Language, Clubs, and Hidden Histories in the Archival Collections

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Elena Abou Mrad, Archives and Special Collections Specialist

and Elizabeth (Lizzie) Shack, Collections and Exhibitions Management Intern

May 8, 2025

Almost a year ago, while looking into the Dutch Stove Scrapbook from the Miller Family Beefsteak Dinner Collection, the Seaport Museum’s Director of Collections and Exhibitions, Martina Caruso, pointed out a newspaper clipping titled “Queer Clubs of New York.” This sparked so many questions: Why were these clubs referred to as “queer?” Was the article using the term in a pejorative sense? Would any of these clubs be considered queer, in the modern sense of the word?[1]See the definition of “queer” as it’s used today, from The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center: “An adjective used by some people whose sexual … Continue reading And most of all, when did people even start using this term?

We decided to look into learning more about the “Queer Clubs” that the article was talking about, which led us to explore the history of the word and, subsequently, into the Museum’s Archival Collections, to find out if there were more connections than we initially thought.

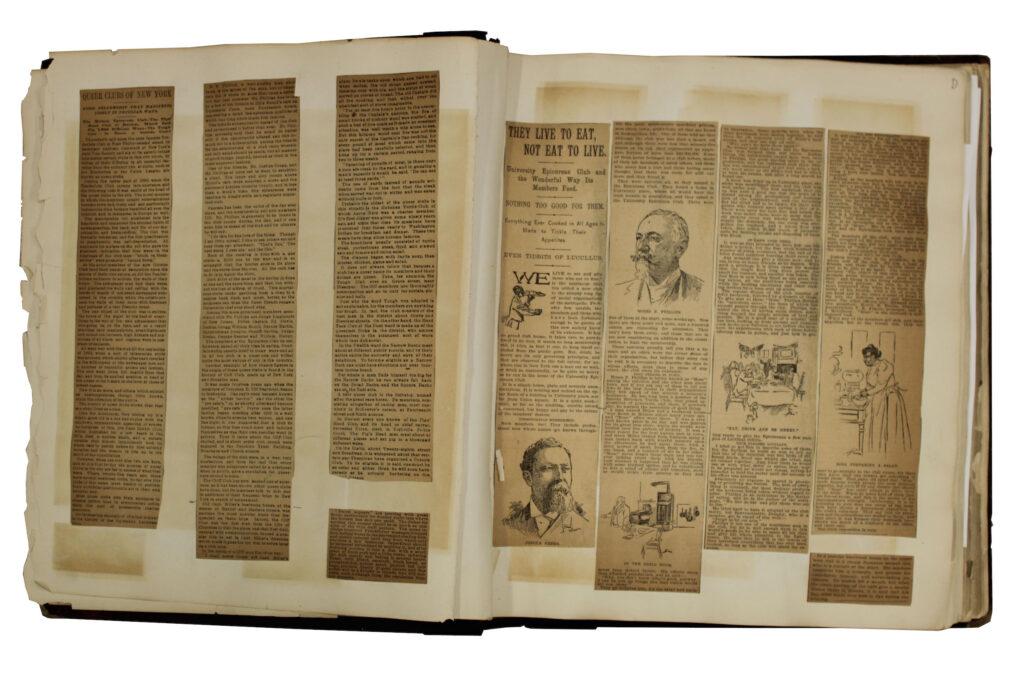

Dutch Stove Scrapbook, ca. 1880-ca. 1892. Gift of Mary Moncure Miller and family 1980.050

The Dutch Stove Scrapbook

We never imagined that the words “queer” and “beefsteak” would be used in the same article. But, apparently, this was not an unusual combination in the 19th century—when social clubs took New York City by storm. Clubs provide space for community and the gathering of like-minded individuals and, during the 19th century, frequently revolved around sharing elaborate meals, including beefsteak and epicurean clubs.

