A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

October 29, 2020

Have you ever wondered how our collections and archival material were collected? And after new acquisitions enter into the Museum how they are cared for? For this episode of “Collections Chronicles” I decided to concentrate on one of my favorite collections at the Museum, the Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard Collection.

But before we dive into the details of this acquisition, let me tell you about the history of this New York City maritime enterprise.

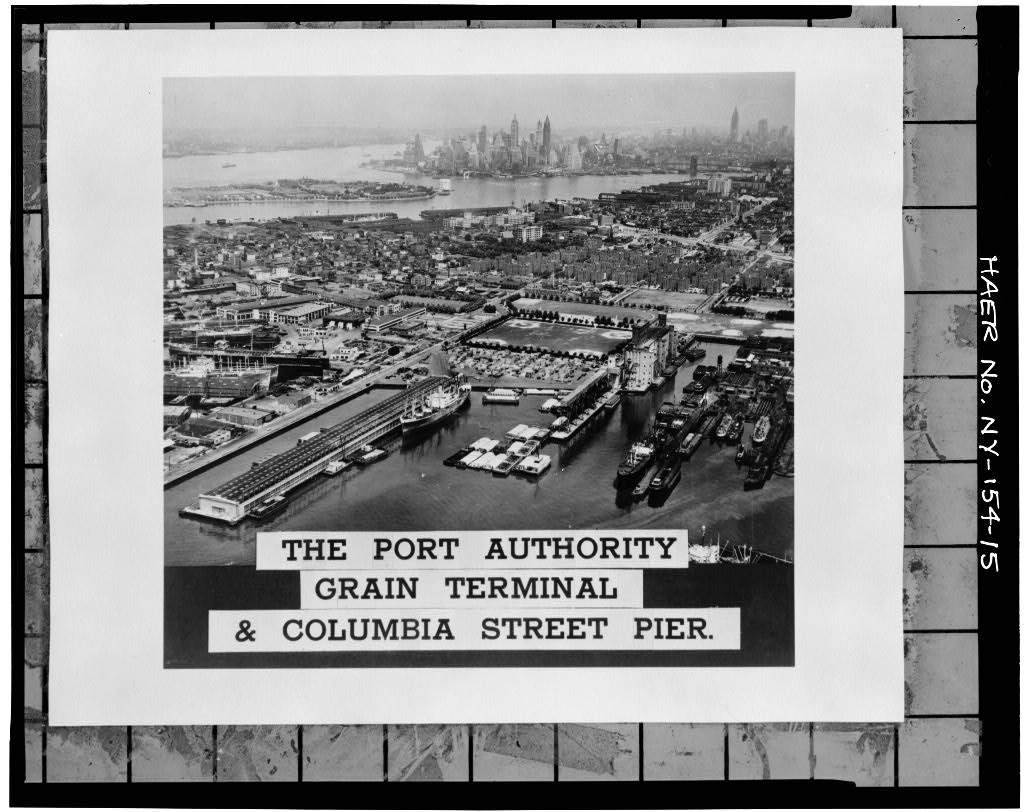

The Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard was located on the north side of Gowanus Inlet, Brooklyn, just east of the New York State Grain Terminal, at the south end of Columbia Street. The company was established in 1907, and operated until its final closure in July of 1981.

“New York Barge Canal, Gowanus Bay Terminal Pier, East of bulkhead supporting Columbia Street, Brooklyn, Kings County, NY.” June 25, 1950. Historic American Engineering Record, photograph by Flagg, Thomas R., retrieved from the Library of Congress.

The Bushey family emigrated from Quebec, Canada, in the late 1800’s, and settled in Oswego, New York. Ira S. Bushey, much like the young Irish immigrant Michael Moran, who founded the Moran Towing Company in 1860, drove mules on the Erie Canal in the latter half of the 1800s. Mr. Bushey migrated west for a number of years, returning east and settling in Jersey City in 1895 where he started a boat repair business. He then moved first to Staten Island in the 1900s, and about five years later settled in Brooklyn. In 1903, when Mr. Bushey’s oldest son was 15, he incorporated his business as Ira Bushey & Sons, and in 1907 Bushey acquired the Downing & Lawrence Shipyard on Court Street on the Gowanus Creek. The business continued to grow for the next seven decades.

