Focusing on the Stories of Maritime Workers

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Elena Abou Mrad, Archives and Special Collections Specialist

August 28, 2025

When telling a story about life at sea, it’s easy to just focus on the captains as the lone heroes at the helm. Maybe the first mate will make an appearance or two. But what about all the other workers, whose tireless labor made everything possible? The stories of the machinists, stokers, and donkeymen (I swear, it’s not an insult) need to be told. Not only do these stories paint a more complete picture of the kind of work that happens on a ship, but they also reveal the true diversity of maritime history: many of these workers were people of color, often immigrants, or emigrant seafarers. The Museum’s archival collections contain stories of hard work, immigration, and activism, which is why I found the Maritime Workers Archival Collection of great interest these days.

The Collection

The Maritime Workers Archival Collection is an artificial collection, which according to the Society of American Archivists’ Dictionary of Archives Terminology is “an intentionally assembled collection of archival resources with varying provenances.”[1]“Artificial Collection”, Dictionary of Archives Terminology, SAA, https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/artificial-collection.html When I explain this to non-archivists, I use the less-than-technical term of “Frankenstein Collection,” since it’s composed of different bits from different sources. In this case, archival materials belonging to different ship workers (and coming from different donations or sources) were brought together at some point around 2012 and most recently, after conducting in-depth archival research to determine the provenance of each group of materials, it was finally time to catalog these documents! Some are grouped as “Papers,” others as individual “Collections,” and some are a single document that is part of a larger donation of items.[2]When there are archival objects that are part of a larger donation that includes artifacts, we assign the title: “First Name Last Name Collection”. When there are several paper-based objects, and … Continue reading

Diverse Professions, Diverse Stories

First and foremost, while cataloging the Maritime Workers Archival Collection, I became familiar with maritime professions that I had never heard about. Here are some of them, for everyone’s clarity:

Able seaman (AB): An experienced deck-department seaman qualified to perform routine duties at sea. Today, ABs perform general maintenance, repair, sanitation, and upkeep of the material, equipment, and areas under the deck department responsibility. Their duties can change from ship to ship, but generally include maintaining and repairing ship parts and gear, operating deck machinery, and serving as the rigger of the ship.

Deck Engineer (or Deck Engineer Machinist): A skilled seaman responsible for maintaining, repairing, and operating deck machinery, including hydraulic systems, cargo fluid systems, internal combustion engines, material handling equipment (fork trucks, pallet jacks, etc.), cargo handling equipment (cranes, booms, winches, etc.), ship’s boats including engines, associated machinery, davits and winches, hull structure (bulkheads, decks, bulwarks, railings), and mooring machinery.

Donkeyman: The operator of a donkey engine, an integrated machine consisting of a power plant and gearing that turns one or more drums or winches containing wire rope. In this 1877 illustration from Harper’s Weekly, you can see a steam donkey engine in the background, in the center-right.

“Scene on a New York Dock—Stevedores Unloading a Ship.” published in Harper’s Weekly on July 14, 1877. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo 1979.272

Fireman: A deckhand who answered to the engineer and primarily stoked the boiler and engines. Stoking the boiler involved keeping the fire going, so the boiler and engines could run properly.

Oilman/Oiler/Greaser: The person who lubricates machinery and performs preventive maintenance on equipment and tools.

Pumpman: A worker who tends, operates, or cares for a pump.

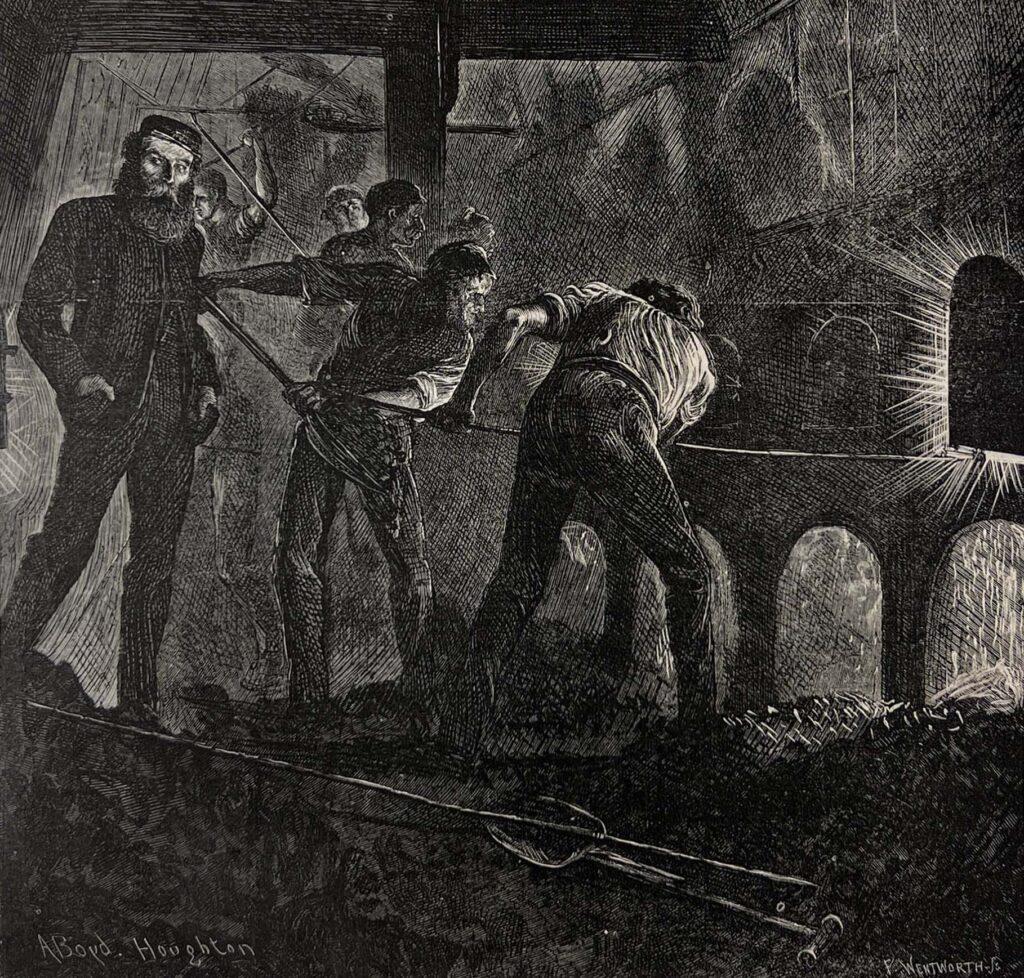

Stoker: The person who manually performs the act of feeding coal or other solid fuel into a furnace, usually supporting the fuel during combustion. You can see some stokers in action in this illustration by Arthur Boyd Houghton (1836–1875) from the Museum’s collections.

