Celebrating 10 years of Archtober: a look at some architecturally significant buildings in our district

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

October 1, 2020

If the 18th- and 19th-century buildings of the South Street Seaport Historic District exist today, it’s because of the South Street Seaport Museum. In the 1960s, New York City was undergoing one of its most dramatic reinventions, and the tension between urban renewal and historic preservation was center stage. After convincing the city to spare the buildings from the wrecking ball, the Museum’s founders—a group of passionate preservationists—set out to restore the area’s structures and repopulate South Street, “the Street of Ships,” with historic vessels.

The buildings of the district span a period of almost 200 years and they are representative of several different styles of mercantile architecture, including Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival, as well as the later Italianate and Romanesque Revival styles. Early stores and warehouses were designed by builders often unknown, while later 19th-century buildings were often the product of prominent New York City architects such as Stephen Decatur Hatch (1839–1894), George Browne Post (1837–1913), and Richard Morris Hunt (1827–1895).

Today, many of the original structures are a combination of several architectural styles as they were substantially modified at a later date. The Museum’s collections and archives document the stories of many of these buildings, their styles, businesses and occupants, their changes in use, as well as their restoration, or losses. Below are a few buildings that stood out to me, organized in chronological order of completion, while I was researching in the Museum’s maritime reference library files, and institutional archives.

Capt. Joseph Rose House (ca. 1773)

273 Water Street; unidentified Architect

This Georgian style house is the oldest building in the South Street Seaport Historic District and the third oldest in Manhattan (after the Morris-Jumel Mansion and St. Paul’s Chapel). It was built in 1773 before landfill widened the island, and the East River ran just behind the property.

The house is named after its commissioner, Captain Joseph Rose (date unknown), who was in the business of trading in sugar, mahogany, indigo, rice and tobacco in the Bay of Honduras. He shared a pier with his neighbor, merchant William Laight[1]According to the Encyclopedia of New York, William Laight and his son Henry were the first to maintain an extended record of New York weather, beginning in 1788. The New-York Historical Society has … Continue reading (date unknown), where they docked their two-masted square-rigged ships, or brigs.

Similar merchant class homes, with related wharves or piers, lined the streets of the neighborhood.

“Brig Industry and Captain Rose House”, late 20th century. Found in Collection, 1979.024.A-.B

In 1791 Joseph Rose and his family moved to Pearl Street, leaving the Water Street property to his son. After the beginning of the 19th century the street level of the Water Street house was converted to commercial use, and it’s recorded that in the late 1790s Capt. Rose’s son ran an apothecary there. In 1812 a cobbler shop was located on the ground floor, and before the Civil War the building was operated as a small hotel and saloon. In the 1860s, Christopher “Kit” Burns (1831–1870) purchased 273 Water Street, and opened a dance hall in the house called “Sportsmen’s Hall” where he offered a variety of distractions, including gambling, boxing, dancing, drinking, and the most renowned rat and dog fights as entertainment.

According to the district’s designation report[2] South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report, 1977, the original entranceway was likely located at the northernmost bay, where a single brownstone lintel remains, and the original pathway was at the southernmost bay of the building. The remaining original portions of the façade include the Flemish bond brickwork and two of the wood sills on the second story. A brownstone belt course divides the first from the second story. Splayed brownstone lintels distinguish the second story from the ones above.

Left: 273 Water Street. Photo from Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS NY-5681. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Center: 273 Water Street, February 2, 1976. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Right: Seaport Museum’s Walking Tour, September 2017

A fire in 1904 destroyed the original third story and peaked roof, and another fire in February of 1976 gutted the interior.

In 1997 the building was converted into a four-unit luxury apartment house. If you pass by you’ll often see tour groups standing in front of it, fascinated by the various lives, and illicit activities that occupied this almost 250-year-old structure.

Jasper Ward House (1807–1808)

