Newspaper Clippings Now on the Collections Online Portal

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

June 29, 2023

Despite the proliferation of online newspapers and digital news sources, there is something about printer’s ink on a piece of paper that makes it worthy of keeping. Individuals and institutions have collected newspapers as souvenirs of historical and personal importance for centuries; and today, newspaper front pages are often saved as a memento of events of historical and educational significance, from 9/11 to the Women’s March and the many firsts in politics.

When looking at the South Street Seaport Museum’s collections and archives, newspaper clippings complement and permeate the history of our artifacts, ships, historic buildings and neighborhood. Front pages, full-pages, interior spreads, and small clippings inform, document, and enrich the Museum’s collections with eyewitness accounts and illustrations of New York and American social, architectural, and commercial environments.

Today, I’m pleased to share some good news. The first wall-to-wall inventory of the Seaport Museum’s newspapers’ clippings and illustrations that are formally accessioned as part of the Museum’s art collection has concluded. Of over 1,400 items, a small but mighty selection is now available online for everyone to browse and search on our free Collections Online Portal.

Having just finished the first phase of this inventory and digitization project, I have found myself amazed at the diversity of images preserved in these pages. I’m struck by how visually rich they are from compelling illustrations and fascinating political cartoons, to prominent headlines and recollections of important moments of the past.

So, let me briefly guide you through how we finally reached this moment, starting with a brief history of newspapers in America, the newspapers the Museum collects, and how here at the Seaport—and everyone in their own homes—can care for and access them for future generations.

Brief History of Newspapers

Did you know that the ancient Romans are commonly credited to have first created newspapers? The Acta Diurna, or daily doings, is considered the first handwritten paper, and although no copies have been preserved, scholars believe that it has included chronicles of events, assemblies, births, deaths, and daily gossip. A few centuries later, again in Italy, but this time in Venice, avisi, or gazettes, are recognized as another ancestor of the modern newspaper. These Renaissance Venetians papers were also handwritten, but differently from the ancient Roman ones, focused mostly on politics and military conflict updates.

The absence of printing-press technology greatly limited the circulation for both Italian papers, and it was with the birth of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1390–1468?) that publishing and journalism changed drastically.

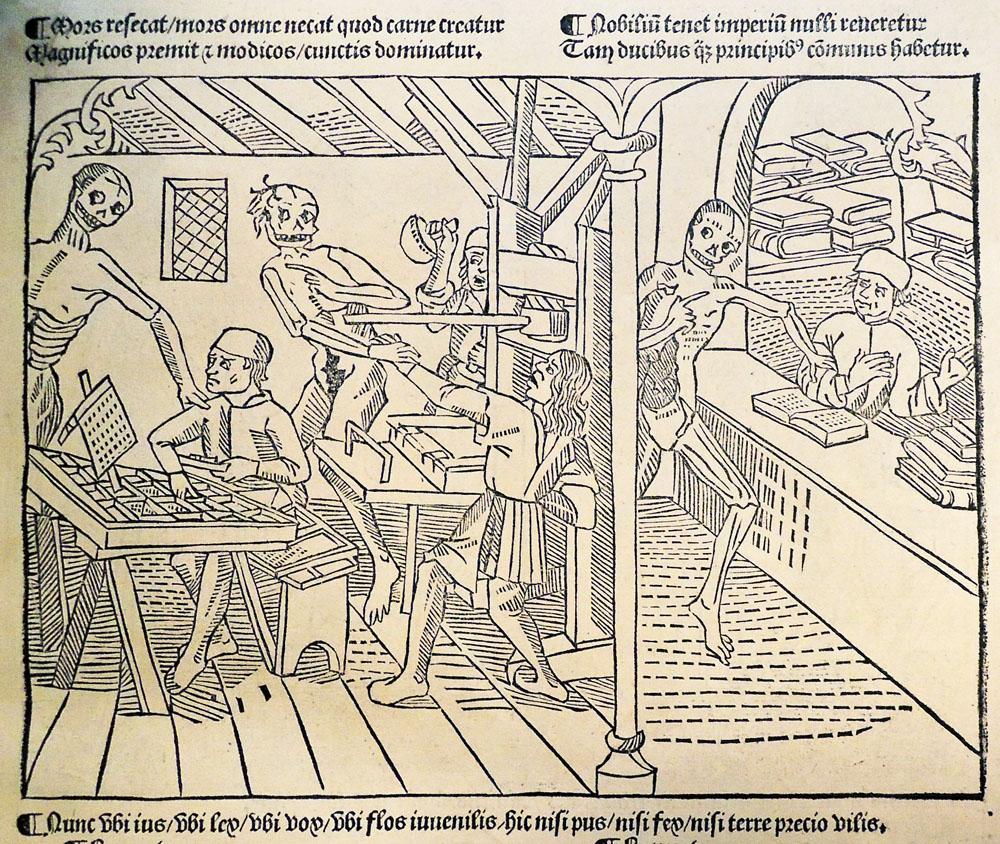

Gutenberg’s 1440 movable-type press drove down the price of printed materials and, for the first time, made them accessible to a mass market. The new printing press, seen here in the first illustration of a printing office and a working printing press ever known, transformed the scope and reach of books and newspapers, ushering in an “information revolution” that paved the way for modern-day journalism.

Two hundred years after the moveable-type press invention, and after many concerns over persecution, newspapers spread throughout Central Europe. By 1641, a newspaper was printed in almost every country in Europe from France and Germany, to Italy and Spain.

“La grāt danse macabre des hōmes, des fēmes hystoriee, augmentee de beaulx dis en latin. Le debat du corps et de lame. La cōplainte de lame dampnee. Exortation de bien viure, bien mourir. La vie du mauuais antecrist. Les quinze signes. Le iugement.” [With woodcuts.] G.L. ([Mathias Huss:] Lyon, le .xviii. iour de feurier, 1499). Scheide Library, Princeton University.

Newspapers did not come to the American colonies until September 25, 1690, when Benjamin Harris (1647–1716) printed the first English-American news sheet, the Boston’s Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick. In the decades following, Americans became heavy readers of broadsheets and tabloids as they were looking for news from their countries of origin, for news about the American Revolution, and for the political debates of the newly established United States. Most colonial newspapers were weeklies, had four pages, and printed most of their advertisements in the back. Printers kept many stories brief, and divided news by type, including a section for comment on political events, which were the precursor of today’s editorial.

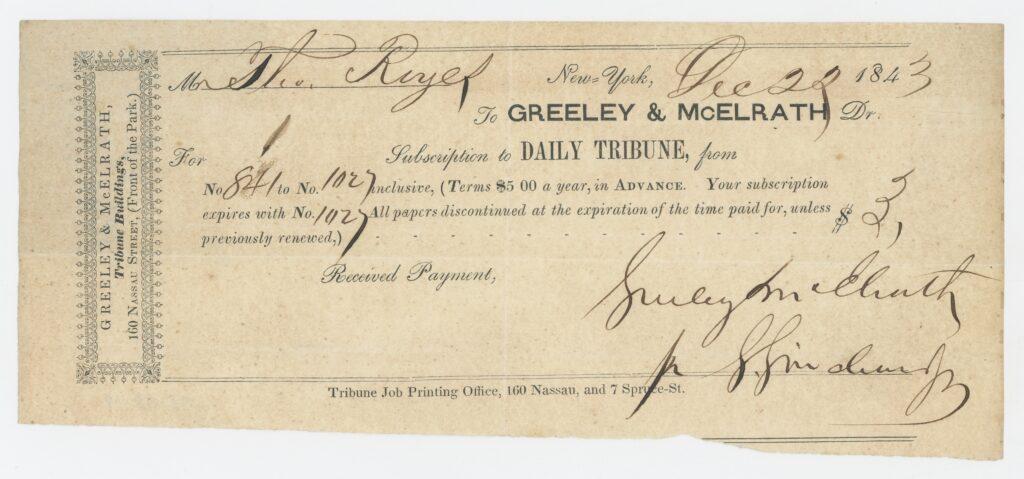

Tribune Job Printing Office, printer. “Subscription Receipt to the Daily Tribune” December 22, 1843. South Street Seaport Museum 1985.098.0019

In the early 19th century, daily papers became more common and gave merchants up-to-date vital trading information, but most of them were priced well above what working-class citizens could afford. As such, newspaper readership was limited to the elite, but it took the industry only a few decades to flourish with cheaper versions. Subscriptions became available, like the one above for the Daily Tribune that was $5 for a year of papers!

