Preserving skills through object reproduction

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

September 17, 2020

Have you ever wondered how a museum exhibition goes from an idea to an installation that you can visit and enjoy? There are a million decisions that are made by a museum’s exhibition team as they work on an upcoming show. Some decisions are big (should we include this 9 foot tall figurehead in the display?) and some decisions seem small (should we include the dimensions in the object label so people can learn the figurehead is 9 feet tall?), but every exhibition choice is an opportunity to find new ways to surprise, inform, and engage with visitors.

For this blog post I wanted to pull back the curtain a bit, and write about one of my favorite exhibition choices from Millions: Migrants and Millionaires aboard the Great Liners, 1900–1914, which opened at the Museum in June 2017. At the time we had the opportunity to not only create a reproduction of a rare fragment of a pre-World War I luxury liner, but to do it in a way that was ‘uniquely Seaport Museum.’

Millions examined, side-by-side, the differences between passengers in First Class and Third Class aboard ocean liners in the early 20th century. On each voyage, these massive ships transported thousands of people; passengers in First Class sailed across the Atlantic in the lap of luxury while passengers in Third Class made the voyage in the lower decks. From 1900 to 1914, nearly 13 million immigrants traveling in Third Class arrived in the United States, with most traveling through Ellis Island and the Port of New York. On the same ocean liners, America’s wealthiest citizens, totaling no more than a hundred thousand passengers each year, traveled to Europe in First Class, spending over $11.5 billion (2017) on luxury vacations. Even though First Class and Third Class sailed on the same vessels, their journeys were worlds apart.

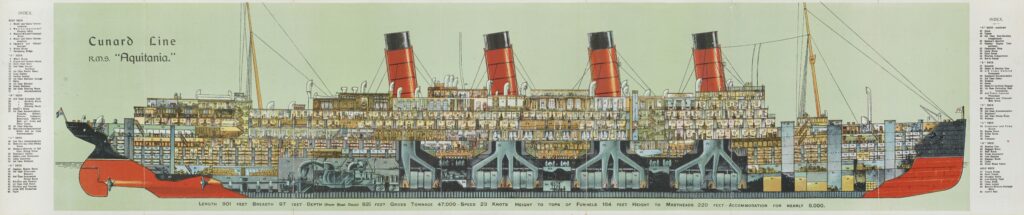

As the exhibit title Millions suggests, there were some big ideas we wanted to put into our small mezzanine gallery. We had to get creative to (metaphorically) fit ships the size of RMS Titanic into the Museum!

Cutaway of RMS Aquitania, 1913. Der Scutt Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 2001.028.0009

As the Collections and Curatorial Assistant, my work for Millions started with digging through the collections and archives to see what items could be included in the show. There were a lot of amazing options! The South Street Seaport Museum’s collections consist of over 28,000 works of art and artifacts, and over 55,000 historic records. As a whole, the collection documents the rise of New York as a port city, and its role in the development of the culture, economy, and business of the United States.

Before airplanes became the regular mode of travel between continents, ocean liners (defined as a ship that runs a regular schedule on an ocean-going route) were how most people travelled internationally. The concept of an ocean liner was actually developed in what would become the South Street Seaport Historic District in 1818 by the Black Ball Line. Prior to this innovation, a ship would depart whenever its captain determined it would be most profitable.

Unsurprisingly then, the Museum’s collections include thousands of ocean liner-related artifacts and approximately one third of our holdings are tied to ocean liners. Even when I narrowed my search to the years 1900-1914 and objects that reflected First- and Third-Class travel, I still had a list of several hundred items available, and I prepared lists for the exhibition team to make some of the aforementioned big decisions.

But who was the exhibition team? Every museum is unique; shows can be managed entirely by a single curator and some exhibits are designed by contracted design companies. For Millions the core team members were all Museum staff. Led by our Executive Director, the team consisted of the Museum’s historian, three collections management staff members (including myself,) and two designers from our Bowne & Co. letterpress print shop. Every member of the exhibition team brought a unique viewpoint to the table when looking at potential objects.