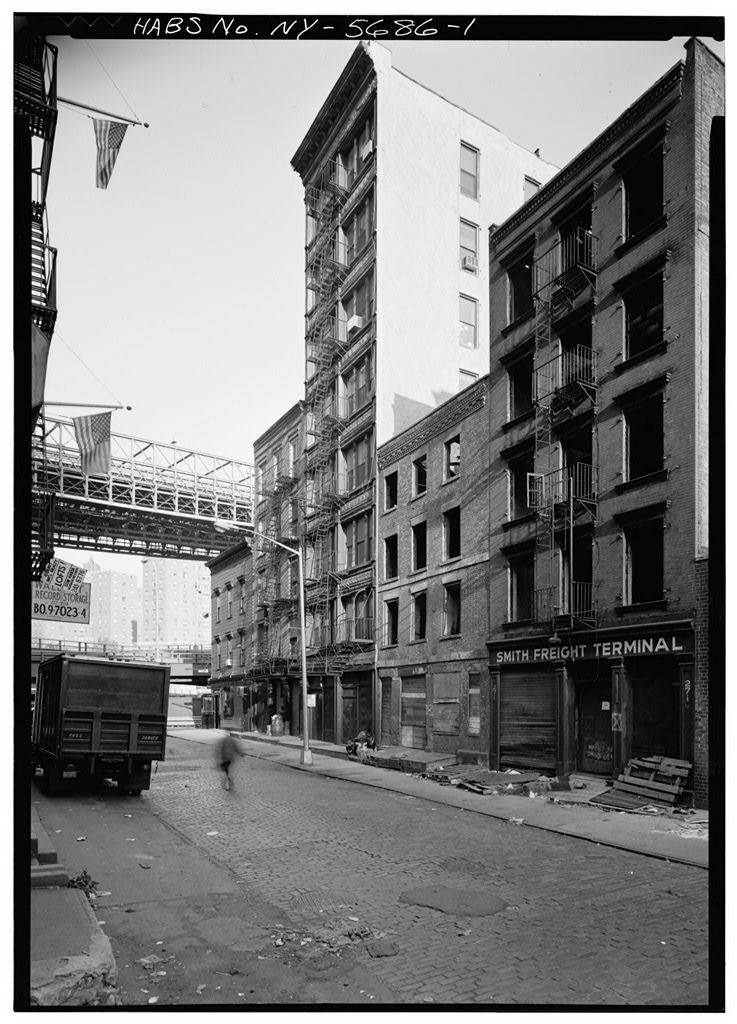

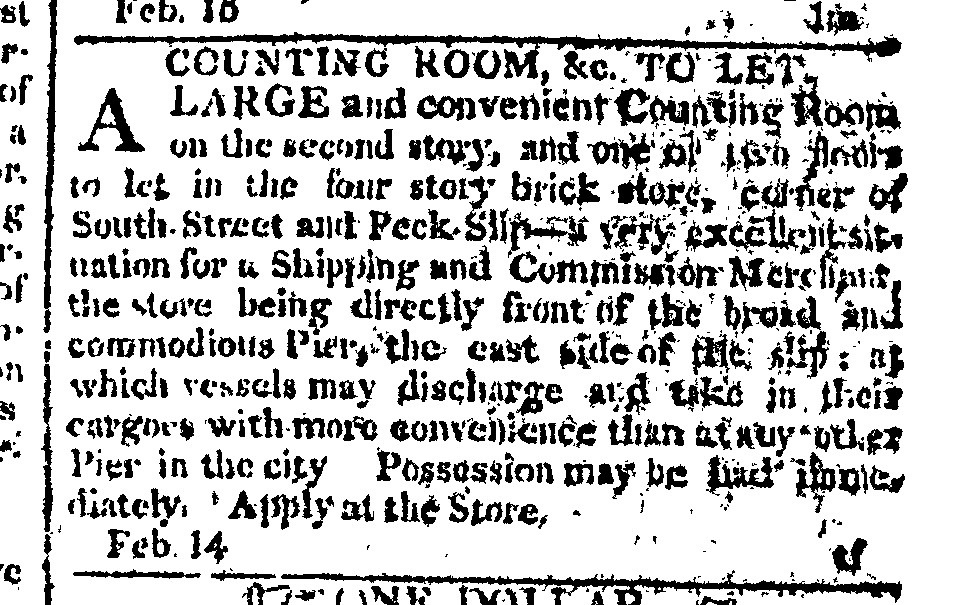

45 Peck Slip/151 South Street; unidentified Architect

This four-story brick building was part of a row of three similar structures erected in 1807–1808 by the merchant Jasper Ward (date unknown) at the corner of Peck Slip and what would become South Street. At the time that they were constructed Peck Slip consisted mostly of water lots[3]“A parcel of waterfront real estate that extended from the shore’s low watermark 400 feet out into the water, to be filled in by the owner at their own expense.” Unearthing Gotham, … Continue reading.

Each building had a heavy stone base with an expansive section of multi-paned windows above, for retail or office space. And above this, three floors of red brick with brownstone trim provided office space or rented rooms for seafaring sailors.

When the buildings were completed Mr. Ward advertised them in the New York Evening Post on February 21, 1807, describing the property as “a large and convenient counting-room on the second story, and one or two floors to let in the four-story brick store, corner of South Street and Peck Slip– a very excellent situation for a Shipping and Commission Merchant.”

The building changed hands throughout the 19th century, from import-export grocery businesses and wholesale grocers, to a ship chandler and a liquor dealer.

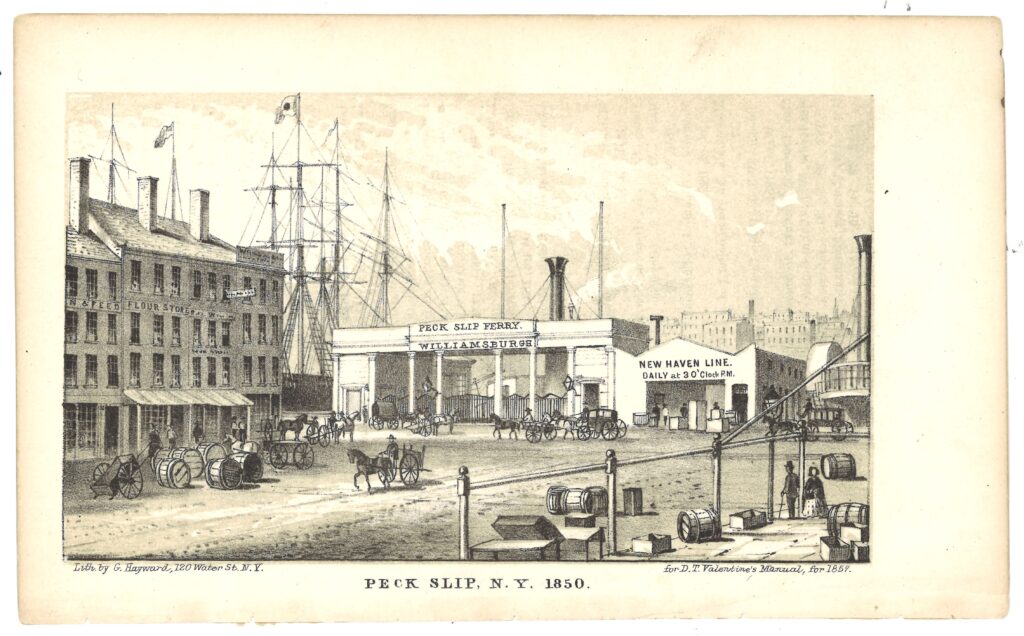

“Peck Slip, N.Y.,” 1850 by G. Hayward (ca. 1800–ca. 1872), for D.T. Valentine’s Manual, 1857. Gift of Rosemary McCann, 1995.002.0014

