Discover the Museum’s Flag Collection and How We Care for It

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections and Exhibitions

October 26, 2023

The South Street Seaport Museum has over 600 historic flags from all over the world, with most flags dating from the mid-19th to mid-20th century. The recent additions of new flags to the collection have piqued my interest in sharing with you all a bit more about flags history, highlights from the Museum’s collections, and the preservation needs of flags.

Flags recognizable as such were almost certainly the invention of the ancient peoples of China. Although no extant depictions survive, it is reported that the first banners were carried in processions in front of the leader of the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE).[1]The Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) was among the most culturally significant of the early Chinese dynasties and the longest lasting of any in China’s history, divided into two periods: Western … Continue reading Flags had equal importance in ancient India, being carried on chariots and elephants, and armies from ancient Egypt, Persia, and Babylonia hoisted various flags or standards during battles, or upon the walls of captured cities. Flags were probably transmitted to Europe by the Saracens. The custom of avoiding figures in Islamic art influenced flag design in their greatly simplified appearance.

Ancient flags were considered to connect to spiritual power, but they were also practical, providing visual reference for soldiers engaged in combat. Building on this tradition, Roman legions carried lances with metal eagles mounted atop, and their influence on modern national flags can be seen in the design of many flagpoles, which also bear eagles or other symbols. In Europe the first “national” flags were adopted in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and were subdivided according to their shape and purpose into banners, guidons, pennons, standards, and streamers.

When mariners started crossing the oceans, flags became an important communications tool between ships at sea, and to the shore. Lives depended on correct interpretation of their meaning, especially during warfare. In 1515, it was recorded that the French Navy was the first of the Western navies that prepared and used an extensive signaling system utilizing flags and banners, maintaining an advantage on other countries until the Napoleonic period.

Today, proper use of flags is not just a way to identify vessels and boating organizations, but to give important instructions, make announcements, warn of approaching storms, and mostly to honor and keep alive the naval traditions and seamanship spirit of those sailors that preceded us. Flags have different shapes, colors, and names depending on their function, so let’s first understand some terminology.

Vexillology: the formal study of all aspects of flags.

The term was coined in the late 1950s by Dr. Whitney Smith Jr. (1940–2016), one of the premier scholars on all aspects of the history, symbolism, and significance of flags. The term comes from the Latin vexillum, originally meaning a horizontally-displayed banner of the type used by Roman legions, and the Greek suffix logy indicating “the study of.”

In the course of his professional work, Smith developed standard vocabulary and design definition norms for flags now used worldwide, including vexillography, meaning flag designing, and civil ensign, to identify the flag flown by privately-owned vessels. He also later founded The Flag Research Center, now housed at The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at The University of Texas at Austin.

Before the influence of Smith’s work became felt, flags were generally considered as simply a colorful hobby. When asked why they should be taken more seriously, Smith’s standard reply was “People kill for flags. People die for flags. It is incumbent on us to try to understand how a piece of cloth can incarnate that power.”[2]In memoriam: Whitney Smith” Reproduced with the kind permission of The Flag research Center from The Flag Bulletin #234.

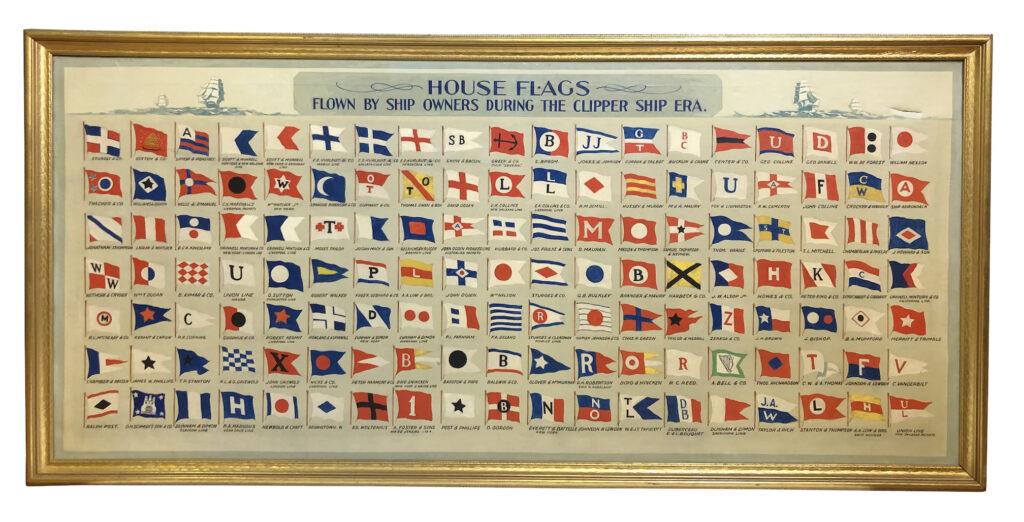

“House Flags Flown By Ship Owners During the Clipper Ship Era” mid-20th century. Oil on canvas. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation, 1991.068.0033

The Seaport Museum’s collection includes:

House Flags: first introduced in the late-18th century, house flags are used to indicate the company a ship belonged to. They enabled shipowners to identify their cargo and passengers as their ship approached the port.

Pennants: flags that are larger at the hoist than at the fly and can be triangular, tapering, or swallow-tailed.

Burgee: triangular or swallow-tailed pennant flags that identify a recreational boating organization. The origin of the word is perhaps from the French dialect bourgeais, meaning shipowner.

