A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

August 6, 2020

As we celebrate the 52nd anniversary of the arrival of the lightship Ambrose LV-87/WAL-512 to South Street on August 5th, 1968, as well as annual National Lighthouse Day, on August 7th, we couldn’t resist into looking in our archives and collections for a selection of items to help us celebrate the endurance of lighthouses and lightships in New York Harbor.

Some of these structures may be more recognizable than others, as you might see them while wandering in New York City, during a sail or ferry ride, or on your way to the beach. Others may be a bit more hidden, and less known. I hope that this quick overview will help you discover less familiar ones, as well as learn the incredible stories of their long-term caretakers, their restoration projects, and their continuing impact as icons of maritime heritage.

First and foremost, what is a lighthouse? And what is a lightship?

The United States Lighthouse Society defines a lighthouse as an enclosed tower with an enclosed lantern built by a governing authority as an aid to navigation. It defines a lightship as a ship, usually fitted with a light beacon on a tall mast that served as a lighthouse where it was not practical to build one.[1] United States Lighthouse Society, Lighthouse Glossary of Terms.

Lighthouses and lightships have always had two key roles: first, to warn of danger from a location that seafarers could see from distance, both night and day, and second, to safely guide vessels into ports, harbors or anchorages. These structures, on land or floating, were often placed in dramatic locations, and were maintained by dedicated keepers, often at great personal risk.

The history of lighthouses in America dates as far back as 1715, when the first lighthouse was constructed at the entrance of Boston harbor by the Province of Massachusetts. On August 7, 1789, an Act of Congress authorized the maintenance of lighthouses by the United States Government, and that is why this date is celebrated annually as National Lighthouse Day. The first U.S. “light boat” was launched in the summer of 1820 as an aid to the commerce of Chesapeake Bay. The first true American lightship, anchored in the open sea, entered service in 1823 off Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

The dramatic settings and the individual stories of each of these structures made them objects of great interest, but at the same time the advances in technology during the second half of the 20th century have made many obsolete. Luckily, the pressure to save these symbols of maritime heritage prompted the establishment of numerous lighthouse preservation organizations, and more recently, the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 which provides a mechanism for the “disposal” of Federally-owned historic light stations at no-cost by transferring these structures to nonprofit corporations, educational agencies, community development organizations, and federal, state, and local governments.

Romer Shoal Lighthouse

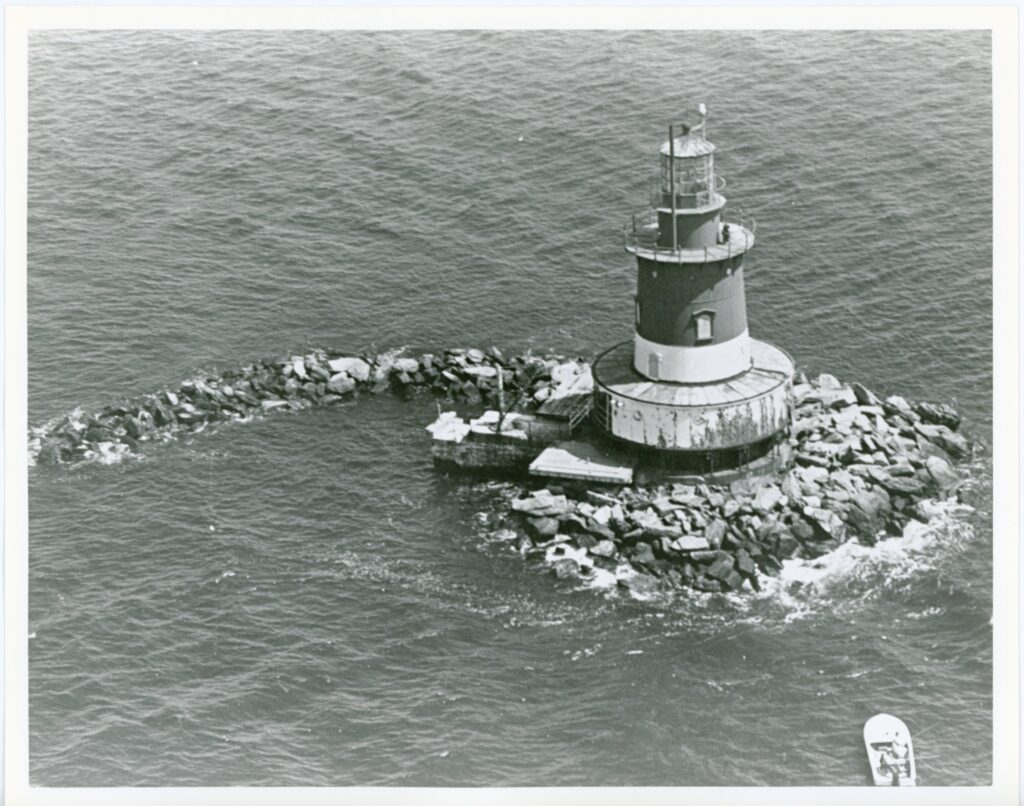

Romer Shoal Light is a National Historic Landmark located in Lower New York Harbor, 2 nautical miles (nm) south of Ambrose Channel and 3 nm north of Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

The shoal was named after Colonel Wolfgang William Romer, a well-known engineer who was asked by the governor of New York to sound the waters “between the city and the ocean” to ascertain ships approaching and defensive measures to protect the city.

The Colonel made an elaborate report in January of 1700 which is also the origin of many of the current names of New York Harbor’s geographical features.[2] The Historical Magazine, 1870, p. 230.

Romer Shoal Light, n.d. (original ca. 1960). South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive, H91-0035

Congress allocated $15,000 in 1837, and then another $10,000 in 1838, for the creation of a day-beacon to mark the shoal. Captain Winslow Lewis was chosen as the engineer to survey the area and select the site for the tower, but after construction had started two naval officers complained that the tower was being built in the wrong place. Work was allowed to continue, but mariners were warned not to “run for the beacon, or they would infallibly get on shore.”[3] “The American Coast Pilot: Containing Directions for the Principal Harbors …” by Edmund March Blunt, 19th Edition, 1863, p. 321. Still, the misplaced daymark did help mariners avoid the underlying shoal.

The structure has a tumultuous history, including a longer construction, and reports of impracticable landing due to severe weather, erosion of the shoal, and extensive needs of funding and attention. She was first lit on July 15, 1886, but was soon relocated on land to be a land-based training light at the National Lighthouse Keepers Academy on Staten island.

The present 54-foot lighthouse was established on the shoal in 1898. The lighthouse was automated in 1966, and it continued to help mark the entrance to the Harbor with a pair of white flashes every fifteen seconds. After a storm in December of 1992 damaged the lighthouse, the Coast Guard considered scrapping the lighthouse and replacing it with a steel skeleton tower, but a local beloved historian Joe Esposito(about whom we’ll learn more later in the blog!) refused to let the tower be destroyed, and through his ardent efforts it remains in place today.

