Highlighting Professions That Helped the Growth of the Port of New York

A Seaport Museum Blog

by Carley Roche, Collections and Archives Intern

September 3, 2020

When thinking about New York City, what comes to mind? Usually tall buildings, crowded subways, and bustling streets filled with pedestrians. But if we peel back the urban layers we find there is so much more to discover. There are beautiful parks, a diverse wildlife, and an incredible coastline. With 520 miles of shoreline meeting rivers, bays, and the Atlantic Ocean- New York City boasts a remarkable waterfront. Along these different shores men, women, and children of all backgrounds have worked together trading and selling food, goods, and news with one another.

Labor Day is approaching as I write this post, and I wanted to highlight some of the professions that have been seen while walking along New York City’s vast coastline throughout the centuries, as I keep seeing them represented in the works of art I am cataloging and researching in the Museum’s collections. From working long months out on rough waters to endless hours manning a storefront, the following are just a few of the positions that have helped the Port of New York to become one of the most important locations in history, a national economic dynamo, and the busiest port in the Western Hemisphere by 1870.

Stevedores

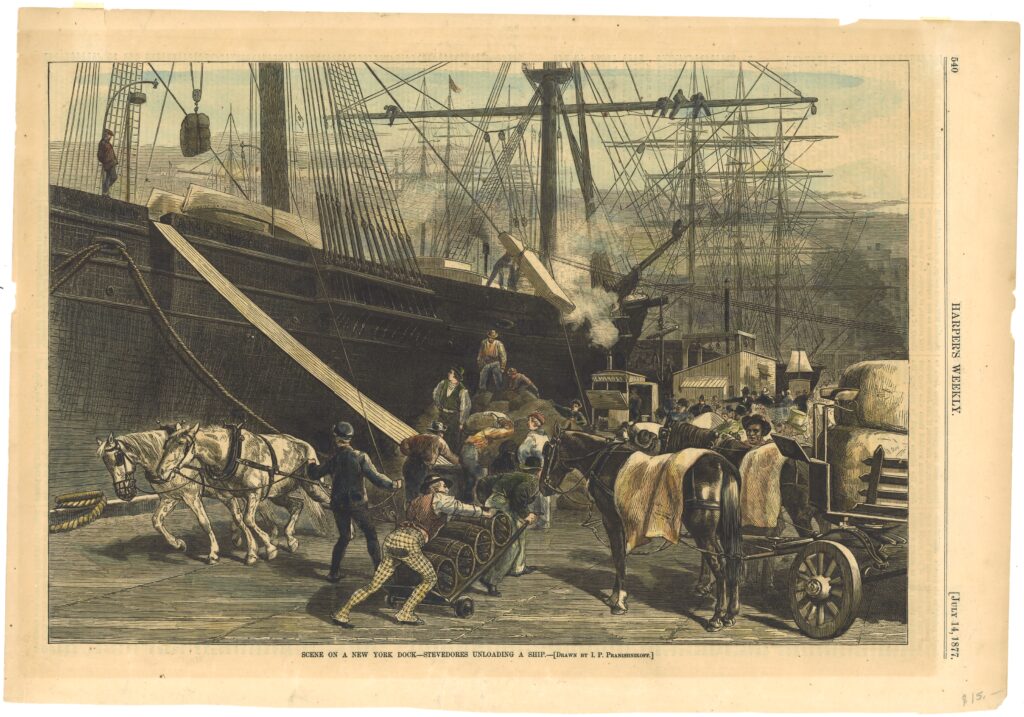

Along the docks of New York City’s harbor one would see men unloading cargo filled with exotic foods, supplies for local shops, and general goods and wares to be transported further inland.

Stevedores- also known as dockworkers or longshoremen- have been central figures along waterways throughout history. An incredibly dangerous job, these men needed to have specific knowledge of handling heavy cargo in order to load and unload ships properly and safely.

