Inventorying the Toys and Games from the Museum’s Collections

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Elizabeth (Lizzie) Shack, Collections and Exhibitions Management Intern

June 26, 2025

Throughout my Collections and Exhibitions Management internship, I have been granted the incredible opportunity to hone my collections management skills through a range of projects. This has included assisting with the preparation and installation of the newly-opened milestone exhibition Maritime City, as well as cataloguing the collection of Robert Warner (1956–2023) contemporary works on paper, and even preparing some of the Museum’s Maps and Charts database entries for addition to the Collections Online Portal. For my final project, I was presented with the opportunity to inventory a sampling of the historical toys, games and puzzles in the Museum’s collections. This project has served as an apotheosis of sorts, representing a culmination of the skills I have acquired throughout my time at the Seaport Museum.

If you are anything like me, you may be wondering why a maritime museum has over 1,300 toys and games in its collections. How do they relate to the South Street Seaport Museum? While, yes, many of the toys depict various ships and seafaring activities, others reflect the institution’s mission to preserve and interpret the history of New York City as a world port—a place where goods, labor, and cultures are exchanged through work, commerce, and the interaction of diverse communities.

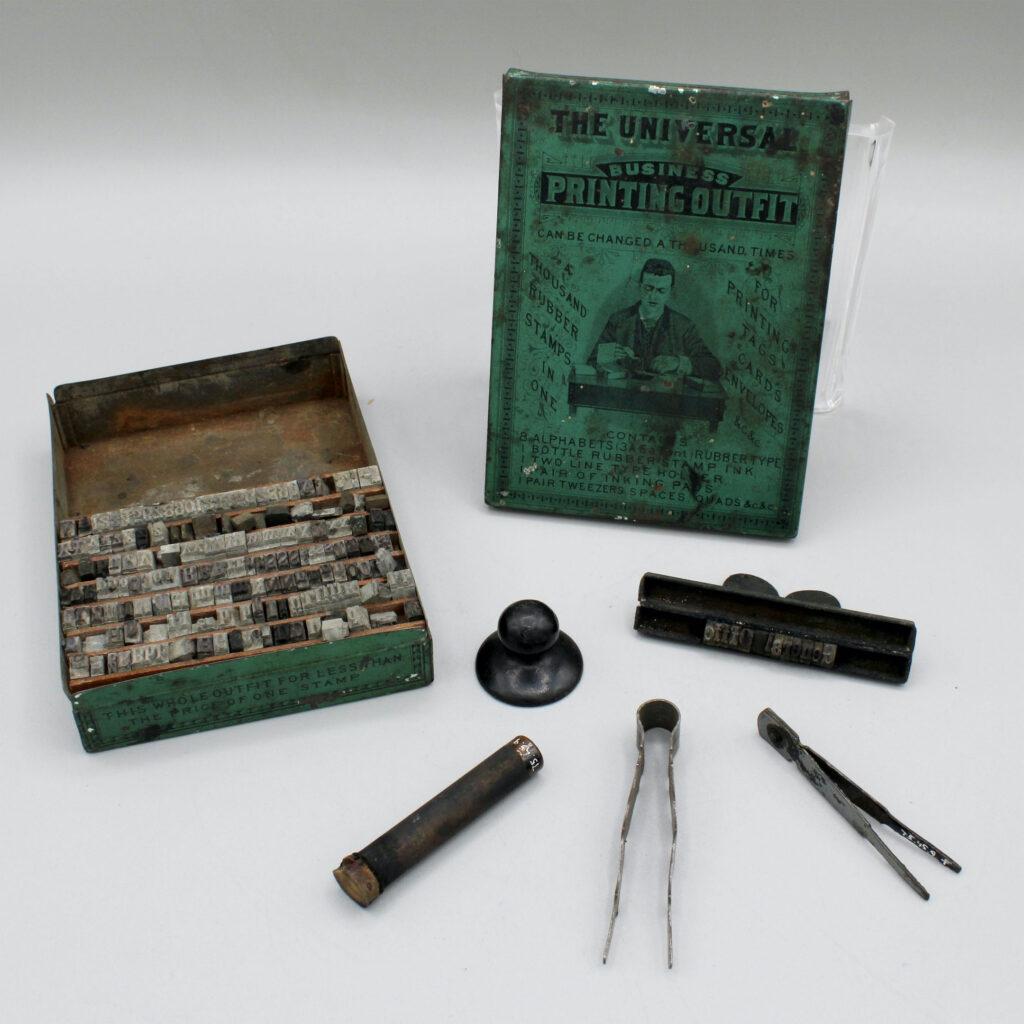

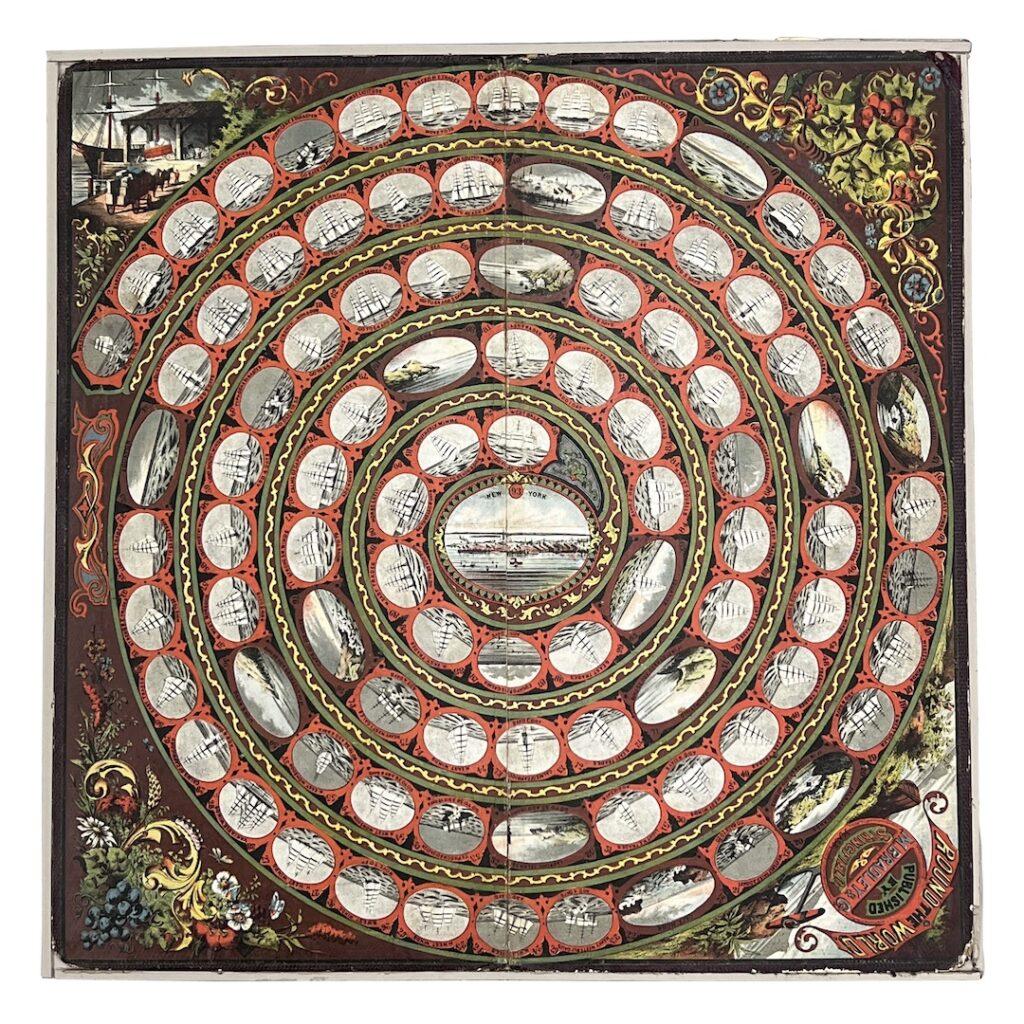

Toys, games, and puzzles offer an interpretive and educational window into the critical role of play in physical, social, and intellectual development, and the ways in which play reflects cultural history. The collection thus holds primarily 19th century toys documenting the leisure pursuits of American families including souvenir sailor dolls, lithograph printing kits, board games and puzzles, cast iron mechanical toys (from fire engines to circus parades!), automata, and of course, ship model kits.

Left: The Universal Printing Outfit, 1879. Gift of Paul Lippman 1975.045.0009.A-.F

Center: Round the World, ca. 1873. Museum Purchase 1990.015

Right: Sun Princess Sailor Doll, ca. 1973. Ocean Liner Museum Collection 2003.007.0135

The Inventory Process

The goal of the Toys and Games inventory project was to review and update the database entries to meet current standards of practice, with the most accurate and up-to-date information available[1]This includes removing unwanted, duplicate, or incorrect data to improve the quality and reliability of the database. This process, also known as data cleaning, involves identifying and correcting … Continue reading. This ultimately allowed us to upload over 70 toys (and more to come!) to the Collections Online Portal to share them with all of you at home. Given that the Seaport Museum’s collections include 28,000 works of art and historical artifacts, along with over 80,000 archival materials, the portal is an incredible product of the current technological age—enabling the Museum to share more of the collections with the public than can ever be displayed physically.

