A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Carley Roche, Collections and Archives Intern

November 26, 2020

Thanksgiving is looking a little different this year with many unable to see family and friends in person. The changes Covid-19 has brought onto our everyday lives, as well as onto special occasions, do not mean that we need to forget why we celebrate today. Although Thanksgiving has a contentious history, one that should never be overlooked, I will focus this post on the heart of the holiday: giving thanks and helping others.

After living in New York City for just over a year now I think the reputation of a tough and cold city is just a façade. Of course, you can always catch someone on a bad day, but I think New Yorkers truly care about the well being of the others they share this wonderful city with. It’s in the city’s history to feel generous and welcoming. The city that helped start a country based on personal freedoms, the city that has welcomed immigrants for centuries, and the city that provides for others in need.

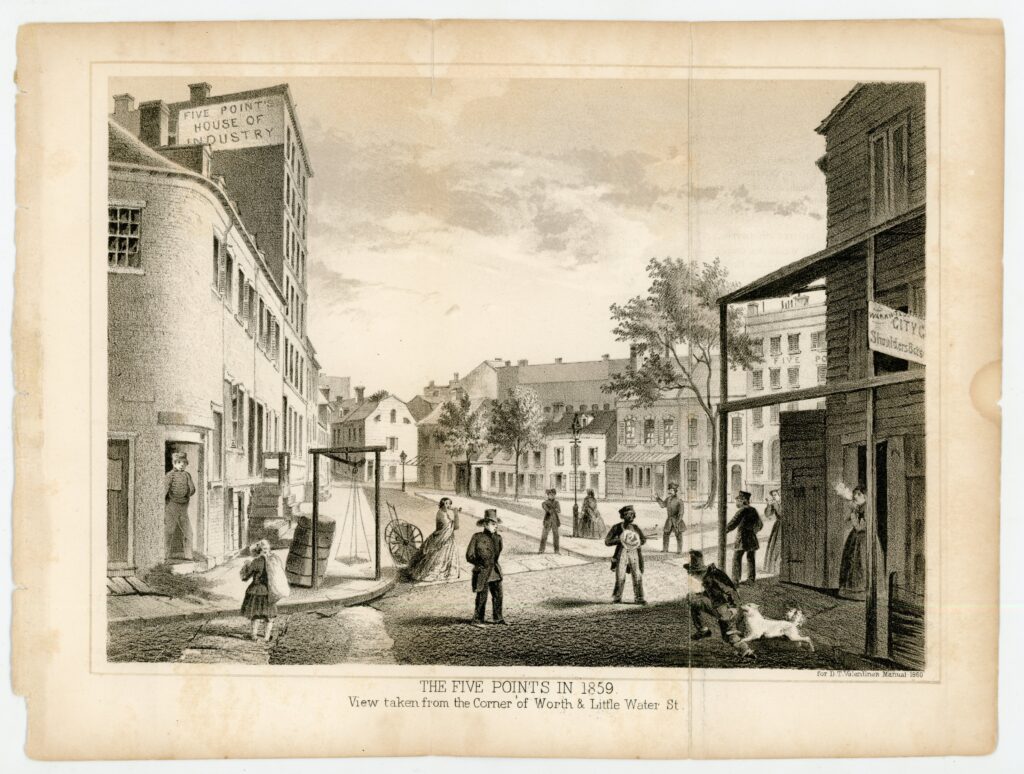

New York City has a history of generosity tied in with an image of harshness. It is an interesting mix, and one that also fits the description of the Five Points House of Industry. A 19th century mission aimed at helping the poor residents of the Five Points neighborhood, the operation was based upon falsehoods and stereotypes of the Lower Manhattan area. As we sit down today for dinner or for a virtual call with our loved ones I think we should take a look back at the historic efforts of Thanksgiving in New York City. Yes, the holidays are different this year, but the spirit behind them has always been the same over the years.