The shipyard focused on making barges, railroad flats and scows (a type of flat bottomed barge), and by 1919 they had built and launched 254 of them. A year later Ira Bushey & Sons completed a 15,000 ton dry‐dock on their Red Hook property that was able to lift a ship in just 18 minutes.

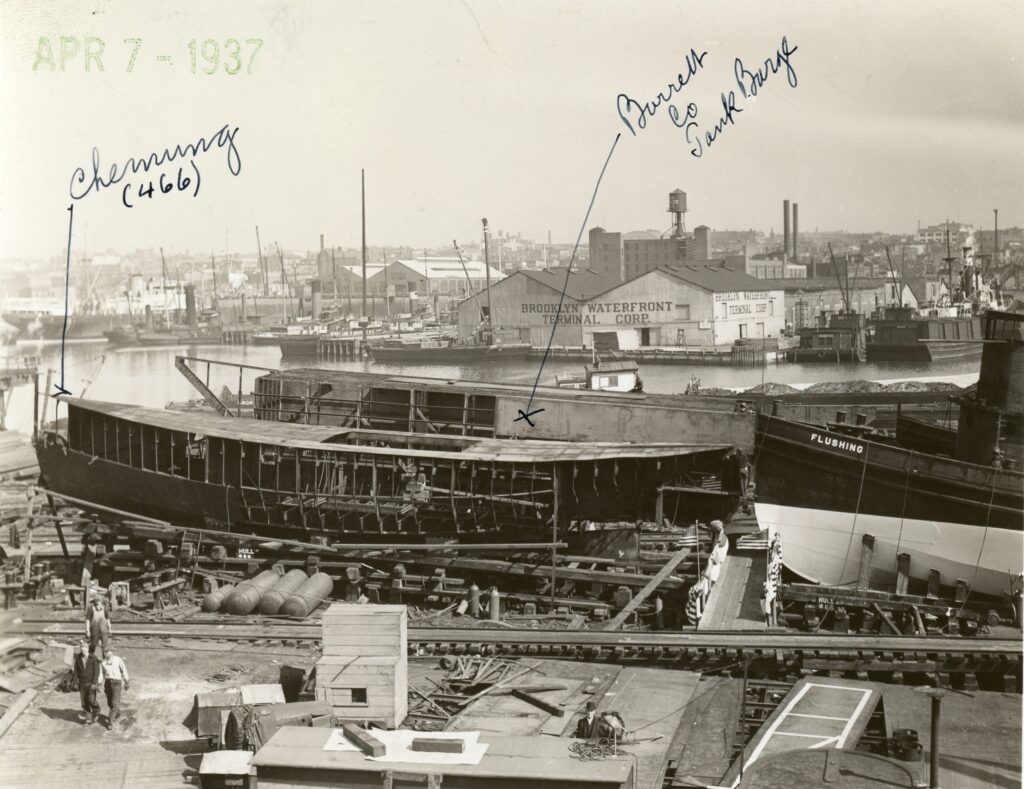

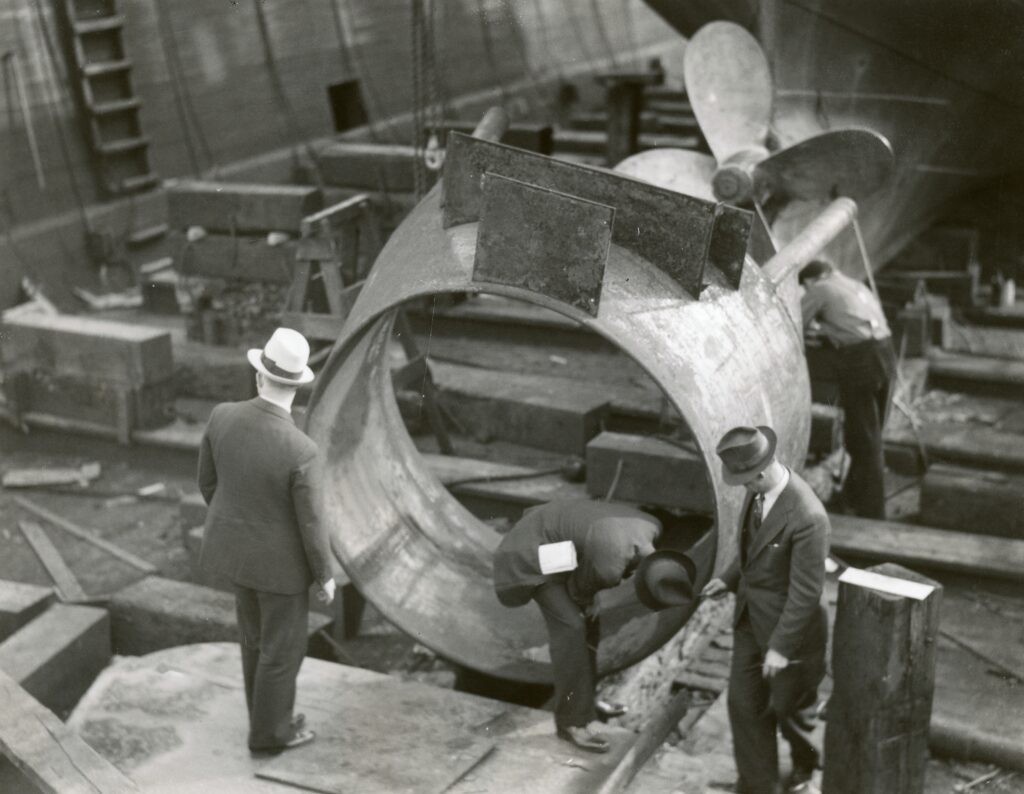

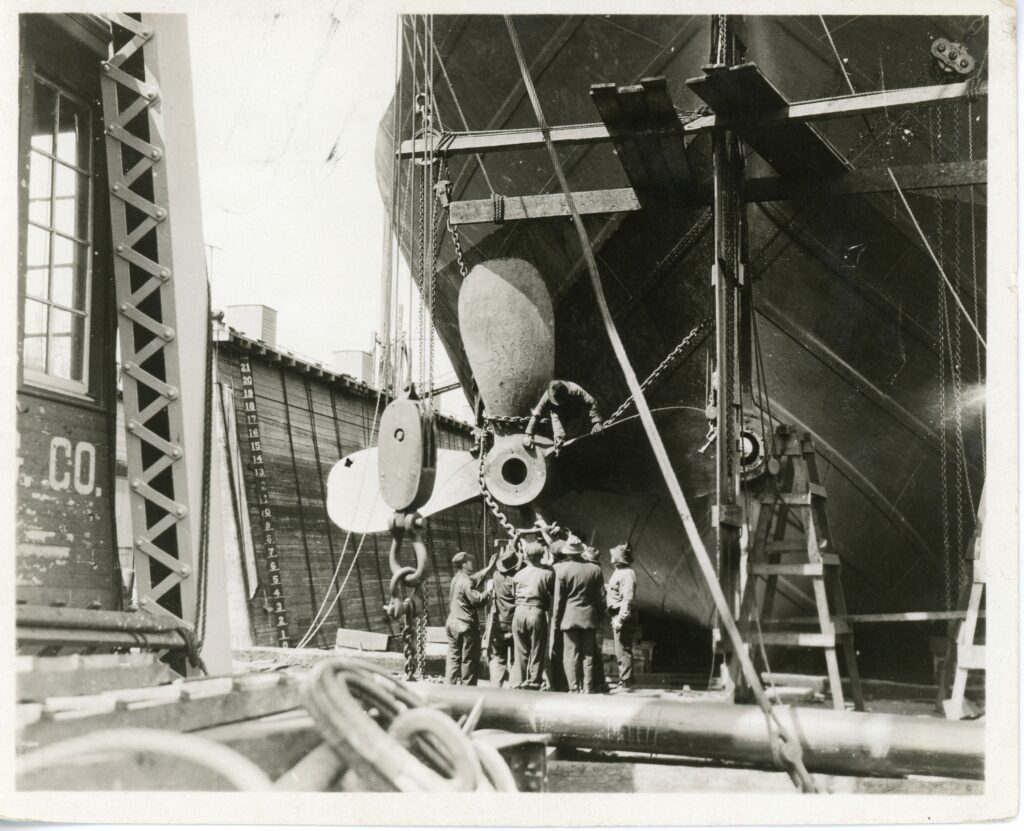

Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard, April 7, 1937. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive H33-0062

