New York arose from the sea. The city’s identity today as a global cultural and financial capital is rooted in its origins as a seaport. For four centuries, the port of New York has connected to the world through the exchange of goods, ideas, languages, and cultures. Indigenous Lenape people were the first stewards of the waterways, creating trade routes connecting Manahatta to the sea. In the 17th-century European colonists, enslaved Africans, and migrants built on this foundation to give birth to a restless and ambitious city. Later waves of immigration, would grow a world capital formed by its oceanic links to the world

New York City owes its rise as a global center of commerce and culture to its origins as a seaport. For four centuries, the Port of New York has been central to the country’s growth, becoming the busiest harbor in the world by the end of the Civil War, fueling finance, manufacturing, and publishing, and establishing the city as a gateway for millions of immigrants. But by the middle of the 20th century, with waning maritime and commercial activity, the South Street Seaport district had fallen into decline and faced the prospect of demolition. Preservationists stepped in and, in 1967, established the South Street Seaport Museum, through which they purchased abandoned buildings and, together with the city, designated the area a historic district.

South Street

The stretch of land along the East River was recognized as an ideal spot for shipping enterprises in the 17th century when the Dutch West India company established New Amsterdam in 1624. New York’s natural harbor allowed New Yorkers to develop maritime trading connections across America and the globe, which transformed New York into a global center of commerce, finance, manufacturing, communication, and culture. As the port fostered the city’s dynamic economic and cultural energy, that energy attracted the talent and skill of people from around the world, making New York the most ethnically diverse place on the planet.

Before the shoreline we see today was created with man-made infill, Manhattan had a much narrower and more irregular shape. The southern tip of the island, known as Kapsee, was a rocky point jutting out into the harbor, forming a small cove that was possibly used as a canoe landing by Indigenous communities. As New York City expanded during the late 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, the City of New York and private owners gradually modified the East River shoreline with wharves, docks, and slips. In response to pressure for new commercial real estate, and in order to address the poor conditions of existing waterfront infrastructure, the shoreline was built increasingly further into the East River. This shoreline was characterized by an almost-continuous network of slips that allowed ships to dock between wharves.

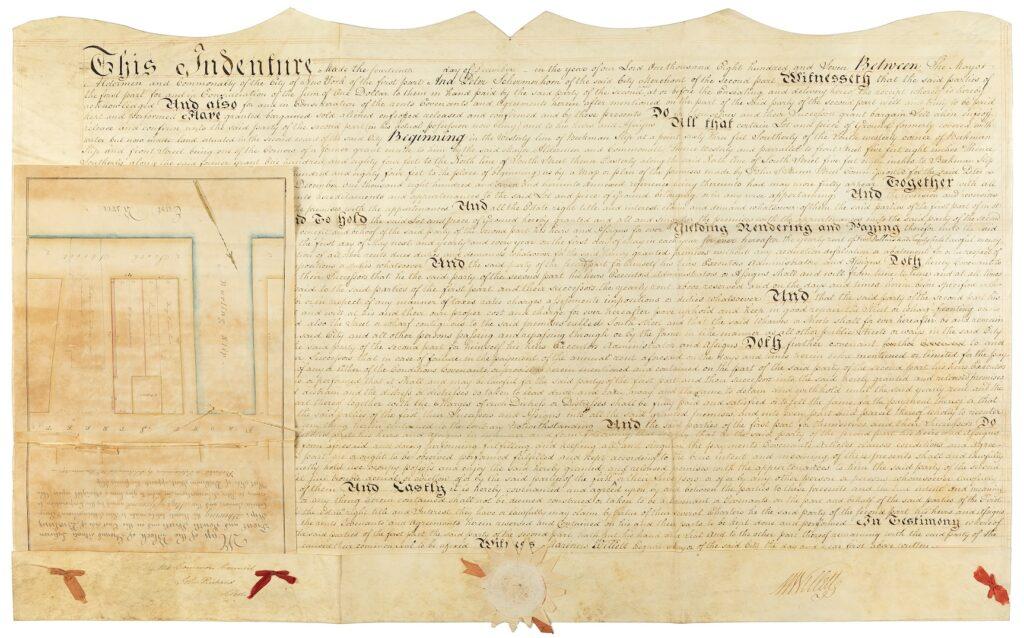

South Street, the right-of-way fronting the East River, was built on landfill between 1798 and about 1810, and sits three blocks further into the river than the original waterfront. The seaport is built on “man-made land” created through a process of selling water lots to wealthy merchants, who were required to fill in the lot at their own expense to create an extension of the island itself.