Ensigns: national flags displayed on ships and aircraft, often with the special insignia of a branch or unit of the armed forces, such as a badge, emblem, or token of power or authority.

Signal Flags: the most important form of communication at sea, first officially used on October 26, 1871, in Oswego, New York, and still in existence today.

For centuries, flags were the only form of communication between ships at sea, and between ships and the shore. In the 19th century, signaling with special flags developed into a system capable of passing several types of information and relatively elaborate messages. This even became a successful form of communication between crews who didn’t share a common language.

“Frigates Chesapeake and Shannon” 1816. Oil on canvas. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 1991.068.0086

Anyone who wants to find out which flags were used by a particular ship on a particular occasion will usually have to seek the answer in contemporary historical sources. Best practices in this field of documentation include comparing evidence from official ship records supplemented by contemporary narrative sources and visual evidence. However, it is not uncommon to find sources that contradict one and another, and paintings are particularly hard to assess as we have to rely on the attention to details of the artists.

Seaport Museum Archives resources

Part of our jobs here in Collections and Exhibitions Departments is to care and document our flags collections (as well as depictions of flags in other mediums), and research what kind of source material exists to describe, contextualize, and provide points of interpretation.

By researching our flags and artworks, I realized that the history of sea flags is not a cut-and-dry subject, and many historians and authors explain how there are still many problems unsolved and many pictures unexplained. Luckily, the Seaport Museum and many other museums hold books and manuscripts, drawings and photographs, and, overall, a rich body of source material in which discoveries can still be made.

Notable Flags in the Seaport Museum’s Collection

The Seaport Museum’s art collection has grown in many ways over the past 56 years.

A significant portion of the collection was donated or bequeathed by individuals to the Museum, particularly in the 1980s through the early-2000s. But, over the years, the Museum has also bought large parts of its collection from individual collectors, dealers, and the commercial market, developing and expanding upon the founding collections. One of our most significant acquisitions was the purchase of the Fine Arts Collection of the then-defunct Seamen’s Bank for Savings (1829–1989). The Bank was founded by New York merchants and philanthropists aiming to provide the port’s sailors with a safe haven where they and their families could deposit their wages. Another example was the collections of American architect and designer Der Scutt (1924–2010) who assembled one of the most refined collections of ocean liner art, ship models, and ephemera.

Flags were acquired in similar manners from individuals, collectors, or via purchases, and further gifts continue to this day as the Museum is still actively collecting in the 21st century to ensure the collection becomes more inclusive, and better represents New York City’s place in the world today.

Some highlights of our holdings include house flags tied to New York City and New York Harbor maritime industry and sailing operations.

This flag is for Merritt-Chapman & Scott, a renowned marine salvage and wrecking operations firm headquartered in New York, nicknamed “The Black Horse of the Sea.” The chief predecessor company was founded in the 1860s by Capt. Israel John Merritt (1829–1919), but a large number of other firms were merged over the course of the company’s history. In addition to salvage operations, the company got involved in marine construction, acquiring a number of boats, and steam derricks.

“Merritt Chapman & Scott Flag” 20th century. Wool. Museum Purchase 1975.004.0026

The Seaport Museum does not hold many records of the company that ceased operation in the early 1970s, but we have more artifacts documenting their activities including ship models as well as photographs and documentation of their derricks, boats, and diving operations.

This flag belonged to The American Bureau of Shipping (ABS), the first organization chartered in the State of New York in 1862, to certify ship captains. ABS was founded as the American Society of Civil Engineers and today, it verifies that merchant ships and marine structures presented to it comply with rules that the society has established for design, construction, and periodic survey.

“American Bureau of Shipping Flag” 20th century. Wool. Museum Purchase 1975.004.0014

Another particular category of flags in the Museum’s collection is pennants. Narrow pennants of this kind go back several thousand years. They appear in ancient Egyptian art and were flown from ships’ mastheads and yardarms from at least the Middle Ages; they appear in Medieval manuscript illustrations and Renaissance paintings. Professional national navies began to take form late in the 17th century and, as a standard naval practice, adopted long, narrow pennants to be flown by their ships at the main mast head to distinguish themselves from merchant ships.

“Naval Ships New York Harbor” 1886. Oil on canvas. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 1991.068.0168

Until the early years of the 19th century, flags and pennants were quite large, as is seen in period pictures of naval ships. By 1870, for example, the largest Navy pennant had a 0.52-foot hoist (the maximum width) and a 70-foot length, called the fly; the biggest ensign at that time measured 19 by 36 feet. As warships took on distinctive forms and could no longer be easily mistaken for merchantmen, flags and pennants continued to be flown but began to shrink to a fraction of their earlier size. This process was accelerated by the proliferation of electronic antennas through the 20th century.