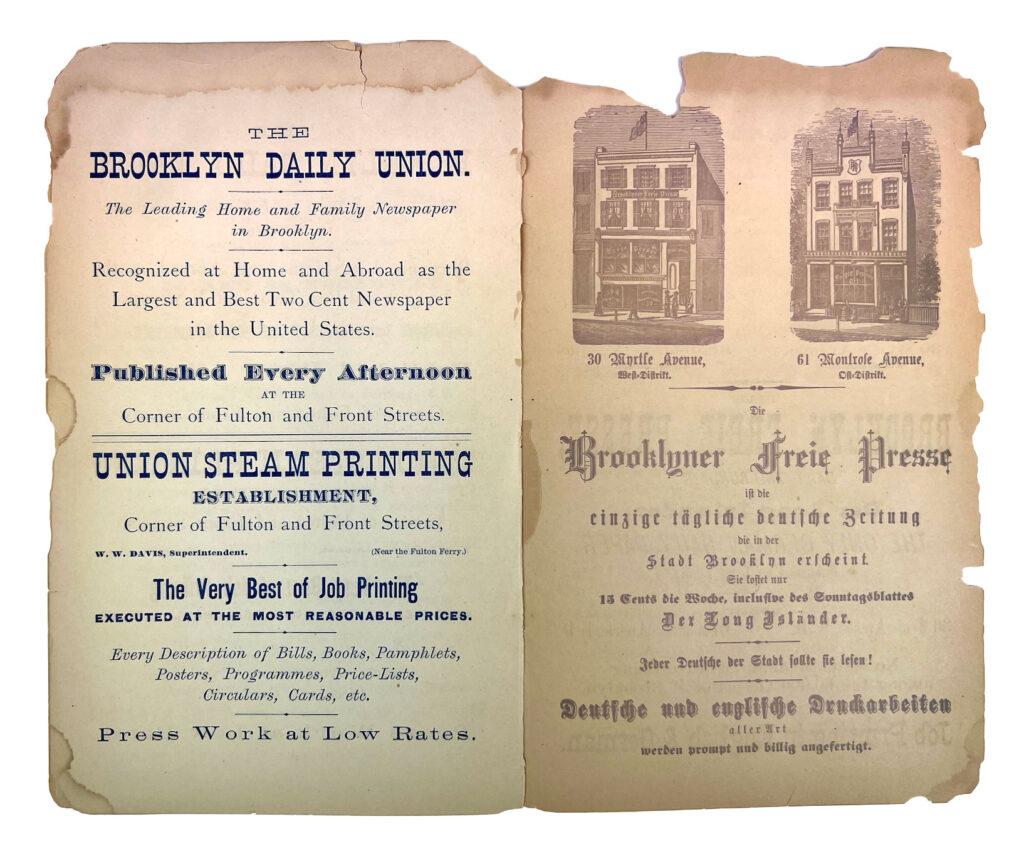

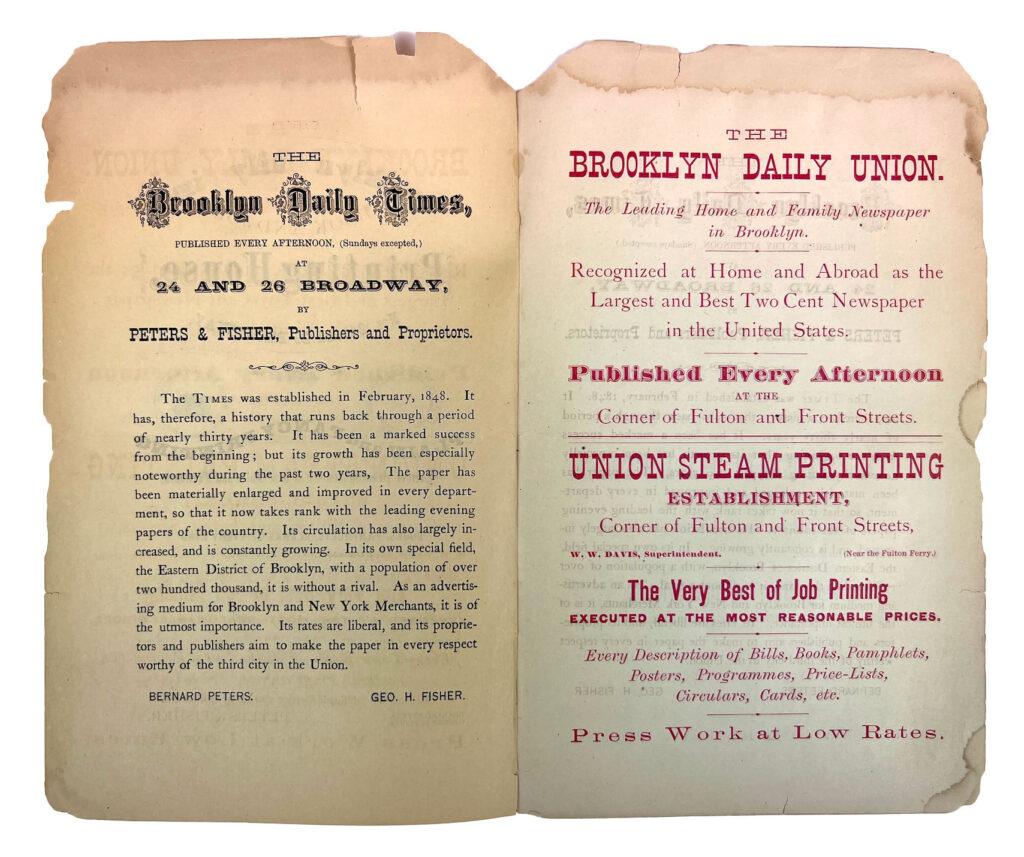

Peters & Fisher, printer. [Advertisement for the Brooklyn Daily Times, The Brooklyn Freie Press, and the Brooklyn Daily Union] late 19th century. South Street Seaport Museum 1985.112.0027

By the 1830s the United States had some 900 newspapers, about twice as many as Great Britain—and had more newspaper readers, too. The 1840 United States census counted 1,631 newspapers, and by 1850 the number had doubled to 2,526, with a total annual circulation of half a billion copies for a population of under 23.2 million people.

Newspaper Clippings at the Seaport Museum, Part I

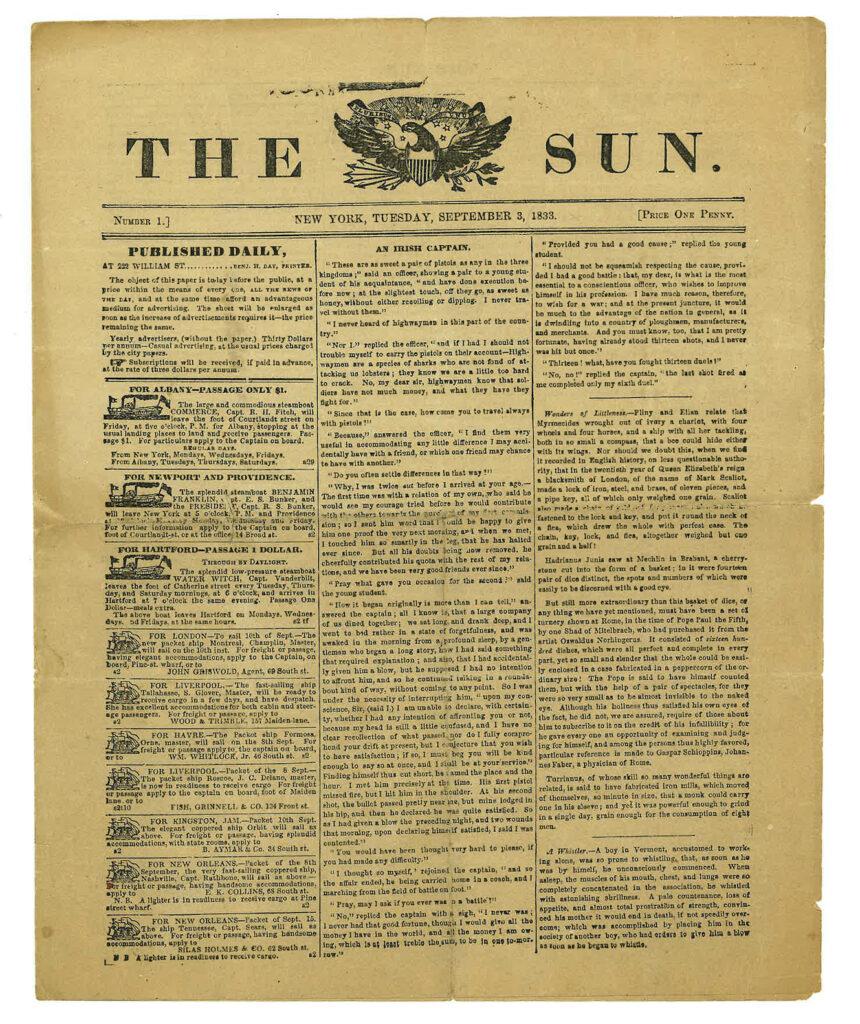

One of the Museum’s most precious newspaper clippings is an edition of the Sun, dated September 3, 1833, the year it was established. The New York Sun is the first so-called “penny paper” because it targeted the middle and lower class readers, who could afford only a penny a day for a newspaper, rather than the six cents charged by most dailies.

This four-page morning newspaper was printed and published by Benjamin H. Day (1810–1889). He emphasized local news and events, police court reports, and advertisements.

Our copy here shows on the cover many notices for scheduled trips of steamboats and packet ships and a humorous story, while the interior pages have ads for insurance companies, educational schools and warehouses, news of murders and trials, marriages and death notices, rewards for thefts, and sales by auction.

The Sun was very successful and inspired other penny papers, including the New York Herald and the New York Tribune. By 1834, the Sun had the largest circulation in the United States, and by 1842 New York City recorded having nine one-penny and two-penny dailies, and seven traditional six-penny dailies.

Benjamin H. Day, printer. “The Sun, No. 1” September 3, 1833. Gift of Elizabeth R. Holmes 1981.038

