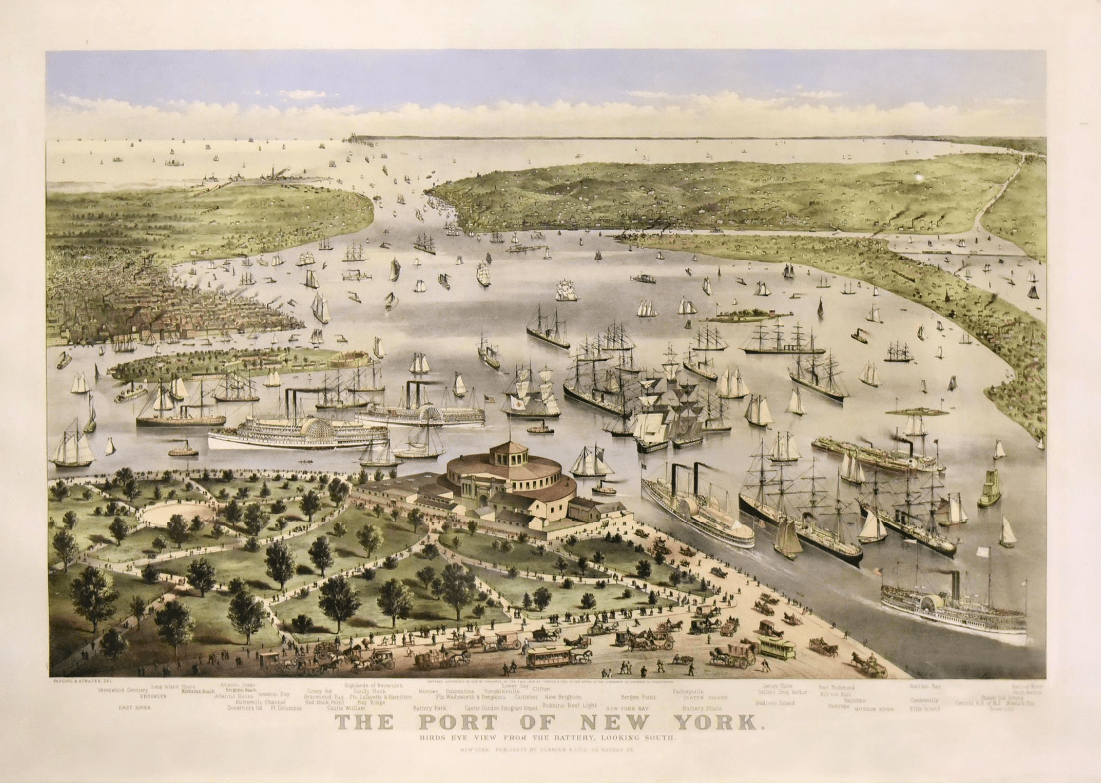

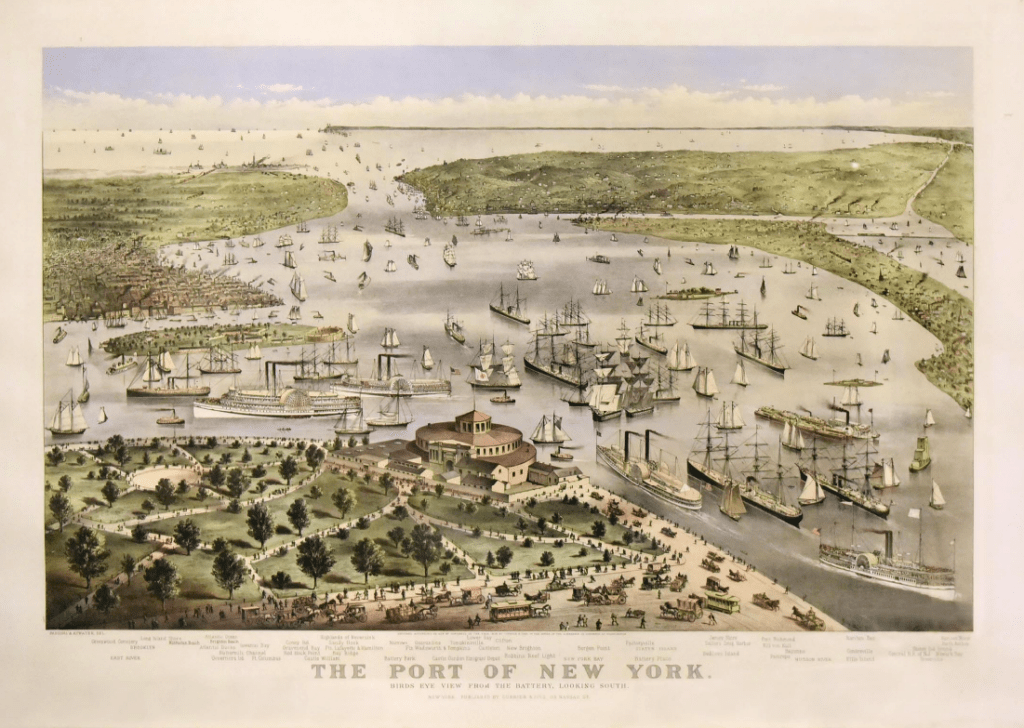

Tensions between the United States and Great Britain increased in the years leading up to the War of 1812. With the British attack on the USS Chesapeake, disputes over Northwest Territories, and the continued impressment of American soldiers, harbor cities agreed to build forts to protect American shores. Between 1808 and 1811, New York Harbor became the home to four new forts: Castle Williams, Fort Wood, Fort Gibson, and Southwest Battery.

The Southwest Battery was built just off the tip of Lower Manhattan. General Joseph Bloomfield gained command of all forts in New York City during the war and declared Southwest Battery as his official headquarters. Although armed with 28 cannons, Southwest Battery never needed to fire a single shot during the war- nor did any forts in New York Harbor. In 1815, after the fighting had ceased, Southwest Battery was renamed Castle Clinton in honor of Mayor DeWitt Clinton, later Governor of New York.

Entertainment Garden in the City, 1823-1854