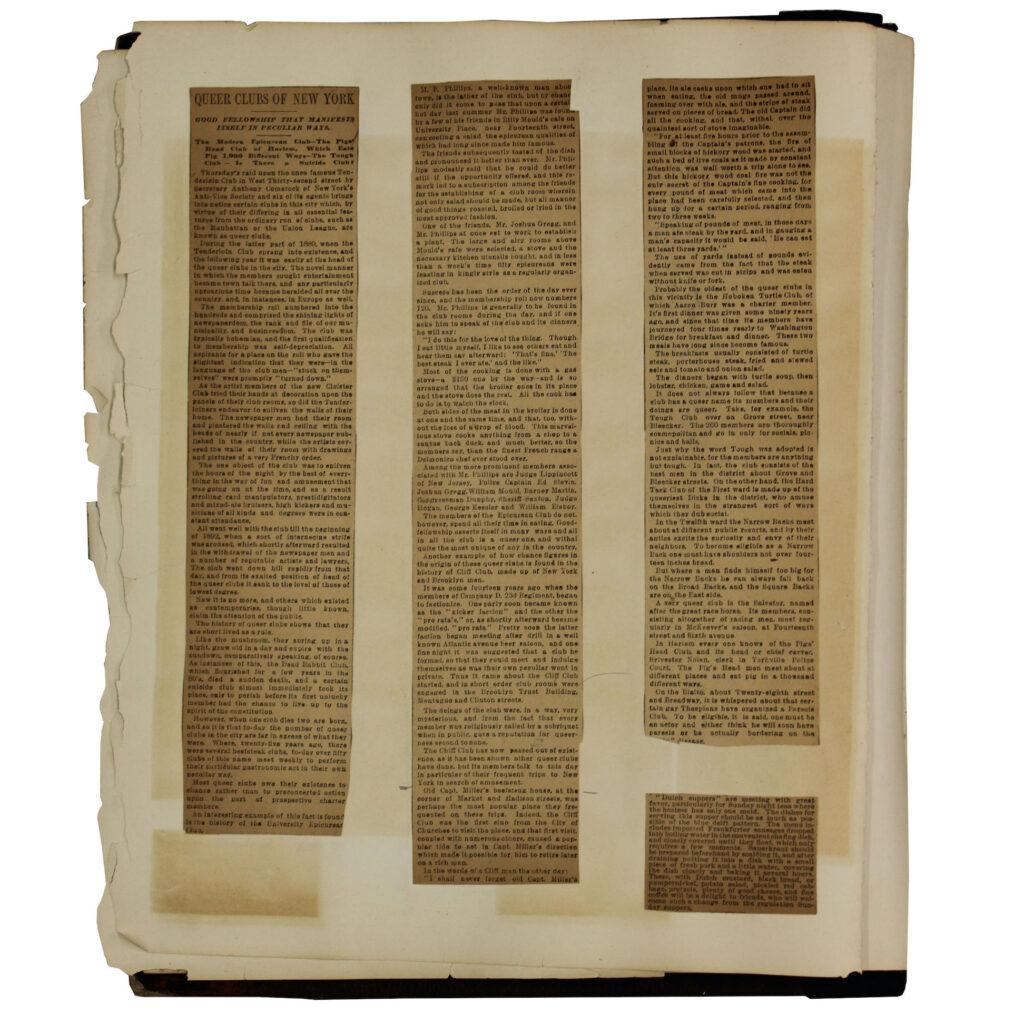

This early 1890s article is pasted into a scrapbook about Dutch stoves and William S. Miller’s famed beefsteak dinner club.

The article mentions the Old Capt. Miller’s beefsteak house (at the corner of Market and Madison Streets in Manhattan) as being frequented by the members of the queer Cliff Club.

Throughout the article, the author lists and provides commentary on a series of clubs they call queer, listing their playful club names (many clearly food-motivated) and providing witty commentary about them.

Though ensuring that “it does not always follow that because a club has a queer name its members and their doings are queer,” the author lists the following clubs: The Pig’s Head Club of Harlem (where the members bonded over eating what the title suggests), the Tenderloin Club, the Dead Rabbit Club, the Cloister Club, the University Epicurean Club, the Cliff Club, the Hoboken Turtle Club (Aaron Burr was a charter member!), the Tough Club, the Hardtack Club of the First Ward, The Salvator (“a very queer club”), and the Paresis Club.

It appears that in this context, the word “queer” was used as a subcategory to encompass clubs with peculiar members and activities. The commonality between the clubs is the nature of the club’s “mysterious doings” and members who “amuse themselves in the strangest sort of ways which they dub social.”