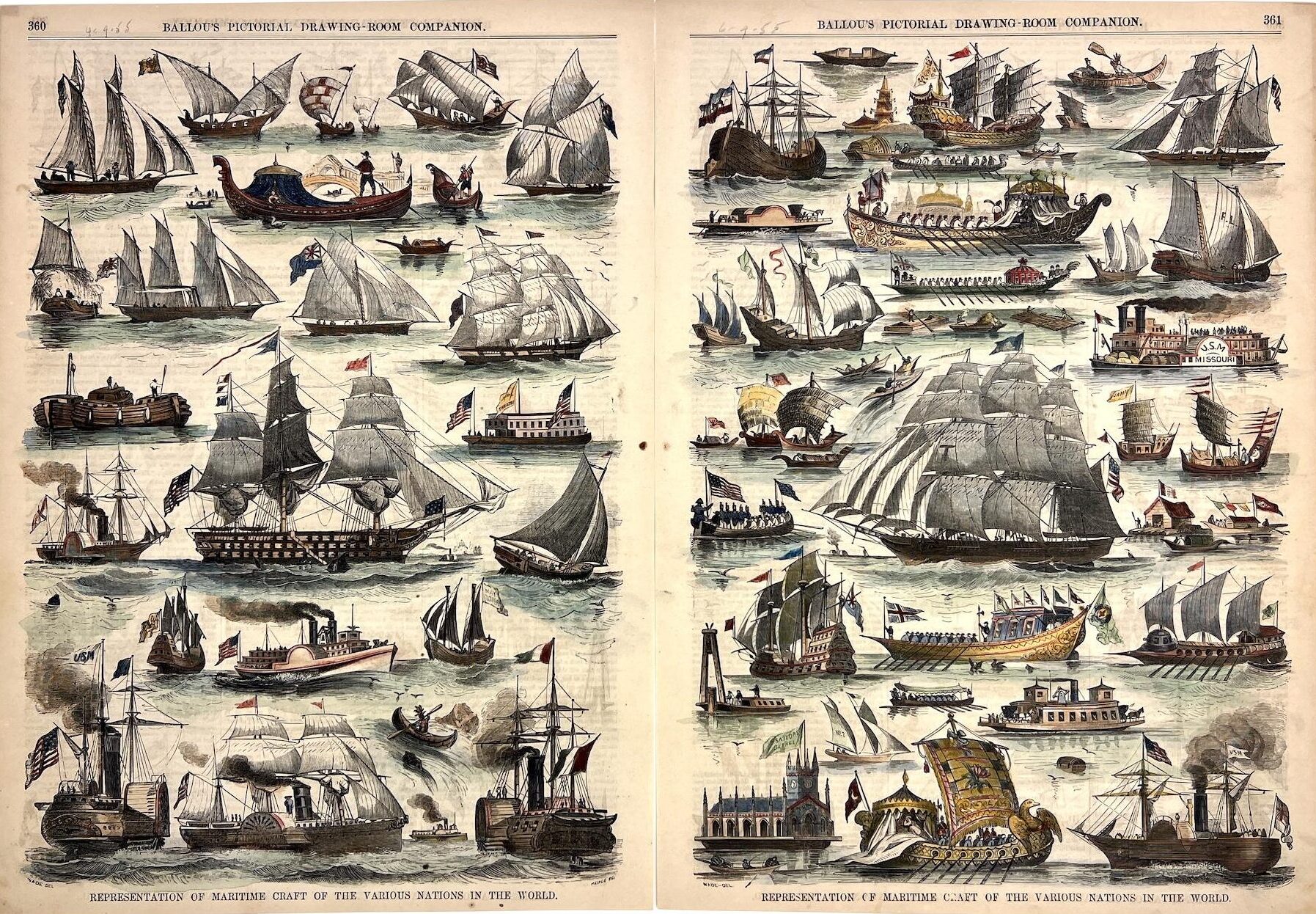

Until the 1850s, newspapers featured few images. There might be a small woodcut to signify an incoming ship, but nothing directly related to news events. The core of the Seaport Museum’s newspaper collection features pages from illustrated newspapers from the 1860s to the 1890s.

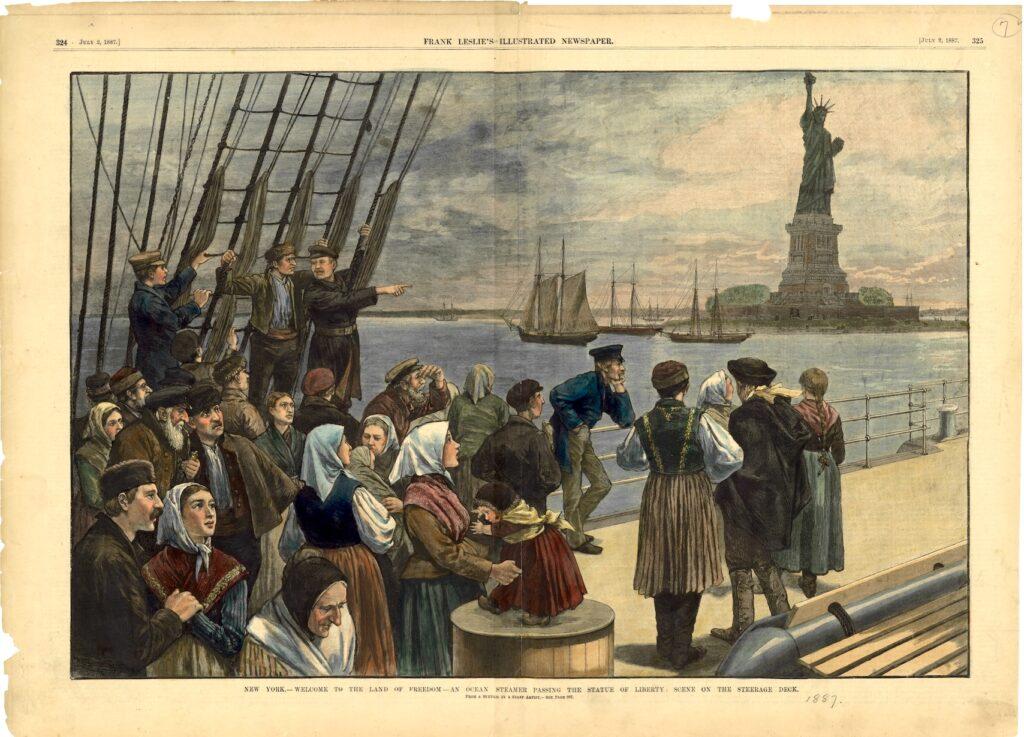

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, established in 1855, was the first successful pictorial newspaper in the United States. It was published by Frank Leslie (born Henry Carter, 1821–1880), an English immigrant who had worked for six years in the engraving department at the London Illustrated News before coming to North America.

Though Leslie’s would become a great success, its first few years were plagued by instability. Activism, sensationalism, and tell-alls were the solution for a stable readership.

This illustration is one of my favorites, as it is an inspiring and impactful two-page spread published less than a year after the Statue of Liberty was dedicated. The accompanying article describes the immigrants’ experience as follows:

“…the first glimpse of the shores of this Land of Promise must indeed be inspiring and joyful, and as they sail up our beautiful Bay and for the first time see the majestic statue of Liberty, standing, so to speak, at the very gateway of the Republic, we cannot wonder at their exultation should, as it often does, find enthusiastic expression.”

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, publisher. “New York – Welcome to the Land of Freedom – An Ocean Steamer Passing the Statue of Liberty: Scene on the Steerage Deck” July 2, 1887. Gift of Fritz Gold 1994.017.0005

The association between the State of Liberty and immigrants was largely based on its context; New York Harbor was the entry point for millions of immigrants to the United States in the decades around the turn of the 20th century. The Statue of Liberty was a powerful sign to new migrants that they had arrived after their transatlantic voyage.