Most of the current toys, games, and puzzles’ records in the Museum’s collections database were outdated, in need of updating to match our current standards and become publicly shareable[2]Instead of relying on paper, most museums use cloud based collections management software, or databases, to keep track of their collections and related information. They can be customized to an … Continue reading. Standardized database entries are part of collections care; they encompass large sums of crucial information—such as creators and manufacturers, dates, donors, and historic research—that can be easily lost if not recorded correctly or in alignment with technological advancements.

The inventory process includes several steps for each object to ensure all pertinent information is accurately documented and easily understood. When cataloguing an object, we record observable information; measure the object for its dimensions, record its condition to maintain a record of any damage or change over time, take photographs of full and detailed views, and describe the object. We also look for indiscernible information; information not found by visual inspection.

Each object has its own story if you know where to look, this can include information such as the object’s date, manufacturer, and other relevant context accessible only through more intense research. Even when the avenues for research have been exhausted, sometimes we are unable to find indiscernible information. Though, it makes it all the more exciting when you can take a deep dive into an object and reunite it with its context.

Keeping Track

Some objects have more needs than others. To keep track of objects, each is given a unique accession number that, in itself, notates important information. The accession number is composed of three main parts: the year the object was acquired, the numerical order in which the object was donated within the year, and the object’s number within the specific donation (e.g. 2001.004.0013)[3]”Museums have tried many numbering systems over the years. The most important thing about a number, whether permanent or temporary, is that it be unique because it is the link between the … Continue reading.

Several of the toys have detachable parts, or components, that must be accounted for to avoid loosing track of their location and potential loss. This is done by adding a letter to the end of the object’s accession number. These numbers are associated physically with the object, and occasionally during my inventory project I found them missing from the actual objects.

The process of marking an object with an accession number consists of writing the accession number directly on the piece, but it is a completely reversible practice. There are several methods of doing so, chosen depending on the object’s material.

For the majority of the toys and games I worked on, I used Paraloid B-72 (or Acryloid B-72), a common material used by museums and collections for marking and labeling objects made of hard materials such as metal and wood.

B-72 is a clear acrylic resin in acetone that serves as a barrier coat, protective layer, and even adhesive for labels. It is used as a base for direct marking on the object’s surface, especially for objects that are less sensitive or where a label is not suitable.

