20th century Queer History in the Maritime World

A Blog

By Zak Risinger, Director of Engagement and Public Programs

June 1, 2024

Zak Risinger, Director of Engagement and Public Programs at the South Street Seaport Museum, spearheads the Museum’s public programming with the goal of expanding offerings to more inclusively represent the voices and stories of all New Yorkers. One significant initiative under Risinger’s leadership is the Queer History series, designed to share underrepresented queer narratives from both the past and the present, year-round. In this blog post, Risinger delves into how he develops programs for the Queer History series and explores queer culture from the early to mid-20th century.

It Starts with a Spark

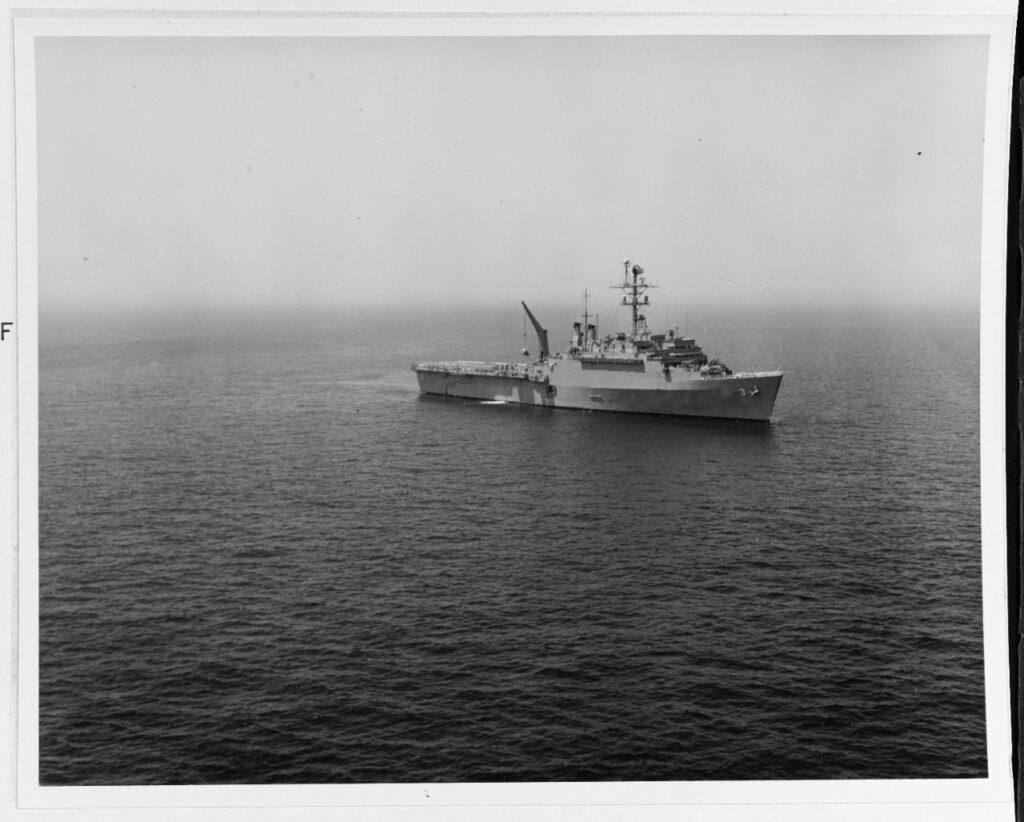

I am constantly on the lookout for new topics that highlight the rich queer history of New York and the waterfront. Sometimes I come across amazing tidbits of queer history that might not lead to a full program, but are too good not to share. Recently, I attended the Council of American Maritime Museums (CAMM) conference where I learned about the USS LaSalle, which has been called “the gayest ship in the Navy” because about 60% of its 500-person crew was thought to be gay.

Left: USS LaSalle lifting a mock-up space capsule during tests of her ability to handle space recovery missions, off Lynnhaven inlet, Norfolk, Virginia, June 7, 1966. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Right: USS LaSalle underway, with seven SH-3 Helicopters parked AFT, November 1966. Naval History and Heritage Command.