Reputation on the Rise

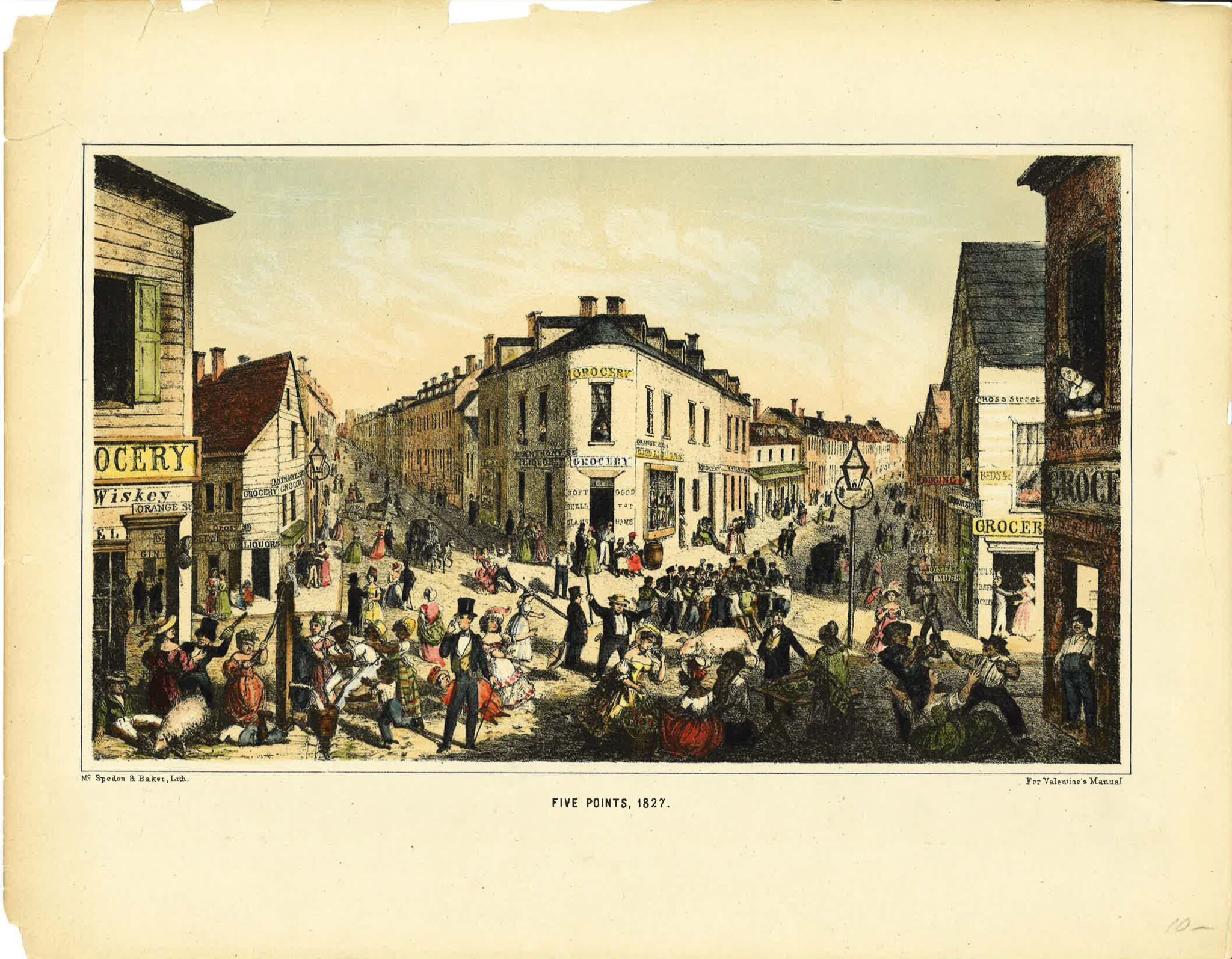

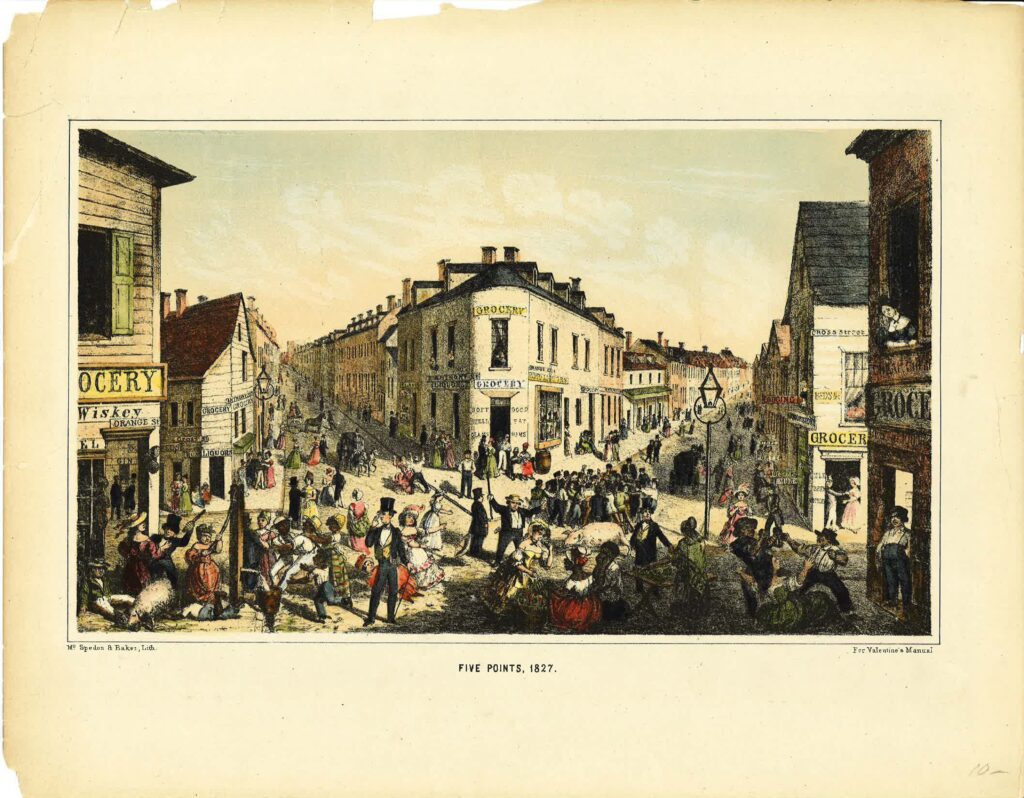

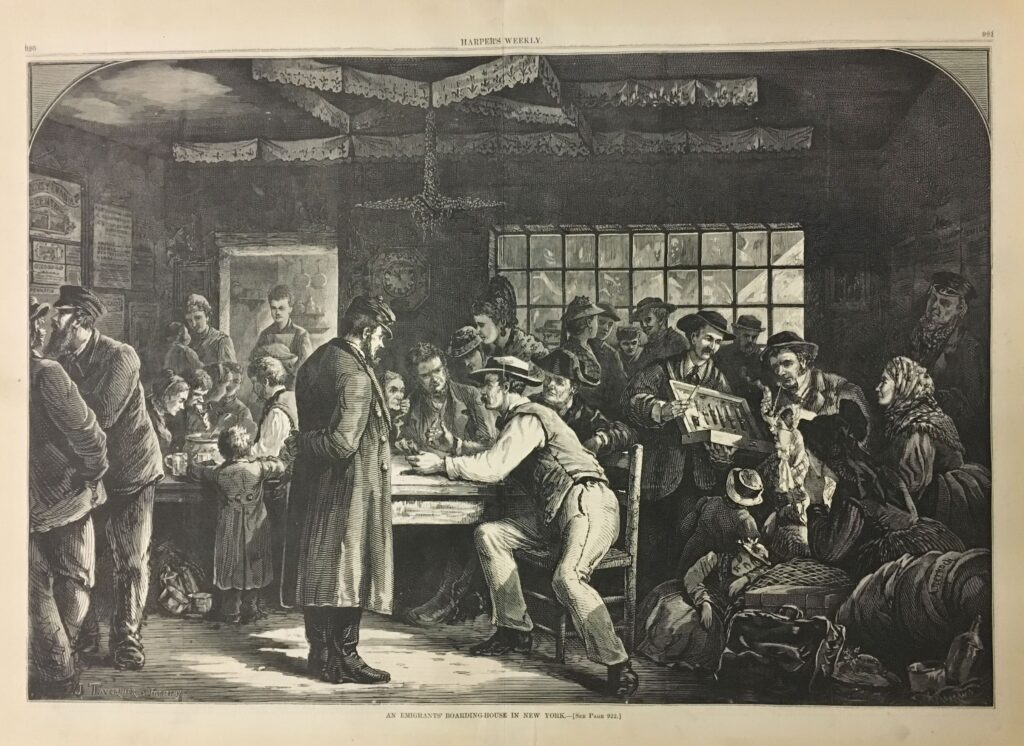

When immigrants began to settle in New York City during the 19th century many, especially those from Catholic Ireland, found themselves in the Five Points neighborhood of Lower Manhattan. Located near modern day Columbus Park near Worth Street and Chatham Square, the Five Points was named after the intersection at Orange, Anthony, and Cross Streets.