After its military career Castle Clinton became the entertainment center of New York City.

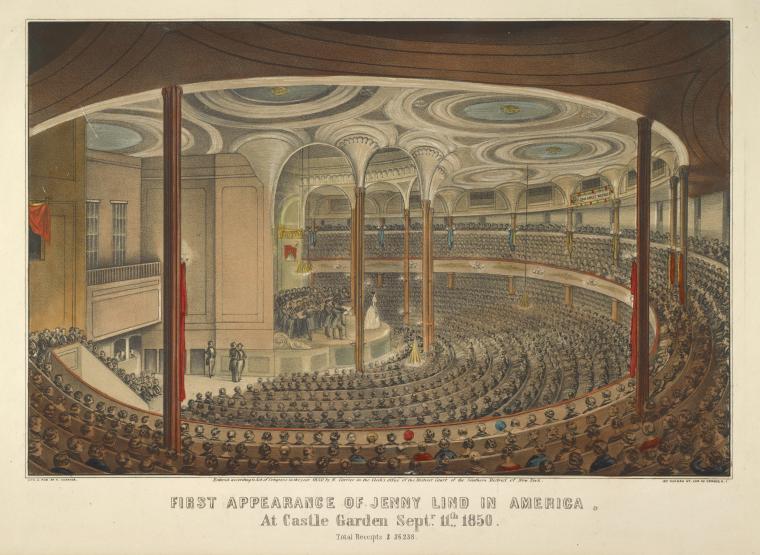

In 1823, the federal government decommissioned the fort then deeded it to the city. On July 3rd of the same year, Castle Clinton officially opened its doors to the public under its new name: Castle Garden. An amphitheater, an opera house, a restaurant and beer garden, an exhibition hall, and a promenade Castle Garden offered something for everyone who visited. Castle Garden hosted some of the most memorable performances of the age including the famous “Swedish Nightingale” Jenny Lind’s American debut, P.T. Barnum showcasing his circus act, and demonstrations of new inventions such as the telegraph.

A venue for art, culture, and science, native New Yorkers and far away visitors revelled in Castle Garden’s entertainment offerings sweeping the late 19th Century. To accommodate the growing number of visitors a second story, a balcony, and a roof were added to the original structure. For over 30 years, Castle Garden was the place to visit for the latest in amusement and scientific progress.

