Cataloging the artist’s impressions on New York

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Martina Caruso, Director of Collections and Exhibitions

and Rob Wilson, Art Director and Operations Manager at Bowne & Co.

August 29, 2024

A friend and colleague of the Seaport Museum, Robert Warner, former Shopkeeper and Master Printer at Bowne & Co., Stationers, passed away about a year ago. He had left Bowne & Co. in 2019 after designing and printing hundreds of projects for enamored clients, creating thousands of artworks, and welcoming hundreds of thousands of visitors to the Seaport Museum. His mark on the Museum, on New York City, and on the world was made with care, confidence, and warm reverence for the act of making—an act he found to be essential.

During his time as Master Printer, Warner amassed a large collection of artworks, collage materials, vintage papers, ephemera, and memorabilia. After the announcement of his retirement, a specialized group of Museum and Bowne staff members began discussing what to do with these materials. The team has included the two of us—Martina Caruso, Director of Collections and Exhibitions, and Rob Wilson, Art Director and Operations Manager at Bowne & Co.—as well as Christine Picone, former designer at Bowne & Co., and Michelle Kennedy, former Manager of Collections and Archives.

In exploring Robert Warner’s legacy, what it means to us as staff members and colleagues of Warner, to the Museum as a whole, and to future collecting and exhibition activities at the Museum, we agreed to put in place a preliminary inventory plan of the objects, including documentation of temporary custody and transfer of ownership.

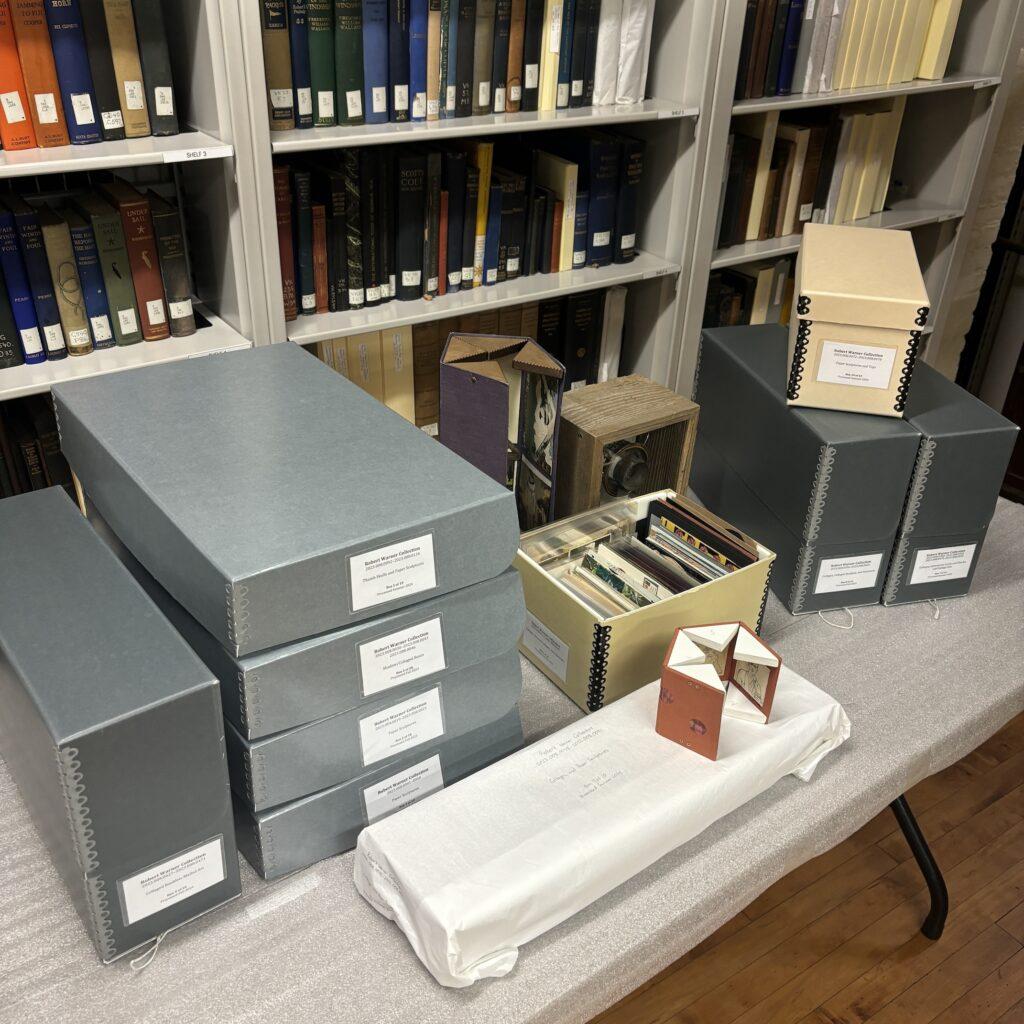

It took a few years to resolve the conversation, in part due to the Covid-19 pandemic and Warner’s failing health. Then in 2023, the Seaport Museum formally accessioned 495 works on paper by Robert Warner as part of the Museum’s permanent collection, chosen for their connections to the Museum’s printing and graphic art collection, to the Museum’s historical memory, and to the local art community. The pieces could also potentially function as a gateway for new programming on contemporary art creation.

Until this acquisition, the Museum did not previously own any pieces of contemporary mixed media art tied to the Seaport, with the exception of works of art by local artists Barbara Mensch and Naima Rauam. Warner’s works are examples of contemporary art made in the South Street Seaport Historic District with everyday objects, printing types, and printing equipment. In assembling these pieces of paper, fabric, and repurposed materials, he created a series of compositions that express the endless possibilities of letterpress-constructed narratives within the artistic community and society of the Seaport, and New York at large.

Research and Context

Robert Warner’s story starts in Geneva, New York, where a high school photography assignment sent him to an eyeglass grinding factory, taking black and white portraits of the workers. These workers would go on to be his colleagues, as he became enthralled with the world of eyewear. This passion took him to San Francisco, California, where he worked in a variety of boutique eyewear shops until returning to New York in the early 1980s as an optician for Morgenthal Frederics on Madison Avenue. In the 1980s, Madison Avenue was abuzz with some of the most famous people, and Warner’s presence was enormous. While at Morgenthal Frederics, he would fit glasses for Andy Warhol, Estée Lauder, Dudley Moore, Roy Cooper, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Alongside being an optician, Warner was a collector, with an unparalleled skill of finding the diamond in the rough. He was a local fixture at New York flea markets. His love of collecting led to the design of a Morgenthal Frederics bestseller, The Oberlin, a handsome round glasses frame with a keyhole bridge, with inspiration drawn from an early 1940s yearbook from Ohio that he found at a flea market. Warner collected in a way that could not be contained. He would fill all available space. As his Barrow Street apartment grew cramped, he began creating window displays for the Morganthal Frederics storefronts using vintage luggage and paper ephemera. He eventually was asked to design more and more window displays, so he expanded into a workspace on West 10th Street.

