Architectural elements collected by Joseph Mitchell

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

September 30, 2021

The Seaport Museum began collecting architectural elements in its early days thanks to a critical figure in the history of New York City’s historic preservation movement, who is actually more well known for his writing: author Joseph Mitchell (1908-1996).

The Museum’s collection of architectural elements and building components includes bricks, doors and windows, samples of wallpaper, cast iron and terracotta ornaments, structural ironworks, and more. The objects are examples of the changing physical fabric of New York City, and particularly of its waterfront, Lower Manhattan, and the South Street Seaport Historic District. A good portion of our artifacts belong to different adaptations and style iterations of Schermerhorn Row, a block of Federal-style counting houses built between 1810-1812, and home of the Seaport Museum since the 1970s. But we also hold remnants and ornaments from other significant buildings, including many that are no longer extant, such as the 1882 Fulton Market building, the Edgar H. Laing Stores, and the Rhinelander Sugar House Building, among others.

Over the past few months I did more in-depth research into these historic features as the Collections Department is about to release new galleries on our Collections Online Portal including highlights of this remarkable collection. While reviewing the inventory work that has been done in the past by interns and staff I realized that most of our artifacts that have incomplete or missing provenance paperwork were actually collected and donated by Mr. Mitchell, and his good friend, fish market businessman, and one of the founding fathers of the Seaport Museum Joseph Anthony Cantalupo (1906-1979)[1]”Joseph Canatalupo, 73; Helped Seaport Museum” New York Times, August 8, 1979. After scouring our own institutional archive and collections management paperwork, I went to research Mr. Mitchell’s papers at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations, with the hope of shining more light on the connections between the famous author and the Museum.

The Joseph Mitchell papers are described as “primarily related to Mitchell’s career as a journalist and New Yorker writer and his proclivity to document life in New York City.” The collection is composed of 127 boxes, 4 volumes, 2 oversized folders, and 504 computer files, including correspondence, writings, research material, notes, ephemera, and photographs. A good portion of it is dedicated to his time spent at the Seaport from the late 1960s through the mid-1980s—meeting with friends, reporting his errands and discoveries, researching the Fulton Fish Market and Fishmonger Association, volunteering for the newly created Seaport Museum’s Local History Committee and (later on) the Museum’s board and the board of the New York City’s Landmark Historic Commission.

The three days I spent at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library filled me with joy, surprise, and an incredible nostalgia for the New York City of the 1960s-1980s. It was a time when the city and our beloved neighborhood were full of energy, excitement, as well as concern for the city’s progress and changes. In some ways it appears not much different than today, but with a fascination of the past and civic pride.