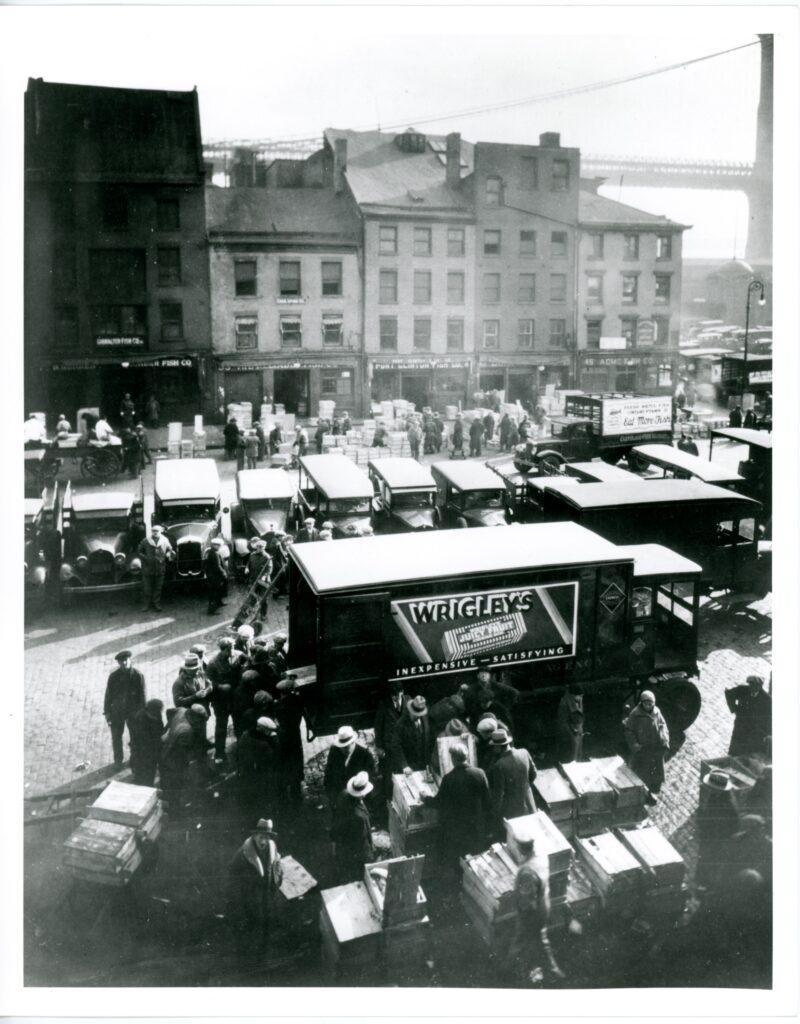

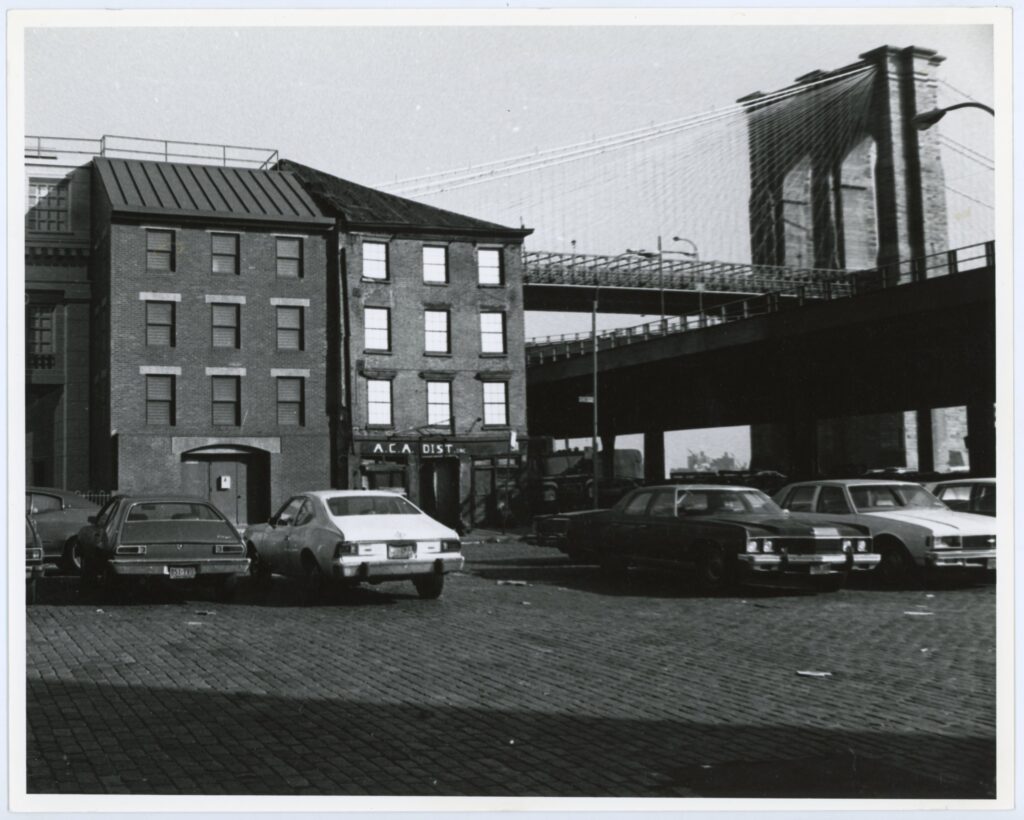

By the early 20th century the Seaport was the center of New York’s wholesale fish industry, and the building, like most of the other buildings in the neighborhood, was occupied by a business related to the Fulton Fish Market: Acme Fish Company. Acme left in the mid-1930s, and the buildings in the row at No. 41 and No. 43 were demolished in 1962. Peck Slip No. 45 was set to be demolished in 1973, but through cooperation between the Seaport Museum and Con Edison the structure was preserved.

Peck Slip, ca. 1925. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive H21-0072

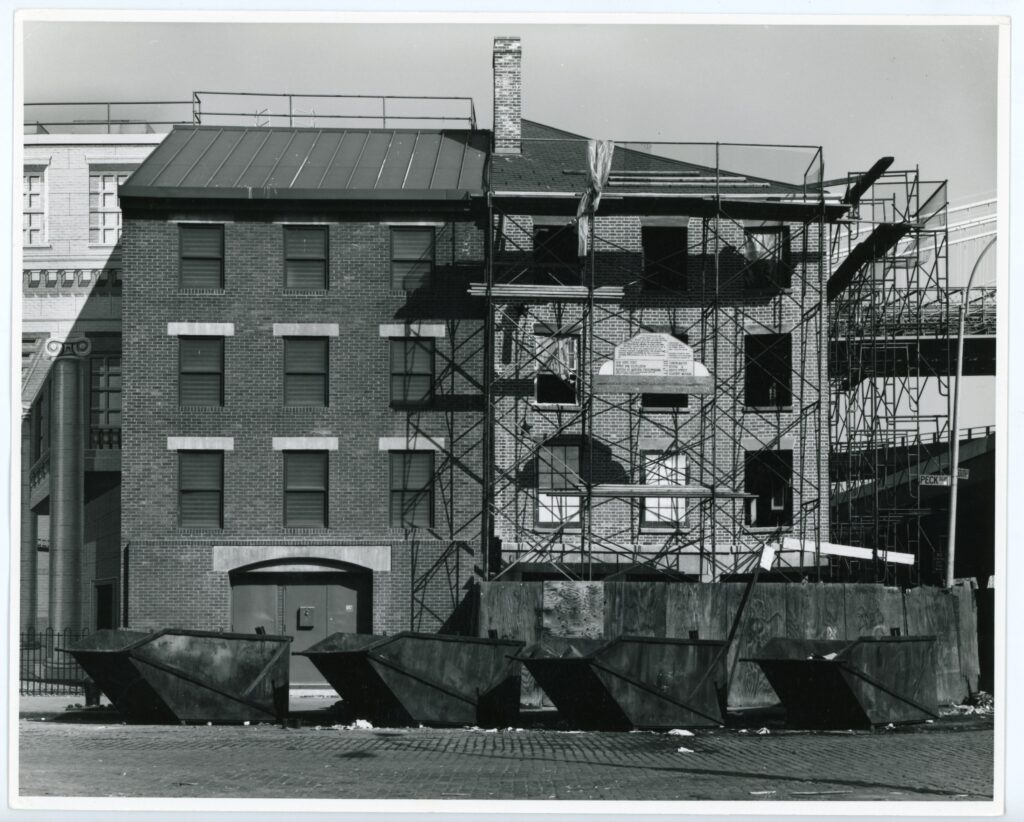

The building was officially donated to the Museum in 1977 together with funds towards its stabilization and restoration, in partnership with Columbia University’s School of Architecture, which planned to use the site as a training and hands-one classroom for its historic preservation program. Students took part in the research, drawing, historic documentation, and material analysis for the next few years as part of the newly established Center for Building Conservation (CBC).