Out of all the clubs discussed, the Tenderloin Club stands out for its membership requisites. Members of the Tenderloin Club of West 32nd Street were described as “typically bohemian,” and required that members not be “stuck on themselves” (or, egotistical). Members were known to decorate the club’s rooms (and their homes!) eccentrically, covering them with ephemera and objects. The club existed to “enliven the hours of the night” and subsequently attracted the attendance of—in the vocabulary of the 1890s—“strolling card manipulators, prestidigitators, mixed-ale bruisers, high kickers and musicians.”

The Tenderloin Club was not initially classified as queer—it was originally formed by newspapermen who would sit across the street from the local police station of the Tenderloin District, known at time as a red-light district, to watch the nightly arrests. The club went downhill in 1892, losing the membership of reputable newspapermen and lawyers. In March 1894, the Tenderloin Club was raided by the Anti Vice Society (The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice) and shut down soon thereafter.

“Dinner tendered to Andrew T. Murtha by his friends of the Marine Insurance fraternity – at Ramos Restaurant – Greenwich Village”, June 11, 1925. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive, Maritime Reference Library

At that time, “queer” did not explicitly refer to homosexuality, but actions that were considered peculiar, mysterious, and out of the social normality. At the end of the 19th century, the terms “gay” and “queer” were not yet used to describe homosexual people. Instead, the word “fairy” was often used to indicate sexuality, with bars having “fairy” waiters who dressed in drag and performed for other men who were attracted or amused by them[2]Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940, by George Chauncey. New York, Basic Books, 1994.. Of note, the article does not mention the now confirmed drag bar, The Slide, on Bleeker Street. Places like The Slide were less like the social clubs of the time (where people paid membership dues and often gathered for long elaborate meals) and more like the nightlife clubs we know today. The omission of bars such as The Slide, which existed simultaneously with actual queer clubs, shows that in the 19th century, “queer” described people or things that did not conform with social norms.

Etymology of “queer” and reclaiming the term

For those interested in linguistics , here is the etymological digression you were waiting for. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “queer” can be traced to ca. 1500, when it was used in Scottish with the meaning “strange, peculiar, odd, eccentric.” It may have originated from the Low German queer (“oblique, off-center”) which is related to German quer “oblique, perverse, odd,” from Old High German twerh “oblique,” which can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root *terkw– “to twist.”

By 1781, the term acquired the meaning of “appearing, feeling, or behaving otherwise than is usual or normal,” which brings us closer to the modern interpretation of “queerness.” The use of “queer” to identify homosexual people was attested as an adjective by 1922, and as a noun in 1935—unfortunately, mostly as a derogatory term. As for the verb “queer,” the 1811 Lexicon Balatronicum defines it in an interesting way, that in my opinion is quite contemporary:

“TO QUEER. To puzzle or confound”

Gay liberationists in the 1960s and 1970s started to reclaim the word “queer” from its earlier hurtful usages, chanting “out of the closets, into the streets” and singing “we’re here because we’re queer.” Interestingly, The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang attests that around 1914 the term queer as “homosexual,” was “derogatory from the outside, not from within”—meaning that people were self-identifying as queer, reclaiming the term decades before the 1960s.

