An investigation of printing history in mid-19th century Lower Manhattan

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

June 11, 2020

The South Street Seaport Historic District is located along the East River in Lower Manhattan, anchored between Wall Street and the Brooklyn Bridge. Today it is a tourist-friendly destination, home to the Seaport Museum’s historic ships, print shops, and galleries, as well as boat tours, shops and restaurants, and lively waterfront public spaces. But what fascinates and still attracts sailors, artists, businesses, urban planners, historians, archaeologists, and others—including myself—is the fact that today, like two hundred years ago, South Street is the emblem of New York City’s economy, continued transformation, and values. You can feel it just by walking on the streets, reading about the history of New York, and exploring museums and cultural organizations that preserve, interpret, and share historical records and artifacts about the city’s history.

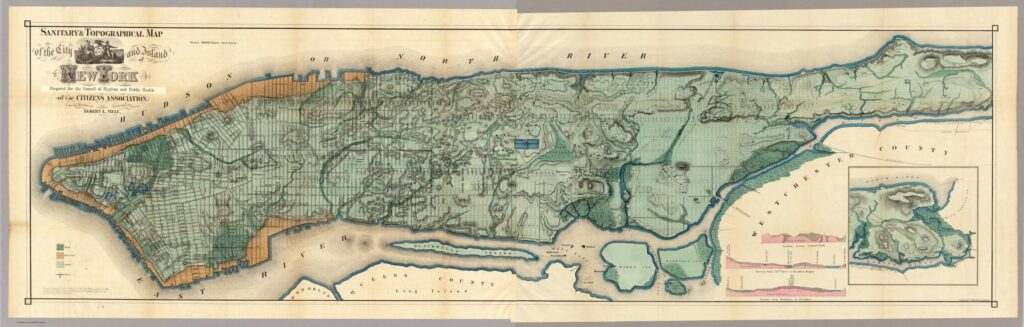

When I lead tours of the upper floors of Schermerhorn Row—the 1810-1812 counting houses that are the Museum’s main headquarters—I like to joke with visitors that they are walking on top of the of New Yorker’s garbage from 200 years ago. In the early 1800s, right in that spot they would have been in their swimming costumes in the East River. The land between Water, Front, and South Streets, which forms the heart of the South Street Seaport Historic District, was completely created by human activity between the 1790s–1820s, and the original Manhattan shoreline coincides roughly with current Pearl Street.

Land, especially waterfront land, has always been a premium real estate market in New York, and it was no different during the city’s early history, when merchants, ship owners, and shopkeepers were responsible for the city’s growth and richness.

The city had started to expand out into the East River already back in the 17th century, and there were a couple of reasons for this. First, the natural waterfront, with the original shoreline ships couldn’t dock right there. The shore was too shallow, and many trading ships would have to anchor in the middle of the river, all of the cargo would be unloaded onto rowboats, and then dragged ashore. Second, it was safer to dock on the southeastern shore of Manhattan than to attempt the more insidious western shore, where rocky reefs proved hazardous. In addition, since the East River was narrower than the Hudson it provided much-needed shelter for the small wooden early vessels. Third, and lastly, the city government, the Common Council of New York, saw a benefit to expanding out into the deeper water of the river in order “to make further improvements for the better convenience of trade and navigation and enlargement of the city and its buildings.” [1] PHASE lA ARCHAEOLOGICAL DOCUMENTARY STUDY, LOWER MANHATTAN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, FULTON STREET REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT, Prepared for AKRF, Inc., by Historical Perspectives, Inc., 2007. p. 21.

Because of these land-making practices, and the many incredible stories and examples of archaeological discoveries, you can just imagine what archaeologists and historians think of South Street. The neighborhood is indeed one of New York’s richest archaeological areas, and a mecca for anyone who wants to study the past, using the objects people have left behind underground.

In the last forty years, the focus of archaeological activities in New York City has shifted from life before the city was created, and sites associated with the Revolutionary War, to the study of the city itself. Most archaeological work today is completed by professional archaeologists in response to proposed construction projects under the oversight of the New York City’s Landmark Preservation Commission (NYC LPC), following city, state, and federal laws. This type of work is called cultural resource management (CRM) and is carried out in accordance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.

Recent Acquisition and Printing History

Between 2009 and 2016 Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, Inc. were contracted to serve as the cultural resource management consultant on two infrastructure improvement projects located within the South Street Seaport Historic District, under the supervision of NYC LPC.