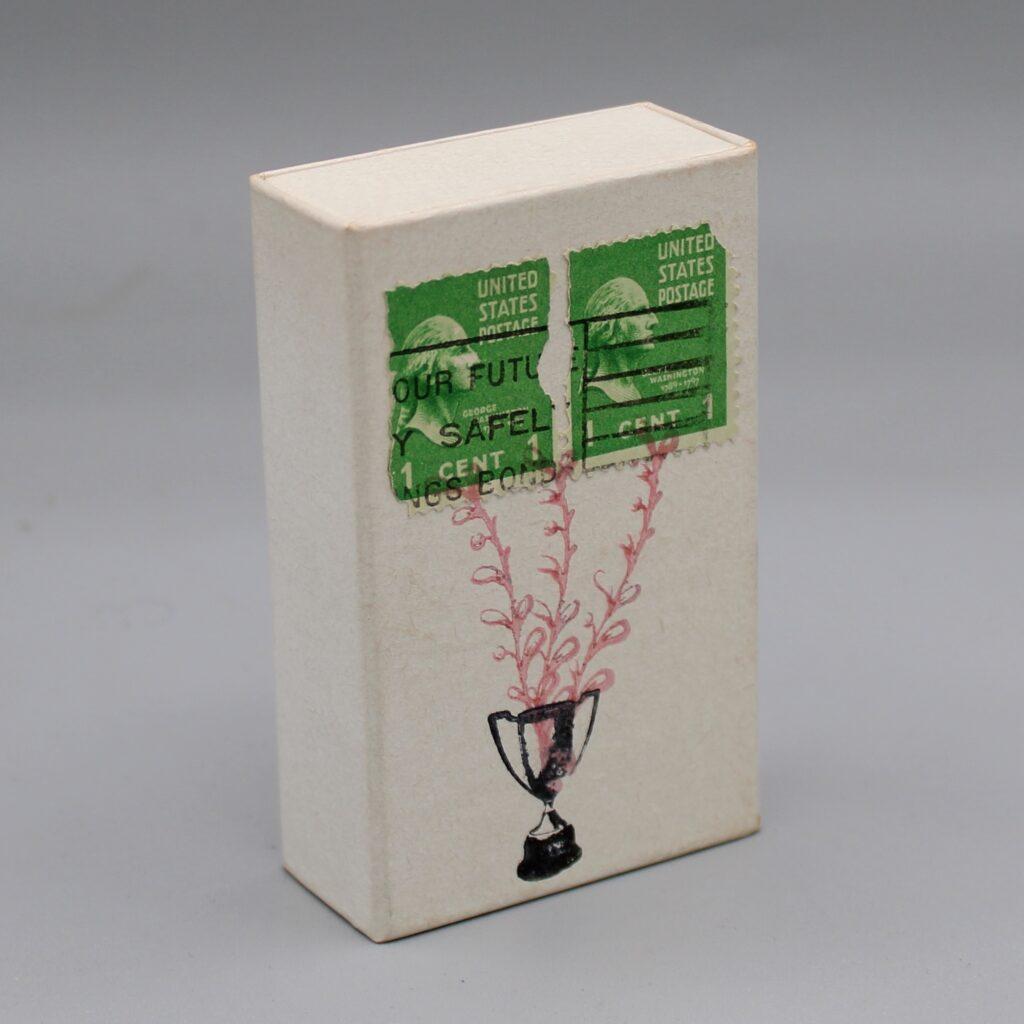

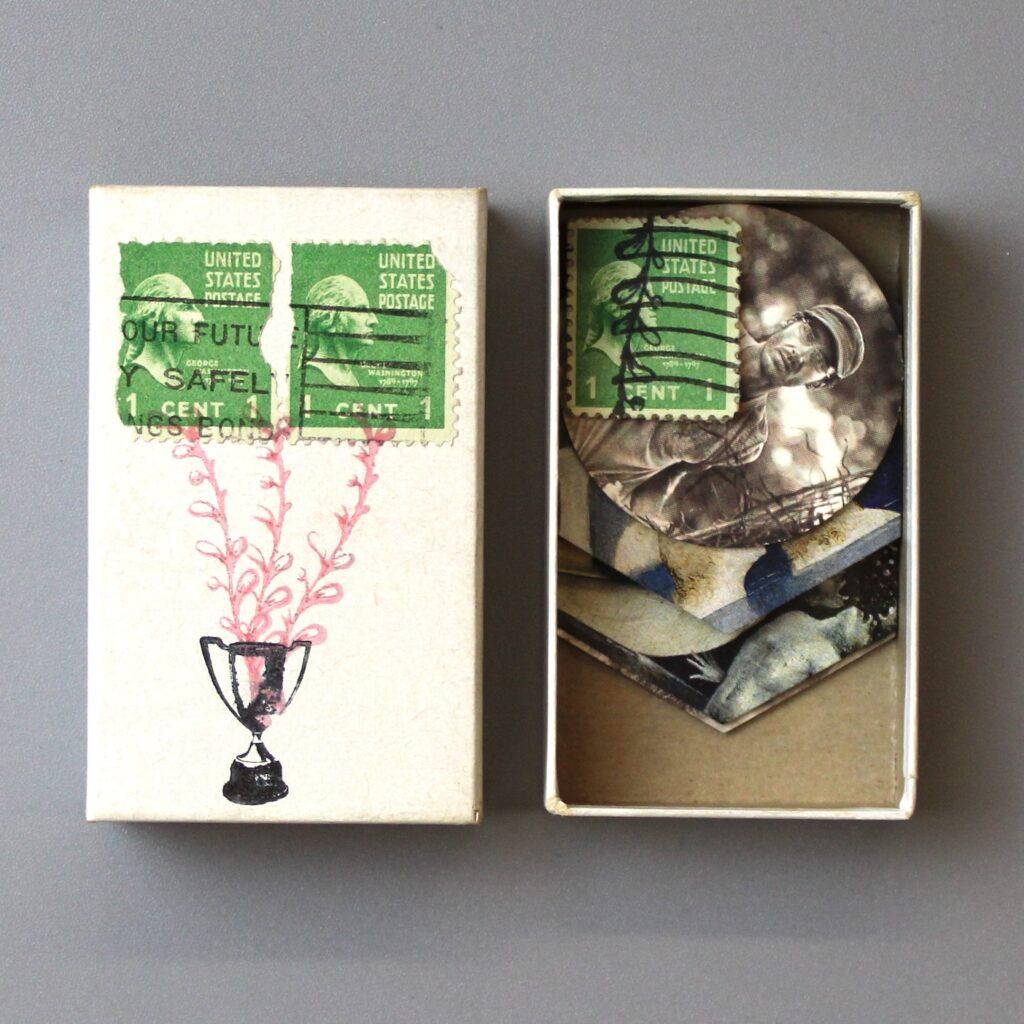

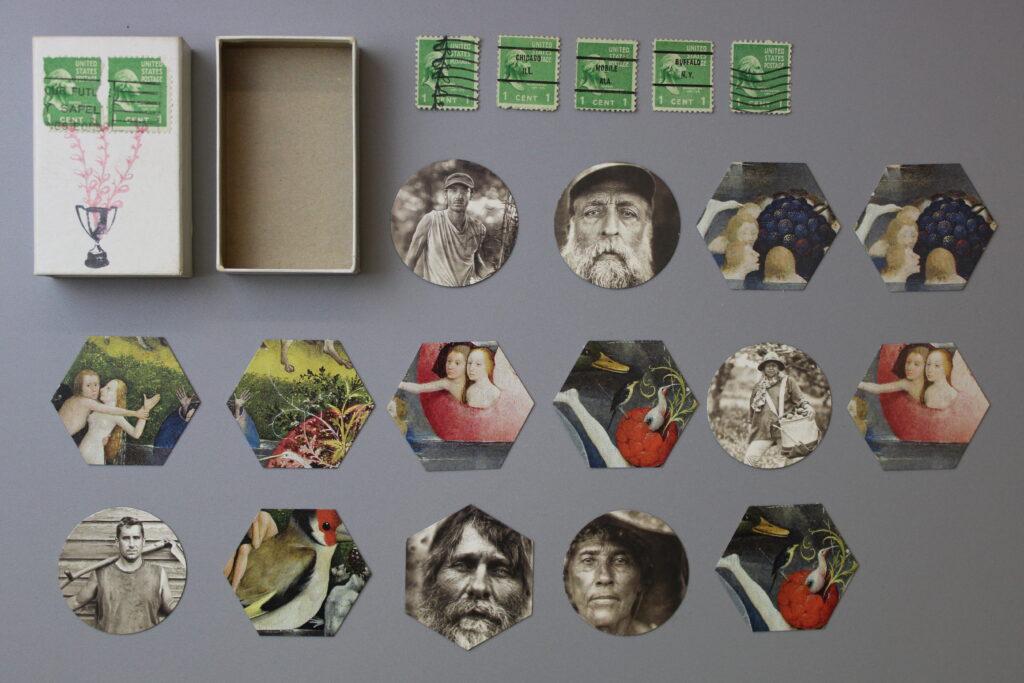

In 1988, Warner began corresponding with the American collagist and correspondence artist Ray Johnson (1927–1995). Their relationship was strong, even though they rarely met in person. They would send each other collages, interesting materials, found objects, and assemblages through the mail, and would frequently talk on the phone. Johnson looked to Warner as an art agent of sorts, sending him on missions to deliver messages to various galleries and run errands in the city, often buying artworks of Johnson’s that the artist felt were underpriced.