Arthur Boyd Houghton (1836-1875), “Stoke Hole of the City of Brussels”, April 2, 1870. Gift of Elizabeth E. Malament. South Street Seaport Museum 1977.004.0005

Trimmer: A worker responsible for distributing coal evenly in the bunkers or holds of ships or in coal storage areas. Their primary duties include ensuring that coal is properly loaded, stored, and accessible, which helps maintain the ship’s stability and efficiency while maximizing the use of available space.

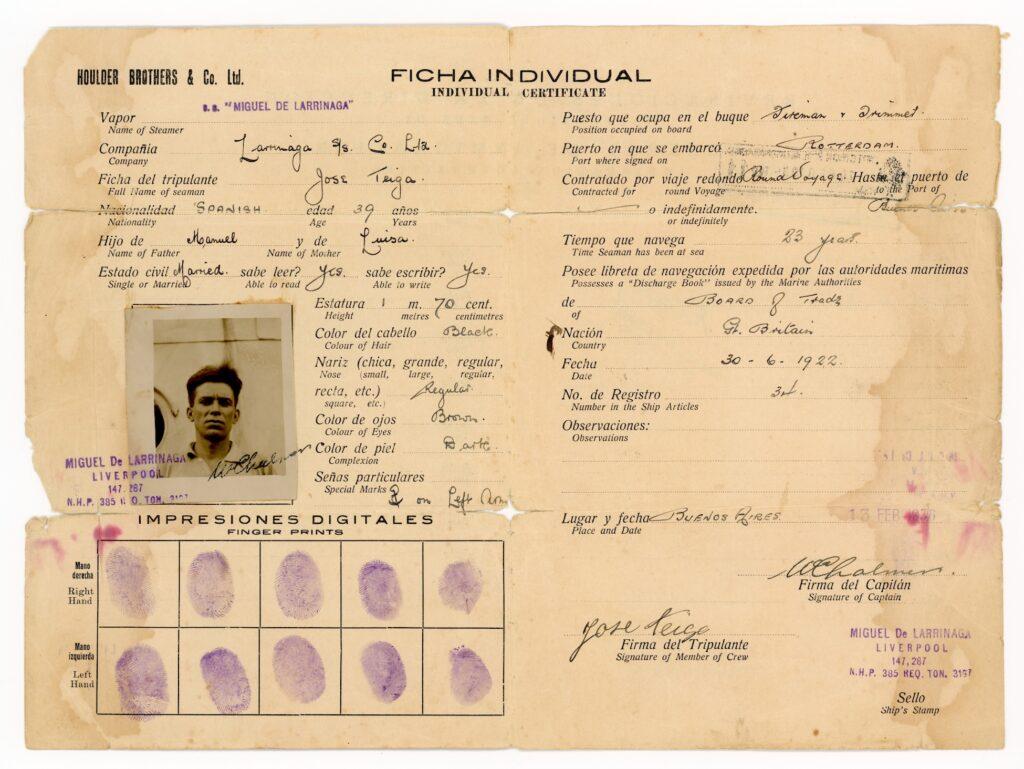

The perfect case study for this nomenclature is the José Teiga Papers, since Mr. Teiga (1896–1969) worked in lots of different roles throughout his career. Born in 1896 in Spain, Teiga traveled the world aboard steam vessels, starting from the rank of stoker at age twenty to Third Assistant Engineer on SS Asta in 1942.

The breadth of his international travel is reflected in his papers, which highlight the diverse nationalities of the ships he worked on and the numerous countries he visited, including Spain, Italy, France, England, the Netherlands, United States, Mexico, Cuba, and the Caribbean region.

José Teiga Seaman’s Certificate, February 13, 1936. Gift of Louise Agnes Teiga 2003.016.0005

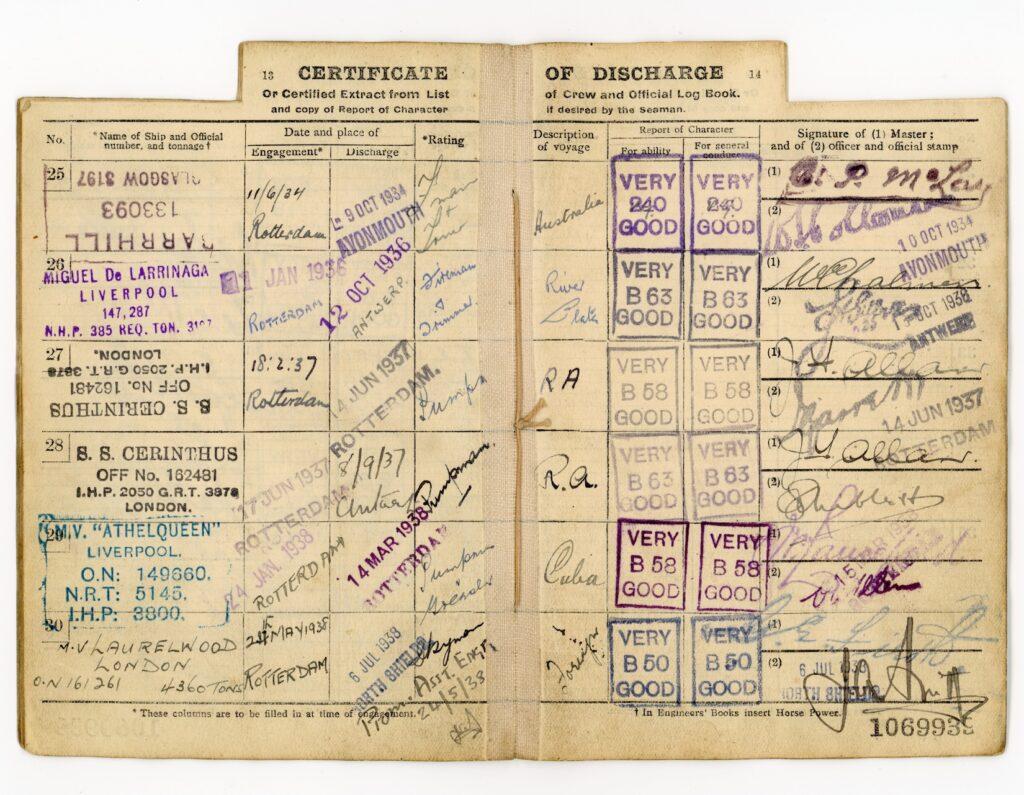

“Continuous Certificate of Discharge, José Teiga”, 1922-1938. Gift of Louise Agnes Teiga. South Street Seaport Museum 2003.016.0004

