How Routine Object Cleaning Shines a Light on Brooklyn Waterfront History

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Carley Roche, Collection Preservation Specialist

January 27, 2022

While recently completing routine cleaning and inventory in the Museum’s collection storage areas I came across three beautiful leaded windows.

Leaded glass windows from the Bush Terminal Building, ca. 1905. Wood, lead, glass. Gift of Ellen M. Poler, South Street Seaport Museum 1997.035.0001-.0003

As Collections Preservation Specialist, it is my responsibility to handle the objects in the collection, assess their condition, clean them, and update their information in the Museum’s collection management database. When I saw these objects in storage I immediately noticed they had most likely been untouched for years due to dust and general grime. Carefully using a HEPA filter vacuum to clean away dust on the frames and warm water with a little soap to clean the window panes soon the colors and brilliance of the three windows began to shine once again.

Each window has a unique design: a windmill, a plow, and a sailing boat. While cleaning and working with the three windows, I noticed their similar styles and sizes. I began to research them and found they all belonged to the same building: the original Bush Terminal Building (1905-1961). The objects were salvaged by their donor before the building was demolished and gifted to the Museum in 1997 as a testament to early twentieth century architecture, and the port of New York in its heyday.

The Bush Terminal Company has a long history tied to New York Harbor and the Brooklyn Waterfront. Irving T. Bush (1869-1948), founder of the company, used his family resources and business savvy to create a self-sustaining network between industry and people that can still be found in Brooklyn today.

Founding the Bush Family Business

Rufus T. Bush (1840-1890) co-owned a small oil refinery in today’s Sunset Park, Brooklyn, in the late 1800s. He was known for his loud and public accusations having testified against Standard Oil’s profiteering from railroad rebates.[1] Roger M. Olien & Diana Davids Olien, Oil and Ideology: The Cultural Creation of the American Petroleum Industry (University of North Carolina Press, 200), pp. 60. Apparently there was no true ill will between Rufus and the oil corporation as he sold his land and refinery to Standard Oil in the 1880s. He used his new wealth to buy the schooner yacht Coronet to travel around the world with his family.

After Rufus’ passing in 1890, his adult son, Irving T. Bush, used his inheritance to buy back his father’s former land from Standard Oil. The company had dismantled the refinery and changed the layout to hold six warehouses and a steamship pier. With these new acquisitions, Irving founded Bush Company, a freight-handling terminal working with both sea and rail transport. At the time, rail transportation between Manhattan and Brooklyn was extremely expensive due to railroad companies needing to take freight cars off of railroad tracks, load the cars onto barges, use tugboats to pull the barges across New York Harbor, then finally reload the freights onto tracks in Brooklyn.

It was a time-consuming process that took a lot of manpower, thus costing a lot of money. Nobody questioned Irving’s choice to transport via his port, but ridiculed his plan to include railroads as “Bush’s Folly”[2] Spellen, Suzanne. Walkabout: The Bush’s and Brooklyn’s Industry City, Part 2. June 7, 2012.. Irving proved his aptitude for business when he secured a contract with Baltimore and Ohio Railroad by personally purchasing freights of hay in Michigan and turning a profit through his railways. Soon he began to gain contracts by importing goods through his port and exporting them through his railways. The Bush Company became a roaring success after public scrutiny and doubt.