“Scene on a New York Dock—Stevedores Unloading a Ship.” published on Harper’s Weekly on July 14, 1877. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo, 1979.272

Stevedores needed to be physically strong and attentive of their surroundings to ensure all merchandise made it to their final destinations without any loss of profit or harm to the crew.

Early stevedore work in New York City was seen as a ticket to freedom for many enslaved men as, “Ship owners, ship captains and maritime business operators when hiring workers were often more concerned with muscle and maritime skills than skin color or enslaved status”[1] “Blacks on the New York Waterfront During the American Revolution” by Charles R. Foy, 2016 . In the 18th Century, as New York’s harbor was beginning to transform into a burgeoning economy, the need for able bodied workers outweighed biggoted views based on skin color. Stevedores were hired for their strength and Black individuals, enslaved or free, used this fact to secure employment.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the boom in immigration saw a shift in who participated in stevedore work. In New York City it was “estimated that as late as 1880, 95 per cent of the longshoremen in both foreign and coastwise commerce were Irish and Irish-Amerians, the remaining 5 per cent being Germans, English, and Scandinavians”[2] THE LONGSHOREMAN. (1916). Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2(5), 1-7. Retrieved August 31, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41822971. The captains and owners who selected men to work on their ships did not care about any possible language barriers, but, again, just the strength of a man and his ability to complete the job.

Corruption and bribery were large shadows hanging over the life of stevedores. Those who selected men to work were easily swayed by money to choose certain men.

In 1953, the Waterfront Commission was formed to stamp out this corrupt practice. By 1955, hiring halls had been set up at different locations along New York City’s waterfront for dockworkers to “badge-in”. This practice allowed the Commission to keep track of worker’s hours and dole out work according to seniority rather than economic status.

However, stevedore work in New York City plummeted around this time with the introduction of containerization. Large areas of space were needed for the new metal containers used to transport merchandise, which New York City could not provide.

[Dock workers standing outside Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor Employment Center 16], ca. 1965. Gift of the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor, 1997.020.0021

The Red Hook neighborhood in Brooklyn is still home to a container shipping terminal, but by 1971, all other shipping companies had moved locations to New Jersey, thus essentially ending centuries long stevedore work in New York City.

Sailors

Of course there would be no ships, ports, or merchandise without sailors. Ensuring the safe transportation of cargo to different cities all across the globe as well as maintaining whatever ship they were working on sailors have played a crucial part of trade and naval history.

Facing excruciatingly long journeys and extreme weather, sailors faced dangers on the seas to assist the maritime economy around the world. Sailors need to know navigational skills, cargo handling, the ins-and outs- of different vessels, and have general grit to last the long months at sea.

Much like stevedore work, sailors were heavily integrated despite American laws enslaving or restricting employment for Black people. “The close quarters, the shared hardship, the isolation from land-bound social forms–all contributed to a general lack of prejudice among seamen”[3] “The Black Man and the Sea” by S. Canright, published on South Street Reporter, Vol. VII, Winter 1973-1974, pp. 5-10.

Gordon Grant (1875-1962), “Sailor waving signal flags” 20th century. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection, 1991.071.0126

Many enslaved men were trained sailors outright, with records showing that many were sold highlighting these skills. Life at sea was a way to escape enslavement and earn a free living in free states and in foreign ports.

Women also found their way aboard ships, but in secrecy. Disguising themselves as men, women sought better wages or to live a life without gender-based restrictions[4] “Women in New York City’s Maritime History” by Anna B. Baaske-Rodriguez, Mar 12, 2013. The life of a sailor, though harsh and unforgiving, gave many men and women opportunities that were forbidden to them on land.