It turned out that the USS LaSalle might not lead to a stand-alone program. You can’t win them all. What could I do next? Previous events in the Museum’s Queer History series have already covered the 1960s through the 1990s––events through May 2024 are highlighted at the end of this article. During the aforementioned CAMM presentation by the American Merchant Marine Museum, I learned more about the lives of queer individuals in the Navy and Merchant Marine in the 1950s, particularly those with strong ties to New York. Recently, I was glued to the new, award winning mini-series, Fellow Travelers, starring Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey (two openly gay actors portraying queer characters) that traces the four-decade-long love story of two men who met in Washington, D.C. under the shadow of 1950s McCarthy era. This seemed as though the universe was calling me to do more research into 1950s queer history for a possible future public program at the Museum. Whether or not this research leads to something more, now seems like the perfect time to explore this snapshot of queer history in America.

Queer Culture in the Armed Forces in 1930s and 1940s

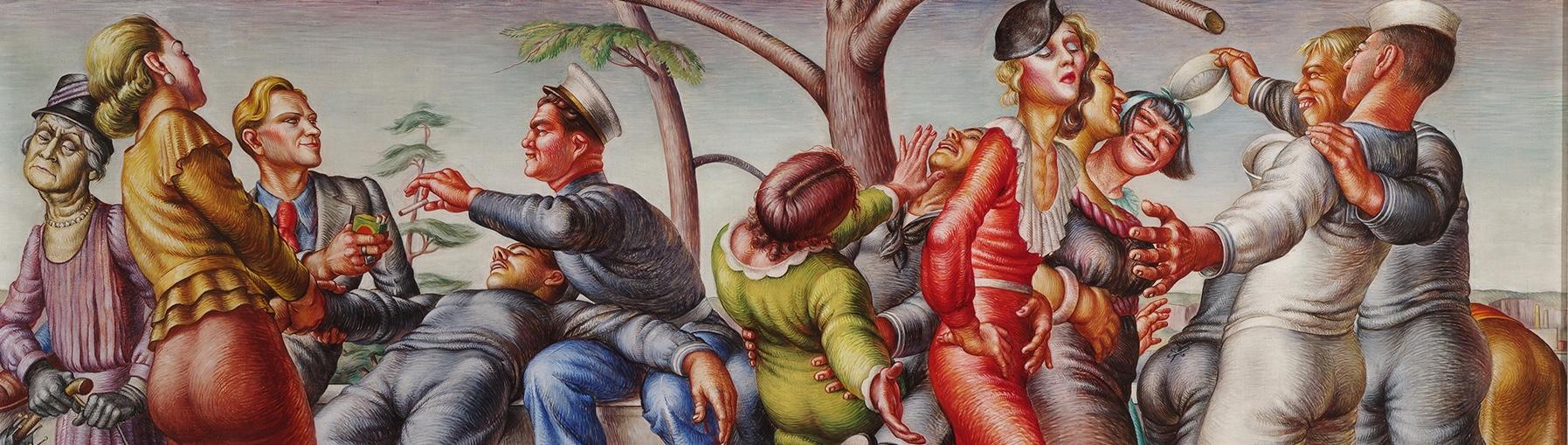

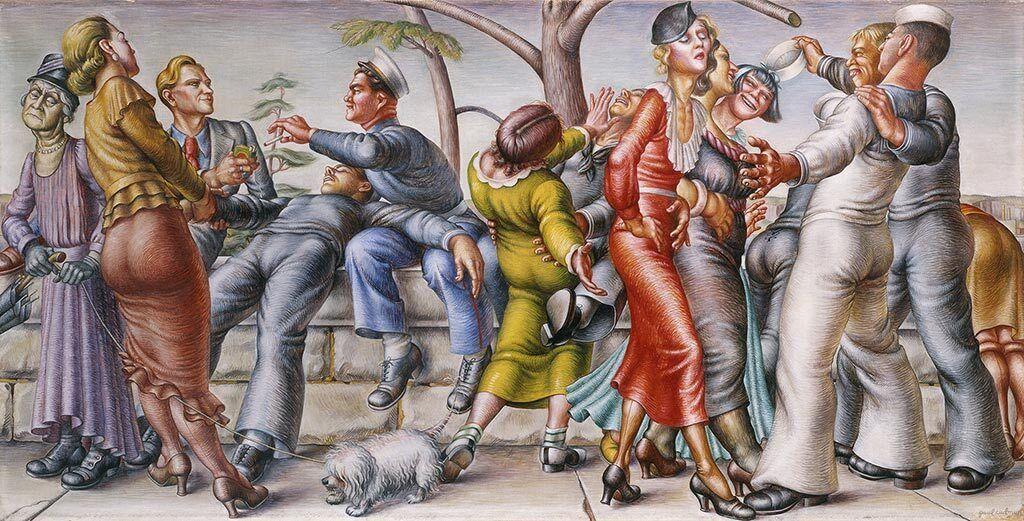

Paul Cadmus (American, 1904–1999). The Fleet’s In!, 1934. Tempera on canvas, 37 × 67 in. (94 × 170.2 cm). Courtesy of Navy Art Collection, Naval History and Heritage Command. Image © 2021 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Before I started to look into the 1950s, I realized it is important to understand a little bit about what was happening just a couple of decades earlier, in the 1930s. At this time, many Americans viewed sailors and seafaring people as part of the fringe of “polite” society and didn’t hold them to the same standards as the “respectable” folks who resided on land.

At the time, it was commonly believed that sailors who were on shore leave would partake in scandalous and debaucherous behavior, as depicted in Paul Cadmus’s controversial 1934 painting “The Fleet’s In!” (seen above). The artwork sparked outrage from Navy General Admiral Hugh Rodman who wrote, “It represents a most disgraceful, sordid, disreputable, drunken brawl..” showcasing a “number of enlisted men…consorting with a party of streetwalkers and denizens of the red-light district.” Although he was clearly offended, he wasn’t wrong. The painting even included some subtle and not-so-subtle queer-coded messages, such as two sailors in tight clothing with their arms around each other. Look closer and you will find a depiction of a man with “plucked eyebrows, rouged lips, powdered face, and marcelled, blonde hair” wearing a red tie––a queer signal of the time for being “available.” This man offers a cigarette to a Marine, who accepts it, another discreet encoded message within the artwork.