Small vessels were built on land in the yard during both wartime and peacetime. The company entered into the transportation business in 1924, forming a barge company called Brooklyn and Buffalo Navigation Company (B&B) which moved cargo down the Erie Canal from Buffalo to Brooklyn. A year later, in 1925, Mr. Bushey formed another company, diversifying again his business due to the growing popularity of cars, and the demand for gasoline. The Spentonbush Fuel Transport Service was a shipping company, which derived from the names of the three founding partners, Spencer, Toner, and Bushey. Ira S. Bushey died on September 25, 1925, and his four children were left to carry on the business empire.

In 1940, Bushey bought the Todd Shipyard on Clinton Street, Red Hook, Brooklyn, and transferred all shipbuilding facilities to this location, where, during World War II, they built small vessels for the US Navy, Coast Guard, and Army.

Ira S. Bushey & Sons also owned and operated a small fleet of coastal tankers, both built by themselves and built in other yards. One tanker they owned, the Mary A. Whalen, built at Camden, New Jersey in 1938, is now preserved in Red Hook, Brooklyn.

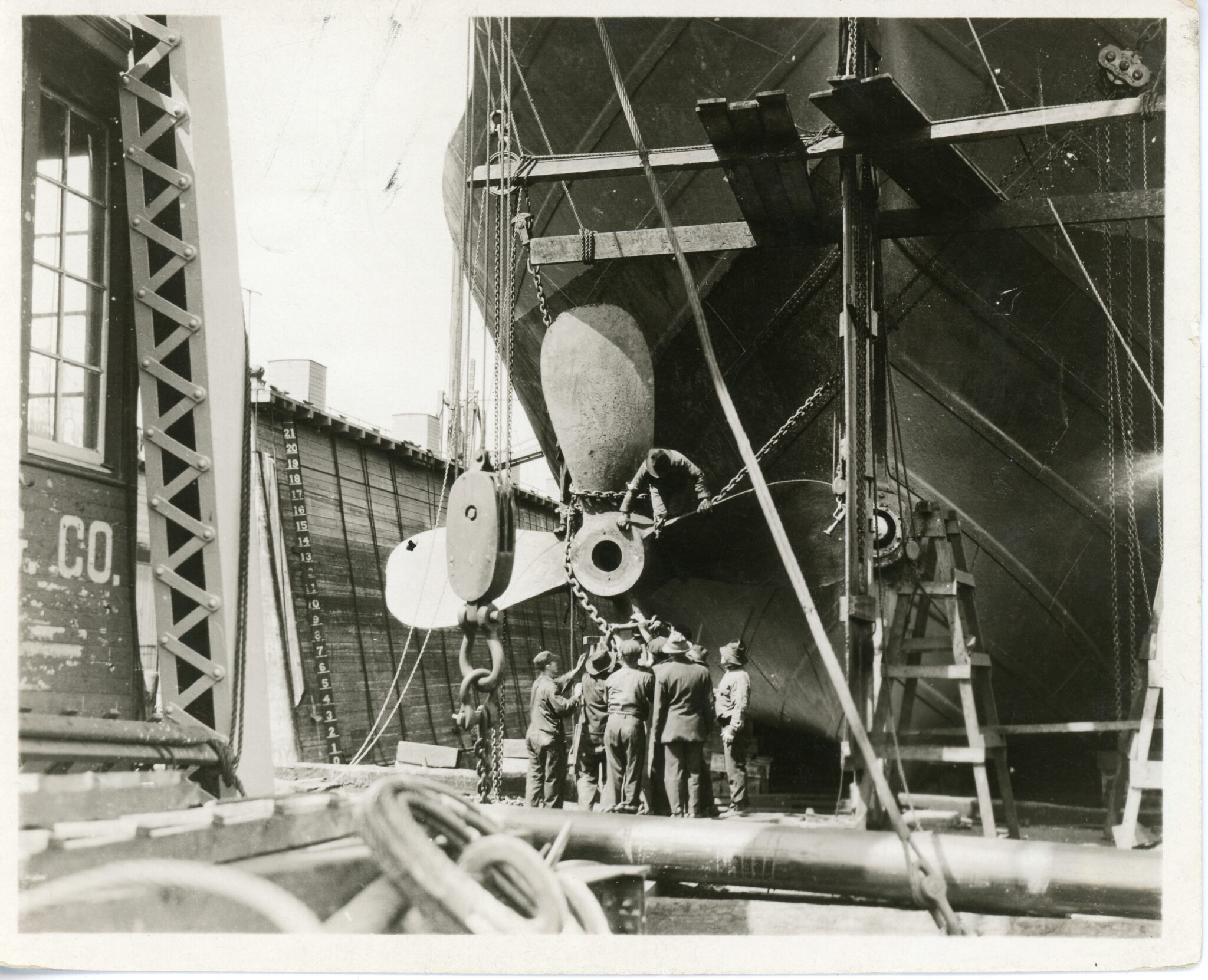

Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard, ca. 1950. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive H33-0036M

In 1966 Ira Bushey & Sons built their last vessel, the tug Boston which, unlike earlier ships, had an automated engine room, requiring only one engineer to be assigned to the vessel instead of three. If you are interested in seeing all of the vessels that came out of the yard this is a pretty comprehensive list.