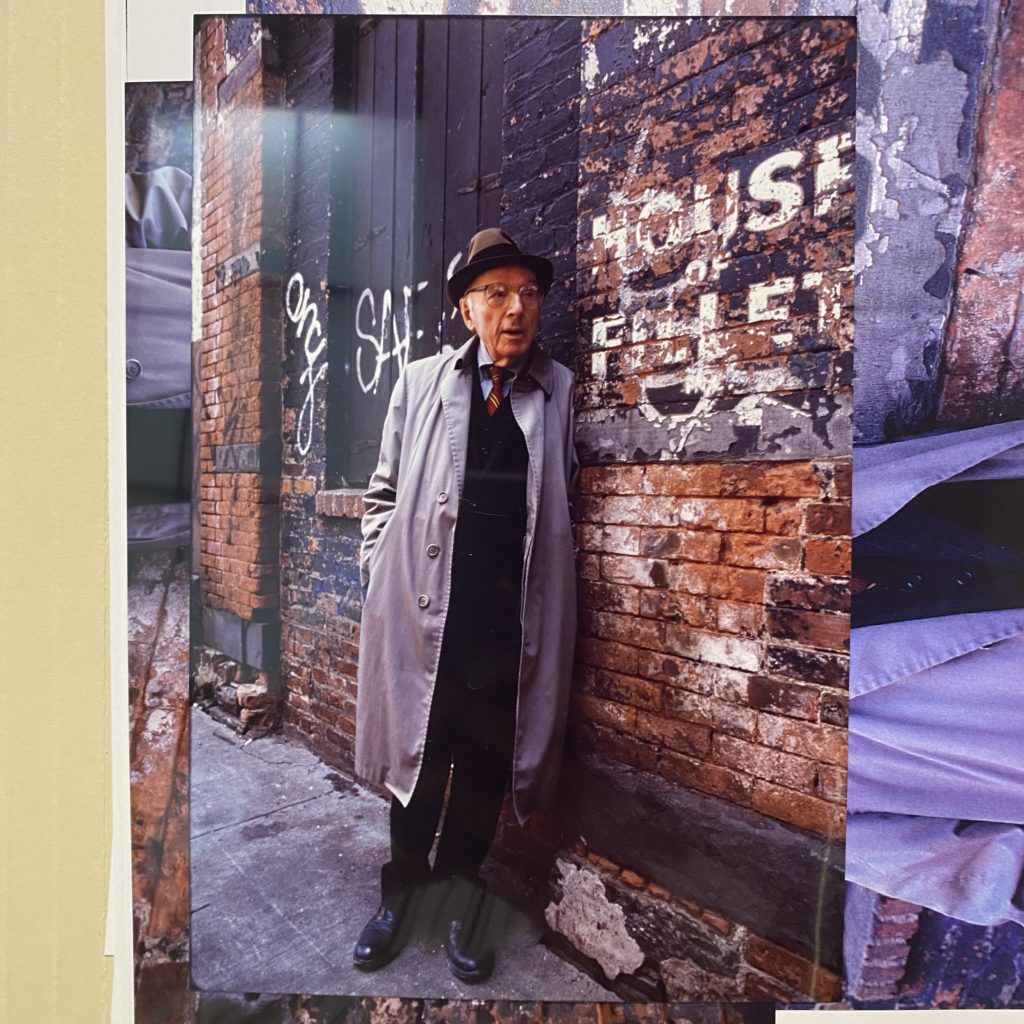

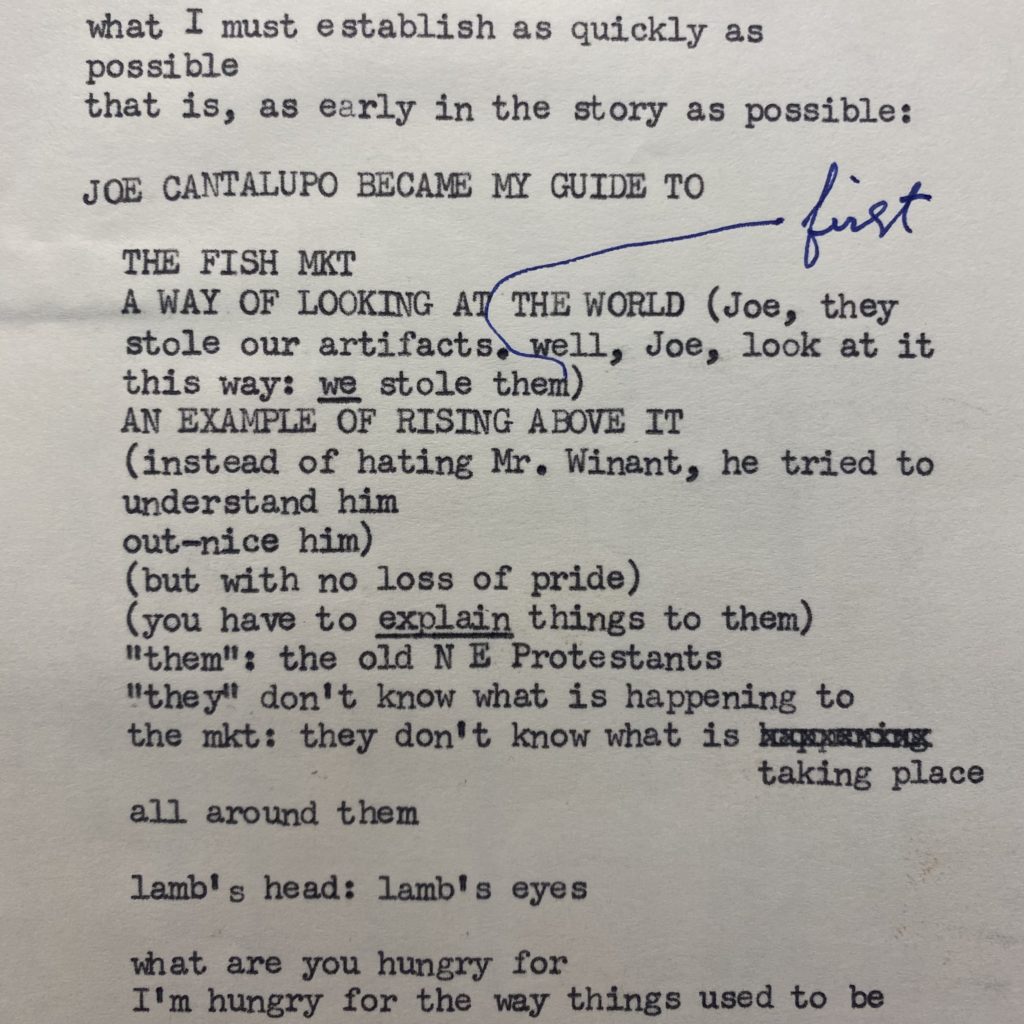

Miscellaneous materials from the Joseph Mitchell papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Left image from Box 33. Right image from Box 72, Folder 72.7. Researched on September 7 and 8, 2021.

From the earliest days of the Seaport as a historic district, both Mitchell and Cantalupo were well aware “of the dangers involved in the process now known as gentrification.”[2]Joseph Mitchell papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Box 72, Folder 72.1 – Cantalupo, Joe and Bob 1970s-1980s. Many recollections and notes between the two involved detailed stories of the Fulton Fish Market and District-related business operations, mixed with personal connections, family history, and stories of remarkable people of the area including renowned fishmongers, business men and women, restaurateurs, and early Museum staff and volunteers.