Here’s a breakdown of how it’s used:

1. Barrier Coat: Before marking an object, a thin layer of B-72 is brushed onto a discreet area, often the underside or edge. This provides a surface that is less likely to be damaged by the marking process and can be easily removed if needed.

2. Direct Marking: A special ink pen can be then used to write the identification number on the B-72 coating. A topcoat of B-67, another type of clear resin, is then applied to protect the mark.

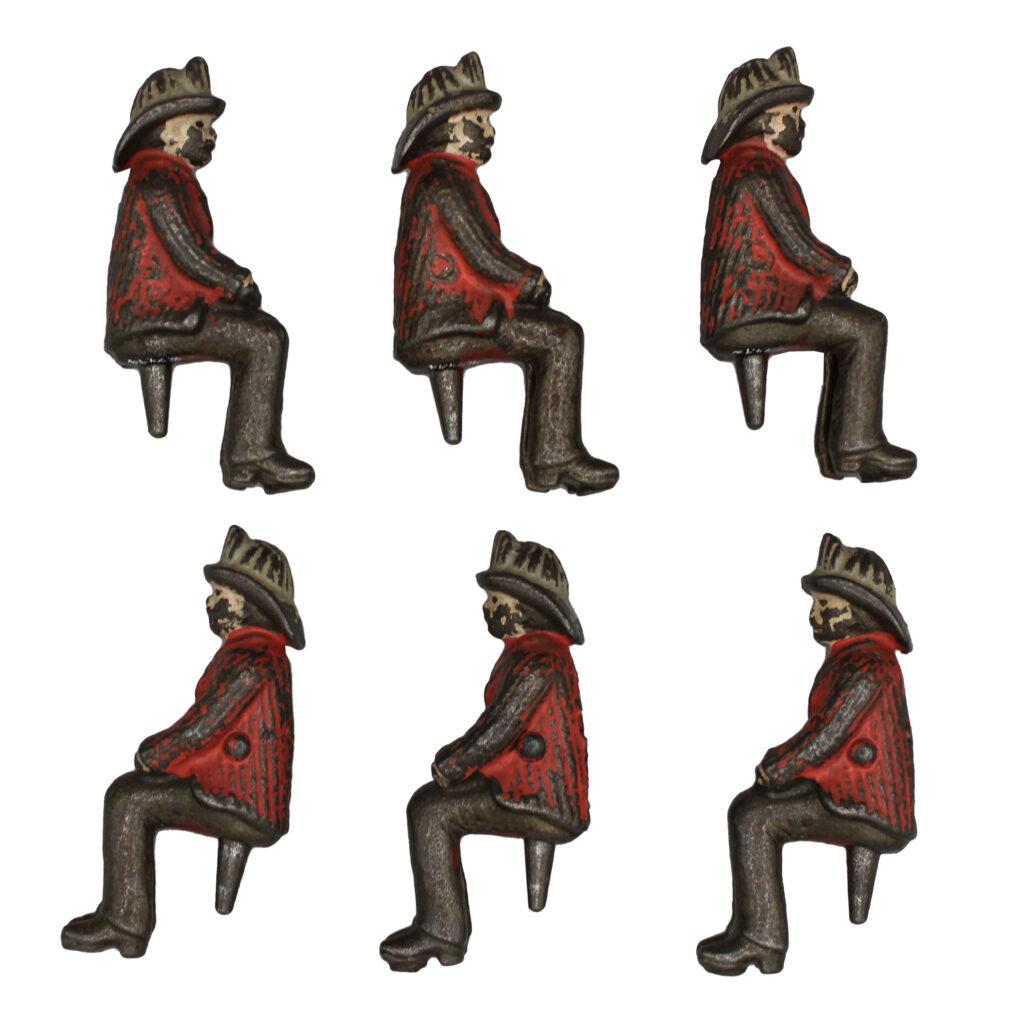

Adding a unique acquisition number and letter to each piece ensures that the components are identifiable if separated from each other. For example, this 1890s cast iron Fire Patrol Wagon is one object, with all of its components together. However, the wagon, horses, driver, and the six figures are detachable. Thus, the wagon became 1991.074.0009.A, the horses became 1991.074.0009.B, the driver figurine became 1991.074.0009.C, and the six firemen became 1991.074.0009.D-.I. Now, say a fireman was misplaced, future collections specialists and cataloguers will be able to figure out where to return it.

Fire Patrol Wagon, ca. 1889-1898. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.074.0009.A-.I

Case Study: Schooner Sultana Model Ship Kit

As a maritime museum, it goes without saying that the collection of toys and games encompasses ship models and modeling kits.