From 1966 until the yard closed in July of 1981 they kept working to repair vessels. A last point of interest happened in 1968 with the court case “Ira Bushey vs. USA” where the US Government was held liable for the conduct of a drunken sailor in the Bushey’s shipyard. The case is related to a crewmember on board the United States Coast Guard cutter Tamaroa, who was drunk and opened the tank valves which caused the ship to fall and destroy parts of the Bushey’s drydock. The US Government appealed claiming they were not liable as the crewmember’s acts were not within the scope of his employment, but the reviewing court affirmed. The United States Court of Appeals ruled that the seaman was a government employee and thus the government was liable for his actions. This case is often taught in law schools today.

Now, can you understand why I am fascinated by this history and the related collection of material culture and historic records? This is a quintessential American immigrant history, a family enterprise with many successes and developments due to the industry, workers, and the country’s needs, in the heart of New York City.

For seven decades Bushey repaired and built ships on Court Street, building more than 600 vessels, and the Seaport Museum’s collections and archives hold a variety of artifacts, tools, ship plans, and photographs of the shipyard’s activities, vessels, and workers.

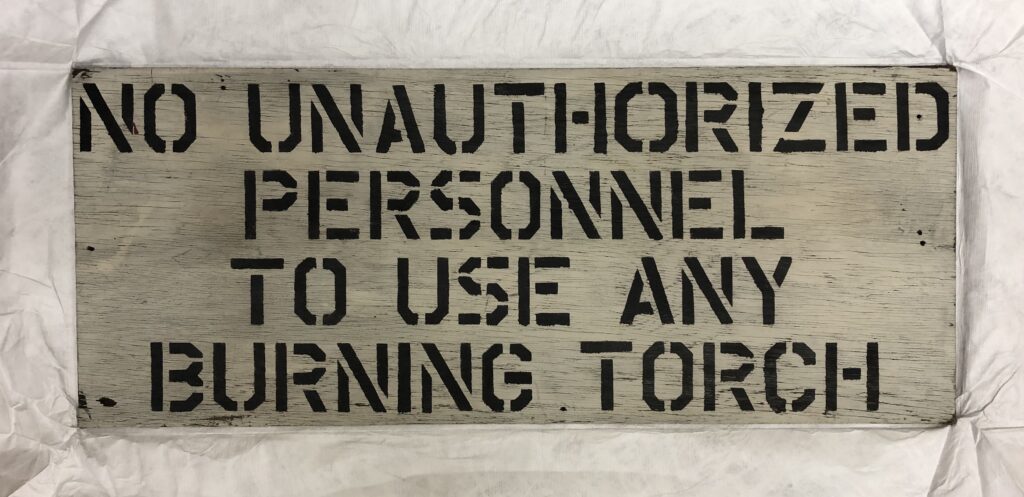

The Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard Collection arrived at the Museum in the summer of 1981. The Museum’s Historian at the time, Mr. Norman Brower, recorded the following: “I learned the yard was going to be closed in June 1981. I went there to photograph the yard and see what might be available for the museum collection. I was given a box of snapshots and negatives of the yard, most dating from World War II, but some earlier. I was also given two file drawers of folded plans of vessels they built or altered. I was also able to remove blackboards where jobs had been listed, and name boards over the doors of various workshops, which I thought would be useful in future exhibits on New York shipyards.“