Immigration Processing Center, 1855-1890

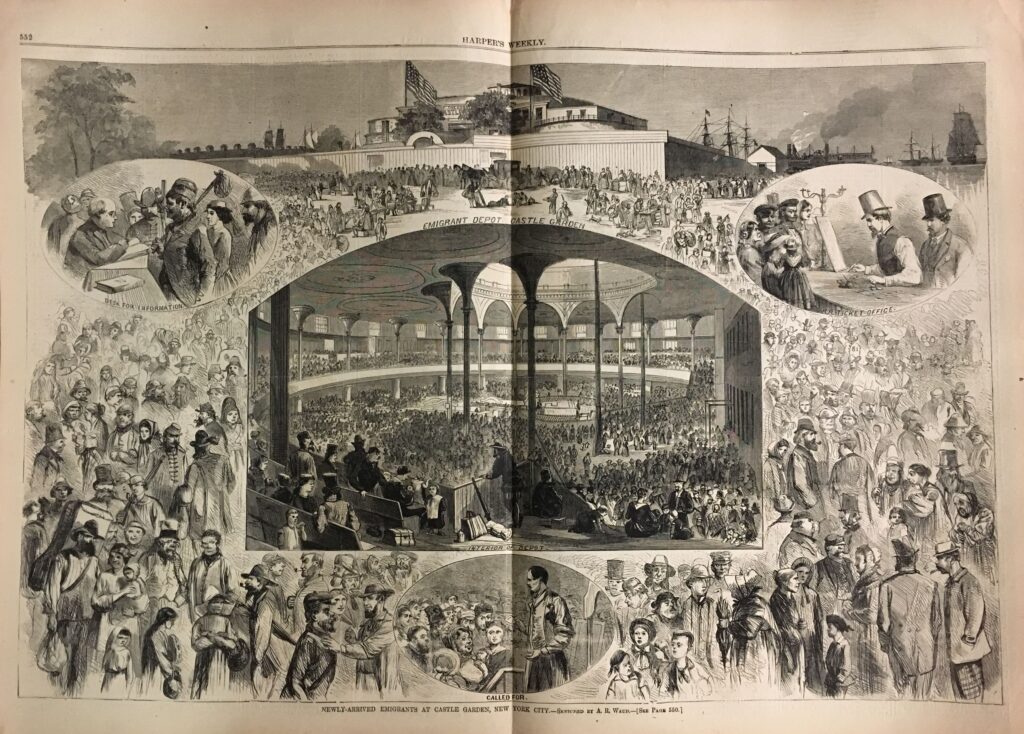

America had been welcoming immigrants from all over the world for decades, but as the number of new arrivals continued to exponentially rise and as new immigrants were taken advantage of at the docks New York’s government stepped in to establish some order. Thus the old leisure palace of Castle Garden was refurbished into the first official Emigrant Landing Depot in the nation.

On August 3, 1855, Castle Garden opened its doors to immigrants for processing, health examinations, and information related to potential further travel. The governments of New York City and New York State collaborated to collect detailed records of the over 8 million passengers who entered America through Castle Garden. Unfortunately, these documents were lost in a fire on Ellis Island on the night of June 15, 1897.

Two out of every three immigrants who came to America between 1855 and 1890 were processed at Castle Garden. Thousands of people arrived everyday, which led to chaotic crowds within the depot. The impact of Castle Garden can even be found in the Yiddish word Kesselgarden, which means “a confusing, noisy situation”[1] America’s First Immigration Center Was Also an Amusement Park, by Erin Blakemore . It soon became clear that this depot was not equipped with the right resources or space to handle the number of incoming immigrants.

Though many new immigrants would settle in New York City, for some it was only the point of entry to cities and farmlands farther west. Castle Garden became notorious for the solicitors and “sharpers” who waited outside to take advantage of newcomers. In 1873, to make sure immigrants could safely get to the New Jersey rail terminals, the Erie Railway negotiated a contract to run a ferry directly from Castle Garden. This ferry contract also secured immigrant business and revenue for the railroad company.

On this model you can read the words “Erie Eisenbahn” painted on the bow. This is the German translation of “Erie Railway” and reflects the large number of German-speaking immigrants to the United States in the 1870s and 1880s.