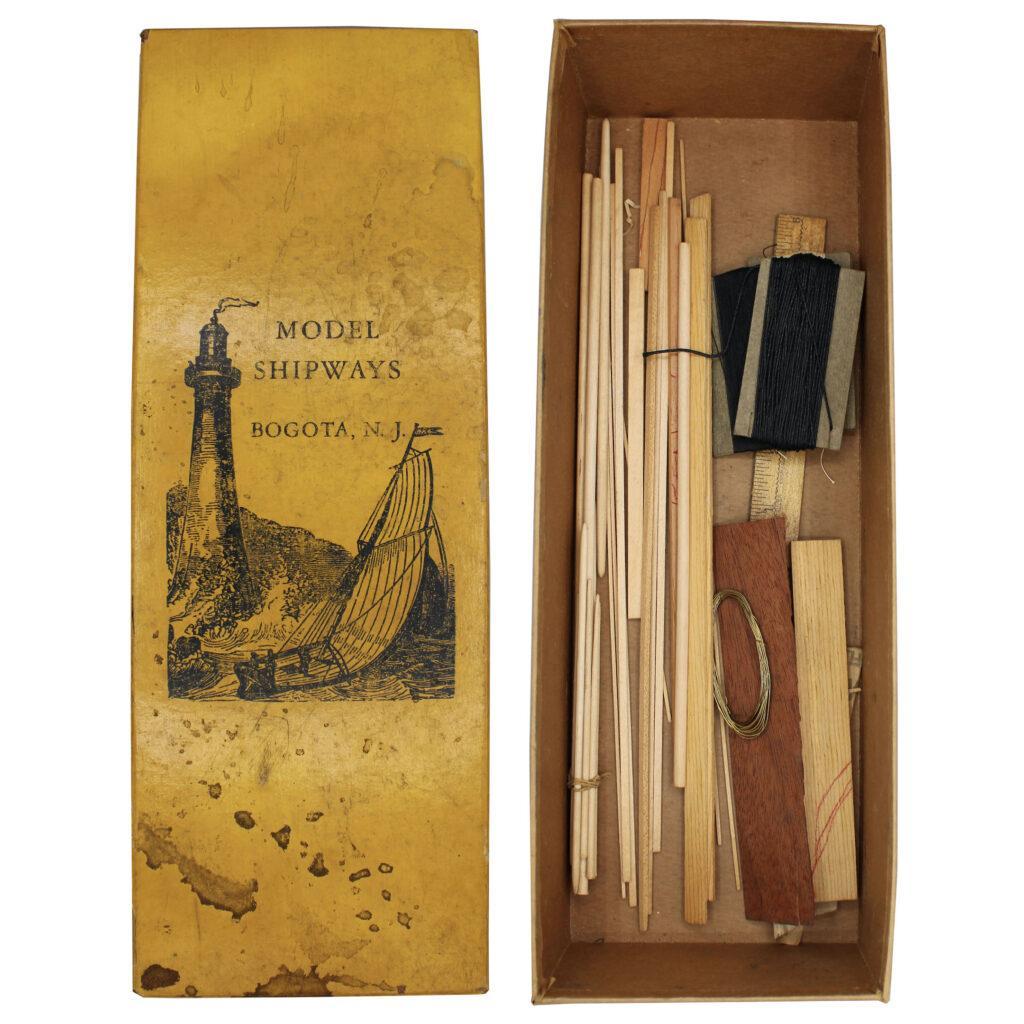

This includes the most intimidating object I encountered during this project, an unbuilt schooner Sultana ship model kit.

When I opened the bright yellow box, I was surprised—yet hesitant—to see that there were seemingly millions of small parts and accessories that had not yet been accounted for, despite the Museum acquiring the object in 1996.

Schooner Sultana Colonel Model Kit, ca. 1964. Gift of Brian Brown 1996.007.0001.A-.T

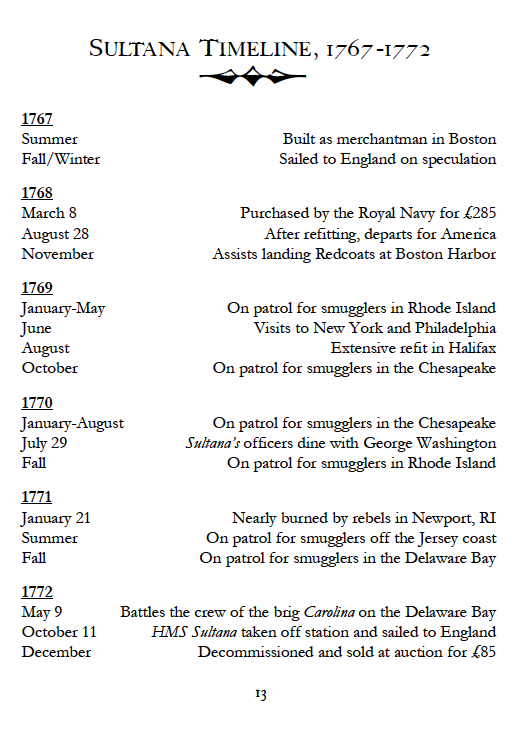

The actual ship Sultana was originally built in 1768 in Boston as a merchant schooner[4]A schooner is a type of sailing vessel, originating in the late 17th century, defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the … Continue reading. It was purchased by the Royal Navy in the same year and played a significant role in the conflict that became the American Revolution, used to search ship’s cargo amidst the implementation of the Townshend Acts[5]“A Guide to the 1768 Reproduction Schooner Sultana,” Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network, Sultana Education Foundation, 2003.. By the end of 1772, after several violent encounters with American colonists, Sultana was decommissioned by the Royal Navy and sold at auction. The rest of her career after decommission is unknown. Today, a replica of Sultana, used for hands-on learning, resides at the Sultana Education Foundation in Chestertown, Maryland. Much like the Museum’s very own schooner Pioneer, Sultana sails actively, providing educational experiences to visitors.

Left: “A Guide to the 1768 Reproduction Schooner Sultana,” pp.13, Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network, Sultana Education Foundation, 2003.

Right: Collections Intern Elizabeth Shack cataloguing Sultana components in storage.

