An updated history of the remains of the hotels inside Schermerhorn Row

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

July 9, 2020

Three years ago our Education Manager noticed a piece of the ceiling in the hallway of the remains of the Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon coming a bit loose, bending into the passageway. From his email notification to the Collections Department about the deterioration, a series of events, investigations, and learning experiences followed, enriching the Museum as a whole in incredible and unexpected ways.

This is the story of how the precious remains of the two hotels inside Schermerhorn Row’s galleries are no longer considered “abandoned ruins,” but effective collections areas to be preserved in their state of deterioration by the Museum’s collection management team.

First and foremost, did you know that the South Street Seaport Museum contains the remains of two different hotels? And do you know why?

After Schermerhorn Row was completed in 1812, the Fulton Ferry terminal opened in 1814, and the Fulton Market in 1822. Soon after, the junction of Fulton and South Streets became a destination for traveling merchants, commuters, and shoppers. Gold prospectors sailing to California and immigrants arriving from Europe also crossed paths along South Street.

To take advantage of this growing transient population, hotels and eateries started to occupy the neighborhood buildings and spaces inside the Row as early as 1821.

Starting in the 1850s Schermerhorn Row’s appearance, both inside and out, began to reflect the shift in usage from trades to lodgers, and the remains of rooms and walls we cherish today are a testimony of the changing fortunes of the building, and the changing of the seaport during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Four major hotels, and hotel complexes existed on the Schermerhorn Row block, some conceived as single isolated units, and others including two or more Row buildings. The remains we can see today are from the Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon and the Fulton Ferry Hotel, both part of the latter category of larger scale businesses.

The Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon opened in 1850 at 4 Fulton Street, as a typical nineteenth-century waterfront refectory[1] Doggett’s New-York City Street Directory, 1850-1851. and saloon, to serve a clientele of seamen and other male travelers and workers. The preserved hotel rooms of this establishment were described in a contemporary guide book as being “splendidly fitted up.”

Mr. Albert Rogers is listed in the Doggett’s New-York City Street Directory until 1864, when he passed the management of his business to Mr. Abraham Sweet, who ran (with additional generations of his family) Sweet’s hotel and restaurant until 1992, expanding it to 6 Fulton Street.

The hotel portion of Sweet’s was abandoned in the 1920s and remained largely untouched throughout the 20th century.