In order to reconstruct Teiga’s maritime career, I used the information contained in various letters of recommendation and in his certificates of discharge, which are documents containing the records of his service at sea. Many of these documents were transcribed thanks to the dedication of the Archives Program Volunteers[3]The Archives Program Volunteers help with digitizing and transcribing records and photographs related to Seaport Museum Archives. Projects include scanning photographic materials and cataloging … Continue reading, which made it much easier for me to gather all this information. Here’s a brief list of Teiga’s work life, which took place between the two World Wars:

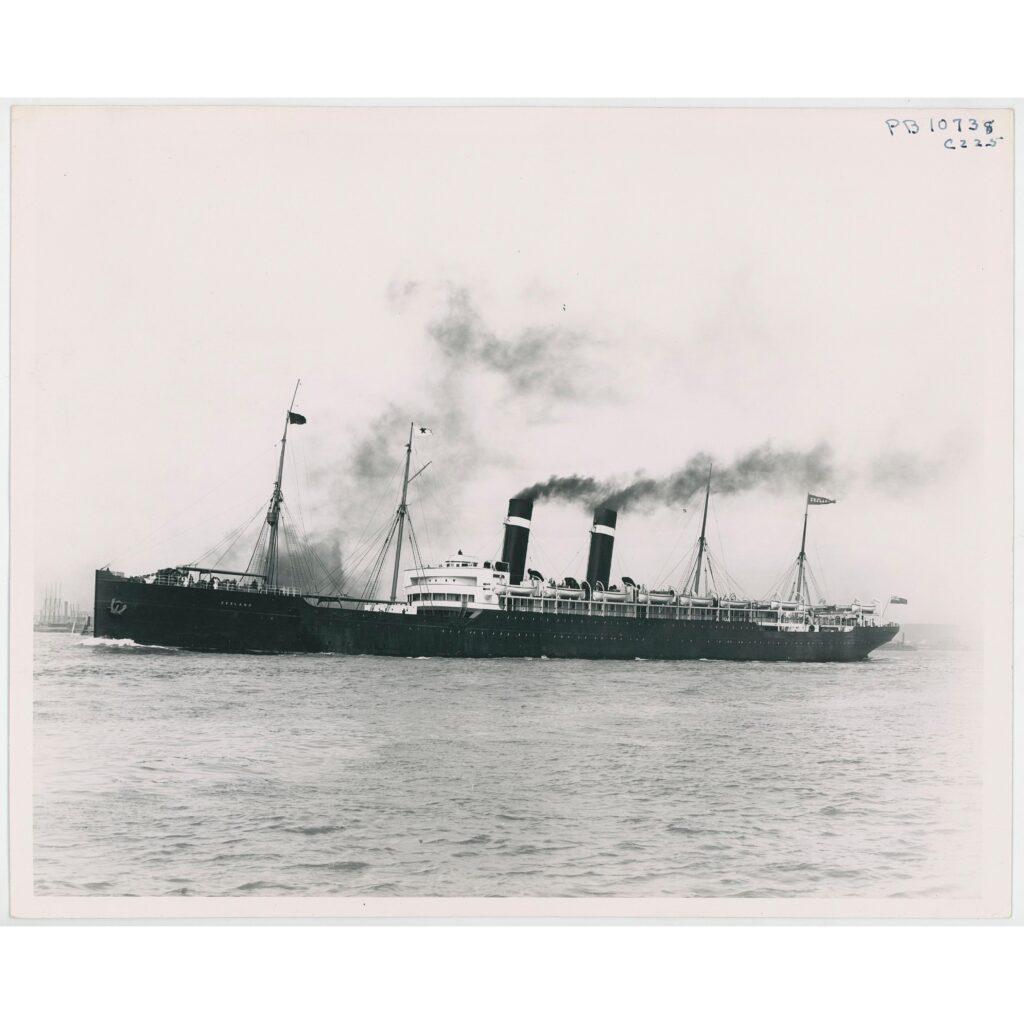

1916–1917: Stoker on SS Texel and Zeeland; oiler-stoker aboard Bellatrix; able seaman (AB) on N.V. Sleepboot Wilhelmina

1918–1919: Donkeyman aboard Sint Jansland and SS Rosa; “chauffeur” (conductor or helmsman) aboard steamship SS Elisabeth van Belgie; able seaman on SS Java; oilman on SS Rijsbergen

1921–1925: Deck engineer aboard SS Eastern Coast; donkeyman on SS Saint Patrick and SS Heerenveen; fireman and coal trimmer aboard Asturian; donkeyman aboard Hornby Castle; donkeyman and greaser aboard SS Queen Eleanor, Caldy Light; attendant on SS Aviemore

1926–1931 Fireman and trimmer aboard Essex Abbey, SS Admiral Hamilton, Manchester Hero, Haworth, Cambrian Express, and Graceful; donkeyman aboard SS Golden Sea and Casanare

1931–1934: Fireman and trimmer on Patuca, Marcella, Barrhill, and Miguel De Larrinaga

1937–1938: Pumpman on SS Cerinthus; pumpman and greaser on MV Athelqueen; donkeyman (then promoted Assistant Engineer) on MV Laurelwood

1941–1942: Fourth Assistant Engineer aboard SS Panam, Third Assistant Engineer aboard SS Asta.

Left: [Group photo with José Teiga], ca. 1920s-1940s. Gift of Louise Agnes Teiga 2003.016.0073

Center: [José Teiga and a sailor posing next to a cannon], ca. 1920s-ca. 1940s. Gift of Louise Agnes Teiga 2003.016.0077

Right: A.B. Deitsch, “Zeeland (Red Star)”, n.d. Copied by the Mariners Museum, Newport News, Virginia. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

The Importance of Maritime Unions: the Example of the NMU

Until the early 20th century, maritime unionism had represented a predominantly white and skilled workforce. Around the start of the century, the movement shifted to include rank-and-file sailors fighting for labor rights and demanding improved working conditions at sea, direct control over hiring and relief, and the recognition of the principles of industrial solidarity.