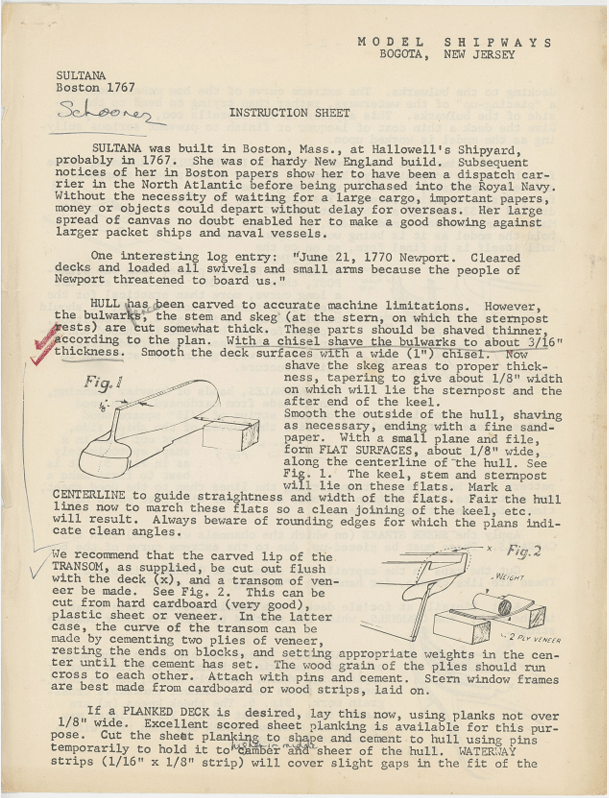

After conducting some online research about the model kit, I noticed that the instructions and plans were missing from the box. I had a hunch that we had to have them somewhere, sending me down a research rabbit hole in our institutional archives. Excitingly, I located the instructions and plans in the model’s accession file, and was able to reunite them[6]Accession files, or records about objects in a collection, “are maintained on an ongoing basis for permanent reference.” The files include “primary sources of information about the object.” … Continue reading. I also discovered that part of the donation was books pertaining to the distributor—Model Shipways from Wayne, New Jersey—including a catalog of models and fittings for sale. This discovery allowed me to not only date the model as ca. 1964, but helped me to identify several of the miniature metal fittings!

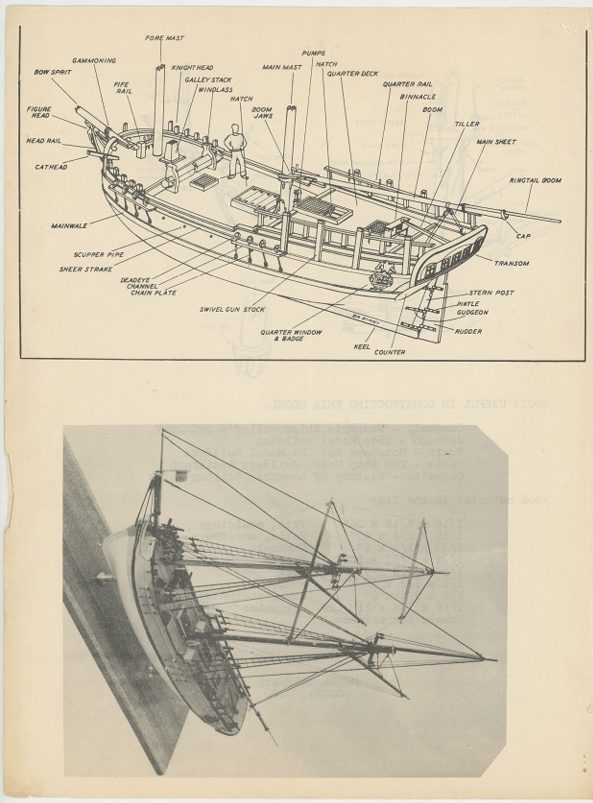

Left: “A Guide to the 1768 Reproduction Schooner Sultana,” p. 13.

Right: Schooner Sultana Colonel Model Kit Ship instructions pp. 1-6

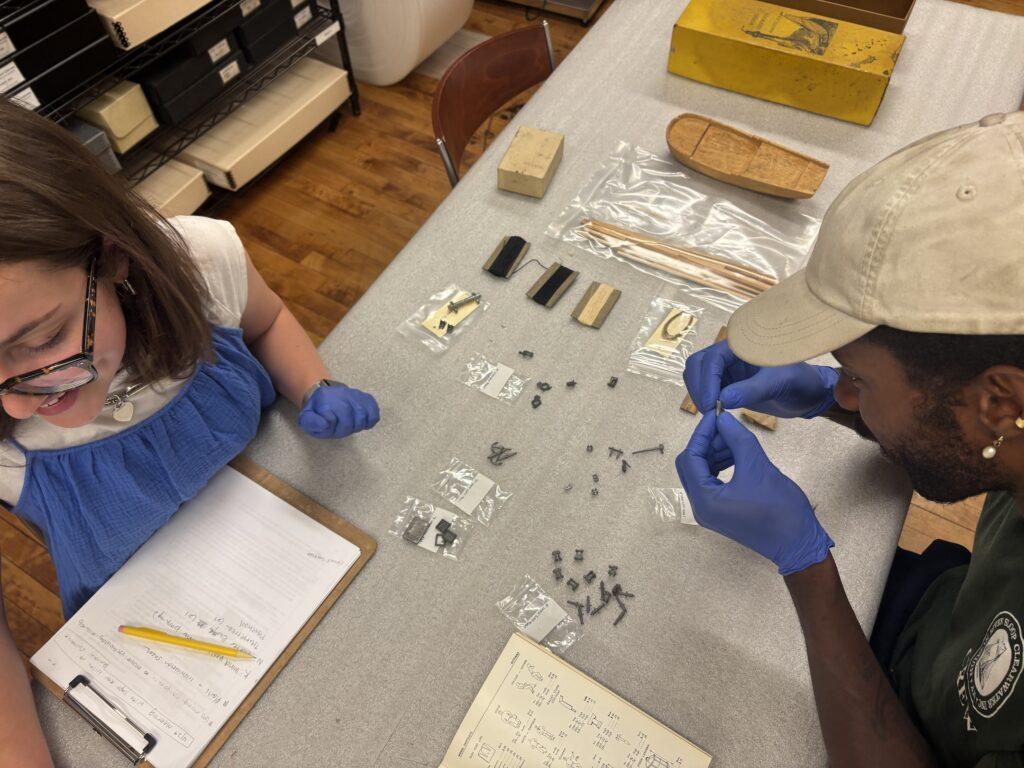

The most difficult part was describing all of the components. While processing the several components and trying to make sense of it all—with my maritime vocabulary still in development—I quickly realized that I needed to call in the help of our incredible waterfront team. Director of Collections and Exhibitions, Martina Caruso, called on the schooner Pioneer’s Captain, Ken Niles, to join us in collections storage (usually reserved for collections staff only) to help me identify the miniature ship fittings. Coincidentally, Captain Niles was the perfect person to call upon, as he previously was the Lead Deckhand on Sultana.

