An intern’s analysis of the collection research process

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Clara Reigosa Lombao, Collection Management Intern

June 26, 2022

My favorite thing about museums is that they are the intermediary between objects, history, and people. During my recent internship, I learned how to research, preserve, and document an art collection. I got a real sense of how a collections management department functions, and I developed skills as a future museum professional.

One of the first objects I was tasked to study was a Royal Doulton fruit plate from the Inman Line Steamship Company. I was excited to research this piece for two reasons.

First, and most importantly, the department was interested in having more information about this object.

Secondly, and on a personal note, this plate reminded me of the ceramic industry of Sargadelos, in the northwest part of Spain, close to where I am from. In the past I read a lot about these ceramics, and I knew that plates and tableware are a significant source of information about history, heritage, and personal lives. As you read this article, I hope you’ll agree.

Further, the intention of this blog post is not only to tell the history of this museum piece, but also to share how the Collections Department works while researching artifacts.

The Starting Point

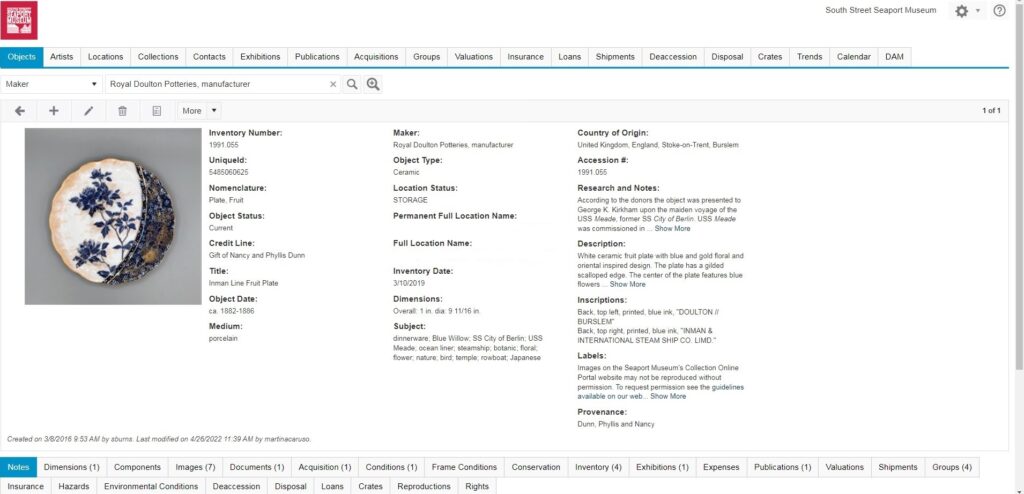

The first step is to review the Museum’s information on the object. To that aim, I checked the collections management database where there are records for each and all objects accessioned in the collection.

Before this online implementation, the “database” was made up of filing cabinets full of folders, one for each object, containing all the relevant documents. Museums still keep these hard-copy archives as reference because the digitization of all these papers take time as well as to preserve a backup for the digital records. Today, online databases are now a more efficient way to handle collection information, on-site and remotely.

The interface you see above belongs to the Museum side of the database, with information that the Seaport Museum’s collections staff members monitor, update, and review. However, there is also a public version, the Collections Online Portal, where online visitors can explore the museum collection and look at some details of the museum pieces. Here you can see the Inman Line plate’s entry.

Getting back to the research, the database gave me the basic information to start my project. So far, I knew that this plate was given to a man called George K. Kirkham while he was on the maiden voyage of a ship called USS Meade in 1898, previously known as SS City of Berlin. The man who received the plate was the father or the son of H.P Kirkham, who presumably owned a shipyard in Brooklyn.

The plate had two stamps which showed it was related to a British pottery brand (Royal Doulton) and a steamship company (Inman & International Steamship Co.). Finally, the object was donated to the Seaport Museum by two people, Nancy and Phylis Dunn, who were great-great-granddaughters of George Karkeek Kirkham (1815-1868).