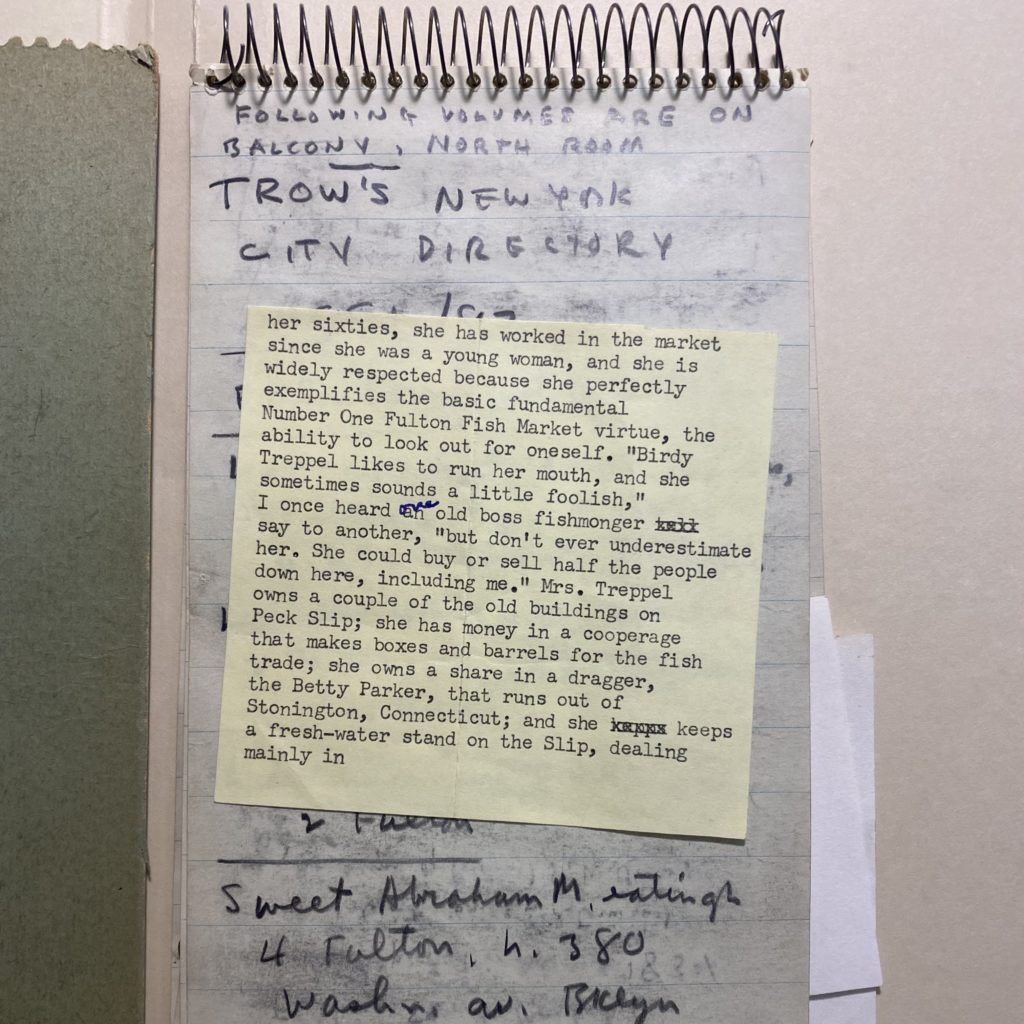

Miscellaneous materials from the Joseph Mitchell papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Left image from Box 72, Folder 72.1. Right image from Box 102, Folder 102.3. Researched on September 8, 2021.

Mitchell was meticulous in his records. The papers I looked at include boxes upon boxes of handwritten and typed notes on his daily errands from coming to the South Street to meet with Mr. Cantalupo, and having lunch at Sloppy Louie’s (at 92 South Street) to catch up with Norma and Peter Stanford, along with Annie and Ted Stanely—all early founders of the Museum. He noted how often he took cabs to run some errands and to visit other areas of Manhattan and Brooklyn, where he would meet people, attend meetings, or check on other historically important buildings and neighborhoods.

I found enough materials to “write a book” about his passion for cast iron architecture, brick making, and general historic preservation, and there is still so much to uncover, but for now, allow me to bring you on a brief virtual stroll from Tribeca to Hoboken, and learn about a few lost structures that live on in the Seaport Museum collections thanks to Mr. Mitchell.

New Yorkers walking in today’s Tribeca neighborhood appreciate the area’s restaurants, cafes, shops and art galleries, and can look upwards to see One World Trade Center rising overhead; however, they are probably unaware that an enormous food hub called Washington Market used to make its home there.

The neighborhood market started in 1812, and operated until it was forced to relocate to Hunts Point, in the Bronx, in 1962, due to a large upcoming urban renewal project, including the site that was to become the World Trade Center (similar relocations of City markets happened to the Gansevoort Market Meat Center in Chelsea, and later the Fulton Fish Market in the South Street Seaport Historic District.)

The Washington Street Market was one of several markets all over Manhattan, delivering fresh produce and dairy to city residents. It began at a small neighborhood scale, but it eventually grew to encompass several city blocks—almost like a city within a city, including a related ecosystem of services and infrastructures.

“The New West Washington Market, New York City” 1888, Wood engraving on paper. The Clark Art Institute, 1955.4303.

David O’Neil, Projects for Public Spaces’s public market expert, describes, “It started outdoors, then moved indoors, and then grew enormously over the years to include retail, wholesale, cold storage space, commission houses and brokers. When markets grow, you get to a certain scale of operations that gets other people providing supplies such as ice, lights, and hardware. There is a lot of evolution within the market and adjacent to it.”[3] “How Markets Grow: Learning From Manhattan’s Lost Food Hub” by Patra Jongjitirat, November 24, 2012.

Roughly half of the Washington Street Urban Renewal Area slated for demolition was of occupied land, containing nine Federal-style townhouses utilized by hotels, stores and warehouses—two of them by John McComb (1763 – 1853), one of the architects of City Hall—and five sections of the Laing Stores, known as the Bogardus Building.

Mitchell recorded he was specifically interested in some of these buildings (all getting demolished.)

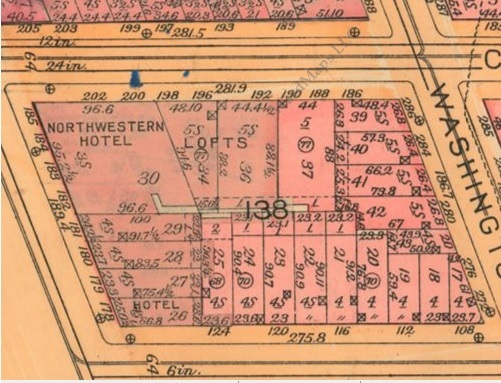

North Western Hotel

185 West Street, corner with Chambers Street (built 1886-1887, demolished 1960s)

The Northwestern Hotel, also written as the North Western Hotel, was located at the corner of West Street and Chambers Street, as part of the larger Washington Street Market area. It was built in 1886-1887 as three new three-story brick structures to be used for stores and a hotel.