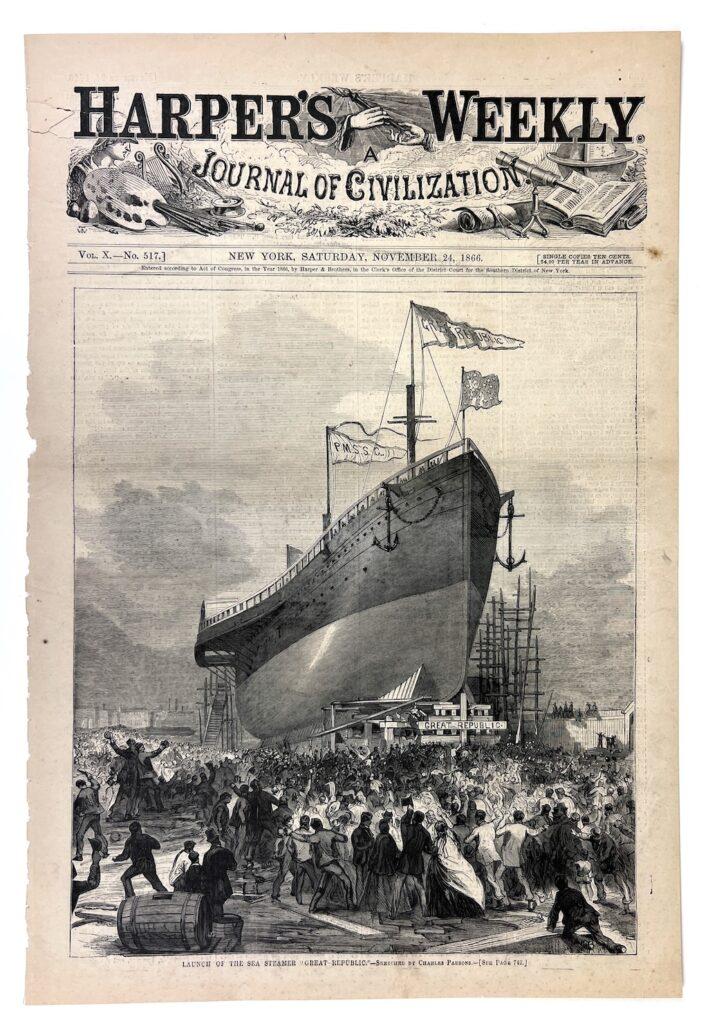

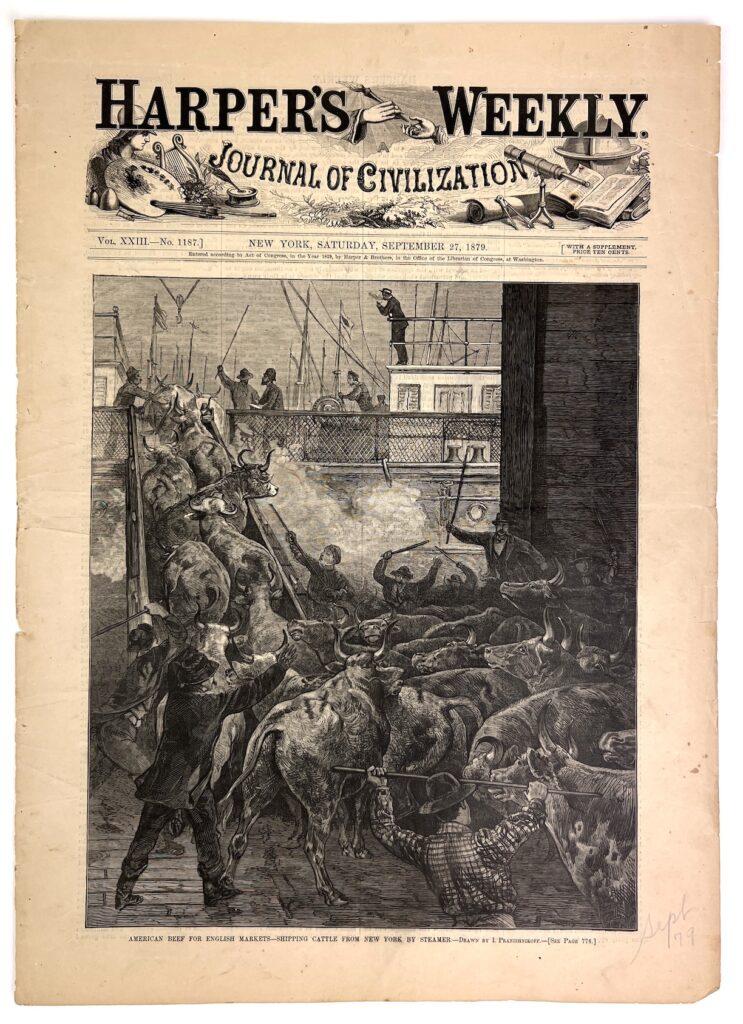

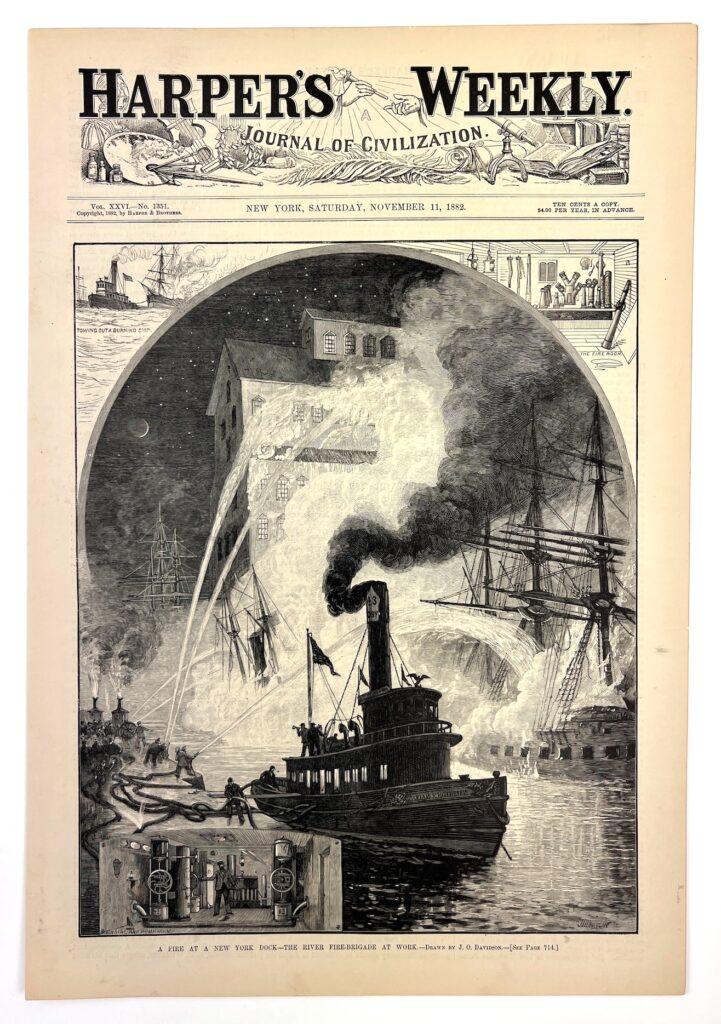

Unlike Leslie’s, which focused heavily on news events and tabloid journalism, Harper’s followed the model of its magazine progenitors, carrying less news and more literary content, creating for itself a more serious and respectable reputation.

Left: “Launch of the Sea Steamer “Great Republic”” November 24, 1866. Gift of Mavis P. Kelsey 1998.007.0700

Center: “American Beef For English Markets–Shipping Cattle From New York By Steamer” September 27, 1879. Gift of Mavis P. Kelsey 1998.007.0033

Right: “A Fire at a New York Dock – The River Fire-Brigade at Work” November 11, 1882. Gift of Mavis P. Kelsey 1998.007.0079

Harper’s Weekly became the most widely read weekly magazine of the era, featuring foreign and domestic news, essays, illustrations, and humorous cartoons. The illustrated political magazine was printed by the New York City publishing house Harper & Brothers from 1857 to 1916, and only three years after its circulation began, in 1860, it had 200,000 subscribers.

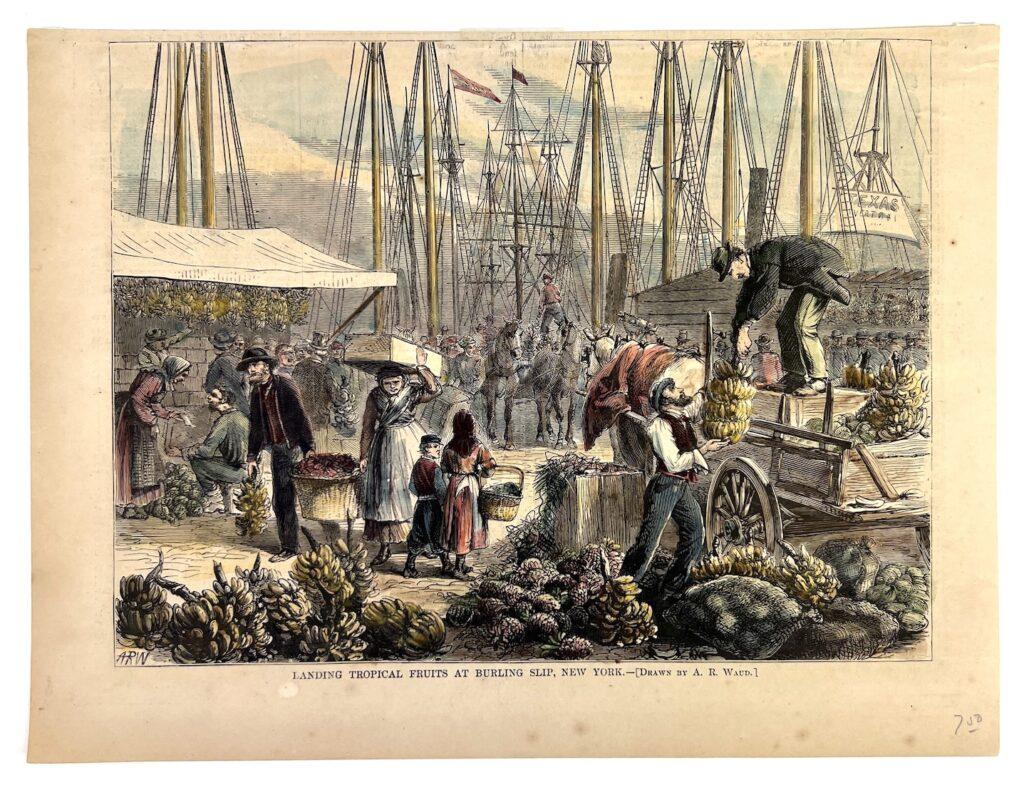

The engraving below, from a lower page of a Harper’s Weekly published in June of 1870, shows a bustling scene along the East River with New Yorkers unloading and selling tropical fruits. Bananas are the most visibly recognized fruit in the illustration, and in 1870 were a delicacy unavailable to Americans living inland.

Harper’s Weekly, publisher. “Landing Tropical Fruits at Burling Slip, New York” June 18, 1870. South Street Seaport Museum 1988.096

It appears that Americans did not easily embrace foreign fruits. I recently learned that in the 1840s, President Martin van Buren (1872–1862) famously complained that pineapples were too decadent and aristocratic, while native apples, in contrast, were argued to be “the” American fruit by social reformer Henry Ward Beecher (1813–1887).

This illustration contextualizes the new exotic fruit in this specific historic moment in time, knowing that it was only a few years later that several entrepreneurs capitalized on advancements in refrigeration and transportation technologies to make the fruit more accessible to American consumers.

Reading and looking at some of our newspaper clipping illustrations always makes me think about what viewers might have learned about the topic, in this case this fruit, after seeing it in a newspaper.