Sign from the Ira S. Bushey Shipyard, mid 20th-century. South Street Seaport Museum 1981.020.0043

Left: Pattern for a porthole, mid-20th century. South Street Seaport Museum 1981.020.0015

Right: Pattern for hawsepipe, mid-20th century. South Street Seaport Museum 1981.20.0017

After the Museum took possession of these items, and the Collections Committee voted for their acquisition approval, the Registrar[1]A registrar is a person responsible for the care, security, record keeping, and transportation of collection belonging to cultural institutions. Typically works in museum or similar settings. … Continue reading prepared a Deed of Gift and Thank You Letter. These essential documents, countersigned in September of 1981, provide a lasting record of the transaction. After these official steps came “the fun part”; the fascinating and meaningful ongoing care and preservation, cataloging, research, and documentation of the new assets.

The purpose of a modern museum is to collect, preserve, interpret, and display items of cultural, artistic, or scientific significance for the education of the public both today and in the future. Museums wouldn’t be museums without their collections of artifacts and historic records, but it can be a challenge to make sure those items are around for generations to come; after all entropy is inevitable. We, collections managers, registrars, and archivists, need to navigate a delicate balance between care and preservation, use and display, budgeting, ethical boundaries and laws’ application. Collection management is ongoing, and collections documentation often takes years to be completed, not including the needs of recurrent updates based on the discovery of new original sources and historic records; additional knowledge often appearing from relatives, donors, and researchers, and conservation.

In the case of the Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard Collection, today, 39 years after we took possession of it, we have quite a few opportunities still undergoing.

Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard, ca. 1950. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive H33-0014C

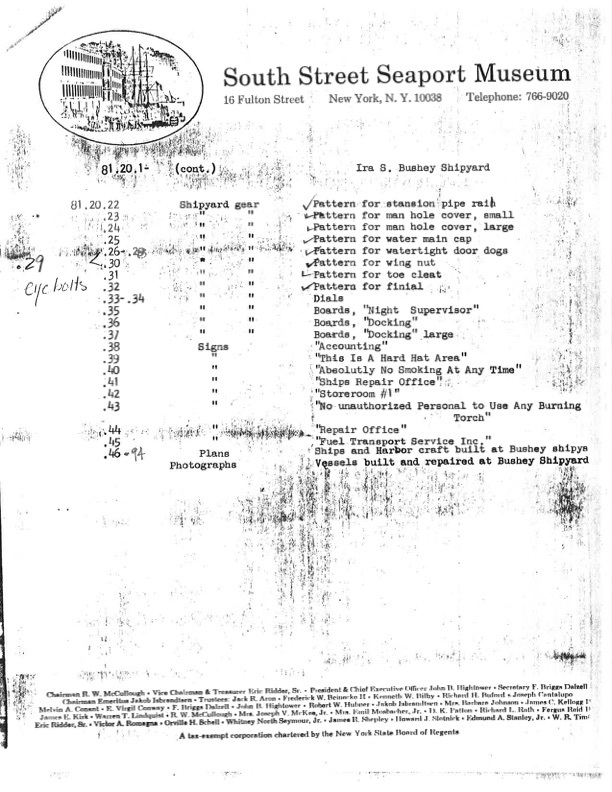

As mentioned earlier, the documentation of this donation consists of a Deed of Gift, and a Thank You Letter. The deed documents 46 items, with the 46th listing “ship plans and photographs” without an item count, or a distinction between technical drawings, photographic prints, and negatives. Additionally we have an additional handwritten annotation, undated, which crosses over the number 46 with number 94, adding to “ship plans and photographs” another 47 items.