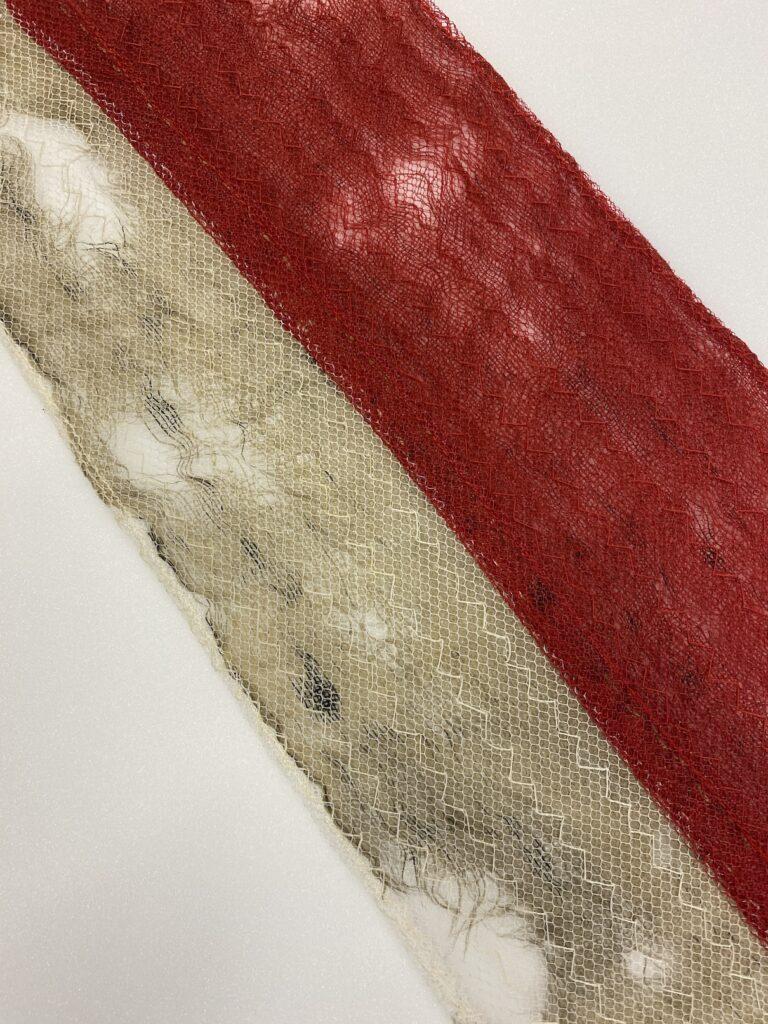

All images: “Battle Pennant from US Privateer Paul Jones” 1813. Cotton. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.072.0168

This red cotton woven pennant is a battle pennant from the US Privateer Paul Jones. It was bequeathed to the Seamen’s Bank for Savings by the late Archibald G. Thacher, former trustee of the Bank and later senior member of Thacher, Proffitt, Prizer, Crawley & Wood. Thacher’s great-great uncle was Archibald Taylor, Commander of the Paul Jones during the War of 1812.

The pennant is 9 inches wide at the biggest width, and 49 feet long. The pennant was restored in 1975 by the Bank by encapsulating it into an additional fabric sleeve for the entire length of the object.

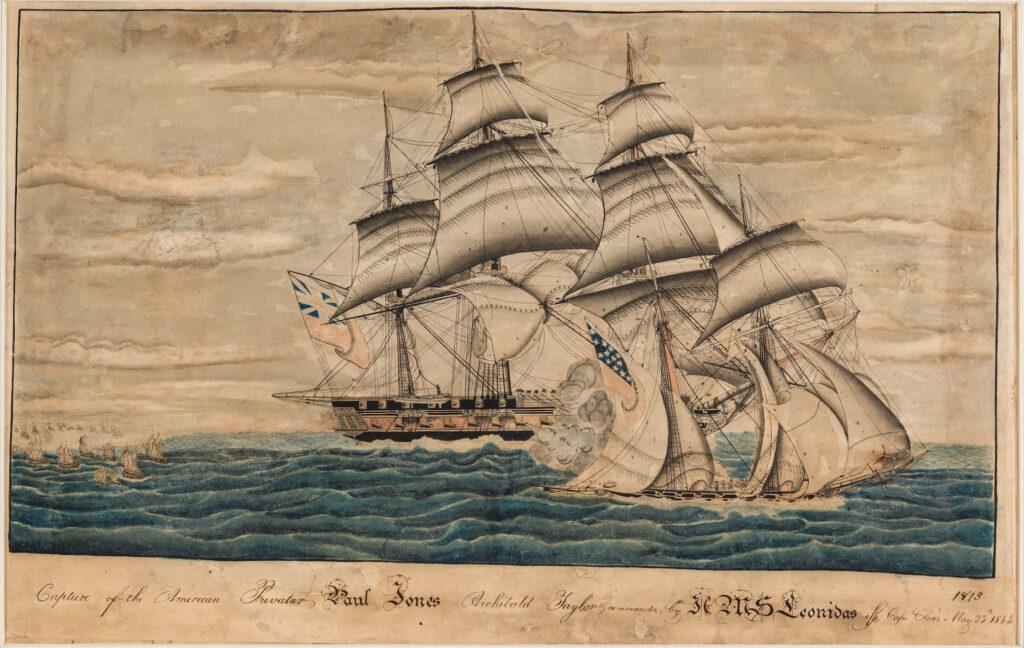

Many of the heroes and much of the glamor associated with adventure on high seas in the late-18th century came from privateering, a more respectable piracy that was widely used in navy strategy. During the Revolutionary War privateers—privately owned ships that were authorized by their countries’ government to attack and capture enemy vessels—helped America win Independence.

“Capture of the American Privateer Paul Jones” 1813. Paper, watercolor. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.071.0001

A particular type of pennant is a burgee.

This burgee flag from USS Amphitrite belongs to the Harry Handly Caldwell Collection, consisting of books, documents, artifacts, and letters belonging to Harry Handly Caldwell (1873–1939) relating to his career in the United States Navy.