All this first information helped me organize my research and think about how I could start working on this object. I felt that the best option would be to divide the investigation into the three topics that stood out from the database information: the ship, the Kirkham family, and the plate. These three stories will allow me to understand the plate’s history and how it ended up in the collection but, most importantly, why it is essential to keep and preserve it in a museum like ours.

The ship: SS City of Berlin and USS Meade

The ship’s history is relevant in this research because we know the plate was given to Mr. Kirkham while onboard. So, I needed to understand the relationship between the vessel and this tableware piece. All the information I had was that the ship was called USS Meade, and previously SS City of Berlin. The prefix USS means “United States Ship ”, and serves to identify a commissioned ship of the US Navy. On the other hand, SS prefix means “screw-steamer” or “steamship,” and it was used to refer to the ship’s propulsion or purpose. So the first question was, when, why, and how did this ship change its name? And how does this affect the plate’s history?

SS City of Berlin

It is pretty easy to find information about the ship by searching online as there are several websites where you can discover its history. However, it is essential to check the websites’ credibility and look up different sources to see if they share the same data.

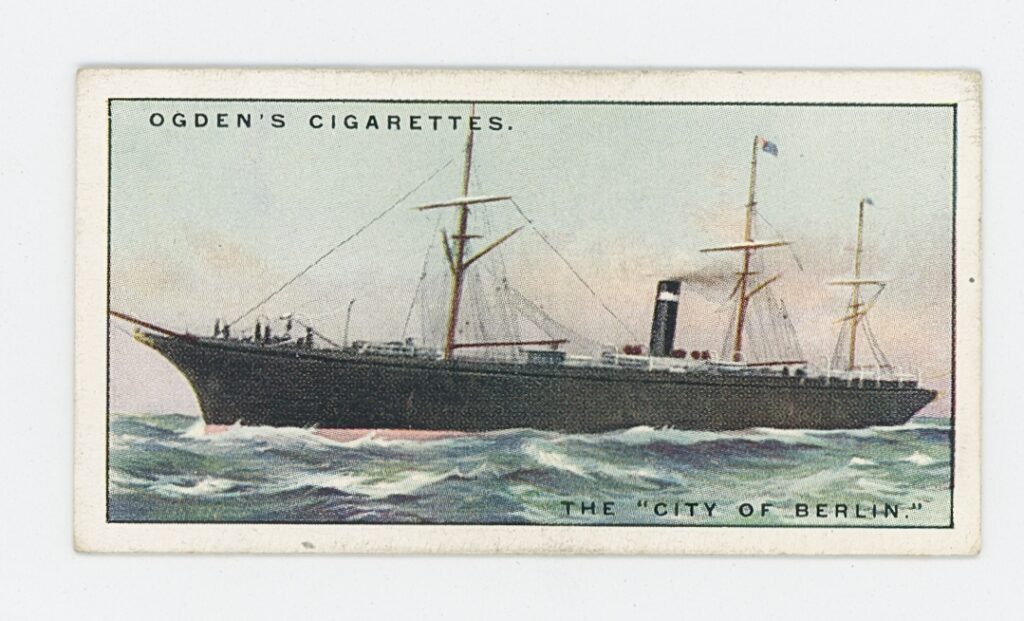

City of Berlin was launched in October 1874 and made her maiden voyage for the Inman Line, from Liverpool to New York, on April 29, 1875. The Inman Line company was formed in 1850, and in 1886 International Navigation Co. purchased their assets, operating under “Inman & International SS Co.” In 1892, the U.S. Mail contract was awarded to Inman & International, and some of its ships started to operate under a U.S. flag and others under a newly created British corporation[1] “Inman Line/Liverpool and Philadelphia Steamship Company/Liverpool, New York and Philadelphia Steamship Company”, The Ship List.. All of them were called International Navigation Co. At this moment, the City of Berlin was renamed Berlin. Berlin served on America’s Southampton-New York service from March 1893 to August 1895. She was then placed on Red Star’s Antwerp-New York service and stayed on that route until the spring of 1988 when she returned to Southampton for two roundtrips to New York.