Through this arrangement, the colony generated income and gained new land, and merchants were able to build wharves and slips to accommodate ships. They could also use the infilled land to build adjacent counting-houses and warehouses to support the transport of their goods.

This official document is an example of the land grant agreements stipulated by the City of New York and merchants like Peter Schermerhorn (1749–1826).

“Peter Schermerhorn Land Grant” 1807. Museum Purchase with funds by Anne E. Beaumont, 2024.003.A-.B

In 1813, Beekman Slip became the Manhattan terminal for the Fulton Ferry, which traveled regularly between Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. In 1818, New York merchants right here on South Street pioneered the idea of running ships on set schedules over fixed routes. Prior to this innovation, ships left port only when full, which frequently delayed goods and deterred many travelers. The radical idea of sailing on time, whether “full or not full,” revolutionized coastal and international trade, attracted more commerce to New York, and, most vitally, made transatlantic travel more reliable and appealing to a wider range of people than ever before.

“The city side of the East River,” wrote an English visitor in 1846, “[is] covered, as far as the eye can catch, with a forest of masts and rigging, as dense and tangled in appearance as a cedar swamp.”[1]“Markets: The Fulton Fish Market” by Kathryn Graddy. Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, Spring 2006, pp. 207-208. At the time the neighborhood started to fill up with businesses related to the ships docked nearby: sailmakers, wood carvers, ship chandleries.

Until the Civil War (1861–1865), South Street was the city’s principal seaport, where ships involved in both international and domestic trade tied up directly across the street from warehouses, markets, hotels, and tradesmen’s shops. The port of New York, centered on South Street, received more than 4,000 vessels from foreign ports alone in 1860.

John Stobart (1929–2023), “New York Maiden Lane by Gaslight from a Ship at Pier 19 in 1882” 1985. Gift dedicated to the memory of our father Erwin Bieber, 2023.003

Beginning in the mid-19th century, emerging changes in ships’ docking and ship technology had a profound effect on the South Street Seaport and its port activities. Whereas the East River’s waters had, up to this point, been able to accommodate sailing vessels and small steamships of the time, they could not accommodate new, larger crowds and steamships.

South Street had also been welcoming immigrants from all over the world for decades, and as the number of new arrivals continued to rise exponentially—and as new immigrants were increasingly taken advantage of at the docks—New York’s government stepped in to establish some order. Thus, the old leisure palace of Castle Garden was refurbished into the first official Emigrant Landing Depot in the nation.

On August 3, 1855, Castle Garden opened its doors to immigrants for processing, health examinations, and to provide information related to potential further travel[2] The governments of New York City and New York State collaborated to collect detailed records of the over 8 million passengers who entered America through Castle Garden. Unfortunately, these … Continue reading. And between 1855 and 1890, two out of every three immigrants who came to America were processed at Castle Garden.

By 1870, steamships carried nine out of ten ocean-going passengers, and the Hudson River became New York’s main port location following the transition of maritime activities from the East River seaport to the West Side of the island[3]In 1847, a pier for larger vessels opened on the west side of Manhattan, in the deeper Hudson River, and the City of New York authorized street-level railroad tracks down Manhattan’s West Side, … Continue reading. Luxury services for a small number of wealthy and business travelers made these ocean liners famous, and indelibly linked New York to the power and prestige of the world’s largest and finest ships. Later, many called this area “Manhattan’s Luxury Liner Row,” elevating it in a way to a new New York City landmark[4]“Manhattan’s Luxury Liner Row” by William H. Miller, published on Power Ships, Spring 2020, pp. 10-15..

