Examining bindings in the Rare Book Collection

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Manager of Collections Information and Bailey Keen, Collections and Archives Intern

October 27, 2022

Books can be sources of information, connection, and comfort— but how often do you think about how a book is physically put together? Though books are familiar objects, they can also be complex from a material perspective; delicate stacks of paper are sewn or glued together and then sandwiched between protective covers. Not only can books be made from a composite of materials (different papers, ink, leather, cloth, adhesive, chord, wood, cardboard, etc.), but they are objects that are meant to be handled often. A book in use is in constant motion as a reader thumbs through the pages. The pages must be attached in a way that is flexible enough to turn, but stiff enough so that the pages don’t collapse when stored upright on a shelf. All in all, books are an incredibly evolved technology for storing and transmitting communication.

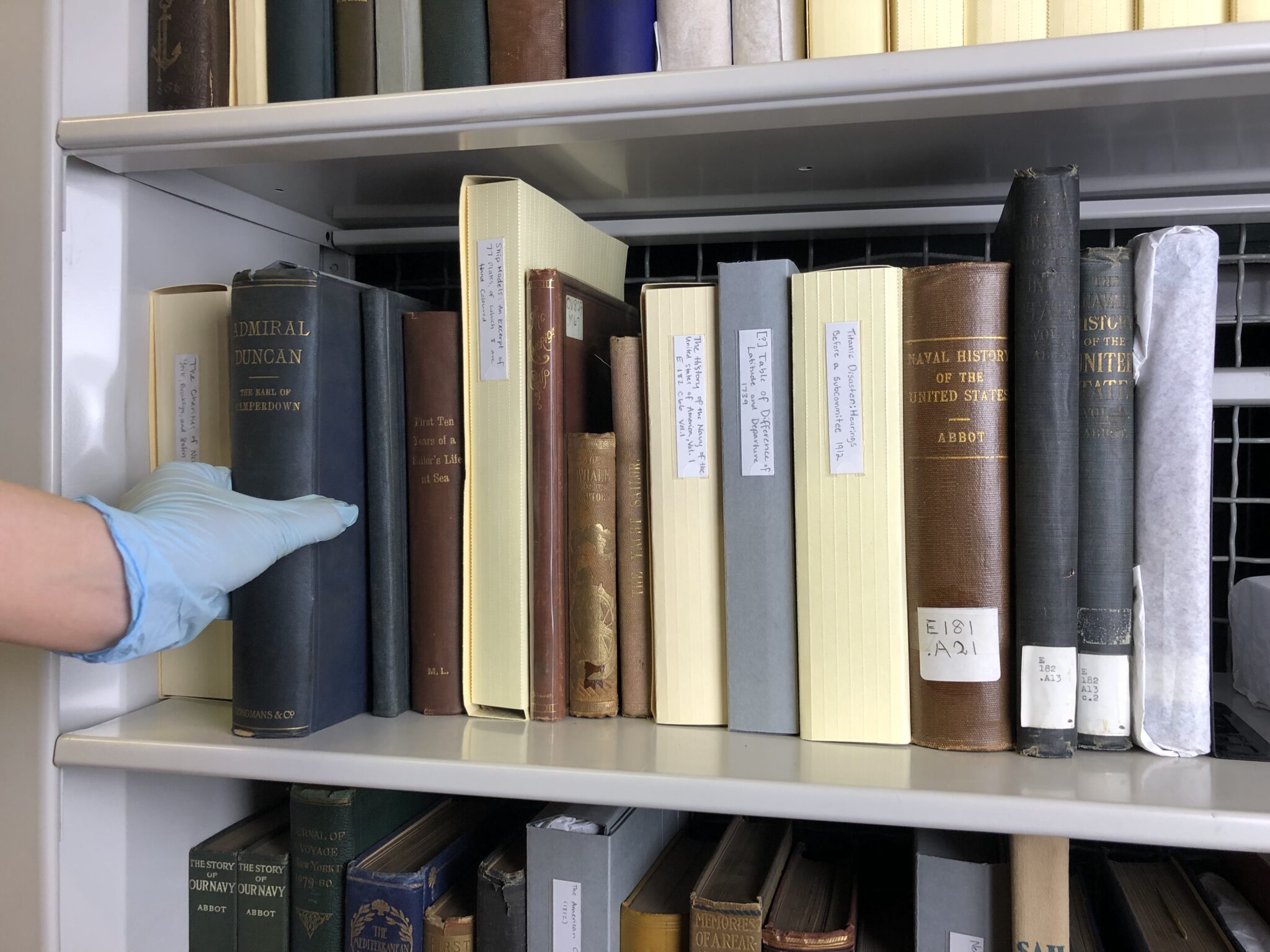

Since 2019, the South Street Seaport Museum’s Collections Department has been inventorying, unpacking, and re-shelving the Museum’s Rare Book Collection after it was moved into the main collections storage. Before the COVID-19 pandemic put the project on pause, the inventory was largely tackled by graduate student Collections interns, with nearly half of the 1,000 volumes already cataloged and condition assessed. This Fall we’ve been able to have fully on-site internships once more, and have resumed work. Though earlier this year I wrote a blog post on what the Rare Book Collection can tell us about sailor literacy and literature in the 19th century, being able to continue the inventory project with Bailey Keen, our Collections and Archives Intern, seemed like a great moment to share more about the work we do to preserve these objects. A large part of the project is documenting the condition of each book and determining whether it can be shelved, whether it needs some sort of extra support, or even if it is best returned to a box for further preservation down the road. As Bailey explains, a book’s binding is the biggest clue:

The first thing I look at when assessing the condition of these books is the quality of the binding. This means I look at how the book physically looks, if I can tell it is falling apart just from using my eyes I know already the book will require extra effort. Aside from using my eyes, when the book is held and opened I need to assess and feel if the bindings are still intact. Some of the most common issues I have found on the books within the Museum’s rare book collection include weak hinges, shedding leather, general discoloration, and even red rot in the worst cases.

Below is a brief, and non-exhaustive, look at the anatomy of a book, a few of the preservation issues that Bailey and I come across in the Rare Book Collection, as well as a couple of our favorite bindings. Though you may not have over a thousand 18th and 19th century volumes in your home, taking a second look at how your favorite books are constructed can reveal fun surprises in the everyday objects we hold in our hands.

