The Story of the Knickerbocker Ice Company

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Martina Caruso, Director of Collections and Exhibitions

February 5, 2026

On mornings like today—when the air bites and the rivers skim over with ice—it is easy to feel Winter as something uncomfortable and unavoidable. Yet for New Yorkers in the late 19th century, cold temperatures were not just endured; they were put to work. Long before electric refrigeration, Winter transformed rivers, ponds, and lakes into vital sources of ice, which was harvested, stored, and shipped to keep food fresh and businesses running through the warmer months.

Today’s frigid temperatures offer a glimpse into a time when Winter itself powered an essential trade—one that shaped daily life, commerce, and the working waterfront of New York City in the decades before modern refrigeration changed everything: ice harvesting. Ice harvesting was a seasonal industry that relied entirely on sustained cold, careful timing, and skilled labor. When ice reached the proper thickness, crews moved onto frozen surfaces with saws, chisels, and horses, cutting vast grids of gleaming blocks that would soon make their way into icehouses, markets, and homes.

There is so much to tell about this resilient, hardworking industry—one that shaped daily life and commerce throughout the Hudson Valley, New York City, and the entire Northeast coast of the United States. Read along as I share some of its many facets through the material culture and archival records preserved within the Seaport Museum’s collections and archives.

Producing and storing ice is a practice that goes back to ancient times. In Asia and other parts of the world, the process was achieved by controlling evaporation[1]Producing and storing ice through controlled evaporation involves leveraging low humidity and radiative cooling to induce freezing, often using methods like nighttime cooling in shallow pools, … Continue reading, but in America, the fast-growing ice harvesting industry drew from naturally-produced ice in cold weather. This is credited to the “Ice King of Boston,” a man named Frederick Tudor (1783–1864) who, between 1805 and 1836, developed technical advances that made ice harvesting and storage profitable, creating a mass market for ice. Through tireless experimentation, Tudor reduced loss from ice melt in storage from 66% to 8%, and created markets for shipping his product in southern states and the Caribbean.

One of Tudor’s employees, Nathaniel Wyeth (1802–1856), patented the horse-drawn ice cutter: the first tool to cut even-sided, regular blocks of ice. Before his invention, ice was hacked out in irregular chunks, which led to much loss from melt and inefficient shipping and storage. Wyeth’s innovation made a viable ice industry possible.

Additionally, much of the impetus for this growth is traceable to the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, giving New York City access to the western market. While the canal was an outgrowth of mercantile capitalism, it ushered in a subsequent economic regime during which New York became “the center of the world’s great industrial regions.”

Rockland Lake and South Street

Before the early 19th century, ice in New York was available only in the Winter months, when ice froze in lakes. If in the Summer you wanted to cool off with a cold lemonade or an ice cream, there was no practical way to do so—until a few imaginative men figured out a way to do just that. Using ice from Rockland Lake, on the west bank of the Hudson River, Knickerbocker Ice Company was started. But why Rockland Lake? What about this lake enabled a flourishing ice industry? And what is its connection to the South Street Seaport?