Upon completion of the excavation projects, NYC LPC retained the most significant artifacts at The Archaeology Repository which curates the city’s archaeological collections and to make them accessible to archaeologists, researchers, teachers, students, and the public. Many of the redundant materials are usually culled before collections go to the Repository, and those culled materials can be transferred to educational facilities and other cultural organizations who want them, along with information about where they were excavated (provenience).

In 2019 the South Street Seaport Museum was offered a donation of glass ink and mucilage bottles from a large deposit that was found in situ at 65 Fulton Street and Cliff Street, excavated by Chrysalis.

When I received the offer of this donation I was literally over the moon. It seems that we hit a jackpot of acquisition criteria all at once. These bottles are strictly tied to the history of lower Manhattan and the people, commerce and work that have contributed to the history of New York City’s world port, which is at the core of our mission and vision.

These artifacts were excavated following NYC LPC standards and guidelines, and last, but not least, these items could aid and enhance the interpretation of the connection of printing history, and our print shops, to the overarching Port of New York.

At the time, the Museum didn’t not have archaeological items dated to the mid-nineteenth century from the South Street Seaport Historic District, as our well-known collection of major archaeological artifacts was deaccessioned and transferred to the New York State Museum in 2005.

After the Collections and Curatorial Committee at the staff level reviewed the offer, and proposed the acquisition, our Board’s Collection Committee discussed it, and when approved, I, as Senior Registrar at the Museum, catalogued and documented the objects.

Cataloging and documenting archaeological artifacts is slightly different than our usual type of objects, but we were lucky to have a professional archaeologist on staff that helped us with nomenclatures and jargon of the practice.

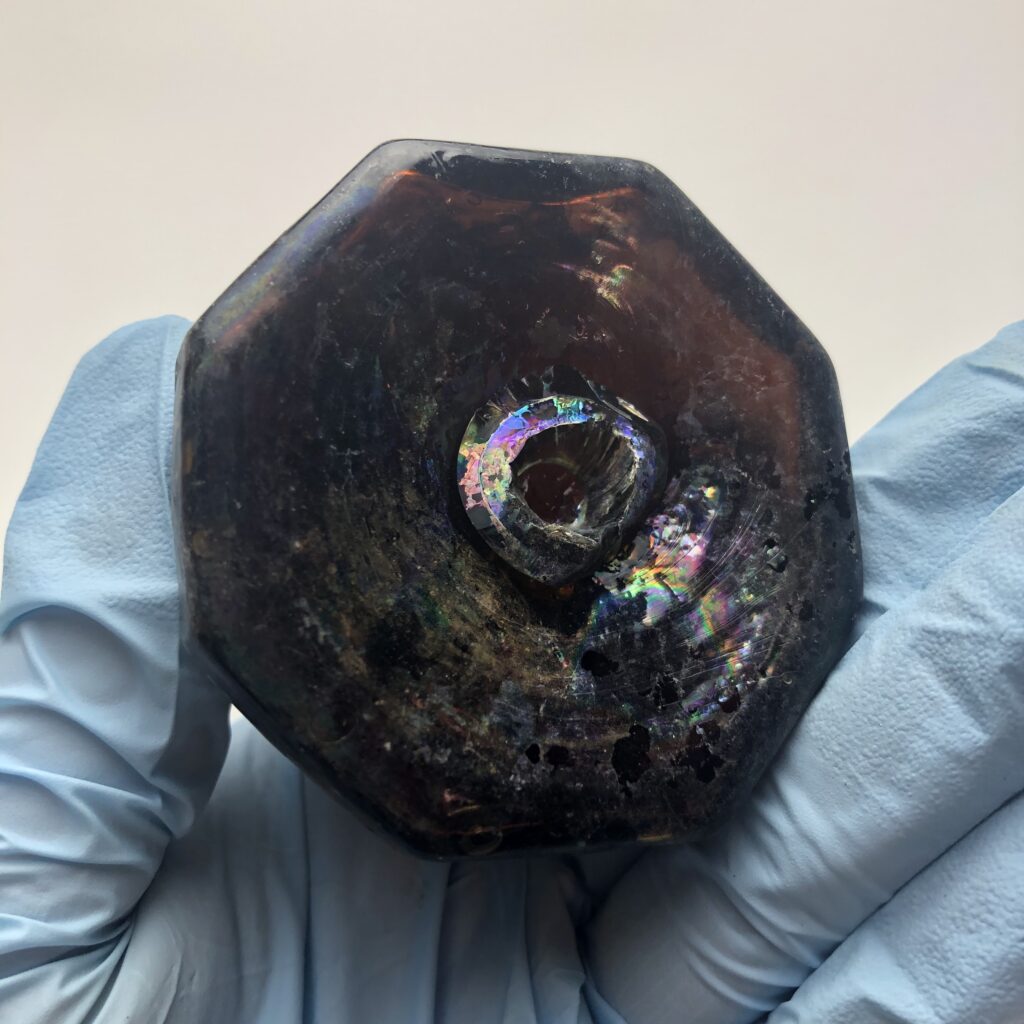

The majority of the smaller bottles (38) are eight-sided glass umbrella ink bottles, either olive or aqua glass color, with pontil scars on their bases and rolled finishes, a form produced between 1860 and 1880. Bottles are embossed with writing on the side panels with either a single “R” or “M & P” on one side, or “M & P” and “NEW YORK” on separate panels.

