Dozens of voyages, hundreds of memories

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

April 1, 2021

The collections and archives of the South Street Seaport Museum hold many ship’s logbooks, travel diaries, and scrapbooks. These objects are precious because, along with being beautiful or containing records of historic events, these primary accounts include the “voice” of people who lived in the past. Reading words printed onto the page of a history book has a different impact than reading words handwritten onto the page of a personal journal. There is a human connection that is hard to replicate in even the most detailed historical interpretation.

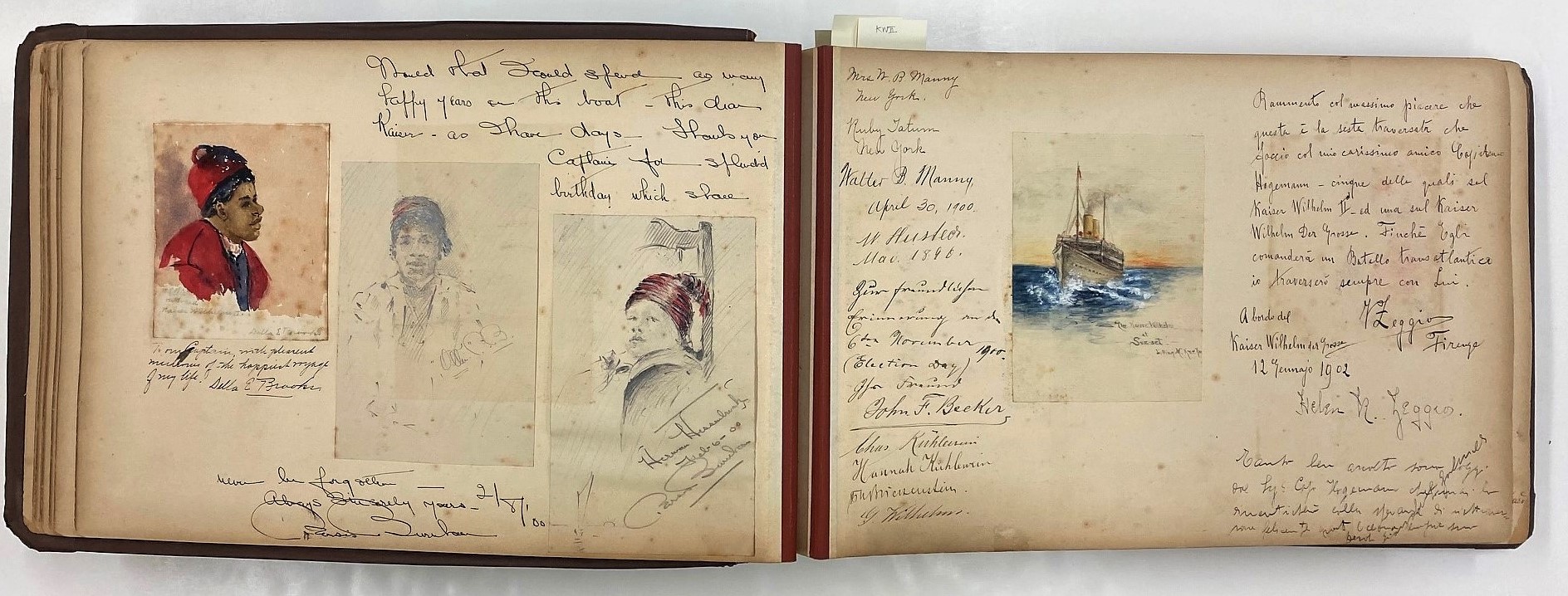

The Museum recently acquired a personal autograph book that touches on hundreds of notable people from the early 20th century. This book belonged to Kapitän Dietrich Högemann (1852–1917), the Commodore of the North German Lloyd Line (NDL) who commanded 163 voyages across the Atlantic Ocean of some of the most famous ocean liners of his day. The book’s pages are full of messages and notes, lyrics and poems, drawings and artwork done by the passengers on these journeys. These passengers included European nobles, American magnates and socialites, famous artists, performers, journalists, scientists and politicians.