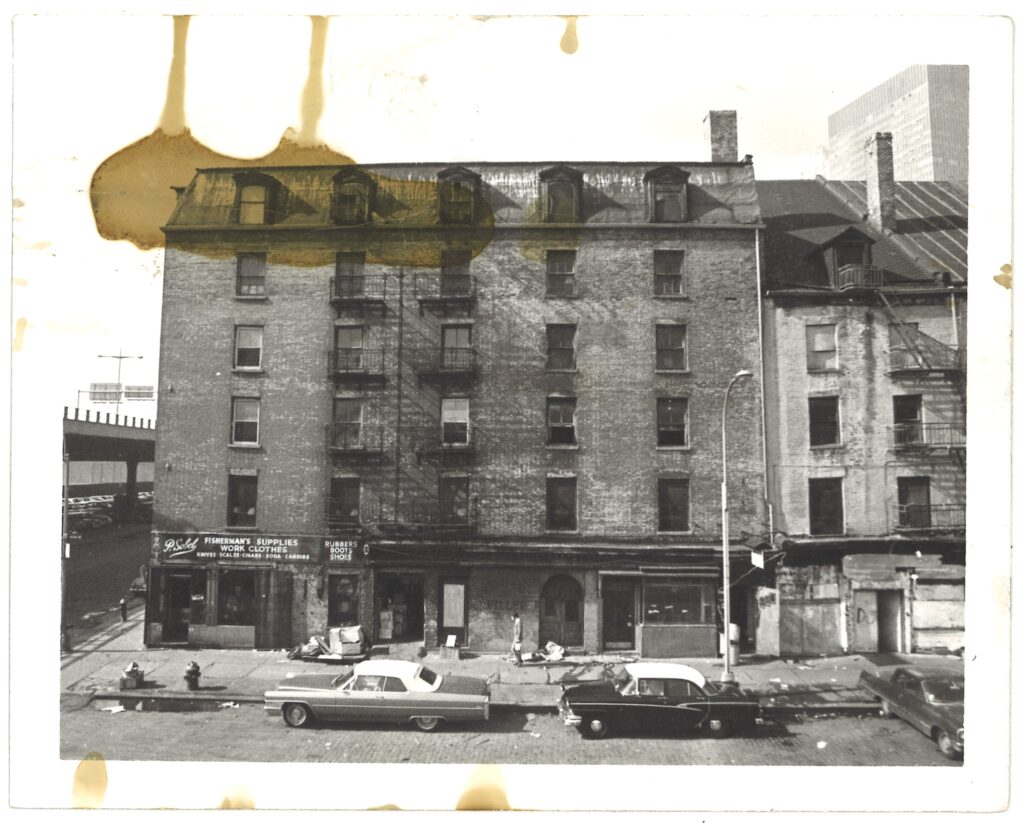

In the case of the Fulton Ferry Hotel, at 92-93 South Street, the business completely transformed the exterior of the original building. The hotel that occupied the same address prior, the Mackinley Hotel, renovated the Row in 1868 by joining the buildings at 92 and 93 South Street, and by adding a mansard roof, creating an additional floor.

Mr. Mackinley remained the hotel proprietor until 1875, when Friederick and Henry Lemmermann assumed the operation of the business and renamed it the Fulton Ferry Hotel. The hotel stayed in business until ca. 1935.

By the 1920s hotel operations in Schermerhorn Row were being abandoned. Hotel rooms and service areas, such as the remains of the Fulton Ferry Hotel laundry room, were simply forgotten; many times the result was all of the upper floors being closed off and only the ground floor business remaining open.

Beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, South Street became a victim of its own success. The continued increase in the volume of shipping traffic and size of steamships was too much for the old seaport to handle alone. The Hudson River waterfront became the new maritime trading hub of the city. At the same time, commuter ferries struggled to compete with the Brooklyn Bridge and new forms of mass transit. With reduced commercial activity (excepting the famous wholesale Fulton Fish Market) and travelers in the area, Schermerhorn Row entered a period of decline, reaching a critical point in the 1960s, when the area was nearly leveled for new developments, but saved by the grassroots preservationists who would become our Museum’s founders.

The long-forgotten remains of the two hotels in Schermerhorn Row were re-discovered in the second half of the 20th century, first by author Joseph Mitchell, and later on by Museum’s staff and the building restoration crew.