Chandlers

Above left: “Transitional Smooth Plane” made by Fulton Tool Co., early 20th century. Gift of Mr. Arthur Steinberg, 1980.274.0032

Above center: “Keyhole Saw” made by Henry Disston and Sons, late 19th century. Gift of Mr. Arthur Steinberg, 1980.274.0075

Above right: “Steel adjustable S-wrench” early 20th century. Gift of Arthur D. Steinberg, 1986.046.0082

Sailors and ship captains could not complete their work without tools and supplies for their long voyages, so they would seek out chandlers to purchase these items. In Medieval times, a chandler was a candle maker and very important to ship workers prior to the invention of electricity. As the maritime economy grew and sea trade expanded, chandlers began stocking up on all items needed for successful trips at sea. From sails and ropes to tools and oils, chandleries became the one-stop shop for all seafaring needs. Working all hours of the day as ships came in to dock or left port, a ship chandler was essential to the success of a voyage and the maintenance of a ship.

Chandleries are incredibly important along ports and became increasingly more common as the Port of New York grew.

Peter Schermerhorn (1749-1826), developer of Schermerhorn Row (the 1810-1812 row of countinghouses the Seaport Museum calls home), also worked as a chandler. His store, located at 243 Front Street, had direct access to the water along the tip of Lower Manhattan from 1799 until 1818. Then he and his neighbor, Ebenezer Stevens, filled in this area of land to develop South Street[5] “Saved from the Wrecker’s Ball,” by E. Fletcher, published on Seaport Magazine, Summer 1983, pp. 31-38.

L. Prang & Co., lithographer, “L. Merchant & Co., Ship Chandlers and Grocers” ca. 1860. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, 1991.070.0258

The largest ship chandlery in the nation could once be found in the Seaport District: Baker, Carver & Morrell. With its beginnings dating back to 1827 and open for business for over 150 years, this chandlery served grand iron-hulled ships to modern ocean liners[6] “Baker, Carver & Morrell” by E. Rosebrock, published on South Street Reporter, Vol. IX, Summer 1975, p. 11. Another famed chandlery is William H. Swan & Sons, Inc., which began operations in 1874. They, too, worked into the 20th century evolving alongside the needs of modern ships.

Printers

The Port of New York- with its merchants, grocers, and sailors- would not have been successful without the aid of printers.

At the heart of the maritime economy- newspapers, posters, stock certificates, pamphlets, ephemera, invoices, menus, job postings, etc.- printers and their assistants worked day and night to support the waterfront. Through their creations the area prospered throughout the centuries.

“Butler & Kelley Engravers and Printers Trade Card” early 20th century. Gift of Peter Neill, 2000.001.0001

Print shops employed people of various backgrounds. Women could be found working less laborious positions such as editors, sales persons, or bookkeepers in shops run by male family members. Even if related to the printers, women would be paid less than men due to the belief men should be the main source of income for a family. Female printers were rare, often only taking over a printing business upon the death of a male family member[7] “Life in the old print shop,” by Bill Kovarik..

Print shops even provided free Black Americans a place to work. Newspapers created by Black citizens, “such as Freedom’s Journal, The Struggle, the Colored American, the militant Ram’s Horn, and in the 1850s, the Anglo-American, informed the Black public of abolitionist efforts and indicated local examples of discrimination”[8]”Black Society in Antebellum New York” by G. Hodges, published on Seaport Magazine, Summer 1989, pp. 20-25. Printing gave a voice and a vocation to people from everywhere. By 1900, New York City was home to over 700 print shops. In these stores, men and women printed news, images, stories, and business needs to support themselves and their communities.