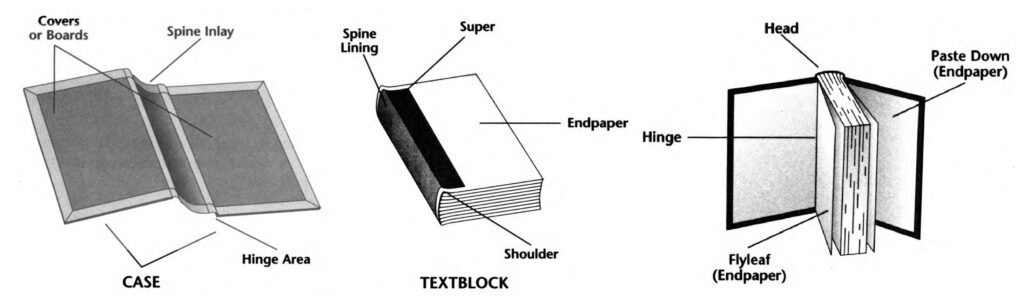

Anatomy of a book

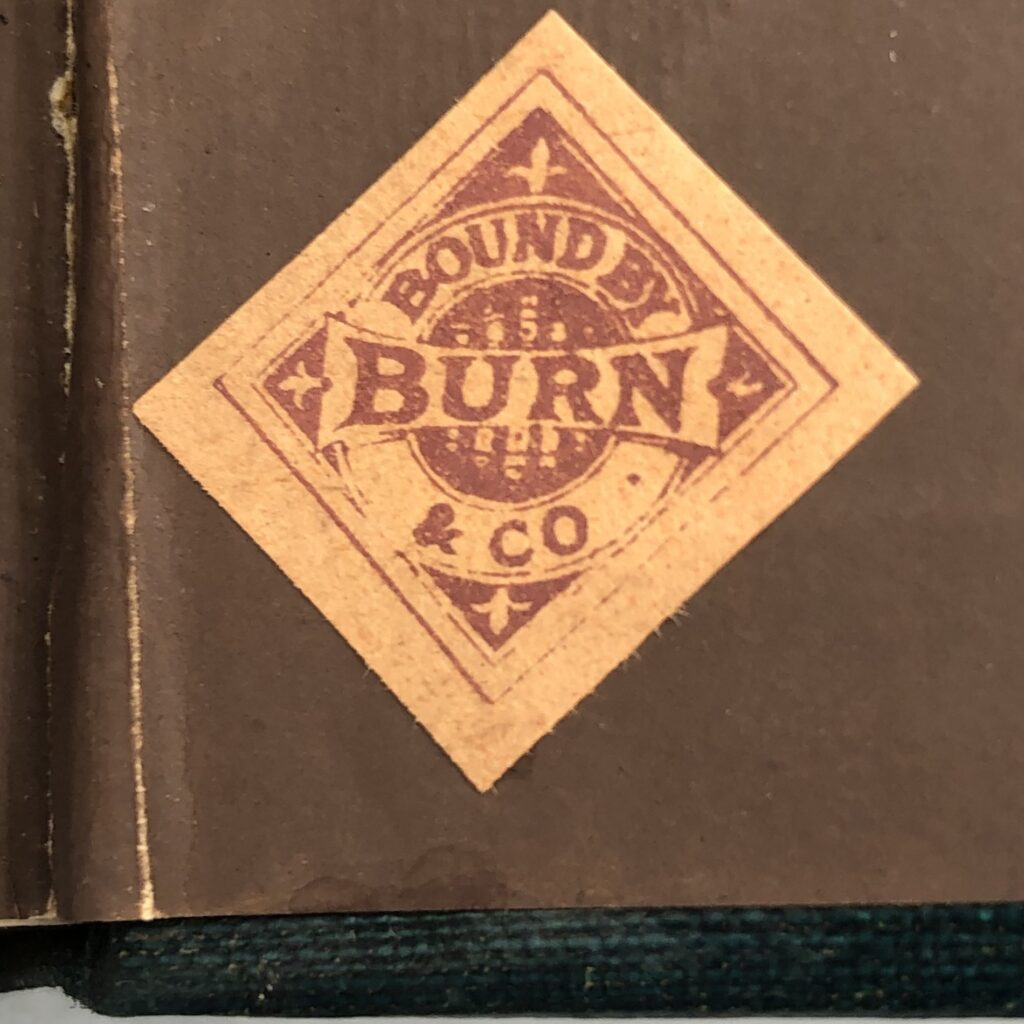

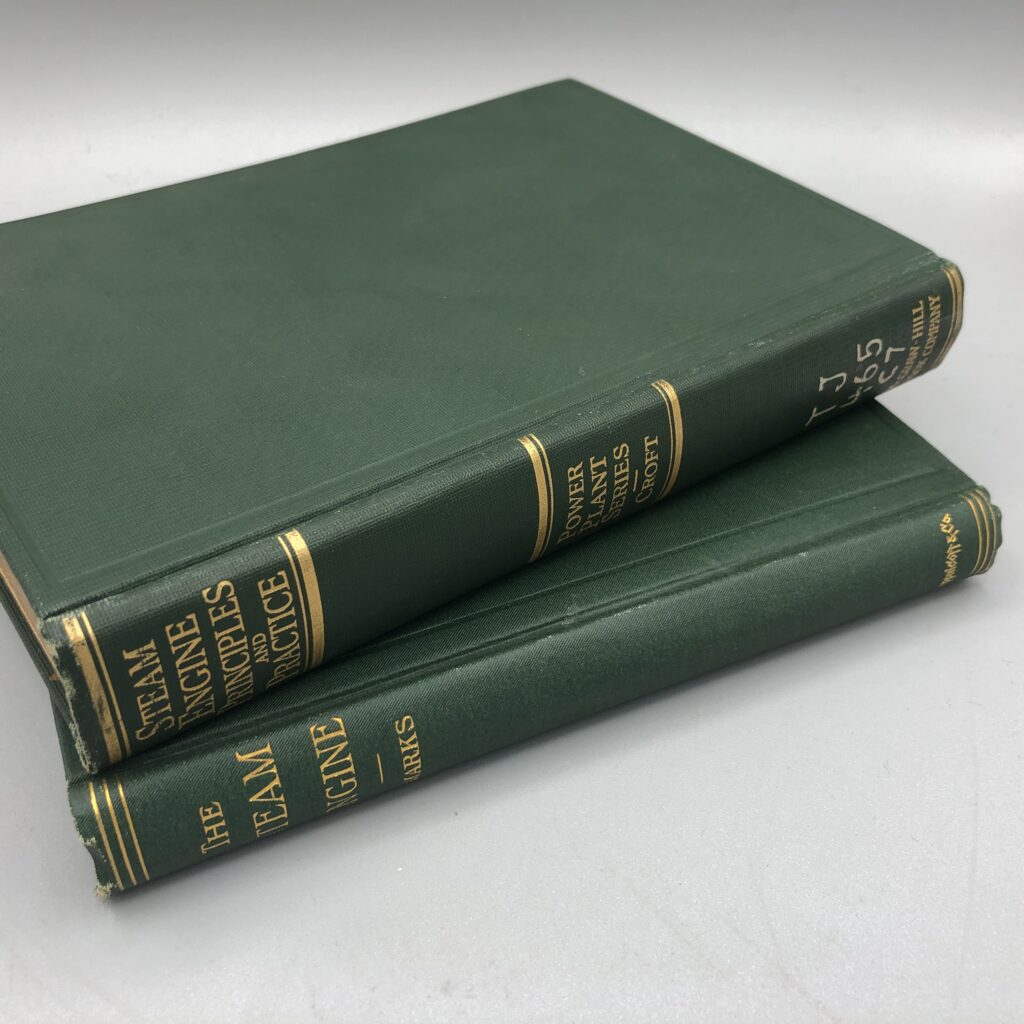

The way books are bound, and the materials used in that process, vary across time and cultures.There are stab bindings, perfect bindings, coptic bindings, and case bindings as just a few of the largest categories, each with their own reasons and place for development and use. Experts in rare books and bindings can discern a lot from an original bookbinding, with stitch-work and decorative elements being used to date and trace a book’s history.

The majority of the books in the Museum’s Rare Book Collection were produced in the United States or Great Britain in the late 18th through early 20th centuries so the examples in this post are largely drawn from this context.

Being familiar with the time and place where an object was produced can be invaluable for collections care, since it gives us a baseline of expected materials, techniques, and preservation issues. This background also makes it easier to find case studies and resources made by other collections professionals and conservators working with similar artifacts. At the very least, it opens the door for using a shared vocabulary.

Excerpt from Gaylord preservation pathfinder :no. 4, an introduction to book repair by Gaylord Bros., 1995

The diagram above describes the elements found in most of the books in the Rare Book collection. The two main components are the text block, which are the gathered together pages, and the binding which surrounds them. Thinking of these as two separate pieces is one of the best ways to understand where stress acts on a book. When a book is upright on a shelf, the text block is dragging downwards on binding, which should be mitigated by the pressure of the books on either side of it. If the book isn’t supported on either side it may slump and distort the text block, but if a book is too tightly packed on a shelf the covers can be abraded when it is removed, or pieces of the spine can weaken as the reader tries to get a grip to pull it out. The sensitivity of books to the proper amount of pressure keeping it upright is why Bailey and I use so many bookends—we can’t have books leaning as we work to fill a shelf.

This leads to one of the most common causes of damage to books: improper removal from shelves.

When grabbing a book, it’s intuitive for a reader to place their hand at the top and hook their finger onto the top of the spine and pull downwards. This causes the book to tilt on the spine’s lower edge, giving the reader enough of the book to grasp the covers. Unfortunately, this stresses the spine and many books show abraded edges or missing pieces at the top of the spine due to this removal method.

When Bailey or I pull a book from the shelf, we gently push the two volumes on either side inwards toward the back of the shelf. This exposes enough of the book to grab it gently from the middle on the boards.

Since we’ve gotten the ball rolling on potential issues, let’s look at a few more:

Arsenic, spines and red rot, oh my!

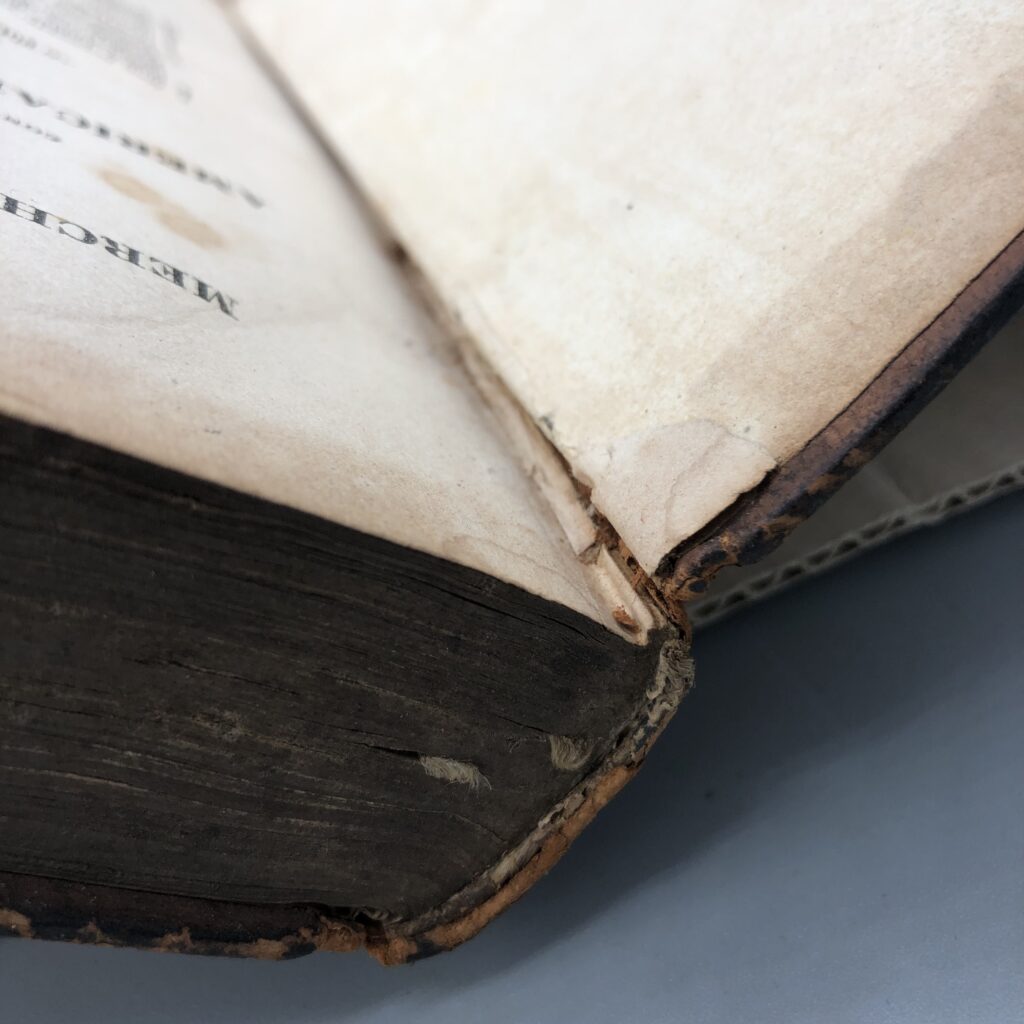

Weak Hinges – The weakest part of a book binding is the hinges, the place where the spine and covers meet. This makes sense since this is the part of the binding that needs to bend when a book is opened and read, as well as the place where the stress of the text block pulls on the binding as a whole. Loose hinges can progress to torn hinges, which would lead to the covers detaching completely.