Left: 45 Peck Slip-151 South Street, ca. 1978. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Center: 45 Peck Slip-151 South Street, ca. mid-1980. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

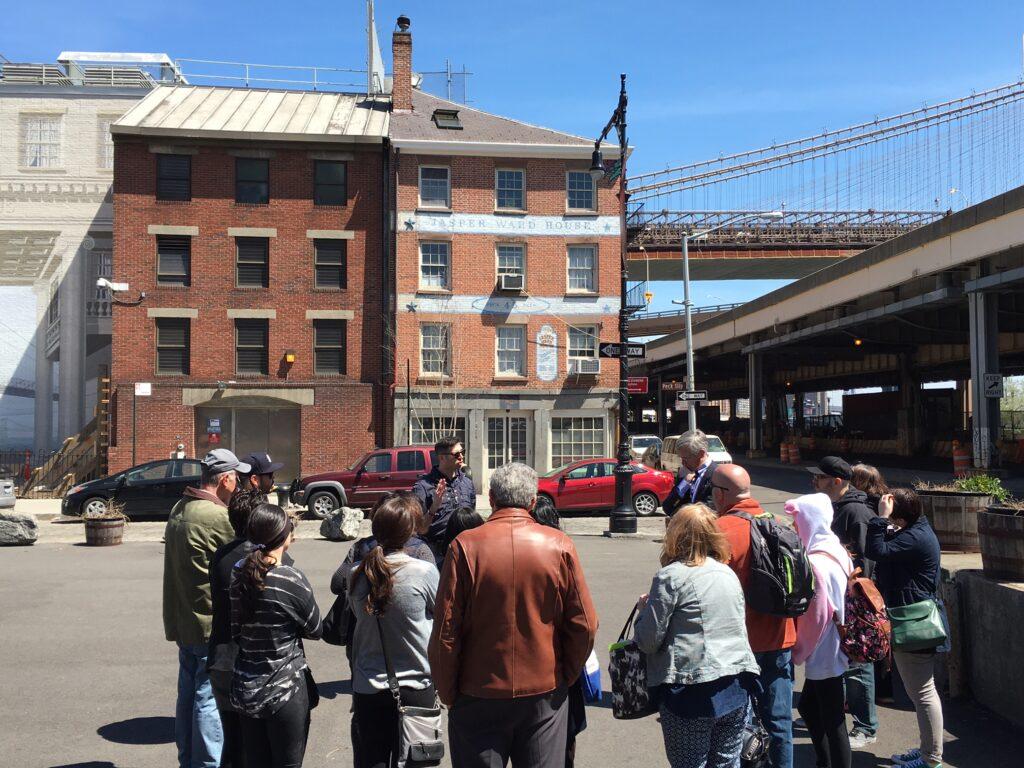

Left: Seaport Museum’s Walking Tour, 2016.

Unfortunately, the partnership ended in the 1980s, but today the building, which is no longer property of the Seaport Museum, retains its original Flemish bond brick facade and splayed brownstone window lintels and sills. Peck Slip is a large public space, and the ConEd power station is characterized by a large mural made by renown muralist Richard Haas (b. 1936) in 1978, entitled “Peck Slip Arcade.”[4]”The murals of artist Richard Haas are stunningly realistic. Since the 1970s, Haas has created hundreds of trompe-l’oeil murals in cities across the world, from Boston to Chicago, and Miami … Continue reading

Harriet Onderdonk Building, later known as Meyer’s Hotel (1873)

116-119 South Street; designed by John B. Snook (1815–1901)

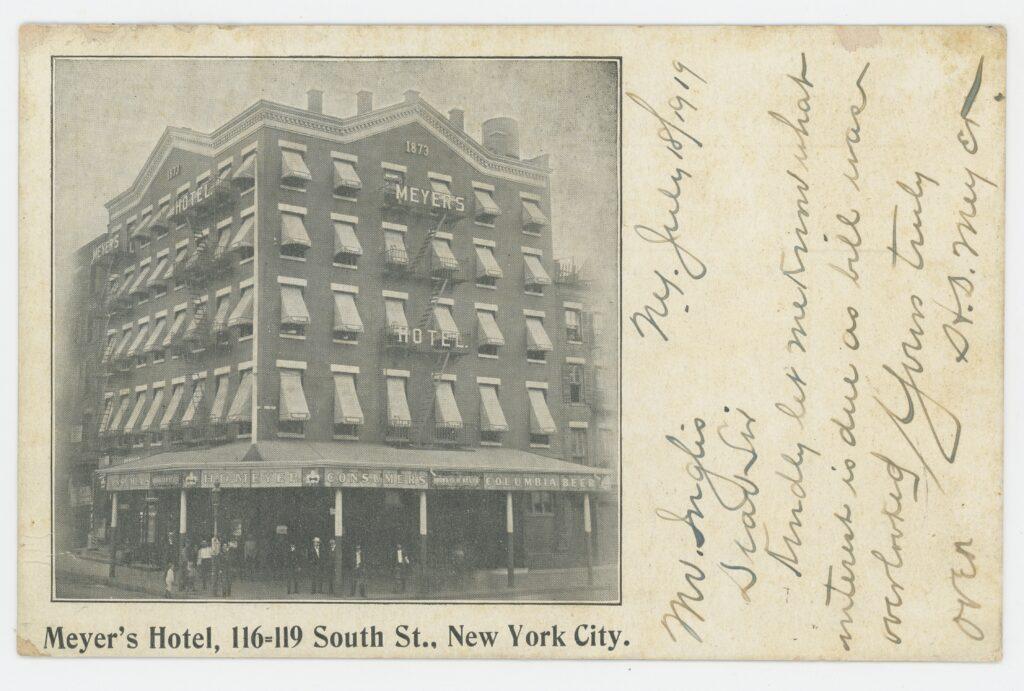

Built in 1873, this double brick building was designed by prominent New York City architect John B. Snook for Mrs. Harriett S. Onderdonk (1820–1904) and Mrs. Harriet L. Mann (1866–1932). The building was supposed to be a combination of stores and lofts, but was converted into a hotel just ten years later by liquor merchant Henry L. Meyer (date unknown).