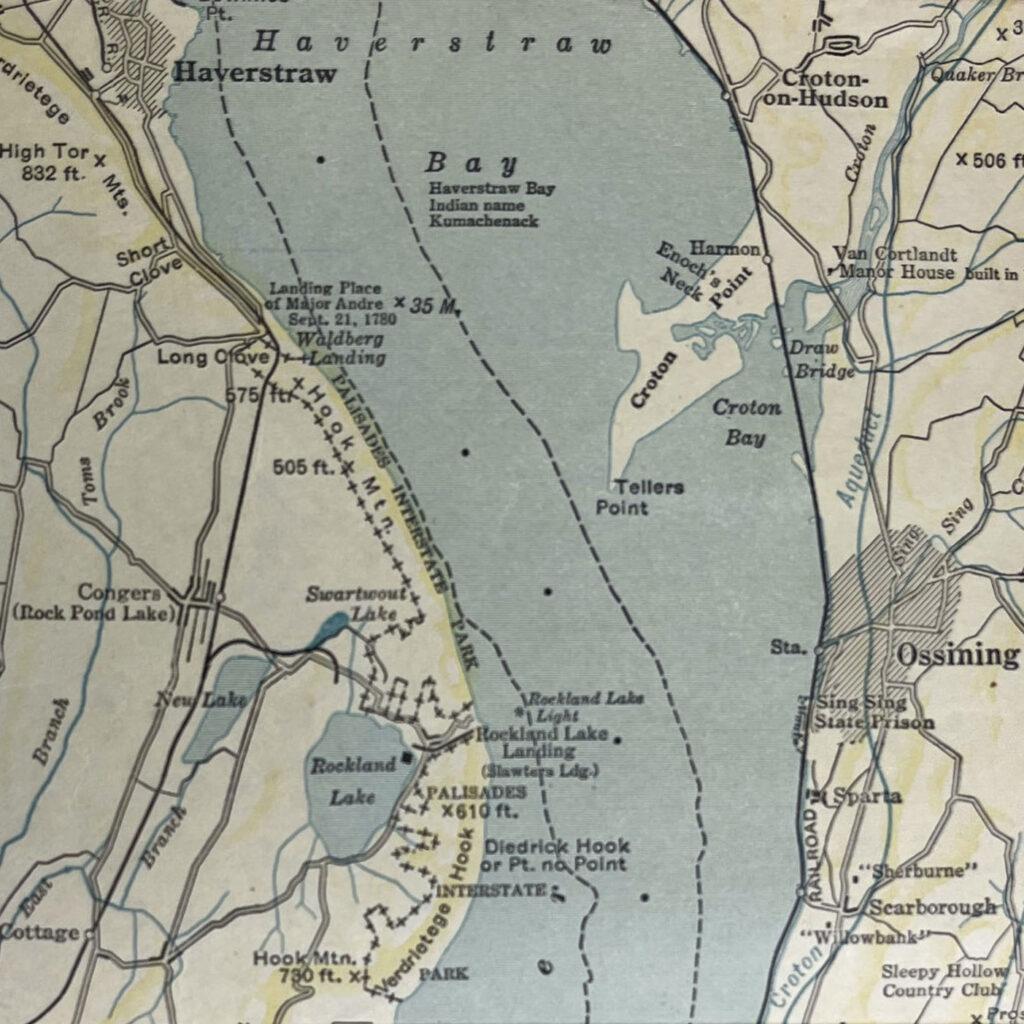

Rockland Lake has a geographical and strategical position along the Hudson River, as the Palisades curve west near Haverstraw to form the High Tor Ridge, creating a natural territorial boundary.

South of Newburgh, the Hudson River is unsuitable for ice harvesting, as a tidal estuary it contains a mix of fresh and salt water in the lower part of the valley. Rockland Lake, on the other hand, was fed by a spring and remained largely unpolluted.

Detail from Rand McNally & Company, publisher. “Tourist Map of Hudson River Along the Route of the Hudson River Day Line” ca. 1923, p.9. Seamen’s Bank For Savings Collection 1991.077.0064

The story of Rockland Lake begins with the region’s Indigenous people, who likely used the site seasonally for fishing and oystering. Indigenous people called Rockland Lake Quaspeck, though the meaning of the word has been lost. Early settlers referred to it simply as “The Pond.” The name Rockland Lake wasn’t adopted until the 19th century.

On May 30, 1694, William Welch (1640–1720) and Jarvis Marshall (active late 17th century) purchased 5,000 acres called Quaspeck from seven Indigenous men[2]”Pre-Revolutionary Dutch Houses and Families in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York” by Rosalie Fellows Bailey, pp. 173–192.. And Governor Benjamin Fletcher (1640–1703)[3]Benjamin Fletcher (May 14, 1640–May 28, 1703) was the colonial governor of New York from 1692 to 1697. Fletcher was known for the Ministry Act of 1693, which secured the place of Anglicans as the … Continue reading confirmed their patent, or contract, under the reign of William III and Mary II who were joint monarchs of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1689 to 1702. The annual rent was one peppercorn for five years, then 20 shillings per year.[4]“The history of Rockland County” by Frank Bertangue Green, 1852–1887.

In 1711, John Slaughter (active early 18th century) purchased land near Rockland Lake and established a ferry landing that came to bear his name. Like other landings closeby, Slaughter’s Ferry served both passengers and freight. A range of small craft—including flat-bottomed boats and small sail-powered vessels called periaguars—served the river here. The area became the most strategically important crossing during the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Army, George Washington, and even the captured spy Major John André (1750–1780) all crossed there.