Printing History

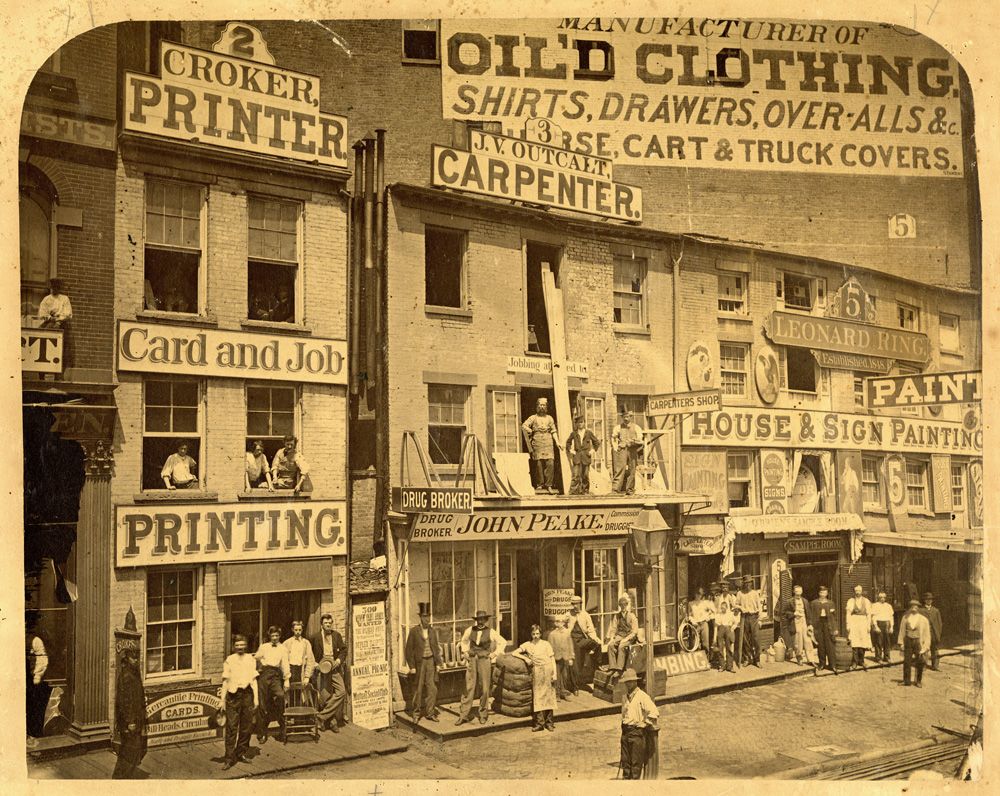

Printing offices flourished in Lower Manhattan. Like every port across the globe, New York developed an entire commercial ecosystem to support trade, and all trade required printed materials. As chandlers, hoteliers, shippers, financiers, and insurers multiplied, demand for printed goods increased, and a new appetite for printed advertisements, stationery, and financial documents birthed a printing industry of its own: job printing.

As New York grew into the trading and financial center of the United States, the number of printers, press makers, paper suppliers, and type founders in the city grew.

When the warehouses of Schermerhorn Row were completed in 1812, the city had fewer than 200 printers. By 1895, when the Museum’s 1885 cargo ship Wavertree called at New York, there were more than 8,000 printers, working out of more than 700 printing offices.

From one-man, single-press operations in basements, to multi-story printing plants that employed hundreds of journeymen, the printing industry generated a flurry of materials that blanketed the piers and counting houses of South Street in paper: from bills and bonds, certificates and circulars, to tickets and timetables.

“Henry Croker Jr.’s job-printing office on Lower Hudson Street” ca. 1865. Photograph by Marcus Ormsbee (active 1840s-1860s) Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society no. 16930

Inside the Printing Office

As speed became central to commerce in the seaport, working in a printing office could be hectic. Ships raced to make the fastest passage around Cape Horn, and prospectors rushed westward with dreams of golden fortunes. Competition for business was fierce, and printers were motivated to keep up with demand to ensure their survival.

In small shops, a master printer would often hire journeymen to increase production. Journeymen would set type, run the presses, and do odd jobs, perhaps with the help of apprentices. If the size of a printing office allowed, roles were specialized for more efficiency. Some journeymen would set, or compose, the type, while others would prepare the type for printing and run the presses.

It was often only in the largest publishing and newspaper offices, where dozens of type compositors were employed, that a woman could hope to find a foothold in the printing trade. Women were considered less capable of the variety of tasks required by job printing, and it was unusual to find one of them working as a compositor in any job-printing office. Hired because they could be paid, on average, three-quarters of a man’s wage, women fell out of favor as employees after successful unionization equalized their pay. One account estimates that, by 1894, there were only about 200 women compositors in New York.

