A Seaport Museum Blog

by Laura Norwitz, Senior Director for Programs and Education

December 30, 2020

We are living in a year that will surely be one of the most studied in modern history. Who would have thought a year ago that we would be in this moment?

It began early last spring, as the pandemic reached New York. Casey Schott, our erstwhile Manager of School Programs, describes his experience:

“My last day physically in the office was Thursday, March 12. The threat of coronavirus, our new global pandemic, was becoming more and more of a reality. Earlier in the day, museums across the city announced that they would close their doors to the public for an indefinite amount of time. Now it was our turn to do the same.”

In the months since March 2020, our world has changed and changed again. A pandemic, an economic crisis, a social and historic reckoning… and now we are – still – in the middle of an election season like no other.

Through it, the South Street Seaport Museum has had to change the way it works with schools. How can we continue to offer quality, student-centered programming connecting participants with the Seaport during a pandemic?

A hallmark feature of our school programs is no longer available — experiential, place-based education. A field trip to Wavertree or Pioneer is more than the information shared during those visits; it is the experience of being on a ship, of feeling the movement of the deck, of straining on the capstan bar. We can’t transmit the smell of pine tar through a Zoom screen, or do justice to the vastness of Wavertree’s hold.

Yet there are other hallmarks of a Seaport Museum school program: engaging learners at all levels with rich questioning that encourages them to observe, think, and make connections, and to do so in lively discussions with their peers. And to contemplate the relevance of the Seaport to our history, and the connection of our themes to students’ lives today.

How do these hallmarks play out in our traditional walking tour?

Casey explains the process for our Revolutionary War Walking Tour:

“These aren’t your typical walking tours in which a tour guide takes a group around and says, ‘on this date, XXX happened here.’ Unlike Philadelphia and Boston, New York City is the city that is ever-changing and never standing still. Historical sites that look like the colonial era (or even 100 years ago, for that matter) are a rarity in New York. It can be tough to envision the history laid out on the street corners, when all you may actually see is a Starbucks, a Chase Bank, and a rack of Citi Bikes (as is the case for the site of the Battle of Golden Hill – which happened to also be right near the residence of Alexander Hamilton [1] https://www.urbanarchive.org/sites/fVJvfVSKaU6/wXpFnusHq2T ) We use maps, images, and activities to place the students in the context.”

Our Revolutionary War Walking Tour, like all our historic education programs, isn’t really about who-did-what-where. It is about more universal ideas:

- Who are New Yorkers, then and now?

- How did they respond to and participate in the events of their times, and how do New Yorkers respond today?

- How is the Seaport critical to New York life and history, then and now?

In our Revolutionary War Walking Tour, students imagine themselves as 18th century artisans, laborers, merchants, government officials, and free and enslaved Africans. They debate how the city’s role as a commercial center and port is affecting their imaginary selves. And they envision their supposed response to the current events swirling around them – including considering the responses of violent and symbolic protest which appealed to the Sons of Liberty.