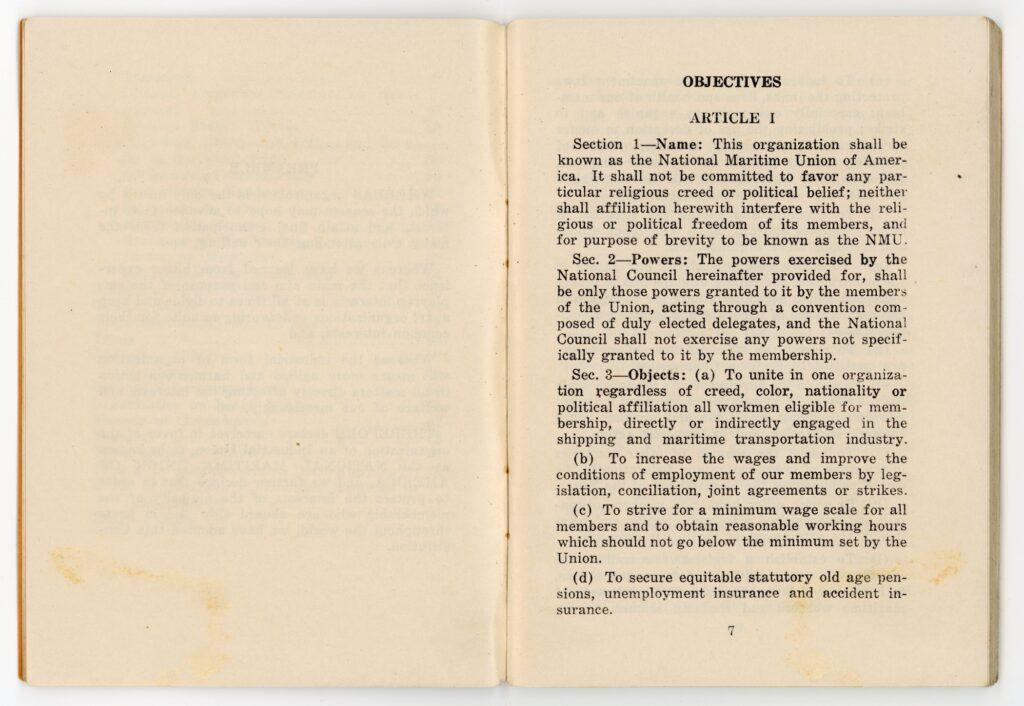

The National Maritime Union (NMU), founded in 1937, became the dominant seamen’s union on the East and Gulf Coasts of the United States by the end of World War II. In 1946, the NMU had 46 branches, a staff of 500 employees, a payroll totaling $1.5 million a year, and a membership of 73,000[4]”LABOR: Politics & Pork Chops”, TIME, June 17, 1946. https://time.com/archive/6783938/labor-politics-pork-chops/. One of the main goals of the NMU was combating racial discrimination and fighting for the rights of all seamen, regardless of skill, shipboard rank, or ethnic group. This principle of non-discrimination is listed in the opening page of the NMU Constitution (Article 1, Section 3a):

“Sec. 3–Objects: (a) To unite in one organization regardless of creed, color, nationality or political affiliation all workmen eligible for membership, directly or indirectly engaged in the shipping and maritime transportation industry.”

Knickerbocker Press, Inc., printer. Constitution of the National Maritime Union of America, 1937, pages 6-7. Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie 1995.008.0034

In an era when racial segregation was very much the norm, the NMU advocated for federal civil rights laws (including an anti-poll tax and anti-lynching legislation) and made it a policy to send out mixed-race crews on ships.

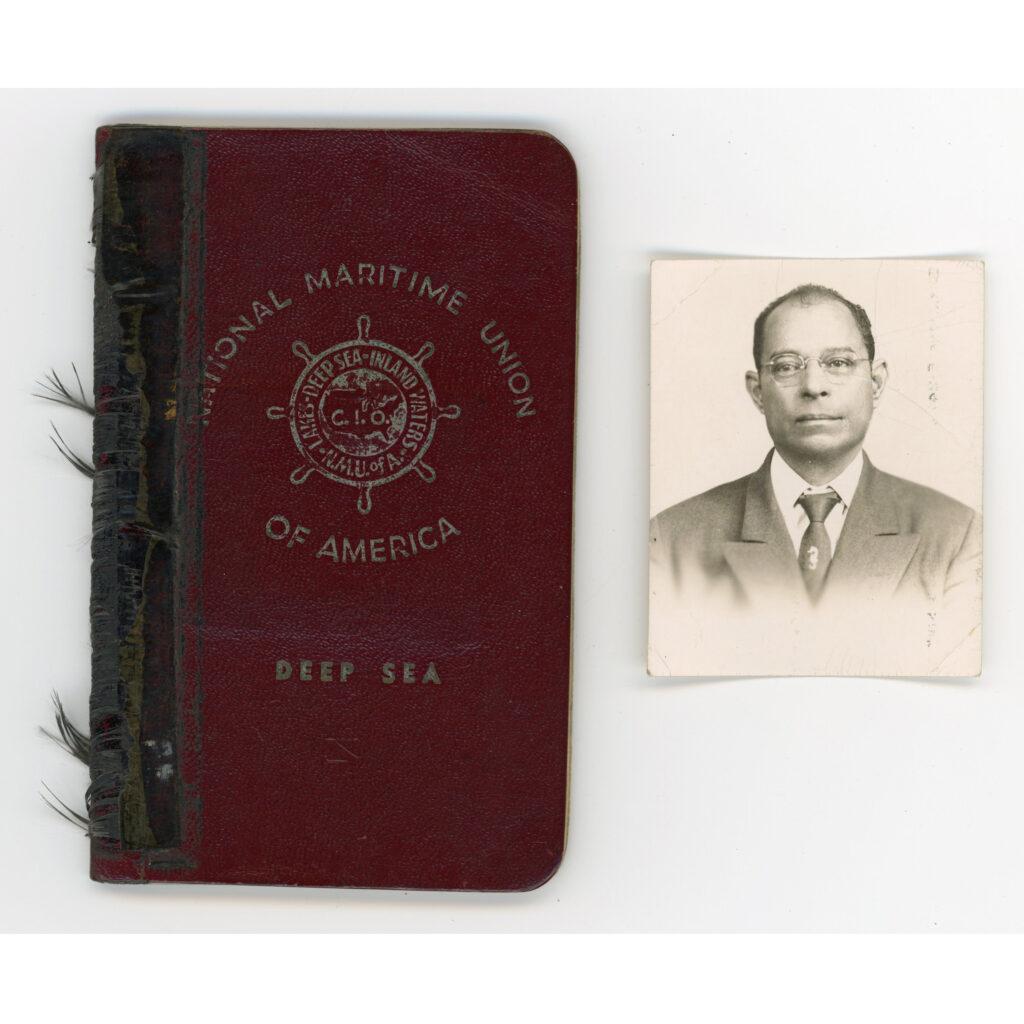

The best example of this labor rights activism is the Egbert J. L. Jap-Ngie Collection. Egbert Jacob Lucius Jap-Ngie (1899–1968) was born in Paramaribo, Suriname (then Dutch Guiana) to a Dutch father and a Chinese mother.