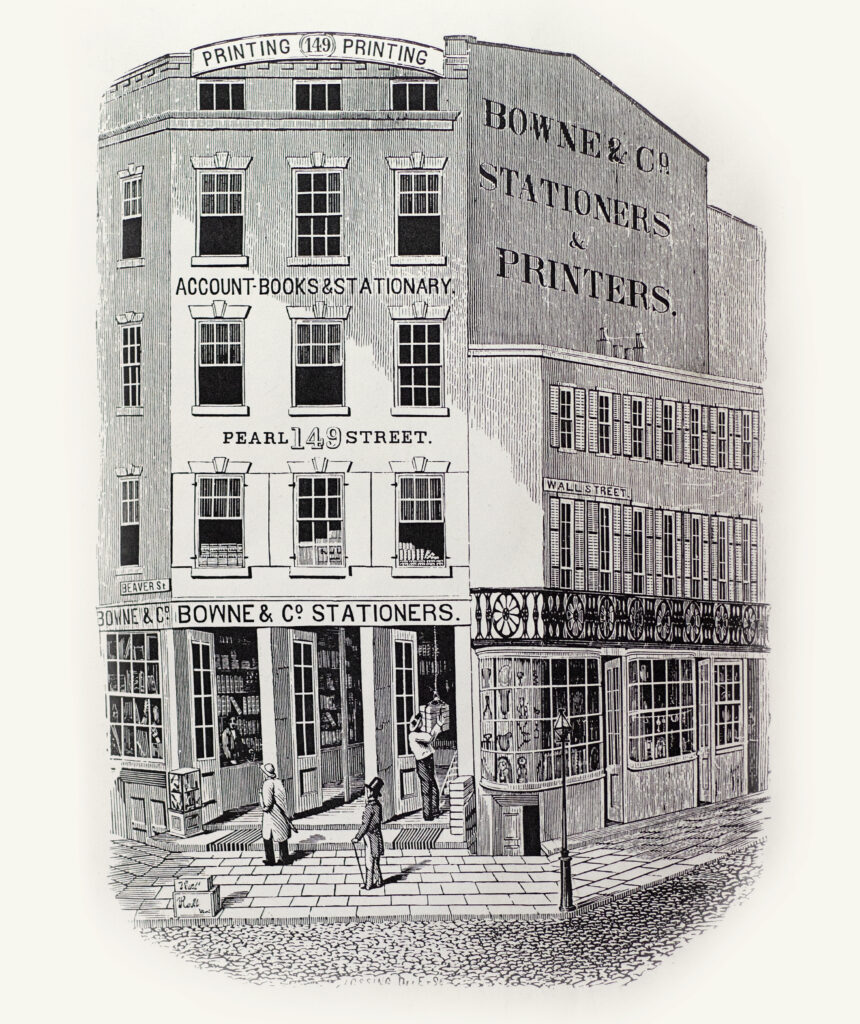

The seaport district is home to New York’s City’s oldest and largest printing firm, founded by Robert Bowne (1744-1818) in 1775. Owner Robert Bowne initially opened the doors as a dry goods and stationery store then later adapted his business to cater to the growing needs of the bustling business area.

Later, Bowne & Co. specialized in financial and commercial business work on an international scale. Celebrating its bicentennial, Bowne & Co. Inc. partnered with the Seaport Museum to offer museum visitors a chance to experience a live 19th-Century print shop, which the Museum continues to do to this day at the Printing Offices at Bowne & Co.

Learn more about what they do here.

Markets Vendors

If print shops are the heart of New York City’s port then the markets are the soul. Here, workers sold fish, fruits, vegetables, spices, herbs, and textiles to locals and visitors alike. Markets gave New Yorkers “the most diverse selection of foods available anywhere”[9] “The Seaport in 1883” by L. Shaw, published in Seaport Magazine, Summer 1983, pp. 9-16.

Along the stalls, people would exchange money, trade gossip, and integrate different cultures leading to a booming economic and social section of Lower Manhattan.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw women take on roles in which they looked after the home and children[10] “Women and Wok in Early America” by Jone Johnson Lewis, September 11, 2019. While men mainly worked hard laborious positions women were tasked with domestic labor such as sewing, washing, cleaning, and cooking to support their families. To do this many women worked at markets selling goods their families grew on a country farm, fish their husbands or sons caught earlier that morning, or clothing they sewed themselves.