Industry City

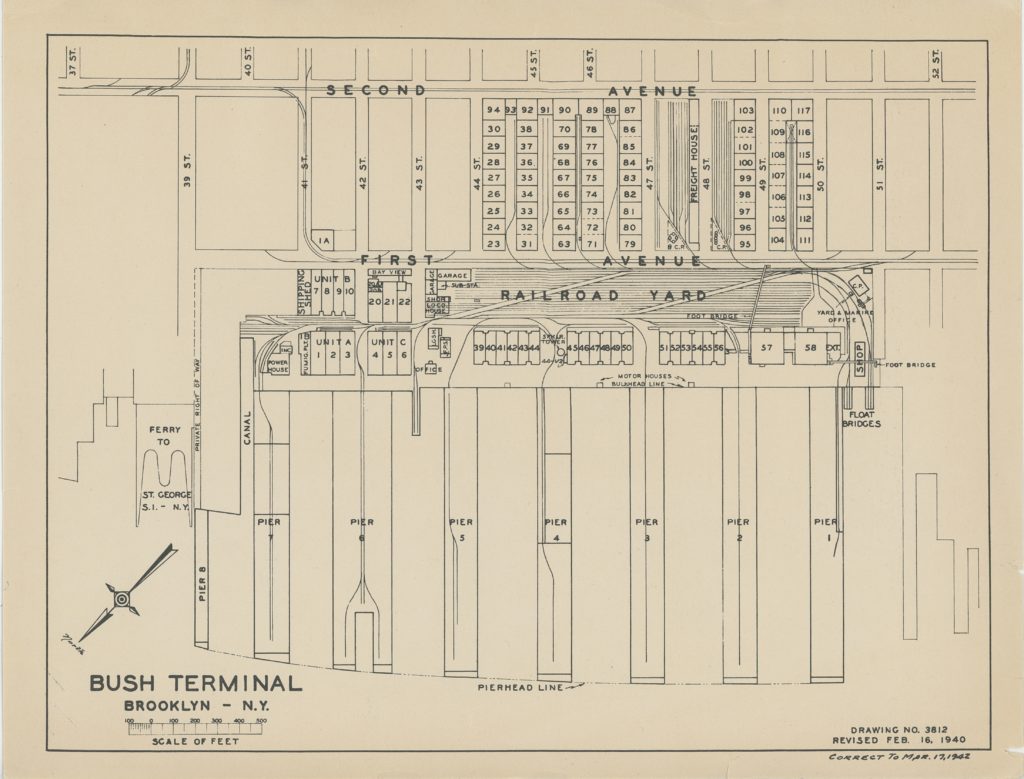

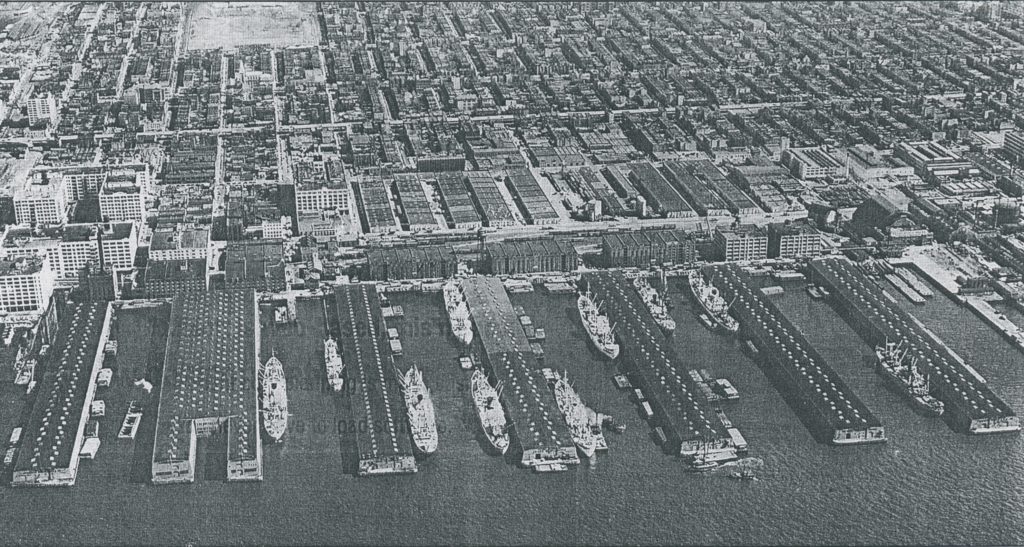

In 1902, Irving changed the name of his business to Bush Terminal Company and bought the land surrounding his original plot. Expanding to 3,100 feet along the Brooklyn Waterfront, Bush Terminal Company owned 120 warehouses; 50,000 railroad freight cars; seven 150-foot enclosed piers; and handled 10% of all steamship traffic in New York Harbor. Recognizing the terminal’s influence over the shipping industry and ideal location, the War Department took over the industrial complex on December 31, 1917 for the duration of World War I. The US Government sent approximately 70% of ammunition, clothing, and food used by American soldiers abroad from Bush Terminal.