Paul Cadmus (American, 1904–1999). The Fleet’s In!, 1934. Tempera on canvas, 37 × 67 in. (94 × 170.2 cm). Courtesy of Navy Art Collection, Naval History and Heritage Command. Image © 2021 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

While this scene caused outrage from some, it might not have been an entirely inaccurate depiction of queer culture in the armed forces during the 1930s and 1940s. When the US entered World War II, millions of men and women were mobilized into service. Young people became part of a “massive wartime migration” that included 16 million men leaving home to become soldiers, while similar numbers of women left home to find wartime work. Suddenly, a generation of young men and women left the watchful eye of their hometowns and were exposed to new people and new cities, many of which had thriving underground gay scenes. In fact, serving in the military led many young people to meet others who were uncomfortable conforming to heteronormative roles or who rejected them entirely.

Historian Allan Bérubé (1946–2007) goes so far as to say that military service gave many recruits an opportunity to “begin a ‘coming-out’ process.” In the 1930s, “to come-out” or “to be brought out” meant someone had had their first homosexual experience. By the 1940s, gay men and women had adopted the phrase “coming out” to mean something more closely associated with the current interpretation of that phrase, meaning someone has found their “queer family” and/or they embrace a queer life, untethered to a first homosexual encounter. The process of “coming out” could be gradual and might involve queer signaling as well. In this period, someone “dropping hair pins” was a way to indicate they were “queer,” a word used by both the general public and gay people during World War II. When the time was right, someone could remove all their hairpins and “come out” by “letting one’s hair down,” a phrase originating within gay culture that had taken on a slightly different meaning in mainstream popular slang during this time.

The Lavender Scare

Despite many individuals being part of the 1930s and 1940s queer awakening, the majority of Americans were not ready to join a pride parade anytime soon. In the 1950s, the start of the Cold War created an alliance with anticommunist groups and the Christian right in America. The Christian right suggested that homosexuality was “a communist plot to undermine the moral fiber of the U.S.” and the federal government and FBI agreed. In 1953, President Eisenhower (1890–1969) ignited “The Lavender Scare” when he signed Executive Order 10450 that cited “sexual nonconformity as a basis for terminating or not hiring federal employees” and “prohibited gays and lesbians from getting security clearance and from working for the federal government.” This order remained intact until the 1990s.