Newspaper Clippings at the Seaport Museum, Part II

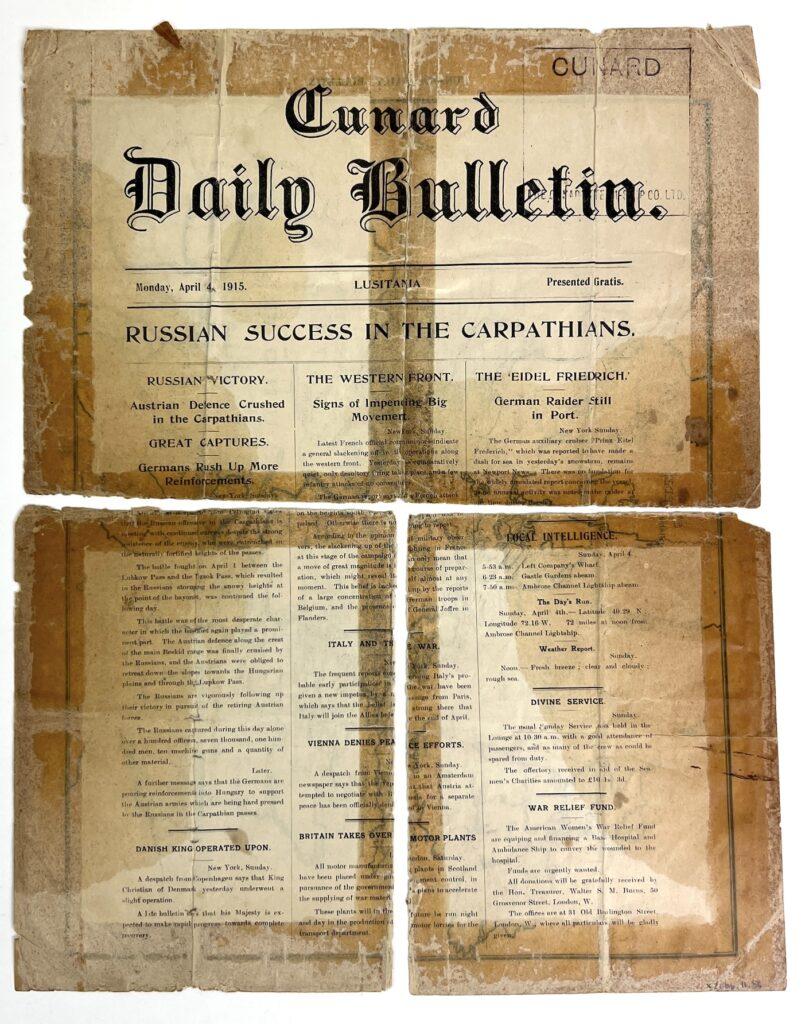

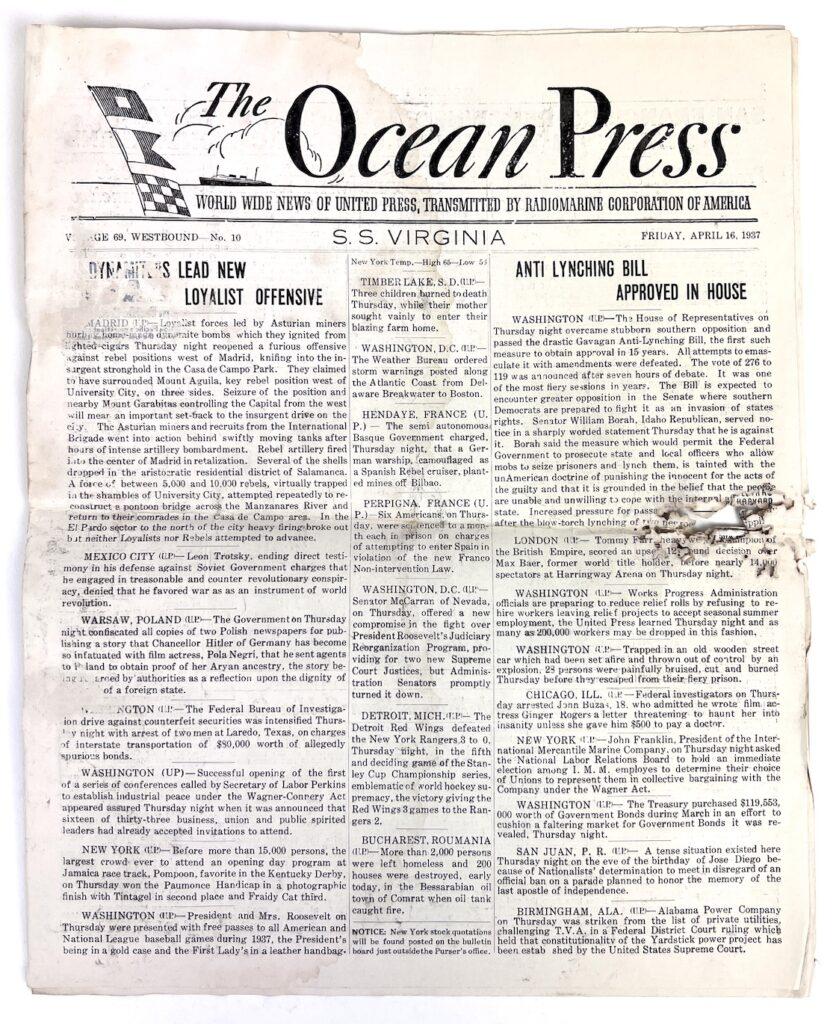

The amount of visually striking illustrations in our newspaper clipping collection should not obscure other types of newspapers in the Museum’s collection, equally interesting and in need of preservation and care.

Ocean liner gazettes, clippings glued into scrapbooks and ship logs, and clippings considered maritime reference materials for the former Museum’s Library are not currently available online, but are our next steps in inventorying and cataloging the Museum’s special collections, for the most part underway.

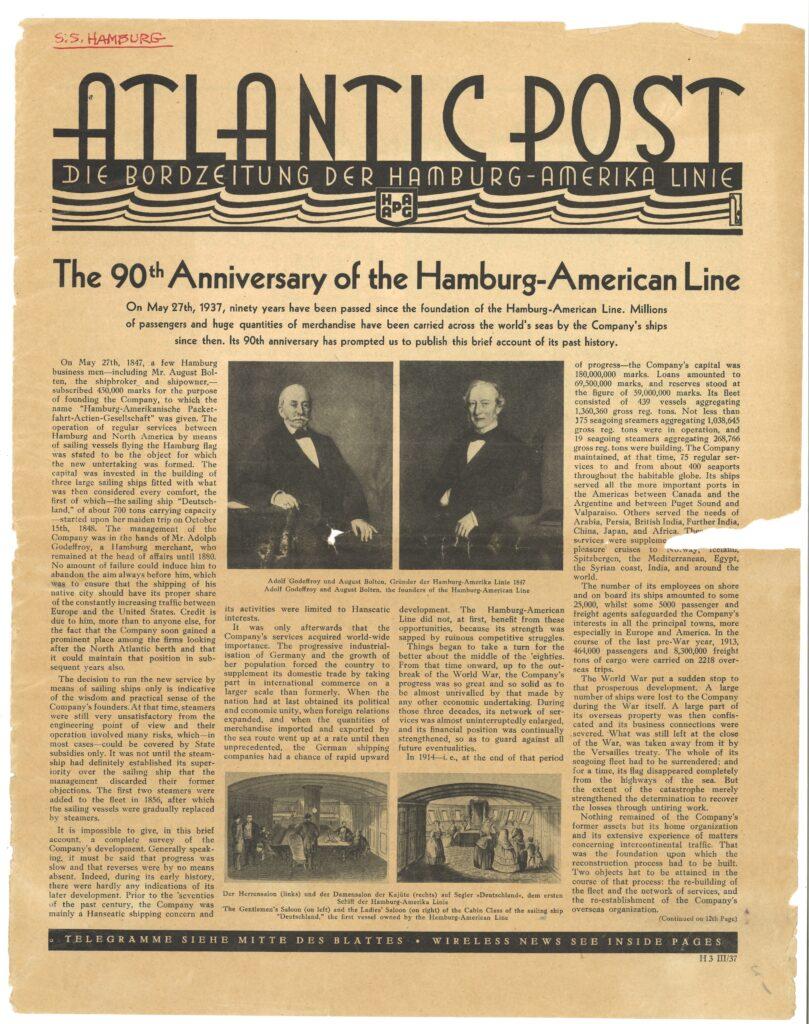

Left: “Cunard Daily Bulletin” April 4, 1915. From the Estate of Peter Radmore 2006.011.0056

Center: “SS Virginia, The Ocean Press” April 16, 1937. South Street Seaport Museum 2002.027.0008

Right: “Hamburg American Line Atlantic Post” May 17, 1937. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.4745

Our travel-related newspapers, newsletters, and magazines encompass several steamship lines, including but not limited to the Inman Line, Cunard Line, French Line, Hamburg American Line, and Norddeutscher Lloyd.

The first ocean liner company to inaugurate newspapers printed on board transatlantic liners was the Cunard Steamship Company. On February 7, 1903 on board SS Etruria, a four pages pamphlet called the Cunard Bulletin, was printed. This service proved so popular that similar papers were established on other Cunard’s ships, and it was enlarged. In some cases, it became a 32-pages gazette containing the latest news in the world (thanks to the invention of the wireless telegraph by Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937)), poetry, contemporary illustrations, puzzles, and an active line of advertising. The Cunard Daily Bulletin, like many other liner companies’ papers, became an important souvenir of the trip, kept and collected by passengers and crew members.