“Artist’s talk: Robert Warner” by Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive.

Over the course of their relationship, Warner received hundreds of pieces of mail art from Johnson, ranging from collages to a hand-delivered piece of driftwood. During one of their rare in-person meetings, Johnson gave Warner thirteen cardboard boxes tied with twine, labeled “Bob Box 1,” “Bob Box 2,” and so on. Warner continued making these boxes for the rest of his life[1]Learn more about it from an online conversation organized by the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive where Warner illuminates the intriguing contents of the “Bob Boxes,” gifts … Continue reading.

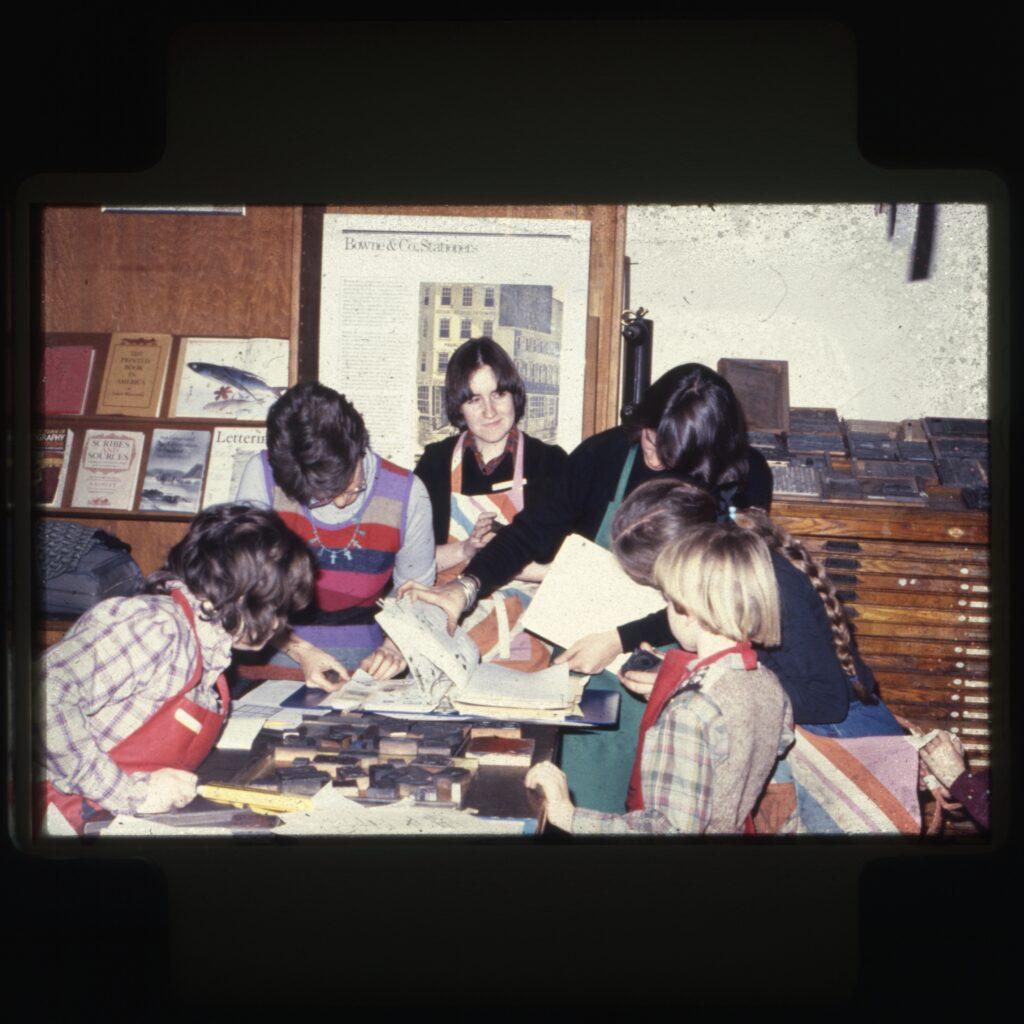

Johnson’s death in 1995 led Warner to his next chapter as a printer. Reflecting on his successful careers as an optician and a window display artist, he was looking for a new outlet and a new adventure. That same year, he walked into Bowne & Co., Stationers to buy recipe cards and was greeted by two printers working diligently in the back, but with empty shelves upfront. Warner volunteered to run the front of the shop as a shopkeeper, even after being told that he would not be taught how to print. Though Bowne & Co. Inc. had built a great reputation as a printer since partnering with the Seaport Museum to open a 19th-century-style print shop in 1975, it was under Warner’s care that the shop grew into a New York icon for those looking for something unique.

Bowne & Co. Stationers in 1975 and 1980. 35mm slides. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive.

In letterpress printing, the act of putting ink to paper is referred to as an impression. Robert Warner was a master at making an impression—with paper and with the people who came to know him. By the early 2000s, the printers at Bowne & Co. had taught Warner how to print and were no longer associated with the shop, but Warner remained. He developed a practice that is fairly unique in the letterpress printing world, often using the presses to make single impressions in service of future collages.

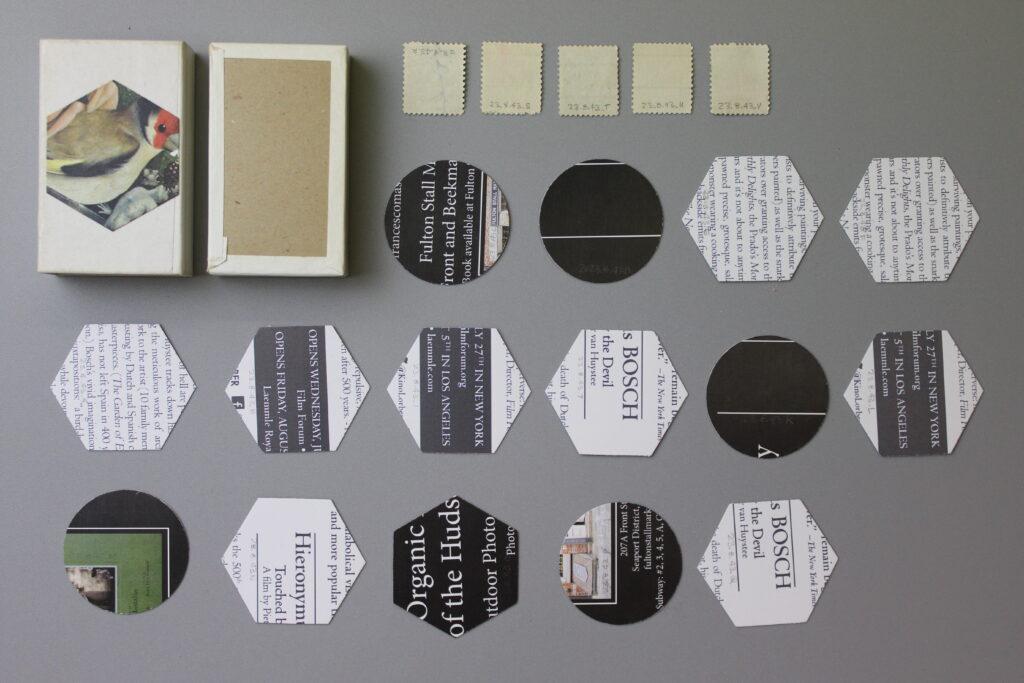

His practice looked effortless—often making 50 collages a day—but he was also methodical and iterative. The shop was filled with his presence, from the decor to the products for sale, and collections of materials that oscillated between retail products and artistic palette. A visit to Bowne & Co. was a visit into the mind of Robert Warner, as an artist, as a collector, as a collaborator, and as a friend.