Captain Högemann’s time as an ocean liner captain aligns with the heyday of passenger travel across the North Atlantic. From 1900 to 1914, nearly 13 million people immigrated to the United States by ocean liner, most of whom passed through New York Harbor and Ellis Island. Also during this time the wealthiest American citizens and the European elite were travelling on board the same ships to vacation or to take care of business matters on both sides of the Atlantic. The opulence of First Class ocean liner travel during the early 20th century still captures the imagination— many people think of the sinking of the RMS Titanic in terms of the beauty of the ship or its wealthy, famous passengers.

Though our collections and archives include thousands of items related to ocean liner travel and its part in the rise of New York City as a financial and cultural capital, Captain Högemann’s book is in part special to the collection because it comes from an ocean liner captain. The ship’s captain is the ultimate authority on their vessel; they are responsible to the passengers and crew to keep them safe and comfortable, as well as to the shipping line to manage the company’s most valuable asset. The captains of ocean liners— ships that carried thousands of people and cost millions of dollars to construct and operate— were a professional elite.

As the commander of his ship, and later the Commodore of the whole North German Lloyd Line fleet, Captain Högemann was a celebrity both on his ships and on land. His last voyage before retirement in 1913 warranted an article in The New York Times that included his portrait and biography. His death in 1917 was also printed in the newspaper.

Captain Högemann’s book showcases how he, and other ocean liner captains, associated with their passengers travelling in First Class and members of transatlantic high society. Before we look at a selection of the notables included among the hundreds of inscriptions inside this incredible object, let’s quickly set the scene:

The Ships

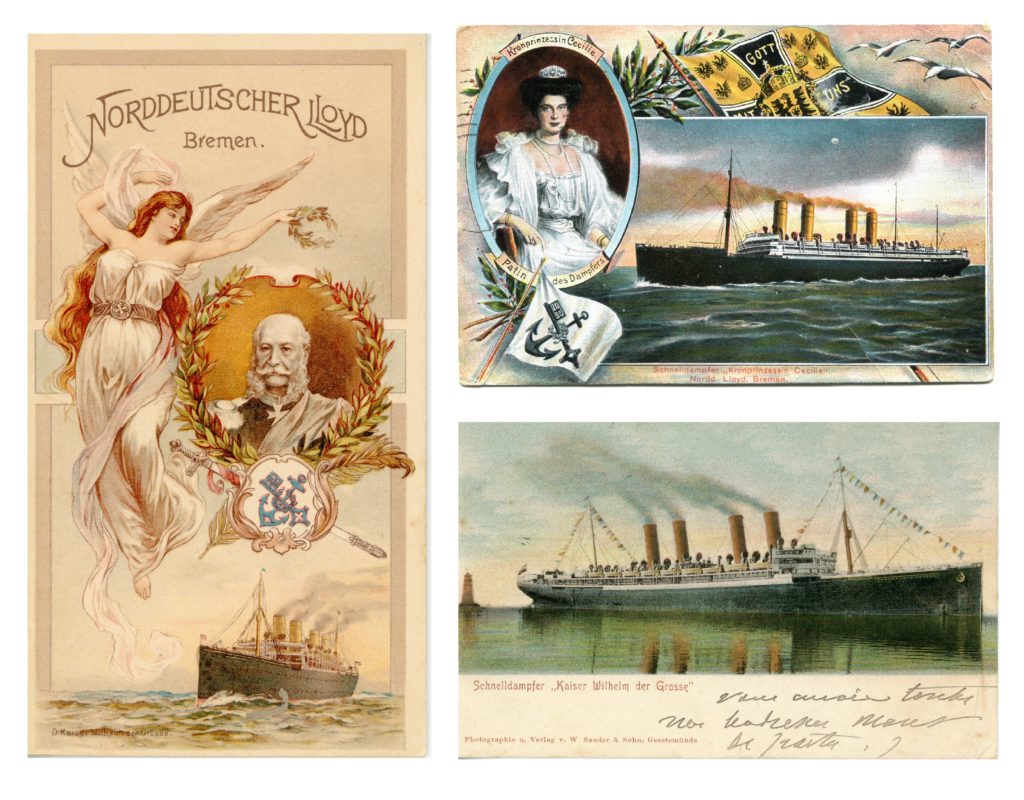

These examples of ocean liner ephemera are available on the South Street Seaport Museum’s new Collections Online Portal

Captain Högemann commanded many vessels during his 44 years at sea. His autograph book covers the years between 1899 and 1913, and includes entries from voyages aboard SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, SS Kaiser Wilhelm II, and SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie.