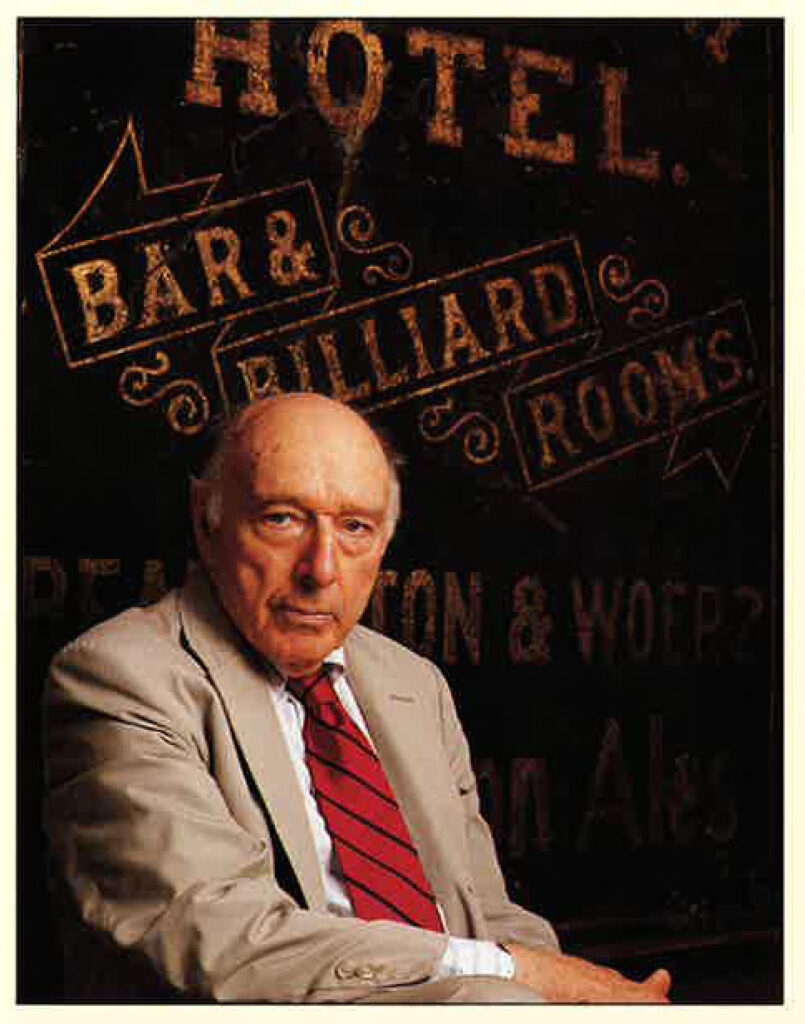

If you have never read the essay “Up in the Old Hotel” by Joseph Mitchell, I highly recommend it to you. I read it at least once a year to be reminded of how this special place came to be, and of the many hidden stories of the almost mythical early 20th-century New York City that is quickly vanishing from our eyes.

Originally written as part of series chronicling unique characters and locales in New York, it tells the story of the rediscovery of the old hotels now preserved in our Museums, as Mitchell and Louis Morino (the owner of Sloppy Louie’s Restaurant, which occupied the ground floors of) climbed through a boarded up elevator shaft to see what was on the upper floors of the building. They were amazed to find the remains of the abandoned hotels, seemingly left as they were on their last day of business, including bedsteads, personal effects, and old signs reading “All Gambling… Strictly Prohibited.”

Aside from immortalizing the seaport district in his essays for The New Yorker, Joseph Mitchell was an avid preservationist and served on the Museum’s Restoration Committee from 1972 to 1980.