At the age of 13, he shipped out as a cabin boy, eventually commanding a four-masted schooner that carried mail between Caribbean and North American ports.

In the 1920s he became a licensed ship’s captain in the United States, but had difficulty obtaining work as a steamship commander, a problem he attributed to racism.

Jap-Ngie worked as ship’s captain for the schooner Mabel and the schooner W.H. Marston—you can actually see a reproduction of an original photograph of him using a sextant aboard Mabel in the Museum’s exhibition Maritime City!

[Egbert Jap-Ngie holding a sextant with his crew on schooner Mabel], ca. 1920. Reproduction. Gift of Walter Jap-Ngie, 2000.014.0001

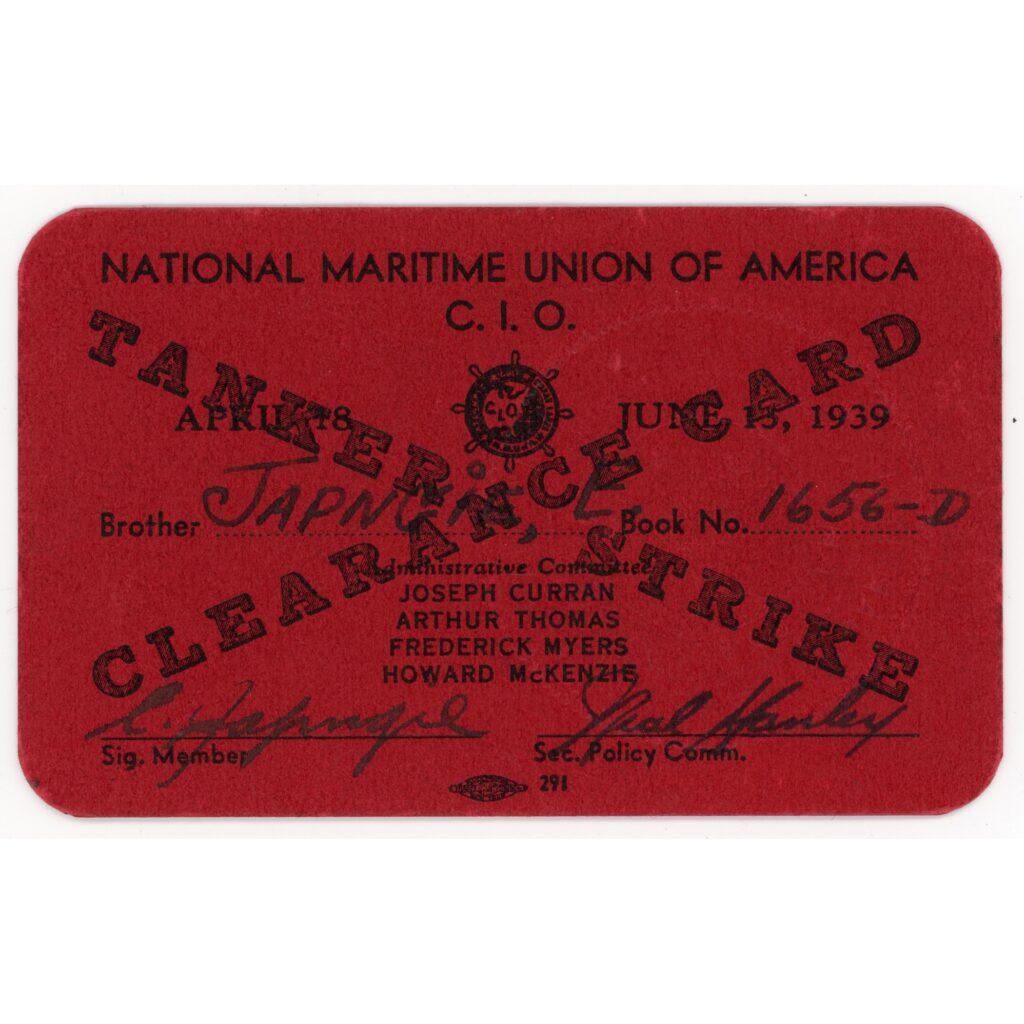

Jap-Ngie was a founding member and an officer of the National Maritime Union (NMU) and was active as a ship’s chairman and delegate from 1937 to at least 1965. Jap-Ngie was a ship organizer in the Red D Line (Atlantic & Caribbean Steam Navigation Co.), the Clyde Steamship Company, the Columbia Line, the Porto Rico Line, and the Grace Line. He was elected twice as a delegate to the First and Second Constitutional Conventions of the NMU in 1937 and 1939. Jap-Ngie was elected in 1950 to his first term of office in New York and was re-elected as Patrolman in 1952. His service as NMU representative is well-documented by a variety of archival materials, including booklets, pins, and cards.

Left: Robin Hood Press, Inc., printer. “National Maritime Union of America Membership Book”, 1950-1956 (printed August 1950, issued December 3, 1952). Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie, 1995.008.0026.A-.B

Center: “National Maritime Union Delegate Pin”, October 7, 1963. Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie, 1995.008.0005

Right: “National Maritime Union Tanker Strike Clearance Card”, April 18-June 13, 1939. Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie. 1995.008.0037

Maritime Professions: a Family Affair

One thing that struck me while archiving the Maritime Workers Archival Collection is the focus on their families. Egbert J. L. Jap-Ngie, for example, had ten children, and all of his seven sons spent some time at sea. His youngest son, Walter C. Japngie (born 1950), was a labor negotiator for the New York State Nursing Association in and around the Port of New York. A testimony to the Jap-Ngie family’s pride in maritime professions is the United States Maritime Service Officers School Graduation Program, dated June 28, 1944. Jap-Ngie probably kept this booklet as a memory of Egbert Albert Japngie’s (his firstborn son, 1924–1993) graduation from the United States Maritime Service. On page seven, his name is listed in the section “GRADUATES / SECTION 3201 – ENGINEER / LIEUT. (JG) W.R. HAINLINE”—although misspelled as “JAPGNIE.”