The light was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007, and in 2011 was auctioned through the General Services Administration and purchased by a group of committed stewards. The mission and vision of this preservation group is to restore the historic structure and make it accessible to all, as well as to enable the United States Coast Guard to maintain this crucial aid to navigation. They also hope to create a land-based museum to share awareness and education programs around the history and ecology of the Lower New York Harbor. To learn more visit romershoal.org/.

Coney Island Lighthouse

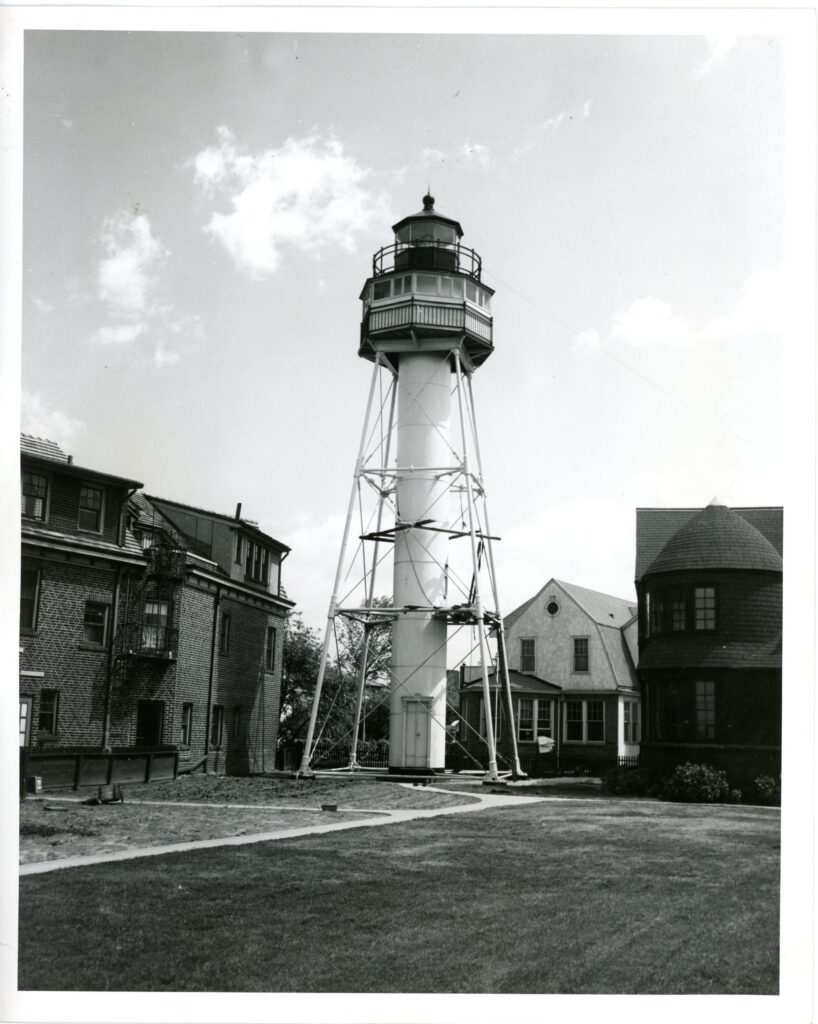

Located at the western end of Coney Island, in an area formerly known as Norton’s Point, the Coney Island Lighthouse has watched over Lower New York Bay since it was built in 1890.

Along with the original tower, which is composed of a white skeleton tower topped by a black watch room and light chamber, the site also has an adjoining keeper’s house and storage shed.

The light, 75 feet above sea level, is a fourth-order Fresnel lens; it flashes red every five seconds, and is visible for 16 miles. Additionally, this working lighthouse is also one of the Atlantic Coast’s special radio beacon stations for the calibration of ship’s directional signals.

The lighthouse is most famous for its dedicated keeper Frank P. Schubert. Mr. Schubert was America’s last civilian lighthouse keeper working for the Coast Guard, and he served at the Coney Island Lighthouse from 1960 until his death in 2003.[4] “Frank P. Schubert Dies at 88; Lighthouse Keeper Since 1939” by Robert D. McFadden. New York Times, December 13, 2003.

Coney Island Lighthouse, n.d. (original May 1945). South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive, H91-0024

Marie Shubert, Frank’s wife for more than 30 years, assisted her husband in his keeper duties, and in an interview released in 1975 she mentioned how there was nothing unusual about the arrangement. The old Lighthouse Board often appointed a keeper’s wife as his paid assistant, to be on the property 24 hours a day, seven day a week, and she felt lucky as they even had neighbors, unlike other more isolated locations![5] “The Last of the Lighthouse Mohicans” by Rebecca Morris. New York Sunday News, January 5, 1975. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