The Museum’s historian brought the narrative and ocean liner expertise, the collection management team knew the specific histories and preservation needs of the objects, and the designers knew how things can be aesthetically displayed, mounted and integrated into a cohesive whole. After all, an exhibition gallery is an interpretation of history built as a 3-dimensional space visitors walk into and interact with. For example, visitors to the Millions exhibit might not have known off-hand that the yellow wall color referred to the funnels of ocean liners like SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, or that the font used for the wall text was pulled from the Museum’s collection of 19th- and early 20th-century wood type at Bowne & Co. However, all of these subtle design and interpretation decisions are how an exhibition becomes an experience for the people who step through the door.

Choosing between the hundreds of fascinating objects that could have been included in Millions wasn’t easy. Along with the paramount concerns of interpretation and visitor experience, our choices had to take into account the composition of the collections items themselves. The collections management staff had to look at each object and decide whether or not putting them on display could put them in harm’s way! The space used for the exhibit is called the “mezzanine gallery”; it is located in an old seaport building and, along with having a unique layout, lacks the climate control of purpose-built museum galleries, as it was not a space deemed and planned to display artifacts. We had to work with unique facilities and environmental conditions, and find a balance between object care and display. Temperature and humidity fluctuations, light levels, and even the vibrations caused by passing footsteps can cause accumulating damage to artifacts so we had to choose objects that could safely acclimate to the space, or plan for alternative solutions.

Though there were some objects that couldn’t be displayed at all due to size and climate concerns (like a large canvas Cunard Line gangway cover), we included many items as reproductions. The majority of paper-based objects, like ocean liner posters, menus, and postcards, were reproduced on the wall as vinyl prints. We filmed the collections management staff opening the many compartments of a beautiful First-Class steamer trunk that was too delicate to display. With the “performance” of the First-Class trunk on view, visitors could compare it to the plain wooden box used by an immigrant traveling in Third-Class that was installed in the gallery.

Above left: Seaport Museum staff filming a NeverBreak Steamer Trunk, made by L. Goldsmith and Son, in ca. 1910. Gift of Carol M. Long, South Street Seaport Museum 2004.018

Above right: Emigrant trunk, ca. 1925. Gift of William Asadorian, South Street Seaport Museum 2002.034

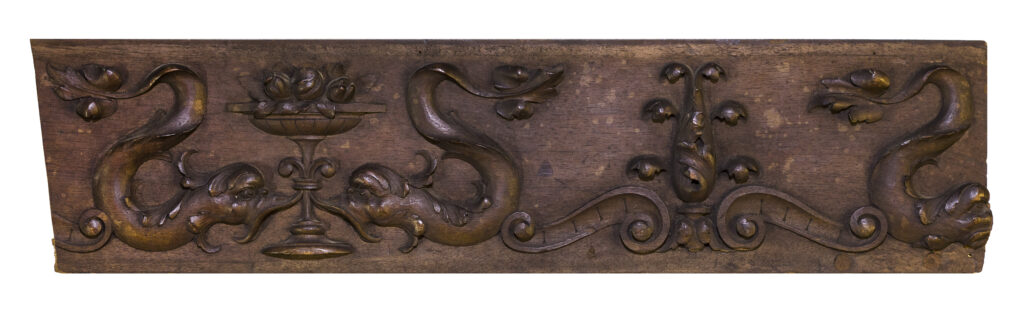

One object that the whole team wanted to include— but posed some unique problems— was a surviving decorative wood panel from the Cunard Line ship RMS Mauretania.

Mauretania was launched in 1906 and at the time was the largest moving structure built by human hands, measuring 790 feet long and 88 feet wide. The ship was designed to carry up to 2,165 passengers and 800 crew, with 563 berths in First Class, 464 in Second Class, and 1,138 in Third Class. Though Third Class accounted for the largest number of passengers on board Mauretania, like most ocean liners from 1900-1914 nearly two-thirds of passenger space was granted to First Class.

Shipping companies were in constant competition to attract the wealthiest customers, and the amenities offered in First Class rivaled the finest hotels. Compared to the two or three common rooms in Third Class, passengers in First-Class on ships like Mauretania might have access to a dining saloon, grill room, restaurant, tea garden, veranda café, ladies’ sitting rooms, palm garden, writing room, library, lounges, lobbies, smoking rooms, and on some liners a ballroom. Some luxury liners included a department store, beauty salon, barber shop, Turkish baths, swimming pool, tennis court, and even a greenhouse providing fresh flowers daily. The interiors of these rooms were inspired by the royal palaces of Europe and were decorated using the finest materials and the best artisans.