During the Lavender Scare, every arm of the local and federal government was hostile towards the rights of queer people, and American society became fixated on the idea that communist could infiltrate the federal government. If someone did not conform to the public “norms,” they were subject to suspicion. Members of the LGBTQ+ community were viewed as security risks and could be subject to surveillance and intense scrutiny by the government. During the Lavender Scare, over 5,000 people were fired from government jobs due to suspicion of homosexuality. In addition, many queer people were arrested, imprisoned, and some were forced to undergo aggressive psychiatric treatment including castration, lobotomies, and electroshock therapy.

Homophile Groups of the 1950s

Some of the biggest tools to combat the Lavender Scare were protest, education, and organization––most notably in the form of two Homophile Groups that actively fought against Executive Order 10450. Originally formed in Los Angeles in 1950, the Mattachine Society began publishing The Mattachine Review and founded a branch in New York City in 1955. The mission was “educating the public in all aspects of homosexuality,” “effecting changes in social attitudes towards gays, and for securing the repeal of laws discriminating against gays in housing, employment and assembly.”

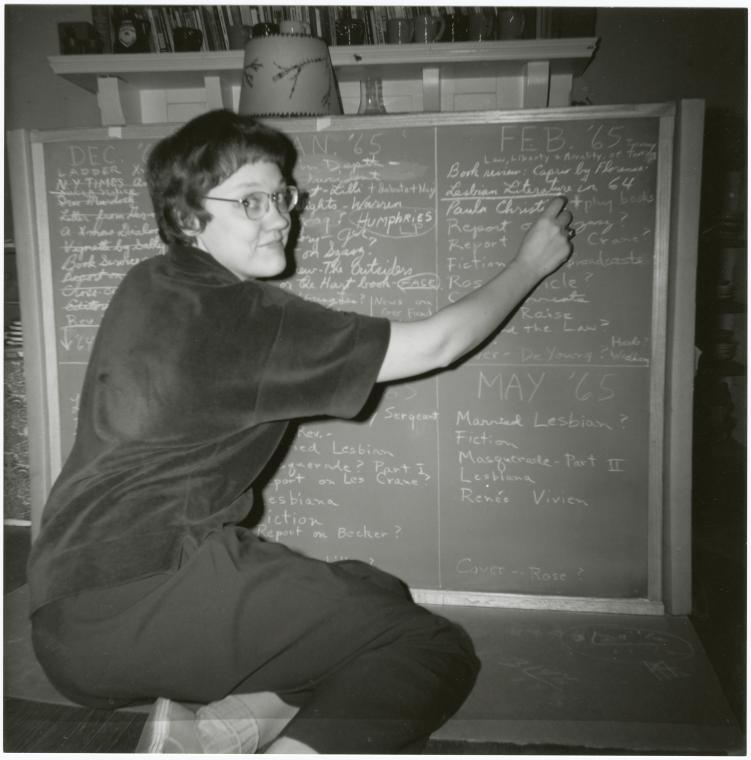

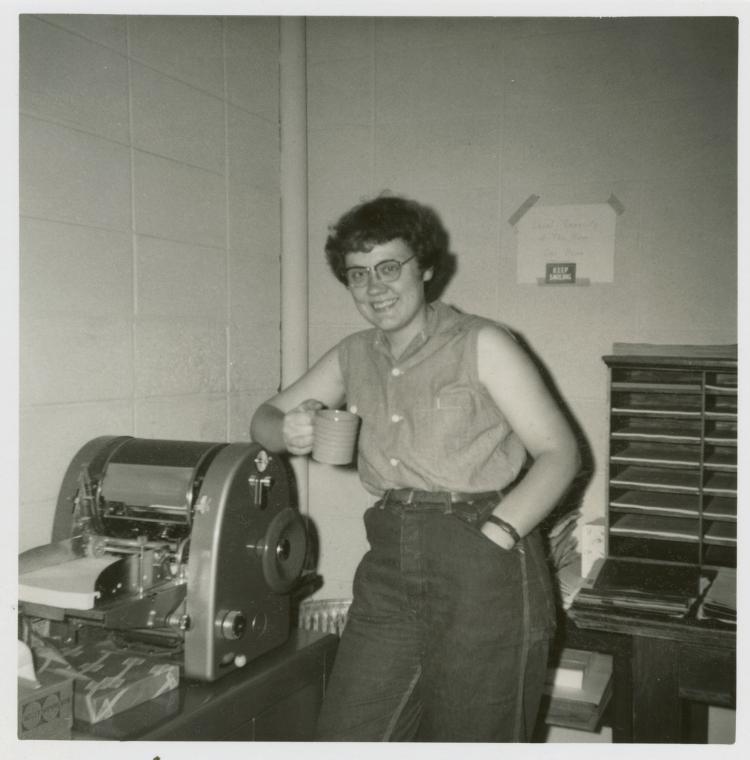

Left: “Barbara Gittings planning future issues of “The Ladder”” 1965. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Right: “Barbara Gittings, circa 1962, at the mimeograph machine, getting out the newsletter for the New York chapter of Daughters of Bilitis.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) was formed in San Francisco in 1955 without knowing that other homophile organizations existed. The DOB became the first lesbian rights group in the US and published the first nationally distributed lesbian periodical, The Ladder. The DOB opened chapters in cities across the country including New York City in 1958, which was founded by Barbara Gittings one of the earliest lesbian rights activists, and known as the “Mother of the Gay Rights Movement.”

Meanwhile at Sea…

It appears that at least some members of the Navy might have had views that aligned with those of members of the Mattachine Society and DOB. In 1957, the Navy compiled a nearly-700-page report known as the “Crittenden Report.” In this investigation submitted to Congress, it was found that homosexuals did NOT present any type of security risk: “many common misconceptions pertaining to homosexuality have become exaggerated and perpetuated over the years.”