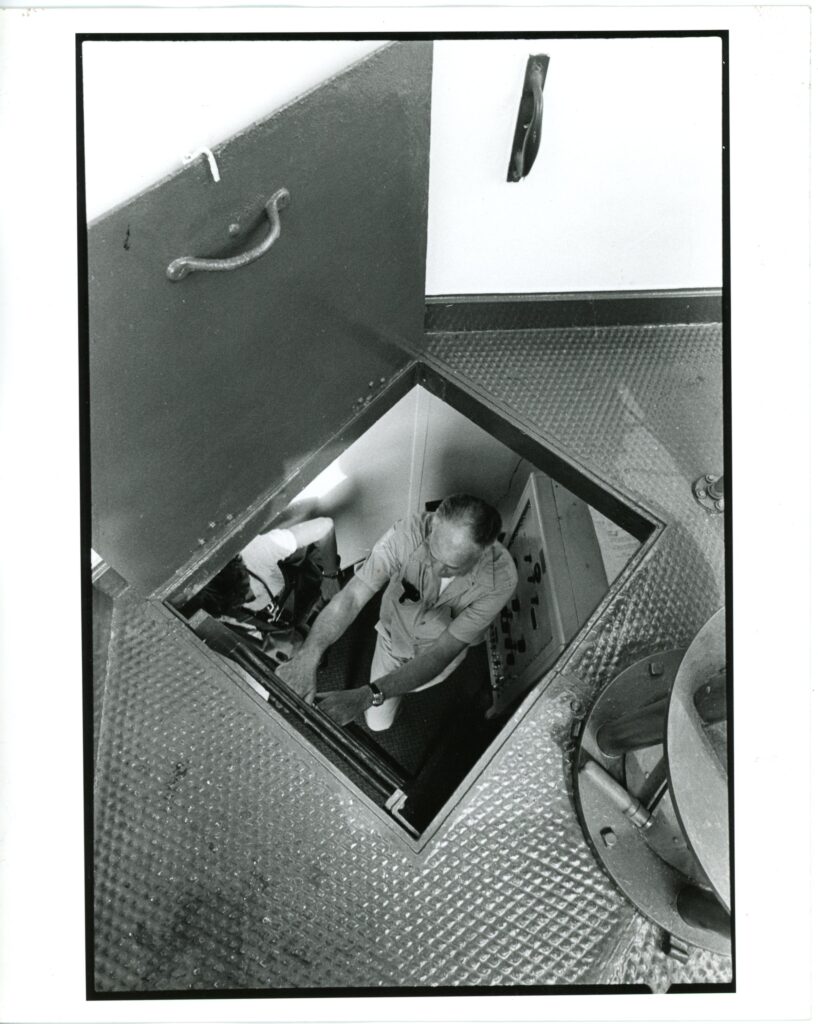

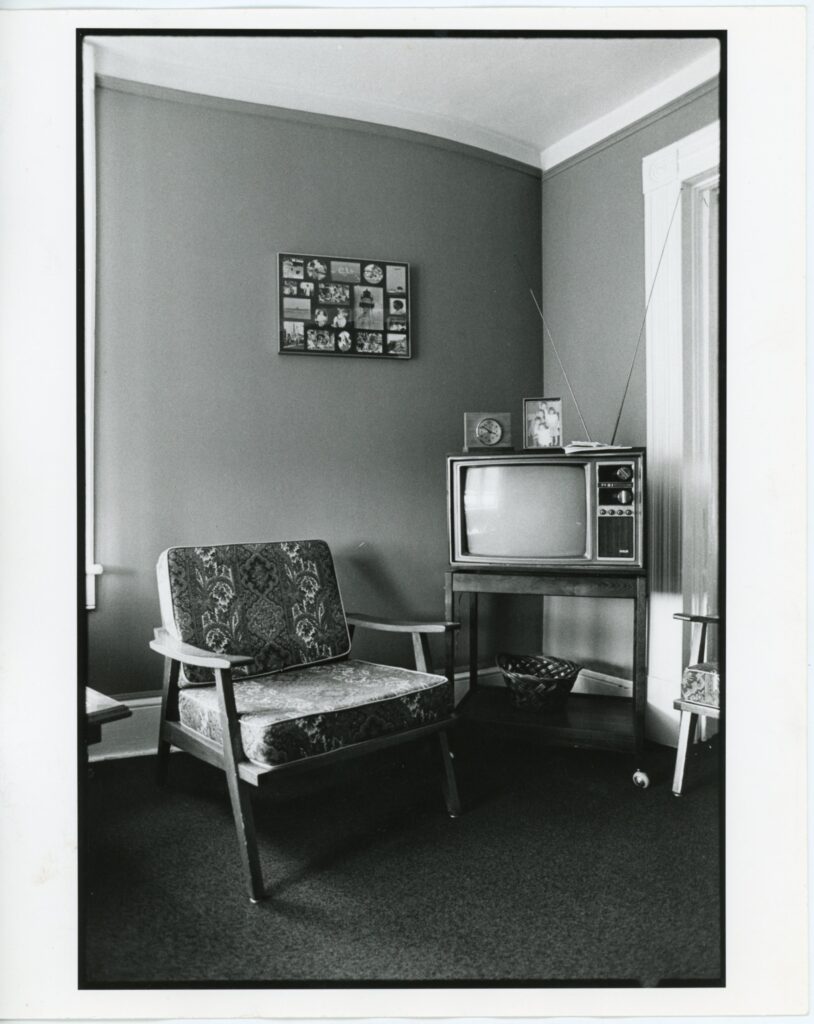

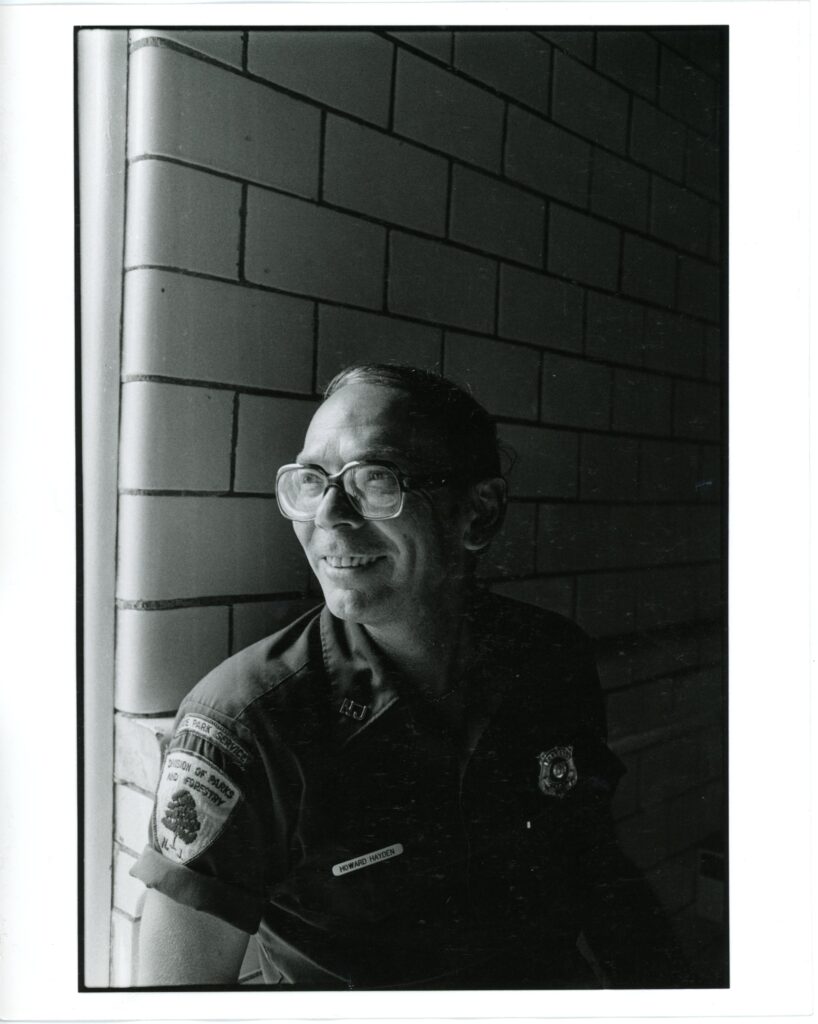

Photos by Alan Orling for Seaport Magazine, Summer/Spring 1982. South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H91-0027, H91-0032, and H91-0031

During the following decades Mr. Schubert was occasionally asked to give interviews or tours, including a photographic one given to Alan Orling for our Seaport Magazine, Summer/Spring issue in 1982, but it was in 2002 that his story became nationally famous when a national radio program found him.

In a charming interview with The New York Times published in April 2002 titled “So, It’s a Lighthouse. Now Leave Me Alone” he mentioned how the magnitude of attention of that year was inexplicable, and it was perhaps due to post-September 11 nostalgia for the old, simple days. He found a way to avoid reporters, filmmakers, and curiosity seekers with a perfect scheme of miscommunication of dates and times to contact him, and the Sea Gate Police Department, an armed force that patrols the area around the light, was left to deal with these individuals saying “He’s an old man with particular tastes. He just really likes to be left alone.”[6] “So, It’s a Lighthouse. Now Leave Me Alone.” by Charlie Leduff. New York Times, April 18, 2002.