The collection includes seven bound books of watercolors from 1918 depicting World War I ships painted in dazzle camouflage, three parcels of letters to his mother from 1887–1908, naval correspondence and related ephemera dated 1917–1934, several related newspaper clippings and telegrams, as well as photographic prints.

“USS Amphitrite Burgee Flag” early 20th century. Wool, rope. Gift of Harry H. Caldwell Jr. 1994.012.0001

Caldwell resigned from the Navy in 1909, but remained active in the reserves. After resigning, he joined the motion picture business and, in 1916, became the vice president of the C.L. Chester Company, producing travel documentaries. Caldwell’s motion picture career was interrupted when the United States entered World War I. On May 10, 1917, he returned to duty in the Fleet Naval Reserve, commanding USS Amphitrite, the guard ship of New York Harbor. He was in charge of the submarine net protecting the Harbor and all entering vessels had to report to him. He was promoted to commander on November 14, 1919, and would officially retire from the United States Navy on November 19, 1935.

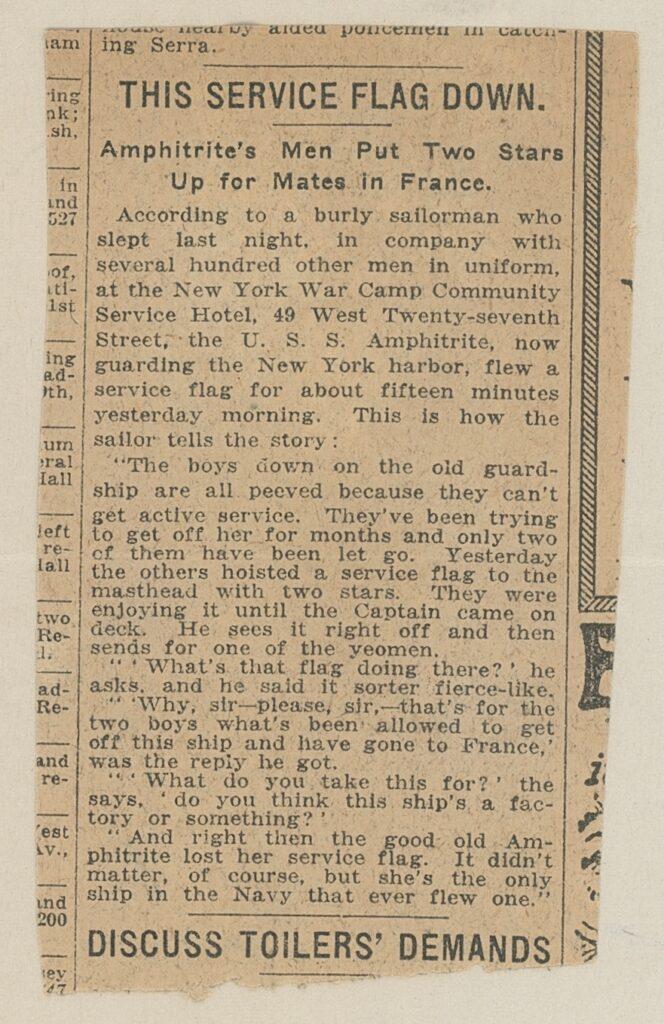

Left: [Clipping describing USS Amphitrite flying service flag with envelope]. September 19, 1918. Gift of the Caldwell Family 2023.004.0038

Right: [Portrait of H.H. Caldwell standing on the deck of USS Amphitrite with his dog Fong] ca. 1917-1919. Gift of the Caldwell Family 2023.005.0012

Because of this extensive collection, we know that on September 19, 1918, an article was published, and later on collected by Caldwell as a newspaper clipping, mentioning Caldwell’s insistence that his crew take down their active service flag, which they were only able to fly for fifteen minutes. According to the clipping itself, the crew of Amphitrite had all been vying to be moved from the naval reserves to active duty, (which Caldwell himself requested in his correspondence.) Only two of them were given the opportunity for active duty in France, and so the crew who remained behind raised the flag to honor them without Caldwell’s approval.

Lastly, let’s briefly talk about signal flags.