Mr. Snook was one of the most renowned architects in New York in the late 19th century; among his many notable projects include the original Grand Central Depot on 42nd Street (1871) –the building that the present Grand Central Terminal replaced in 1913– as well as many buildings in the Soho Cast-Iron District[5]”The intricate facades of SoHo, once considered merely functional, have since become symbols of urban elegance, embodying a unique blend of industrial strength and artistic beauty. On … Continue reading

The building replaced two earlier structures at 44 Peck Slip and 117 South Street, and Snook elevations of both facades, floor plans, and transverse sections could be found at the New-York Historical Society, together with his account books, contract books, and ledgers, which detail the construction process.

Meyer’s Hotel Postcard, ca. 1915-1925. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

In 1903, Henry L. Meyer applied for a permit to change 117 South Street from “stores, offices and lofts” to “stores offices and boarding house.” Before the alterations, the building contained a bar/restaurant on the first floor and loft on the second floor. The third floor was vacant and the fourth and fifth floors served as lofts. After the alterations, there was a bar and restaurant on the first floor, offices on the second, and a total of forty-one hotel rooms on the upper three floors.

Frequented by Thomas Edison, there is a theory that Meyer’s was the first hotel and bar to have electric lighting. Famous guests reputed to have stayed at Meyer’s Hotel include Annie Oakley and “Buffalo Bill” Cody, as well as outlaws Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Teddy Roosevelt was known to drop in at the bar on occasion for a pint while serving as the head of the New York City Police Department, supposedly looking for officers who indulged themselves while on duty.

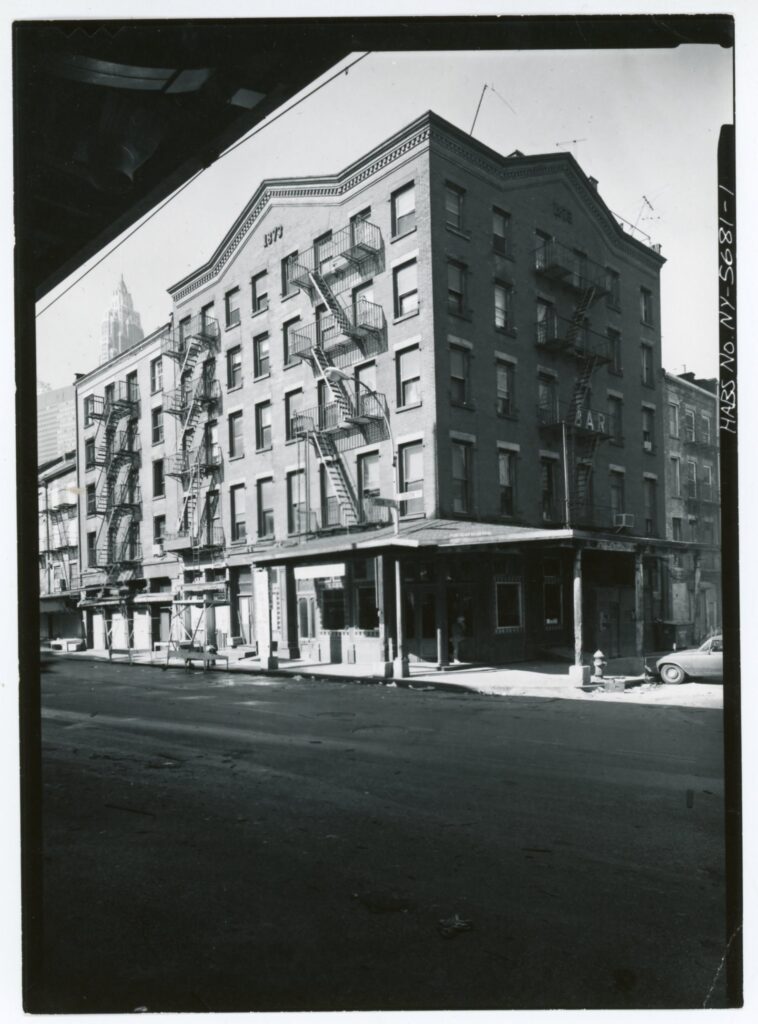

Left: Harriet Onderdonk Building, 116-119 South Street, ca. 1976. Photo from the Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS NY-5681-1 Retrieved from the Library of Congress

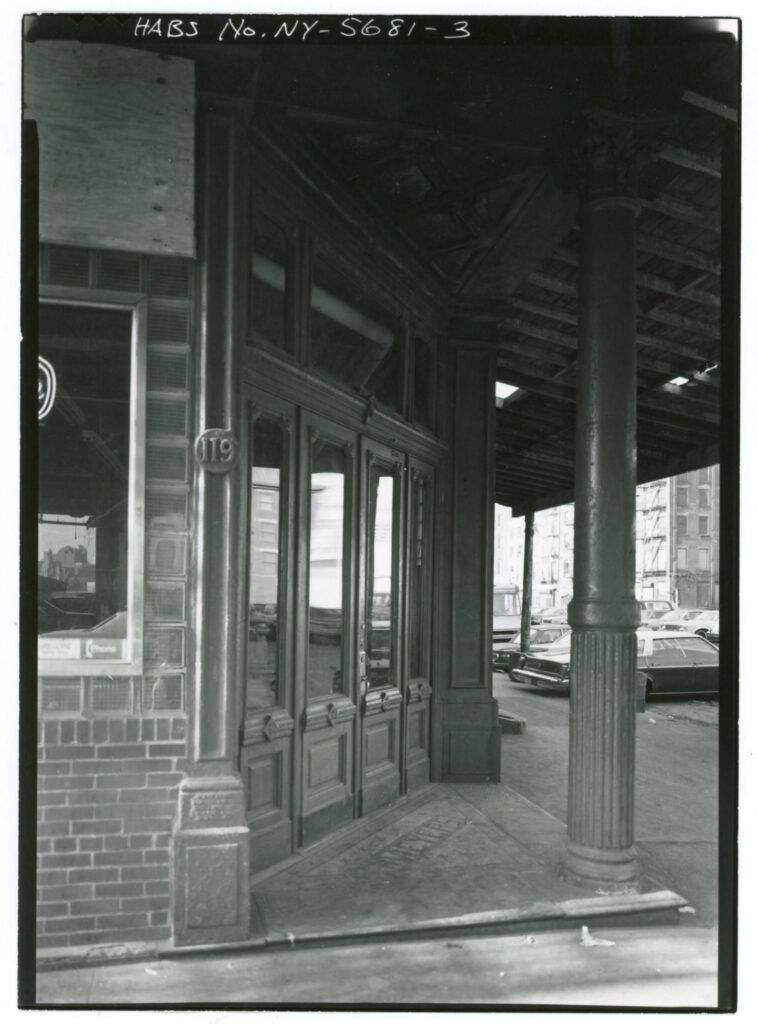

Right: Detail of Corner Entrance, Harriet Onderdonk Building, 116-119 South Street, ca. 1976. Photo from Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS No. NY-5681-3. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

The next major alteration took place in 1953 after South Front Realty Company purchased the building from Henrietta L. Meyer (1897–1954) in 1951. The number of small hotel rooms remained the same, 41, but many improvements were added including a second floor barber lockers, new toilets on the first, third, fourth, and fifth floors, exit fireproof windows, fire escapes, and a new sprinkler system.