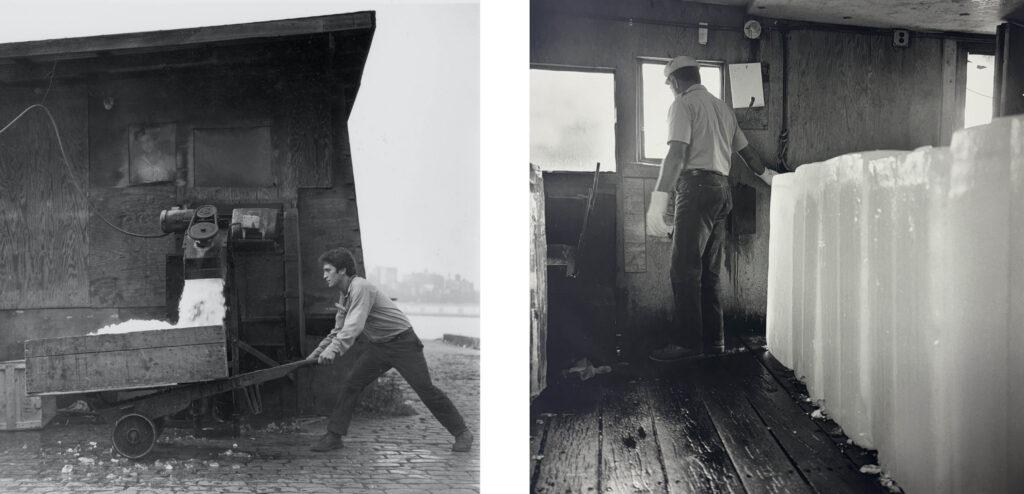

By the 1830s, the landing became critical for transporting pure, clean ice to the city in various ice storage houses, including at South Street. At the South Street Seaport, the ice industry was driven largely by the enormous demand for refrigeration at the Fulton Fish Market. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the market depended on ice houses and suppliers to keep the daily catch fresh during transport and sale, making ice an essential link in the city’s food economy.

Left: Barbara Mensch (American, b. 1950). “Beekman Dock Icehouse” ca. 1981 (original negative), 2008 (print). Museum Purchase 2008.005.0024

Right: Barbara Mensch (American, b. 1950). “Icehouse Interior, Early Morning, Beekman Dock” ca. 1981 (original negative), 2008 (print). Museum Purchase 2008.005.0023

The Knickerbocker Ice Company

In 1835, John J. Felter (1808–1897), John G. Perry (1799–1893), and Edward Felter (1804–1841) came upon a frozen lake in Rockland County, cut out a sloop-sized load of ice and sold it at nearly 100% profit. In 1836, these same three entrepreneurs, along with interested investors, formed Barmore, Felter & Co. They built a dock, along with a small ice house that could store up to 300 tons of ice, and a companion ice house in New York City, in order to distribute it.

The ice harvested from Rockland Lake was of remarkable quality—pure, clear, and untouched by pollution from nearby factories. Because of this, it earned the nickname “white gold.” Yet, there was one challenge: at the time, people simply didn’t use ice in the way we do today. Ice could only be gathered in Winter, and no reliable method existed to preserve it for the warmer months. If ice was needed, one went to a frozen cistern or well and chopped out a piece on the spot.

For the most part, only hotels, butchers, and fishmongers made regular use of ice. The average household preserved food by drying, canning, brining, or smoking. Hotels, however, quickly recognized the potential of a year-round supply of pure, clean ice. Noting the exceptional quality of Rockland Lake ice, the Astor House—New York’s first luxury hotel—featured it on its menus in 1836, transforming it into the most sought-after ice brand in the City.

Barmore, Felter & Co. solidified its position through strategic acquisitions and renaming the company “Rockland Lake Ice.” But the success of Barmore, Felter & Co. was not without its challenges. Eventually, others caught on to the lucrative possibilities of this enterprise and began a ferocious competition. By 1840, several companies fought for control of Rockland Lake. Property was bought up around the lake by different interests in order to claim exclusive rights to the ice that touched its shores.