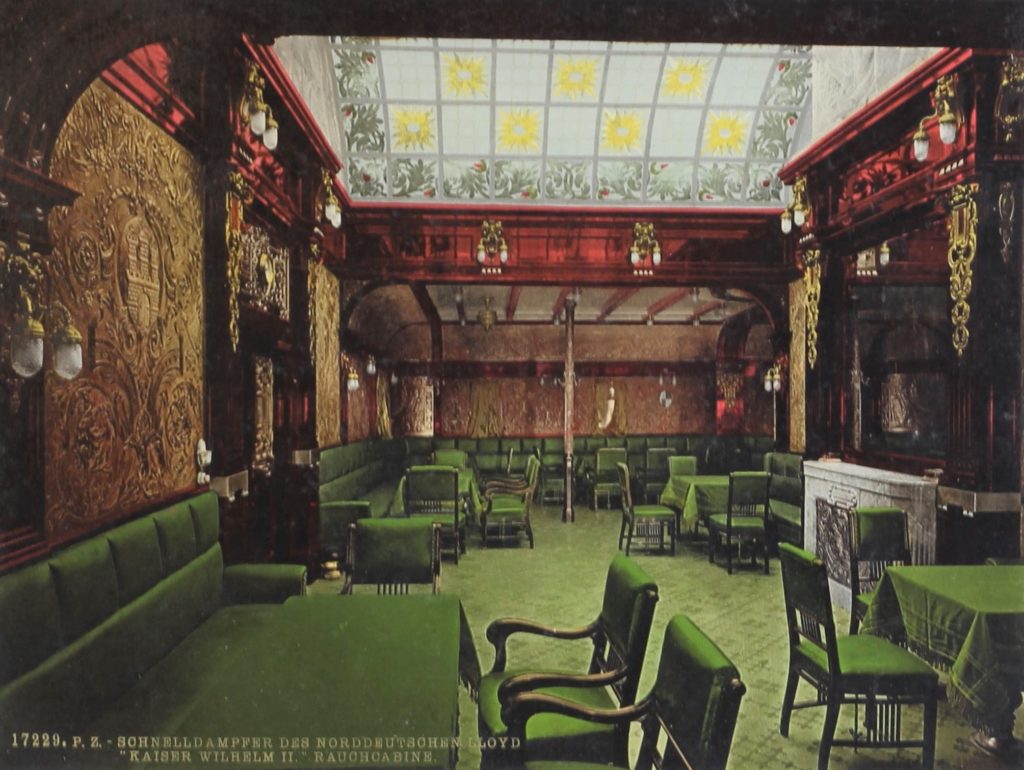

Launched in 1897, SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse ushered in a new era of luxury transatlantic travel and marked the North German Lloyd Line’s intention to surpass their British competitors— the White Star Line and the Cunard Line. Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse immediately stood out from other transatlantic ocean liners since it was the first to have four funnels. The ship’s speed, size, and accommodations proved successful with travellers and the North German Lloyd would launch three sister ships by German shipbuilder Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin: SS Kronprinz Wilhelm in 1901; SS Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1902; and SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie in 1906. The latter ships were a bit larger than Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and could carry over 1,800 passengers.

The four “Kaiser-class” liners were known for their luxurious First-Class interiors. Architect Johann Poppe (1837-1915) was largely responsible for the interior design of the ships and developed a Baroque style that borrowed decorative elements from a variety of historical periods. First-Class cabins and public rooms were heavily ornamented, with ample fine woodwork, velvet, and gilt.