Now, we have more than 47 individual ship plans, and this number does not include the amount of photographs tied to the Bushey shipyard in our archives. So, what should we do next?

This might seem to many just a mathematical or tedious exercise, but it’s actually the basics of initial custody and documentation of taking possession of an object, or a collection of items. “Keeping object entry under control relates directly to museum mission and collection management policies. The process that emerges from these documents can strengthen a museum’s ability to decrease risks associated with abandoned property, old loans, partially processed objects, and the objects that eventually become found-in-collection objects.”[2] “Initial Custody and Documentation” by Rebecca Buck, published in Registration Method, 5th Edition, by the AAM Press, pp. 38-43.

As of February 2020, after much research, inventory, and digging in our archives, we have on record over 394 items tied to this donation, including the first 45 items, and 349 folded ship plans recently catalogued and rehoused in three new acid-free boxes.

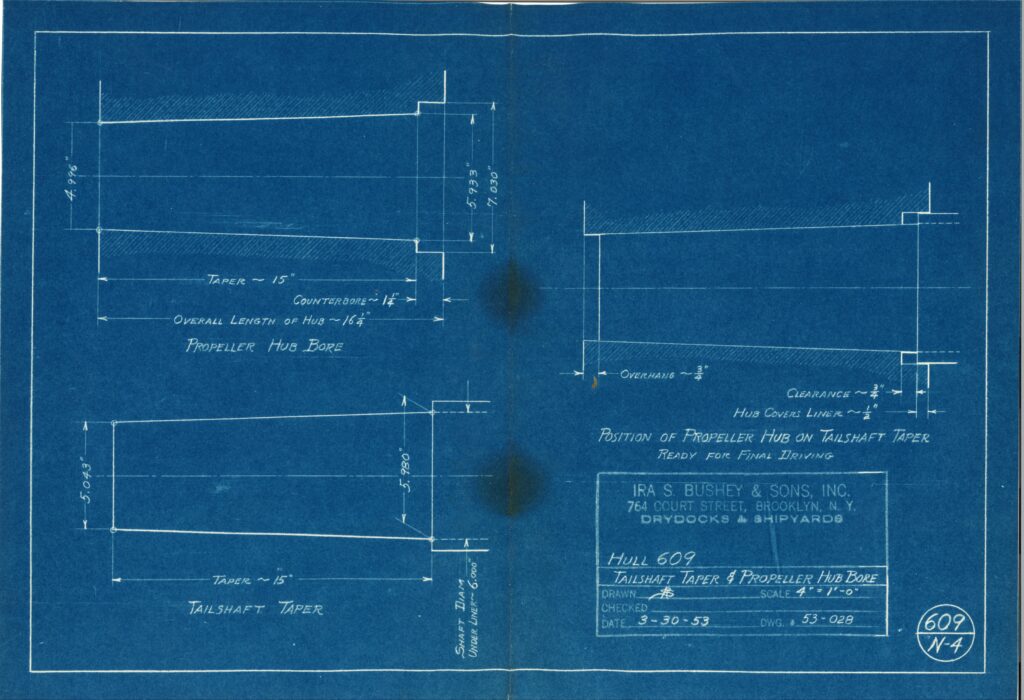

Blueprint for Hull 609, Tug Keegan. Tailshaft Taper and Propeller Hub Bore. March 30, 1953. South Street Seaport Museum 1981.020.0096.A-B

These technical drawings were catalogued and described at a level we call “good enough,” to be able to be tracked in our database, to do internal research as well as to aid research requests coming our way. Since 2015, we have received quite a few of these inquiries, and while we were trying to honor these requests, we really needed to have a more detailed item inventory in our database. Until recent months this proved to be nearly impossible as the plans did not have individual accession numbers on them and there was little to no description of the plans on file.

Lastly, by doing this quick inventory we found some plans had extensive damage caused by the rust of paper clips and staples in between papers, files, and plans. As we assigned accession numbers, we also removed these metal devices, and rehoused files in new acid-free folders and acid-free boxes.

The artifacts, which were already pretty much accounted for, hadn’t been complete photographed and condition reported since in the early 1990s, so we did a full new imaging session, together with condition reports and additional detailed documentation. We researched and recorded new information on workers regulations and facilities’ rules, as well as inscriptions found on other types of artifacts that could lead us to connect these objects to ship plans or photographs.