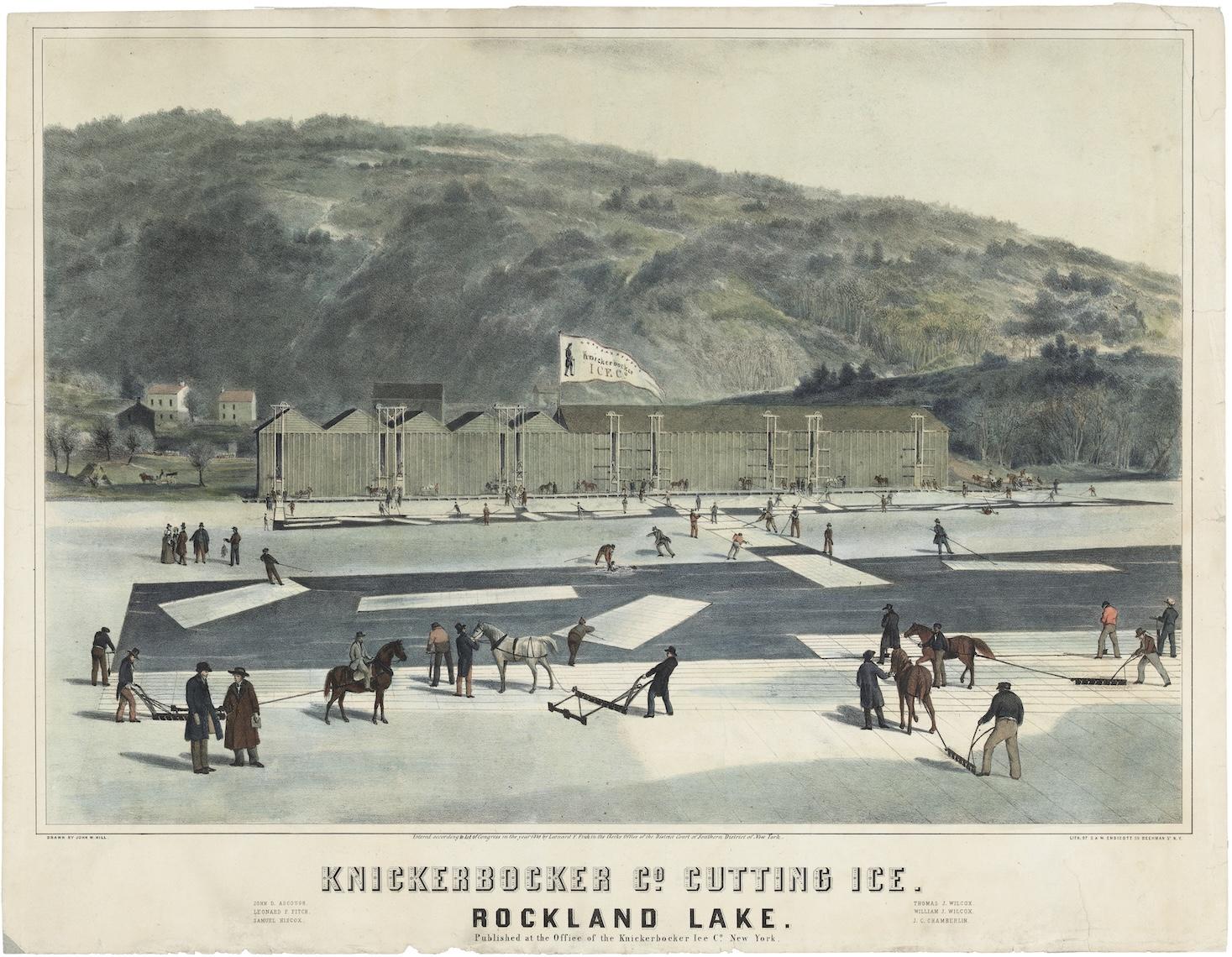

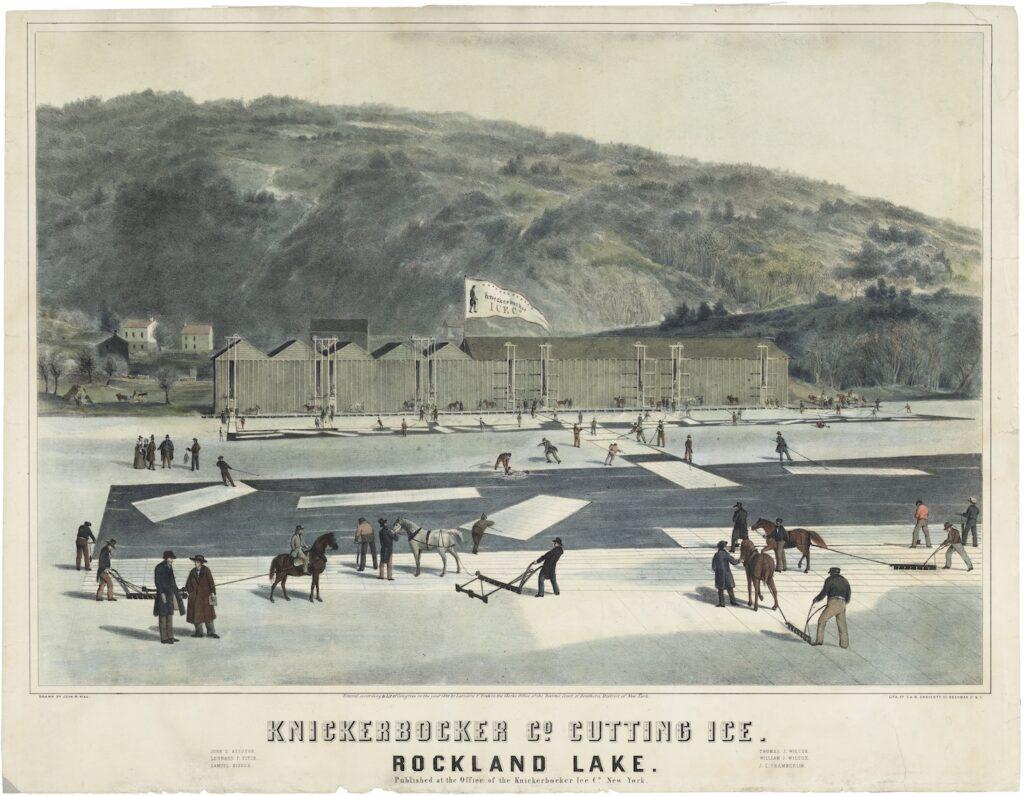

G. & W. Endicott, lithographer. “Knickerbocker Co. Cutting Ice. Rockland Lake.” 1846. Museum Purchase 1997.014.0015

Finally, in 1855, three competing Rockland Lake ice companies joined forces to form the Knickerbocker Ice Company, aiming to “collect, store, and preserve ice for transport to the City of New York.” This strategic collaboration marked a turning point in the consolidation of the ice industry and made significant improvements to quickly harvest and prolong the life of ice. Ice was harvested when it had reached its desired thickness of 14–16 inches, usually at the end of January and during February. It took about three weeks, employing between 400–600 people.