Inside the Book

So who were the people who travelled in First Class on board Captain Högemann’s ships? There are hundreds of individual messages and signatures within Captain Högemann’s book. Below are just a few of the most recognizable names within:

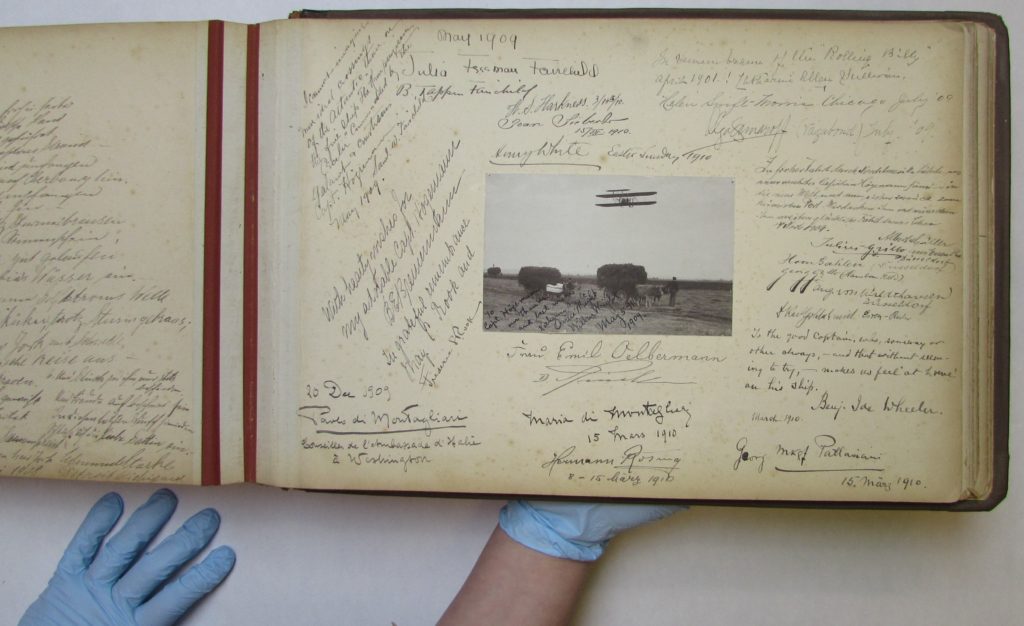

Many of the people in the book that are still known today are remembered for innovating some of the most significant technologies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The page above includes a small photograph of an early airplane flying over ox-drawn haycarts. The well wishes below are signed by the aviation pioneers Orville (1871-1948) and Wilbur Wright (1876-1912), and their sister Katharine Wright (1874 -1929). The Wrights were returning to the US in May 1909 after a successful tour of France, Italy, and Germany with their “flyer.”

Other famous inventors in Högemann’s book include Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937), the Italian engineer credited with developing long-range radio communication, and American electrical engineer George Westinghouse (1846-1914), whose high-voltage alternating current (AC) competed with Thomas Edison’s large-scale low-voltage direct current (DC) for supremacy in the early days of electrical power.

Along with inventors, Högemann’s book includes political figures and intellectuals; Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) did not date his message “In remembrance of two very pleasant voyages across the Atlantic with Captain Högemann”, but the African American educator and political leader is known to have taken a European vacation in 1903. As biographer Louis R. Harlan wrote, it was “one of the few genuine vacations he ever had, at the age of forty-seven.”