[1] A Long Way To Go. LGBTQ+ Seafarer, 1941-Present. The American Merchant Marine Museum, 2023. The document went on to recommend that gay and lesbian sailors no longer receive dishonorable discharges. Unfortunately, the Navy rejected all of the evidence in this report and even went as far as to bury its findings for decades by deeming its content “Secret” and continued to dishonorably discharge sailors and officers for being gay or even “associating with a known homosexual.”

Amidst all of this, LGBTQ+ sailors continued their lives at sea. The National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards (MSC) stood a beacon of solidarity, supporting racial equality and its many gay members. Unfortunately, the Coast Guard declared such activism as “security risks” and revoked many sailing privileges. The FBI went as far as to imprison the president of MSC and disbanded the union.

Harvey B. Milk enlistment record, 1951. National Archives, Identifier 145771929.

During this time, queer people continued to enlist in the Navy. Perhaps most notable was Harvey Milk (1930–1978), who would go on to inspire a new generation and serve as the first openly gay politician in California. Milk enlisted in the Navy Reserves in 1951, served mostly on rescue submarines, and was confronted three years into his service for his participation in a “homosexual act.” After being questioned, he admitted to this and several other “liaisons” with men, and was forced out of service with an “Other Than Honorable” discharge with none of his entitled benefits. In 1955, Milk willingly resigned from the Navy in order to escape being court-martialed. Despite all of his tribulations, Milk would go on to speak pridefully about his time serving in the Navy.

Despite the fact that Milk was forced to leave the navy because of his sexual orientation, in 2021 the Navy honored the assassinated politician, activist, and serviceman by naming a ship in his honor. The United States Naval Ship Harvey Milk (T-AO 6) is the first US Navy vessel to be named after an openly gay person. Milk was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 for his activism.

At a recent event in March of 2024, Rear Adm. Richard Meyer, deputy commander, US Third Fleet, said the ship, emblazoned with the name Harvey Milk, would communicate the values of the nation and the Navy wherever she sails. “Her crew will carry her namesake’s legacy and represent his courage of conviction,” Meyer continued, “always fighting for right” and marking the occasion as an “opportunity to right the wrongs of the past and to remember those who served and sacrificed on our behalf.”