Today, the Coney Island Lighthouse is still owned by the Coast Guard, while the cottage is leased to the Sea Gate Association. The light is an automated 150-watt bulb, but when it was first built it was fueled by kerosene by hand, and “Believe it or not, those kerosene lamps threw more light than these electric ones do now.”[7] “Shining Example. Lighthouse keeper honored for years of singular service” by Laura Italiano. New York Newsday, Saturday, July 1, 1995. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

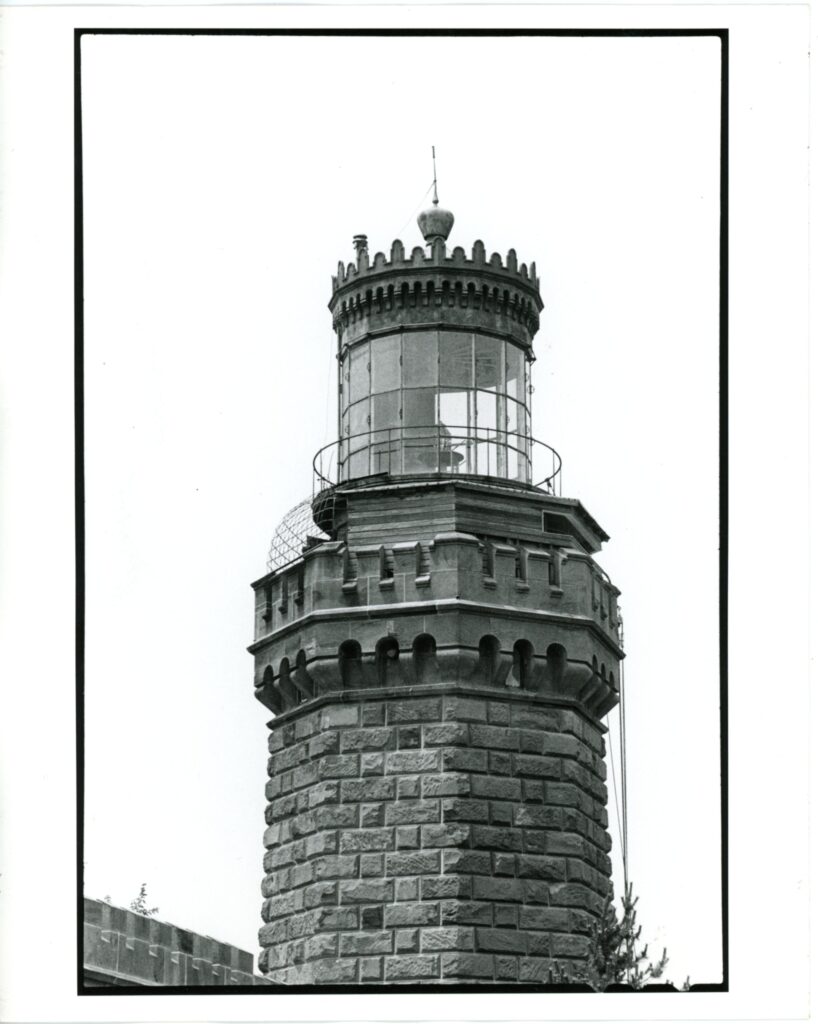

Staten Island Range Lighthouse

Located on Lighthouse Hill in Staten Island, in an idyllic neighborhood surrounded by Victorian turn-of-the century houses, the only Frank Lloyd Wright designed house in New York City, and the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, the Staten Island Range House lighthouse is an octagonal-shaped brick tower, with a rusticated limestone base, still in operation, manned by the Coast Guard.

Established in 1909, and first lit in 1912 with a kerosene lamp, the lighthouse aids ships entering the Ambrose Channel, between Staten Island and Brooklyn, on the opposite side of New York Harbor as the Coney Island lighthouse. In 1939 the lamp was updated with a 1,000 watt bulb and a Fresnel range lamp, and it’s now automated.

In 1968 the lighthouse was designated a National Historic Landmark and the designation report notes that in addition to its “distinguished” architecture that “one would expect to be on the rocky coast of New England than within the boundaries of New York City” the lighthouse “served for over fifty years guiding ships into one of the world’s busiest harbors and that it stands as a reminder of the men and women in the lighthouse service who have devoted their lives to the safe entry and departure of ships in and out of this great American port.”[8] Landmark Preservation Commission Designation Report, January 17, 1968.

The beloved local historian, Joseph N. Esposito (1938-2005), took care of the light from 1992 to 2001, accepting no salary in exchange for his labor until his health forced him to retire. Mr. Esposito was the founder of the Lighthouse Research for Preservation and New York Harbor Lights, helped save Romer Shoal and Battery Weed Lighthouses, and was instrumental in the founding of the National Lighthouse Museum on Staten Island in 1997. The Coast Guard recognized his service in a ceremony on April 18, 2001, during which Esposito was awarded a citation for his meritorious service.

The National Lighthouse Museum received stewardship of the lighthouse tower and yard in 2019 from the U.S. Coast Guard.

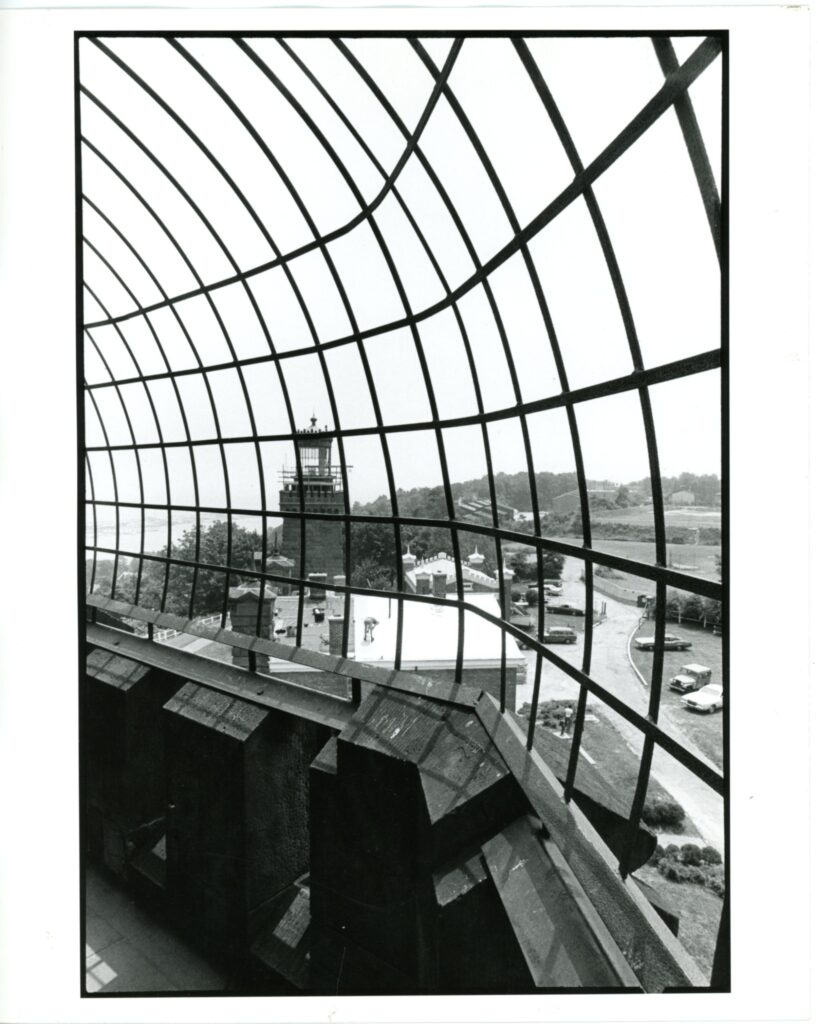

Navesink Twin Lights

The Navesink Light Station has been around since 1828. Today’s twin-towered structure was built in 1862 atop the 200-foot-tall Navesink Highlands, two miles south of the Sandy Hook Lighthouse.