Captain Niles was a tremendous help as he was able to sort through all the small components with expertise, identifying almost all of them with his first-hand experience, and comparing the components to the model’s instructions and plans—something I could have never done without him.

According to Captain Niles, the model appears barely worked on outside of its original state. There is minimal carving of the hull, and no installation work. He also noted that from his experience, many integral components were not included in our kit, including the rudder and masts.

Captain Ken Niles and Collections Intern Elizabeth Shack discussing Sultana components in collections storage.

Schooner Sultana Colonel Model Kit, ca. 1964. Gift of Brian Brown 1996.007.0001.O,M,N

It is such a pleasure to work with staff members from other departments, and see their excitement when working directly with historical objects. Captain Niles lit up when he got his hands on the model, a rare opportunity for non-collections staff. It was also invaluable for me to work with him, as he and his team have such a wealth of maritime knowledge and actual hands-on experience. Without their experience, this object might not have been reunited with its context.

Antique toys, outdated mindset

Disclaimer: the following section contains information and imagery depicting racism and stereotypes.

Not all aspects of this project were fun and games. Some of the imagery associated with several of the toys is quite challenging. Several are blatantly racist.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, toys were one of the routes used to spread stereotypes and false narratives about non-white, non-european culture and heritage. Take this “Kicking Mule” toy (image below on the left) for example, which, according to the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Imagery, portrays:

“[…] a grossly caricatured African American boy riding a mule. When the player pushes a lever, the mule bucks, throwing the rider over its head onto a log on the ground. By involving the player in pretend violence against an African American and implying that such violence is fun, ‘Always Did ‘Spise a Mule’ contributed to a cultural climate in which violence against Blacks was (and still is) acceptable.”[7]“Toys as History: Ethnic Images and Cultural Change – Scholarly Essays – Jim Crow Museum.” by Pamela Nelson. Jim Crow Museum. Accessed April 29, 2025. … Continue reading

Left: Kicking Mule, 1879. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.074.0025

Right: Boy Feeding Fish to Alligator, late 19th century – early 20th century. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.074.0028

Some toys are not as explicitly visually racist, but still carry the connotation.

Without research, I would not have known that the “Boy Feeding Fish to Alligator” toy (above image on the right) refers to the Alligator Bait trope and slur, present in popular culture throughout the 19th and 20th centuries[8]To learn more about the term “Alligator Bait” and its presence in 20th century American media, read the May 2013 “Alligator Bait” blog post from the Jim Crow Museum: … Continue reading. This cast-iron pull toy depicts a boy baiting an alligator with a fish. When the toy is pulled, the alligator’s mouth opens and moves forward while the boy moves back and forth.

When working with antique objects, encountering bigoted imagery and language is nearly unavoidable. Toys like the ones above reflect the racial superiority mindset of the 19th and 20th centuries, reducing people to ethnic and racial caricatures. Often, they “reflected the anxiety White Americans felt as others sought opportunity in the United States.”[9]“What Can a Toy Tell Us About Race?” by Eric Feingold, March 15. 2021. These types of objects reflect the deeply harmful mindset of their time, and continue to represent it. In a museum’s collections, we can focus on education with these objects, simultaneously learning from them without erasing history.

Collections Portal Highlights

Today everyone can enjoy over 70 vintage toys, games, and puzzles on the Museum’s free Collections Online Portal. During the inventory, imaging, and cataloguing project I came across some toys that are more unique than others, and manufacturers with intriguing histories. With that, I will share some of my favorites from the collection!