Ice was stored in ice houses that were immense hanger-like buildings, up to 300 to 400 feet long, 100 feet in depth, and were three or four stories high. Many had double walls packed with insulating materials such as wood shavings, sawdust, or hay, which would also be packed around the ice blocks. In addition, the ice houses were usually painted a brilliant white to reflect the sun and further retard melting. A properly packed ice harvest could stay in storage from two to three years![5]”Cultural Resources Investigation. Ice Harvesting Industry Remains Located on Property Belonging to the U.S. Corps of Engineers, New York District” May 1990, p. 5. Seaport Museum Library, … Continue reading

Overall, the City bought 75,000 tons of ice in 1855, and by the 1880s this figure had reached 1.5 million tons. Approximately 135 ice houses were constructed between New York and Albany, preserving and providing ice to the New York City market.

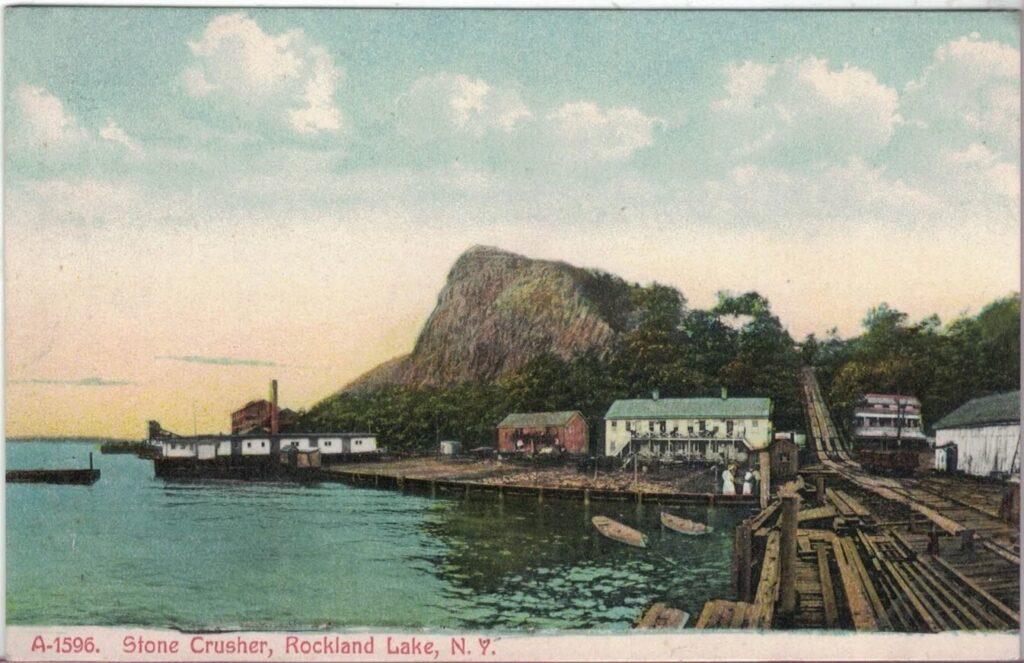

In 1858, a mechanized and gravity-fed ice railway and train system solved the problem of how to get ice from Rockland Lake over the brow of the Palisades to the Hudson River fast and safely.

The first step involved manually loading ice from ice houses onto “cars.” Horses pulled the cars to the end of a wooden chute leading up to the Village of Rockland Lake. A nearby engine house provided power to pull the cars up the chute.

“Stone Crusher, Rockland Lake, NY” early 20th century. Postcard Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

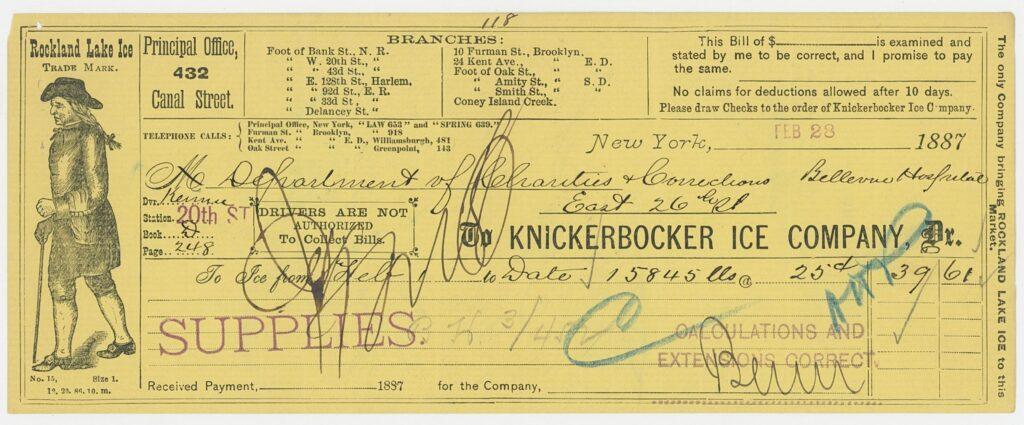

These developments elevated Knickerbocker to the position of king of the ice industry, supplying ice as far away as New York City and its surrounding suburbs. By the 1880s, the company owned 60 barges capable of transporting more than 40,000 tons of ice and employed some 1,000 horses and 500 wagons to deliver its product. A 13,000-square-foot manufacturing and repair shop at the end of West 20th Street in New York City kept Knickerbocker’s vast operation running—and the ice moving.