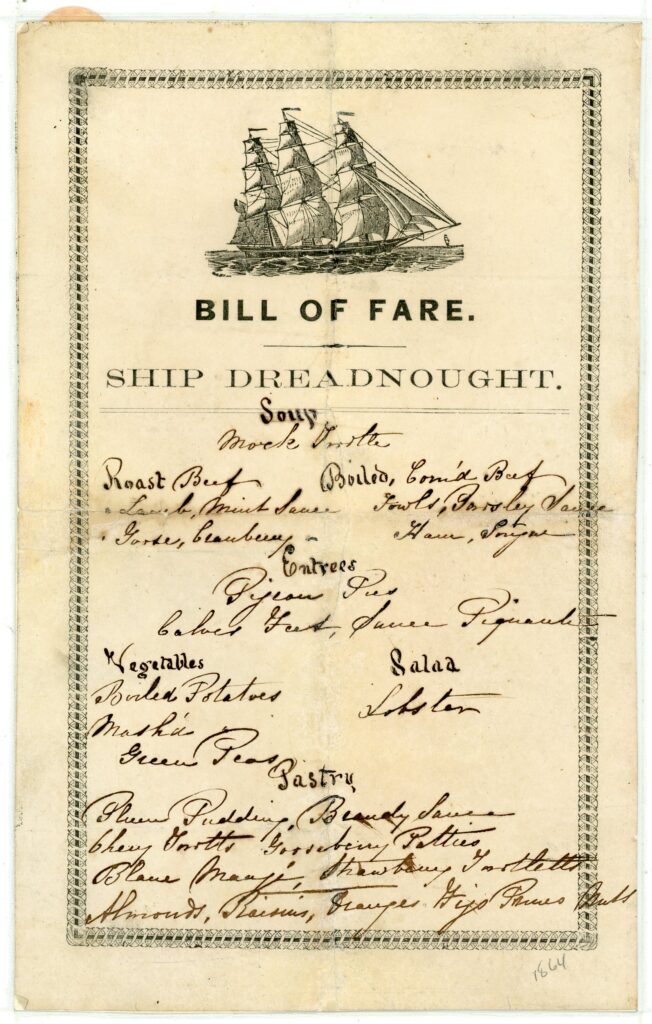

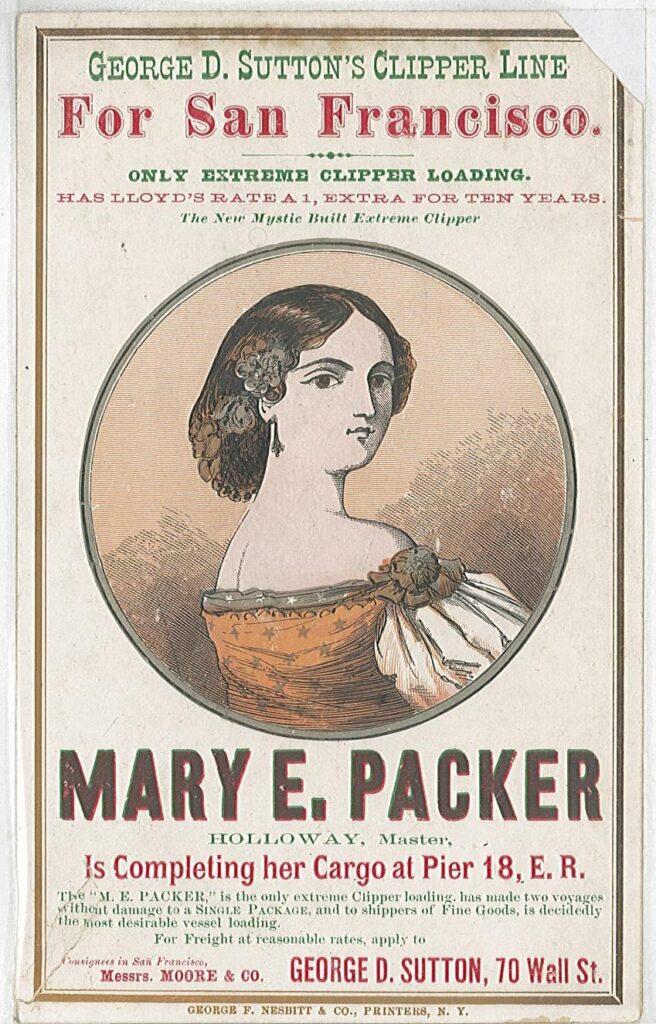

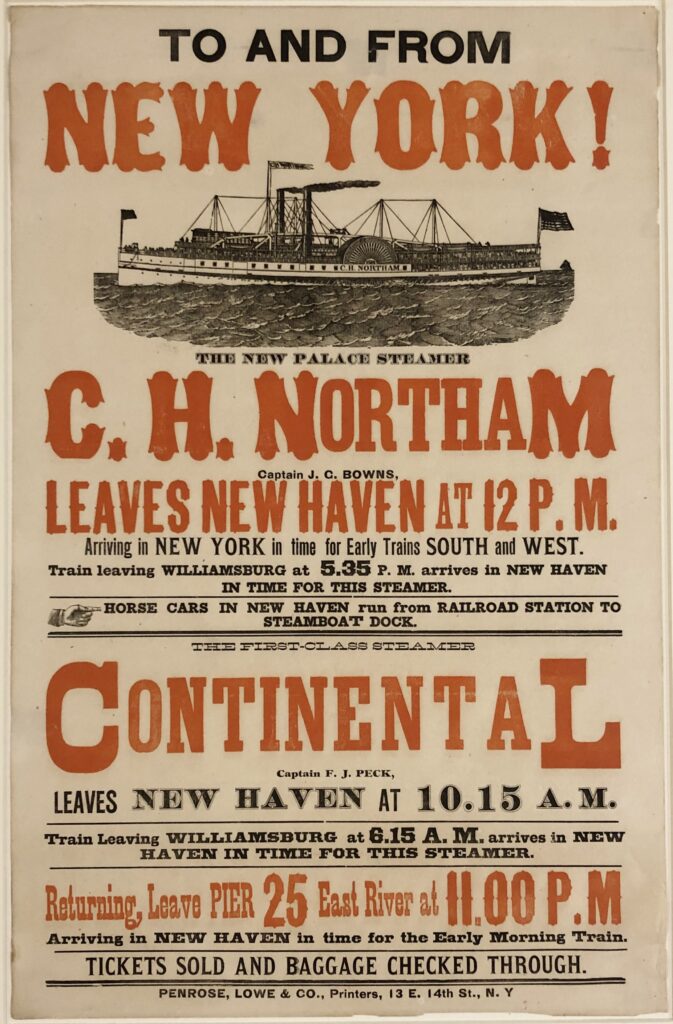

Job printers produced the broadsides that advertised voyages to far-off lands and the invoices for the cargo they delivered. They printed the clipper cards, trade cards, and handbills that advertised goods for sale and the packaging that adorned them. They made the deposit slips that consolidated profits in banks, and the stock certificates that could make that wealth a public investment. The printed items shown here are the very history of the business of the port of New York.

Left: Clipper Ship Dreadnought, Bill of Fare, ca. 1864. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 1991.070.0261

Center: “Mary E. Packer Clipper Card” October 1868. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation, 1991.070.0531

Right: [Broadside advertising steamer C.H. Northam], ca. 1875. Printed by Penrose, Lowe & Co., 13 East 14th Street New York. Gift of Peter Stanley, South Street Seaport Museum 1977.014

Bowne & Co. as a Job Printer

As New York City grew into a center of world trade, Bowne & Co., Stationers, established in the fertile ground that was the 18th-century port of New York, reaped the benefits. What began in 1775 as a small offering of dry goods and stationery became a successful job-printing business, specializing in documents for the expanding banking industry: promissory notes, prospectuses, annual reports, and stock certificates. Through the centuries, Bowne & Co. rose as one of the predominant financial printers in New York.