Bowne & Co. Stationers, 2022. Photo credit Richard Bowditch.

He worked directly in front of the public and would sell, give away, or even make pieces in collaboration with visitors. New York (and further afield) is surely scattered with works he gave or sold for practically nothing to ordinary people.

Despite his connections with prominent figures in the art world, his attitude toward art and art-making was un-precious and unpretentious. He was constantly recycling old pieces to make new ones and abandoning works that no longer interested him. He would make things everywhere he went and would use anything he could find. He carried scissors and canceled postage stamps in his pockets like some people carry chapstick today. Those who had a chance to work with him often think about how, for Warner, letterpress printing and printed materials were simply means to an end of making.

Cataloging and Imaging

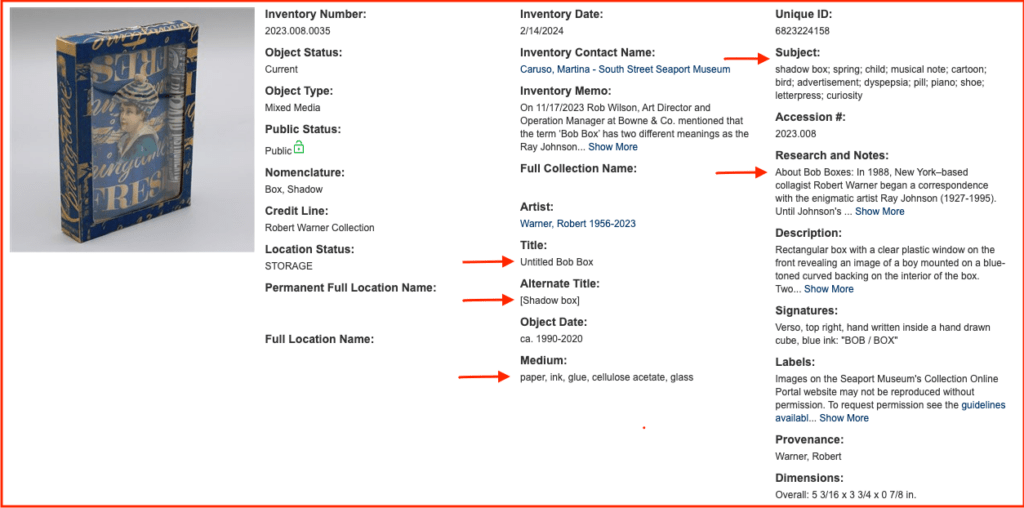

Robert Warner’s works have been cataloged using museum-standard Nomenclature[2]Robert G. Chenhall’s Nomenclature for classifying man-made objects is the standard cataloging tool for thousands of museums and historical organizations across the United States and Canada. … Continue reading and Getty Institute’s Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA).[3]CDWA is a set of guidelines for the description of art, architecture, and other cultural works. CDWA represents common practice and advises best practice for cataloging, based on surveys and … Continue reading However, due to the particular components and elements of the artifacts that are part of this acquisition, additional guidelines have been developed and implemented by the cataloging team who worked on it over time, including both staff members and interns.

First, the pieces were organized and arranged by type and series and re-housed in boxes of different types and sizes for their long-term care. Then, one by one, they were numbered and added to the collections management database system.

Then we approached their cataloging following three key principles. First, we had to decide the logical focus of each record. Should we concentrate on individual pieces? Or was it better to work on a series or grouping? How about multiples and components? While numbering the pieces, we were struck by the uniqueness of each piece, no matter which series and multiple they fell into, so we decided to concentrate on single items, and to catalog them for their individuality and peculiarity.

The second principle was consistency. We were pretty keen on creating a set of basic rules that could lead any staff or intern processing the pieces to be consistent in all aspects of entering information in the database, and establishing relationships between them. Titles, mediums, subjects, additional research, and notes are all fundamental fields that allow anyone to tell the story of each untitled paper sculpture, collage, and letterpress works of art, and their relationship to each other and to the Museum’s collections as a whole.

The third principle, which goes hand-in-hand with consistency, was specificity. We established rules for the degree of precision—or granularity—that one should use to catalog these pieces, and the degree of depth and breadth that catalogers should employ. In this part of the cataloging process, our past expertise and direct experience working with Warner was critical to allow each cataloger to understand, feel comfortable with, and enhance their database entries. Basic guidelines included concepts like “do not guess,” using only authoritative sources and research, prioritizing broad and accurate is over specific but incorrect.