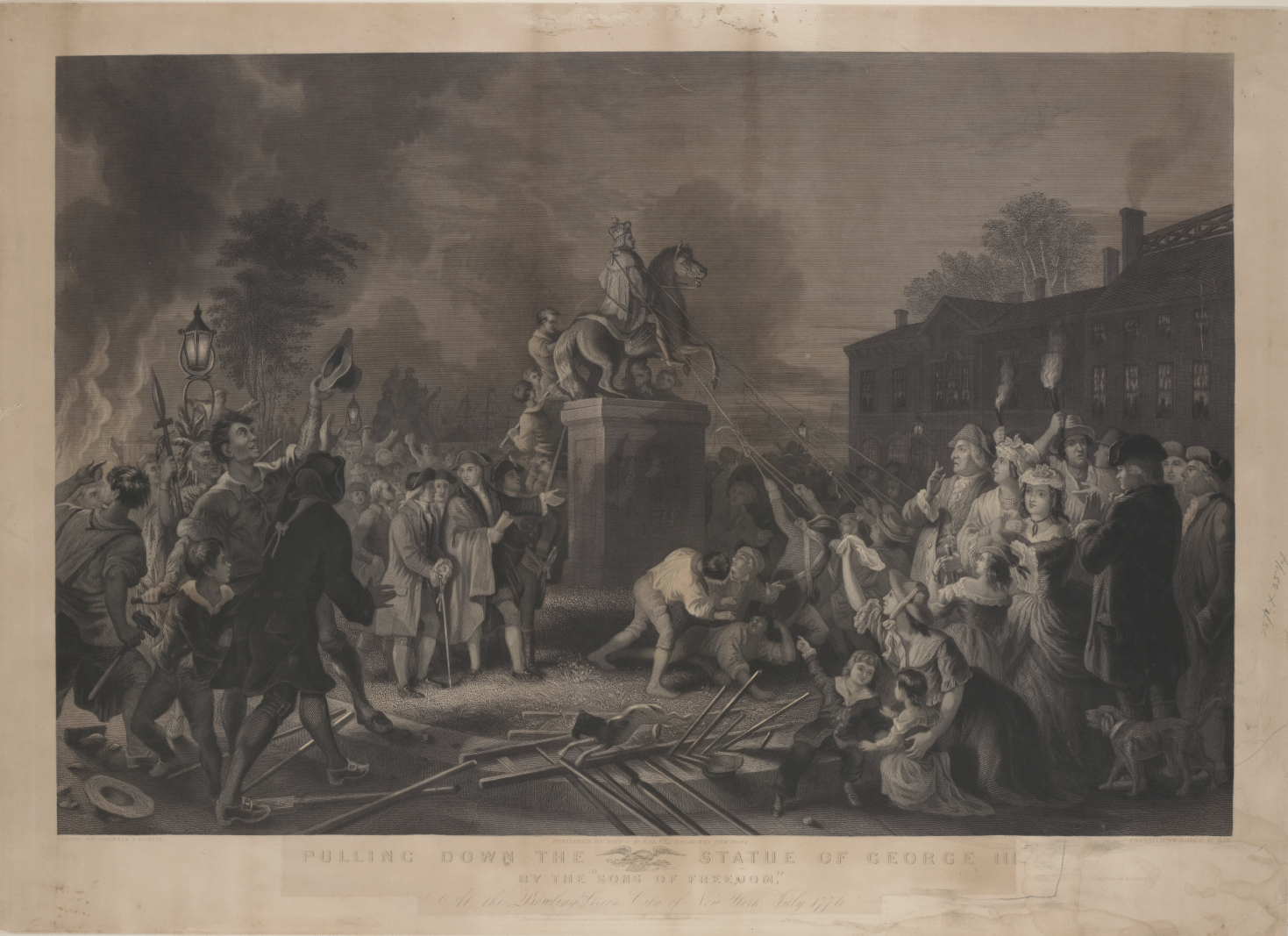

Casey goes on: “After hearing the Declaration of Independence read aloud in 1776, a group of riled-up New Yorkers marched down to Bowling Green and tore down the statue of King George III. Why did they do that? Did tearing down the statue actually hurt King George III? This symbolic act of aggression sent a clear message to British authorities, and rallied people together”.

Image at left: Tearing Down Statue of George III (The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1859). Tearing down statue of George III. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f56e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Adapting a Walking Tour in Troubled Times

In the spring of 2020, several schools had been scheduled to come to the Seaport Museum for the Revolutionary War Walking Tour. Once the pandemic hit, we began creating a virtual version for their teachers to use remotely.

And then the world changed, again.

“The ideas for our virtual program were already taking shape,” Casey recalls. “Then, on May 25th, George Floyd was killed after a police officer pinned him to the ground with a knee on his neck for 8.5 minutes. The following day the video went viral and protests erupted in Minneapolis condemning the killing of George Floyd. [2]https://www.nytimes.com/article/george-floyd-protests-timeline.html

By the following week, it felt as though the world were on fire. With the backdrop of a global pandemic, economic recession, and the wide awakening to systemic oppression and racism, I found it nearly impossible to focus on work-related matters. My mind was elsewhere, examining the privileges in my life as a cis-gendered white male, gathering resources on becoming an effective ally, and learning about how to promote social change by uplifting the voices around me and using my voice to speak out against systemic racial oppression.

“As the week went on and as the protests intensified, I watched Trevor Noah’s video on YouTube addressing reactions to notions of protest. [3]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4amCfVbA_c “There is no ‘right’ way to protest because that’s what protest is. It cannot be ‘right’ because you are protesting against the thing that is stopping you.” When we saw the images on TV of the damage caused by the riots or the stores that were looted, many viewers were quick to denounce the destruction. As I sat with these thoughts, parallels became clear between the current situation and the uprisings leading to the American Revolution.