Celebrating their bicentennial in 1975, Bowne & Co. memorialized their legacy as job printers by opening a storefront in New York’s first neighborhood. Partnering with the South Street Seaport Museum, the Bowne & Co., Stationers and Printing Office function as both museum installations and active businesses. Visitors today can engage with the Museum’s historic printing presses, types, and printing equipment to print modern-day jobs, attend hands-on workshops, and shop for gifts and ephemera. Through preservation efforts and gentle use by our professional printing staff, we are proud to keep the tools and techniques of 19th-century job printing alive. New York’s oldest operating business under the same name since 1775, Bowne & Co. now preserves the arts and skills of letterpress printing.

The Fulton Fish Market

The Fulton Fish Market operated on Fulton and South Streets for more than 180 years. From 1822 to 2005, fishmongers were an extension of the neighborhood. In 2005 the market moved from the South Street Seaport to Hunts Point in the South Bronx. The Fulton Fish Market–now called The New Fulton Fish Market–is one of the world’s largest fish markets, second in size only to Tsukiji, the famous fish market in Tokyo, Japan.

The Fulton Market was historically located in lower Manhattan, near the Brooklyn Bridge, just a few blocks from Wall Street. When it first opened to the public, it was one building, located on South Street, between Fulton and Beekman Street. The stalls sold meat, fish, and other food.