It’s always good to end with a bit of hope. While researching this period in history for a potential program as part of the Seaport Museum’s Queer History series, I felt sadness, guilt, and gratitude. I felt sad that many of these men and women never got to see the positive outcomes of their efforts; guilty that I will hopefully never have to know the type of persecution and prejudice faced by these brave men and women; and grateful for their courageous commitment to living their truth. Despite what others may believe, these efforts paved the way for the more tolerant world of today––notice I said more tolerant, not completely tolerant. The fight is far from over.

During the 1950s, “all of the legal, cultural, and political barriers to gay equality were at their highest,” but queer people survived. Understanding this history helps us better appreciate where we’ve been, just how far we have come, and how easily that could all go away. Now, more than ever, it is important to be aware that LGBTQ+ rights are in danger. Some say history repeats itself. I think that only happens if we don’t learn from the past and figure out how not to repeat its mistakes. We must all stay vigilant and continue to be inspired by those who came before us to live our most authentic lives and never stop fighting for equal rights of not just queer people, but all people.

The victories I discovered while doing this research might seem inconsequential, but they laid the groundwork for what was to come: Stonewall, the repeal of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, marriage equality, the open representation of queer people in the media, etc. Their efforts really were like a ripple in calm waters that eventually led to a massive wave of change. I’m not sure if any of this will lead to a future program, but it has given me a new-found admiration for those queer trailblazers who came before me, gives me hope for the future and an even greater sense of Pride.

Have an idea for a future program in the Seaport Museum’s Queer History series? Reach out to [email protected].

Looking to learn more about diverse and underrepresented histories? Check out all the upcoming happenings on the Museum’s Programs and Events page! And, to be one of the first to know about new offerings, join the mailing list.

Highlights of the events in the Museum’s Queer History series, August 2022–May 2024

The first program presented was Queer History: 1990s and the New York Waterfront in August of 2022. When creating this program I sought out the advice of local historian, author, and curator, Hugh Ryan who wrote When Brooklyn Was Queer: A History. He was able to provide me with a great place to begin researching the recent history of queer culture in and around the waterfront of New York City and its boroughs in the 1990s. The 1990s might seem like an unusual place to begin a queer history series, but it was an obvious choice to me due to the Museum’s newly formed partnership with the Knickerbocker Sailing Association (KSA). KSA was founded in the 1990s as a non-profit gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender boating club that welcomes members of all sailing and boating experience to get out on the water in the greater New York area in a fun, safe, and supportive environment. Using KSA as a catalyst to dissect the complexities and obstacles of queer culture in the 1990s led to a deeper understanding and appreciation of the rights enjoyed by queer people today.