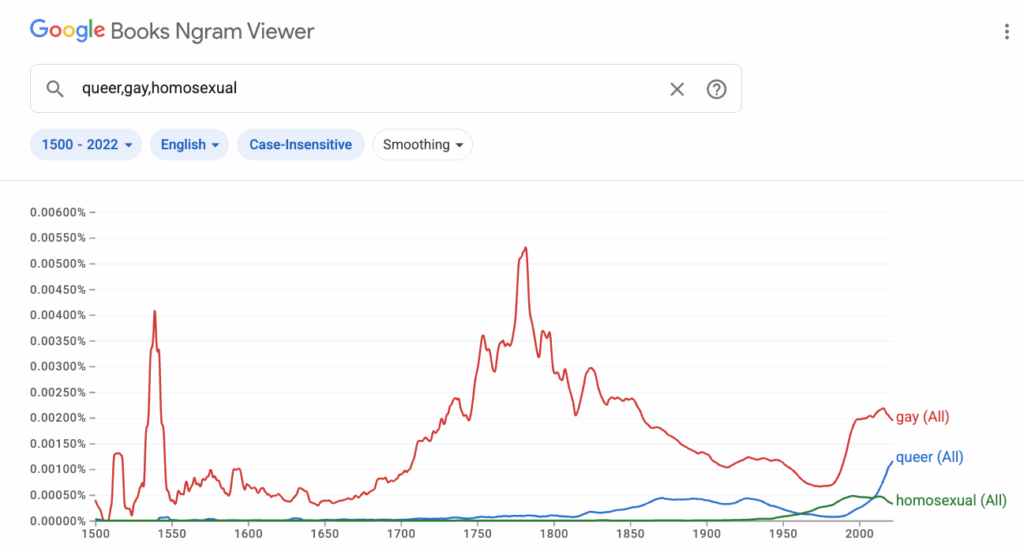

To get a visual idea of the usage of the word “queer” through time, we used Google Books NGram Viewer, an amazing digital tool that calculates the frequency of a certain word in all the published works contained in Google Books. We also decided to compare the frequency of “queer” with the words “gay” and “homosexual.”

From the chart, you can see that the usage of the word “queer” spiked towards the end of the 20th century. This makes sense, since the late 1980s were the era of the gay rights movement, spurred in part by the AIDS epidemic. The group Queer Nation, founded in the early 1990s to combat violence against gay people, was among the first to co-opt the word “queer” as a positive self-label.

Traces of Queer History in the Archival Collections

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that queer narratives are particularly hard to find in historical documents—especially considering that homosexuality was officially decriminalized in the United States in 2003 in Lawrence v. Texas, when the US Supreme Court ruled that sodomy laws were unconstitutional.

However, there are some lucky moments while inventorying or cataloging, when one of us thinks: “This looks interesting, let’s put a pin in it.” What follows are a few examples of these serendipitous discoveries.