It is unknown when the elaborate carved Victorian bar was installed on the first floor. Most probably, it is either original or dates from 1883, when Henry L. Meyer bought the building.

The hotel operated until the early 1980s, when it was possibly one of the last single-occupancy hotels left in the seaport district.

“Larry Lombardi and Ship Captain Ed Moran in the Old Paris Bar” ca. 1980 (original negative), 2008 (print) by Barbara Mensch (b. 1950). Museum Purchase 2008.005.0006

More recently the first ground of the old Meyer’s Hotel became the renowned Paris Café, and the upper floors became private apartments. The cafe weathered Hurricane Sandy, and it is now open to the public once again.

Ellen S. Auchmuty Building (1885)

142-144 Beekman Street/211 Front Street; designed by George B. Post (1837–1913)

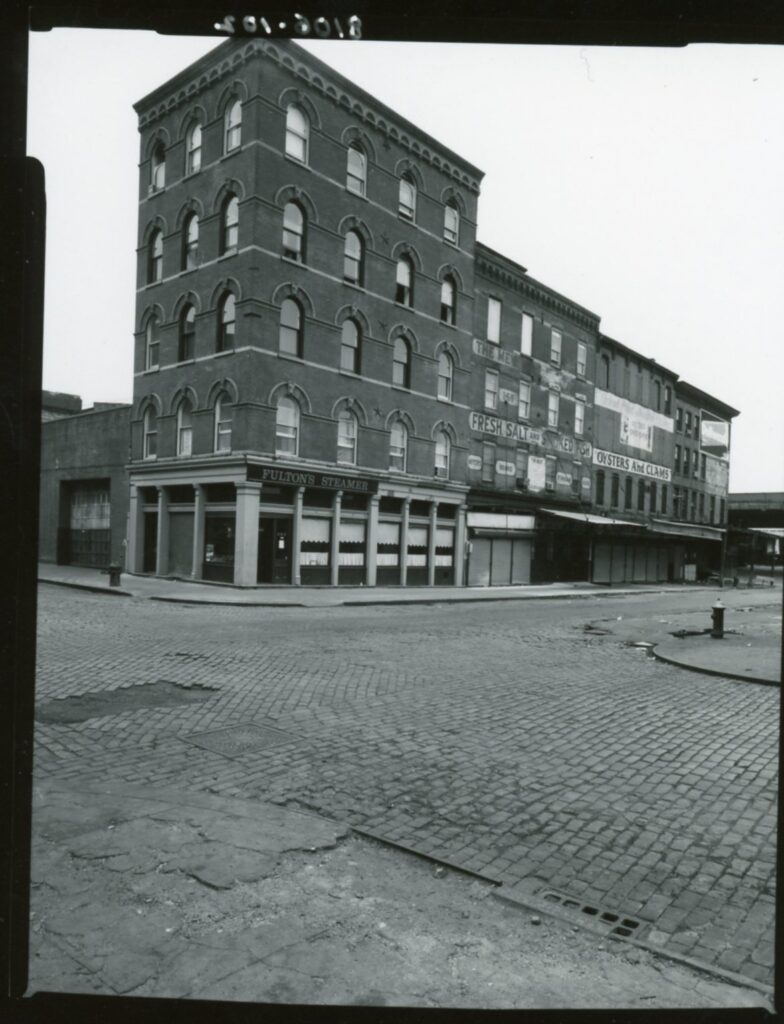

One of the most Interesting structures of the Seaport to me is the Romanesque Revival building that was erected in 1885 for (1837–1927), a Schermerhorn family descendant. For the design of the building, Auchmuty commissioned George B. Post (1837–1913), one of the most prominent New York architects of the late 19th-early 20th centuries. Trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition, Post ran one of the largest and busiest architectural firms in the US, with notable designs including the old New York Times building at Printing House Square (1889), Bronx Borough Hall (1897), and the New York Stock Exchange (1904).

“Our” Peter John Schermerhorn actually bought the lot in 1815 on what was called at the time Crane’s Wharf, renamed Beekman Street in 1822, and the site remained in the hands of his descendants for more than a century.

It appears that no applications for alterations have been filed for the building since it was built, and the Historic American Buildings Survey assumed, in its 1976 report, that the corner building remained, beside general aging, as it appeared when it was first constructed!

142-144 Beekman St., 1981. Photo by Jeff Perkell, South Street Seaport Museum Archive.

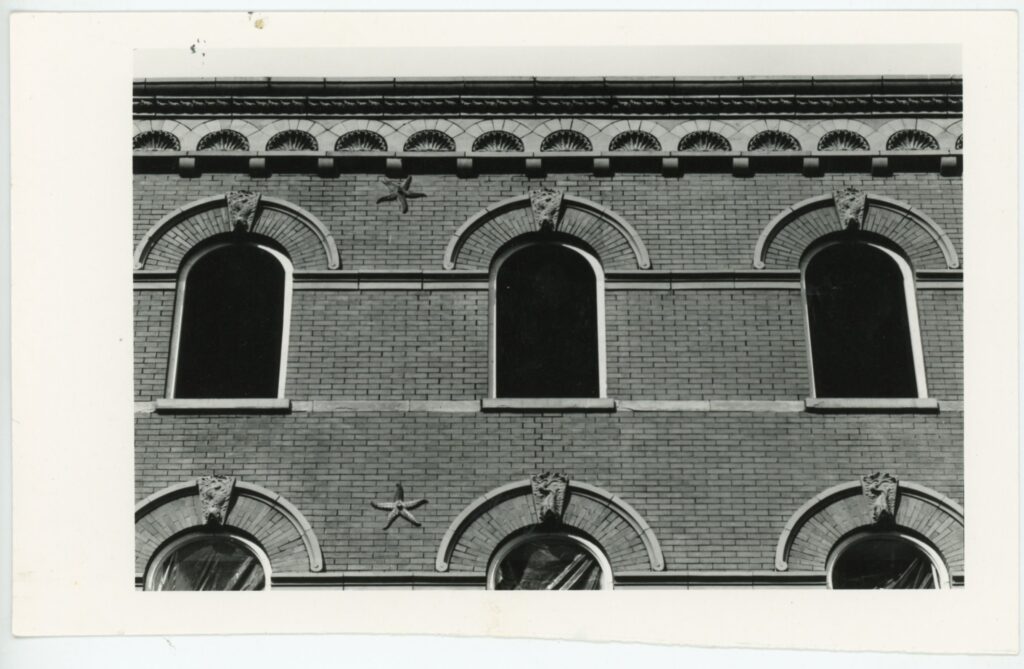

Upon its opening, the building at 142-144 Beekman Street was occupied by businesses associated with the Fulton Fish Market. This connection is strongly visible in the exciting and playful terracotta elements designed by Post: starfish tie-rod washers, fish keystones sporting dolphins, and a cockle-shell roof cornice.[6]Walking Around South Street by Ellen Fletcher Rosebrock, 1974. pp. 44-45.