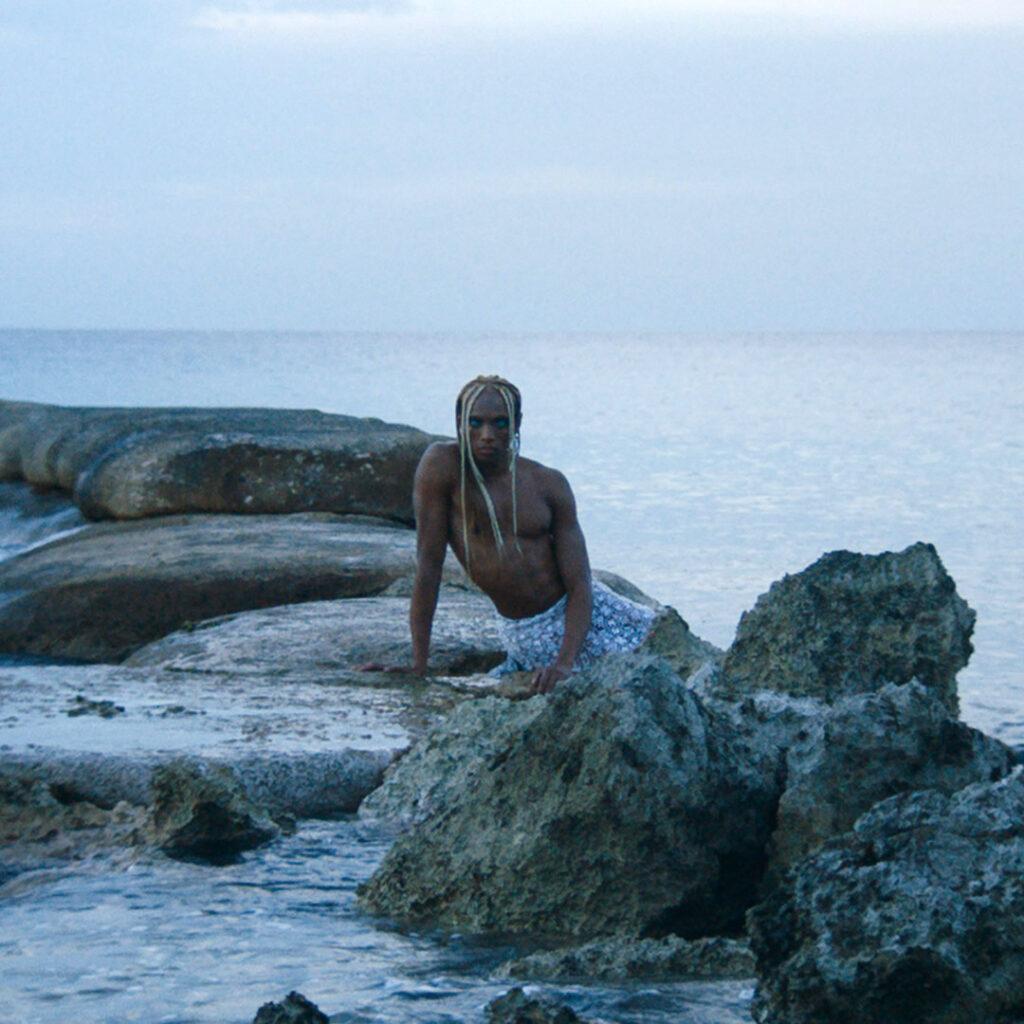

The success of this program encouraged the Museum to continue our exploration of contemporary queer history with Queer History: Gay Liberation and “Queer Occultism,” a candlelit historical exploration of how occult markets—of shops, fortune tellers, and psychics often considered deviant by law enforcement and society at large—emerged during the 1960s and 1970s, which allowed for the growth of informal and underground labor. This was followed by Queer History: Drag and the Waterfront, led by drag her-storian Linda Simpson, who delved into drag culture in and around the waterfront and lower Manhattan in the 1980s and beyond. Most recently, we presented the hugely successful Queer History: Notes on a Siren, where we presented a screening of Justice Jamal Jones’s film essay, Notes on a Siren, which intertwines Black and African spirituality, depicting how the siren becomes a vessel to explore archetypes of modern Black Queerness and Transness, and culminated in a live drag inspired performance from the Siren, La Sirène.

Additional reading and resources

Mattachine Society, Inc. of New York Records 1951-1976, The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts, 2024.

Harvey Milk: Veteran by Jessie Kratz, 2023. National Archive, Pieces of History Blog.

The Rainbow After the Storm: Marriage Equality and Social Change in the US by Michael J Rosenfeld, 2022.

Gay History: US Navy (Crittenden) Report 1957 by Brian A. Smith, 2022.

Paul Cadmus and the Censorship of Queer Art by Bryan Martin, 2021. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Facial Hair Friday: Allen Ginsberg by Jessie Kratz, 2021. National Archive, Pieces of History Blog.

When Brooklyn Was Queer: A History by Hugh Ryan, 2020.

Four Flowering Plants That Have Been Decidedly Queered by Sarah Prager, 2020, JSTOR.

Queer histories in the Navy by Joe Stanley, 2016. Royal Museum of Greenwich.

A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski, 2011.

Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II, by Allan Bérubé, 2010.

The City and the Pillar by Gore Vidal, 1946.

References

| ↑1 | A Long Way To Go. LGBTQ+ Seafarer, 1941-Present. The American Merchant Marine Museum, 2023. |

|---|