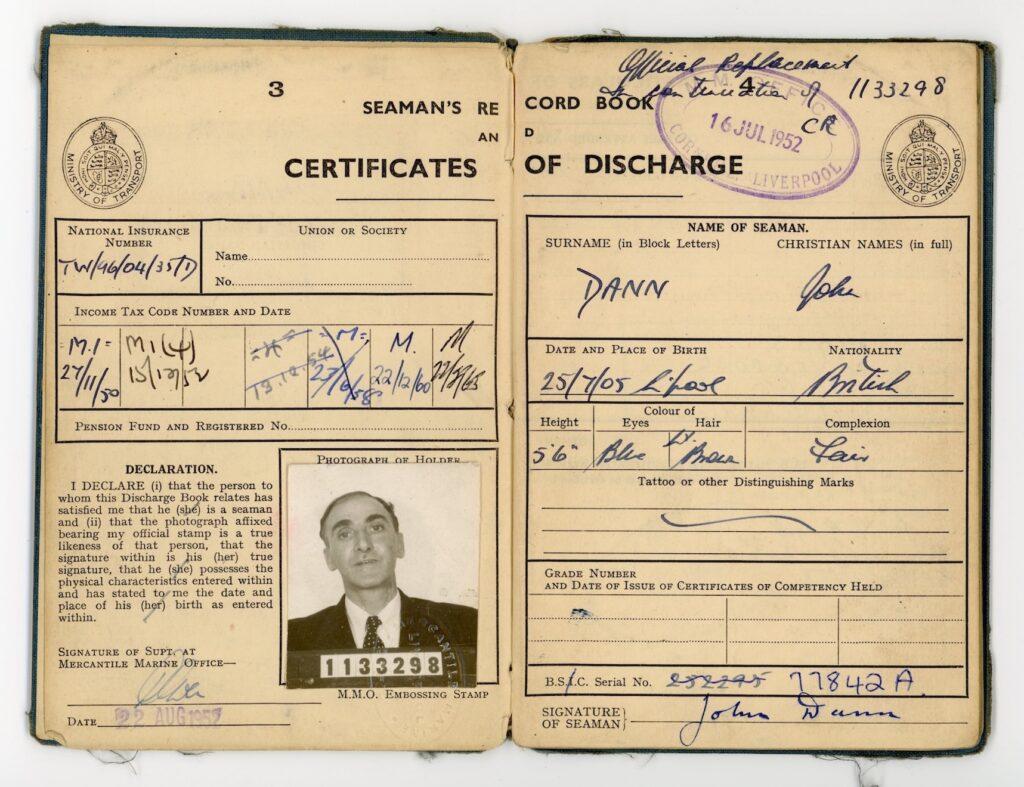

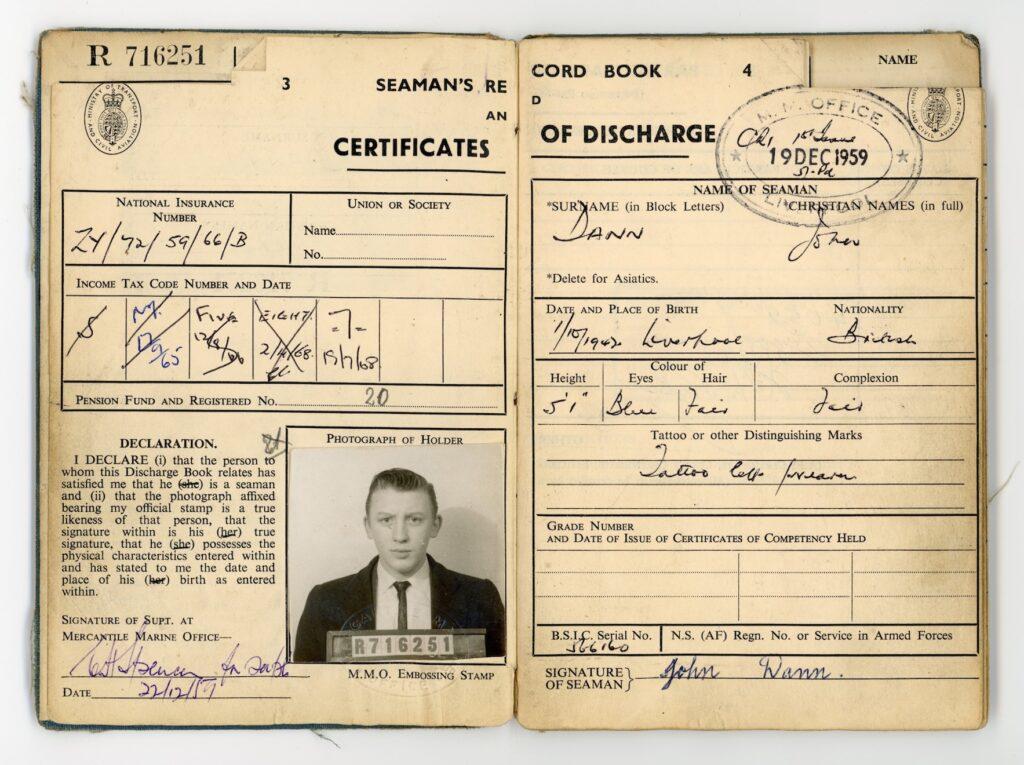

Another example of this family history of maritime work is in the John Dann Papers. When inventorying the certificates of discharge for a seaman named John Dann, I noticed that most of them belonged to a middle-aged gentleman (born in 1905), while one of them had a picture of a young man (born in 1942). A quick look at the page for their next of kin cleared any doubts: Mary Dann was the wife of the older John Dann and the mother of the younger one! From his next of kin page, you can see that John Dann Jr. changed his emergency contact from his mother Mary to his wife Doreen after he got married.

Left: Ministry of Transport, issuer. “Seaman’s Record Book and Certificates of Discharge, John Dann”, 1952-1968. Gift of John Dann, 1997.049.0006.A-.D

Right: Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, issuer. “Seaman’s Record Book and Certificates of Discharge, John Dann”, 1959-1969. Gift of John Dann, 1997.049.0007.A-.B