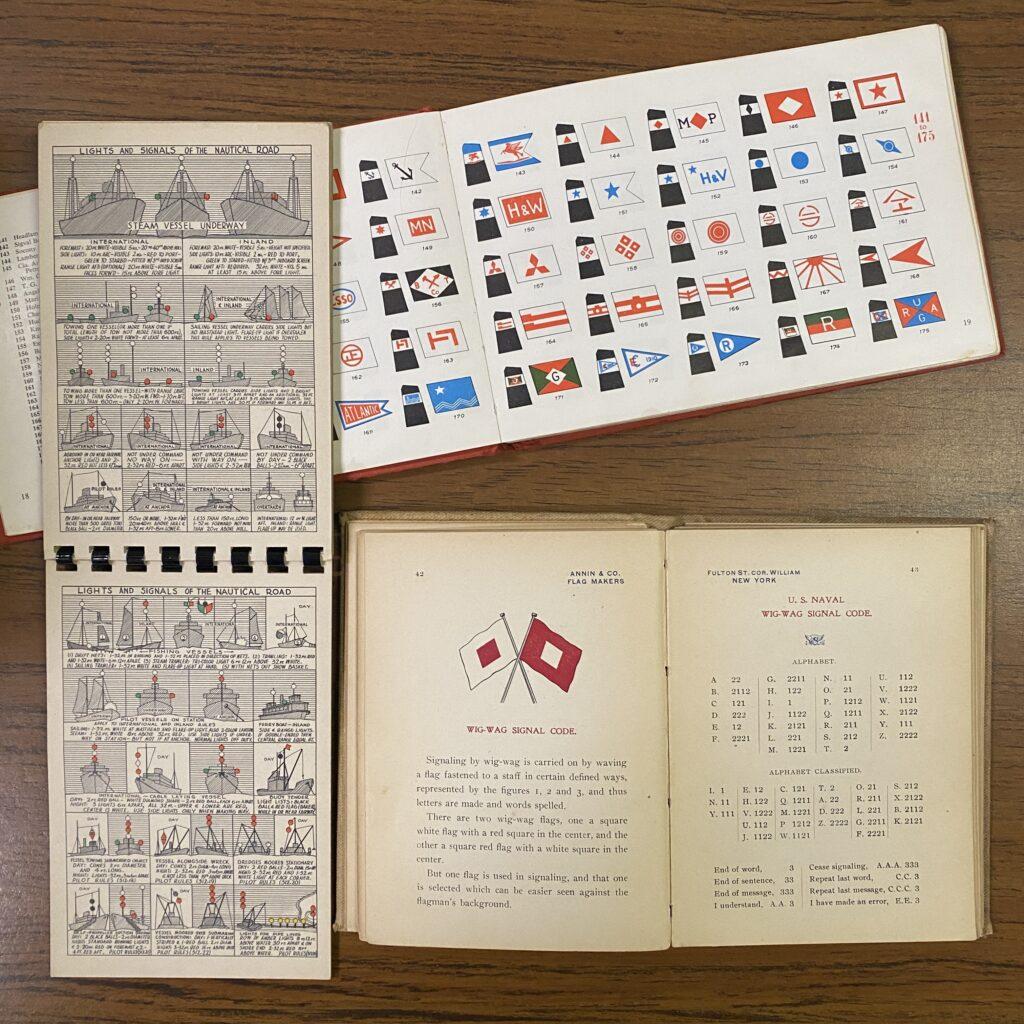

Numerical naval signal codes were introduced at the end of the 18th century, replacing the simpler system set out in various editions of Sailing and Fighting Instructions.[3]The earliest is a printed copy of 1673 issued to James Duke of York (1633–1701). Subsequent sets show the development which took place up to the Seven Years War. From 1756 onwards additional and … Continue reading In the new codes, a series of different flags was numbered one to ten, and hoisted in groups of one to four flags. The number the flags hoisted corresponded to a numbered order, word, or sentence in the codebook.

In 1817, Royal Navy Captain Frederick Marryat (1792–1848) introduced a similar code for the merchant service, which was the first general system of signaling for merchant vessels. Several systems of signal codes succeeded each other, all ultimately superseded by the first International Code of Signals, including 40 flags for the letters in the alphabet, numerals 0–9, and four alternates. This first Code was drafted in 1855 by a Committee set up by the British Board of Trade. It contained 70,000 signals using 18 flags and was published by the British Board of Trade in 1857 in two parts; the first containing universal and international signals and the second British signals only. The book was adopted by most seafaring nations.

The Code passed many revisions, toward the end of the 19th century, but the 1897 edition did not stand the test of World War I. Revisions keep happening, and the International Code has become the standard for all major maritime nations.[4]INTERNATIONAL CODE OF SIGNALS FOR VISUAL, SOUND, AND RADIO COMMUNICATIONS. UNITED STATES EDITION. 1969 Edition (Revised 2020)

Training on the code could have happened in many ways. Below, you see three objects from the Museum’s collection used during training and sailing.