“Knickerbocker Ice Company invoice for Department of Charities & Corrections Bellevue Hospital” February 28, 1887. Gift of Mr. Stephen Freidus 2001.006.0089

The Knickerbocker Ice Company solidified its dominance by investing in large ice houses storing over 100,000 tons and a cleverly designed ice train along the northeastern lake shore, which served over 1/3 of the demand for ice in New York City and Philadelphia.

Harvesting Workforce and Tools

Ice harvesters, or “ice fishers,” as they were sometimes called, numbered some 400–600 during the heyday of the Knickerbocker Ice Company. The work of ice harvesting was wet, cold, and hazardous. Accidents of all sorts happened. Sometimes, workers had their limbs crushed while moving heavy blocks of ice.

It took about three weeks in January and February to fill the ice houses. Some of the ice was sent by train from Rockland Lake to the nearby Congers, Rockland County. The rest was held until the Hudson River was ice-free for shipping to New York City. In the Summer months, 80 or so employees worked 12-hour days to move ice from the ice houses to barges on the Hudson River for shipment to the City. The men loaded one boat per day with about 2,000 tons of ice.

Ice production required the efforts of many hard-working people. Over the course of three weeks, workers had to clear, mark, cut, saw, float, lift, and pack ice that would last until the following Winter. Here’s how they did it:

Thomas A. Edison, filmmaker. “Ice Harvesting at Rockland Lake” February 24, 1902.

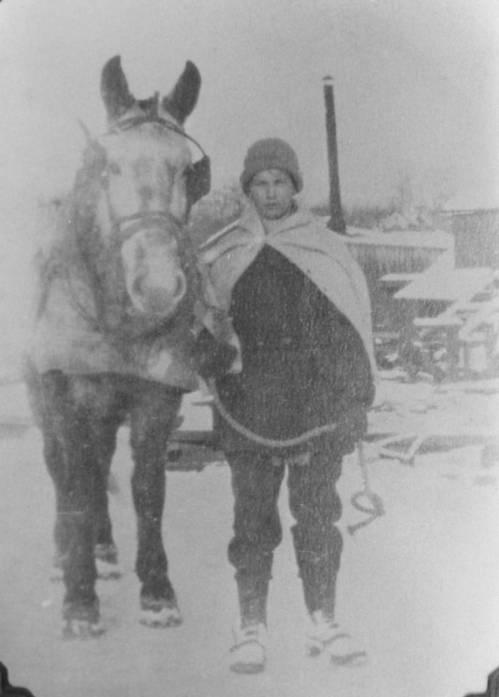

The day began around 4am and pay averaged around $1.00 per day for laborers and $2.00 for skilled mechanics. Aside from the fishers, the company employed mechanics, horsemen, and boatmen. Even as the market for natural ice declined in the beginning of the 20th century, ice harvesting was a good occupation.

In 1907, Josephine Hudson (1898–1996), at age 19, was the only woman working for the Knickerbocker Ice Company.

She got a job with the company by disguising her long hair; she dressed as a boy and called herself “Jo.” Her house still stands, though in disrepair, on the northeast side of the lake.

“Josephine Hudson in Rockland Lake, NY” ca. 1920. Nyack Library Local History Collection, New York Heritage Digital Collections.

As you can see in the above Thomas Edison films, workers used an array of tools to remove the ice from Rockland Lake and to store it in the icehouses. Here’s what might be found in the Knickerbocker tool shed that we preserve in the Museum’s collections. This group of tools and implements related to the ice industry of 19th century America were all collected locally and, by all indications, were used in the commercial ice harvesting trade in the general area of the Port of New York, Hudson River Valley, and Lower New England.

“Ice Harvesting Tools” late 19th century. Gift of Peter A. Aron 1988.068

Food and Commerce Impacts

Ice production and preservation was responsible for transforming the food industry, and for the first time a butcher and the fishmonger could keep meat and fish fresh, vegetables could be transported longer distances, and hotels could ice beverages on the hottest of days.

Another significant consumer of ice was the brewing industry, which used ice in regulating the temperature of fermentation so that beer could be made year-round, rather than in a limited number of months. As the meat-packing industry grew, it too consumed large quantities of harvested ice.