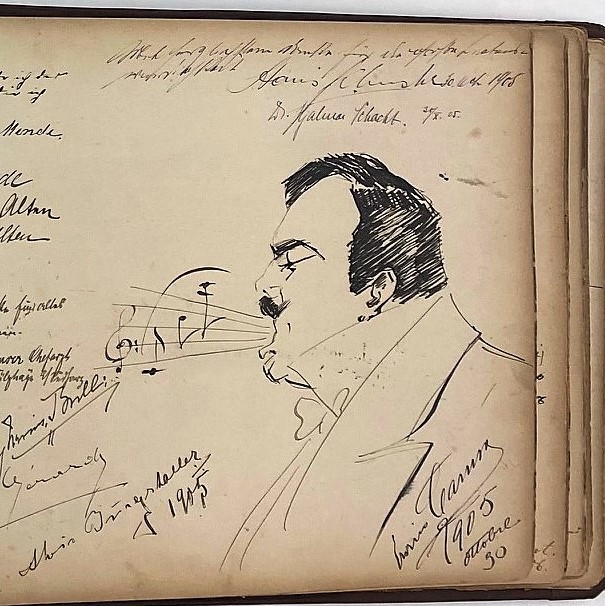

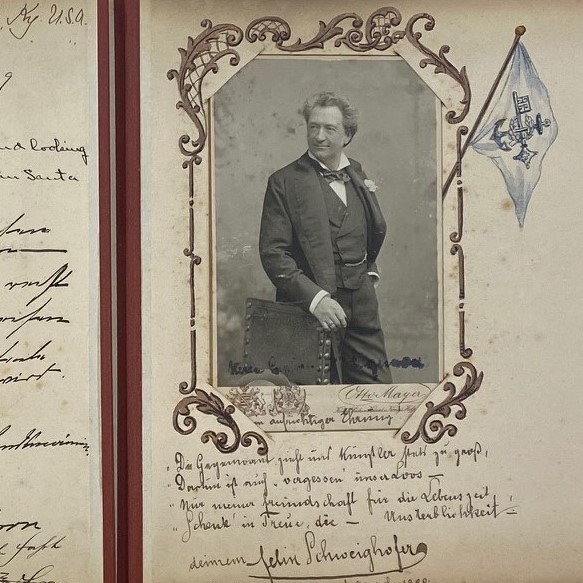

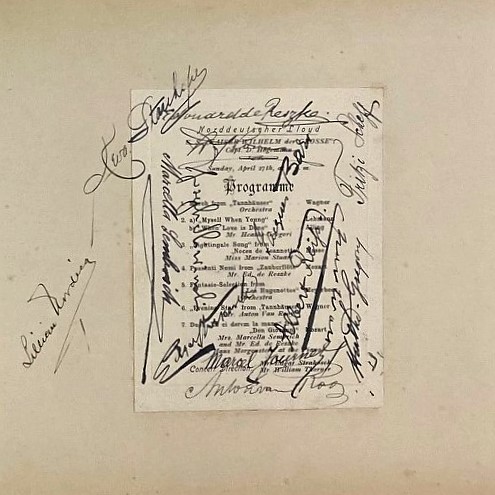

Musicians and actors can be found throughout Högemann’s book as performers often crossed the Atlantic while on tour. The signature of Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso (1873-1921) includes a sketch of the tenor’s powerful voice. Polish soprano Marcella Sembrich (1858-1935) actually performed for her fellow passengers while on board SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, and then signed the music programme pasted in the book. Austrian actor and singer Felix Schweighofer (1842-1912) included a portrait photograph and a small sketch of the North German Lloyd Line’s flag.

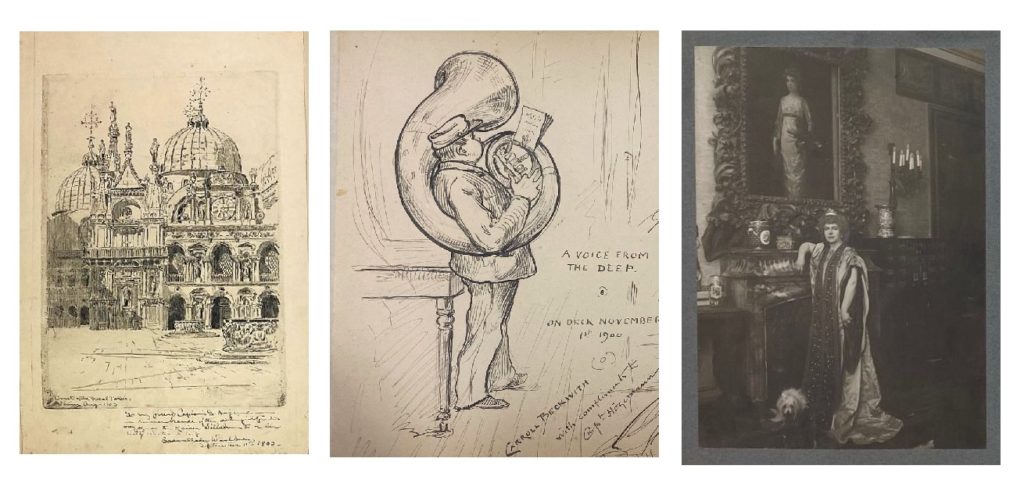

Visual artists contributed some of the most stunning additions to the book. Cadwallader Lincoln Washburn (1866-1965), an artist who became deaf from the age of five, added a page-size sketch of the court of the Ducal Palace in Venice. James Carroll Beckwith (1852-1917) took inspiration from the voyage itself and drew a tuba player performing on one of the ship’s decks with the caption “A voice from the deep.” Portrait painter Princess Elisabeth Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy (1863-1923) may not have sketched something for Captain Högemann, but she did include a photo of herself posing with one of her paintings.