The other five (5) bottles are clear glass decagonal paneled bottles used for mucilage, a type of glue, and the last five (5) are glass master ink bottles, used to fill smaller inkwells.

What was fascinating was the fact that:

- A few bottles also had the remains of their corks and liquid sealed inside.

- A few mucilage bottles had some remains of their paper label mentioning “Murphy’s Expressly Prepared Mucilage.”

- The initials in the umbrella-style ink bottles are most likely tied to either the manufacturer or the company that would have used these bottles.

- We compared art handling, describing artifacts, and housing objects from both a museum registrar’s point of view, and an archaeologist’s perspective.

The stories behind these bottles

After this first cataloging process, curatorial research came, and it is often one of most fascinating parts of my job. It’s rewarding and particularly intriguing researching additional provenance, and unfolding objects’ history and mysteries.

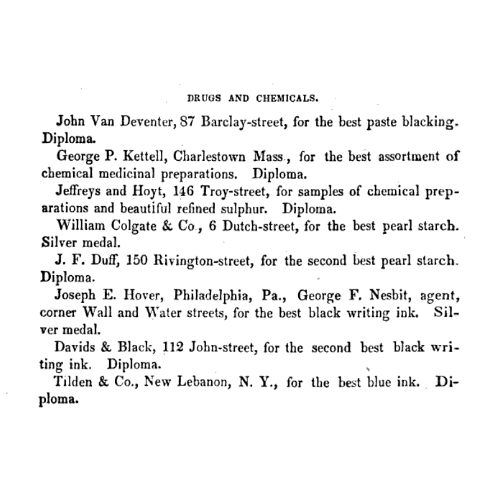

Historic records show that a contemporaneous print shop was located in the same area as the bottle deposit, property of Thaddeus Davids and John Black. The two men had an ink company at 112 John Street in the 1840s and early 1850s. The 1848 Annual Report of the American Institute of the City of New York also stated that the Davids & Black company was selling “the best red ink and copying ink,” “beautiful specimens of sealing wax,” and “the second best black writing ink in the city.” [2] American Institute of the City of New York, 1848, p. 79, 84, 85.

By the mid-1850s, when Black died, Davids had offices and a stationer’s business at 22 Cliff Street around the corner from 65 Fulton Street.

By 1861, 65 Fulton Street was the property of D. Murphy’s Sons Company , and their stationer’s store operated at 372 Pearl Street.[3] Trow’s New York City Directory. Vol. LXXIV. John F. Trow Publisher. New York, New York, 1860, p. 625. But Murphy’s printing business was established in 1828! [4]J. Arthurs Murphy & Co., Reference book and directory of the book and job printers, newspaper, magazine, and book publishers, also paper manufacturers and paper warehouses. New York, 1871-1872, … Continue reading