Ogden’s Branch of the Imperial Tobacco Co., publisher. “City of Berlin Cigarette Card” 1929. Der Scutt Ocean Liner Collection 2001.030.0121

The New York Times published two articles, in 1875 and 1877, describing the City of Berlin. This information is interesting because it explains the main features and helps us understand how the plate was used by the ship’s passengers. Therefore, the information related to the First Class accommodations is especially relevant, although the articles did not mention anything specifically related to the ship’s dinner services[2] “The City of Berlin”, published by The New York Times on April 6, 1875 and “Sketch of the City of Berlin”, published by The New York Times on December 7, 1877..

USS Meade

In 1898 Berlin became the U.S. troop transport ship Meade and was used to transport troops to the Philippines during the Spanish-American war (April-August, 1898). As I said before, beyond the information available on websites, it is interesting to compare and contrast similar information from different sources. It is always good to find a primary source that documents what is said on a web-based source. On July 9, 1898, the New York Times announced a rumor about the sale of SS Berlin to the U.S. Government[3] “Government buys City of Berlin”, published by The New York Times on 9 July, 1898..

I was lucky to find a government report from January 21, 1922, which described troop transport services during the war. In this document, there is a list of the army transports owned by the United States and their basic information. The Government purchased Meade from International Navigation & Co. on July 18, 1898 for $400,000[4] “Government Transports and the Transports Service”, 57th Congress, 1st Session, Senate, Document No. 369..

There is also information about Meade‘s trips during the Spanish Civil War. Nevertheless, one of the most interesting things mentioned is the amount paid for repairs to army transports. In the case of the Meade, there is a list of several companies that worked on it in San Francisco, Manila, Honolulu, and New York. In the latter, one of the companies is “H.P Kirkham & Son”, which received $3,898.00. This is the first time I found a name related to the man who received the plate, following the museum’s records. So it was time to take a look at this family name.

The Kirkham family

At this moment, I had two names that I needed to relate, George K. Kirkham and the company H.P. Kirkham & Son. Although I assumed this company worked in ship repairs, I wanted to have as much information as I could about it. I found a commission report created to investigate the war department during the Spanish-American War. It gave me some valuable information about the company and the war itself[5] “Commission appointed by the president to investigate the conduct of the war department in the war with Spain”, 56th. Congress, 1st Session, Senate, Document No. 221..

What can be deduced from this report is that there was an investigation because there were several problems during the War. There are several interviews with people connected to this event, from physicians to shipwrights, to analyze what they did wrong during several battles. One of the interviewees is Henry P. Kirkham on November 25, 1898. Here, he confirms that he lives in New York and his business is shipwright. Moreover, he explains that his duty was “the fitting of the transports”, “my orders were to go onboard and make all the repairs and work out of the number of troops a ship could carry, according to the spaces, etc.”. The rest of the questions are connected to his work transforming the ship into a navy vessel and what they could have improved regarding his work. This document, along with the report mentioned above, proves that H.P. Kirkham was one of the companies in charge of the transformation from SS Berlin to USS Meade.

Now, I need to know who George K. Kirkham was and how he was related to Henry P. Kirkham. There were a couple of notes in the object entry regarding these men. First, the donors, Nancy and Phyllis Dunn, were the great-great-granddaughters of George Karkeek Kirkham (1815-1868). But it also mentions that George K. was the name of H.P.’s father (and the name of the son of H.P.). Trying to know more about this family, I found a New York Produce Exchange report between 1899 and 1890. Here, it appears the name of George K. Kirkham and Henry K. Kirkham, whose business was repairing ships with offices in D 9-10 Produce Exchange[6] “Report of the New York Produce Exchange from July 1, 1899 to July 1, 1900”.

Therefore, regarding the dates I managed, there was only one possibility. George Karkeek Kirkham (1815-1868) was the great-great-grandfather of Philis and Nancy Dunn. He was the father of Henry K. Kirkham and the grandfather of George K. Kirkham, who received the plate during the maiden voyage of the USS Meade. How and why was this plate given to him?

The Inman Line Fruit Plate

Once I placed our protagonists, the plate, and the man who received it in a specific place (USS Meade) and at a particular time (between July and November of 1898), I needed to know more about the object itself. Why was this plate there? If I wanted to have all the information about this piece of tableware, the first thing I had to do was turn the plate upside down and check the reverse. To do that, I needed to see the plate in person, which meant a visit to the Museum’s collection storage.