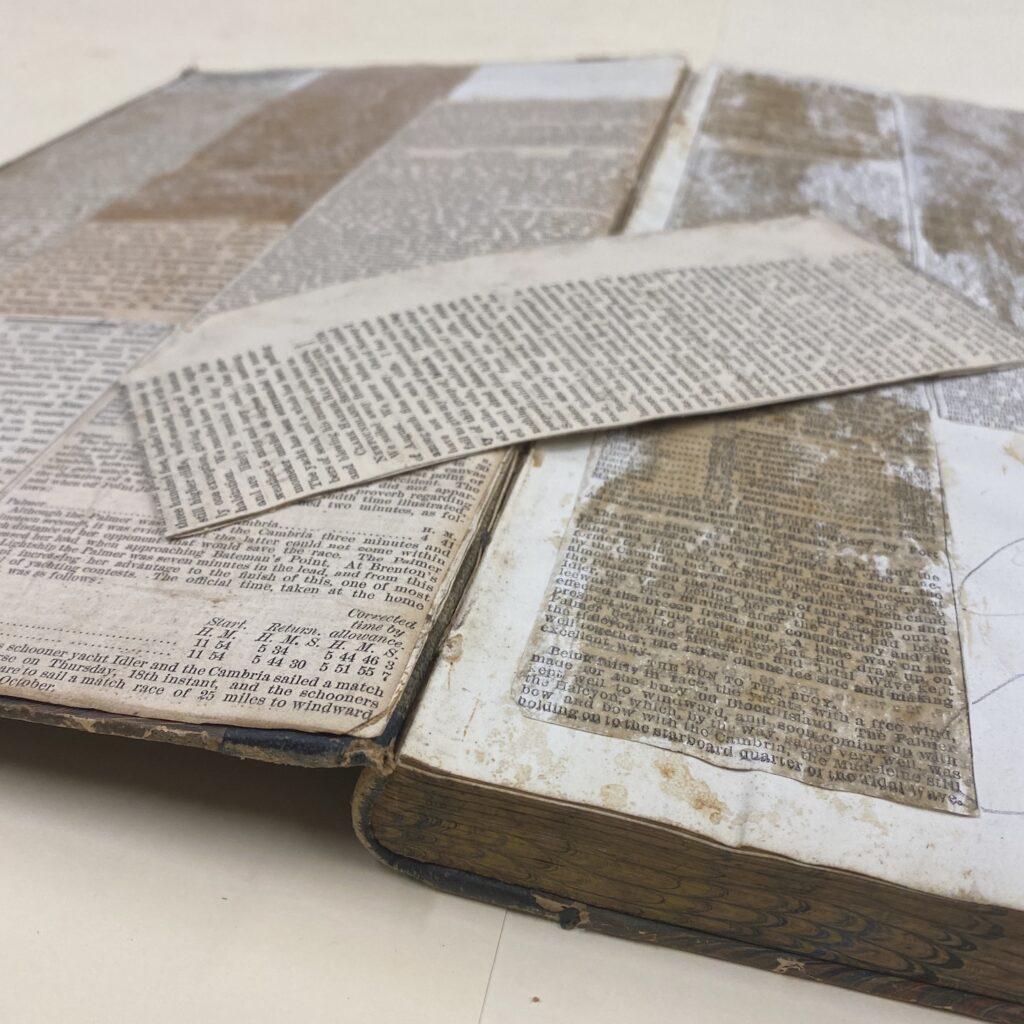

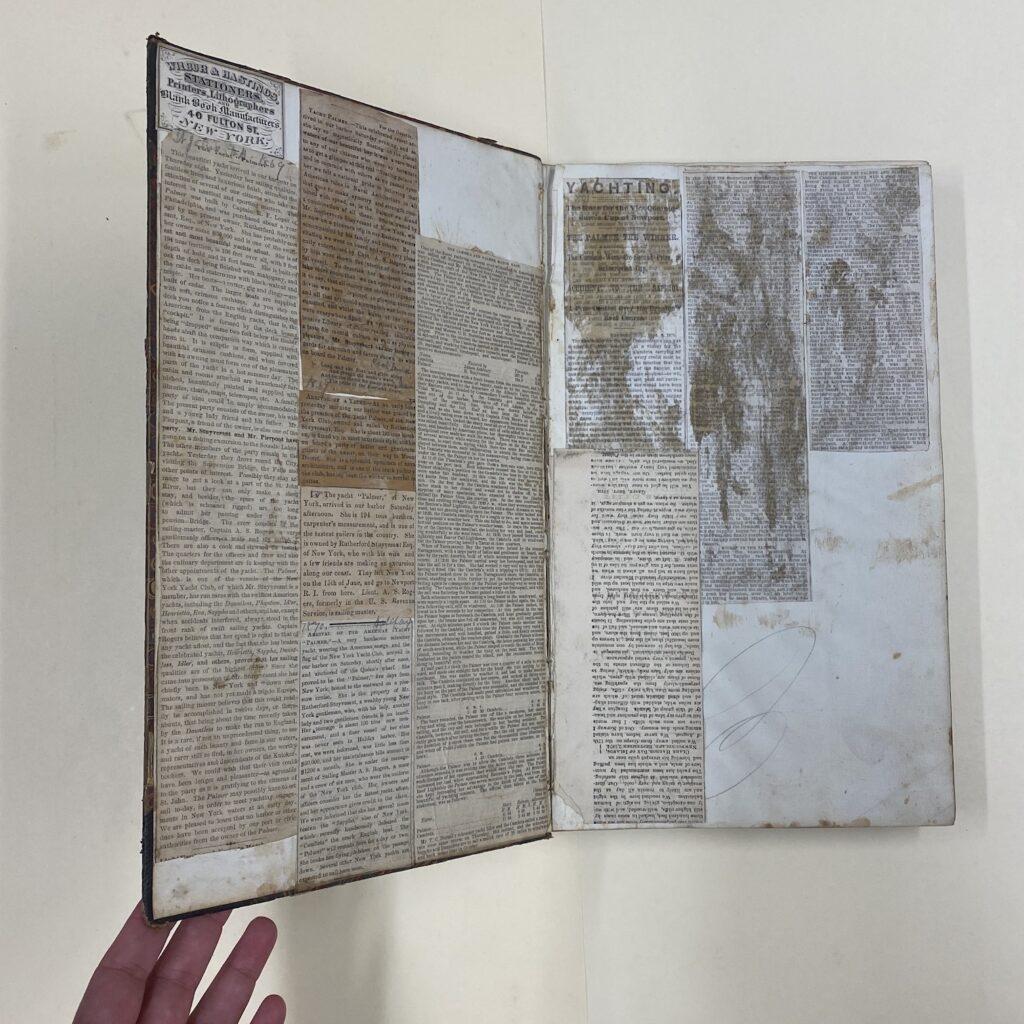

Clippings in the Seaport Museum’s collections and archives are also heavily present in scrapbooks, but the eclectic nature of scrapbooks represent a preservation challenge due to their mixed media contents and the composition of the books themselves.

The first step in this group of items is to determine their condition and any handling limitations. Many scrapbooks used materials that we know today are not easily preserved over long periods of time. Nonetheless, we must accept—and treasure—them for what they are: unique gatherings of material that are best preserved as an intentional, singular, unit.