Restoration

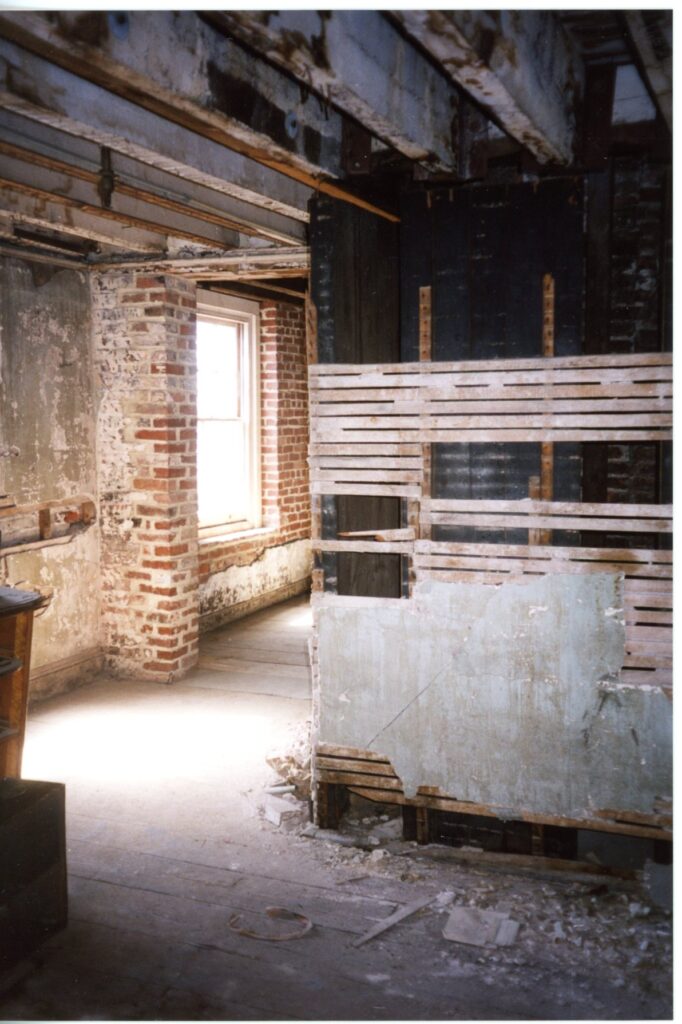

After the Museum’s founding in 1967, plans for renovating the building and its interiors began, including the top three floors of Schermerhorn Row. The exteriors were restored in the early 1980s, while plans to renovate the upper floors, and turn them into gallery spaces, were finally realized in 2000-2001. The Museum staff began clearing the spaces for the contractors to work on-site, and focused their attention on documenting and preserving the historical fixtures of the building: stairs, doors, railings, sinks, bricks, water heaters, etc. as entire sections of the interiors were still intact.

In an article published in the New York Times on February 24, 2002, Mr. Remling, Seaport Museum Curator of Collection, was quoted as saying: “I decided to pull out anything that we wanted saved,” but the demolition crews made more discoveries than expected. Tearing down a plaster wall uncovered 19th-century graffiti left by warehouse workers, and various objects trapped between bricks in an interior wall were also discovered.

Schermerhorn Row’s upper floor galleries opened in the fall of 2003, as the first major new cultural facility to be opened downtown since Sept. 11, 2001. One of the goals in opening the upper floors as galleries was to showcase the building itself as an artifact, so some of the remains of the old hotels could be displayed as ruins “inhabited by the ghosts of immigrants and sailors and young women just off the boat.”[2] “New Body for a Seaport’s Soul; At Maritime Museum’s Remade Home, Old Walls Talk” by Glenn Collins, July 3, 2003.

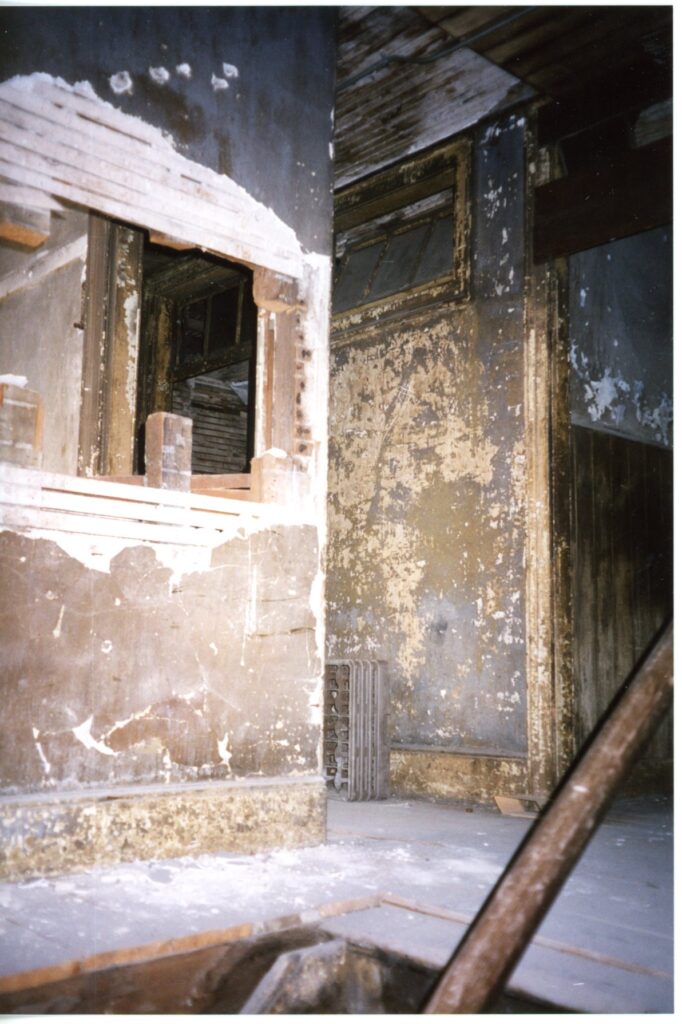

Fast Forward to more recent years when I began working at the Museum in 2015 and found the remains of the hotel in a similar condition to the early 2000s “ruined” interpretation. Most of the rooms in Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon were left halfway covered by plastic sheeting. A thick layer of dust and debris had accumulated in each room’s floor, and the current interpretation was that no one was supposed to touch and walk through them; just use them as “displays” for education programs or tours.