John Pintard, the merchant who was also the founder of the New-York Historical Society, called the Fulton Market “an elegant, quadrangular structure, superior in accommodation perhaps to any thing of the kind, probably even in Europe.” He also noted the “abundant display of every variety of meats, fish and game, exceeding anything I have witnessed in this city.”[5]John Pintard Papers1750-1925 (bulk 1770-1890). Shelby White and Leon Levy Digital Library, Call No. MS 490.

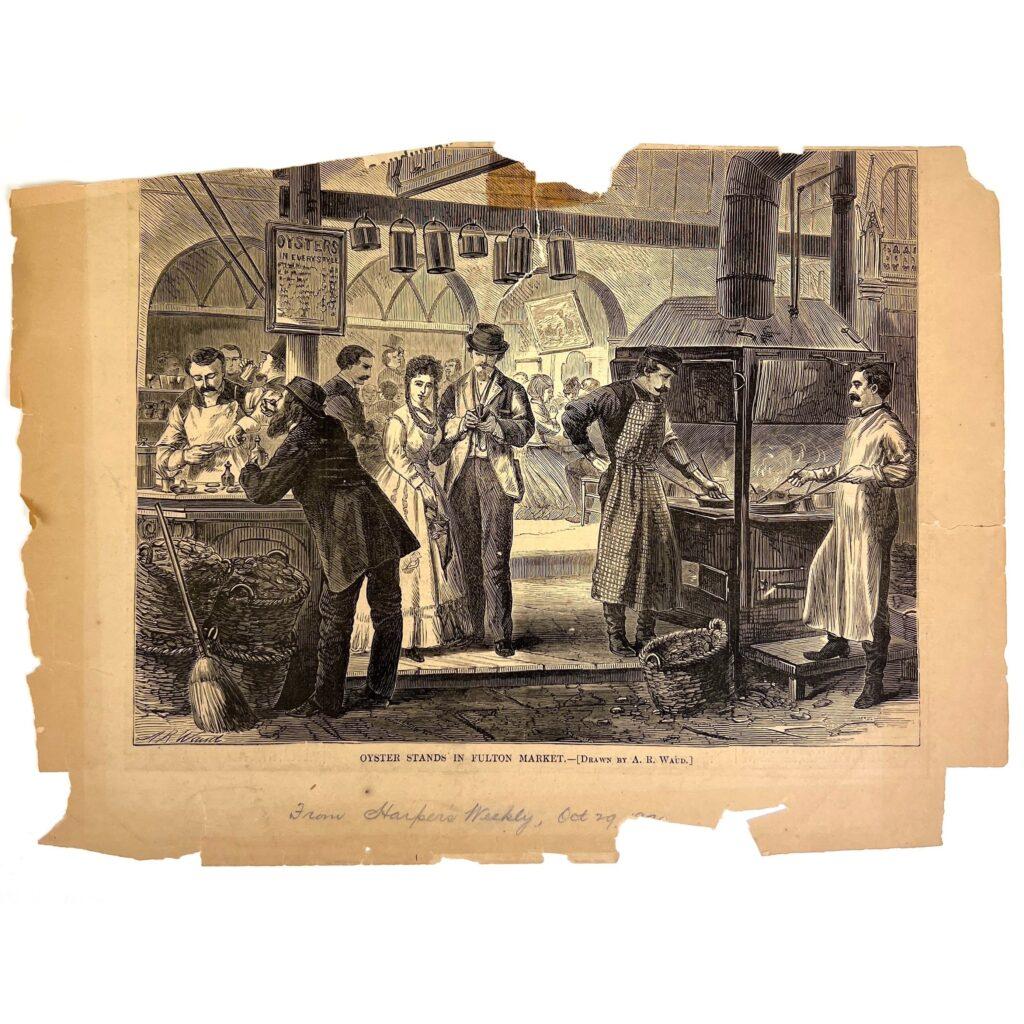

The space underneath the building housed mostly salons that specialize in selling oysters. But just ten years later many butchers vacated the building because they couldn’t pay their rent, and the building was reorganized to make room for a special section designated to fish.