The neighborhood was thought to be filled with debauchery and criminality; it was a place for unwanted people of society to fight and steal from each other while living in filth. Across the city (and even across the country), rumors led middle- and upper-class citizens to equate Five Points with a slum of heathenism and vileness.

However, this is what the Protestant middle-class reformers of the time wanted their fellow New Yorkers and countrymen to believe. Yes, the Five Points neighborhood was densely packed with residents and held less than desirable sanitary conditions, but it was far from the revelry and debauchery discussed by those who did not even live in the area. In reality, it was more like a vibrant working-class neighborhood that provided many new immigrants a fresh start in a new country.

Still, the power of rumor outweighs personal investigation and the stereotyped Five Points neighborhood held true in the minds of many New Yorkers. At a time when urban philanthropy was on the rise many felt it to be their duty to take action. The New York Ladies’ Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church answered the call to assist the populations of the Five Points in an attempt to change the area in their vision.

Founding of the Five Points House of Industry

With the religious reformers of the 19th century successfully leading New York society to believe that the Five Points needed saving from itself, it became a simple task to establish the Five Points House of Industry. The New York Ladies’ Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church worked with Reverend Lewis M. Pease to officially open the Five Points House of Industry in 1851.

Their mission was simple: educate those in poverty so they can support themselves, provide food and clothing to those in need, care for and house children, and share Christian ideals without bias from a certain sect. Pease and the New York Ladies’ group wanted to offer change to a neighborhood they deemed uncivilized. The Ladies’ group felt low morals led to rampant poverty while Pease felt a lack of education and job training was at the root of the problem. The Reverend eventually cut ties with the Ladies’ and opened his own House of Industry in the Five Points focusing on educational and job reform.

Despite the rise in philanthropy, many felt that men should not be given aid even if they are living in dire economic conditions. It was believed that men should be able to work their way out of poverty on their own while widows, single mothers, and children are the most fragile members of society and thus need the extra help. Reverend Pease did not agree with these ideals and welcomed men into his Five Points House of Industry. There, Pease provided both men and women “employment in sewing, basketry, shoemaking, and farming” (Heale, pp. 64). Children learned skills such as cooking, cleaning, and print setting to open doors to more respectable positions later in life.

The Five Points House of Industry’s founding began with the intent to reform one of the city’s most notorious sections after rumors and false publications led others to believe it was a den of hopelessness. Despite the general falsehoods, Pease and the House of Industry did help the immigrant residents of the neighborhood with their dedication to improving public health and providing resources to all in need. Pease believed all people- men, women, and children- could benefit from generosity to lead successful and fulfilling lives. Even though the House of Industry workers, and even Pease himself, held to the belief that it is easier to reform children, the doors stayed open to immigrants in search of extra help as they started their new lives.