“Sign from the Northwestern Hotel” early-mid 20th century. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo and Joseph Mitchell, 1979.054

Its structure was typical of 19th-century waterfront hotels that served a clientele of seamen, migrant workers, merchants, as well as sheltering in-house staff of laundry and kitchen workers—similarly to the Seaport Museum’s remains of Rogers’ Hotel and Dining Saloon at 4 Fulton Street, inside Schermerhorn Row. By 1949 the space was being occupied in the following manner: the cellar with a boiler room; the first story with a restaurant and store; the second story with 23 hotel rooms, a kitchen room, heater, and storage room; and the third story with 33 hotel rooms.[4] “Washington Street Urban Renewal Project Site, 5C. Archaeological Historical Sensitivity Analysis” prepared by William I. Roberts IV, for Public Development Corp., March 1986, pp.25-26.

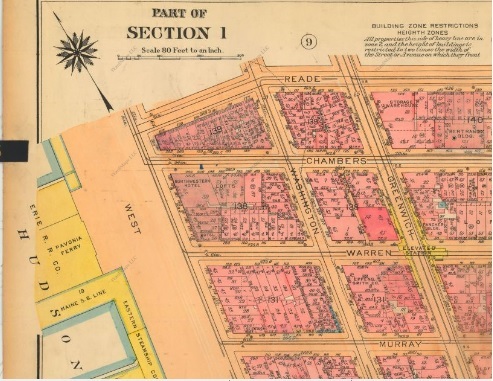

Details of G.W. Bromley & Co., publisher. “Atlas: Manhattan, New York” 1922 Vol. 1, Plate 005.

New York’s taverns and hotels—commercial enterprises offering temporary lodging with meals, drink, and other services—date back to the New Amsterdam era. The first tavern known was operating by 1642 at what is now the intersection of Whitehall and Stone Streets, providing mostly drinking and dining rooms, beside occasional temporary overnight accommodation. Taverns proliferated in the Dutch and English eras, often also being a site for transaction and public business; however, the first “real” hotel was the City Hotel, built in 1794-1795, as a four-story building from Cedar to Thames Streets on Broadway concentrating its business more on lodging of strangers instead of socialization.

Hotels grew as New York City’s port economy accelerated in the early-mid 19th century, from the advent of steam ferries and excursion boats, to a growing number of visiting merchants, seamen, migrant workers, immigrants, tourists and other travelers. In 1837, 60 hotels were counted in the city, but approximately 50 years later, in 1872, 600 to 700 hotels were registered to help accommodate what one observer estimated to be “the largest floating population in America.”[5] “History of New York City’s Hotels” by Steven Jaffe, December 1994.”

The Northwestern Hotel fascinated Mitchell so much that he was able to retrieve a Guest Book from its last years of operation, ca. 1945-1965. The book, in the collection of the Joseph Mitchell papers at The New York Public Library, includes a daily register of hotel guests listing their names, where the guests were from, and their room numbers.

Edgar H. Laing Stores

Corner of Murray and Washington Streets (built 1849, demolished 1971)

This fragment once graced the façade of the Edgar H. Laing Stores, a group of stores at the corner of Washington and Murray Streets, in the heart of the Washington Street Market area. The stores were built by James Bogardus (1800-1874), a pioneer in the design and construction of cast-iron buildings. wooden spans and brick walls, and assembled the four-story structure in only two months, an astonishing feat for the day.

“Spandrel fragment from the Laing Stores” ca. 1849. Gift of Wayne Burkey, 1984.034

Prized for its quick construction time, strength, and fire-retardant nature, his innovation of cast-iron architecture became a foundational step towards the creation of the modern skyscraper.

This particular fragment was not salvaged by Mr. Mitchell, but his papers are full of reports, clippings, and handwritten notes of the dramatic story of the building demolition and loss.

After the demolition of the Washington Street Market, the building stood there a few years more, until 1971, mostly thanks to its designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. In early 1970s it became critical to demolish it to continue the urban renewal project, but to do so it was deemed necessary to document and preserve the façade. The store’s components were then carefully saved, numbered, and stored on a nearby vacant lot so that the structure could be reassembled on the campus of the new Manhattan Community College.

“Edgar Laing Stores, Washington and Murray Streets, New York County, New York.” Historic American Buildings Survey. Image courtesy Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.