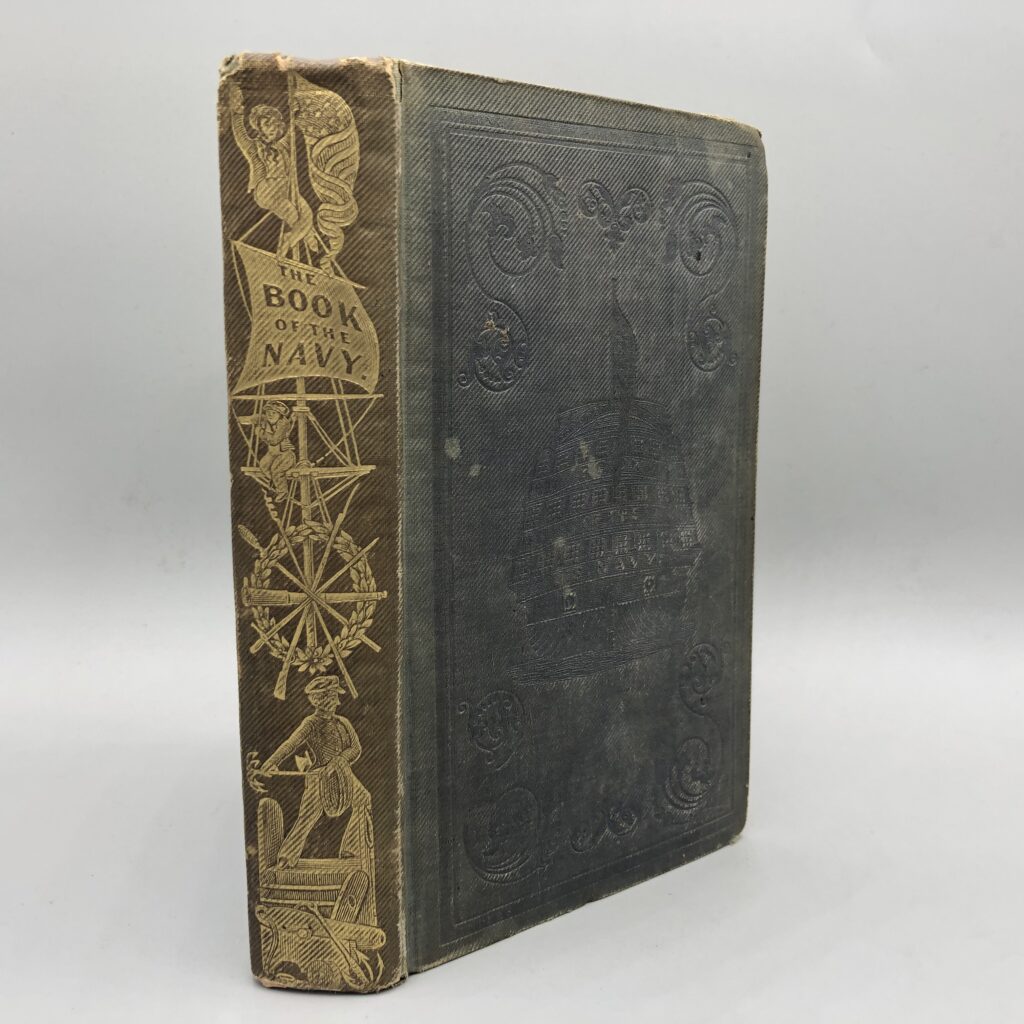

Discoloration – When on a shelf, the spine of a book is facing outwards, and is the only part of a book visible to someone looking at the bookcase. This also means that it is the part of a binding that is exposed to UV light and to air flow. Light can cause paper, dyed cloth, and leather to fade and eventually deteriorate. Air flow isn’t a bad thing on its own, but air can carry moisture and even pollutants which can initiate or accelerate damage. We often find books where the spine and covers appear to be completely different colors after years of exposure.

Red Rot – Leather is made from animal skins that have been chemically treated to resist decomposition. This process, called tanning, involves using acidic compounds. “Red rot”, though not completely understood, is a breakdown of leather caused by strong acids that could have been introduced during tanning or even absorbed from air pollution decades later. Red rot causes bookbindings to disintegrate into a red-brown powder that, along with being irreversible to the book itself, can damage and stain neighboring books.

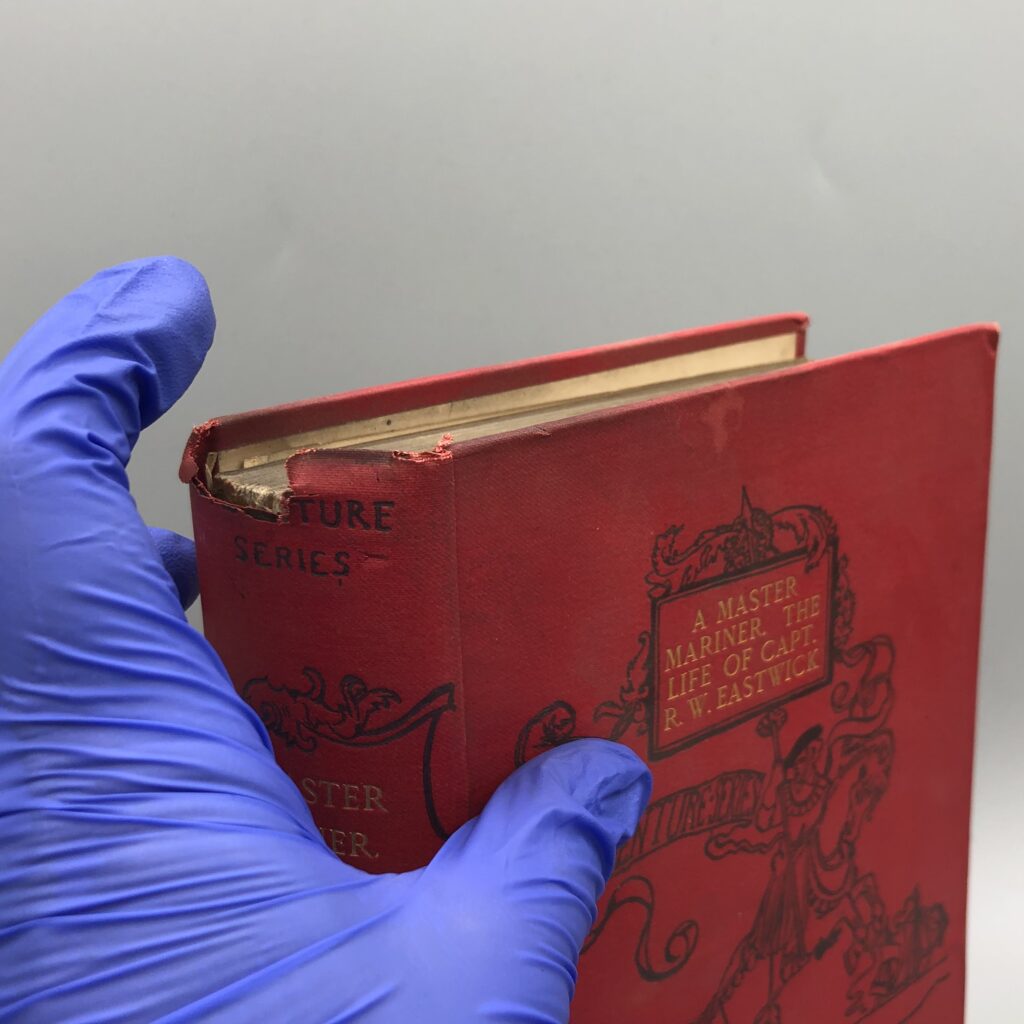

Heavy Metal Dyes – Did you know that book bindings can even be poisonous? One of the reasons why we wear gloves during our inventory is that colorful cloth used in book bindings were sometimes made with harmful chemical dyes containing toxic heavy metals like lead, chromium, arsenic and mercury. The Winterthur Poison Book Project is an ongoing research project focusing on identifying bookcloths containing these pigments and has created a color swatch bookmark to assist colleagues in other collections.