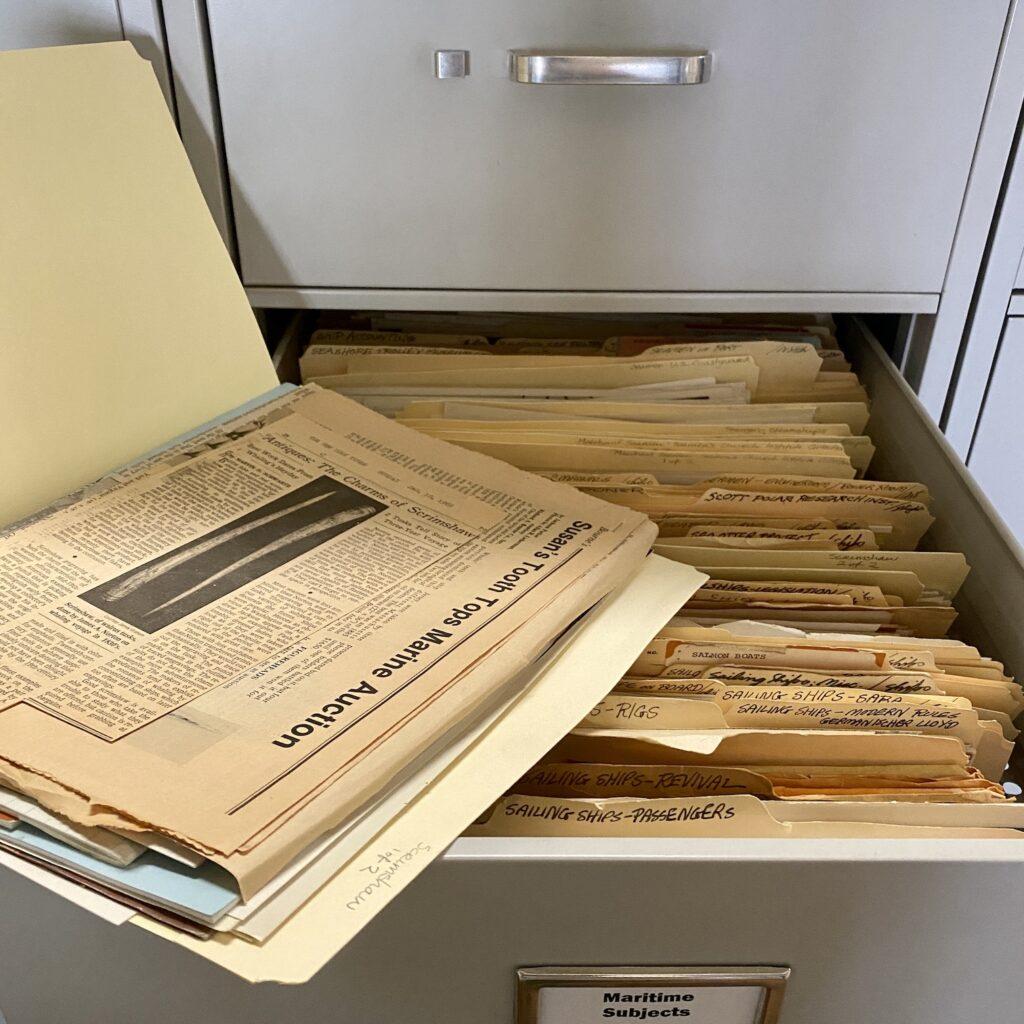

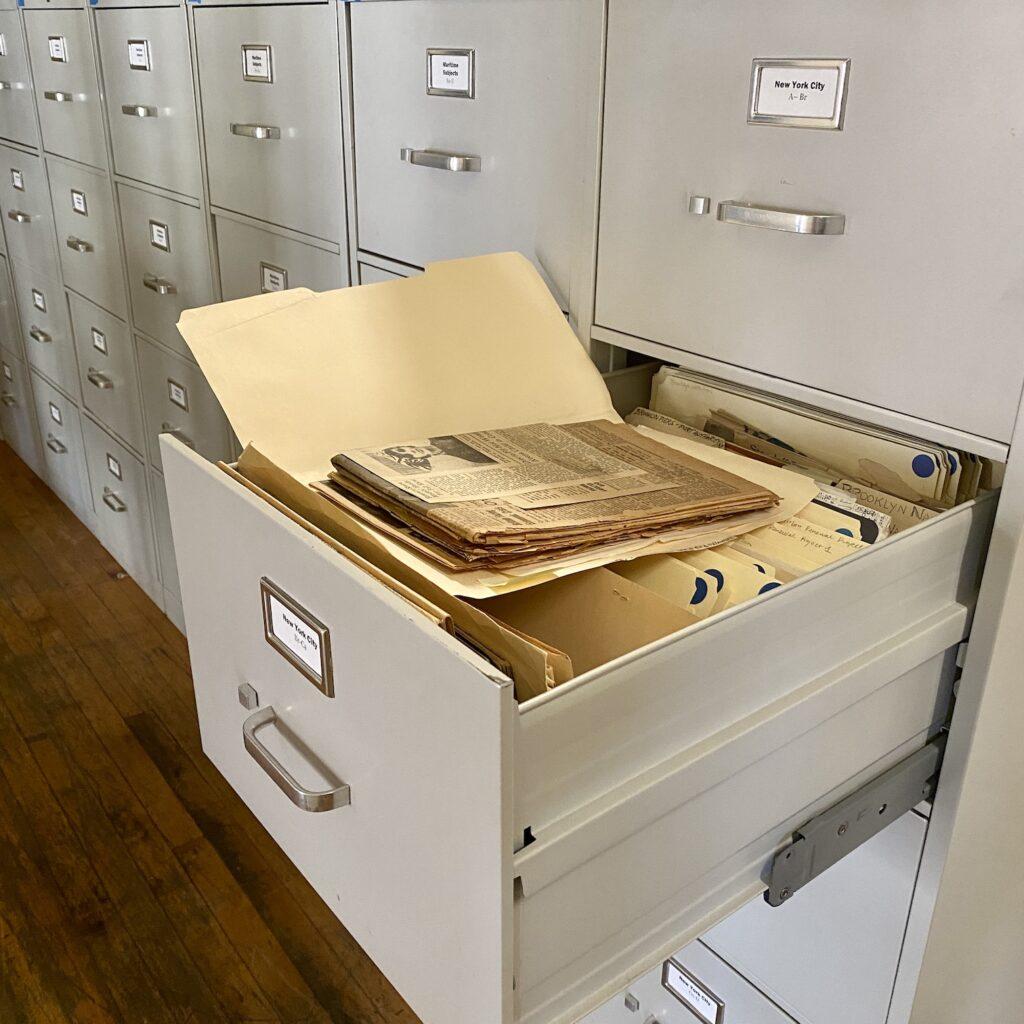

Lastly, we also own many more clippings “sprinkled” throughout our maritime reference materials. The subject files we inherited are what we colloquially call “the life before Google”. They are reference files, containing materials related to different subjects.

Each subject has one or more folders, organized by topics, including newspaper clippings as well as brochures, photocopies, handwritten notes, research papers, and occasionally photographs. Though the majority of these items are from the 1960s and onwards, we occasionally discover 19th century clippings and photographs in the mix!

Similarly to scrapbooks, these files are a preservation challenge and their condition is a key element to consider if and how they can be handled and digitized, and how often items can be pulled for examination and research.

