Learn about an important navigation instrument and its “Little House”

A Seaport Museum Blog

by Malcolm Martin, Fleet Captain

May 13, 2021

The ship’s magnetic compass has been around in various forms for more than a millennium. Navigators all over the world discovered the properties of magnetic compasses.[1] Peter Kemp, “The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea,” 1976

Since their development, ships carry compasses to help navigate when conditions required a reference aboard the ship to provide orientation. At night, or otherwise out of sight of familiar landmarks, a compass provides vital information for the navigator.

The compass on ships is often mounted in a binnacle which is a stand or housing. Its delightful name Binnacle derives from Latin habitaculum meaning “little dwelling place”.

This “little house” helps to protect the delicate compass from the elements. They usually contain a gimbal arrangement to hold the compass card horizontal despite the motion of the ship. In addition the binnacle usually contains a light of some sort to illuminate the compass face to facilitate reading it in the dark and shades to make reading it in sunlight easier. Binnacles are typically made of wood or brass or other non-ferrous metals. They are located in a place on the ship to allow the ship’s navigator to determine position and course. They may be located near the helm so that the sailor steering the ship can maintain the correct course.

Left: This particularly beautiful binnacle in the Seaport Museum’s collection was made by John Bliss and Co. which had offices in the seaport district from 1857-1957. (Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 1991.072.0141)

Right: Commonly, as part of the binnacle, there are adjusting magnets, flinders bars, and often external iron spheres which allow for adjustment of the compass. The iron adjusting balls attached on each side of the binnacle, as we can see in the above Seaport Museum’s Kelvin and Hughes Binnacle. (South Street Seaport Museum Collection 1979.004)

But why would the compass need adjustment, it is always supposed to point North, right? The reason is that as a critical piece of navigational equipment the accuracy of a ship’s compass can literally mean the difference between life and death for a ship and her crew. The compass’ accuracy must be maintained at the highest possible precision while at sea.

The compass contains a magnet (or magnets) that orient predictably to the magnetic field of the earth. In an ideal situation the compass would respond only to the earth’s magnetic field and would indeed always point to the Magnetic North Pole. In reality however, the compass magnet responds to the local magnetic field around it. That local field is a combination of the earth’s field modified by nearby magnetic influences. Anything containing iron— everything from ballast stones with high iron content to ferrous (iron containing) metals such as nails and other fasteners, rigging, electrical equipment, engines and other machinery and of course iron and steel hulls— distort the local magnetic field around a compass. Ships with hulls made of iron or steel have very significant local distortion but even wooden (or fiberglass) vessels contain sufficient ferrous metals to influence the local magnetic field around the compass.