Of course, some names in Captain Högemann’s book are largely remembered as belonging to some of the wealthiest American families during the Gilded Age. George Jay Gould (1864-1923) and his wife Edith Gould (1864-1921), Grace Vanderbilt (1870-1953), and Daniel Guggenheim (1856-1930) all graced Captain Högemann with their signatures. John Jacob Astor IV’s (1864-1912) undated signature was dashed across one page, likely not long before he died during the sinking of RMS Titanic.

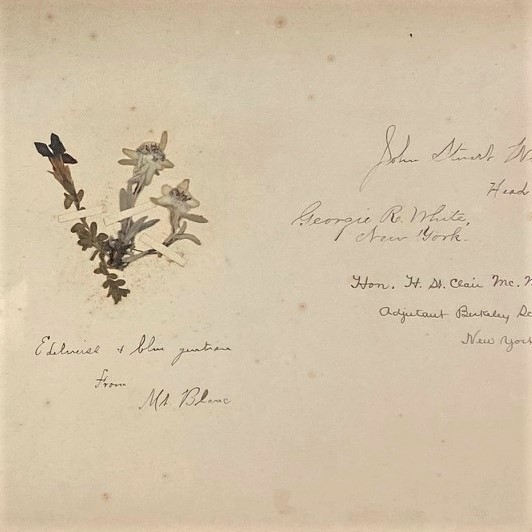

Of the thousands of passengers in First Class that Captain Högemann took across the North Atlantic, not all are noted in history. Some of the most interesting entries are from passengers whom we know little, or even nothing, about. One passenger added a pressed edelweiss bloom from Mount Blanc. One painted a view of the Hudson River piers along Hoboken, New Jersey, from where the North German Lloyd ships departed. Another captured a scene on the ship’s deck and painted a woman reading in a deck chair, wrapped in a blanket to stave off the ocean breeze.