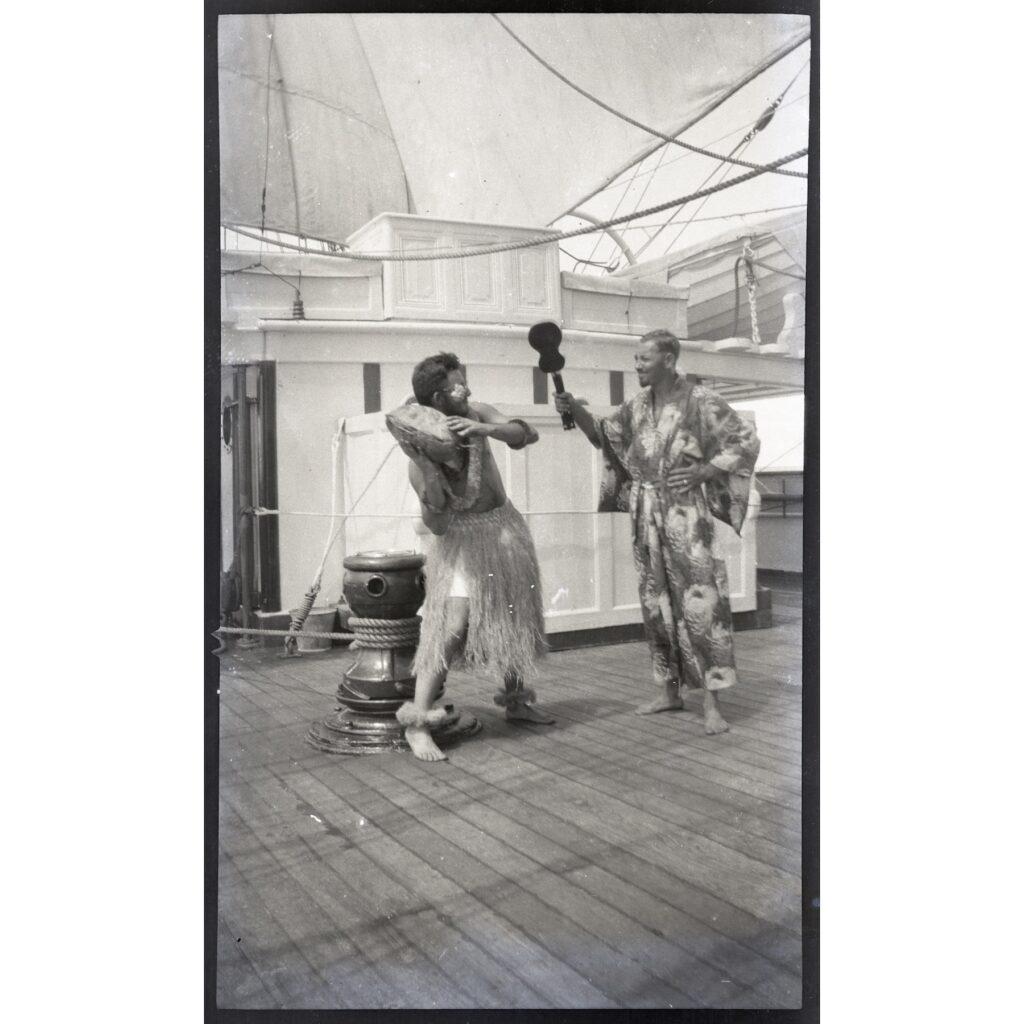

Left: [Frank Ley and Lundgrand embracing while wearing costumes on Tusitala’s deck, leaving Honolulu], 1923. Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0085

Right: [Frank Ley and a sailor wearing costumes on Tusitala’s deck], 1923-1939. Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0086

While cataloging the Captain Frank Ley Photograph Collection in 2024, the Collections Intern, River Smith, noticed a few interesting photograph negatives depicting seamen wearing clothes historically associated with women. In the left image, Frank Ley and fellow seaman Lundgrand are donning hula skirts and embracing. In the right image, Ley is wearing a kimono and another sailor is wearing a hula skirt, while they are pretending to fight with a ukulele and what appears to be a large nut or tropical fruit. In a collection that prominently features traditionally male-coded activities such as navigating, pulling lines, and killing a variety of endangered species, these images in which the seamen are allowed to break gender rules and just be playful and affectionate with each other stand out.

Another poignant image from the Captain Frank Ley Collection is the one depicting a line-crossing ceremony aboard Tusitala. The line-crossing ceremony is a centuries-old initiation ritual that takes place when a ship crosses the Equator. This tradition was first documented on French ships in the 16th century: in an era when trade routes expanded and European vessels began crossing the Equator more regularly, the line-crossing ceremony became a rite of passage in a sailor’s life.

In a line-crossing ceremony, the uninitiated members of the crew or “pollywogs” must participate in various challenges to prove their sea-worthiness to King Neptune. These challenges are administered by the “shellbacks,” the crew members that have gone through the ritual before. The shellbacks are often in costumes: a doctor, a barber, bears, and Neptune’s representative Davy Jones. An interesting ritual is the “Wog Queen Pageant,” which happens the day before the ceremony: a group of pollywogs is selected to perform in a talent show in drag, to earn the privilege to be crowned “wog queen”[3]Please note that “wog” in British English is a racial slur used to insult dark-skinned foreigners, especially from the MENA region and Asia. and sit in Neptune’s court the next day. At the end of the line-crossing ceremony, Neptune awards the participants with certificates proving their newly-conquered “shellback” status.

[Tusitala’s crew dressed in costumes for line-crossing ceremony], 1923-1939. Gift of Terry Walton 2023.007.0146

This negative features many classic elements of a line-crossing ceremony: King Neptune, holding a trident, sits in the middle next to his “wog queen.” Behind them are the shellbacks in costumes. Apart from three men in a fake uniform, there is a wizard holding binoculars, a man wearing a hat with a skull-and-bones, and another with a large hat that reads “Tusitala.” In the front row are the newly-initiated seamen, holding their certificates.

In our research of line-crossing ceremonies, we discovered that this ritual has a dark side. For some, it was a fun bonding moment; for others it was a degrading and painful experience, comparable to what we now define as hazing. In her essay Crossing the Line: Sex, Power, Justice, and the U.S. Navy at the Equator, historian Carie Little Hersh reports accounts of seamen (and women) forced to go through humiliating and degrading rituals, that sometimes escalate into physical and sexual assault. In Hersh’s opinion, the line-crossing ceremony illustrates the power dynamics of people historically discriminated against in the Navy, especially women and queer people.

While acknowledging the problematic nature of this practice, we can’t know for certain what kind of experience Frank Ley and his fellow seamen went through during their line-crossing ceremony. At the very least, we have photographic proof that there was an element of cross-dressing, of “queering” the gender norms that regulate life on land.

During the digitization and cataloging of the Egbert J.L. Jap-Ngie Collection, we came across a magazine that made us do a double take.

The Triple Punch was a magazine printed aboard T.E.L. Oriente by the members of the National Maritime Union (NMU). This issue from October 1, 1937 covers the “NMU International Revue,” a variety show held aboard the Oriente to entertain the crew.