Architect Joseph Lederle replaced the earlier buildings that had fallen into disrepair, and designed the new lighthouse with two non-identical towers linked by keepers’ quarters and storage rooms.

This unique design made it easy to distinguish Twin Lights from other nearby lighthouses.

Aerial view of Navesink Twin Lights, n.d. (original ca. 1950). South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H91-0003

Keeping the lights lit and in good order required a principal keeper and three assistants. Over the years, more than a dozen principal keepers and 70 assistants served at Twin Lights. Their primary duty was to maintain the light from sunset to sunrise, and to maintain the buildings and grounds, but at times the keepers’ lives were dangerous.

In January 1875, three assistant keepers requested that the night watch be divided into three shifts “…owing to the extreme dampness and cold existing in the Towers..” And a few years later, in 1883, a keeper accidentally set himself on fire while lighting the South Tower light.

Photos by Alan Orling for Seaport Magazine, Summer/Spring 1982. South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H91-0007, H91-0006, and H91-0009

The structure, besides being really fascinating on account of its brownstone construction, holds various firsts. In 1841 it was the first lighthouse to use the Fresnel lens: a first-order fixed light in the South Tower and a second-order revolving light in the North Tower.

Other firsts include the first set up of Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraph in 1899. Marconi’s first demonstration was reporting on the America’s Cup yacht races happening off the tip of Sandy Hook. This demonstration worked so well that he expanded his operations, making Twin Lights the nation’s first wireless telegraph station capable of sending and receiving messages on a regular commercial basis.

Then in 1935, Twin Lights was the place where the United States Army tested various electronic devices, including its Mystery Ray—now known as radar.

Today the Twin Lights site is owned and operated by the State of New Jersey, Department of Environmental Protection Parks & Forestry, and it’s open for tours thanks to the Twin Lights Historical Society.

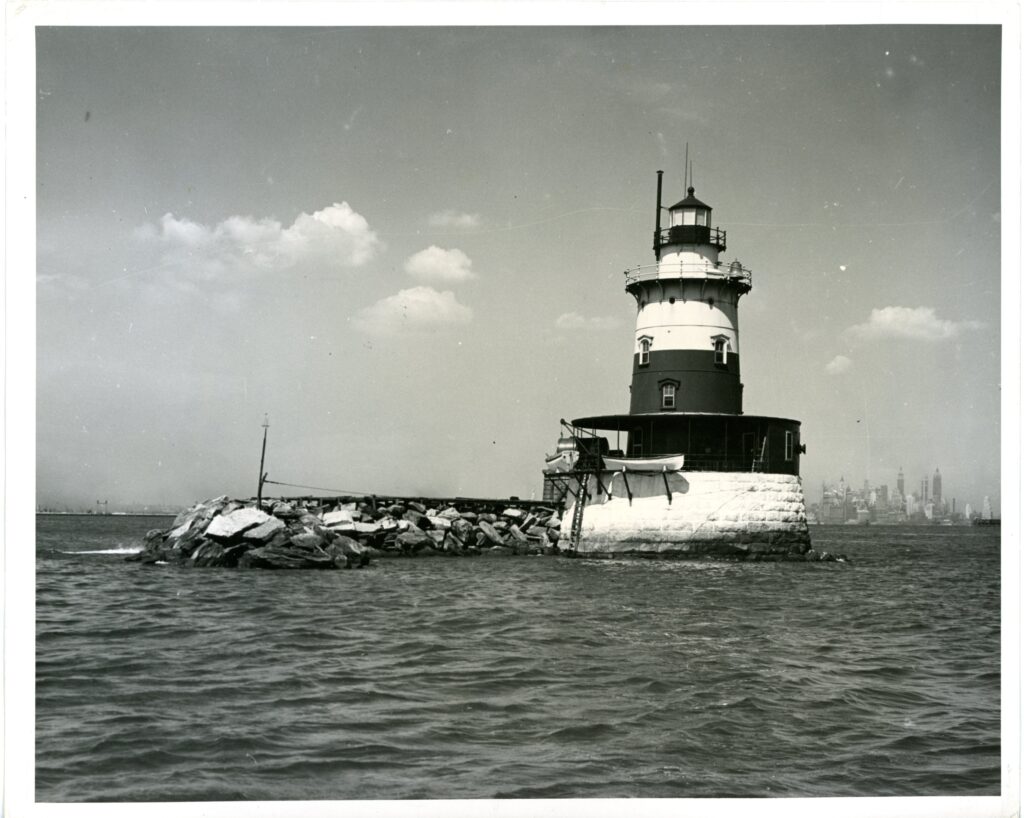

Robbins Reef Lighthouse

Robbins Reef Lighthouse was commissioned by the United States Congress in 1837 because the shallow water of New York Harbor was a danger to navigation.

The lighthouse may have been isolated out in the middle of New York Harbor, but its residents were not lonely. Among them, the most famous are the Walkers.

Robbins Reef Light, n.d. (original ca. 1950s). South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H91-0039

John Walker, a Swedish-born Civil War veteran, was transferred to the lighthouse at Robbins Reef in December 1885 with his newly-wed wife Kate Kaird, a former widow and single working mother from Germany. Kate worked as John’s official assistant, and when John died of bronchopneumonia in 1890 she wanted to take over his post. The federal government was wary of giving that job to a woman, but after offering the position to many men who declined it, in 1895 Kate was named official keeper after unofficially filling the role for five years.

Kate Walker’s home in the lighthouse was a place where family lived and friends gathered.

Kate’s granddaughter Lucille said that her “happiest time was when the whole family and many friends would come out to the lighthouse…there were always so many goodies they would bring out.” At low tide, the family also had their own private beach that extended out more than 100 feet and all of the grandchildren learned to swim there.

On February 28, 1919, Kate Walker retired from service at Robbins Reef Lighthouse. This decision was not by choice, but was the result of a new government mandate that required lighthouse keepers to retire by their 70th birthday; Kate was already 71. She moved to Tompkinsville, Staten Island, within walking distance of the waterfront, where she lived with her daughter Mae and was often surrounded by friends and family.