Challenges and rewards of a successful inventory project

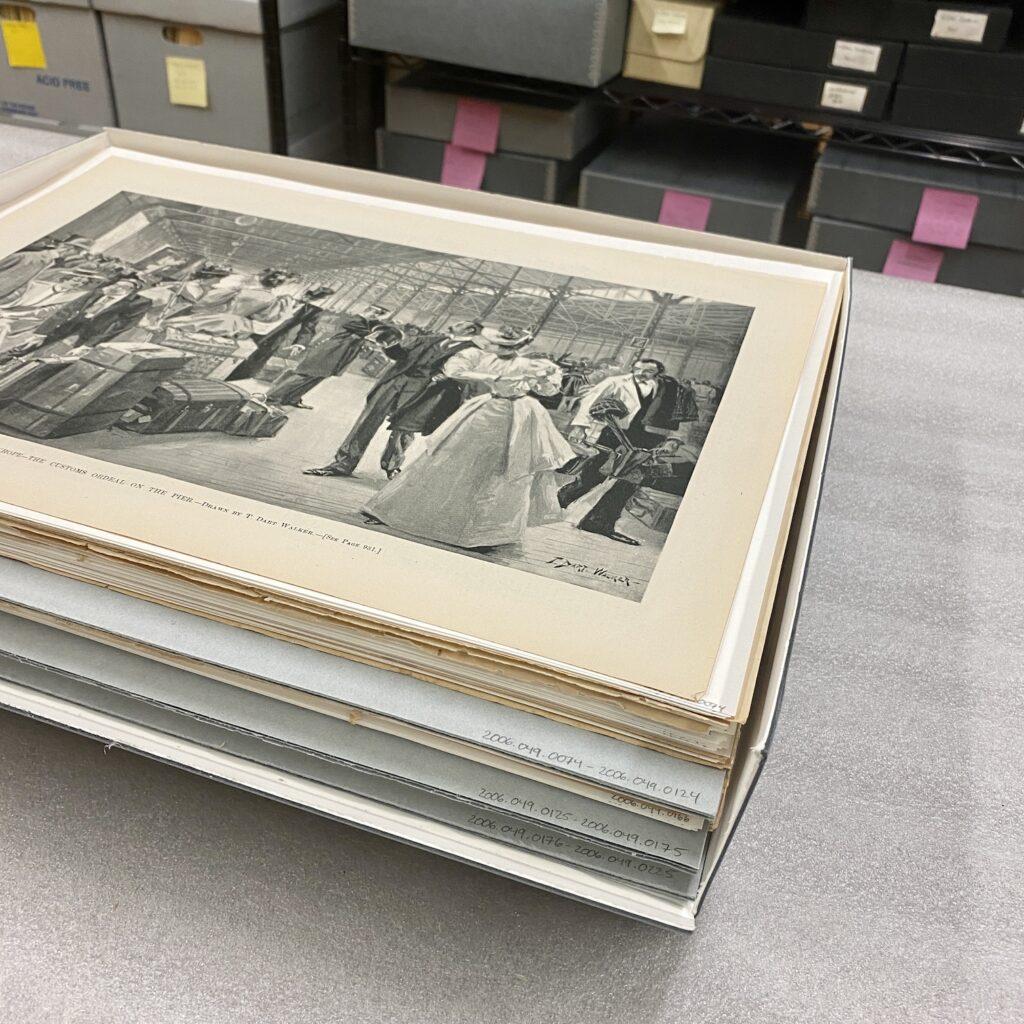

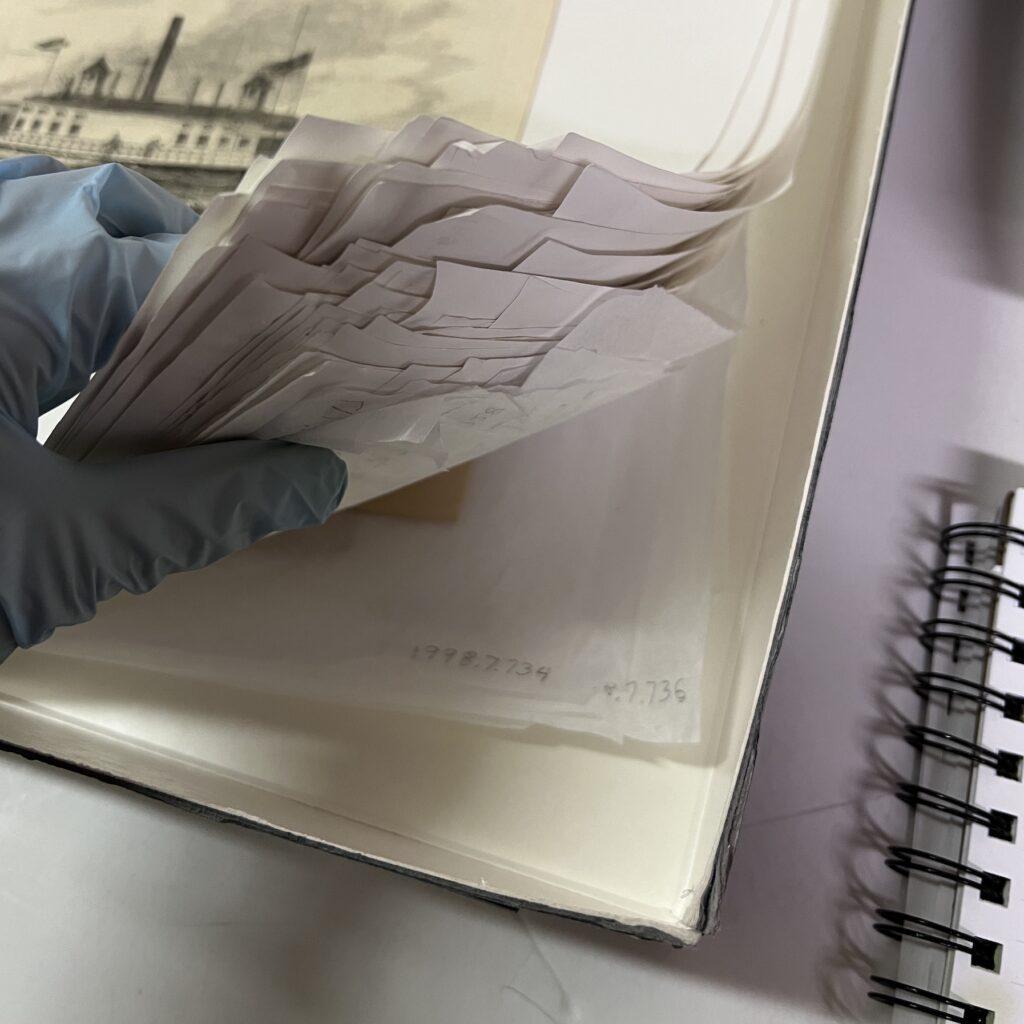

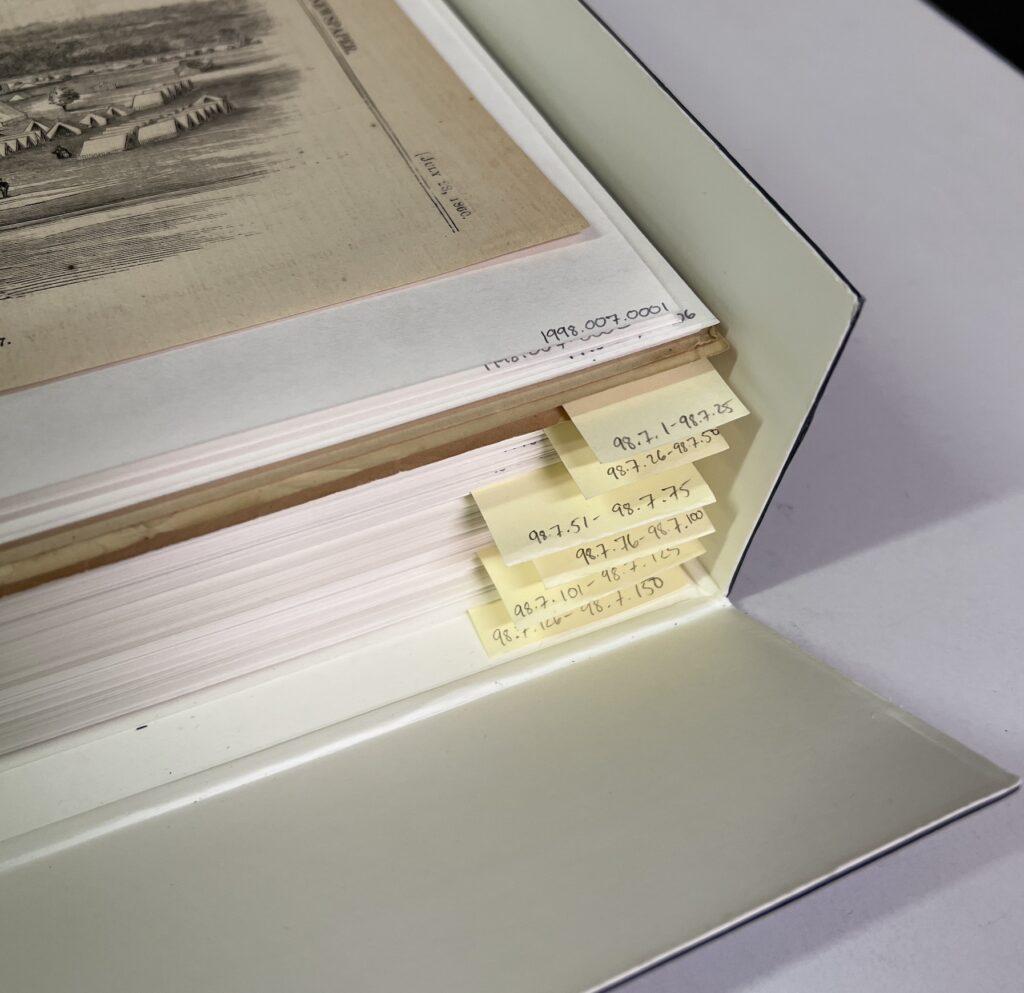

The cataloging and digitization of the newspaper clippings and illustrations started five years ago, with a passionate intern who took on the beginning of the first wall-to-wall inventory of all the individual sheets of paper located in the Museum’s works on paper collection storage area. After this first assessment, we worked on researching the context and provenance of each group of donations, did additional specific object condition assessment, defined preservation needs, and created a plan for the next steps.

Unfortunately, most newspapers printed in the United States since about 1850 are on poor-quality paper that was not made with preservation in mind. Their ephemeral nature meant that they have an expected lifespan of 50 years or less, and, as such, that they require special care and proper storage to extend their impermanent lifespans.

Our rehousing plan included storing them in new acid-free buffered materials, including boxes, interleaving paper, and creating lifting support with rigid boards for each 20 items to limit damages when handling. We looked for speciality boxes of all sizes, including specifically larger ones to allow them to be stored unfolded. Lastly, we plan to eliminate paper clips, staples, or tape as much as possible because they are all reasons for irreversibly damaging the materials.

Luckily, the Museum’s newspapers are already in a controlled environment, with almost no exposure to light and extremes of heat and moisture; however, if you have newspaper clippings that you are saving in your own home, know that damage from light is irreversible, and can cause not only fading of inks, but yellowing, bleaching, or darkening of paper. This really sweet video from our friends and colleagues at Duke University Libraries shows how to potentially do the whole process on your own.

Last, but not least, we concentrated on preserving the newspaper’s content, their images, and their data through digitization and cataloging.

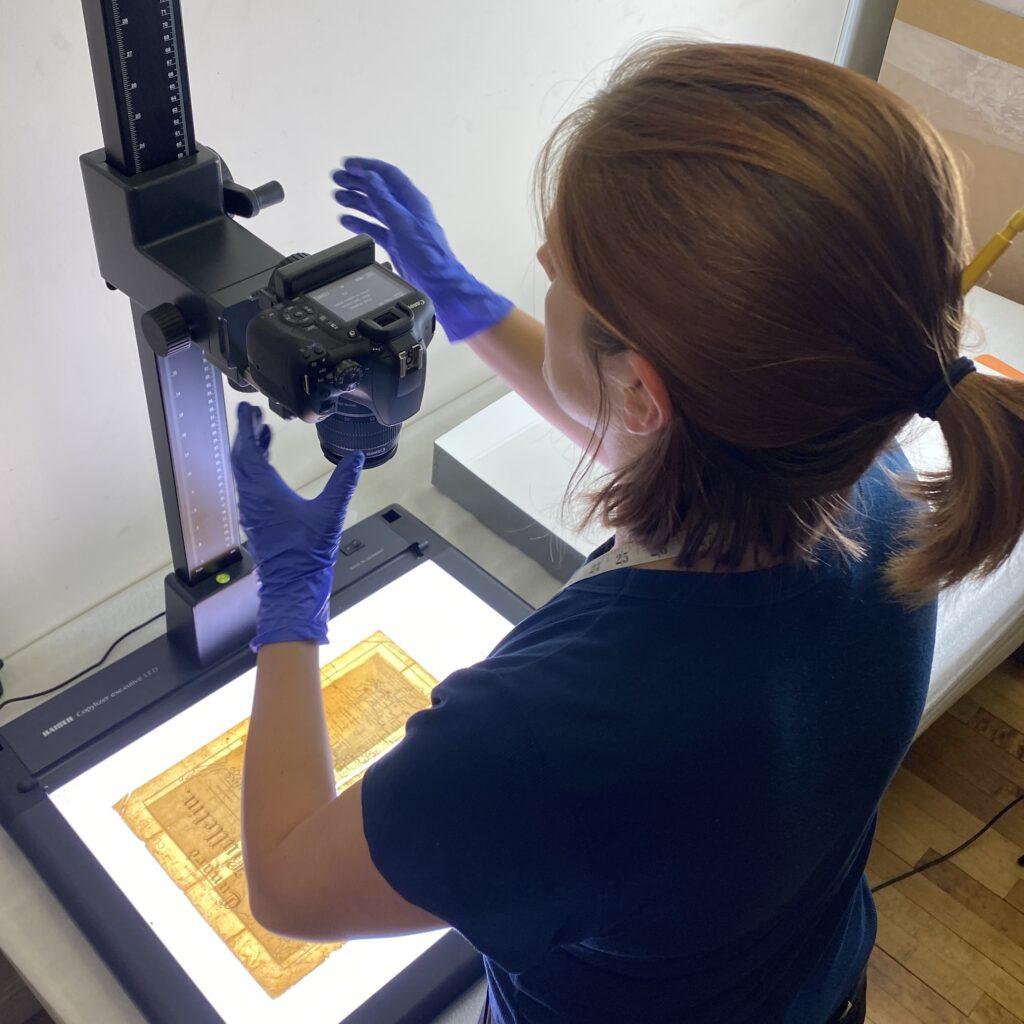

To prevent damage during imaging, and due to the sizes of newspapers, we decided that the safer approach was to use a hand-held digital camera, and occasionally, for smaller size clippings, using a scanner that can fully support the newspaper page.

With regards to their metadata, catalog records for these pages show many inconsistencies and reorganizing this information was a main focus of the past few months. Not having clear and consistent records for each clipping, could have jeopardized the entire project. Standardizing clippings’ creators, titles, and subjects allow us to find their information and their illustrations.

This inventory project adds preservation for future generations, as well as knowledge and accessibility to the collection allowing us to make everyone a better user of this important source material, whether the purpose is within the institution to prepare for an education program or walking tour, or the purpose is external, if they are for students who are writing a paper, if they are for individuals who are researching family history, or are looking to learn more about local history, and uncover facts and early perspectives on historical events.

The Seaport Museum’s collection is small, but mighty. After looking at our online selection, remember that your research could be aided by the microfilmed or digitized the Library of Congress’s Historic American Newspapers collection 1836-1922, or look to see if it is listed in the 1690–1922 American Newspapers Directory, available through your local library.

Additional reading and resources:

“Printing Newspapers 1400-1900: A Brief Survey of the Evolution of the Newspaper Printing Press” by Joanna Colclough, April 21, 2022. Library of Congress Blog. Accessed on June 16, 2023.

“Silhouette and Stereotype: Contextualizing Kara Walker’s Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated)” by Allison Robinson and Ksenia M. Soboleva, May 30, 2023. New-York Historical Society Blog. Accessed on June 16, 2023.

“The Fruits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture” by Shana Klein, University of New Mexico, May 1, 2015. Accessed on June 17, 2023.

“Basic care – Paper documents and newspaper clippings” Canadian Conservation Institute. Accessed on June 19, 2023.

“Caring for Private and Family Collections” Northeast Document Conservation Center. Accessed on June 19, 2023.

Acquisition Guidelines

The Seaport Museum’s Collection Management Policy, last revised in May of 2024, outlines the scope of the Museum’s collection, explains how the museum grows, cares for and makes collections available to the public, and clearly defines the roles of the parties responsible for managing these artifacts.