RMS Mauretania Passenger List, September 26, 1922. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation Collection 2006.029.0543

The panel in the Museum’s collection is from Mauretania’s First-Class smoking room, which was decorated in Queen Anne style, with Italian walnut paneling and Italian red furnishings. The original placement of the carved panels can be seen in this 1920s postcard of the smoking room.

None of these lavish pre-World War I ocean liners are preserved today. If they didn’t encounter a disaster (in some cases “surviving” as an underwater wreck) these ships were eventually retired and scrapped at the end of their careers, like Mauretania was in 1935. Only fragments of their physical fabric remain, if anything at all. Knowing we could share a tangible example of First-Class opulence, which otherwise we could only show in photographs and illustrations, was an opportunity the exhibition team didn’t want to pass up for Millions.

But the original piece of the Mauretania was a bad fit for the gallery! The artifact was on the list of objects that couldn’t be physically installed, so the exhibit team brainstormed how it could be presented. The panel could have been filmed like the First-Class trunk, but it didn’t have moving parts (clasps, drawers, clothes hangers) that made the trunk “performance” interesting to watch. There were also concerns about overloading visitors with screens. Printing an image of the panel wouldn’t have captured the quality of the carving.

RMS Mauretania Wood Panel, ca. 1907, by Harold Ainsworth Peto (1854-1933). Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation Collection 2006.029.0074

If we were going to include this original panel in Millions, we needed a 3-D reproduction. This would be something that visitors could touch, which the Museum educators had asked for as an important element for tactile learners. If I were writing from a different museum, this might be where I describe the transformational impact of 3-D printing for exhibitions, and the fascinating process of digitizing 3-D collections objects; however, for Millions we had had the opportunity to do it in the “seaport way”, since we were in the unique position to preserve and showcase the skills that led to the creation of Mauretania’s interiors over a century ago. Allow me to introduce master woodcarver Deborah Mills.

Deborah Mills showing summer intern Josie Cotton how to carve, July 2017

Deborah Mills has been carving wood professionally since 1991, carving by hand with chisels and mallet in a process she says “has altered little over millennia”. Her work is wide-ranging, from restoration projects to new commissions while working with designers, architects, and museums. The South Street Seaport Museum had been on her radar for years since, in her own words, “there are so many parts of ships, of nautical history, that involve beautiful ship carvings of all kinds.” She had even visited the Museum’s Maritime Craft Center when it was manned by master woodcarver and longtime volunteer Sal Polisi. When she was asked if she was interested in volunteering for the Millions exhibition, Ms. Mills says she was convinced when she saw the Mauretania panel in the Museum’s collection storage; “I remember when you first took me upstairs to see the panels and it was a sealed deal—to realize that I could spend hours with this beautiful artifact.”