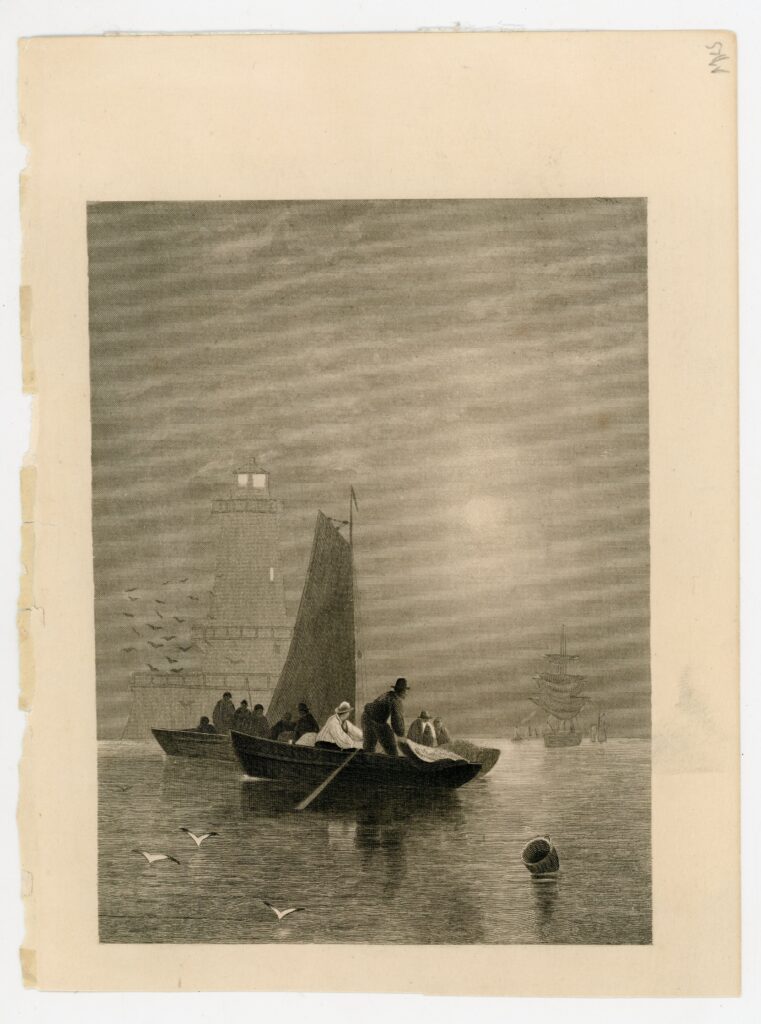

Robbins Reef N.Y. Harbor, n.d. (original ca. 1850). South Street Seaport Museum 2006.045.0011

In 1939, the Lighthouse Service was absorbed into the Coast Guard. Crews of two Coast Guardsmen and a civilian keeper worked together on a rotating basis to do the job Kate had done largely by herself. Since the mid-20th century the light has been automated. The US Coast Guard maintains the solar-powered light, which blinks every six seconds, and NOAA maintains the weather-data equipment.

The Noble Maritime Collection received stewardship of the lighthouse in 2011 and the volunteer Noble Crew has been actively restoring it as a museum. In the summer of 2019 they shot some footage of the lighthouse with a drone, that shows what the structure looks like now. To see the video and learn more visit the Noble Maritime Collection’s website.

Titanic Memorial Lighthouse

This lighthouse has a slightly different history, and meaning. The Titanic Memorial Lighthouse is a memorial to honor the passengers, officers, and crew who perished when the steamship RMS Titanic sank after collision with an iceberg.

It was originally erected on the roof of the Seamen’s Church Institute (SCI), 240 feet above sea level, at the corner of South Street and Coenties Slip (now Vietnam Veterans Plaza), on April 15, 1913.

It was built by public subscription after the group in attendance at the ceremony to celebrate laying the cornerstone of their new building at 25 South Street made a plan to build a lighthouse on top of the building to commemorate the heroism displayed by many in the tragedy, as well as remember those who lost their lives.

Building this lighthouse became a nationwide effort and many people donated to the cause, including wealthy socialites like Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, as well as school children who donated pennies and nickels.

From 1913 to 1967 the time ball at the top of the lighthouse would drop down the pole to signal twelve noon to the ships in the harbor.

This time ball mechanism was activated by a telegraphic signal from the National Observatory in Washington D.C. The time ball consisted of a bronze frame, four feet across covered with canvas that was painted black for maximum visibility, and it was put into operation November 1, 1913.

The lighthouse remained in its original location until 1968, when, after 55 years of service, SCI moved its headquarters to 15 State Street and the old building, along with the Lighthouse, was set to be demolished.

A group of concerned preservationists persuaded the demolition company to donate the lighthouse to the Seaport Museum. In a letter to the company, Museum founding president Peter Stanford wrote the following: “The Lighthouse atop the building was dedicated many years ago, when new, to the victims of the Titanic disaster. We believe this monument should not be doomed as part of the obsolete building to which it happens to be attached. The tragedy of the Titanic, and its lessons to history, are not less real today than in 1912…It would dishonor the memory of the victims by destroying the monument within the lifetimes of those who remember.”

The tower was donated to the South Street Street Seaport Museum by the Kaiser-Nelson Steel and Salvage Corporation in July of 1968, and it was erected in her current location in May 1976 with funds provided by the Exxon Corporation.

Today the structure anchors a small park at the intersection of Fulton and Water streets, at the entrance of the South Street Seaport Historic Seaport District. It is a visible welcome to the seaport district, providing a space for people to stop and reflect on Titanic’s tragic story, and its impact on Lower Manhattan over one hundred years ago.