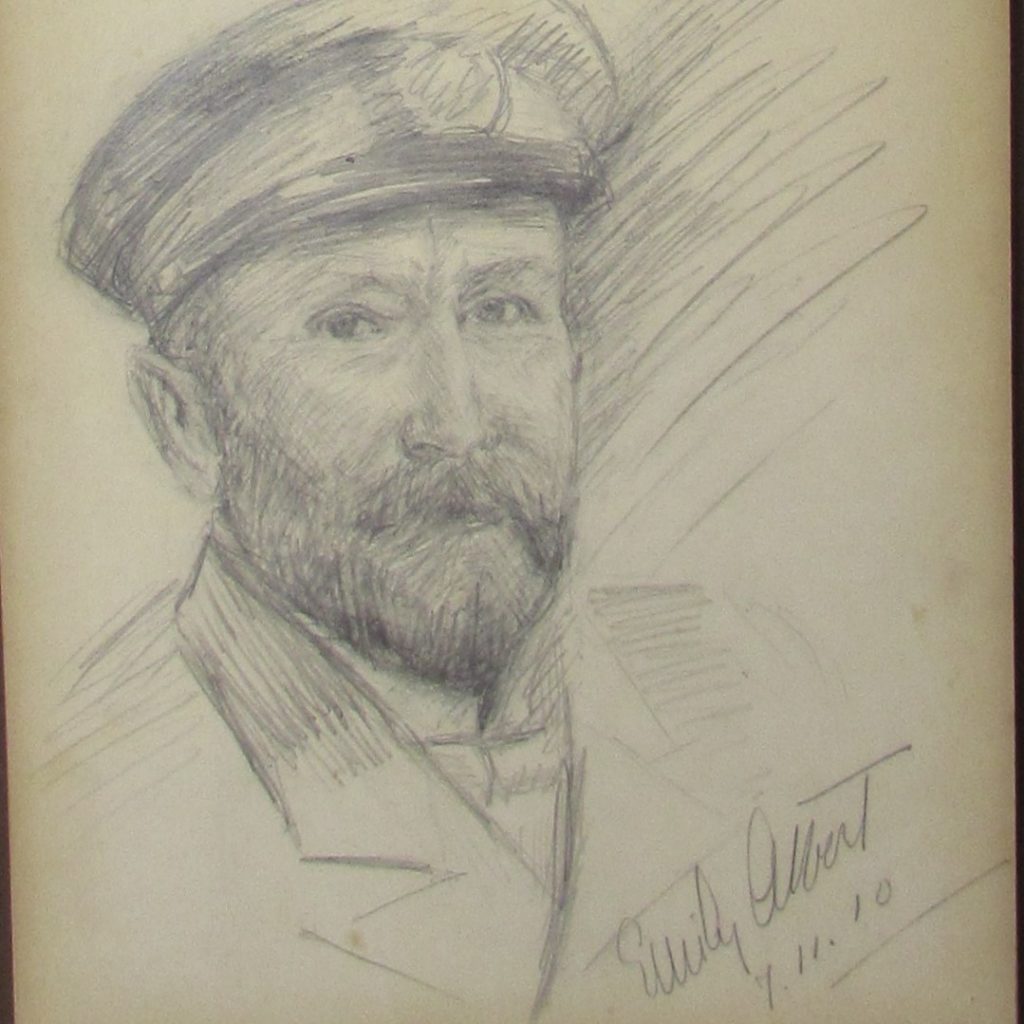

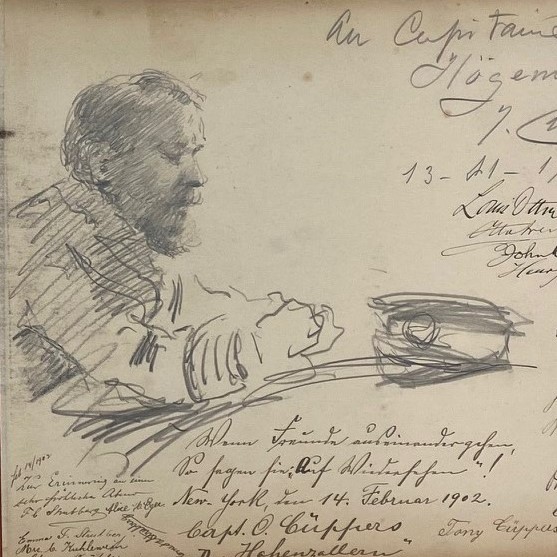

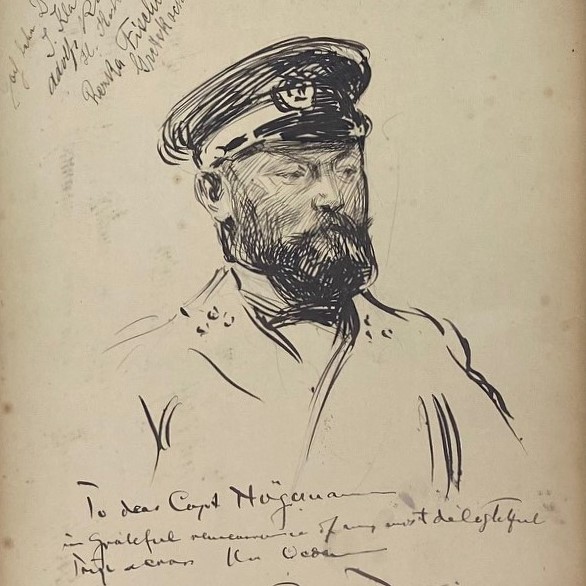

Captain Högemann was a popular subject for the artistically inclined passenger. The book includes several portraits of the commander with his captain hat, embodying the gentlemanly gravity expected of an ocean liner captain.