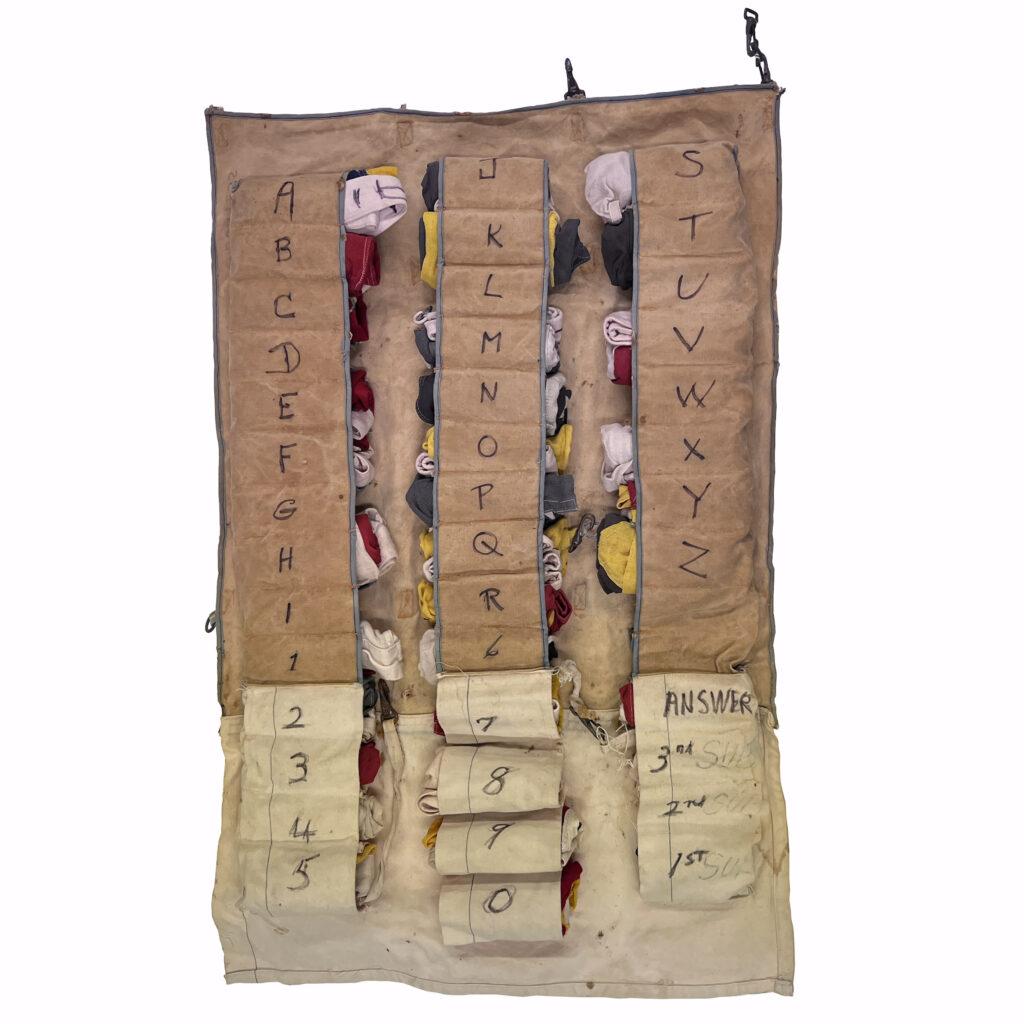

Left: “Signal Flag Training Kit” 20th century. Gift of Boucher-Lewis Precision Models 1975.062.0002

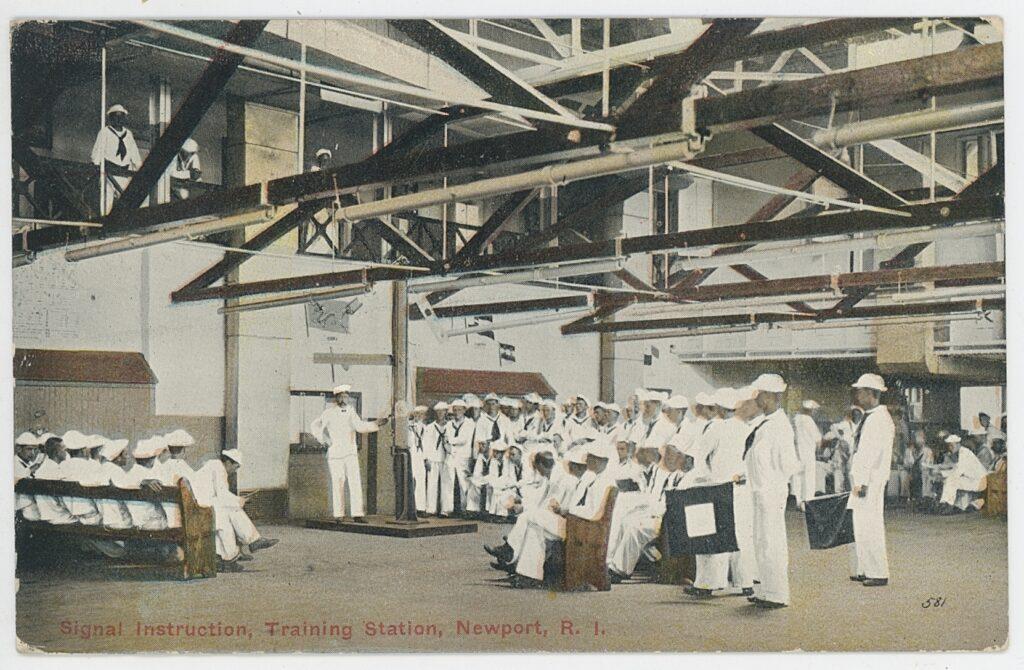

Right: “Signal Instruction, Training Station, Newport, R.I.” August 8, 1913 (postmark date). Gift of Wendell Lorang 2005.051.0336

This Training Kit was donated by the manufacturing company Boucher-Lewis, which has an incredible history in advancing training for the US Navy. The firm was founded by Mr. Horace E. Boucher, a French naval architect employed by the United States Navy. In 1905, he made the observation that scale models, although in common use throughout Europe, were practically unknown in the United States. After leaving the Government service, he established his own company and later partnership with Patton Lewis in New York City. During World War II and into the decades of the 1950s and 1960s the heavy demand for naval and commercial vessels resulted in record orders for models. Many still remain on display in maritime museums, yacht clubs, and Government offices.

The postcard instead depicts sailors in signal training in Newport, Rhode Island. In the 1880s the Navy began offering shore-based instruction, rather than simply learning on the job as they had done previously. The Training Station in Newport Rhode Island was one such instructional facility. By 1930, there was a naval hospital and college at the site. Today, called the Naval Station Newport, it remains one of the Navy’s premier sites for training. This image also possibly depicts racial segregation, as black sailors are following the training on the upper balcony, while the white sailors are on the main floor.

This Signal Flag kit comes from the schooner Countess, a Nova Scotia built vessel, based on the fishing schooner Bluenose.