Lightship Ambrose

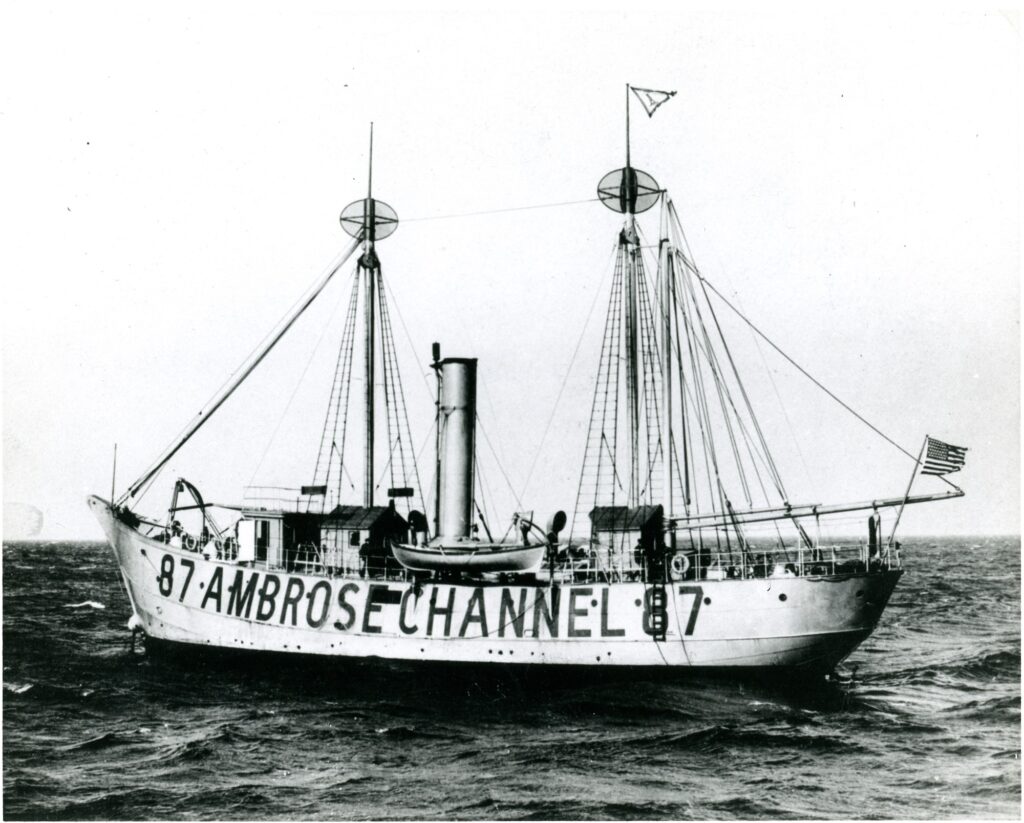

Lightship LV-87/WAL-512, also known as Ambrose, was built in 1907 as a floating lighthouse to guide ships safely from the Atlantic Ocean into the broad mouth of lower New York Bay between Coney Island, NY, and Sandy Hook, NJ–an area filled with sand bars and shoals perilous to approaching vessels.

Lightship Ambrose LV-87/WAL-512 at her station, ca. 1910. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

From 1908 until 1932 she marked the entrance to the Ambrose Channel, a deeper channel dredged in the early 20th century to allow larger ocean liners safe access into New York Harbor. Both the ship and the channel are named for John Wolfe Ambrose, who immigrated to the U.S. from Ireland as a boy, and grew up to be a brilliant engineer and developer. It was because of his efforts, that the channel was dredged, deepening it to handle the largest transatlantic ships, which in turn allowed New York’s commercial economy to boom and helped usher in the greatest period of immigration in US history.

In this latter role, lightship Ambrose served a very real function for the millions of immigrants who would go on to pass her on their journey into New York Harbor. In addition to being the first indication that they were arriving in America, Ambrose was also the finish line in a great race to get into New York ahead of closing quotas limiting immigration. In this respect, the light at Ambrose’s masthead is as significant a symbol of liberty as the light in the torch of Lady Liberty herself. Indeed, Ambrose, paired with that iconic statue, represents the very front door of New York to the world and was for decades a welcoming sight for hopeful travelers arriving at New York. In 1921 Ambrose became the first lightship to be fitted with a radio beacon, greatly increasing her ability to assist ships navigating the channel in poor visibility.