Bush Terminal, Drawing No. 3812, ca. 1940-1942. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

At the end of World War I, Bush Terminal Company was the home to approximately 300 companies and 35,000 workers– literally. The now quite large area of land within Brooklyn became its own city including its own courts, police force, and firefighters. Four tribunals handled the cases for employees in different industries: marine, railroad, trucking, and mechanical. All employees, no matter their seniority, held the right to appeal to Irving T. Bush himself at any time. A legislative body, named the Pivot Club, also arose within the city and met twice a week to handle issues from traffic jams to the just treatment of women on the waterfront.

Aerial view of Bush Terminal Company’s Seven Piers, ca. 1940s. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Bush Terminal Building

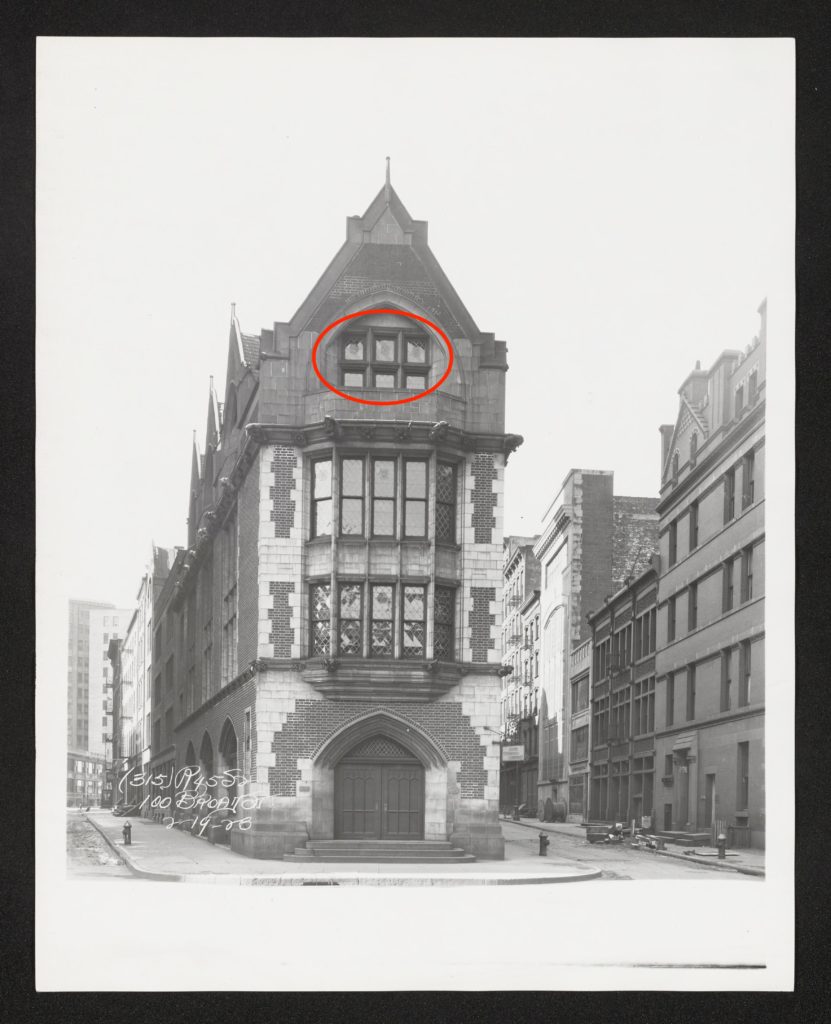

When the Bush Terminal Company began to succeed, Irving T. Bush commissioned the architecture firm Kirby, Petit, & Green to design an office building in Manhattan to serve as the company’s headquarters. Located at 100 Broad Street, once the place where Manhattan’s first Church stood, the new building featured a Gothic-style with gargoyles, leaded windows, and red brick– vastly different from the more modern use of stone and steel that became the norm at the turn of the 20th Century. Influenced by Dutch and English styles, Kirby, Petit, & Green wanted to pay homage to the histories of both Manhattan and the Bush family with this particular design; and it is from this building that our windows come from!