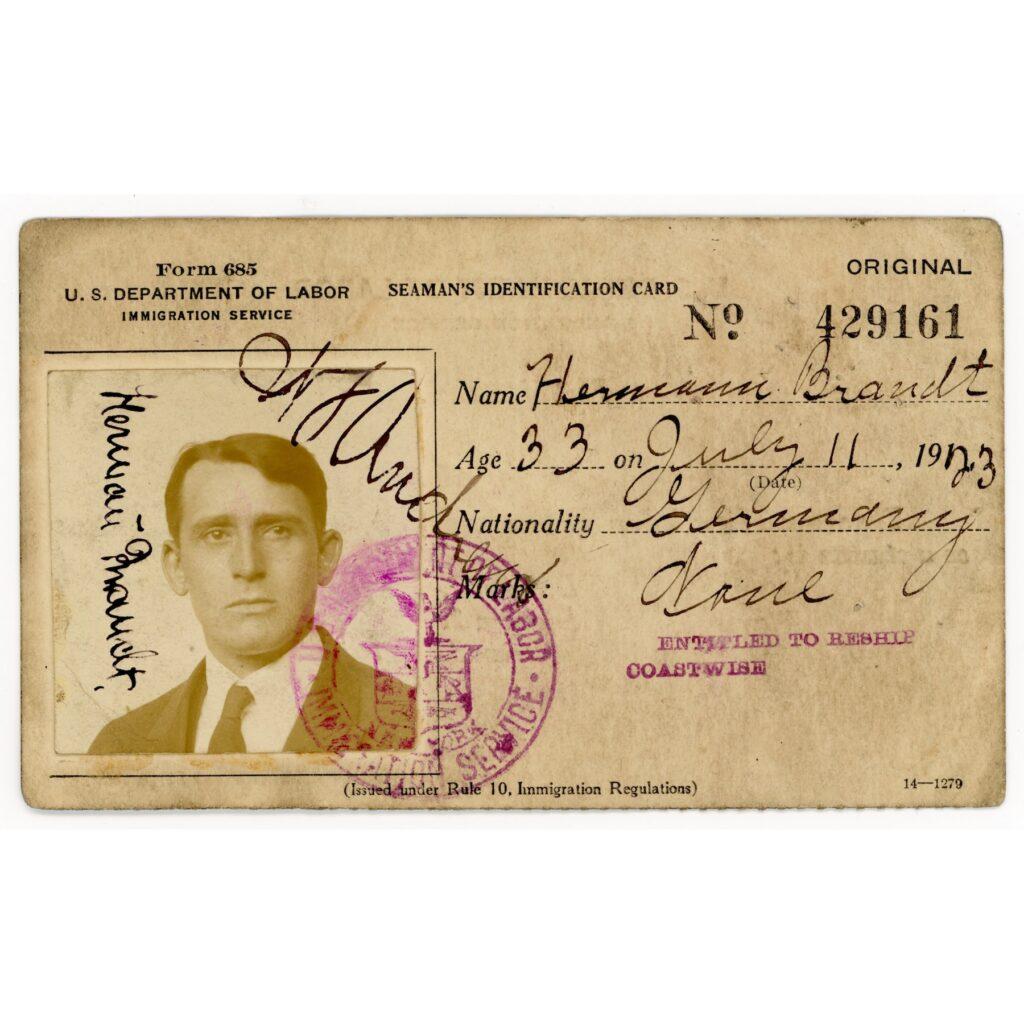

The Stories Are in the Details

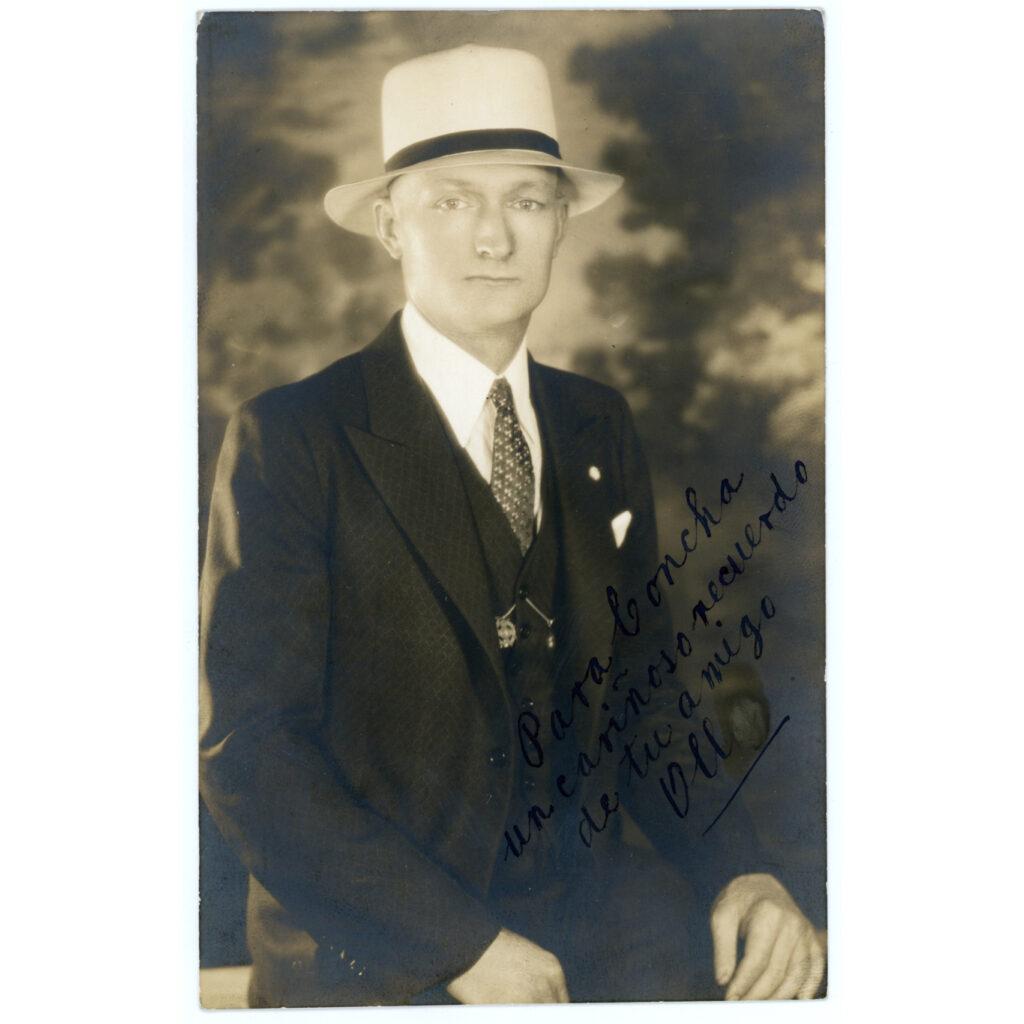

When looking at the documents in the Maritime Workers Archival Collection as a whole, certain recurring themes start to appear: most of these men went out to sea when they were really young, doing hard, often dangerous work. For many of these workers, immigration is another common thread. Herman Brandt (born 1890) immigrated from modern-day Poland; Egbert J. L. Jap-Ngie from modern-day Suriname; Olaf Jordan (born ca. 1890) from New Zealand; Leon J. Martin (born ca. 1931) from the United Kingdom; José Teiga was born in Spain and immigrated first to Belgium, then to the United States.