The address would later house a Western Union telegraph office. It was here that the orders and replies between seafood merchants and customers were received before the days of the telephone.

Left: Building Details, 142-144 Beekman Street, Spring 1981. Photo by Jeff Perkell. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Right: Seaport Museum Walking Tour, 2022

The Ellen S. Auchmuty Building underwent a light restoration in the 1980s and like many other buildings in the neighborhood its occupants changed following the taste of the district’s residents and visitors, including other types of businesses not related to the fish market, including restaurants, and more recently a beloved flower shop.

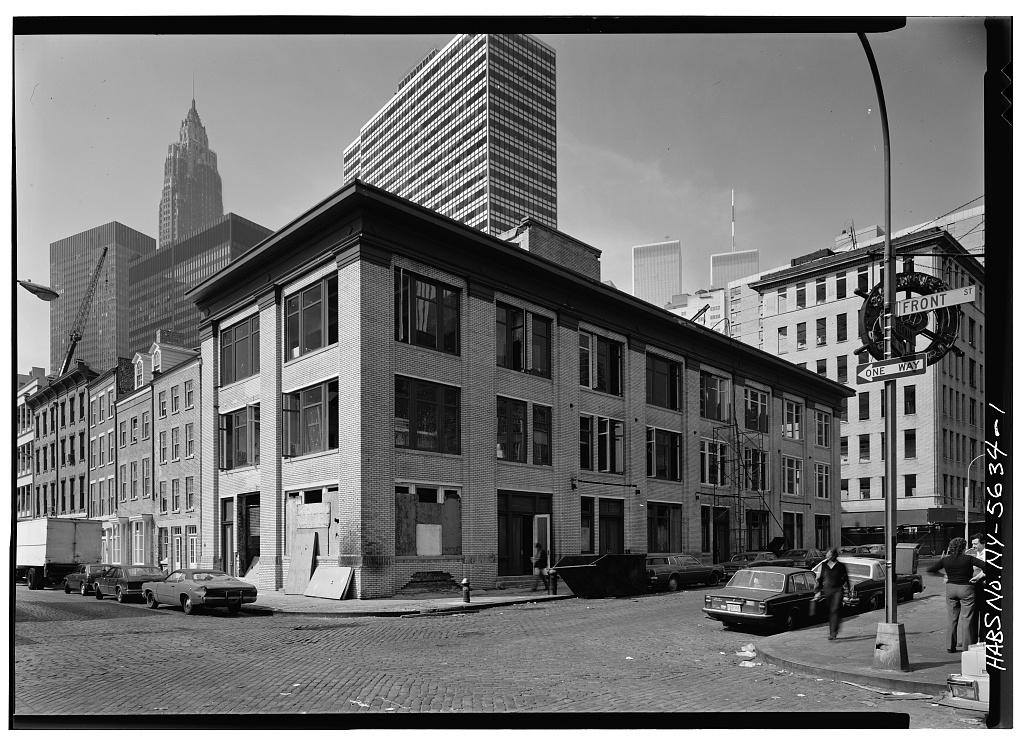

Livingston Building (1914)

127-137 Beekman Street; designed by James S. Maher (active early 20th century)

The only 20th-century building on the block, this three-story cream brick warehouse has changed very little since it was built as a rental property for landowner and Gilded Age society leader Ruth Livingston Mills (1855–1920).

The prominent New York Livingston family, whose members include signers of the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution, held this lot from 1750 until 1944. The family’s wealth was made in part through the participation and perpetuation of slavery—both through trade and by holding people in bondage in New York and Jamaica.

127-137 Beekman Street, New York County, NY. Photo from Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS No. NY-5634 Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Eight early buildings stood on this landfill site until 1914 when architect James S. Maher (active early 20th century) built this yellow brick loft warehouse. Three stories high, the building extends the whole length of the block from Water to Front Streets. Neoclassic details include large tripartite windows between massive, full-height pilasters which have sheet metal capitals. A deeply projecting dentilated cornice of sheet metal crowns the building.

The first occupant of 127-137 Beekman Street was Blackford & Company, which was one of the biggest firms in the Fulton Market for almost thirty years. Founded by Eugene G. Blackford (1839–1905), the company first introduced the New York market to new varieties of fish and improved the methods of freezing, shipping, and storing fish. Blackford was appointed one of the four commissioners of fish and fisheries of the state of New York in 1879. He conducted an investigation into the decrease of oysters in the waters of New York and published papers on whitebait and the question of legislative protection of ocean fisheries!

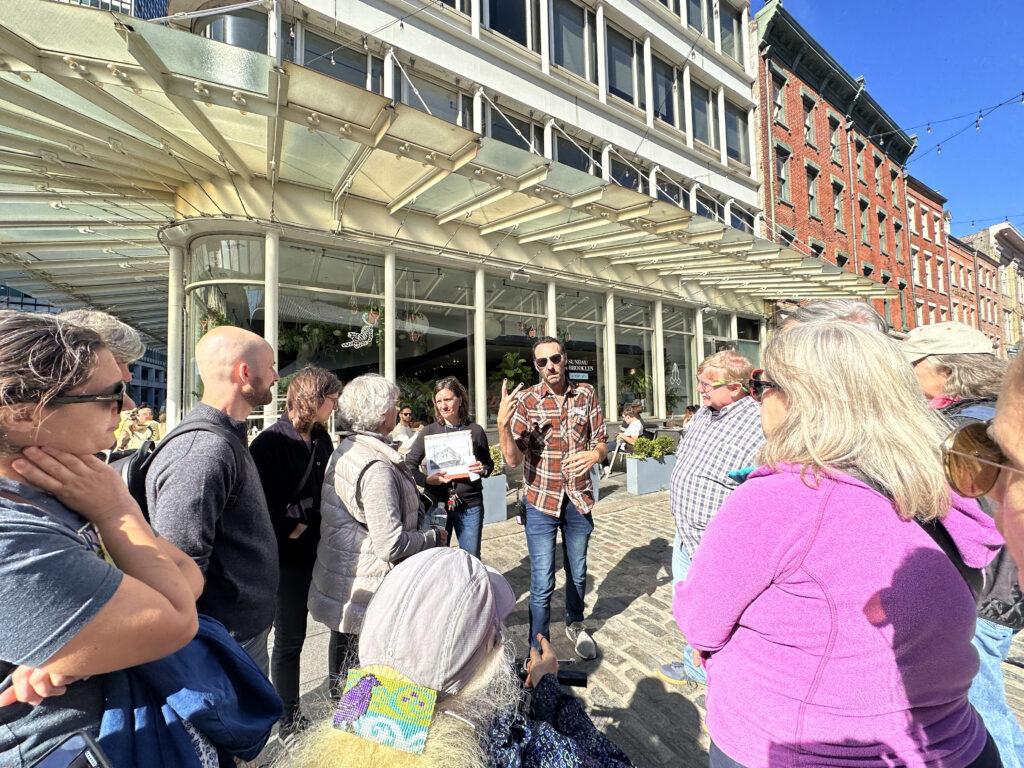

Bogardus Building (1977-1983)

