An overview of menus from passenger ships 1860s to 1960s

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

November 12, 2020

There is something wonderful about sitting down to a meal and picking out a delicious dish from a menu. Though the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has made restaurant dining impossible for many, going out to eat with friends and family will no doubt return as a ubiquitous way to socialize and celebrate milestones.

While waiting for the day we can go back to ordering shared appetizers for the table, let’s look at some historical menus in the South Street Seaport Museum collection. Though the Museum’s collections and archives include menus from New York City establishments, the vast majority are from the galleys, dining saloons, and restaurants on board ships coming to and from New York and other east coast cities. These menus are a sneak peek into over 100 years of ocean-going passenger travel.

Take a look and imagine, if you were sitting down to the ship’s table— what would you order?

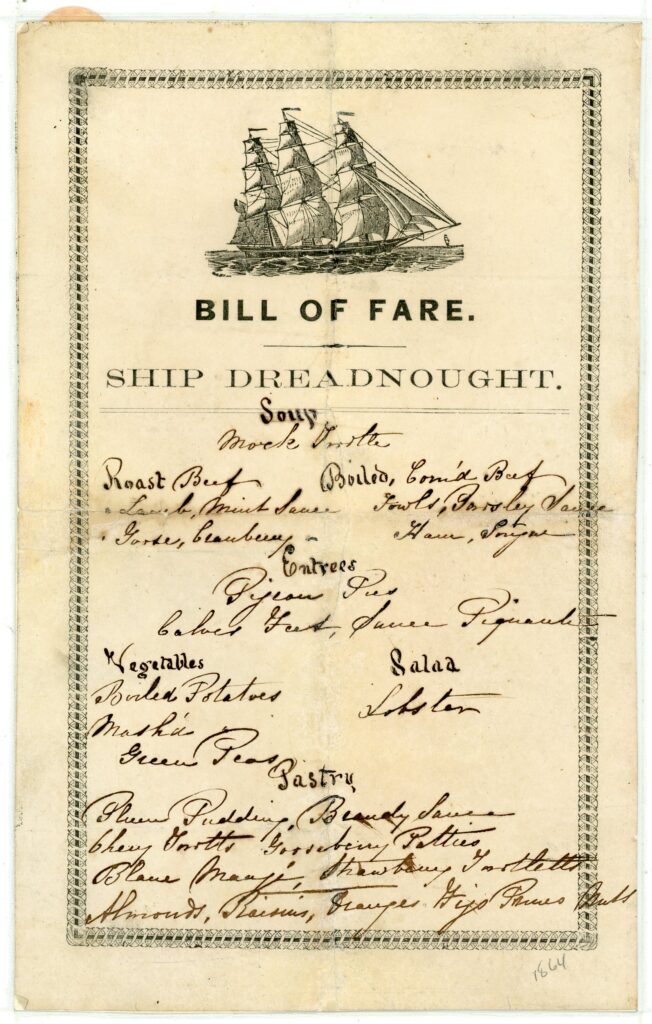

Clipper Ship Dreadnought, Bill of Fare, ca. 1864. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 1991.070.0261

Let’s start with the oldest menu. This ca. 1864 “bill of fare” would’ve been offered to passengers aboard the clipper ship Dreadnought. A three-masted sailing ship built in 1853, Dreadnought was still crossing the Atlantic solely powered by the wind in her sails at a time when steamships were gaining ground in the passenger trade.

Dreadnought mainly carried European emigrants, and could carry 200 people in the “’tween decks”, or cargo hold, beneath the main deck. Booking passage in the tween decks was the cheapest option for people looking to immigrate to the United States, and the conditions could be dreadful. In contrast, if a wealthy person wanted to cross the Atlantic, they could pay to be a “cabin” passenger. As the name “cabin class” suggests these passengers were berthed in cabins, and enjoyed relatively luxurious accommodations. When sitting down at one of the four meals served each day in the dining saloon, a cabin class passenger might even be joined by the ship’s Captain— who was often treated as a celebrity.

This menu is certainly from a meal enjoyed in the cabin class dining saloon. The menu is a relatively simple piece of paper with the food items handwritten, but there is still a care for elegance and decoration demonstrated by the printed clipper ship and border.

The food list is divided by course with options for soup, entree, vegetable, salad, and pastry. The entrees may be the strangest to our modern sensibilities- including calves feet and pigeon pies- but the plum pudding with brandy sauce still sounds delicious. We can only wonder if this meal was served on a calm day at sea or if a few of the cabin passengers were battling seasickness and couldn’t enjoy their mock turtle soup.