Now, normally, interns would have had more access to collections storage than I did during my internship, but I was working partly remote that season as there were still some restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The South Street Seaport Museum collection storage is similar to other museums. Depending on the type of museum, there will be more shelves, drawers or racks. In this case, the museum’s wide variety of collection mediums needs all of these different storage types. The Collections Department keeps the Inman Line fruit plate with other ceramic objects in shelving units, with each piece placed on a layer of foam. I needed to take it out of the shelf and touch it with my hands in protective gloves to check the object’s reverse, without leaving fingerprints and stains. Once I had all set, It was the moment of studying and enjoying.

In the reverse, I saw 6 different marks:

- one number (black): 41.55 (South Street Seaport Museum Inventory Number)

- one number (blue): A3606

- one Royal Doulton seal (blue)

- one Royal Doulton seal (white)

- one Inman & International seal (blue)

- one abstract mark (blue)

The three seals led me to the manufacturer, Royal Doulton, and the ocean liner, Inman Line. Studying these three seals in depth gave me much more information.

Royal Doulton

Royal Doulton is a ceramic manufacturer founded in 1815 by John Doulton. In the beginning, it operated in Vauxhall, London. Then it moved to Lambeth, where it employed over 200 artists and designers from the art school. In 1882, it opened a factory in Burslem. In 1901, it received a royal warrant and permission to use “Royal” in its name. Nowadays, it produces not only ceramic but home accessories of all types.

Royal Doulton marks

There are two different Royal Doulton marks in the reverse. One of them is printed in blue color, and the other one is imprinted into the ceramic surface. The middle part of both of them is the same, a crest with the name “Doulton Burslem” and the logo of the company, two capital “D” interlocking. However, the blue one has a coronet over it while the other has a “3” over the top and two “8”s under it. All of these differences gave me relevant information about times and dates that I will comment on below. But before that, it is also essential to take a look at the other blue marks around, the number “A3606 ” and an abstract blue symbol on the top right.

Firstly, the brand used the name “Doulton Burslem” between 1882 and 2004, a long period that I needed to narrow down. The impressed mark is probably the first one, since it had to be done during the plate’s manufacturing, and also because its form is known to have been used between 1882 and 1902. The blue seal also with the coronet can also be dated between 1886 and 1902[7] “Doulton marks”, Antique Marks.. The blue number, which begins with an “A” is another mark from the manufacturer. This number identifies the series, and it gives information about the type of ceramic and dates of production. In this case, the “A3606” means this is fine earthenware done between 1882 and 1898[8] “How to find the age of your Royal Doulton”, Antique HQ.. The abstract mark on the top right part of the plate could identify an artist, but I could not match this symbol with any artists available on a Royal Doulton’s artists’ list.

The Inman Line seal gave me information about dates since the company changed the name several times. In this case, “Inman & International Steam Ship Co.” was the name the company acquired after 1886 when International Navigation and Co purchased it. Therefore, this plate was produced between 1882 and 1902 since the Royal Doulton logo changed after that. Following the ship’s company name, the logo had to be stamped between 1886 and 1892.

Moreover, this stamp confirms that the Inman Line used the plate, probably as tableware for the upper classes in its ocean liners. However, I could not find any information about this use beyond that it was common to produce specific tableware for these ships. The Collection Online Portal has “Ceramic Highlights” where you can search several examples of ocean liner’s dinner services. However, there was only one other example of Royal Doulton pottery that I could compare to my plate in the Museum’s storage.

Royal Doulton, manufacturer, Furness Bermuda Line Creamer, ca. 1919-1966. Ocean Liner Museum Collection 2003.007.0328

Throughout its history Royal Doulton has produced sets of tableware for hotels or airlines. The company even made special bone china service and crystal glasses for Concorde’s inaugural flight in 1978; the British manufacturer also sent the first bone china to space in 1984 on the space shuttle Discovery[9] Doulton, Michael and Lee, Vinny. Discovering Royal Doulton. Shrewsbury: Swan Hill Press, 199, p. 68, p. 84..