15-19 Fulton Street/201-202 Front Street; Designed by Beyer Blinder and Belle

In the 1950s, the century-old brick buildings that stood on the northwest corner of Fulton and Front streets were torn down to build a vent for a subway tunnel just before its plunge under the East River.

Fulton and Front Street, March 1980. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

In 1975, the planners restoring the block realized the mostly empty lot could be the new site for the 1849 Edward Laing Stores—New York’s first cast iron building by architect James Bogardus (1800–1874)[7]Interesting fact: James Bogardus’ wife, Margaret Maclay Bogardus (1804–1878), had a successful career as an artist. Her career began in England in the 1830s, and blossomed upon her return to … Continue reading.

After the demolition of the Washington Street Market, the building stood there a few years more, until 1971, mostly thanks to its designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

In early 1970s it became critical to demolish it to continue the urban renewal project, but to do so it was deemed necessary to document and preserve the façade. The store’s components were then carefully saved, numbered, and stored on a nearby vacant lot so that the structure could be reassembled on the campus of the new Manhattan Community College.

Edgar Laing Stores, Washington & Murray Streets, New York County, NY. Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.

A few years later, in 1974, however, three men were discovered loading cast-iron panels from the Laing Stores onto a truck in a storage lot at Washington and Chambers Streets. Though 22 broken sections were later recovered in a Bronx junkyard, city officials discovered that almost two-thirds of the façade had already been sold for scrap, at $90 a truckload. The theft became public when Mrs. Beverly Moss Spatt, chairman of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, dashed into the press room at City Hall shouting “Someone stole one of my buildings!” Over a three week period, someone stole more than half of the entire façade, never to be found[8]4‐Ton Cast‐Iron Landmark Facade Panels Stolen Here, June 26, 1974. The New York Times..

The remaining panels were immediately placed under lock and key, and a hybrid Laing building, combining original and recast components, was planned to be erected in the new South Street Seaport Historic District, but, incredibly, all the remaining pieces were stolen again in 1977.

Already partially designed as the framework for the intended Laing Stores, this 1983 steel structure honors the original echoing the same rhythm of columns and beams. Architects at Beyer Blinder and Belle (BBB) designed this building as a corner building that echoes the design of New York’s first cast-iron facade and remains today as a focal point for indoor and outdoor activity at the Seaport.

Left: Bogardus Building under construction, ca. 1982. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Right: Seaport Museum Architecture Walking Tour, 2022.

Additional Readings and Resources

South Street Report, published by the South Street Seaport Museum, Spring 1975.

Historic American Building Surveys (HABS), by National Park Service, 1976.

South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report, 1977.

Membership Newsletter of the South Street Seaport Museum, Vol. 3, No. 1, February 1978.

Schermerhorn Row Block: A Study in the Nineteenth-Century Building Technology in New York City, published by New York State Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Bureau, January 1981.

South Street Seaport, Oculus AIANY, September 1983.

Saved from the Wrecker’s Ball, by Ellen Rosebrock. Seaport, Summer 1983 p. 38.

AIA Guide to New York City, published by Oxford Press, Fifth Edition, 2010.

Support Our Work!

Virtual programs like this one are provided at no cost in order to serve our community in unique and engaging ways, no matter where you might be in the world. Help us make this work possible.

References

| ↑1 | According to the Encyclopedia of New York, William Laight and his son Henry were the first to maintain an extended record of New York weather, beginning in 1788. The New-York Historical Society has the weather diaries of Henry, covering 1795-1803 and 1816-1822, noting the temperature, wind, precipitation and/or clouds, lunar phase and a brief entry about the day’s events. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report, 1977 |

| ↑3 | “A parcel of waterfront real estate that extended from the shore’s low watermark 400 feet out into the water, to be filled in by the owner at their own expense.” Unearthing Gotham, Cantwell and Wall 2001, pp. 225-226 |

| ↑4 | ”The murals of artist Richard Haas are stunningly realistic. Since the 1970s, Haas has created hundreds of trompe-l’oeil murals in cities across the world, from Boston to Chicago, and Miami to Munich. Meaning “trick of the eye” in French, Haas’ trompe-l’oeil masterpieces cover multi-story facades of buildings. These large-scale works appear three-dimensional and life-like, depicting scenes and buildings that the viewer feels they can step right into. Right here in New York City, we have five exterior Richard Haas murals to be mesmerized by. Haas has also done stunning interior murals including inside the DeWitt Wallace Periodical Room at the New York Public Library on 42nd Street. He continues to create smaller-scale paintings and drawings.” The Mesmerizing Trompe L’oeil Murals of Richard Haas in NYC, by Nicole Saraniero, untapped new york. |

| ↑5 | ”The intricate facades of SoHo, once considered merely functional, have since become symbols of urban elegance, embodying a unique blend of industrial strength and artistic beauty. On August 14 1973, the SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District was officially designated as a historic district by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). The district was subsequently listed on the National Register of Historic Places and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1978, and its borders were extended in 2010 to include most of West Broadway and to extend east to Lafayette and Centre Streets. The designation was not only a recognition of the area’s unique architectural heritage, but also a pivotal move that preserved one of the city’s most distinctive neighborhoods.” The SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District: A 1973 Designation That Helped Shape NYC’s Cultural Legacy, by Lannyl Stephens, Village Preservation. |

| ↑6 | Walking Around South Street by Ellen Fletcher Rosebrock, 1974. pp. 44-45. |

| ↑7 | Interesting fact: James Bogardus’ wife, Margaret Maclay Bogardus (1804–1878), had a successful career as an artist. Her career began in England in the 1830s, and blossomed upon her return to America a few years later. Two of her portrait miniatures—depicting Mr. Boardman and Paul Joseph Revere—are in The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection! |

| ↑8 | 4‐Ton Cast‐Iron Landmark Facade Panels Stolen Here, June 26, 1974. The New York Times. |