“Thursday Morning at Fulton Fish Market” published in Harper’s Weekly on April 11, 1896. South Street Seaport Museum, 2005.025

Enslaved women also were made to work at the markets selling goods from the farms of their enslavers. Free Black Americans, especially women, also found the local markets to be a good way to earn money and to serve as “a primary vehicle for African culture”[11]”Black Society in Antebellum New York” by G. Hodges, published on Seaport Magazine, Summer 1989, pp. 20-25.

The seaport district has been home to one of the earliest open air markets in the country: The Fulton Fish Market. Shoppers flocked here during the week to purchase their meals and wares from the men and women working behind the various stalls. The first Fulton Market opened as a small fish market in 1807 in Lower Manhattan just off of Wall Street. In 1822, the market later moved to a neoclassical building on South Street to accommodate the growth of stalls selling different foods and goods.

In 1939, the New Building opened due to age-related destruction of its original building. At this new location, vendors rented stalls from the Port Authority of New York.

The Fulton Market stayed at its original location until 2005, when it was moved to the Bronx for extra space and modern cooling amenities. Markets will always be open to guests for commerce and socializing, but it is the people who work behind the stalls and counters that really make them thrive.

“Fulton Fish Market in session” n.d. (original ca. 1936). Gift of Vincent J. Tatick, Joseph H. Carter, Inc., 1997.006.0008

Lodging Owners and Domestic Labor

Hotels and boarding houses were a staple amongst the waterfront businesses. Sailors needed a place to rest between voyages, stevedores needed a place to stay hoping to find work along the docks, and many others simply relied on these locations for cheaper or temporary living arrangements. Not only did hotels and boarding houses allow people a place to stay, but also for many a place to work. Behind the scenes, men and women worked together to keep guests comfortable and fed.

At the turn of the 20th Century, many women sought out work in these locations as waitresses. Although the wages were lower than what their male counterparts made, women moving to a new city sought out these positions for the working conditions were considered better than factory-work.

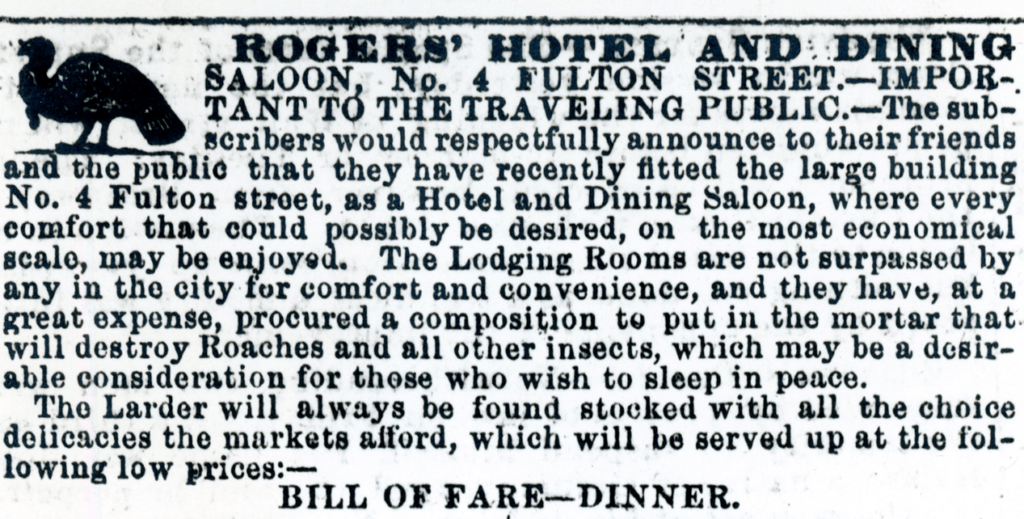

Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Bill of Fare, ca. 1860s. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

As the 19th and 20th centuries progressed urbanization pushed many newcomers to the city to rent rooms in boarding houses while looking for work. Some women took this as an opportunity to run their own business and use the skills they were raised with- cleaning, cooking, and general housekeeping- to cater to the bustling economy along the Port of New York.