“100 Broad Street, Manhattan” ca. 1890. Courtesy of New-York Historical Society. Copyright Permission by New York Transit Museum.

Marked up is the location of our windows.

After its completion in 1905, the Bush Terminal Building was lauded for its general look however many felt it was not the right design for a building in the heart of Manhattan’s financial district. Looking more like a Jacobean mansion, one writer for Architectural Reader stated it looked “out of place” due to its office building neighbors. He also predicted that the Bush Terminal Building “will become still more conspicuous” with the eventual default to skyscrapers in Manhattan.

Detail view of the leaded window designs. South Street Seaport Museum 1997.035.0001-.0003

Despite the predictions and feelings of impractical designs the Bush Terminal Building on Broad Street stood until 1961. Although Irving moved the official headquarters to a 30-story building in Midtown in 1916, the original Bush Terminal Building rented out its space to various clubs and organizations. Among these included the Jolly Mariner’s Club, the American Institute of Architects, and the Merchants’ Association. The Bush Terminal Company officially sold their original headquarters building in June of 1961 to New York Clearing House. The new owners quickly demolished the Gothic-building to replace it with a completely new modern design.

Conclusion

The economic impact of the Bush Terminal Company cannot be understated. Practically taking over the Brooklyn industrial waterfront, creating a self-serving city for its employees, and managing its business across two boroughs is an impressive feat. With the use of container shipping after World War II, the need for the Bush Terminal Company began to decline. By December 1971, the Bush Terminal Railroad was officially disbanded and the City of New York began to intervene in the handling of the once independent industrial complex. Today, the location is known better as Industry City– a thriving business park home to artists, cultural institutions’ archives and storages, companies, restaurants, and public spaces.

100 Broad Street in 1890 and 2022.

As for 100 Broad Street– the intersection at Broad, Pearl, and Bridge Streets– is now home to towering glass and steel office buildings, bars, and restaurants. The windows in our collection were salvaged after the demolition of the Bush Terminal Building along with several window medallions each with a unique design. Despite New York City’s ever evolving architecture, its past can still be found through small windows of history.

Additional Reading and Resources

“Bush Terminal Building in 42d Street.” Real Estate Records and Buyers’ Guide 97, no. 2509, 1916, p. 589.

“Bush Terminals Taken Over by U.S. as a Supply Base.” New-York Tribune. January 1, 1918.

“Bush Terminal, a City Itself, Governs 35,000 Inhabitants by Own Courts and Lawmakers.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle on December 16, 1928.

Irving T. Bush, “Working with the World” Doubleday, NY, 1928.

Irving T. Bush Obituary, published by The New York Times on October 22, 1948.

Kline, Polly. “Bush Terminal RR Quits; Patrons, Workers Stranded.” Daily News. December 15, 1971.

Olien, Roger M. & Olien, Diana Davids. “Oil and Ideology: The Cultural Creation of the American Petroleum Industry” Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

TRANSFER No. 37, Magazine of the Rail-Marine Information Group, Jan-Apr 2003, p. 3-28.

Spellen, Suzanne. “Walkabout: The Bush’s and Brooklyn’s Industry City, Parts 1-6.” Brownstoner (blog). June 2012.

Miller, Tom. “The Lost Bush Terminal Building – 100 Broad Street.” Daytonian in Manhattan (blog). March 26, 2018.

References

| ↑1 | Roger M. Olien & Diana Davids Olien, Oil and Ideology: The Cultural Creation of the American Petroleum Industry (University of North Carolina Press, 200), pp. 60. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Spellen, Suzanne. Walkabout: The Bush’s and Brooklyn’s Industry City, Part 2. June 7, 2012. |