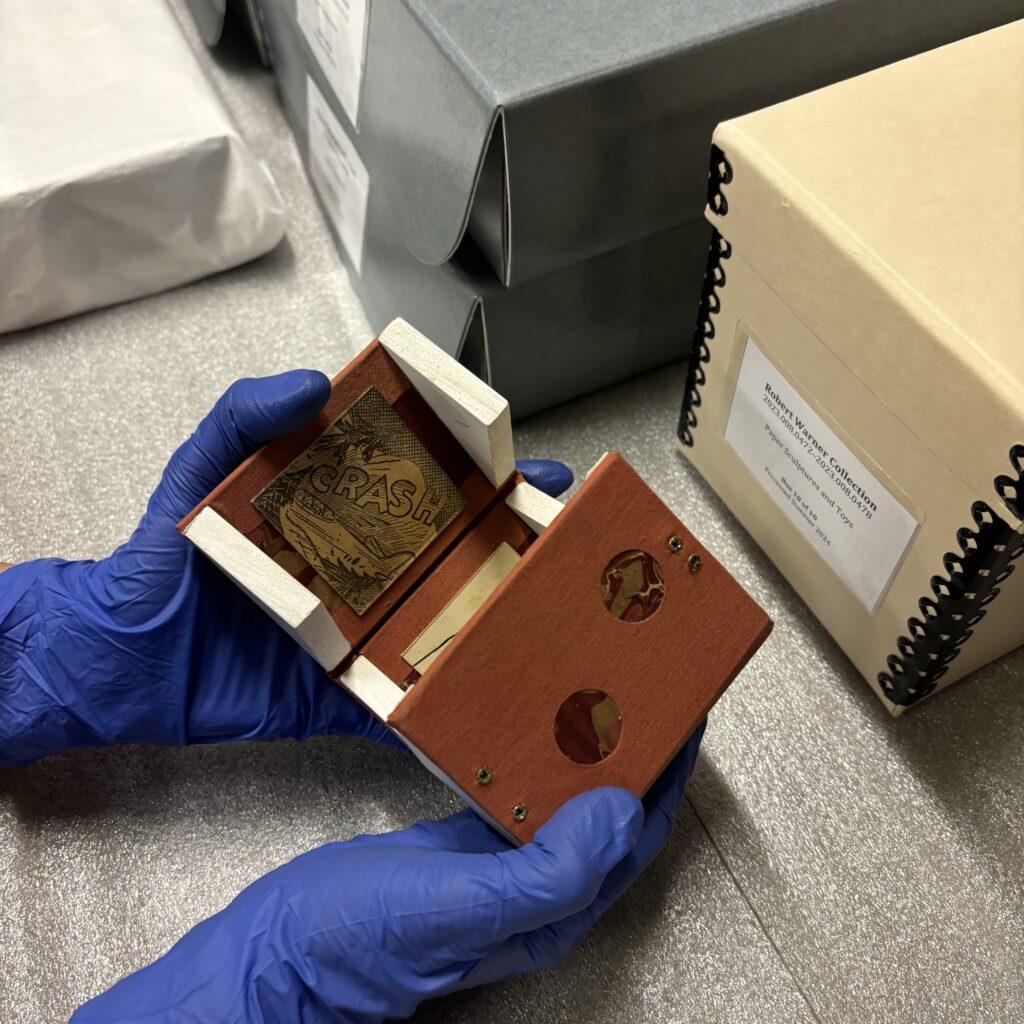

Imaging followed a similar logical mindset, as we wanted to be sure that we documented each side, folded pocket, standing easel, and additions that were not immediately visible. During this process, we often found additional treasures hidden inside the artifacts! Flat two-dimensional (2D) pieces were scanned front and back, while three-dimensional (3D) pieces were photographed to document each side and every hidden detail.

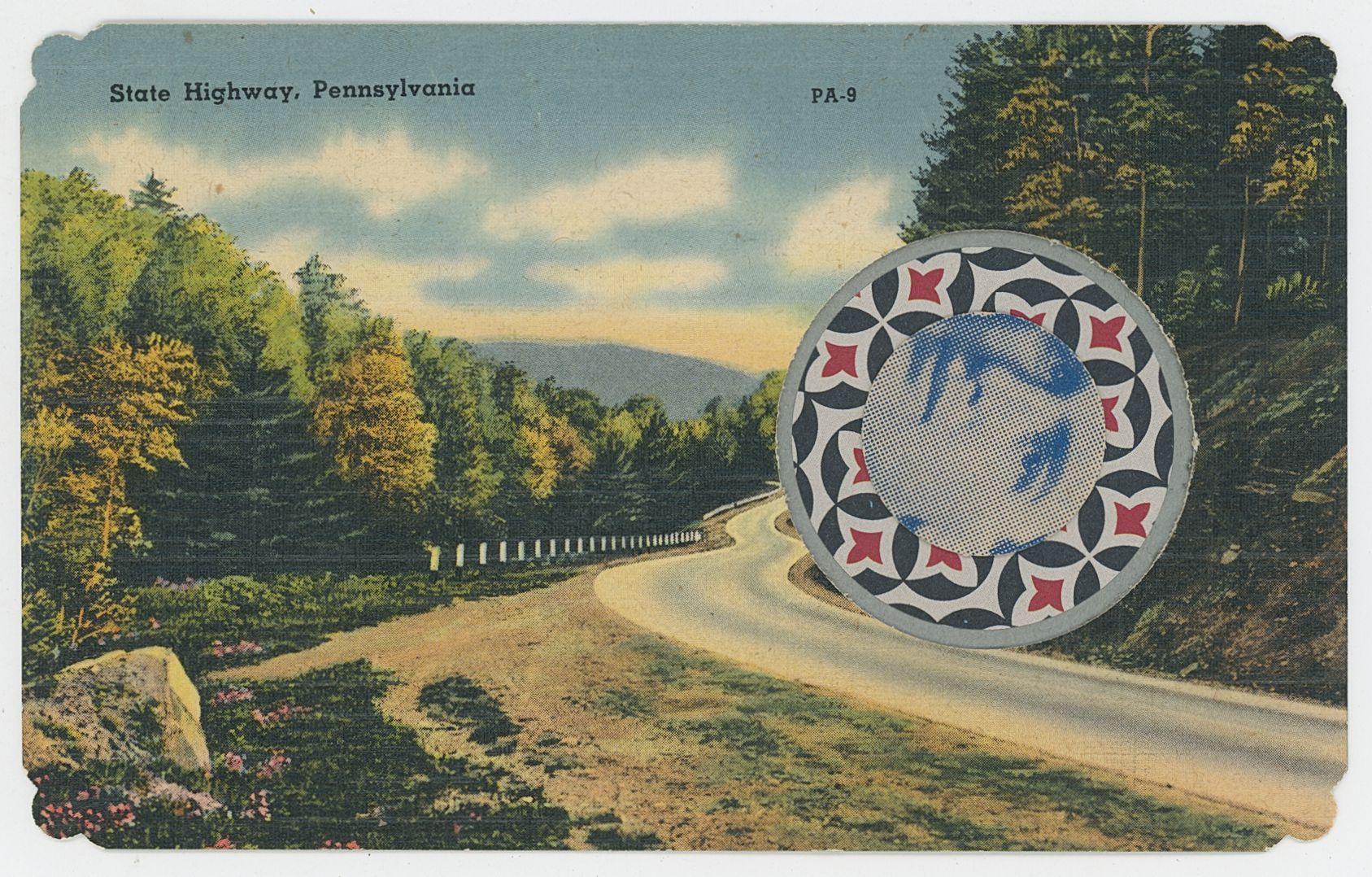

As of today, the Robert Warner Works on Paper Collection includes 300 pieces and encompasses a series of collages, paper sculptures, and letterpress ephemera representing Warner’s creative endeavors. His works on paper feature visual elements from the Museum’s typography collection, as well as vintage postcards, tintypes and cabinet cards, stamps, and many other found objects.

Here are a few favorites from the team who worked on cataloging and digitizing them this Summer.

Associate Registrar Carley Roche worked on over 100 objects over the past few months and noted, when asked to write about her favorite Robert Warner art piece, that two objects immediately came to mind. These pieces are complete opposites from one another: one is mainly 2D and appears simple, while the other is 3D and appears elaborate.