The seaport district has been home to many hotels and boarding houses over the years. The Meyer’s Hotel and Boarding House on South Street at Peck Slip, built in 1873 initially as a combination of stores and lofts, and converted into a hotel by Henry L. Meyer in 1883, welcomed famous guests such as Annie Oakley, Thomas Edison, and Teddy Roosevelt (while he was head of the New York City Police Department).[12] “MEYER’S HOTEL, SOUTH STREET SEAPORT” by Joe Schiaffino, Forgotten New York, July 7, 2014.

There are also the Seaport Museum’s own hotels: the Fulton Ferry Hotel and the Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon. Opened in 1875 and 1850 respectively, these hotels stood on Schermerhorn Row giving workers and those seeking work a place to rest and recuperate between jobs until the early 20th century.

Divers

Below the surface of the Hudson, the East River, and New York Bay are people who are working behind the scenes to keep the maritime economy afloat- literally.

Freedivers have been exploring beneath the waters since ancient times by freediving- going beneath the water without the aid of a breathing apparatus. With the invention of individual diving suits in the 17th century and improvements made upon them in the early 18th century, divers have been used along ports around the world to aid in ship husbandry, salvaging, and collecting sea food.

Men who took on diving jobs needed to be knowledgeable in ship repairs, able-bodied enough to stay underwater for long periods, and confident in their abilities as well as their tools to work with limited light. The use of divers has allowed ships to decrease or even prevent the need for dry-docking, which is an economic drain for most ships.[13] “Underwater Ship Husbandry Program Mission” U.S. Navy.

Commercial diving has opened the doors for engineering, marine exploration, and general upkeep of both ships and the docks they pull into. Although divers work out of sight their impact on the Port of New York and its structures have been appreciated by everyone on shore.

“New York Harbor salvage diver” ca. 1910. Wendell Lorang Maritime Postcard Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

The Port of New York

New York City would not have been able to grow into what it is today without its coastline. An economic and cultural center, the city was founded upon its shores and grew inland. Without the original workers who risked life and limb, who were available at all hours of the day, and who provided rest and warm meals for locals and visitors the Port of New York would not have been the thriving success and boon to the economies of the city, region, and nation that it became.

In the Summer of 2020 the museum installed an outdoor exhibition on Pier 16 where you can learn more about some of the people and concepts written about here, be sure to stop by if you’re in the neighborhood.

And finally, I wanted to thank the workers who made the seaport district so special, and who helped mold New York City into the powerhouse it is today.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | “Blacks on the New York Waterfront During the American Revolution” by Charles R. Foy, 2016 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | THE LONGSHOREMAN. (1916). Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2(5), 1-7. Retrieved August 31, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41822971 |

| ↑3 | “The Black Man and the Sea” by S. Canright, published on South Street Reporter, Vol. VII, Winter 1973-1974, pp. 5-10 |

| ↑4 | “Women in New York City’s Maritime History” by Anna B. Baaske-Rodriguez, Mar 12, 2013 |

| ↑5 | “Saved from the Wrecker’s Ball,” by E. Fletcher, published on Seaport Magazine, Summer 1983, pp. 31-38 |

| ↑6 | “Baker, Carver & Morrell” by E. Rosebrock, published on South Street Reporter, Vol. IX, Summer 1975, p. 11 |

| ↑7 | “Life in the old print shop,” by Bill Kovarik. |

| ↑8, ↑11 | ”Black Society in Antebellum New York” by G. Hodges, published on Seaport Magazine, Summer 1989, pp. 20-25 |

| ↑9 | “The Seaport in 1883” by L. Shaw, published in Seaport Magazine, Summer 1983, pp. 9-16 |

| ↑10 | “Women and Wok in Early America” by Jone Johnson Lewis, September 11, 2019 |

| ↑12 | “MEYER’S HOTEL, SOUTH STREET SEAPORT” by Joe Schiaffino, Forgotten New York, July 7, 2014. |

| ↑13 | “Underwater Ship Husbandry Program Mission” U.S. Navy. |