The dedication and tenacity of these workers emerges from the details, like the fact that John Dann did not take much of a break between different voyages, as is attested in his certificates of discharge. Gregory L. Brownson (1929–1983) earned a Certificate of Apprenticeship as Shipwright in 1962, documenting that he invested time and effort to learn a maritime profession. The fact that José Teiga kept twenty-one recommendation letters speaks to his work ethic and the pride he took in his work.

Left: [José Teiga’s passport photo], ca. 1920s-ca. 1940s. Gift of Louise Agnes Teiga, 2003.016.0067

Center: [Portrait of Olaf Jordon], n.d. Gift of Mrs. Olaf Jordan 1974.029.0044

Right: Seaman’s Identification Card for Hermann Brandt, April 3, 1924. Gift of Elizabeth Lusk 1989.060.0014

Cataloging these archival materials opened a larger conversation within the Collections Department: What other archival materials in the Museum’s archives are related to maritime workers? What other maritime professions have been overlooked? Are these documents and images connected with artifacts in the Museum’s collections? And if so, how can we make these stories more connected and meaningful?

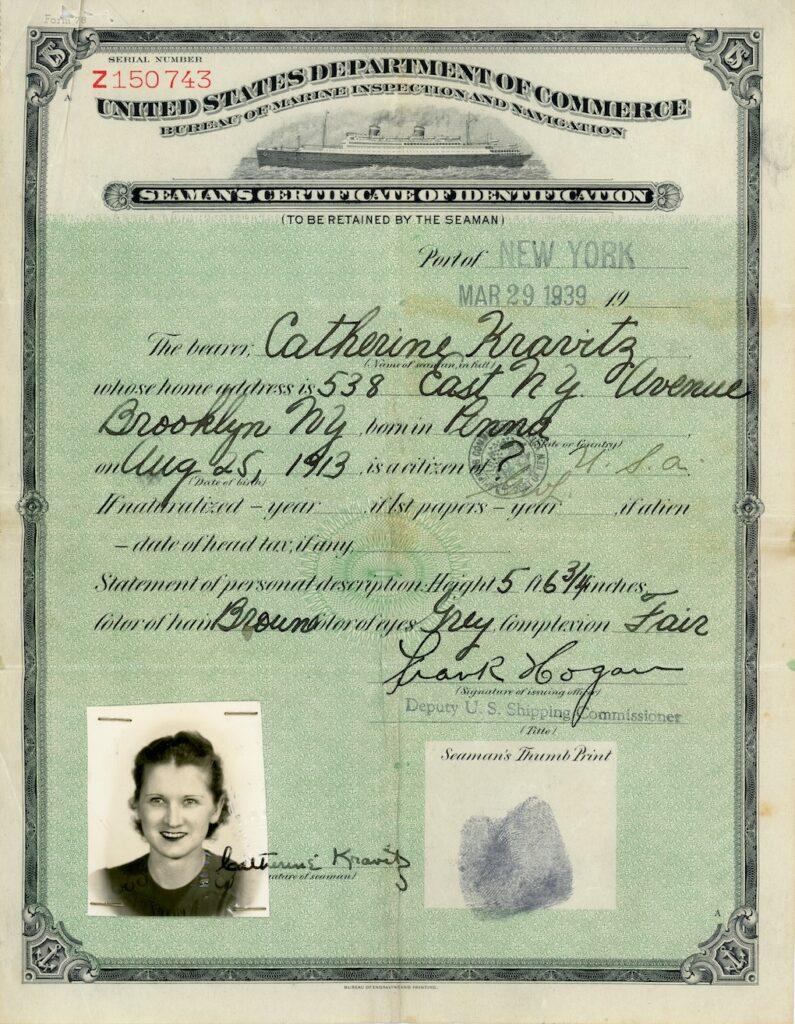

One example that immediately came to mind was tied to a recent acquisition of the documents belonging to Catherine Kravitz (born 1913), a nurse who worked on ships including SS Argentina and SS Santa Lucia during World War II.

Her documents were not added to the Maritime Workers Archival Collections as this artificial group was not assessed and defined at the time of acquisition, but are a testimony to the changes that were taking place in the maritime workforce in the mid of the 20th century, like the gradual opening to women professionals.

An interesting sign of this time of transition is Kravitz’s Seaman’s Certificate of Identification, where she is referred to as a “seaman”—a sign that institutionally, maritime professions were still seen as distinctly male-dominated.

US Department of Commerce, Port of New York. “Catherine Kravitz’s Seaman’s Certificate of Identification”, 1939. Gift of Paul Hofmann 2018.006.0007

According to the International Chamber of Shipping, there are an estimated 1,892,720 seafarers currently serving on internationally trading merchant ships. By serving as able seamen, oilers and greasers, pumpmen, and more, seafarers across the globe are continuing a long tradition of maritime work. It was a privilege to catalog this collection and to have a window (or better, a porthole) into the lives of these workers. There are too many stories to fit into a blog post, but my hope is that these few examples will shine a light on the dignity and importance of these professions, many of which continue to this day.

Additional Readings and Resources

City of workers, city of struggle. How labor movements changed New York, edited by Joshua B. Freeman, Columbia University Press, 2019. In association with the exhibition City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York at the Museum of the City of New York.

History of American Merchant Seamen, by Elmo Paul Hohman, The Shoe String Press, Hamden, Connecticut, 1956.

Merchant Seamen. A Short History of Their Struggles, by William S. Standard, International Publishers Co., Inc., 1947.

Labor on the Waterfront. Highlighting Professions That Helped the Growth of the Port of New York. A Seaport Museum Collections Chronicles Blog by Carley Roche, Collections and Archives Intern, September 3, 2020.

Shipping goods across the oceans. A brief history of cargo and container ships in New York. A Seaport Museum Collections Chronicles Blog by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections, April 29, 2021.

References

| ↑1 | “Artificial Collection”, Dictionary of Archives Terminology, SAA, https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/artificial-collection.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | When there are archival objects that are part of a larger donation that includes artifacts, we assign the title: “First Name Last Name Collection”. When there are several paper-based objects, and they are not part of a larger donation that includes artifacts, we assign the title: “First Name Last Name Papers”. |

| ↑3 | The Archives Program Volunteers help with digitizing and transcribing records and photographs related to Seaport Museum Archives. Projects include scanning photographic materials and cataloging records, organizing and describing image files, and transcribing handwritten documents into digital formats. Learn more about the Archives Volunteer Program in the Collections Chronicles Blog post “Cursive Conundrums”. https://southstreetseaportmuseum.org/cursive-conundrums/ |

| ↑4 | ”LABOR: Politics & Pork Chops”, TIME, June 17, 1946. https://time.com/archive/6783938/labor-politics-pork-chops/ |