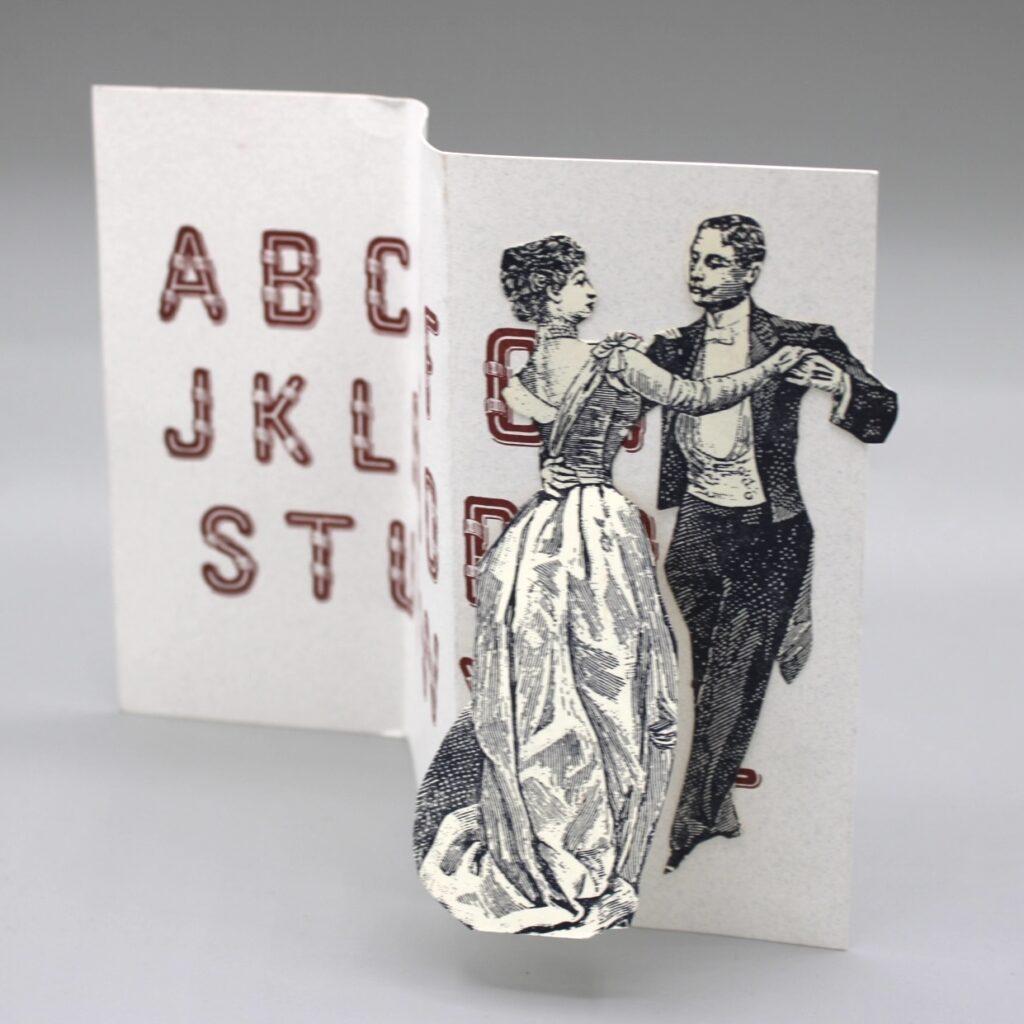

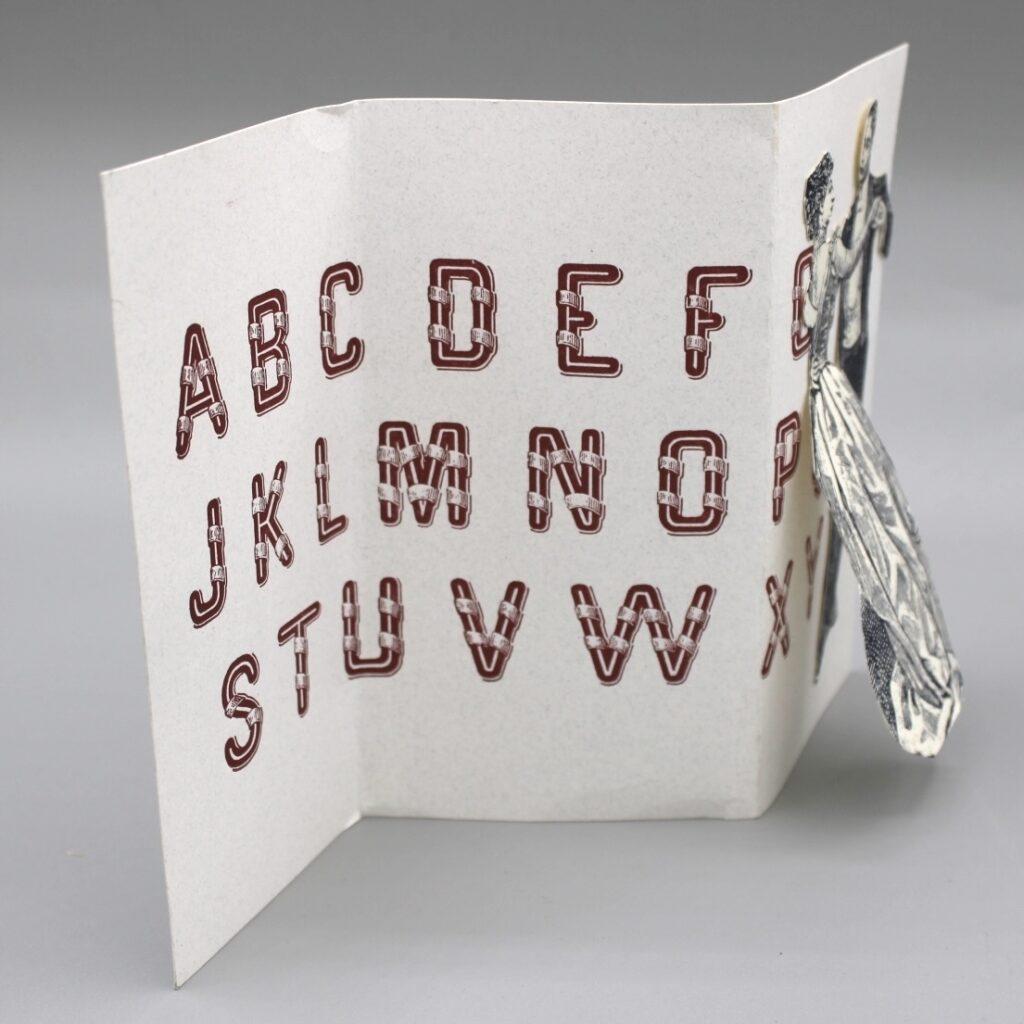

The first piece is an Untitled Paper Sculpture featuring a man and woman dancing together with the woman’s dress slightly popping up. The dancing couple is adhered to a white piece of paper with the Latin alphabet in red lettering. What draws Carley to this piece is that it appears simple but can be interpreted as complex.

For some people, dancing is as easy as breathing, while others have to work hard to learn the steps. For some people, the Latin alphabet is one of the first songs they learn as a child, while for others it is a second or third language. When the couple and the letters come together, it creates a beautiful work of art that highlights two very different ends of a spectrum.