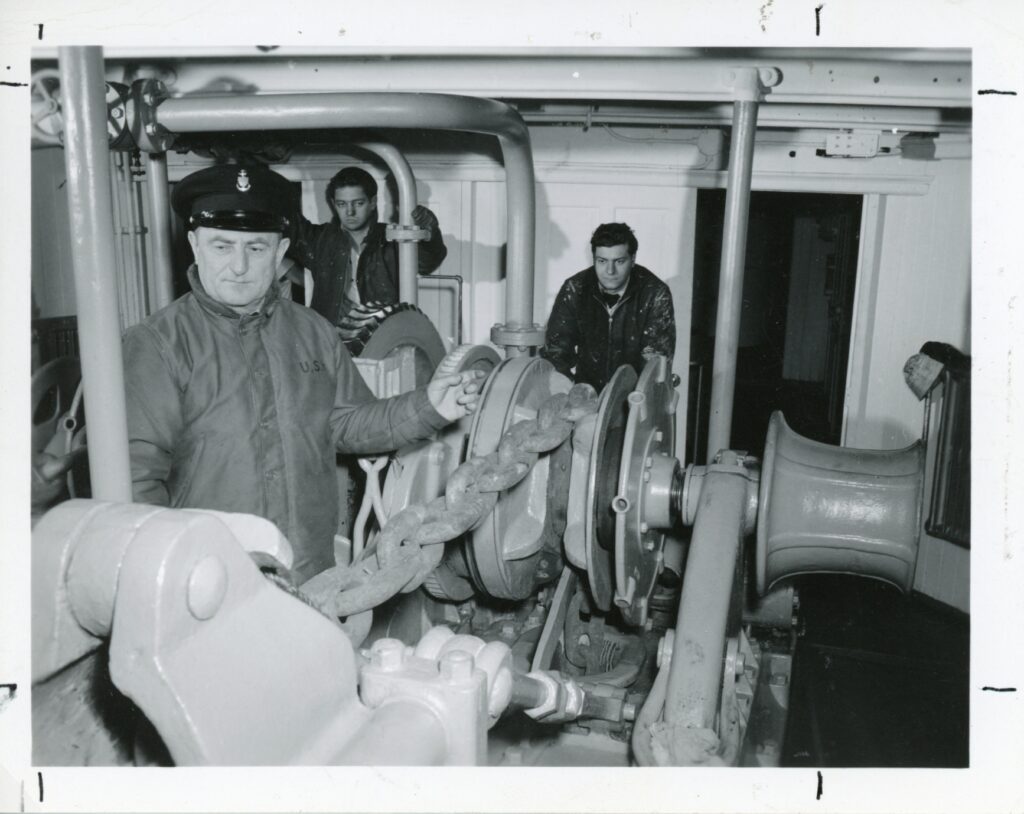

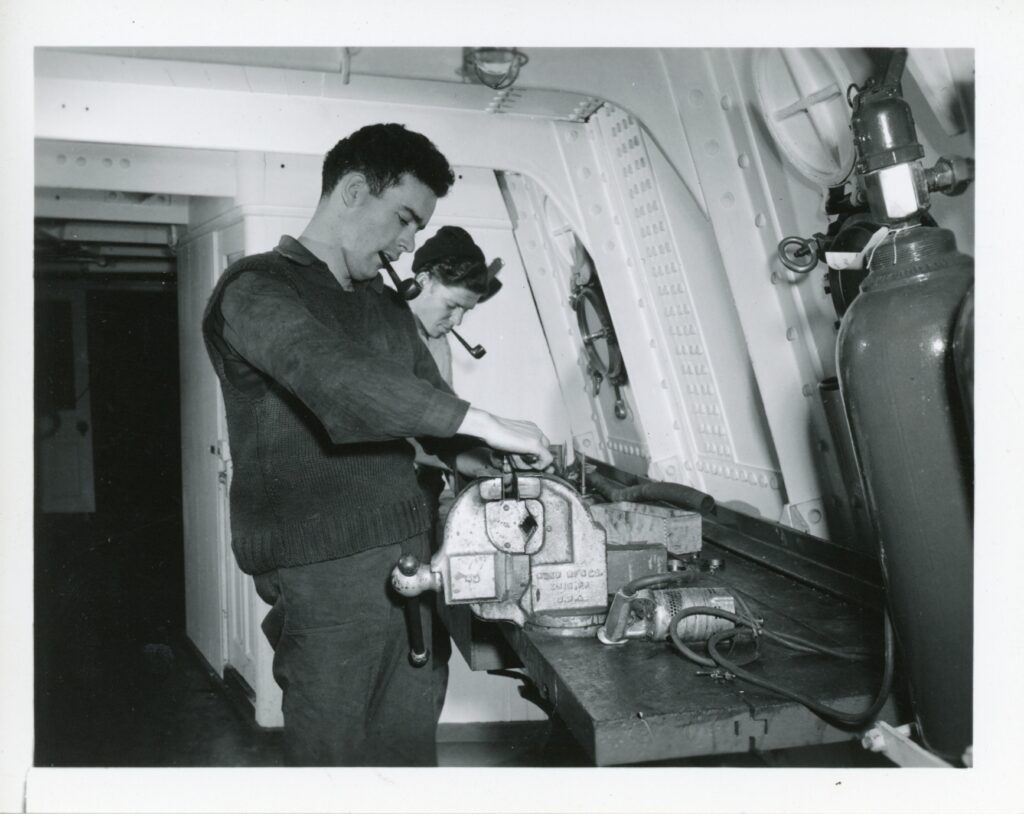

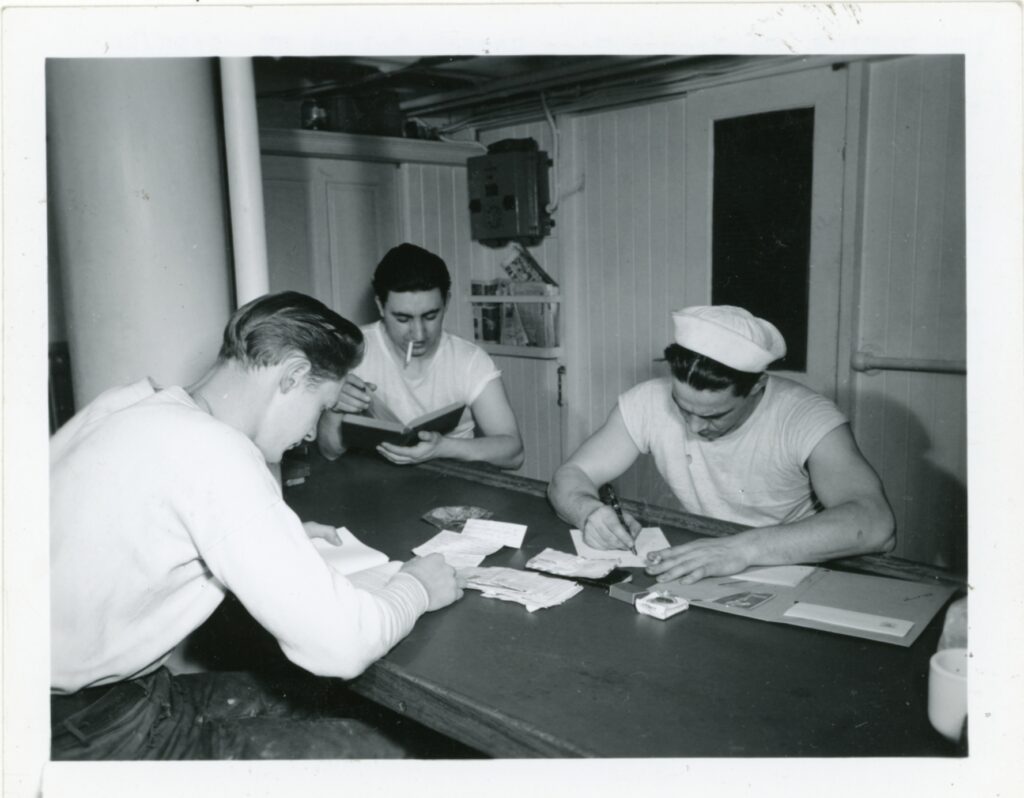

Being a lightship keeper wasn’t an easy, rewarding, or melancholic isolated job. The team on board was composed of approximately 15 crew members, including the captain, and in the early days they spent eight months of the year at sea, with two to four months on shore leave.

Ambrose‘s Staten Island Base Crew, 1945. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Many recollections of captains from the mid-19th century talk about how these vessels were constantly in motion, constantly rolling and pitching at the fury of the sea, causing damage to lanterns, and to the sailors’ compartments.

Later on, lightships improved their hull design, engines, and ballasts to produce more stable vessels, as well as improve the crew’s comfort, thanks to radios, and later tvs, and the length of a shift on board was cut to 30 days at time.

After her half-century career, on August 5, 1968, she was donated to the newly-formed South Street Seaport Museum by the U.S. Coast Guard, making her the first historic vessel to join our fleet.

New York Harbor is home to many lighthouses and light-vessels which, over the years, have guided countless ships into port. I can’t imagine what it would have been like seeing transatlantic liners passing by each one of these small lights, especially in the evening, when these great liners were all lit up like floating cities!

The more I researched the stories of each of these remarkable structures, the more I realized that, beyond their unique architectural features and historic significance, each one of them has at its heart a powerful human story of life, bravery, immigration, feats of engineering, and above all, resiliency.

Suggested readings:

A History of U.S. Lighthouses, by Willard Flynt, 1993.

Fleming, Candace. Women of the lights. Morton Grove, IL, A. Whitman, 1996.

Lighthouses of the world. Compiled by the International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities. Old Saybrook, CT, Globe Pequot Press, 1998.

Crompton, Samuel Willard. The ultimate book of lighthouses: history, legend, lore, design, technology, romance. San Diego, CA, Thunder Bay Press, 2000.

Jones, Ray. The lighthouse encyclopedia: the definitive reference. 2nd ed. Guilford, Conn., Globe Pequot Press, 2013.

Lighthouses (National Park Service) – Lighthouses to visit listed by state and region

United States Lighthouse Society – The society is a non-profit historical and educational organization incorporated to educate, inform, and entertain those who are interested in America’s lighthouses, past and present, including an interesting list of fun facts.

Lighthouse Postcards (Smithsonian National Museum of American History) – This online collection showcases the lighthouse postcards in the Engineering Collections at the Smithsonian. It includes digitized images of 272 postcards, general information on the US and Canadian lighthouses represented in the collection, and customized nautical charts provided by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

National Lighthouse Museum – Located on the former site of the United States Lighthouse Service’s (USLHS) General Depot in St. George, Staten Island, the National Lighthouse Museum educates visitors about the history and technology of the nation’s lighthouses.

References

| ↑1 | United States Lighthouse Society, Lighthouse Glossary of Terms. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Historical Magazine, 1870, p. 230. |

| ↑3 | “The American Coast Pilot: Containing Directions for the Principal Harbors …” by Edmund March Blunt, 19th Edition, 1863, p. 321. |

| ↑4 | “Frank P. Schubert Dies at 88; Lighthouse Keeper Since 1939” by Robert D. McFadden. New York Times, December 13, 2003. |

| ↑5 | “The Last of the Lighthouse Mohicans” by Rebecca Morris. New York Sunday News, January 5, 1975. South Street Seaport Museum Archives. |

| ↑6 | “So, It’s a Lighthouse. Now Leave Me Alone.” by Charlie Leduff. New York Times, April 18, 2002. |

| ↑7 | “Shining Example. Lighthouse keeper honored for years of singular service” by Laura Italiano. New York Newsday, Saturday, July 1, 1995. South Street Seaport Museum Archives. |

| ↑8 | Landmark Preservation Commission Designation Report, January 17, 1968. |