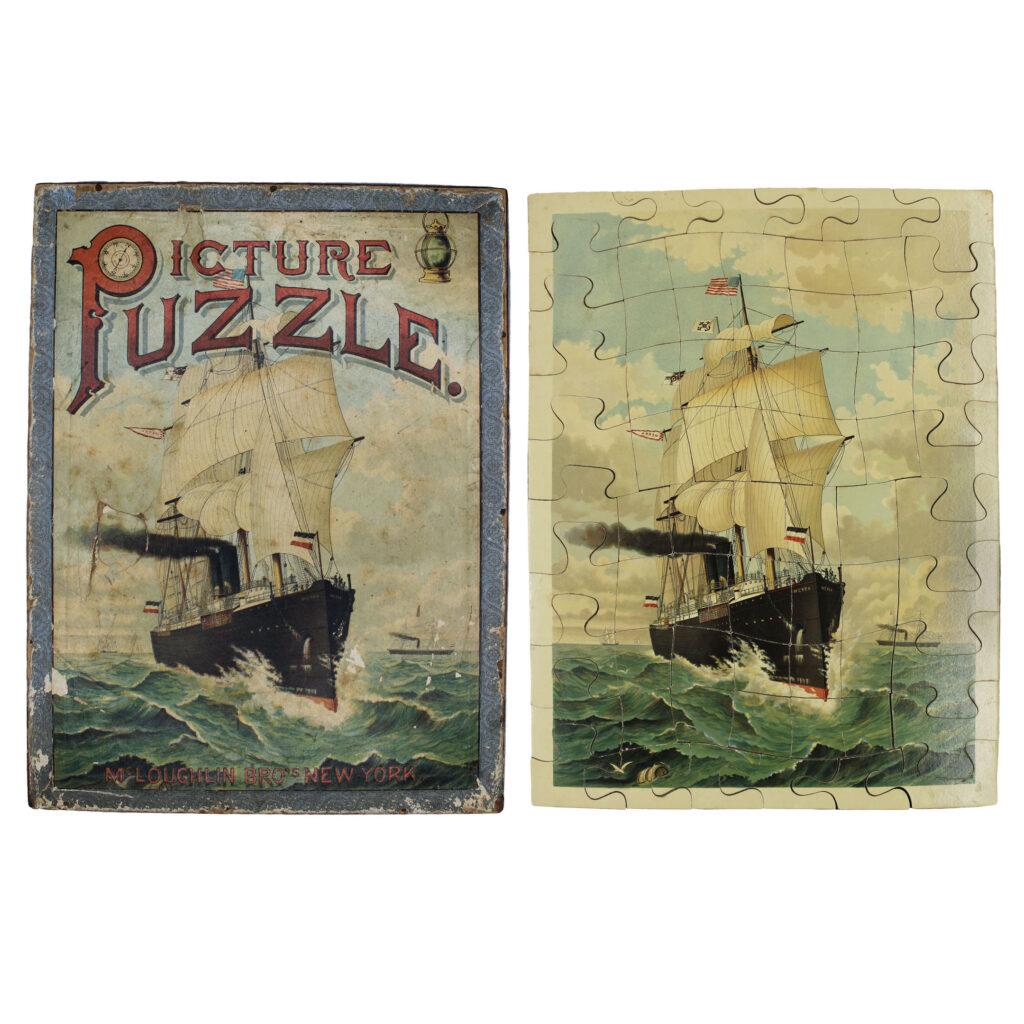

Picture Puzzle

Believe it or not, this 68-piece puzzle is from around 1890! As a puzzle lover myself, I had so much fun putting together all of the pieces and experiencing how puzzles have changed over the last century or so. If you look closely, only the border pieces are truly jigsaw. The middle pieces were more square, which was actually quite difficult to figure out as they don’t fit together perfectly.

This puzzle was manufactured by the McLoughlin Bros., inc., a New York company known for being a pioneer of color printing technologies[10]”Brief History of the McLoughlin Brothers” by Laura Wasowicz. American Antiquarian Society, 2003.. In 1920, it was acquired by Milton Bradley & Co., a company known for games such as Battleship and Connect Four. In 1984, the company was purchased by the famous Hasbro Games, which currently makes games like Monopoly, Trouble, and Jenga.

Picture Puzzle, ca. 1890. Museum Purchase 1994.032.0003.A-.PPP

Bucking Broncho

Cowboy on Horse, Bucking Broncho, ca. 1911. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.074.0032

This toy, dated ca. 1911, is a prime example of a tin mechanical toy. It depicts a cowboy riding a horse on a green platform. When the key is wound, the horse bucks and the cowboy moves forward on his hands.

This toy is quite amusing when you dig into the context. Although the toy represents the American Wild West, its manufacturer, the Lehmann Company, was a German toy company! According to a current Lehmann toy website, the idea was based on Buffalo Bill and the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show.

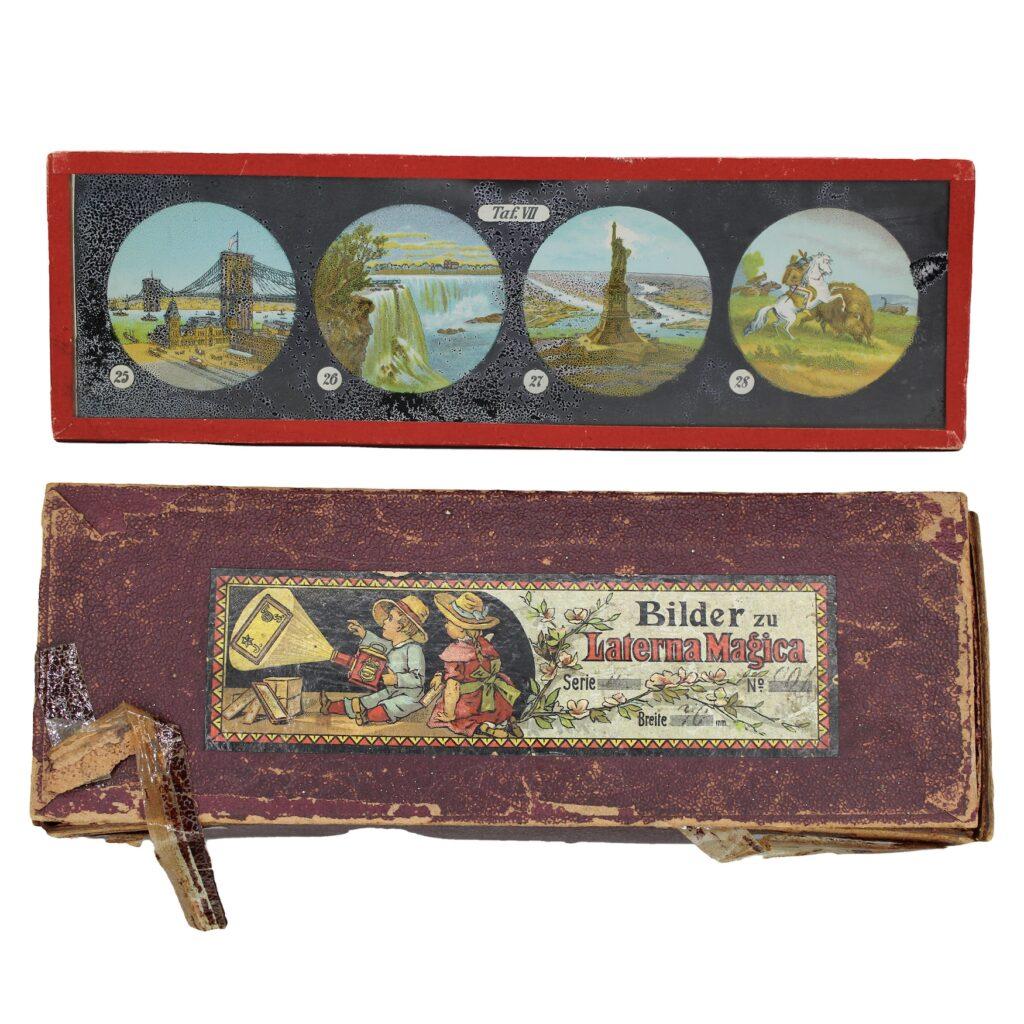

Magic Lantern

By the mid 1800s, well before the invention of photography or movies, magic lanterns and glass slide shows were used to project realistic and fantastical images and were mostly marketed to entertain children. The magic lanterns worked by “a concave mirror behind a flame that directed the light through the glass slide into a lens, projecting the image on a wall.”[11]“The Magic of Lantern Slides,” by Jennifer McCormick, The Charleston Museum.