Taking on the issues

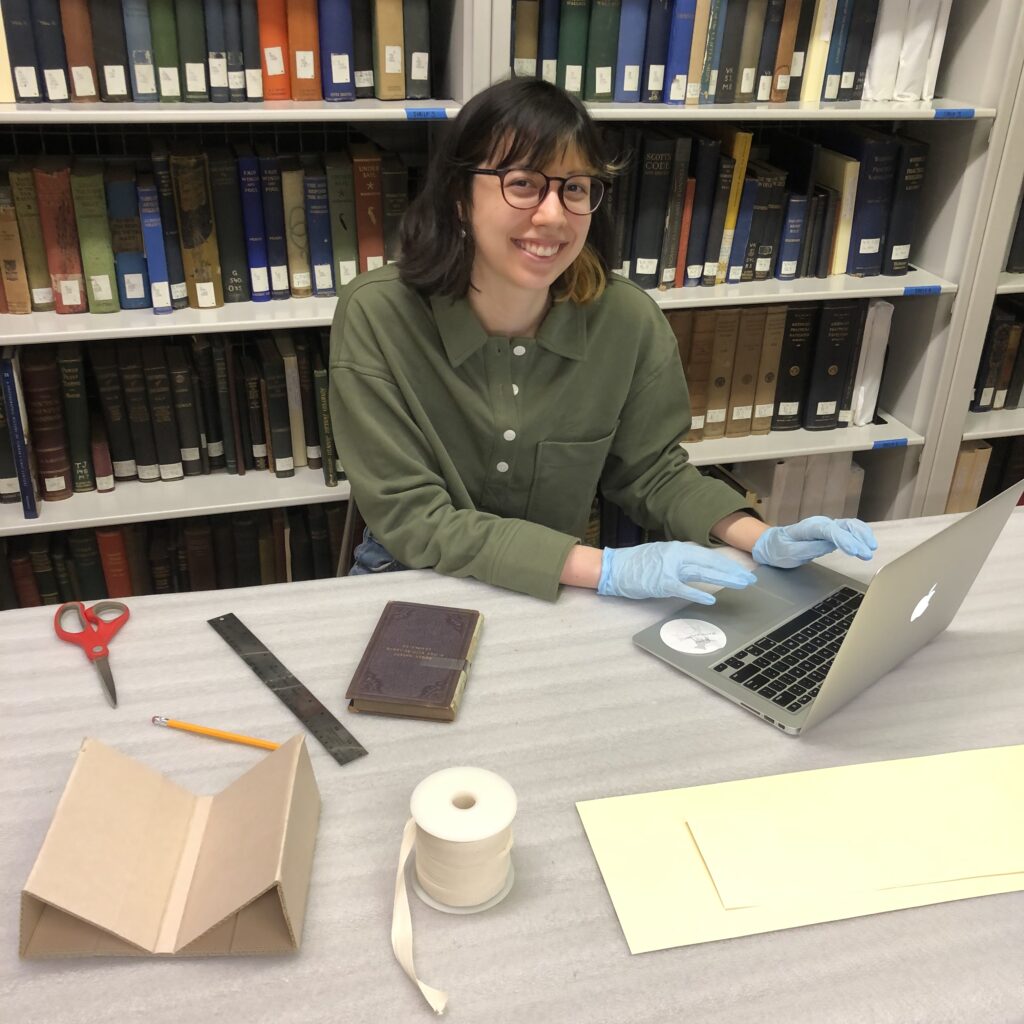

So how do Bailey and I contend with these potential issues? Some are already mitigated by the relocation of the Rare Book Collection to the main collection storage. In a UV light, temperature, and humidity controlled space, these agents of deterioration are carefully monitored. Issues due to improper handling are also mitigated with proper staff training and the protection of nitrile gloves. For the books that are in good enough condition to be shelved, the most pressing decision is whether the book needs the structural support of an external case, or “phase box”. Bailey describes this process below:

If the book gives resistance when I open the front cover I can be confident that the book will not need more preservation efforts and can be placed on the shelf on its own. However, book hinges can get very weak and sometimes completely disconnect the cover and spine. More often than not however, since we are not planning to put these books back to frequent use, if the hinges are attached and the book is able to stand on a shelf on its own we typically decide to shelf these books without a phase box. However, if a binding is weak but not falling apart we take the time to build a phase box, since these books just need the extra pressure to keep its integrity.