Among musical and comedy performances, it’s Act 1 that stands out:

“Act 1. The Rank and File Ballet, a well trained aggregation of chorus girls including Albert Herrick, Bert Lloyd, Charles Davis, Billy Muir and Frank Moran—direct from the Club Lineen—who, in their burlesque of the “Spring Dance,” had the audience splitting with laughter.”

“The Triple-Punch: Understanding and Progress in the National Maritime Union”, October 1, 1937, page 1. Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie 1995.008.0010

While the dance performance was probably meant to be ridiculous, and the cross-dressing component mostly played for laughs, it is indeed interesting that these seamen—clearly identifiable by their names—were comfortable being mentioned and photographed while dressed like women. The whole show sounds like a mix of high-brow and (mostly) low-brow acts, as we can tell from this description of Act 2:

“A clever skit in which Herb Harris sang, H. Benkus acted the ‘drunk,’ Faverman took the part of a lady, and Oake stole the show by his imitation of a pig.”

Even here, a seaman is playing a woman’s part; a fact that is not presented like a big deal at all.

Detail from “The Triple-Punch: Understanding and Progress in the National Maritime Union”, October 1, 1937, page 1. Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie 1995.008.0010

Simple Questions, Complex Answers

After all these examples, the question remains: were any of these seamen queer by today’s standards? Unsurprisingly, the answer is complex. The National Museum of the Royal Navy offers an interesting perspective on the topic in a blog post about line-crossing ceremonies:

“We should consider the ethical implications of giving an identity to someone who we cannot talk to and ensure that we are not suggesting that such cross-dressing automatically created an LGBTQ+ friendly environment during a time when such expressions were illegal.”

Projects like the 2019 documentary The Lavender Scare illustrate how dangerous it was to be queer in the US Army or government in the mid 20th century. In a clip from the documentary, Navy Captain Joan Cassidy recalls the scare tactics that the Army used to expose queer people—she ultimately decided to leave active duty for fear of being outed as a lesbian.

Considering how homophobia permeated American society until recent years, it’s not surprising that queer stories are so hard to find in archival collections. Our hope is that, as times change and queer people feel free to tell their story, all these lost pieces will come to the surface.

Additional Readings and Resources

“A Dictionary of Buckish Slang, University Wit and Pickpocket Eloquence” by C. Chappel, United Kingdom, 1811.

“Crossing the Line: Sex, Power, Justice, and the U.S. Navy at the Equator.” by Carie Little Hersh. Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy 9, 2002, pp. 277-324.

“Lavender Scare: U.S. Fired 5,000 Gays in 1953 ‘Witch Hunt’”, by ABC News, March 5, 2012.

“Behind the Strange and Controversial Ritual When You Cross the Equator At Sea”, by Cale Weissman, Atlas Obscura, October 23, 2015.

“How the word ‘queer’ was adopted by the LGBTQ community”, by Merrill Perlman, Columbia Journalism Review, January 22, 2019.

“Queer History Article” by Christina B. Hanhardt, in The American Historian, Organization of American Historians, May 2019.

“Shellback and Other Navy Ceremonial Certificates. A Select Bibliography”. Naval History and Heritage Command, 2019.

“‘Queer’ history: A history of Queer“, by Mollie Clarke, The National Archives, February 9, 2021.

“What are ‘Crossing the Line’ ceremonies?”, National Museum of the Royal Navy, June 13, 2023.

“The history of the word ‘queer’“, by Associate Professor Timothy W. Jones, La Trobe University, January 19, 2023.

References

| ↑1 | See the definition of “queer” as it’s used today, from The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center:

“An adjective used by some people whose sexual orientation is not exclusively heterosexual or straight. This umbrella term includes people who have nonbinary, gender-fluid, or gender nonconforming identities. Once considered a pejorative term, queer has been reclaimed by some LGBTQIA+ people to describe themselves; however, it is not a universally accepted term even within the LGBTQIA+ community.” What Is LGBTQIA+?, The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center (The Center), https://gaycenter.org/community/lgbtq/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940, by George Chauncey. New York, Basic Books, 1994. |

| ↑3 | Please note that “wog” in British English is a racial slur used to insult dark-skinned foreigners, especially from the MENA region and Asia. |