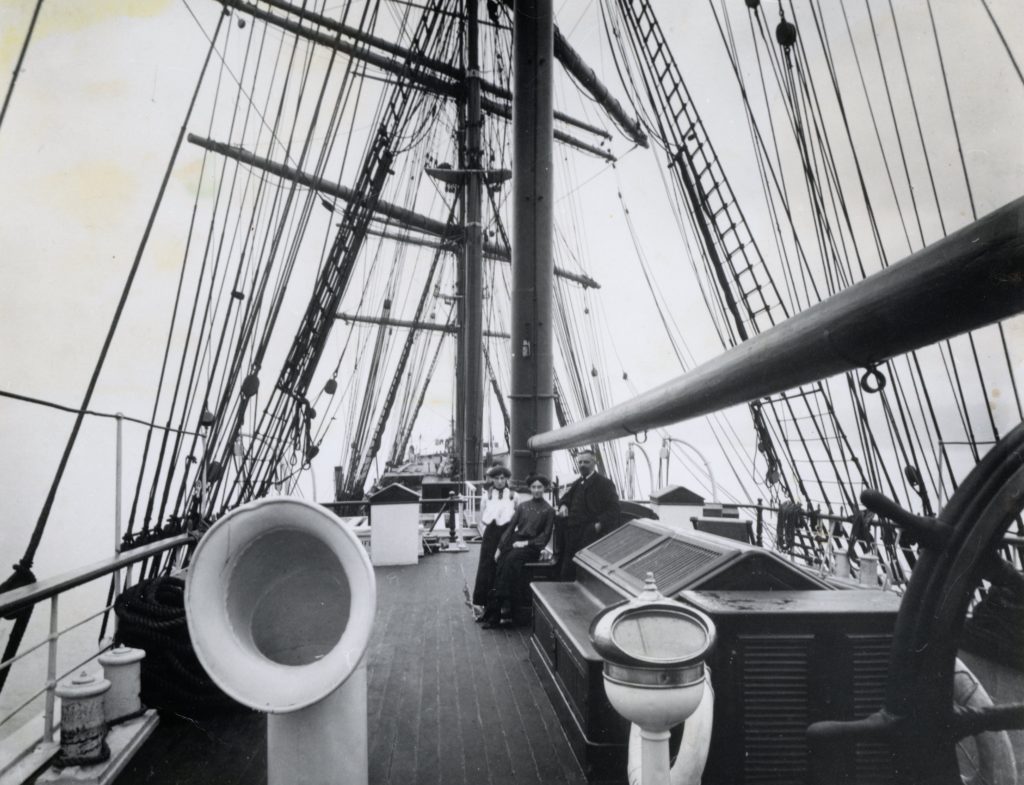

You will notice that on Wavertree the binnacle is located on a platform up over the deck and away from other structures. This is in an attempt to minimize the effects of the magnetic properties of the iron ship and to place the compass close to the magnetic center of the ship.

The binnacle located on the catwalk of the 1885 cargo ship Wavertree

In fact, it is common for the standard compass to be mounted away from the helm position even on modern vessels. Also note that in addition to her main compass which was remote from the helm, Wavertree was equipped with two steering compasses located by the helm on the quarterdeck. These would be the references the helmsman would use to steer a steady course.

Left: This image shows one of a pair of steering binnacles by the wheel on Wavertree’s sister ship, the Leicester. (South Street Seaport Museum Archives)

In fact there may also be other compasses aboard a ship such as a “Tell-Tale Compass” in the Captain’s quarters by which the Master could see the course being steered without going on deck. Some larger ships are required to carry a spare compass in addition to thor standard compass to this day.

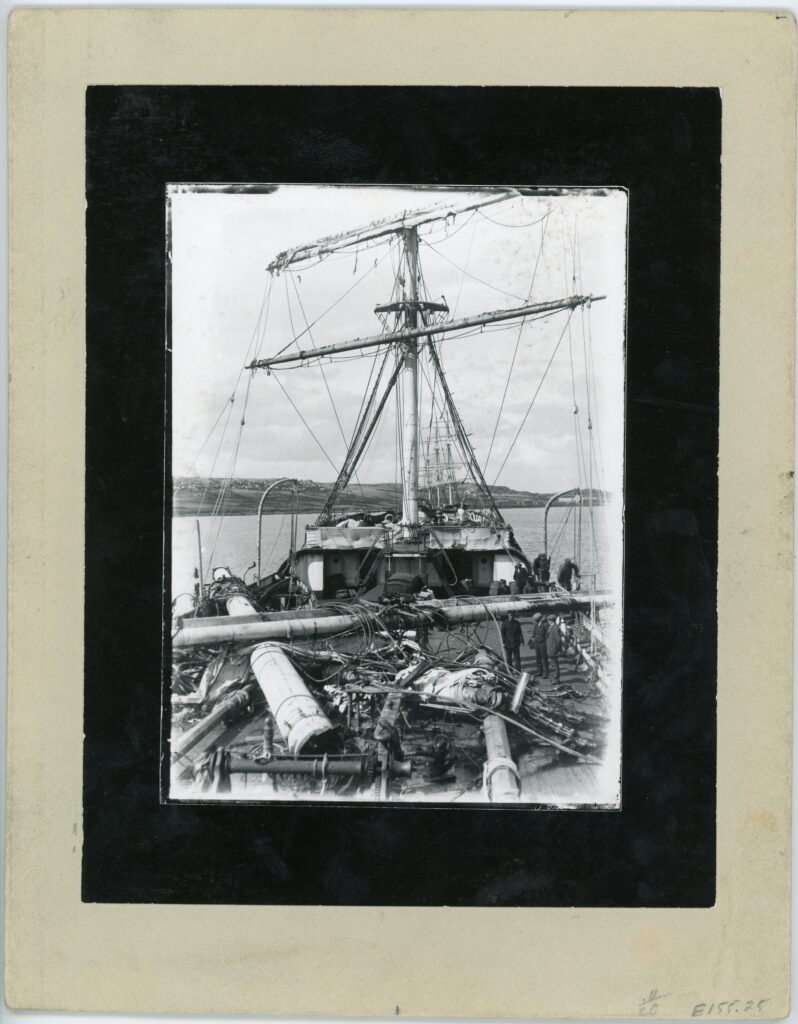

In this picture you can see that the Wavertree’s dismasting off Cape Horn carried away the binnacle containing the standard compass along with the boat skids. Lucky for her crew, they had the steering compasses aft still intact! (“Wavertree dismasted, looking aft” n.d., original ca. 1910-1911. Gift of Joe King and Stanley Senior School Photography Club, Falkland Islands, South Street Seaport Museum 2018.002.0002)