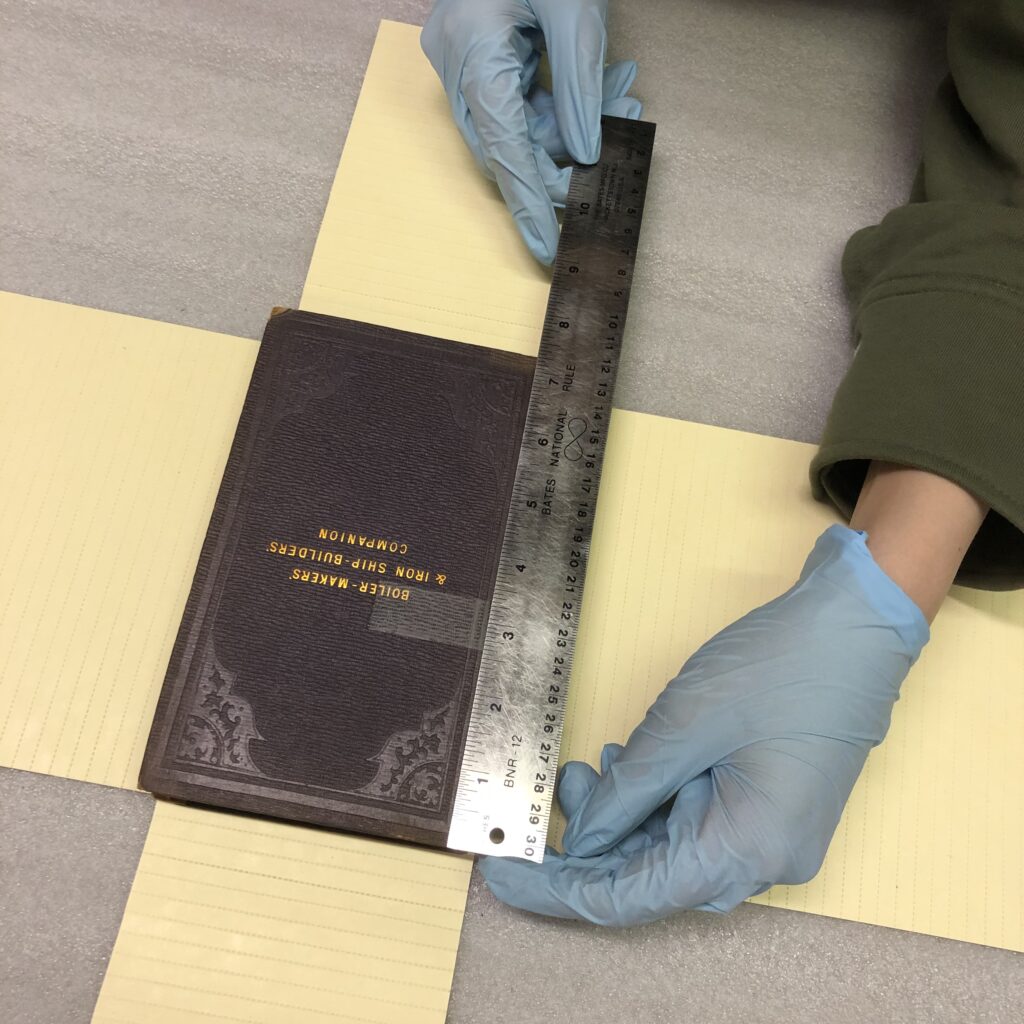

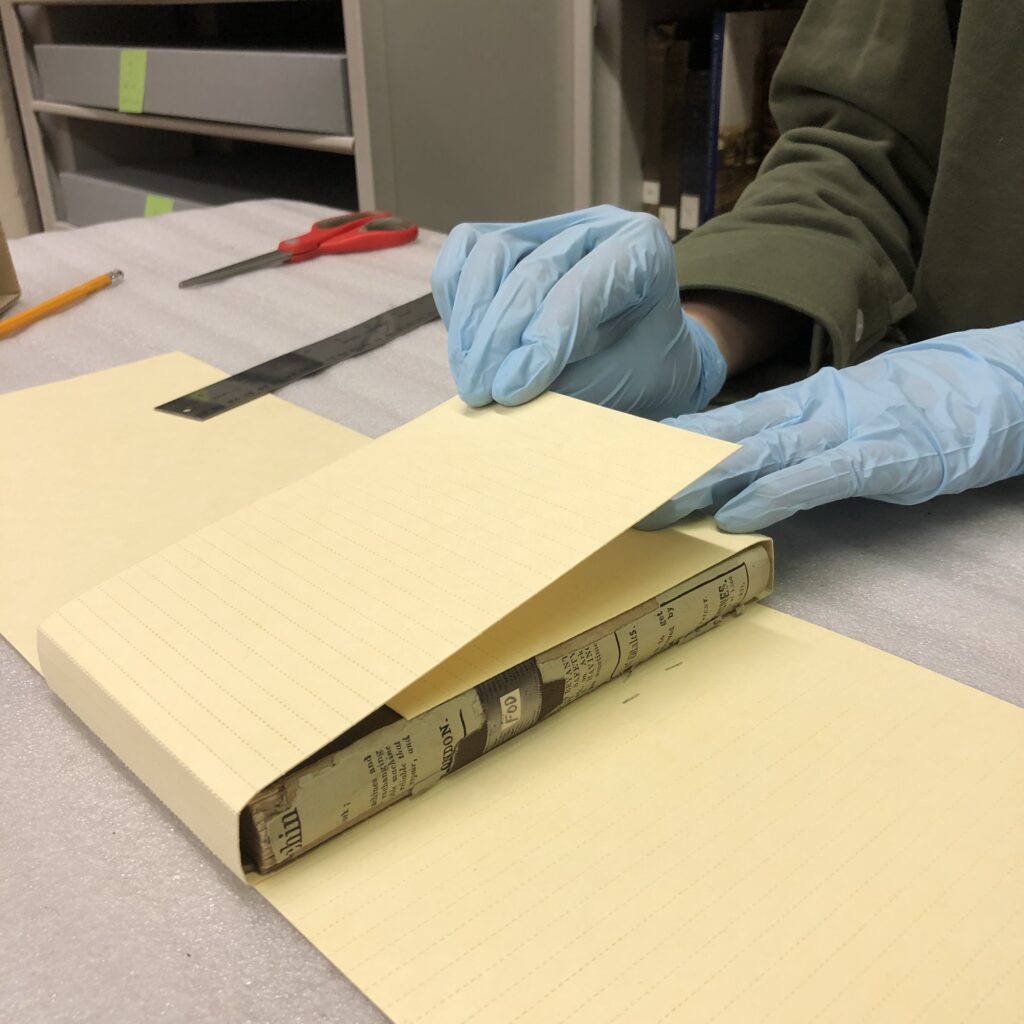

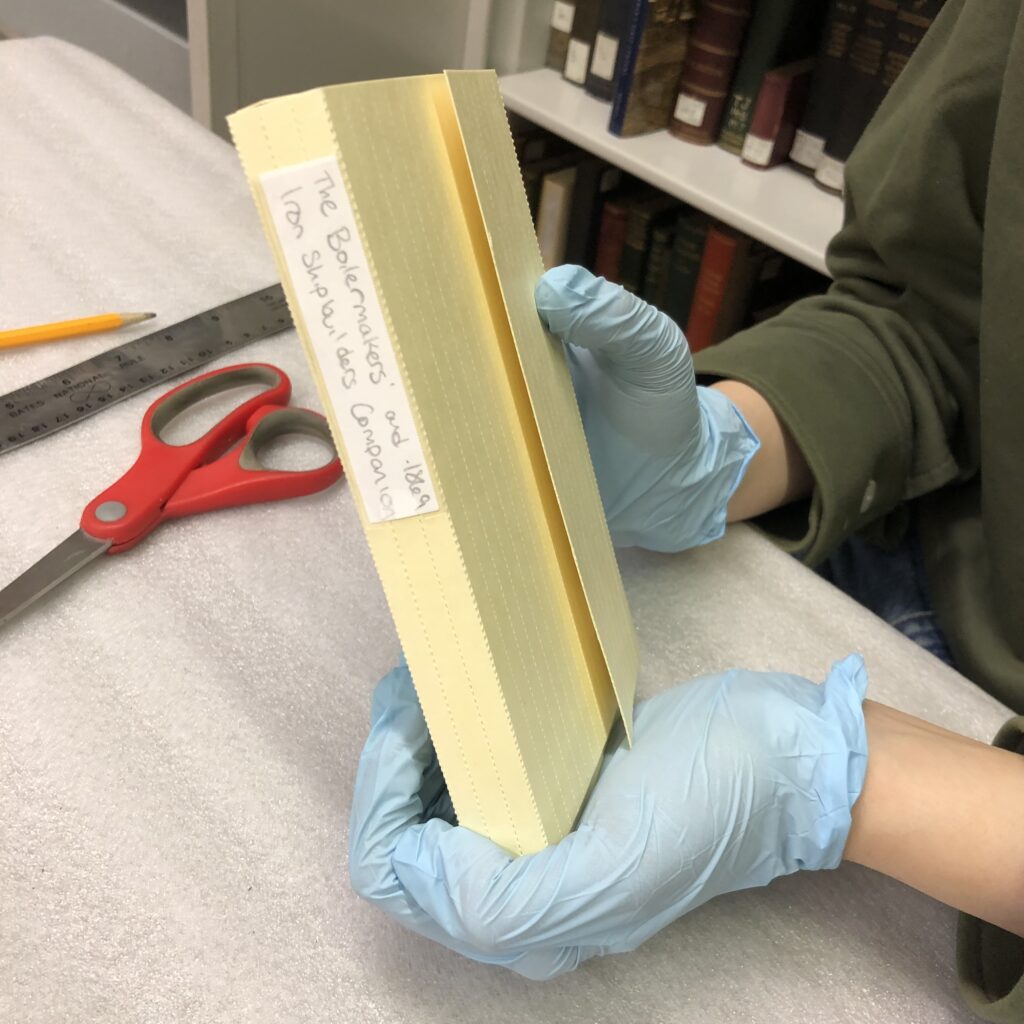

When building a phase box the first thing I do is find the appropriately sized paper. Phase boxes are made with two separate sheets of acid-free paper, one laid vertical and the other horizontal. This means measuring the book and oftentimes trimming down the paper to the exact length and width of the book. The phase boxes we use have small perforated lines in them which allow the paper to be bent to hug the book while remaining sturdy where they aren’t bent. We bend the paper along these lines to hug the book as snug as possible. The vertical piece is done first, and the horizontal piece second. The horizontal piece is then fastened with two velcro pieces, attached to the inside flap and pulled tight around the book. Because the box covers the spine, we then add a label to the box that has the title, date, and call number if it exists. When finished it should look like the box shown in the third image.

Sometimes we build a phase box for a book that doesn’t have any visible damage, but could be extra susceptible, as well are extra valuable to the Museum.

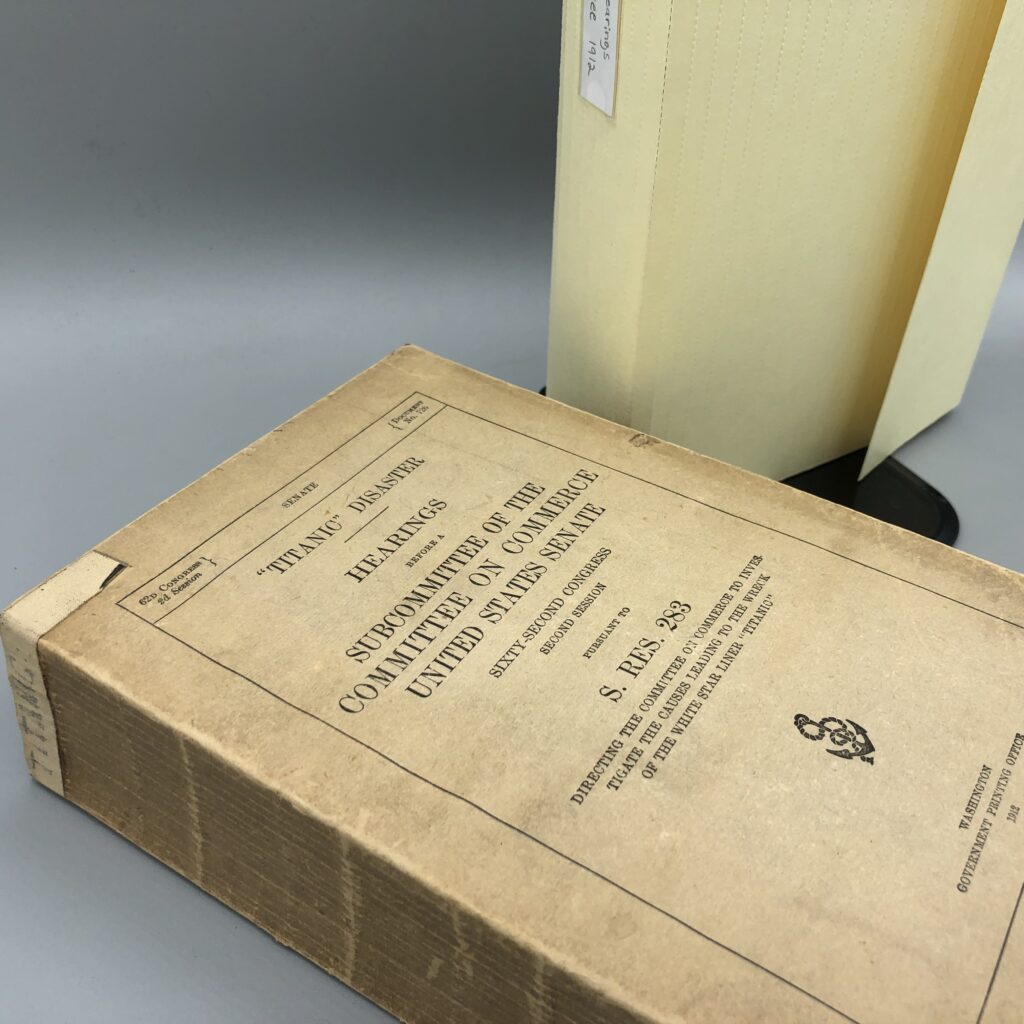

This 1912 “Titanic” Disaster: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate isn’t bound the same way as the case bindings shown in the diagram above. You can see that it is a softcover book that doesn’t have the same protective boards found on most of our other volumes. Though the condition of the binding is good, we’ve still decided to create a phase box to ensure it stays in the best shape possible.