The slides themselves were a wonder, as “hand-painting slides was a difficult and expensive art, so when a British manufacturing company was able to adapt chromolithography to print colorful illustrations on glass around 1870, illustrated magic lanterns slides began to be mass produced.”[12]“Looking Through the Archives: History and Care of Photographic Slides,” by Michelle Kennedy. A Collections Chronicles Blog, May 25, 2023.

Box of Magic Lantern Slides, n.d. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.074.0070

The Museum has over 100 magic lantern slides in the collections that depict all kinds of images and scenes from New York City, United States and the world at large. These were entertaining to look through and research, especially as it was again unexpected to me to come across so many images with racial stereotypes. One of these slides is on view in the Corner of Curiosities in Maritime City. Go find it in person!

Battleship New York

Battleship “New York,” ca. 1895-1900. Gift of Mrs. Arthur Liman 2002.051.0006

This large wooden pull toy boat, labeled Battleship New York on the stern, is especially unique. Dated ca. 1895–1900, it was manufactured by R. Bliss Manufacturing Company (1832–1914). It measures over 35 inches long and moves on four original wooden wheels. The cardboard and wood ship is covered in sheets of chromolithographed paper, a technique popular at the time for its ability to create multi-colored printed images.

The Museum owns nine similar large wooden ships, all extremely rare, from companies like Reed manufacturing and McLoughlin manufacturing; they reflect “the popularity for toys connected with transportation, as well as a trend for toy manufacturers to reflect real-world technology in their products, including those connected with warfare.”[13]“U.S.S Philadelphia,” V&A, accessed June 10, 2025. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1223128/uss-philadelphia-toy-ship-r-bliss-manufacturing/

To Be Continued

Over the course of this project, I inventoried 104 objects! This, however, is just a sampling of the highlights. The Museum actually holds over 1,300 toys, games, and puzzles which will be continued to be inventoried and researched in the future. I truly have had so much fun giving these objects the care and research they deserve, so that they may be shared with all of you. Through this project, I got a glimpse of what play was like up to 150 years ago. Now, the fun will be kept alive through preserving these object’s physicality and memory through our work.

Additional Readings and Resources

“The Main Street Pocket Guide to Toys” by William S. Ayres, 1984. Main Street Press.

“A Collector’s Guide to Games and Puzzles” by Caroline G. Goodfellow, 1991. Chartwell Books

“A Guide to the 1768 Reproduction Schooner Sultana,” Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network, Sultana Education Foundation, 2003.

“The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board and Table Games” by Margared Hofer, 2003. Princeton Architectural Press.

References

| ↑1 | This includes removing unwanted, duplicate, or incorrect data to improve the quality and reliability of the database. This process, also known as data cleaning, involves identifying and correcting errors, inconsistencies, or missing information. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Instead of relying on paper, most museums use cloud based collections management software, or databases, to keep track of their collections and related information. They can be customized to an institution’s specific needs, and streamline internal research. |

| ↑3 | ”Museums have tried many numbering systems over the years. The most important thing about a number, whether permanent or temporary, is that it be unique because it is the link between the object and its documentation. Without a unique number an object is at risk of losing its context and information relating to its legal status.” 5A, Numbering, Collections Management by John B. Simmons and Toni M. Kiser. Museum Registration Methods, Sixth Edition. |

| ↑4 | A schooner is a type of sailing vessel, originating in the late 17th century, defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. “What’s a Schooner?,” The Great Chesapeake Bay Schooner race. |

| ↑5 | “A Guide to the 1768 Reproduction Schooner Sultana,” Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network, Sultana Education Foundation, 2003. |

| ↑6 | Accession files, or records about objects in a collection, “are maintained on an ongoing basis for permanent reference.” The files include “primary sources of information about the object.” 4A, Types of Files, Collections Management by John B. Simmons and Toni M. Kiser. Museum Registration Methods, Fifth Edition. |

| ↑7 | “Toys as History: Ethnic Images and Cultural Change – Scholarly Essays – Jim Crow Museum.” by Pamela Nelson. Jim Crow Museum. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/links/essays/toys.htm. |

| ↑8 | To learn more about the term “Alligator Bait” and its presence in 20th century American media, read the May 2013 “Alligator Bait” blog post from the Jim Crow Museum: https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/question/2013/may.htm |

| ↑9 | “What Can a Toy Tell Us About Race?” by Eric Feingold, March 15. 2021. |

| ↑10 | ”Brief History of the McLoughlin Brothers” by Laura Wasowicz. American Antiquarian Society, 2003. |

| ↑11 | “The Magic of Lantern Slides,” by Jennifer McCormick, The Charleston Museum. |

| ↑12 | “Looking Through the Archives: History and Care of Photographic Slides,” by Michelle Kennedy. A Collections Chronicles Blog, May 25, 2023. |

| ↑13 | “U.S.S Philadelphia,” V&A, accessed June 10, 2025. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1223128/uss-philadelphia-toy-ship-r-bliss-manufacturing/ |