Anyway back to compass corrections. Whatever the cause, the local distortion of the earth’s magnetic field makes the compass inaccurate for use in navigation. As stated above, much depends on the accuracy of the ship’s compass. Luckily, at least some of the distortions caused by the structure and gear of the ship remain fairly constant so it is possible to correct the errors by using small adjuster magnets, iron rods and compensating balls. These are often incorporated into the binnacle. The arrangement of the latter iron spheres was developed by William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) in Scotland.[2] To read about Lord Kelvin’s accomplishments see “Lord Kelvin, G.C.V.O.” by John Munro, London, 1902. Collectively, these devices also distort the local magnetic field around the compass but are arranged to distort the readings of the compass back to correct!

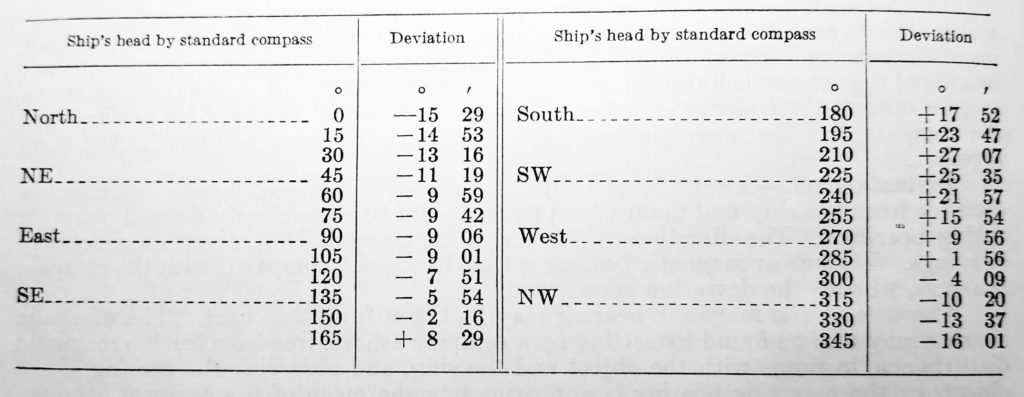

A professional Compass Adjuster is a person who corrects the compass as best as possible using the compensating devices in a process called swinging the compass. The compass errors vary depending on which way the boat is pointed (the Heading of the ship), so it is a fairly involved process to measure the error and adjust the compass to read correctly no matter what the ship’s heading is. Even after the best adjustments, there are still residual errors. These errors are collectively called Compass Deviation. The Compass Adjuster creates what is called a “Deviation Card” for the compass which shows the known compass errors for all headings of the ship. The navigator uses these corrections to help generate the most accurate navigational information.

Above: Compass Deviation Card from American Practical Navigator, Nathaniel Bowditch

A new ship or one that has been significantly repaired or modified would have its compass swung by an adjuster upon launching. International maritime treaty regulations require that all ships carry a compass that has been swung at least every two years.[3] Requirements and Guidance for Magnetic Compasses according to Chapter V, Regulation 19 of the Safety Of Lives At Sea (SOLAS) Convention under the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). Even so, it is a regular part of the “Day’s work” for the Ship’s Navigator to check the accuracy of the compass by piloting methods if close to land and methods of celestial observation while at sea.[4] Nathaniel Bowditch, “American Practical Navigator, HO No. 9,” 1947. This regular check ensures that the accuracy of the compass has not been lost inadvertently and unnoticed by some event which has altered the local magnetic field of the ship or the adjusters. If errors are found they would be noted and used to correct compass bearings. If gross errors (as might be expected after a lightning strike or physical damage to the binnacle) are discovered then the navigator would need to be prepared to make compass adjustments at any time during a voyage.

Even to this day with all the modern electronic and satellite instrumentation ships carry, the “little house” and the compass within remain a critical piece of equipment. They are a refined and delicate navigation instrument. This ancient tool is still carried and maintained to provide critical navigational information should other systems fail.

References

| ↑1 | Peter Kemp, “The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea,” 1976 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | To read about Lord Kelvin’s accomplishments see “Lord Kelvin, G.C.V.O.” by John Munro, London, 1902. |

| ↑3 | Requirements and Guidance for Magnetic Compasses according to Chapter V, Regulation 19 of the Safety Of Lives At Sea (SOLAS) Convention under the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). |

| ↑4 | Nathaniel Bowditch, “American Practical Navigator, HO No. 9,” 1947. |