The plate’s design

There is not much information about the plate’s design and uses, beyond the fact that it was used by wealthy passengers of the Inman Line’s routes. I also couldn’t find examples of this exact plate in other museum collections.

However, I found very similar designs in online auction houses. This may be because this plate ended up being memorabilia that passengers kept for themselves, and eventually, it was passed down to relatives.

The plate’s design follows a “Willow Pattern”, an image produced by British engravers in the late eighteenth century and derived from Chinese models. This example is in blue and gold.

In the central part, there is a plant with flowers, and on one of the sides there is also a floral pattern and two small vignettes depicting plants, trees, and some buildings. This plate was almost certainly part of a full dinner service set that included cake and tea plates, cups, saucers and other types of tableware.

Conclusions

Three different stories converge on this Inman Line fruit plate. The plate was produced at the end of the nineteenth century by the British manufacturer Royal Doulton. We cannot know if the design was specifically created for the ocean liner or if it was a previous design that ended up being part of the tableware of the ship company. Whatever the case may be, we suppose that the Inman Line used the plate in one of its routes crossing the Atlantic Ocean to serve food to upper-class passengers.

Additionally, the plate is related to the story of the family of the two donors, Nancy and Phyllis Dunn. They were descendants of George K. Kirkham, the man who received the plate during the maiden voyage of USS Meade in 1898. The ship was transformed from an ocean liner to a navy ship in July 1898, since the United States government needed to convert vessels quickly for army purposes during the Spanish-American War. In the records, I could confirm that Henry P. Kirkham and his son, George K. Kirkham, were working in New York between 1899 and 1890 repairing ships and also that their company (H.P. Kirkham & Son) was in charge of the Meade transformation. Hence, George K. Kirkham was related to the USS Meade as a shipwright.

According to the donors, we know that George K. Kirkham was a shipwright and that plate was presented to him on the maiden voyage of USS Meade. However, we cannot confirm how or in what situation the plate was given to him, but we must assume that the plate had lost its primary use (being part of dinner service for wealthy passengers) at the moment that the U.S. Government purchased the ship for war purposes. It may be that the plate was a gift for George K. Kirkham, as a way of being thankful to him for all the work done in the ship’s refitting. This could also be the reason why he kept the plate in his family as an heirloom object.

Hence, the plate was passed down several generations until Phyllis and Nancy Dunn thought it would be better to preserve it in the South Street Seaport Museum. Thanks to them, and the rest of our museum donors, today we can tell not only the Inman Line plate’s history, but also connect it to the Spanish-American War, the shipyard companies or the pottery manufacturers, and ultimately and most importantly, the history of New York City’s port.

Sources

Baber, Mark. “City of Berlin”, Great Ships. Last access May 5, 2022.

“Our Story”, Royal Doulton. Last access May 5, 2022.

Portanova, Joseph J., PhD, “Porcelain, The Willow Pattern and Chinoiserie”, New York University, 2022.

References

| ↑1 | “Inman Line/Liverpool and Philadelphia Steamship Company/Liverpool, New York and Philadelphia Steamship Company”, The Ship List. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “The City of Berlin”, published by The New York Times on April 6, 1875 and “Sketch of the City of Berlin”, published by The New York Times on December 7, 1877. |

| ↑3 | “Government buys City of Berlin”, published by The New York Times on 9 July, 1898. |

| ↑4 | “Government Transports and the Transports Service”, 57th Congress, 1st Session, Senate, Document No. 369. |

| ↑5 | “Commission appointed by the president to investigate the conduct of the war department in the war with Spain”, 56th. Congress, 1st Session, Senate, Document No. 221. |

| ↑6 | “Report of the New York Produce Exchange from July 1, 1899 to July 1, 1900” |

| ↑7 | “Doulton marks”, Antique Marks. |

| ↑8 | “How to find the age of your Royal Doulton”, Antique HQ. |

| ↑9 | Doulton, Michael and Lee, Vinny. Discovering Royal Doulton. Shrewsbury: Swan Hill Press, 199, p. 68, p. 84. |