After receiving the email from our Education Manager I mentioned at the beginning of this blog post, I first reached out to a few colleagues and friends who work in historic houses and deal with historic preservation on other sites in New York and the East Coast. Second, I looked into our institutional archives for additional clues and advice from past staff, and third I decided to contact building conservator Mary Jablonski, president and founder of the firm Jablonski Building Conservation, Inc., and an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Historic Preservation program at Columbia University.

Jablonski Building Conservation has worked on a variety of conservation projects throughout the United States and here in New York City, including working preeminently with the Lower East Side Tenement Museum on an ongoing building assessment and stabilization project. The Tenement Museum was an example of similar building type and use in the city to the old hotels of Schermerhorn Row, and former Collection Manager Danielle Swanson was particularly helpful with offering advice and sharing her preservation experience.

Ms. Jablonski came for an initial inspection, and afterwards sent two staff members to do a quick treatment to stabilize the wooden ceiling and the plaster adjacent to it. This series of events made both Ms. Jablonski and I realize that we had a fascinating opportunity in re-assessing the hotels’ condition, and learning from and helping each other. I would benefit immensely from having Jablonski Building Conservation working on the hotels, and Ms. Jablonski’s students at Columbia University’s MS in Historic Preservation would have a perfect hands-on site to study and learn from.

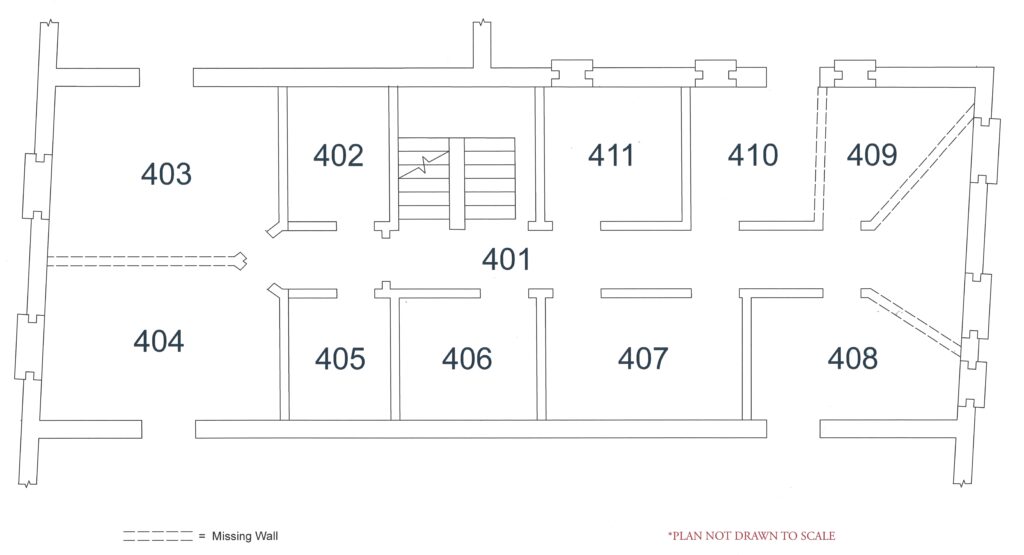

A hands-on workshop plan was put in place for 12 graduate students during the 2018 Spring semester, supervised and guided by Professor Jablonski. The students studied, inspected, tested, treated, and monitored the Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon’s corridor of rooms on the 4th floor of Schermerhorn Row.

This set of rooms on the 4th floor of 6 Fulton Street were added in 1878 as part of the latest complete hotel renovation, and they are the largest of any hotel on the block.