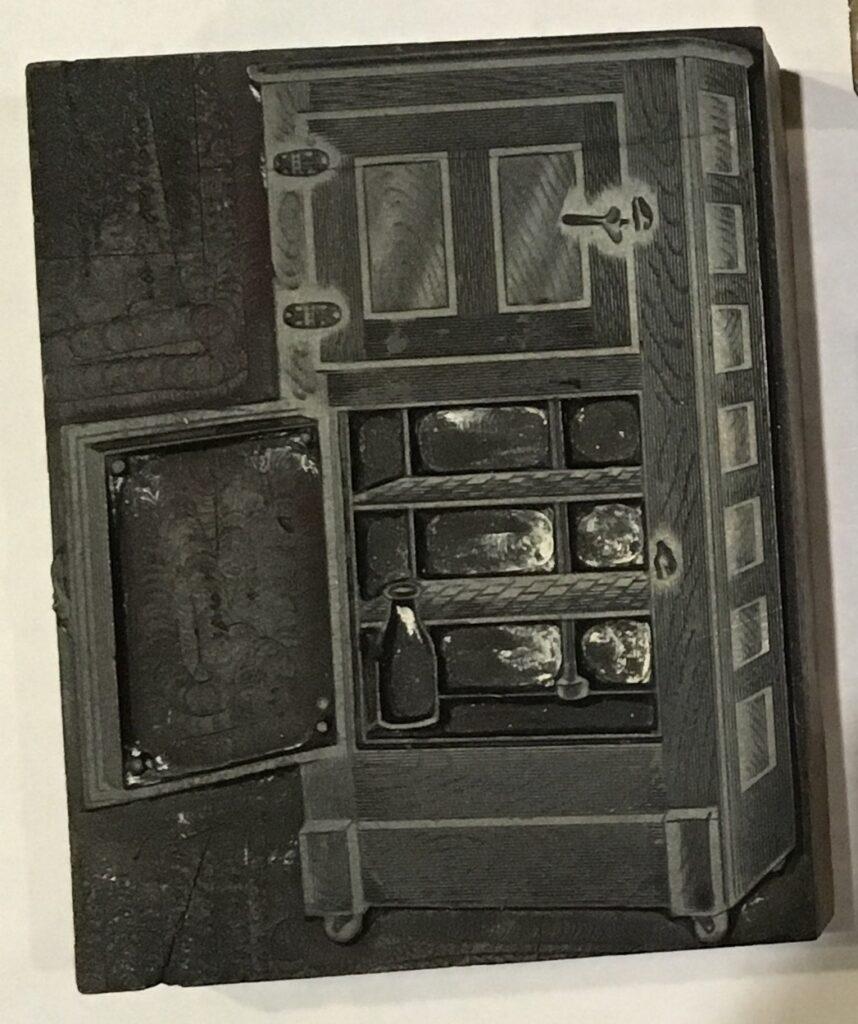

In 1885, everyone could purchase an icebox and keep their groceries fresh longer. Most kitchens had one. They looked a bit like a modern refrigerator, standing about three or four feet high, often with two doors in front.

A block of ice rested in one compartment and food would be placed in another. Depending upon how hot it was outside and how well the icebox was insulated, the block of ice would last from about 5 days to a week.

[Printing Plate of an Ice Box] early 20th century. Gift of John E. Bohlander 1985.029.0012

Knickerbocker Ice was delivered by horse and wagon, and the iceman delivered it to homes. He would drive his wagon down the street and stop by your house. Sometimes the iceman would put the ice in the icebox and sometimes people who lived in the house would take the ice with ice picks from the iceman and place it in their icebox themselves.

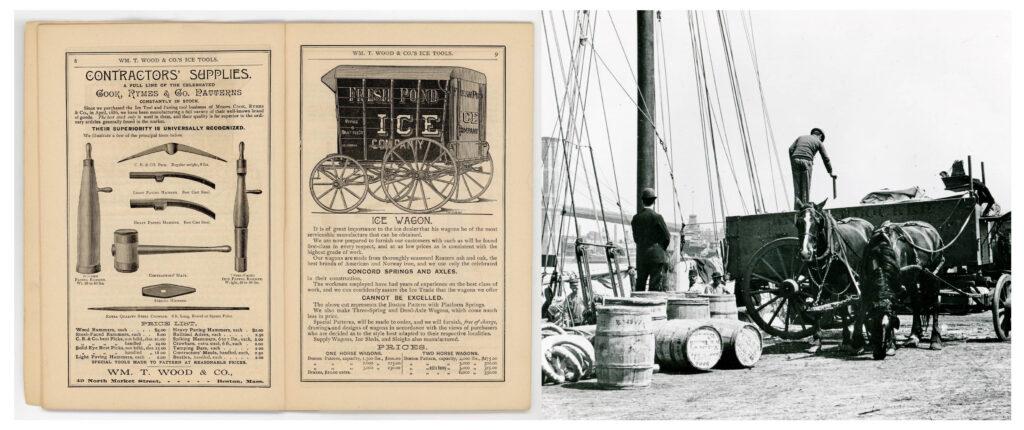

Left: “Wm. T. Wood & Co. Manufacturers of Ice Tools Catalog” 1888, pp. 8–9. Gift of Peter Neill 1997.011.0078