“Oyster Stands in Fulton Market” October 29, 1870. Gift of Joe Cantalupo, 1974.056

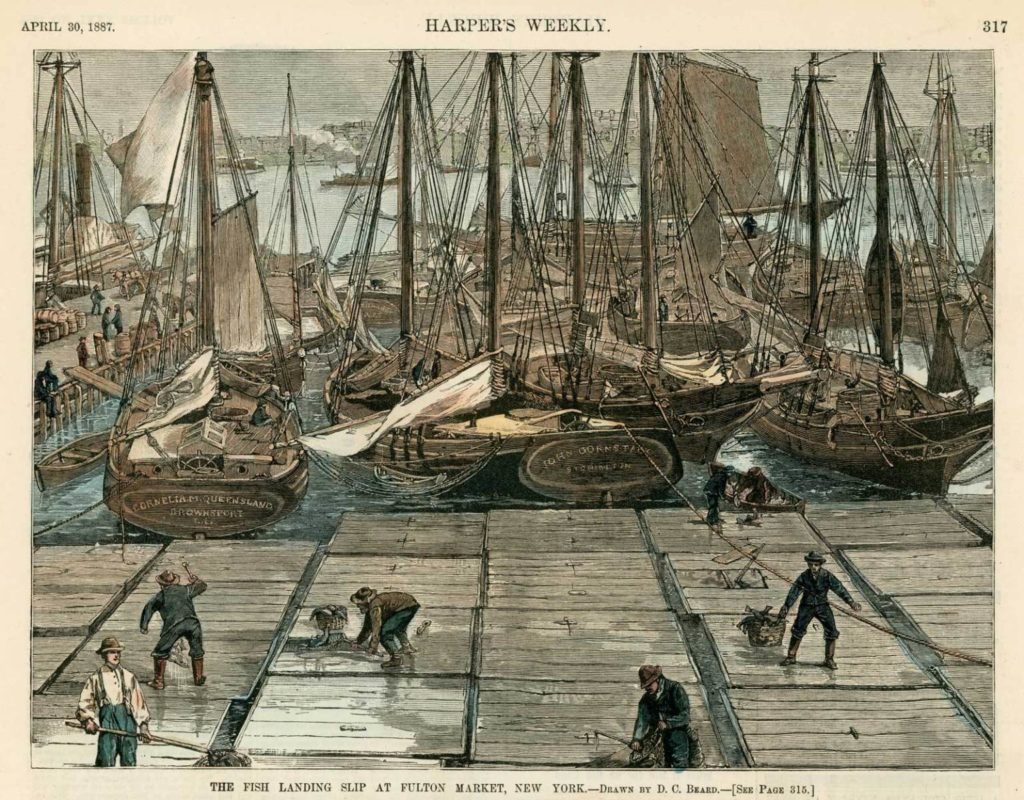

By 1831, the fish business at Fulton Market had become large enough that many fishing merchants moved to a new building on the East River, closer to the fishing boats that docked there daily, between what are Piers 17 and 18 today.

This engraving, published in Harper’s Weekly in 1887, shows us a busy South Street slip with fishing schooners and fishmongers working around crates of fish.

Historically, fish made its way to the port of New York by boat, arriving at the market around midnight. The day’s sales and trades were completed by about 9am. Afterwards, fishes were placed into trucks and gradually dispersed into the city.

“The Fish Landing Slip at Fulton Market, New York” April 30, 1887. Museum Purchase, 2002.014.0004

Visitors of the Fulton Market often wrote in detail about the variety of products available there. This is just a piece of one of the many descriptions from the Evening Mirror, published in 1850:

“There were Valparaiso pumpkins, manna apples from Cuba, peaches from Delaware, lobster from the coast of Maine, milk from Goshen, chicken from Bucks county, Pennsylvania […] mutton from Vermont, adn cheese from the region of St. Lawrence.”[/fn]The Literary World 184, August 10, 1850, p. 116.[/fn]

In 1869 the largest fish sellers organized the Fulton Market Fishmongers Association in order to pool their money and lease land from the city on the waterfront on South Street, between Beekman and Fulton Streets. On that land, they constructed a new building specifically designed for their wholesale operations, which opened the same year.

The structure was almost totally destroyed by fire less than ten years later in November 1878[6]The New York Times, Nov. 18, 1878., but it was quickly rebuilt. A third version of the market building was moved northward across Pier 18, close to the site occupied today by the modern Tin Building, which kept the name from the Tin Building that was built there between 1905-1907. The functional plan of this fourth iteration replicates the third one with an open hall for display and sales, and a narrow strip reserved to offices.

During the 20th century the Fulton Fish Market also occupied the New Market Building, which was inaugurated in 1939 by Mayor La Guardia, after pilings of the old market building gave way in 1936 and the entire building slid into the river. Various dealers rented stalls in each building, with closed offices at the back of the stalls.