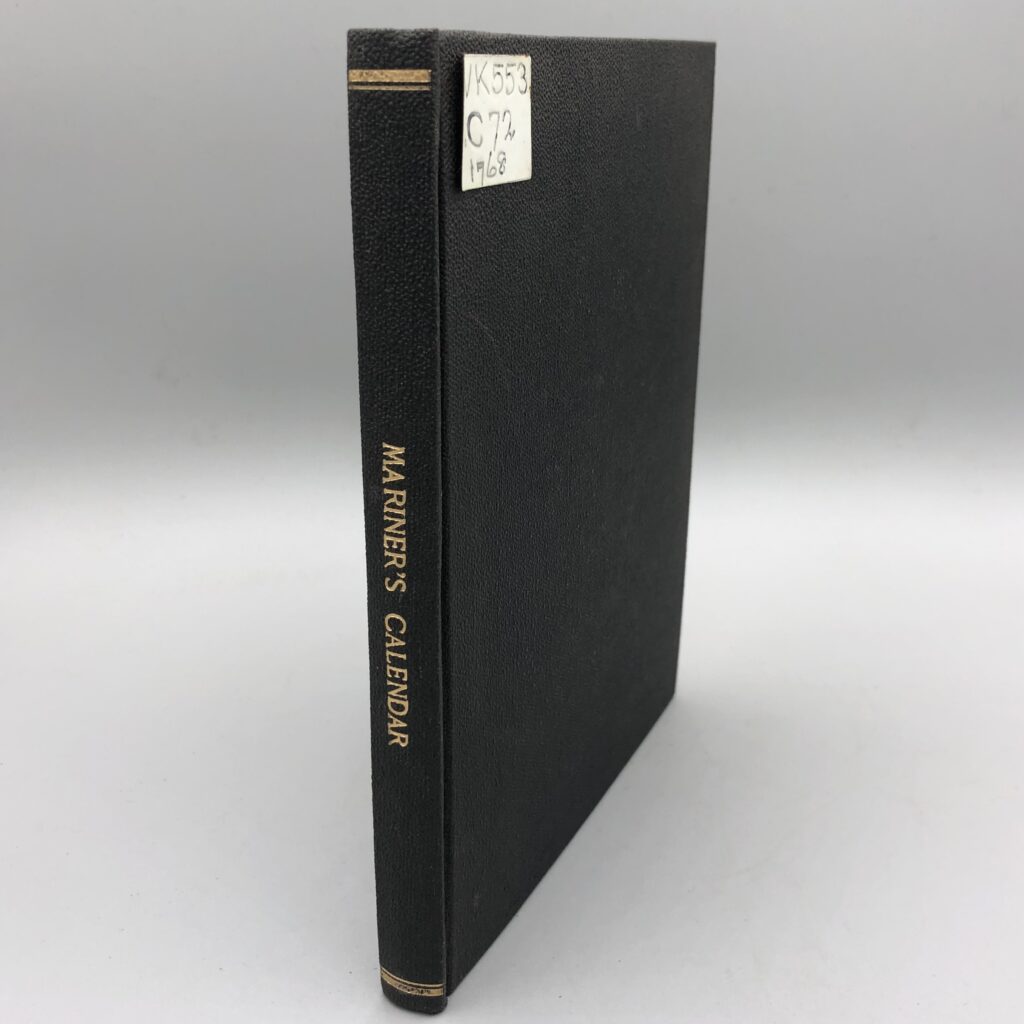

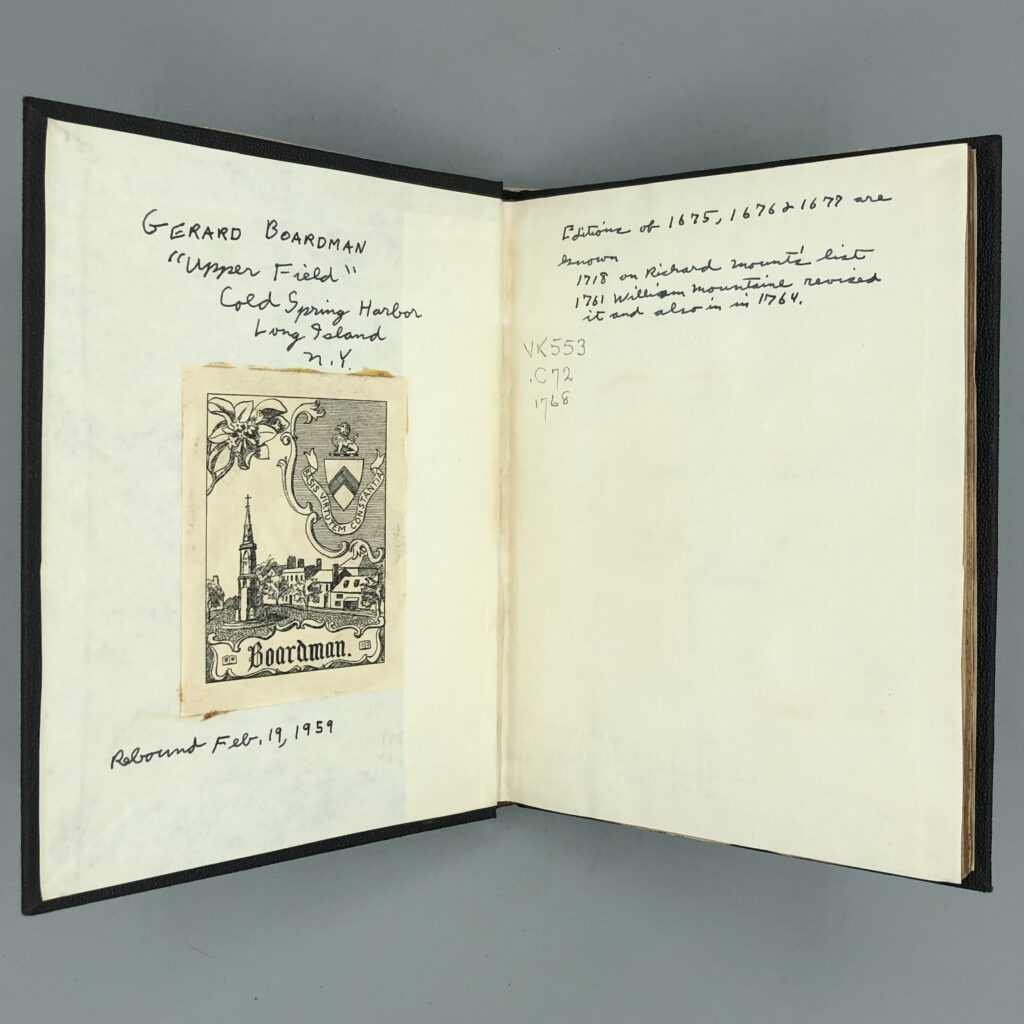

Though our current Rare Books inventory is documenting volumes that need further preservation efforts beyond supportive phase boxes, we are not yet at the point where we are deciding which books could be candidates for rebinding. Many of the books came to the Museum as donations from private collectors or from private libraries that are no longer extant. Though we can appreciate book bindings as artifacts that reflect the time and place they were made, in some situations greater value is placed on the ability for a book to be easily handled, or even “checked out” of a library. In these cases the original binding may be discarded and the textblock rebound in a new binding. The images above show a 1768 book that was rebound in 1959. The new binding is sturdy, and it is possible the original binding was suffering from red rot or another irreversible issue, but the result is a heavily altered artifact. It also goes to show that you can’t “judge a book by its cover” in this collection, since even mid 20th century bindings can hold texts from the 18th century!

A couple amazing bindings

Despite (or maybe because) of all the ways a book’s binding can be damaged or deteriorating, Bailey and I both have a soft spot for some bindings in the collection. Below are just a couple of our favorites:

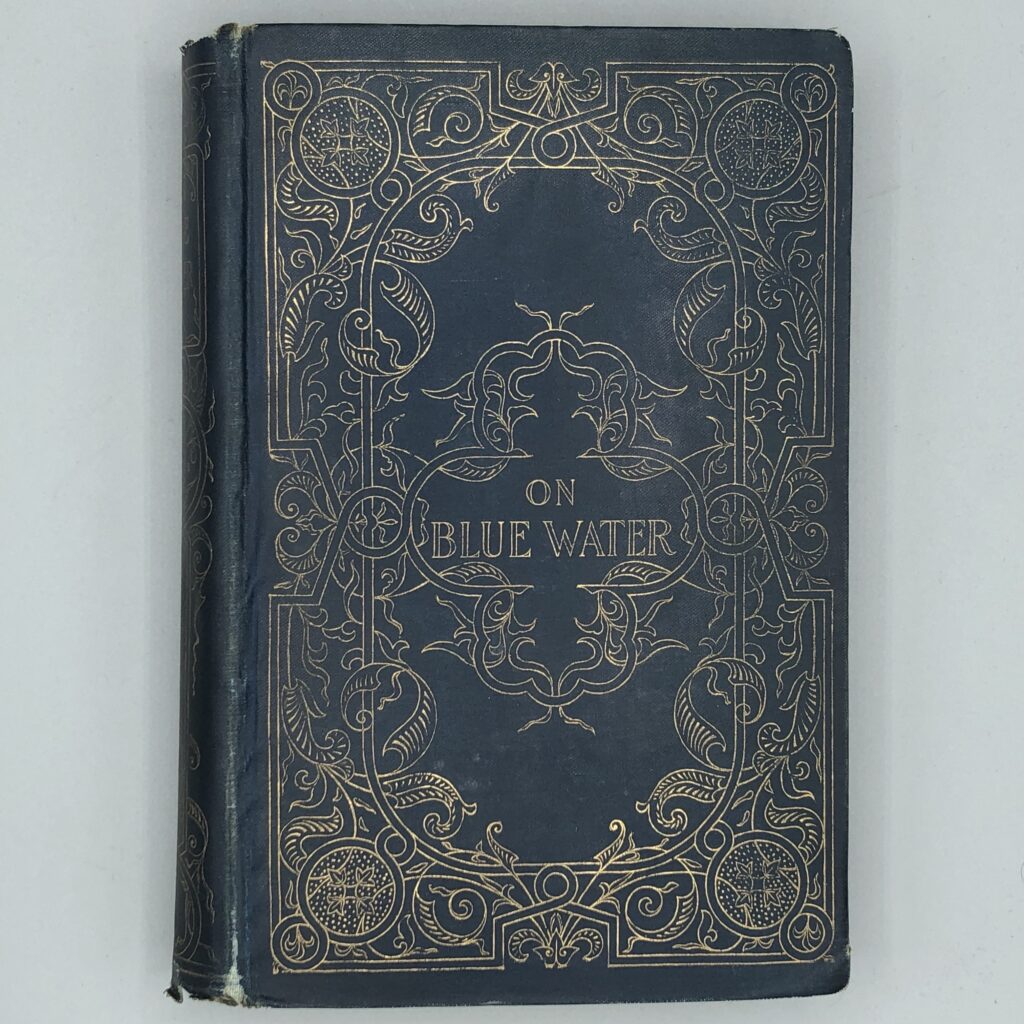

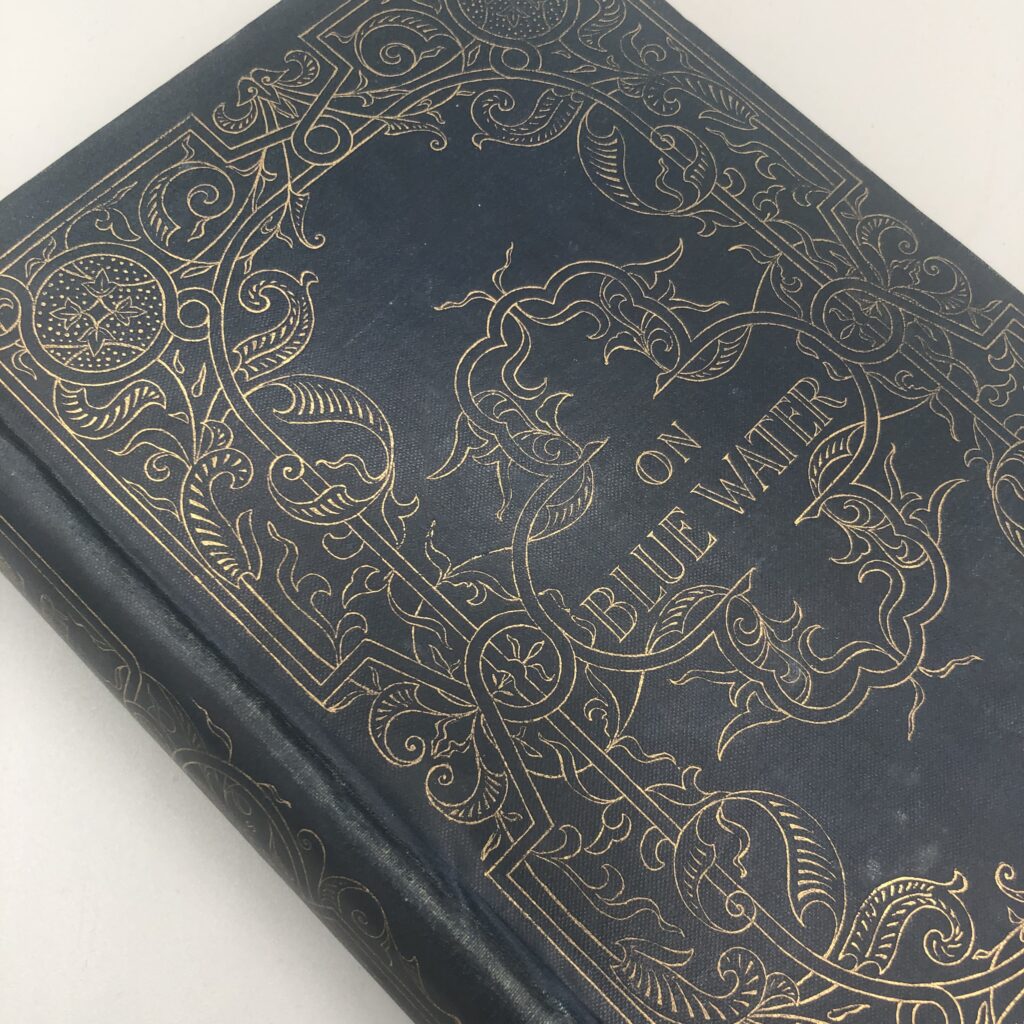

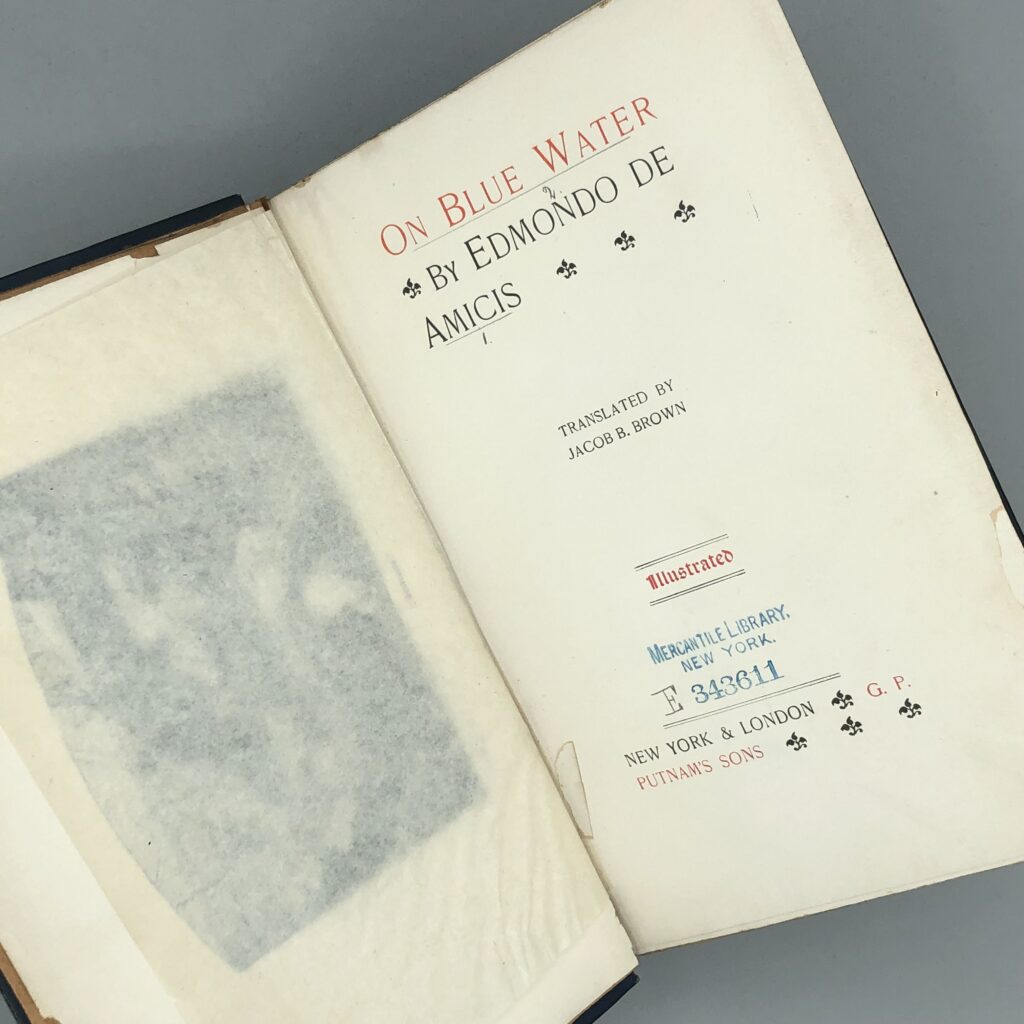

Bailey- Although many of the other books I am working with in this collection are so unique, On Blue Water literally caught my eye with the gold detailing. Edmondo de Amicis’s On Blue Water is bound in blue with gilt edges and designs across the cover, spine, and back. With no publication date, but copyrighted in 1897, this book is in good condition only showing torn hinges with some loose pages. The intricacy and detailing of the gold is beautiful and the lines are still clear and haven’t faded much despite the time that has passed. The gilt on the edges are not as bright as those on the covers, but it’s amazing to imagine what this book once looked like.