Thanksgiving at the Five Points

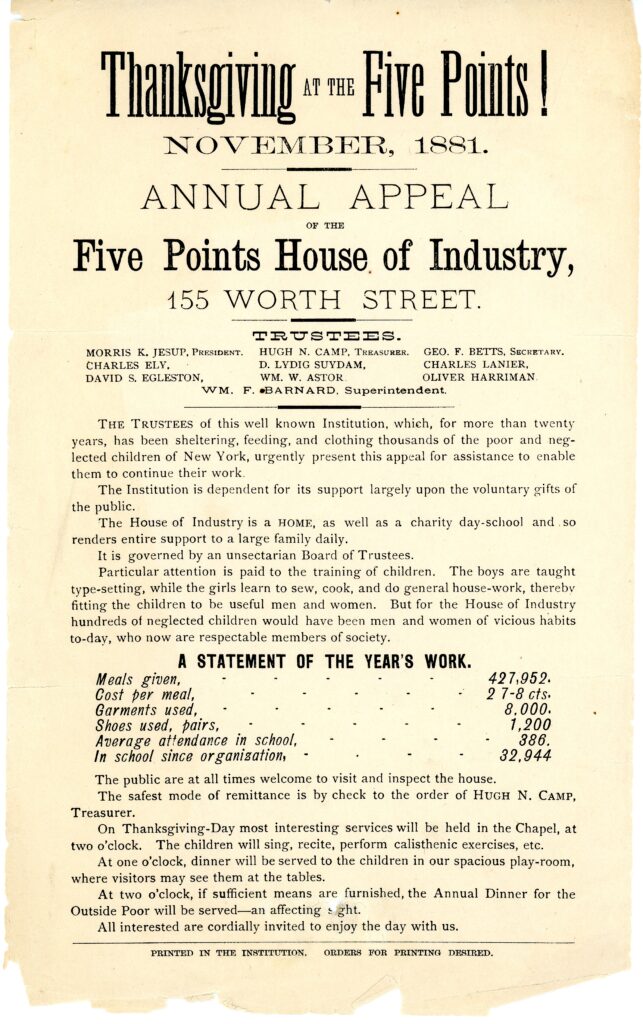

This handbill for the Thanksgiving of 1881 at the Five Points House of Industry shows the success of the establishment’s original mission. Thirty years after its founding the House of Industry continued to provide children and adults with basic necessities: food, clothing, shelter, and education. Relying on donations and public generosity the Five Points House of Industry opened its doors to new immigrants in an attempt to better their lives in America. Through donations and training, immigrants in the Five Points neighborhood could focus on plans for their futures rather than surviving day-to-day.

But this handbill also reminds us of the tenuous reasonings behind the founding of the Five Points House of Industry. Institutions like this one, while certainly accomplishing good deeds, opened their doors in poor neighborhoods in an attempt to reform entire sections of cities in a certain image: an image that tended to go completely against the neighborhood’s current social structure. The Five Points, for example, was a diverse area of Lower Manhattan that saw many Black Americans and White immigrants mix in social and business settings. The House of Industry worked with the New York upper-class to segregate the Five Points and to ensure children were raised in certain types of families- namely, white and Protestant.

While the handbill lauds the accomplishments of feeding, clothing, and educating the children in the Five Points we cannot forget that many of the philanthropic institutions at the time had an agenda at work. History is a complicated subject with every passing year revealing more truths behind topics we once believed to know everything about. We can certainly applaud the donations, the provided education, and the shelter given to those at the Five Points House of Industry while still allowing ourselves to acknowledge that discourse is continually needed to understand the full story.

Conclusion

Thanksgiving is a time of food and warmth, giving and receiving. Exactly 139 years after the printing of the handbill above, we still hold true to these ideals today. This year especially, when so many have lost so much, we should remind ourselves just how grateful we are to be able to provide for our fellow neighbors. In spite of the House of Industry’s beginnings, it created a space that allowed for nourishment, education, and the establishment of foundations in America.

Whether we are able to sit down and have a small gathering with loved ones or if we are double-checking that our phones and computers are fully charged for a lengthy video call we need to remember that today is all about thankfulness and giving to others. I think we should remember this New York generosity, despite the difficult year we have all faced so far.

While the Five Points House of Industry certainly has a gray history in their attempts to reform the neighborhood it ultimately stood for education, work training, and good health among the population. Giving these stepping stones to new immigrants opened doors to more opportunities in a time when many were looked down upon due to their nationality or race. Providing for and welcoming others has always been a New York City trait that I hope will continue on for generations to come.

Sources and additional readings

OUR CITY CHARITIES–No. III.; THE FIVE POINTS HOUSE OF INDUSTRY published on The New York Times on February 22, 1860.

Life in Mid-19th Century Five Points by the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning at The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

The Rhetoric of Reform: The Five Points Missions and the Cult of Domesticity by Robert Fitts, published on Historical Archaeology Vol. 35, No. 3, Becoming New York: The Five Points Neighborhood (2001), pp. 115-132.

Patterns of Benevolence: Associated Philanthropy in the Cities of New York, 1830-1860 by M.J. Heale, published on New York History Vol. 57, No. 1, (January 1976), pp. 53-79.

Five Points District, New York City, New York (1830s to 1860s) by Deborah McNally, published by Black Past on December 2, 2007.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.