Left: “Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia dedicating Fulton Fish Market Building” May 19, 1939. Gift of Vincent J. Tatick, Joseph H. Carter, Inc., 1997.006.0001

Right: “Fishmongers standing inside the Fulton Fish Market” 1933. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo, South Street Seaport Museum, 1978.031.0063

In 1979, Barbara Mensch moved to the neighborhood around the Fulton Fish Market. She soon began to photograph the people who worked there, and in order to gain their trust, she showed up night after night, photographing the market as it was rather than trying to romanticize it. Mensch portraits reflect her interest in the individuals who worked there, and her interviews to them –published in “South Street”– are practically unique in the history of the market because a few visitors had cared to talk to the workmen who made the market. Her work reveals the culture of the Fulton Fish Market in ways that simply are not available for earlier periods of this institution’s history.

Left: “Nunzio, an Unloader” ca. 1982 (original negative), 2008. Museum Purchase, 2008.005.0014

Center: “Harry the Hat, Journeyman on Pier 20” ca. 1983 (original negative), 2008. Museum Purchase, 2008.005.0017

Right: “Mombo, An Unloader” ca. 1984 (original negative), 2008. Museum Purchase, 2008.005.0021

The importance of the Fulton market declined in the 1990s and early 2000s because of competing geographic markets such as Philadelphia and the New Jersey docks, and also because of the increasing use of national or regional suppliers. Philadelphia’s market is much smaller in size, but is more convenient for merchants who are located near the area.

Decline and Rebirth

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the seaport was no longer the commercial and transportation hub it had once been. The opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 and the first subway to Brooklyn in 1908 dispersed the crowds that once commuted through the seaport by ferry. By the mid-20th century, many of the old seaport buildings had been neglected and succumbed to demolition. Eventually, the seaport was largely known only for the Fulton Fish Market and its ties to organized crime.

In the 1960s, New York was undergoing one of its most dramatic reinventions. The tension between urban renewal and historic preservation took center stage. After convincing the city to spare the buildings from the wrecking ball, the founders of the South Street Seaport Museum set out to restore the area’s historic structures. They advocated for the creation of the original Port of New York by repopulating South Street with a fleet of historic vessels, and for the establishment of the South Street Seaport Historic District.

In 1980 the Museum and the New York City Economic Development Corporation commissioned to Beyer Blinder and Belle (BBB) a master plan for the Seaport, establishing a framework for restoring the neighborhood while introducing new construction. Expanded with the guidance of Benjamin Thompson & Associates and The Rouse Company, the plan focused on pedestrian-friendly streetscapes and identified key blocks for phased revitalization, guiding the district’s transformation into a dining, shopping, and cultural destination. In 1997, BBB reinvented four levels of a row of historic buildings as a new home for the Museum, from which it could lead its preservation and education efforts.

Today the South Street Seaport Museum and the neighborhood remain a unique New York experiment, both protecting the city’s past and charting a new course for its future.

Additional Readings and Resources

“A History of the Fulton Fish Market” by Priscilla Jennings Slanetz. The Log of Mystic Seaport, p. 14-25, 1985.

“Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898” by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, 1998.

“South Street” by Barbara Mensch, Columbia University Press, 2007.

“Preserving South Street Seaport” by James M. Lindgren, 2014.

“The Fulton Fish Market: A History” by Jonatahn Rees, Columbia University Press, 2022.

“Language City” by Ross Perlin, 2024.

“Taking Manhattan” by Russel Shorto, 2025.

References

| ↑1 | “Markets: The Fulton Fish Market” by Kathryn Graddy. Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, Spring 2006, pp. 207-208. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The governments of New York City and New York State collaborated to collect detailed records of the over 8 million passengers who entered America through Castle Garden. Unfortunately, these documents were lost in a fire on Ellis Island on the night of June 15, 1897. Castle Clinton |

| ↑3 | In 1847, a pier for larger vessels opened on the west side of Manhattan, in the deeper Hudson River, and the City of New York authorized street-level railroad tracks down Manhattan’s West Side, which was already a busy industrial waterfront. This began the eventual transition of maritime activities from the East River seaport to the Hudson River. |

| ↑4 | “Manhattan’s Luxury Liner Row” by William H. Miller, published on Power Ships, Spring 2020, pp. 10-15. |

| ↑5 | John Pintard Papers1750-1925 (bulk 1770-1890). Shelby White and Leon Levy Digital Library, Call No. MS 490. |

| ↑6 | The New York Times, Nov. 18, 1878. |