The vessel was owned by Museum trustee Jack R. Aron during the 1930’s, and often sailed in the Newport-Bermuda Race.

Later, she was transferred to the US Coast Guard at the beginning of World War II for offshore submarine patrol off Long Island. It is fairly easy to unfurl the individual signal flags and keep it as neat as it could be.

“Signal Flag belonging to schooner Countess” ca. 1934. Canvas, cotton, metal, ink. Gift of Peter A. Aron 1999.014.0002

How To Take Care of Flags

Artifacts have unique preservation and conservation needs based upon their past history, the materials used in their construction, and the purpose of their preservation—research or display. Flags are for the most part made of organic materials, which are damaged by exposure to light, air, high temperatures, elevated levels of moisture, and chemical pollutants.

Flags usually have seen outdoor use, and their fibers are already damaged from exposure to sunlight, so extra care needs to be taken to ensure no further damage is done, particularly in their lighting exposures and environmental controls.

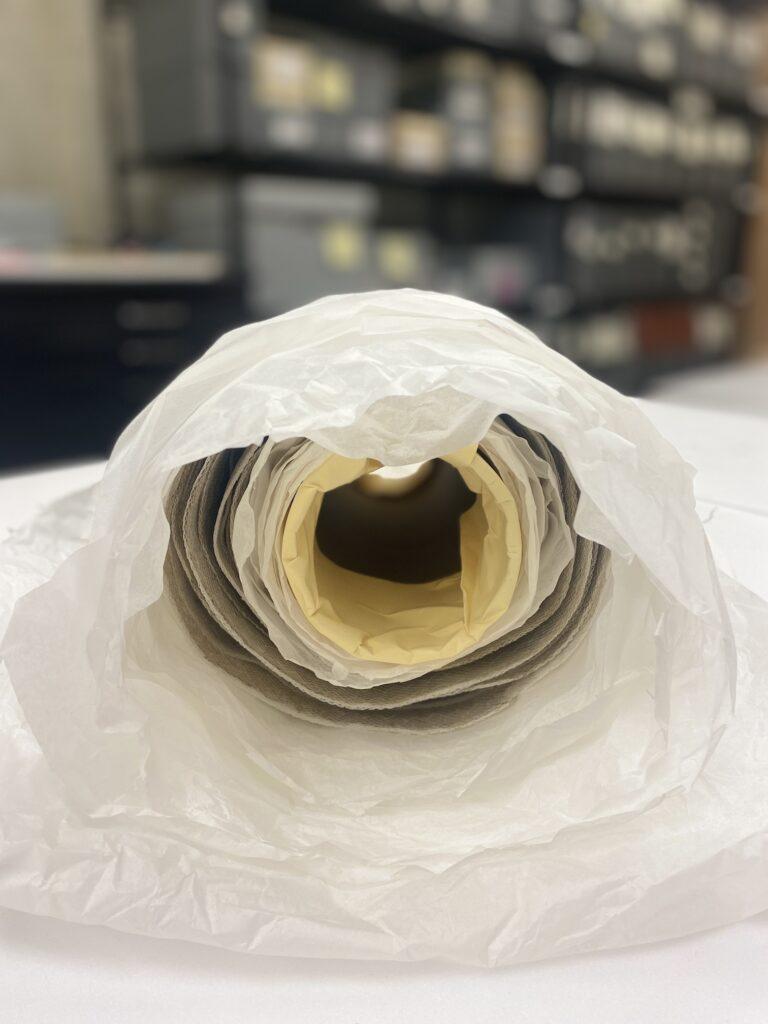

The presence of oxygen is necessary for many chemical deterioration processes to continue. When possible, framing flags is advisable to limit their contact with the oxygen in the air. For long term storage, flat storage is ideal because it minimizes damaging folds, but we know that space constraints often limit the size of the boxes and storage location.

If you are looking to re-home textiles, keep in mind that many materials for household storage will actually damage the textile—including regular tissue paper, cardboard, and wood. Best practice preservation requires acid-free storage materials.

In the image here on the left, you can see how we store our items between acid-free tissue, inside acid-free boxes.

Wool, linen, and unglazed cotton are usually the best candidates for folded storage, ideally along seam lines. Wool is more resistant to fold and crease.

If we need to stack the textiles for storage and we cannot create shelves or supports, we place the heavy wool on the bottom and the lighter, more fragile linen or silk on top.

When handling textile we wear gloves because the materials can easily pick up soil and oils. You also want to make sure to have a work surface that is large enough to support your piece.

A considerable concern to keep in mind when storing flags and vintage textile is moisture, as different types of fibers react differently. Many flags use multiple fibers, and exposure to high levels of moisture can cause stresses that will damage the fibers, including mold. Mildew is a more common problem for cellulosic materials such as cotton and linen, it can also grow on soils and greases found on wool. And so, storage at relative humidity levels should be below 65%.

Lastly, one should consider the level of urban pollution sources, such as car exhaust, as they can be very damaging to textiles, fibers, and dyes. Textiles you wish to preserve should not be displayed by open windows in urban environments.

Good housekeeping procedures will prevent damage or at least stop damage before it becomes more serious. Best practices include, inspections at least every six months, vacuuming off loose debris before it becomes embedded, and once a year, refolding your textiles.

Additional Reading and Resources

“Flags; some account of their history and uses” by Andrew Macgeorge. London Blackie, 1881.