A few years later, in 1974, however, three men were discovered loading cast-iron panels from the Laing Stores onto a truck in a storage lot at Washington and Chambers Streets. Though 22 broken sections were later recovered in a Bronx junkyard, city officials discovered that almost two-thirds of the façade had already been sold for scrap, at $90 a truckload. The theft became public when Mrs. Beverly Moss Spatt, chairman of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, dashed into the press room at City Hall shouting “Someone stole one of my buildings!” Over a three week period, someone stole more than half of the entire façade, never to be found.[6] “4‐Ton Cast‐Iron Landmark Facade Panels Stolen Here” New York Times, June 26, 1974.

The remaining panels were immediately placed under lock and key, and a hybrid Laing building, combining original and recast components, was planned to be erected in the new South Street Seaport Historic District, but, incredibly, all the remaining pieces were stolen again in 1977.

Left: New Bogardus Building being constructed, 1983. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Right: New Bogardus Building, 2021. South Street Seaport Museum.

A modern structure inspired by the Laing Stores, was then created in 1983, at Front and A modern structure inspired by the Laing Stores was then created in 1983, at Front and Fulton Streets in the South Street Seaport Historic District, although it contains no elements of the original building. The so-called New Bogardus Building, was designed by the architectural firm of Beyer Blinder Belle as a homage to James Bogardus, and as of today it remains intact.

Did you know? James Bogardus’ wife, Margaret Maclay Bogardus (1804-1878), had a successful career as an artist. Her career began in England in the 1830s, and blossomed upon her return to America a few years later. Two of her portrait miniatures—depicting Mr. Boardman and Paul Joseph Revere—are in The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection!

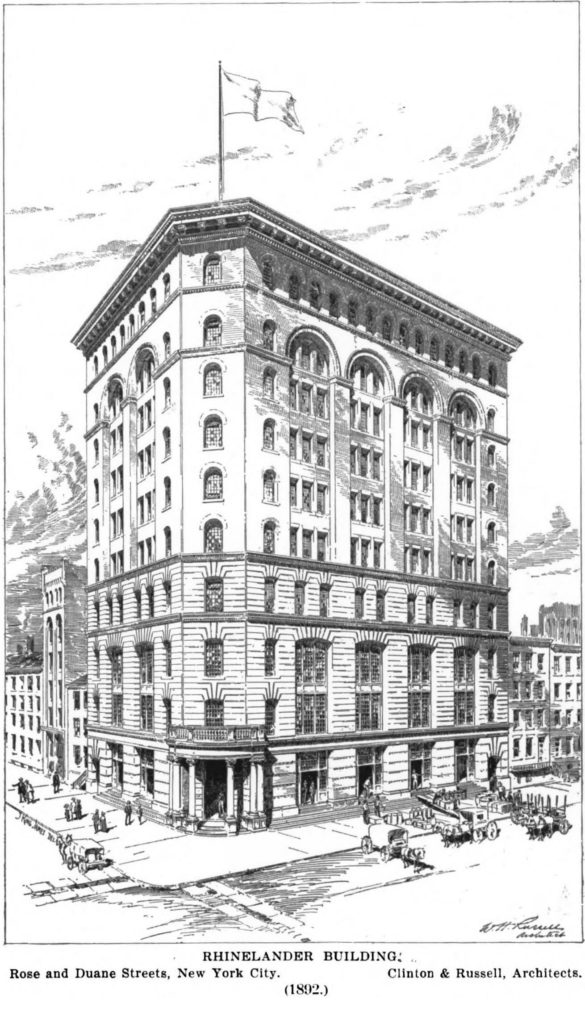

Rhinelander Building

10 Duane Street (built 1893, demolished 1968)

Excerpt from notation for Sunday, October 20, 1968

“Went to the Rhinelander Building, dislodged three sections of lotus (or maybe it is talon) molding and took three of them home (instead of carved brownstone, this molding as well as the egg-and-dart molding maybe be terra cotta.)”[7]Joseph Mitchell papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Box 57, Folder 57.11.

“Ornament from the Rhinelander Building” ca. 1893. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo and Joseph Mitchell, 1979.340.0010 and .0014

These pieces are part of a larger collection of objects of exterior building ornamental components from the Rhinelander Building at Rose and Duane Streets. This building was on the site of the famous Rhinelander Sugar House, built in 1763 and demolished in 1892. The 1763 Rhinelander Sugar House was infamous for being used as a prison by the occupying British forces during the Revolutionary War.