“In our walking tour, we discuss the Stamp Act of 1765 and its impact upon different New Yorkers. Who was affected? How did they feel? If you were unhappy with the Stamp Act, how do you speak out? It’s always fascinating to see how many students are quick to suggest rioting. Hardly ever do students suggest a simple form of protest like not paying the tax. But how do you protest? I revert to Trevor Noah’s comment for that one.

On our walking tours, this conversation eventually leads to discussing the Sons of Liberty, the secret freedom fighters who opposed British authority and sometimes used violence and intimidation tactics to get their message across. When teaching history, how do we portray the Sons of Liberty? Are they the heroic freedom fighters? Do we omit their violent tactics?”

Our modern rash of protests did not end in May, or even the summer. Indeed, protests broke out again in Philadelphia, when another Black man, Walter Wallace, was killed by police in October,[4]https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/28/us/philadelphia-police-shooting.html and again when Casey Goodson Jr was killed by police in Columbus in December[5]https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/22/us/columbus-ohio-shooting.html.

And according to a recent article in Politico [6]https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/10/01/political-violence-424157 and New Yorker Magazine, [7]https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/is-american-tolerance-for-political-violence-on-the-rise rising numbers of people on both sides of the political ideological divide believed that violence could be justified if the other party wins the election, or to advance their own political goals.

The role of symbolism in public protest

In the Revolutionary War era, symbolism played a big role in public engagement, such as with burning effigies of tax collectors, the tearing down of the King George III Statue, and the battles over the Liberty Poles that served as rallying symbols for the Sons of Liberty. Symbolism played a role in protests this spring: protestors in Bristol, UK toppled a statue of a slave trader, Edward Colston, and eventually threw it into the nearby river.[8]https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/protesters-throw-slavers-statue-bristol-harbor-make-waves-across-britain-180975060/ Protestors beheaded a Christopher Columbus statue in Boston.[9]https://www.bostonherald.com/2020/06/11/beheading-removal-of-christopher-columbus-statue-adds-to-debate-about-racism/ Controversy around public statues continues — statues whose meaning, really, is only symbolic.

Destruction of symbols sends a message. It can bring people together. And though we are loathe to admit it, it is often fun – maybe that is one reason why destructive acts occur despite the fact that we know better. In our virtual program we conclude with a homework activity, asking participants to symbolically destroy something they would like to destroy, just like those coronavirus pinatas that folks used to beat their frustrations with the disease

https://etc.usf.edu/clipart/5600/5623/ny_stamp_riot_1.htm

John Gilmary Shea, The Story of a Great Nation (New York: Gay Brothers & Company, 1886)after 300, says “page 392”

ClipArt ETC is a part of the Educational Technology Clearinghouse and is produced by the Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida.

We created Civil Unrest For Change as a virtual lesson about the early unrest in NYC leading up to the fight for American Independence, resonating with modern civil unrest. With schools going virtual, students can’t take a field trip to the site of the Battle of Golden Hill. But through our virtual program they can see the site, study historic images, and engage with the big ideas.

Civil Unrest for Change (designed for grades 4-8 but applicable to older grades as well) is available upon request by emailing us at [email protected].

Over the next months, we will be creating additional educational videos, lesson plans, and remote learning opportunities that will tie current events and universal ideas into the Seaport’s mission.

- Do we need to conserve water and other resources? Learn about water use on Wavertree.

- Is the country involved in a trade war? How did Wavertree and ships like her play a role in global trade?

- Is our country struggling with inequality? How did inequality and class structure play out on sailing ships?

Look for these lessons and more in the coming weeks.

FURTHER READING:

The History behind the King George III Statue Meme: Removing monuments of the confederacy is as much about the people calling for change as it is about the statues themselves, by Krystal D’Costa, August 23, 2017; scientificamerican.com

Long Toppled Statue of King George III to Ride Again by David W. Dunlap, Oct 20, 2016, New York Times

Teaching American History With NYPL Digital Collections: Revolutionary New York by Julia Golia, Curator of History, Social Sciences, and Government Information, Stephen A Schwarzman Building, June 11 2020

“The battle for New York : the city at the heart of the American revolution” by Barnet Schecter, 2002.

“Generous enemies : patriots and loyalists in Revolutionary New York” by Judith L. Van Buskirk, published by University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

“Teaching American History With NYPL Digital Collections: Reconstruction” by Julie Golia, Curator of History, Social Sciences, and Government Information, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, April 15, 2020.

“Exploring pre-revolutionary New York. The Ratzer Map” by Brooklyn Historical Society.

References