Pattern for tail shaft nut, early 20th century. Gift of Jonathan R. Bushey, Ira S. Bushey Shipyard 1981.020.0018

Lastly, in the case of the photographs, the cataloging is still a bit of a work in progress. As of November 2019, no inventory of the photographs that arrived with the donation has been found. The photographs were split into different parts of the Museum’s Maritime Reference Library (once held in Thomson & Co. at 213 Water Street, 2nd Floor) including a few different photo archives and subject files, and their provenance[3]Provenance is the documented history of ownership and location of an object. Provenience is an archaeological term meaning the three-dimensional context (including georgraphical location) of an … Continue reading was not tracked.

Though there was no explicit summary of the organization of the Museum’s photo archive at the time of the Bushey donation in 1981, a 1987 survey describes the photo archive at that time. Photographic prints and negatives were separated, and photographic prints were divided by subjects including “Local History”, “Buildings” and “Ships”. The survey notes that the photos in these categories were arranged alphabetically instead of by collection/donation, meaning that the provenance of the photographs was not tracked. The 1987 survey mentions the Bushey collection specifically as an example of poor provenance tracking, since the collection’s negatives were “scattered within” the larger negative collections.

Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard, ca. 1940. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive H33-0041A

In 1997 there was an attempt to catalog the photo archive to better track the growing number of photographs. Though there is a file of documents and proposed schemes, it does not appear that the plan was implemented.

Additional opportunities came to play with other photo archive catalog systems implemented over the past 30 years or so, but all of these systems are in slight conflict with one another.

Processing the photographs that were donated in 1981 as part of that accession is difficult because we cannot be sure which photographs were part of the original donation, and which photographs were collected at a later date.

Ira S. Bushey & Sons Shipyard, ca. 1940s. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive H33-0004B

The Bushey donation is only one case of many in the Museum’s collecting history of photographs being donated with accessioned objects, separated and sent to the Library and divided into different archives with no tracking, then partially processed over time in different systems. For many photographs we can only guess if they arrived with an accession and we will use our best guess to assign numbers in that accession based on incomplete information.

All of these opportunities are tied to the development and fast evolution of library science and collection management, their related computerization and the addition of modern technology to the management of both archives and material culture. As John Lindaman, Manager of Technical Services, Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently said in the Library’s newest episode of “In Circulation” blog “There’s a popular misconception that librarians as a profession are conservative. Not politically conservative, but literally conservative—wanting to keep old stuff. Actually, nothing could be further from the truth—we are often on the cutting edge of using new technologies, and always looking for the most efficient, up-to-date way to help our patrons.”

In our case, the ongoing desire to get our collections online for the public goes hand in hand with knowing what we have and our items’ locations, conditions, and related information. This seemingly tedious process of wall-to-wall inventory is a step in the right direction to help with that, and we can’t wait to share with all of you more of our holdings!

Additional Readings

Low Bridges and High Water on the New York State Barge Canal, by Charles T. O’Malley, published by North Country Books, Inc., 1991.

Tug O’ the Heart by Marian Betancourt, published in Irish America, February-March 2003.

Things Great and Small: Collections Management Policies, by John E. Simmons, published by the American Association of Museums, 2006.

Tugboat and Shipyards: The Russels of New York Harbor, 1844-1962, by Hillary Russell, Jr., published by Hilary Russell, 2019.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | A registrar is a person responsible for the care, security, record keeping, and transportation of collection belonging to cultural institutions. Typically works in museum or similar settings. Registrar is not be confused with record keepers who work for government or business entities; and definitely not as a n office at college of university. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Initial Custody and Documentation” by Rebecca Buck, published in Registration Method, 5th Edition, by the AAM Press, pp. 38-43. |

| ↑3 | Provenance is the documented history of ownership and location of an object. Provenience is an archaeological term meaning the three-dimensional context (including georgraphical location) of an archaeological find, giving information about its function and date. The work of provenance research and its documentation requires the support of an entire institution, with the goal of making provenance information accurate, consistent, and available to researchers and the general public. Museum Registration Methods, 5th Edition, p. 66-76. |