Somewhat amazingly, while nearly all the Colonial architecture of Lower Manhattan was either burned (the Great Fire of 1845 destroyed 345 buildings downtown) or razed, the utilitarian Sugar House survived. By the end of the Civil War the venerable building had not served its original purpose of storing sugar for years. Still in the possession of the Rhinelander family in 1872, it was used as a paper store by James T. Derrickson.

In 1892 the Rhinelander family decided to demolish it in order to erect a modern office building on the site. The second Rhinelander Building was six stories tall, and housed printing trades during the 20th century until its demolition in 1968.

Among the many clippings saved in the Mitchell papers there are Xerox copies of letters petitioning the saving of the building, copies of the Landmark Preservation Commission’s Washington Street Urban Renewal Area report from December 1967, as well as a New York Times clipping dated Monday May 6, 1968, that highlights the fact that “A small, barred window from the sugar house used as a British prison during the Revolutionary War will be spared during the demolition for the new Brooklyn Bridge ramp system.”[8] “City Demolition Workers To Spare Historic Window” New York Times, May 6, 1968. This special window apparently was kept from the destruction of the first Rhinelander Building and incorporated into the newer 1893 building.

When that building bit the dust in 1968 to make room for a new Brooklyn Bridge approach, the window was once again saved and turned into a grim monument. Today, you can see a window from the Rhinelander Sugar House prison at the eastern end of Duane Street behind One Police Plaza.

Excerpt from “A History of Real Estate Building and Architecture in New York City During the Last Quarter of a Century” 1898, p. 609. Courtesy Google Books.

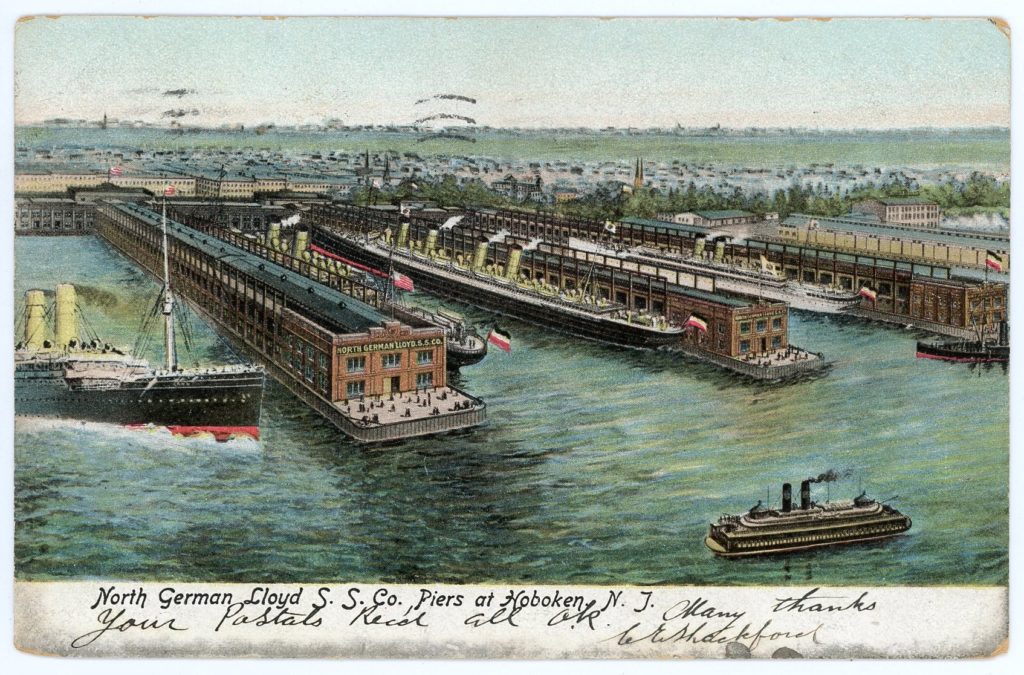

Hoboken Ferry Terminal

Hoboken Waterfront (built ca. 1902, demolished ca. 1960s-1970s)

Excerpt from notation for Friday, October 16, 1970

“[…] went to the Hoboken Ferry, brought section of the iron railing from the balcony fence downstairs, and stood it up just inside the front door, got taxicab, cabdriver helped me put the railing in the back.” [9]Joseph Mitchell papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Box 72, Folder 72.3.