When considering space for the students to work in, the corridor and its various rooms offered more opportunities than, for example, the laundry room of the Fulton Ferry Hotel. The students worked in teams of two or three, were each assigned a room, and each team had unique opportunities for testing various techniques to stabilize the failing paint, wallpaper, and plaster in the rooms.

During the initial research phase, we discovered that all of the buildings and hotels appeared to have a clear distinction between public service areas on the lower two floors, and private rooms on the third, fourth, and fifth floors, but since Schermerhorn Row was originally built for storage, not for habitation, temporary unstable partitions were added to the upper floors to create smaller-size rooms, with no direct access to sunlight, exterior ventilation or heating.

During the inspection, testing, and treatment phases, particular efforts were made to identify and test treatments that were minimally invasive in order to preserve the authentic historic fabric, and were effective based on the composition of the materials of our building.

Following the conclusion of their work, the students produced a detailed report, and gave a presentation to the Museum’s staff and Board of Trustees, including a conditions assessment for each room, with materials analysis and treatment testing.

What happened next?

After this exciting few months assessment, testing, and treatment, the collections management team at the Museum lined up a series of activities that would help us move forward in our next steps.

First, we had to revisit our tour-based programs, most importantly protect the hotels’ environment, and at the same time to strike a balance with activation and preservation. Our goal was to share collections and preservation care culture with the institution staff members first, and then to all guests of our programs.

We decided to keep hosting building tours, but slightly limited the number of guests, and we enhanced them with additional images and information about preservation and housekeeping, which often raised interesting questions and encouraged conversations among the visitor groups.

We also organized a panel discussion as part of Archtober 2018 that explored the unique challenges in public engagement faced by cultural institutions that are also historic sites, which included professionals from the Tenement Museum, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, and Museum of Eldridge Street, and Professor Mary Jablonski. This helped us strengthen connections with colleagues who face similar challenges and opportunities, allowing us to learn from each other.

Second, we implemented a schedule of monitoring and ongoing maintenance to identify active deterioration as soon as possible, which eventually allowed minimally-invasive preventive treatments.

Collection management staff, interns, and selected volunteers inspect the areas every four months, taking photographs of the same walls, from the same angles, looking at debris and losses, and matching particular happenings to additional external forces such as facility improvements or accidents, education and public programs frequency, and neighborhood construction projects.