“Notes on the Early Development of the Designs in Marine Signal Flags” by Howard M. Chapin. US Naval Institute, November 1927 Proceedings Vol. 53/11/297.

“Flags Through the Ages and Across the World” by Whitney Smith Jr., 1975.

“The Flag Book of the United States” by Whitney Smith Jr., 1975.

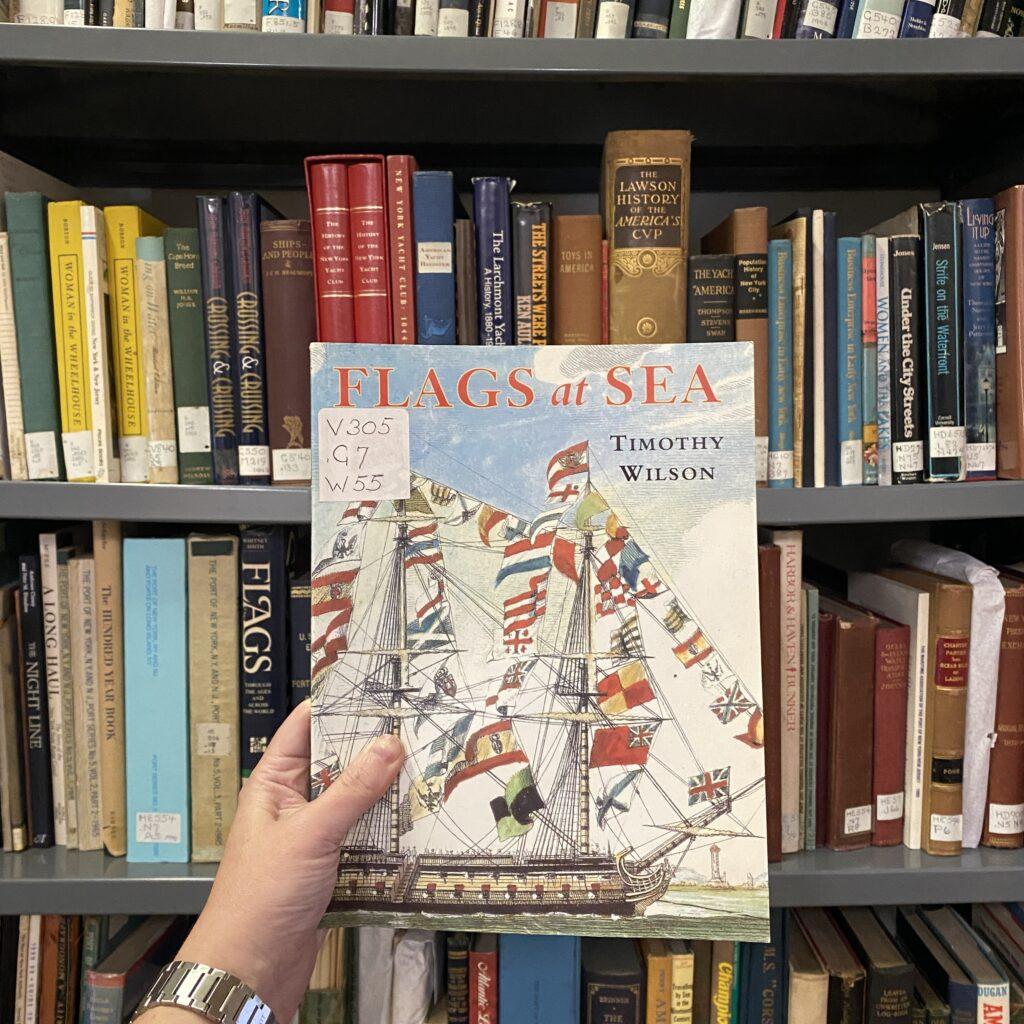

“Flags at Sea: a Guide to the Flags Flown at Sea by the British and Some Foreign Ships, from the 16th Century to the Present Day” by Timothy Wilson, 1986.

“You Asked, We Answer: Why can’t I take a picture of the Star-Spangled Banner?” By Megan Smith. National Museum of American History. May 27, 2010.

“Where Do Flags Come From?” by Ben Nadler. The Atlantic. June 14, 2016.

“Huge flag captured from French battle ship by Admiral Lord Nelson to go on display for first time in 100 years” by Rhian Lubin, February 15, 2017.

“An Introduction to the True Colours Flag Project” Museum of the American Revolution. April 2021.

Acquisition Guidelines

The Seaport Museum’s Collection Management Policy, last revised in May of 2024, outlines the scope of the Museum’s collection, explains how the museum grows, cares for and makes collections available to the public, and clearly defines the roles of the parties responsible for managing these artifacts.

References

| ↑1 | The Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) was among the most culturally significant of the early Chinese dynasties and the longest lasting of any in China’s history, divided into two periods: Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (771–256 BCE). It followed the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), and preceded the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE, pronounced “chin”) which gave China its. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In memoriam: Whitney Smith” Reproduced with the kind permission of The Flag research Center from The Flag Bulletin #234. |

| ↑3 | The earliest is a printed copy of 1673 issued to James Duke of York (1633–1701). Subsequent sets show the development which took place up to the Seven Years War. From 1756 onwards additional and supplementary instructions became more numerous. See more on the online collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

| ↑4 | INTERNATIONAL CODE OF SIGNALS FOR VISUAL, SOUND, AND RADIO COMMUNICATIONS. UNITED STATES EDITION. 1969 Edition (Revised 2020) |