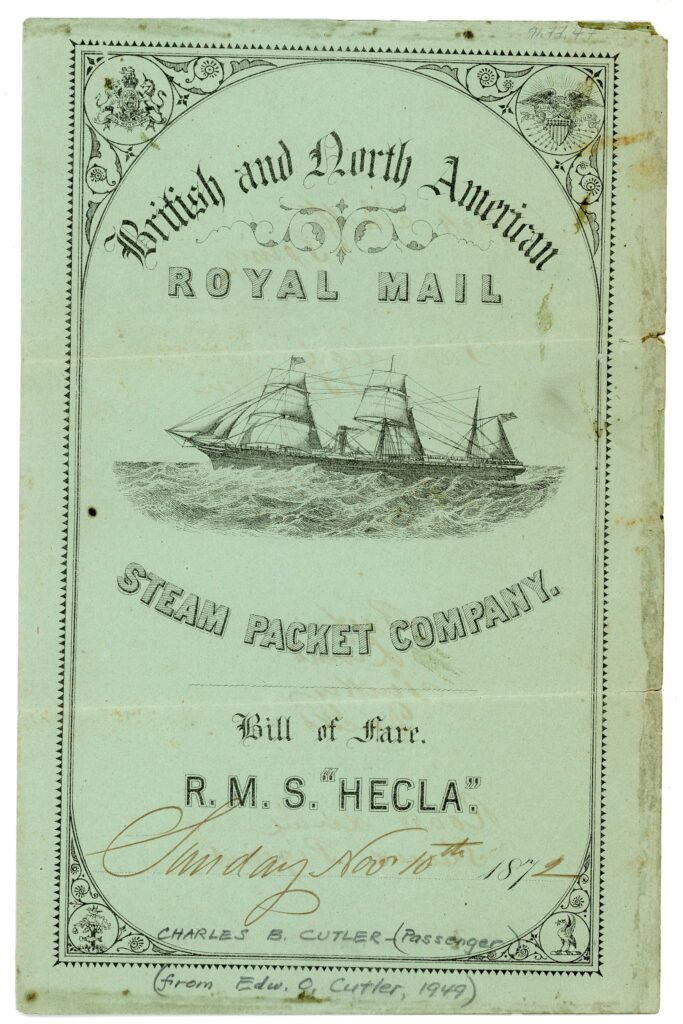

The cover of this menu gives a lot of information at first glance; this bill of fare was given to diners on board the ship RMS Hecla on Sunday, November 10th, 1872.

RMS Hecla was owned by British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company which you might know better by the name “Cunard”. Founded in 1840 by Samuel Cunard, the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company would later become one of the largest passenger shipping lines in the world.

The illustration in the center of the cover gives us an idea of how ships like Hecla differed from clippers like Dreadnought; the smokestack in the center gives away the fact that Hecla was a steamship—having a steam engine to power its propeller.

RMS Hecla Bill of Fare, November 10, 1872. Seamen’s Bank For Savings Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 1991.077.0047

Steamships from this period still retained their masts and sails. The hybridization of steam and sail technology was partially due to safety concerns around steam. What would be the fate of a steamship that ran out of coal (which was a real possibility before steam engines became more fuel efficient) in the middle of a voyage?