The federal government took over immigration policies, citing lack of resources and corrupt employees at Castle Garden, choosing Ellis Island as the new immigration depot of the United States. On August 18, 1890, Castle Garden’s term as an emigration depot ended.

New York City Aquarium, 1896-1941

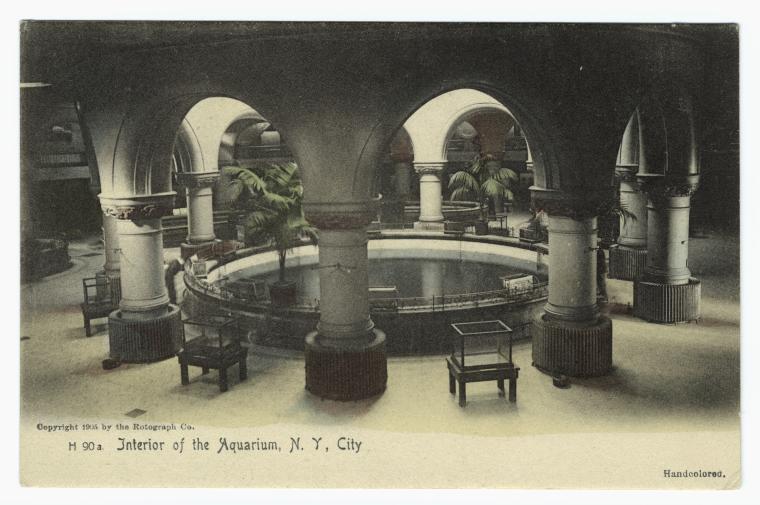

After Ellis Island became the new immigration processing center, Castle Garden returned to being a recreational venue with an added educational element. On December 10, 1896, the building welcomed over 30,000 visitors as the New York Aquarium. A very popular tourist attraction, the aquarium held over 300,000 gallons of water and 150 specimens including a beluga whale.

The construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel forced the aquarium’s relocation to Coney Island in 1941. The specimens were placed at the Bronx Zoo while the new aquarium site was under construction. On June 6, 1957, the New York Aquarium reopened on the Coney Island Boardwalk and still remains to this day making it the oldest continuously operating aquarium in America.

Near Demolition to Historic National Monument, 1941-Present Day

In 1941, Robert Moses, New York City Commissioner, called for the complete demolition of Castle Clinton because he found it to be an “ugly wart” with “no history worth writing about” [2] Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers, by James Nevius, and Michelle Nevius, p. 242 . His original plan to connect Brooklyn and the Battery with a new suspension bridge failed after public outcry and interference from President Roosevelt, so a tunnel was chosen instead. Despite losing the campaign to construct a bridge, Moses became slightly successful in demolishing Castle Clinton. It’s roof and additions from over the years were removed so that the fort’s original walls were all that remained standing. Further demolition was put off with America entering the Second World War.

After WWII, petitions to preserve Castle Clinton continued. On August 12, 1946, President Truman signed a bill declaring Castle Clinton a National Monument paving the way for its restoration. The building was finally ceded to the federal government on July 18, 1950. By 1975, the Castle Clinton National Monument had been restored by the National Park Service. Today, Castle Clinton stands in Battery Park as the departure point for visiting the Statue of Liberty. Filled with stories of new beginnings, innovation, and survival, Castle Clinton is a physical reminder of the broad history of New York City.

Sources

The Battery (2020). History.

New York Public Library Digital Collections. (2020). First appearance of Jenny Lind in America. At Castle Garden, Septr. 11th, 1850. Total receipts $26,238.

NYC Parks. (2020). History of the New York Aquarium.

Blakemore, E. (2017, Jan. 26). America’s First Immigration Center Was Also an Amusement Park. Smithsonian Magazine.

National Park Service. (2015, May 16). History & Culture.

National Park Service. (2015, March 12). Southwest Batter (Castle Clinton).

The New York Preservation Archive Project. (2016). Castle Clinton.

Nevius, J. & Nevius, M. (2014, April 15). Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | America’s First Immigration Center Was Also an Amusement Park, by Erin Blakemore |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers, by James Nevius, and Michelle Nevius, p. 242 |