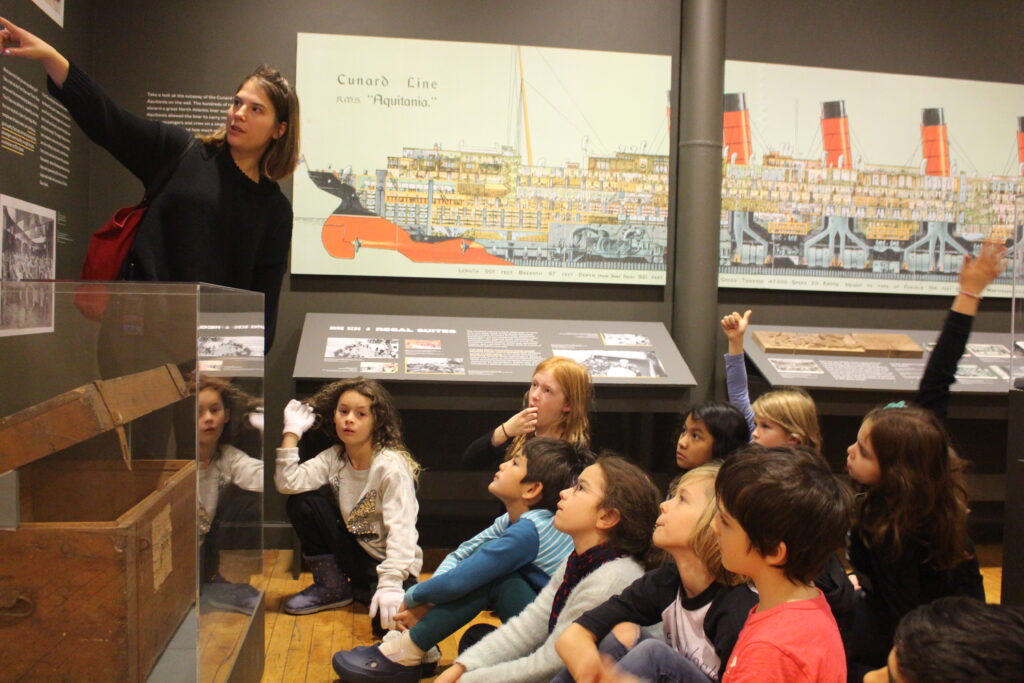

But for this exhibition we didn’t just want to display a static, completed reproduction of the panel; anyone could have done that. In order to share the tradition of maritime wood carving, Deborah Mills agreed to volunteer and make the copy at the Seaport Museum during visiting hours. Over the course of two years she was down at the Seaport Museum’s Maritime Craft Center one day a week to carve the piece live for visitors so they could watch as she brought the copy closer to the original!

When we interviewed Ms. Mills at the end of the two-year long project she described what it was like to carve in an open workshop; “It was very gratifying. I’ve been doing demonstrations for the public for 30 years because people don’t know how these things happen. They’ll assume it was done by machinery. People were excited to see people doing the work. Between myself and the printmakers [Bowne & Co.] next door, so many people don’t know the processes involved.”

She hammers home the Seaport Museum ethos, where we don’t just preserve the ships, artifacts and buildings, we preserve the skills that surround them.

How Ms. Mills describes sustaining the tradition of woodcarving could just as easily apply to maritime work or job printing: “It’s person to person. It’s like an ember that you are blowing on to keep it alive and then you pass that ember on to the next person. It’s the only way we are going to keep this knowledge as something that’s not just theoretical, or kept in a library.”

Having the Mauretania panel reproduced by a master woodcarver didn’t just add greatly to the Millions exhibit—it was also a chance to learn more about the object itself. In a collection of tens of thousands of objects, no museum staff member can dedicate the time studying a single object the way Ms. Mills could with the Mauretania panel.

The interview with Ms. Mills also serves to document what a master woodcarver noticed about this historic object. Between comments on style, tools and techniques, Ms. Mill’s expertise adds another layer of knowledge to the existing records of this 100 year old artifact.

When talking about the woodcarvers who worked on outfitting the ocean liner she said, “I was just gobsmacked at the mastery by the people who created it; it was decorative art but to me it was a true artist who created it…I wished a thousand times since I started this project that I could time travel and hover over the shoulders of the men who made it. I’m so curious. It [the segment of the ceiling molding in the Smoking Room of Mauretania] was 200 linear feet. This was production work and this was only one tiny molding element in a huge room full of beautiful architectural carving.”

Millions was a joy to work on as part of the Seaport Museum’s exhibition team. From the outset, the intention of Millions was to tell a crucial story of the Port of New York— of the time ocean liners simultaneously carried 13 million immigrants to America while also conveying the world’s most wealthy and powerful. However, when I spent those first weeks looking for every potential ocean liner artifact in the Museum’s holdings in 2017, I didn’t imagine that one object would lead to a two-year project underscoring the purpose of the Museum as a whole. What started as a creative solution to a quirky exhibition space became an example of what makes the Seaport Museum a special place— the merging of historic preservation with the intangible cultural heritage of traditional skills and craftsmanship.

Additional Reading and Resources

“Maury and the Menu: A Brief History of the Cunard Steamship Company” by Philip Sutton, New York Public Library, Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History & Genealogy, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, June 30, 2011.

“3D printing is quietly transforming an unexpected industry: museums” by Myrsini Samaroudi and Karina Rodriguez Echavarrial, Fast Company, April 4, 2019.

“You Can Now Download 1,700 Free 3-D Cultural Heritage Models” by Nadine Daher, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2, 2020.

Explore the Collections

Through the new and improved Collections Online Portal, you can explore highlights from the various collections within the Museum. Whether items are preserved in storage, displayed in Museum galleries, or on loan to fellow institutions, you can digitally discover some of these special objects in digital format.