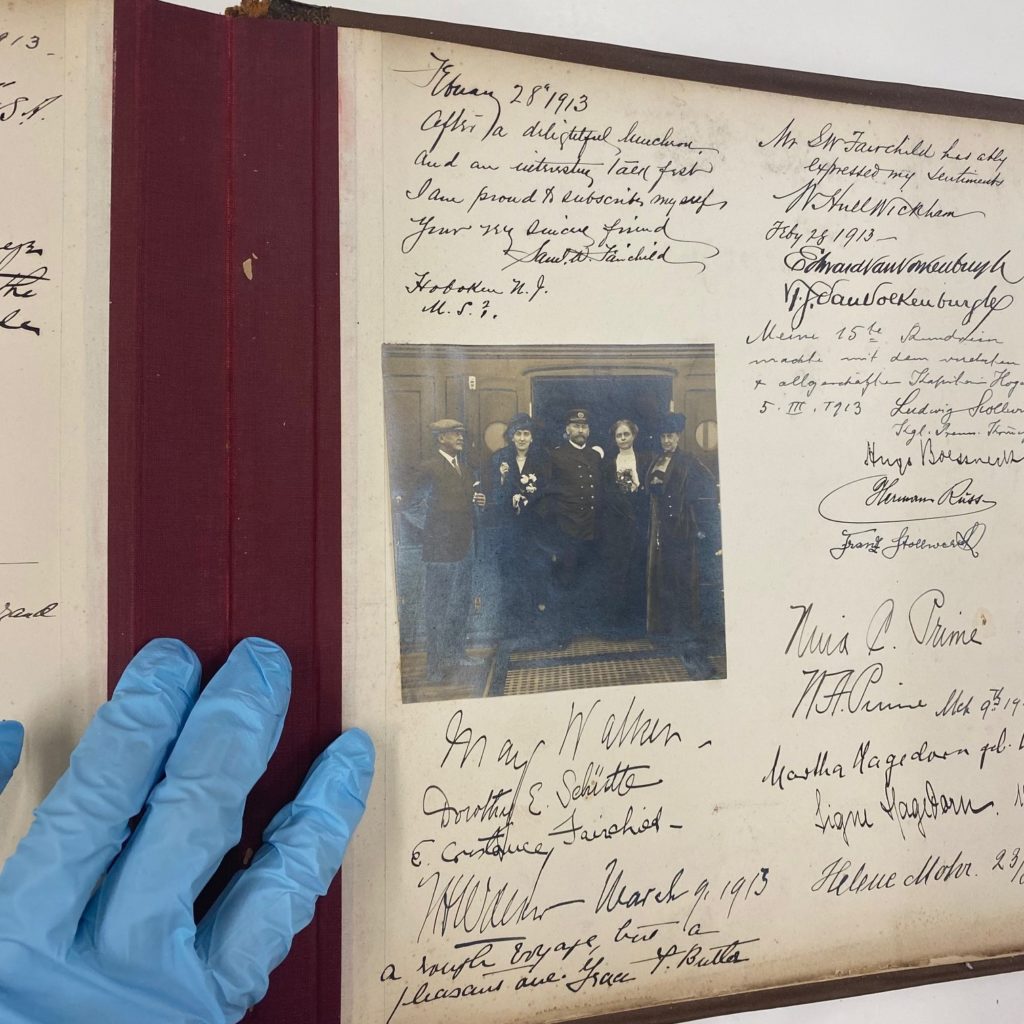

On one of the last pages of his book, Captain Högemann added a photograph of himself on what appears to be a ship’s deck. The surrounding notes and well wishes are dated to March and April 1913. On May 6, 1913, after arriving with his ship SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie, it was announced that Captain Dietrich Högemann would be retiring after his long career at sea. When interviewed by The New York Times, the 60-year-old Högemann stated: “The Directors asked me to stay another year, but I am going to retire now and enjoy a few years ashore and learn what it is to sleep every night in a comfortable bed without an officer knocking at the door and saying it is foggy or something else, to call me to the bridge.”

Captain Högemann’s retirement was only a year ahead of the outbreak of World War I. The conflict marked the end of transatlantic ocean liner travel as it had been, as many of the great liners were destroyed during the war and immigration to the United States never again reached the levels seen in the first decade of the 20th century. Captain Högemann’s book remains as a small glimpse into the dazzling world of the prewar transatlantic elite.

Sources and additional readings

“Lloyd Commodore to Live on Land” The New York Times. May 7, 1913.

“Captain Deitrich Hogemann” The New York Times. May 19, 1917.

The Sway of the Grand Saloon: A Social History of the North Atlantic by John Malcolm Brinnin, 1971.

Booker T. Washington by Louis R. Harlan. 1983. p. 282.

“S.S. Kronprinzessin Cecilie” Mahler Foundation.

“Demonstrations in Europe” The Wright Brothers Exhibition. Smithsonian Air and Space.