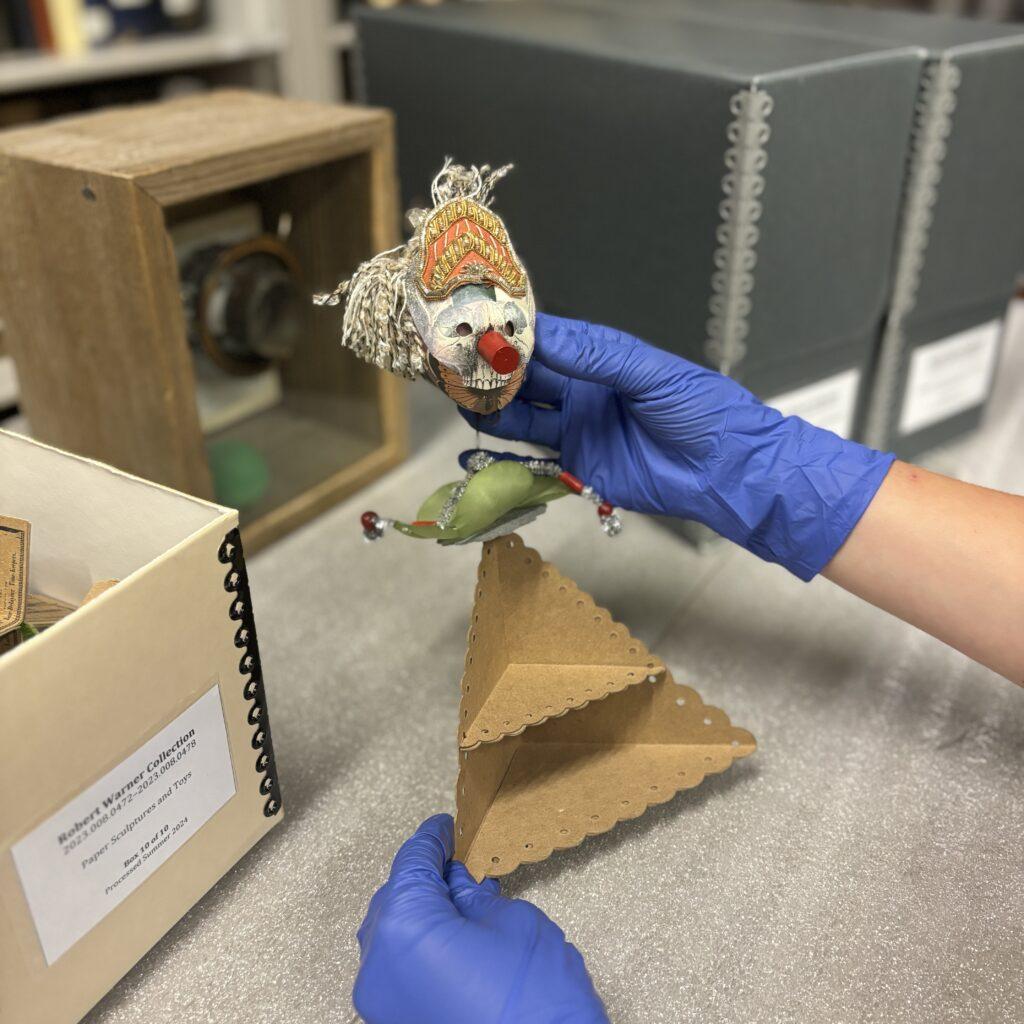

The second piece is another Untitled Paper Sculpture that appears to be a mixed media figurine. It is made from an array of different materials including cardboard, pipe cleaners, metal, plastic, wood, textile, paper, and ink—a real melting pot of mediums! But, when you step back and take in the object, it is a simple toy doll.

“Many young children can take any materials they find at home or outdoors and create wild imaginary scenarios and characters, and that’s what this object reminds me of. It is an amalgamation of diverse mediums that creates a simple character,” noted Carley. “Plus, I just really love the hair and crown.”