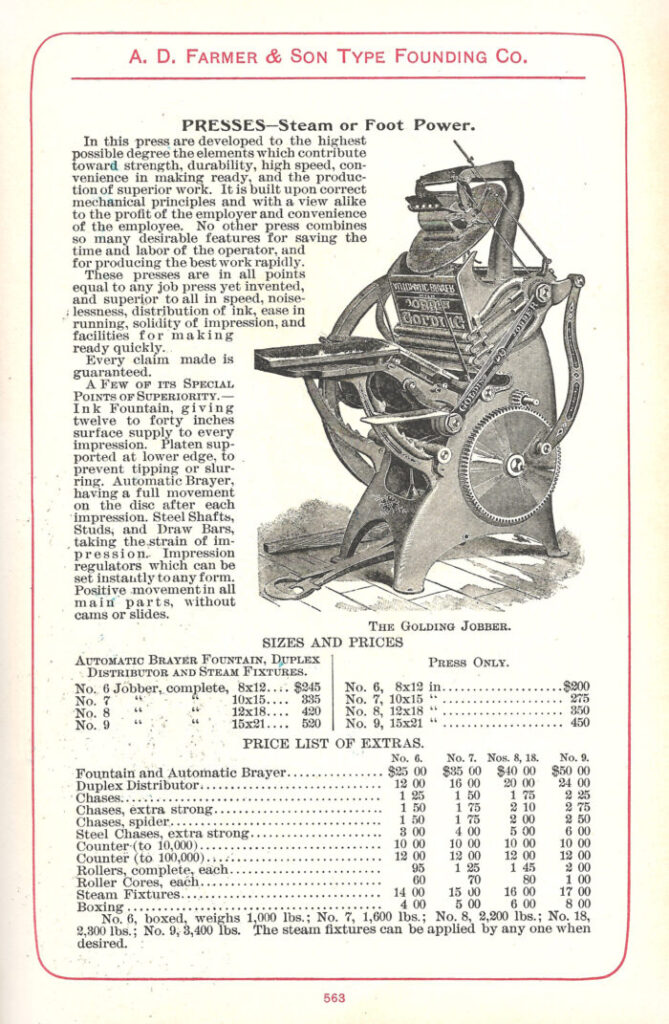

By the 1870s Murphy was most likely a successful printer as he was able to afford expensive machinery needed for steam printing. Murphy’s business printed a publication in 1876 that designates him as a “steam printer”. [5]Steam printing was invented in the 1820s and enabled faster and more efficient presses, but it was not widely used until the 1850s. From James Moran, “Printing Presses: History and Development … Continue reading The printing business was also described in the 1871-1872 Reference Book ad Directory of the Book and Job Printers, as “extensive” with “six presses.” [6]J. Arthurs Murphy & Co., Reference book and directory of the book and job printers, newspaper, magazine, and book publishers, also paper manufacturers and paper warehouses. New York, 1871-1872, … Continue reading

Last, but not least, I was able to find out that Murphy’s Sons also bottled their own mucilage, an adhesive used with paper products such as stamps, envelopes, and labels, which explain our mucilage bottles’ labels.

By 1912, the Printing Trade News reported that a different printing business, the Brieger Press, was contemplating leaving 65 Fulton Street, suggesting they had been there for some years. So, are these bottles from the time Walter Murphy’s business moved out of 65 Fulton Street around the turn of the 20th century? Or were items disposed of during Murphy’s time of operations when he switched to steam printing and his inventory was becoming obsolete? Either way, the bottles recovered during this excavation are remnants of the Murphy family’s successful print and stationery business.

These questions, and additional research for exhibitions and education programs are the exciting part of collection management, registration, and collection access. The goal of museums and archaeology is to study and to share the past using the objects people have left behind. This knowledge plays an important and critical role in preserving our cultural and anthropological heritage.

Suggested readings and resources about New York City’s Archaeology and the South Street Seaport Historic District:

- SOUTH STREET SEAPORT HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION REPORT, The City of New York, Landmark Preservation Commission, 1977.

- Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Anne Marie Cantwell and Diana diZerega Wall, Unearthing Gotham: The Archaeology of New York City, Yale University, 2001.

- Russell Shorto, The Island at the Center of the World, Random House, 2005.

- Burling Slip Bulkhead Documentation Report, Prepared for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, by AKRF, Inc., 2011

- Guidelines for Archaeological Work in New York City, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), 2018.

- About The NYC Archaeological Repository, The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center collections, education resources, ideas for teachers, and digital exhibitions.

- About the New York State Museum Archaeology Department’s collections, departments, researches, and news.

Explore the Collections

Through the new and improved Collections Online Portal, you can explore highlights from the various collections within the Museum. Whether items are preserved in storage, displayed in Museum galleries, or on loan to fellow institutions, you can digitally discover some of these special objects in digital format.

References

| ↑1 | PHASE lA ARCHAEOLOGICAL DOCUMENTARY STUDY, LOWER MANHATTAN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, FULTON STREET REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT, Prepared for AKRF, Inc., by Historical Perspectives, Inc., 2007. p. 21. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | American Institute of the City of New York, 1848, p. 79, 84, 85. |

| ↑3 | Trow’s New York City Directory. Vol. LXXIV. John F. Trow Publisher. New York, New York, 1860, p. 625. |

| ↑4, ↑6 | J. Arthurs Murphy & Co., Reference book and directory of the book and job printers, newspaper, magazine, and book publishers, also paper manufacturers and paper warehouses. New York, 1871-1872, p. 20. |

| ↑5 | Steam printing was invented in the 1820s and enabled faster and more efficient presses, but it was not widely used until the 1850s. From James Moran, “Printing Presses: History and Development from the Fifteenth Century to Modern Times,” University of California Press, 1973. p. 123. |