“Hoboken Ferry Terminal’s decorative spikes and balcony scrolled decorations” ca. 1905. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo and Joseph Mitchell, 1979.339.0015 and .0016

Between October and December 1970 Joseph Mitchell did various expeditions to salvage small pieces from the Hoboken Ferry Terminal, which at the time was in heavy disrepair due to the fact that most waterfront cargo, industry, and transportation migrated away from Hoboken in the 1960s.

At the end of World War I, the federal government retained ownership of much of Hoboken’s piers. The great passenger steamship era of Hoboken was effectively over; however, during World War II, Hoboken’s waterfront once again buzzed with activity. Thousands of ships were outfitted, repaired and rebuilt for war-related purposes at the Bethlehem Steel and Todd Shipyards in Hoboken, including the renowned ocean liners RMS Queen Mary and RMS Queen Elizabeth.

In 1963, the Holland America Line, one of the remaining major passenger lines utilizing the Hoboken waterfront, moved across the Hudson. In 1967, the remaining ferry boat services between Manhattan and Hoboken were discontinued, and both the historic Todd Shipyard and the American Export Lines transferred their business and cargo activities to Brooklyn.

After World War II, freighters and liners continued to use Hoboken docks with declining frequency. In 1952, the U.S. Maritime Administration signed a 50-year, three-party lease with the City of Hoboken and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to operate the former steamship complex as a cargo terminal. A major reconstruction project of three Hoboken piers and adjacent upland area was undertaken by the Port Authority. A feasibility study at the request of, and in close cooperation with, the City of Hoboken also started to work out a mixed-use waterfront redevelopment project, leading to today’s Hoboken Waterfront Park—one of the top 10 urban parks in the nation.

This new ferry complex, made of a masonry bulkhead house, three steel and concrete pier sheds, and a sea wall, was built on the same site with careful consideration to fireproofing the construction. Each of the buildings was two stories high, so when ships arrived cabin passengers would disembark through the second level while their baggage, and the steerage passengers, would disembark through the first level. Additionally, people who came to welcome friends and family or to see them off on a North German Lloyd steamship could safely watch the ships come and go from the top of the bulkhead house to avoid crowding and chaos on the piers.

“North German Lloyd S.S. Co. Piers at Hoboken, NJ” September 27, 1906 (postmark date). Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0295

The Scope of Historic Preservation

The scope of historic preservation in the United States has expanded significantly beyond its original goals of saving the homes of prominent Americans. Historic preservation received a great deal of its current force from the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which codified the government’s commitment to protecting the nation’s historic resources. The act gave structure and direction to the modern version of a discipline that traces its American roots to Ann Pamela Cunningham’s crusade in the 1850s to save Mount Vernon by establishing a number of new regulations and agencies, which increased the need for qualified professionals to develop, implement, and enforce the new laws.

Today, most preservation professionals work within a framework of regulations intended to protect the historical integrity of the structures, districts, and landscapes that help to define our cultural identity, balancing their background in historical research with an ability to work with, or within, a government bureaucracy—negotiating and compromising with a range of individuals and institutions. This system is clearly different from the 1960s, when an individual could have stopped by a site being redeveloped or abandoned to pick up a few architectural elements for personal research, as Joseph Mitchell did.

Today, museums like ours tend to not collect archaeological artifacts or architectural elements donated by passionate individuals like Mitchell, but accept donations from preservationists and archaeologists working in architectural firms, city planning offices, economic development agencies, historic parks, and construction companies.

After spending some time with the Joseph Mitchell papers, (and the gracious archivists at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library) I have a renewed interest in and respect for the work of historic preservationists of the past, and the fact that we continue to build upon their work, closing information gaps and documenting their work.

Every preservationist and cultural heritage professional appreciates the built environment. We are committed to saving these valuable resources for future generations, and we are grateful to our predecessors for salvaging what would have been lost.

Additional Readings and Resources

“Giving Preservation a History: Histories of Historic Preservation in the United States” by L. Feireiss and R. Klanten; published by Routledge, December 5, 2003.

“Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America” by William J. Murtagh; published by Wiley, September 5, 2005.

“Historical Profile of Hoboken Piers” produced by The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, January, 1984. Hoboken Buildings & Real Estate Collection, Gift of Bob Maier. Hoboken Historical Society 2005.079.0023.

“History, the Past, and Public Culture: Results from a National Survey” by The American Historical Association (AHA).

References