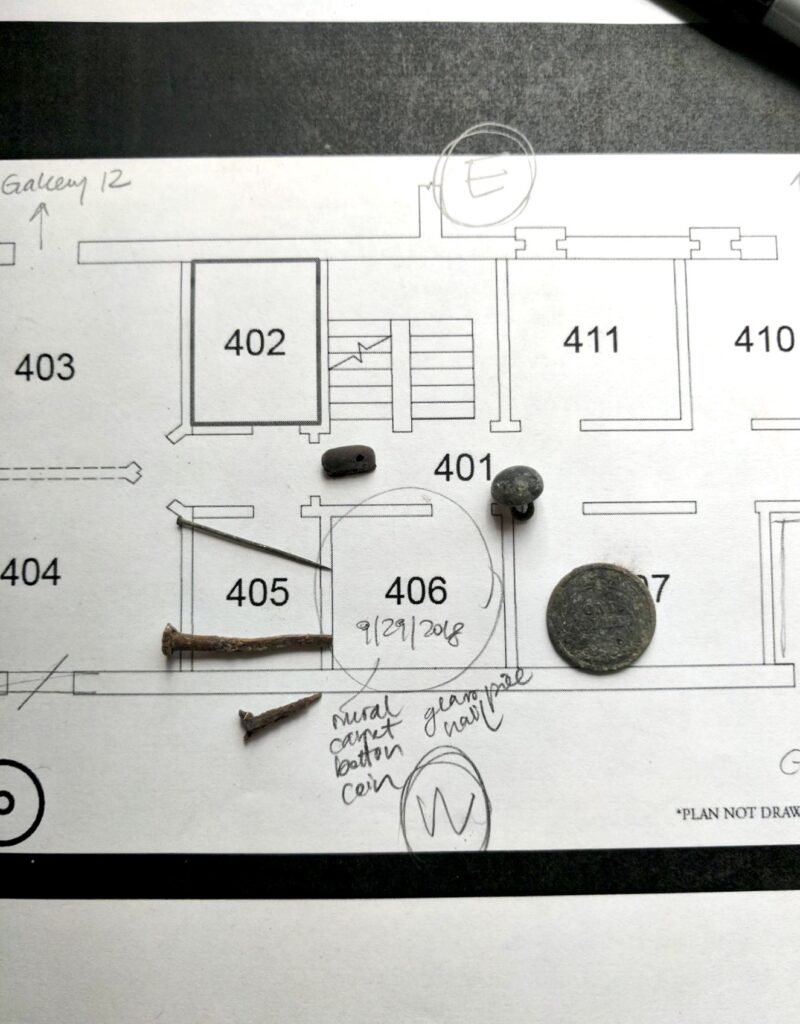

During our first two rounds of cleaning and monitoring, the team sorted through the detritus that had settled between and around the floorboards of the hotel’s rooms, and two types of discoveries warmed our hearts and minds.

We first discovered that under the thick layer of debris and dust, beautiful wood floors revealed usage patterns, and evidence of potential coverage by furniture and carpets, which could help us interpret the room more accurately. Remains of carpet fibers were also discovered, nailed down in corners of room floors and the section of the set of stairs we could reach.

Second, we found a few 19th-century objects most likely owned and brought there by hotel’s residents: a Barber Dime (1892-1916), a small button, a straight pin for sewing, and other loose old nails.

Third, the remains of the hotels have been added to our Collection Management Policy, to explicitly state that the collection management department is in charge of the preservation of these areas. It is a common problem in many institutions that historic building maintenance is shared between departments and staff members, often with no specific chain of command. We are addressing this by making the hotels part of the collections management policy ensuring they are not left in a grey area of shared responsibilities between multiple departments.

Additionally, we’ve updated our gallery guidelines to allow staff and visitors to have an enjoyable and meaningful experience while maintaining the preserved state of these spaces.

Last, but not least, we are working on investigating how to proceed with the production of a Conservation Treatment Plan as part of larger grant opportunities.

After these initial steps, we hope to add an additional level of monitoring and documentation of these spaces by adding each room to our collection management database, and keeping track of images, condition reports, and findings to the cloud-space security of this service.

Over the past few years we’ve learned so much about what it takes to care for these precious spaces. Not only have we had the opportunity to collaborate with professional historic building preservationists and graduate students in this field, but we’ve worked closely with educators and building facility staff members, who also have vital roles in preserving the remains of the hotels inside Schermerhorn Row. Our newest assessments began with a critical observation from our Education Manager, which illustrates and reminds us how important each and every staff member can be.

Suggested readings:

“Up in the Old Hotel and Other Stories” 1992.

“Preserving the World’s Great Cities: The Destruction and Renewal of the Historic Metropolis” by Anthony Max Tung. Three Rivers Press, 2002.

“Joseph Mitchell: mysterious chronicler of the margins of New York” by Tim Adams, published on June 30, 2012 on The Guardian.

“A Place of the Pasts” by Joseph Mitchell, published on The New Yorker on February 9, 2015.

“50 Years of Historic Preservation in New York City” by Ingrid Gould Ellen, Brian J. McCabe, and Eric Edward Stern. Released by NYU Furman Center in March 2016.

Sources:

“A Report on the Occupants and Occupations in the Schermerhorn Row 1811-1890,” prepared for the Board of Trustees of the South Street Maritime Museum, by the Office of State History Senior Curator Jeoffrey Stain, April 1968.

“The Schermerhorn Row Block: A Study in Nineteenth-Century Building Technology in New York City” by John D. Stewart, Richard Pieper, Michael J. Devonshire, Callie Langham, David A. Rosen, and Marilyn A. Simon, for New York State Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, October 1981.

References

| ↑1 | Doggett’s New-York City Street Directory, 1850-1851. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “New Body for a Seaport’s Soul; At Maritime Museum’s Remade Home, Old Walls Talk” by Glenn Collins, July 3, 2003. |