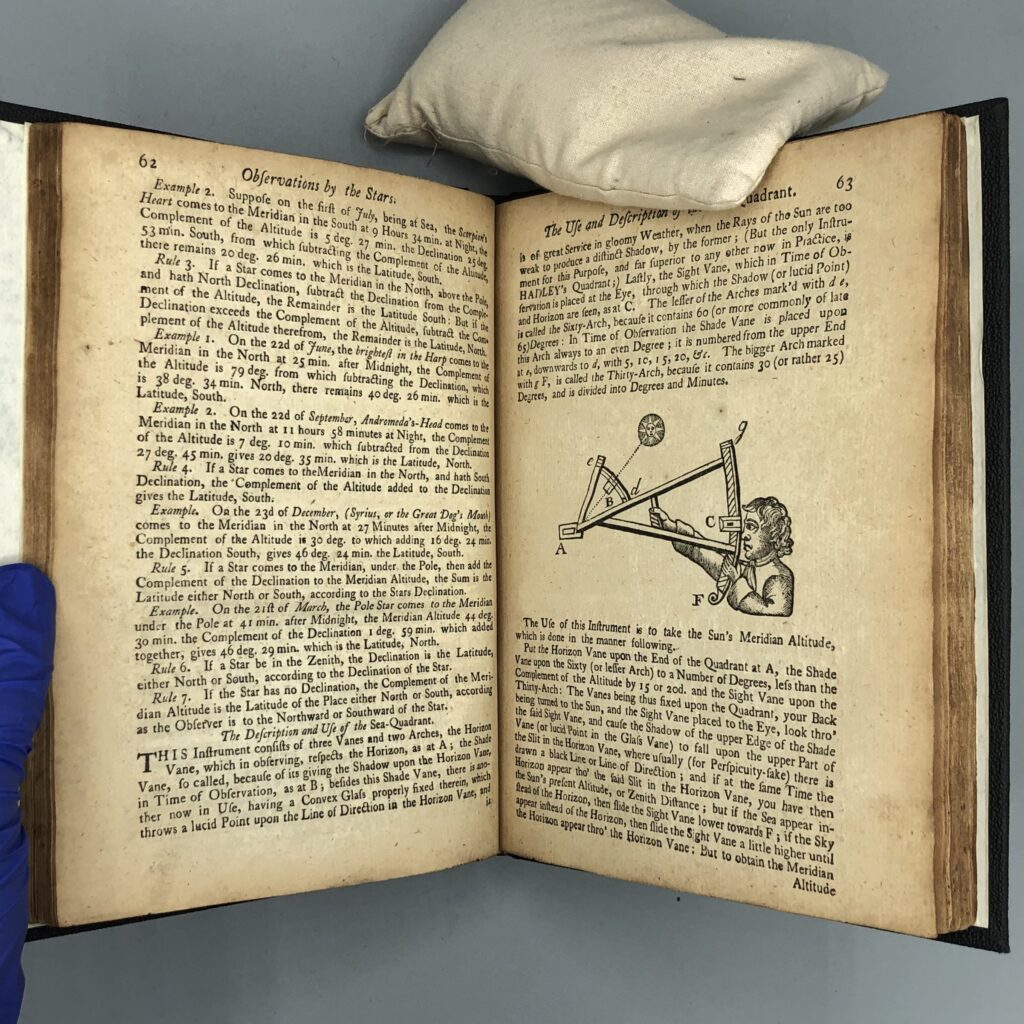

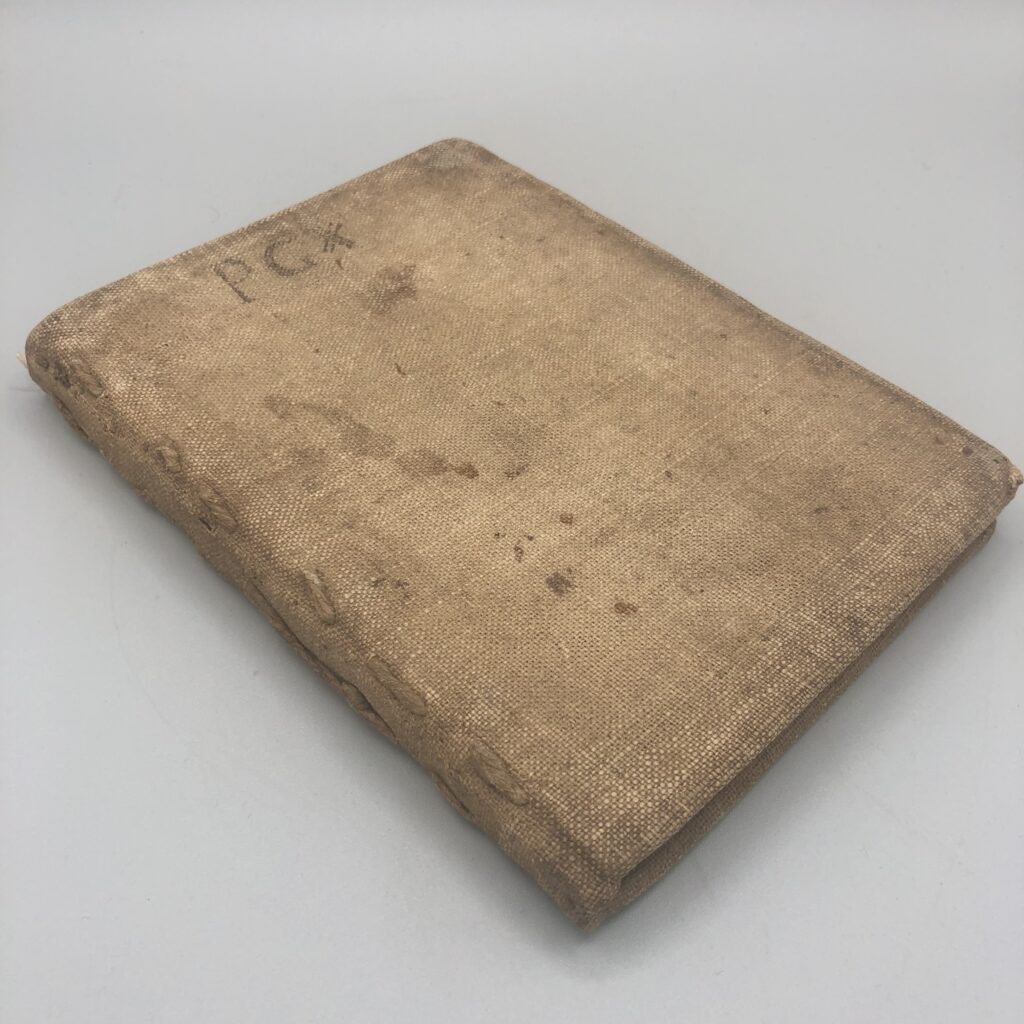

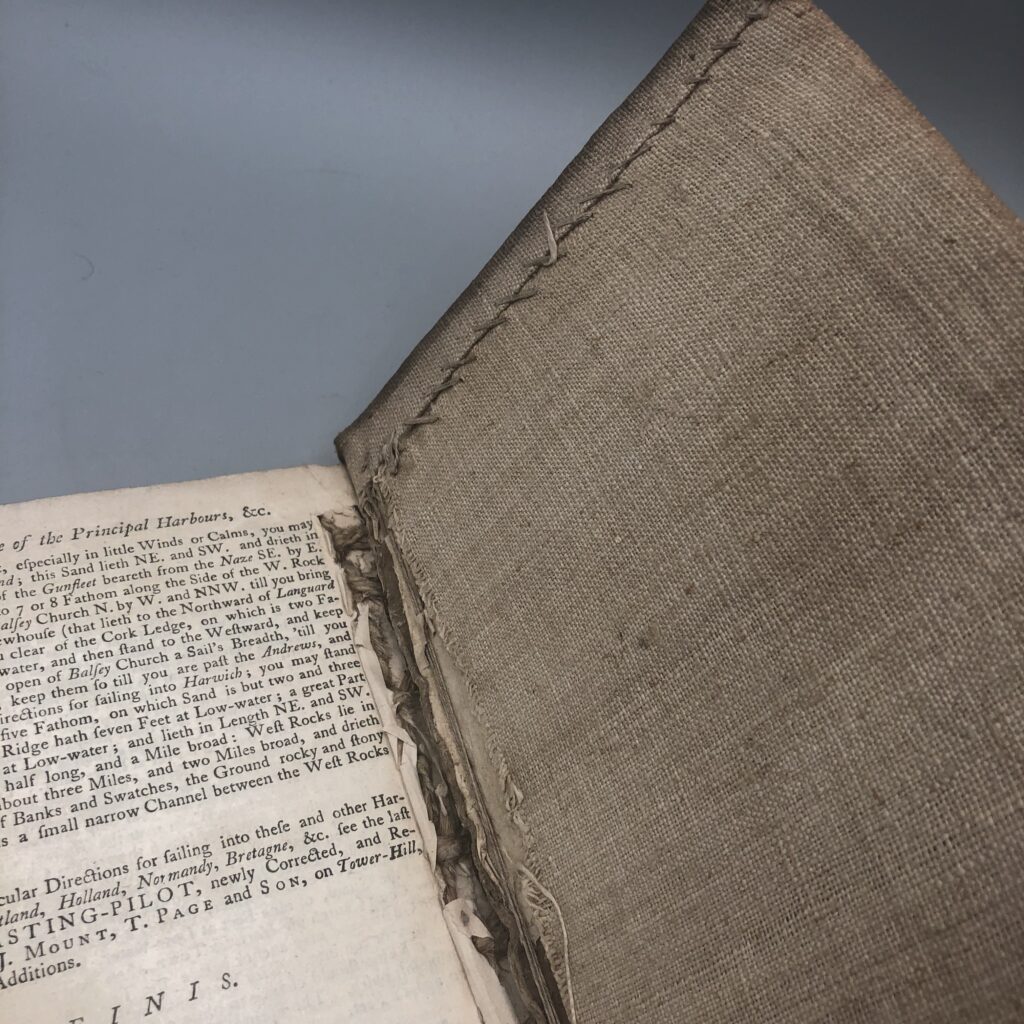

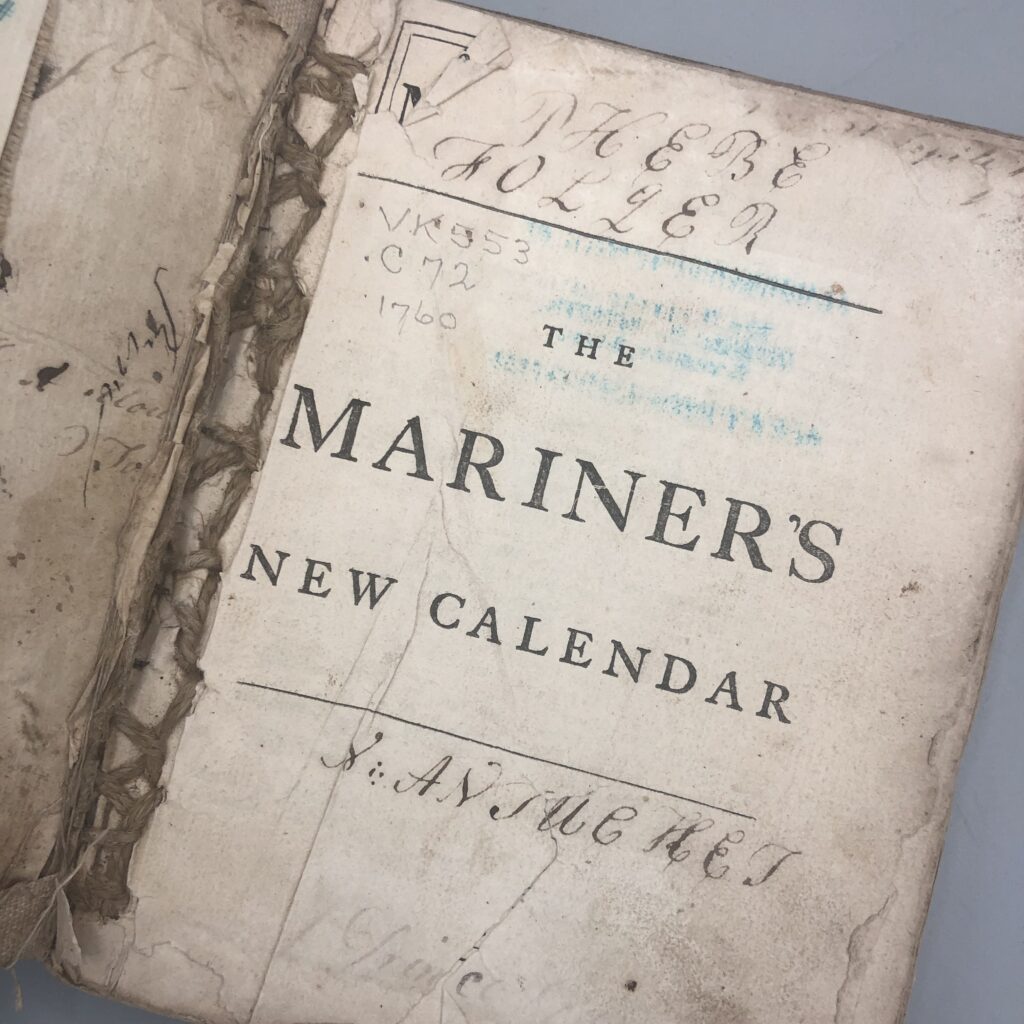

Michelle- The binding for the 1760 edition of The Mariner’s New Calendar by Nathaniel Colson and revised by William Mountaine is different from others I’ve seen in the Rare Book Collection. It was almost certainly rebound by someone who wasn’t a professional bookbinder. The boards are covered in rough canvas. Unlike the diagram of a common case binding shown earlier, where the textblock and binding are largely connected by the pastedown, this textblock is sewn with rough twine directly into the spine. This book is inscribed “Phebe Folger” on the title page and may have been owned by Phebe Folger (1771-1857) of Nantucket, Massachusetts. Though this inscription isn’t technically part of the binding, it would be interesting to see if any other books from her family had similar bindings to compare with this one in our collection.

Additional sources and reading materials

The British Library – Database of Bookbindings, British Library Board. Accessed October 10, 2022.

“The Winterthur Poison Book Project”, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library WikiMedia. Accessed October 11, 2022. Project updates are shared on Instagram through (@winterthurconservation) using the hashtags #PoisonBookProject and #BiblioToxicology.

Book and Paper Group Wiki, Book and Paper Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC). Accessed October 10, 2022.

“Resources on Book Conservation and Preservation”, Northeast Document Conservation Center. Accessed October 11, 2022.

“How to Make a Non-Adhesive Phase Box”, By Jessica Hyslop, West Dean College Arts and Conservation. Posted on 21st September 2015. Accessed October 10, 2022.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.