Right: [Knickerbocker Ice Company wagon on South Street pier] n.d. (original ca. 1890). South Street Seaport Museum Archives H20-0141

In the late 19th century, many Winters were so warm that ice either didn’t form or was too thin to harvest. One such year was 1890, and the Knickerbocker Ice Company had to “import” ice from upstate and from as far away as Maine to meet demand. As a result of this “ice famine,” the company was bought by Charles W. Morse (1856–1933)[6]Charles Wyman Morse (October 21, 1856–January 12, 1933) was an American businessman and speculator who committed frauds and engaged in corrupt business practices. At one point, he controlled 13 … Continue reading in 1891 and became part of the newly-formed American Ice Company.

In the early 20th century, people started using electricity to refrigerate foods and although expensive, the days when families relied on the iceman and iceboxes were drawing to a close. By the 1920s, refrigerators were becoming affordable to most families and took the place of iceboxes. In 1924, the last of the ice was harvested from Rockland Lake and the clomping sounds of the horse-drawn wagons bearing deliveries passed into history.

Left: [Fulton Fish Market worker checking crates] Spring 1947. South Street Seaport Museum Archives H23-0045

Right: Knickerbocker Ice Company, 226 Front Street, ca. 1970. South Street Seaport Museum Archives H102-0941

As demand for natural ice declined, so did ice harvesting. In 1924, harvesting ceased at Rockland Lake. While the ice houses were abandoned or being demolished, in 1926 the workers accidentally started a fire that burned down the entire operation and threatened the Rockland Lake and Landing village. Afterwards, the Knickerbocker Ice Company continued in business for many years. By 1928, they were manufacturing ice in 10 different plants in Brooklyn using New York City tap water.

Many other ice houses fell into decay and ruin. Today, the material remains of the ice industry lie buried under landfill, submerged in the mud of the riverbank, or covered by thick vegetation.

In 1963, the Palisades Interstate Park Commission acquired 360-acres around Rockland Lake and along the Hudson River to preserve this important piece of history. Each January, it hosts the Knickerbocker Ice Festival, a celebration of the vanished ice industry and its unique place of interest in Rockland.

Additional Readings and Resources

“The history of Rockland County” by Frank Bertangue Green, 1852–1887.

“The Knickerbocker Ice Company” Rockland County Journal, Volume XXIX, 8 February 1879.

“The Ice Industry of the United States” by Henry Hall, 1884. Tenth U.S. Census, 1880, Volume 2.

“Ice Tools Catalogue and Price List” by William T. Wood, 1888.

“The Rise of the Port of New York, 1815–1860” by Robert G. Albion, 1939. Reprint edition 1961.

“Walking Around In South Street” by Ellen Fletcher Rosebrock. South Street Seaport Museum, 1975.

“Rockland Lake and the Hudson Valley Ice Industry” Hudson Valley Magazine, December 10, 2010.

“Ice Harvesting at Rockland Lake” Hudson River Maritime Museum History Blog, November 1, 2021.

References

| ↑1 | Producing and storing ice through controlled evaporation involves leveraging low humidity and radiative cooling to induce freezing, often using methods like nighttime cooling in shallow pools, evaporative supercooling, or advanced thermal energy storage systems. To learn more about it, read “Evaporative supercooling method for ice production” in Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 37, May 2012, Pages 120–128 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Pre-Revolutionary Dutch Houses and Families in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York” by Rosalie Fellows Bailey, pp. 173–192. |

| ↑3 | Benjamin Fletcher (May 14, 1640–May 28, 1703) was the colonial governor of New York from 1692 to 1697. Fletcher was known for the Ministry Act of 1693, which secured the place of Anglicans as the official religion in New York. He also built the first Trinity Church in 1698. Under Col. Fletcher, piracy was a leading economic development tool in the city’s competition with the ports of Boston and Philadelphia. New York City had become a safe place for pirates. Fletcher was eventually fired for his association with piracy. |

| ↑4 | “The history of Rockland County” by Frank Bertangue Green, 1852–1887. |

| ↑5 | ”Cultural Resources Investigation. Ice Harvesting Industry Remains Located on Property Belonging to the U.S. Corps of Engineers, New York District” May 1990, p. 5. Seaport Museum Library, F127.H8 N4 99 |

| ↑6 | Charles Wyman Morse (October 21, 1856–January 12, 1933) was an American businessman and speculator who committed frauds and engaged in corrupt business practices. At one point, he controlled 13 banks. Known as the “Ice King” early in his career out of New York City, through Tammany Hall corruption he established a monopoly in New York’s ice business, before buying several shipping companies and moving into high finance. His attempt to manipulate the price of copper-shares set off a wave of selling that developed into the Panic of 1907. Jailed for violating federal banking laws, he faked serious illness and was released. Later, he was indicted for war profiteering and fraud. |