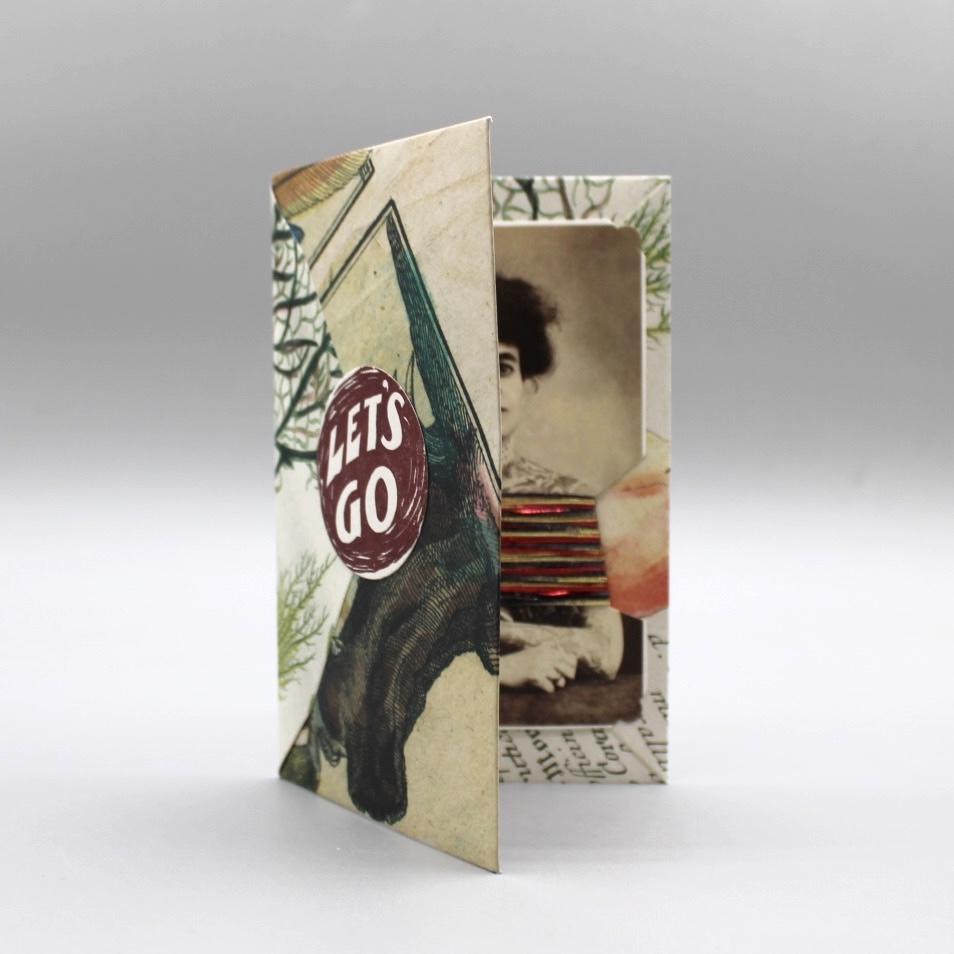

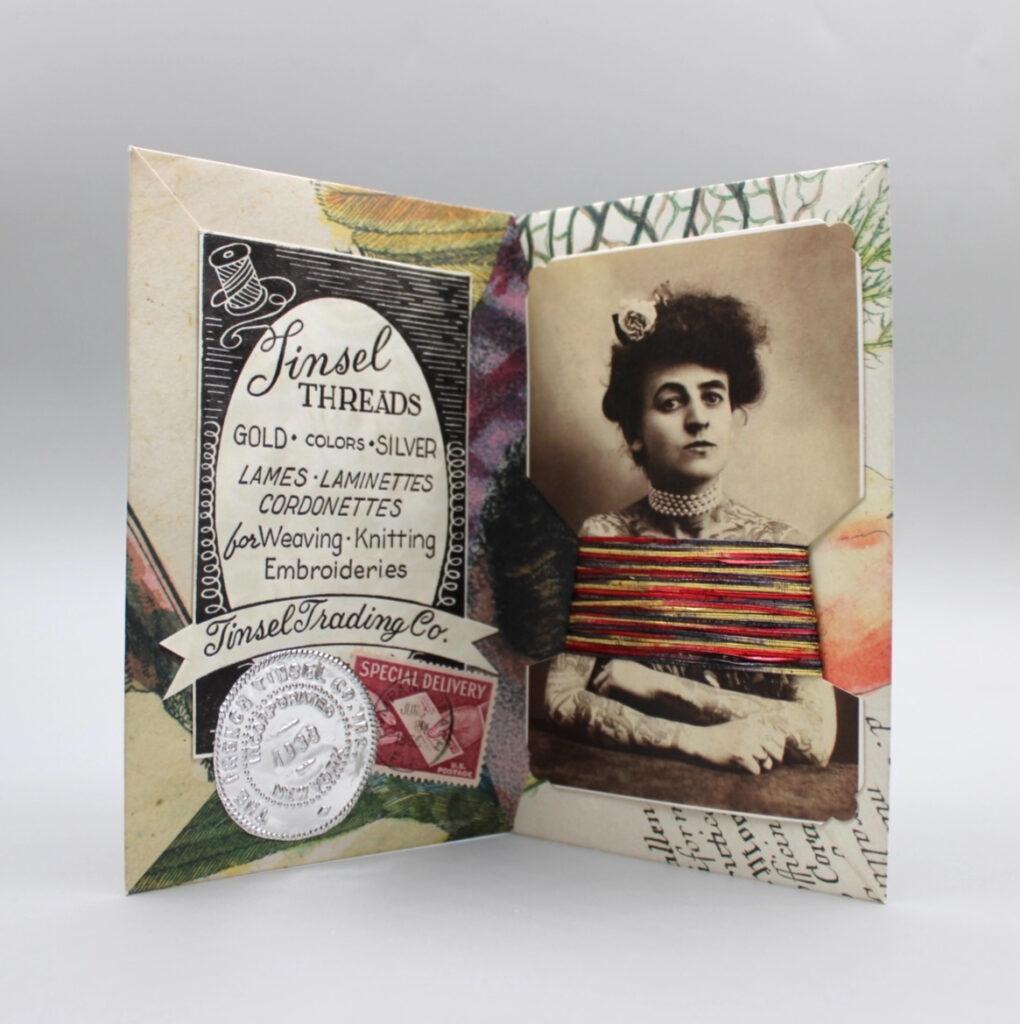

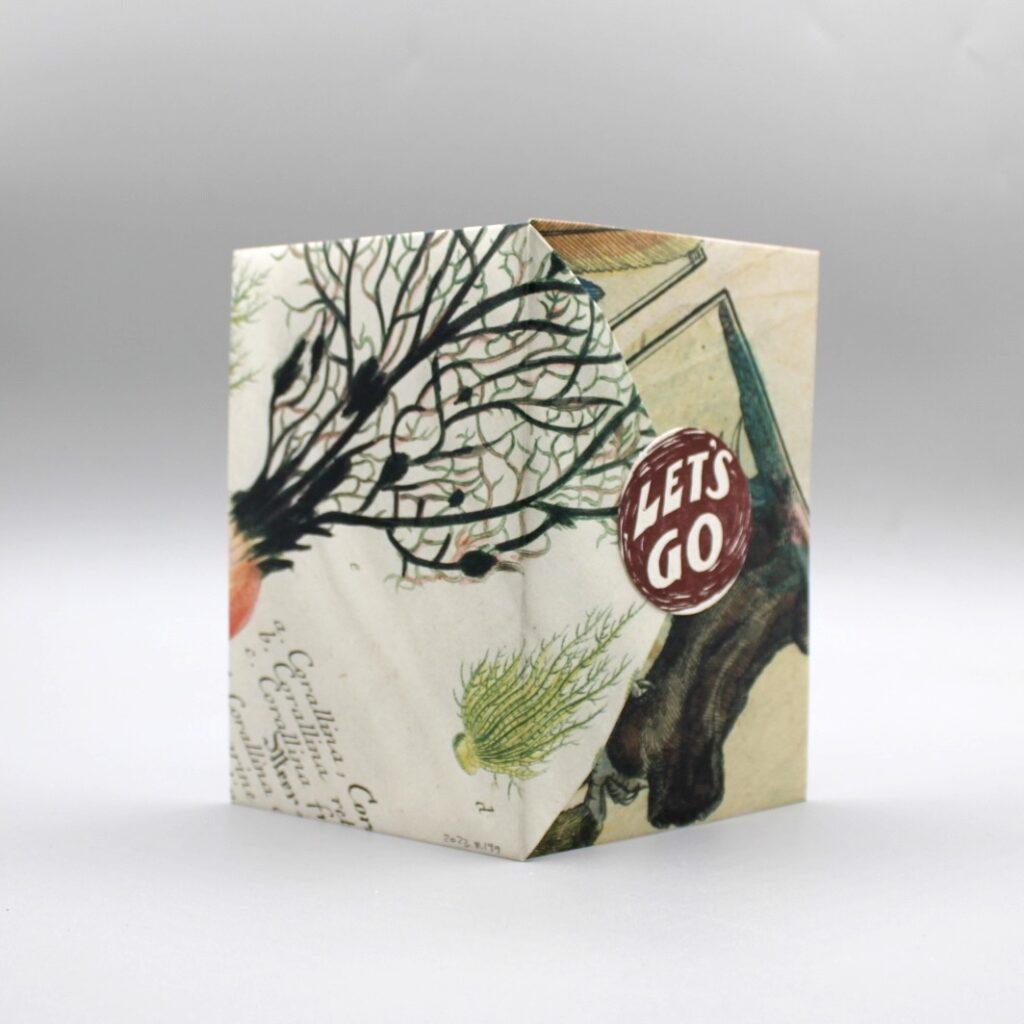

Collections and Exhibitions Management Intern Theo Schefer also spent the Summer processing Warner’s collection of collages and letterpress constructions, which took him back to “the innocent joy of arts and crafts time during elementary school.” Cataloging these pieces also brought out his inner history nerd, sending him down deep rabbit holes as he attempted to retrace the sources of found objects and iconography that gave Warner’s compositions life. “Through his art, it felt like I was uncovering another bit of New York, and even world history,” remarked Theo, and no piece satisfied Theo more than this Untitled Collage Notecard.

“I was initially perplexed by the distinct triangular folds and circular piece of paper affixed to the back until I realized what Warner modeled the piece after: a sealed envelope. Now excited to see what could possibly lie within the contents of the notecard, I opened it to see what was inside. There, I was greeted by a vivid assemblage of metal thread, letterpress items, business seals, and a single photograph. The photograph depicted Maud Stevens Wagner (1877–1961), one of the first female tattoo artists in the United States who worked alongside her husband Gus Wagner (1872–1941). After finding this connection to the Seaport Museum’s Alan Govenar and Kaleta Doolin Tattoo Collection, I had the opportunity to explore the origin of the Tinsel Trading Co. referenced on the left side of the card,” Theo went on.

“My research led me to a touching tribute to its founder Arch J. Bergoffen, made by his granddaughter Marcia Ceppos. Bergoffen was an army mechanic during World War I who went on to purchase the Manhattan-based French Tinsel Company in 1933. The business supplied metal thread to the US government in World War II and expanded the shop’s inventory to encompass the cords and other fabrics advertised in the notecard I was now looking at.”

Warner’s pieces do not just convey the joy of creation but a deep appreciation for the iconography that shapes the world around us, and this notecard demonstrates that beautifully.

The Robert Warner Works on Paper Collection is now available for everyone to browse for free on the Museum’s Collections Online Portal from anywhere in the world. Warner’s work has had a special ability to make connections, both old and new. His art will now live on in the Museum’s collections, where it can continue to build connections, reveal nuggets of history, and offer delight to the Museum community.

Additional readings and resources

Ray Johnson’s Collages, The Eighties and the Nineties. Ray Johnson Estate.

The Paper Sculpture Manual, Cincinnati Art Museum, 2022; based on The Paper Sculpture Show, a traveling exhibition curated by Mary Ceruti, Matt Freedman, and Sina Najafi in 2003 and produced by Independent Curators International (ICI), Cabinet, and SculptureCenter.

Forms of Address: Ray Johnson’s Bob Boxes, by Sarah Rose Sharp, Art in America, September 29, 2016.

Return to Sender: Ray Johnson, Robert Warner and the New York Correspondence School by Miriam Kienle, Guest Curator and doctoral candidate in Art History, Krannert Art Museum, 2013.

Artist’s Talk: Robert Warner, in conjunction with Tables of Content: Ray Johnson and Robert Warner Bob Box Archive / MATRIX 241 exhibition Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 2012.

Coaxing an Antique Press to ‘Kiss the Page’ by Ralph Blumenthal, The New York Times, January 4, 2010.

References

| ↑1 | Learn more about it from an online conversation organized by the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive where Warner illuminates the intriguing contents of the “Bob Boxes,” gifts to him from artist Ray Johnson. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Robert G. Chenhall’s Nomenclature for classifying man-made objects is the standard cataloging tool for thousands of museums and historical organizations across the United States and Canada. Nomenclature’s lexicon of object names, arranged hierarchically within functionally defined categories, has become a de facto standard within the community of history museums in North America |

| ↑3 | CDWA is a set of guidelines for the description of art, architecture, and other cultural works. CDWA represents common practice and advises best practice for cataloging, based on surveys and consensus building with the user community. |