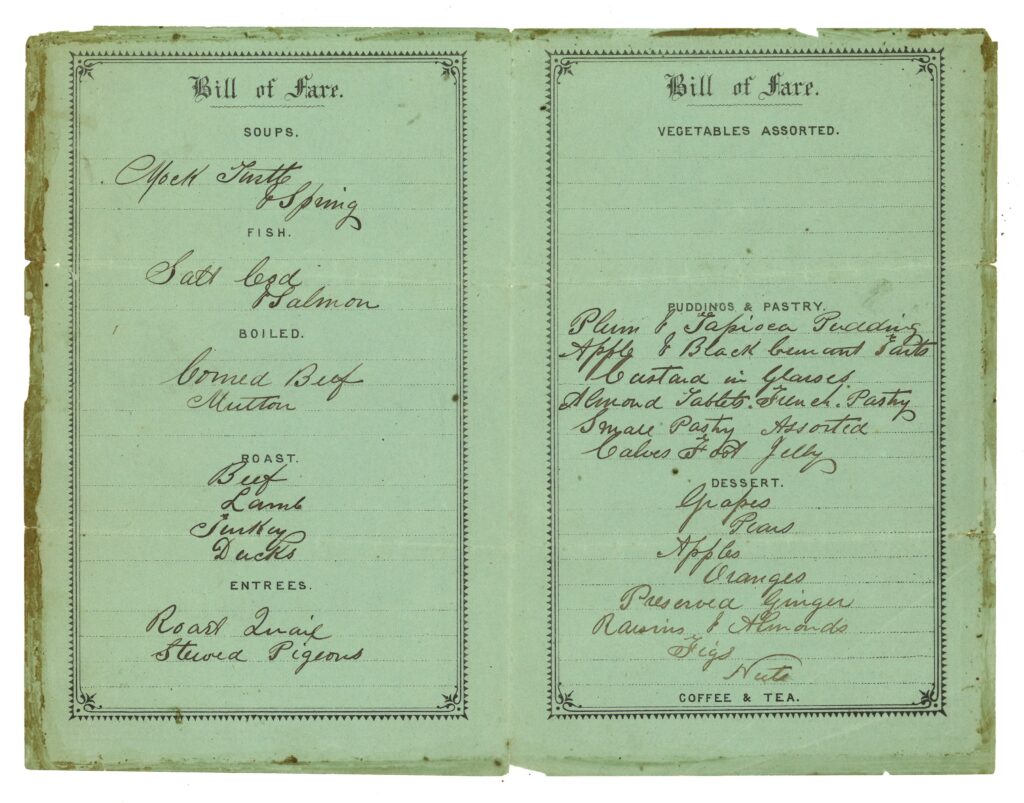

The actual list of food items can be found inside the fold of the menu. Like the Dreadnought menu, the items are handwritten- likely by a steward after consulting with the cook on what was going to be served that night. The meal is divided by course with sections for soup, fish, boiled and roast meats, entrees, vegetables, puddings and pastries, and dessert. Mock turtle soup shows up on this menu again, as do the calves’ feet though this time they are included under puddings as “calves foot jelly”.

Interestingly, the space beneath vegetables is blank. I found an announcement in the Boston Globe that said Hecla departed for Liverpool on October 30th, so maybe by the tenth day at sea the kitchen was running low on vegetables.

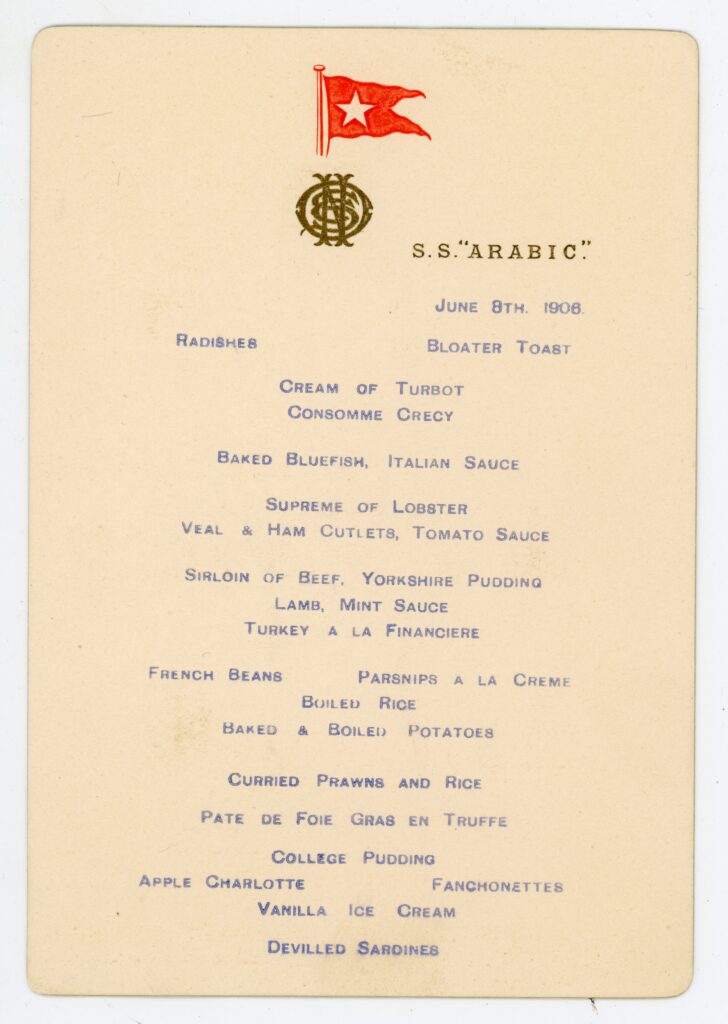

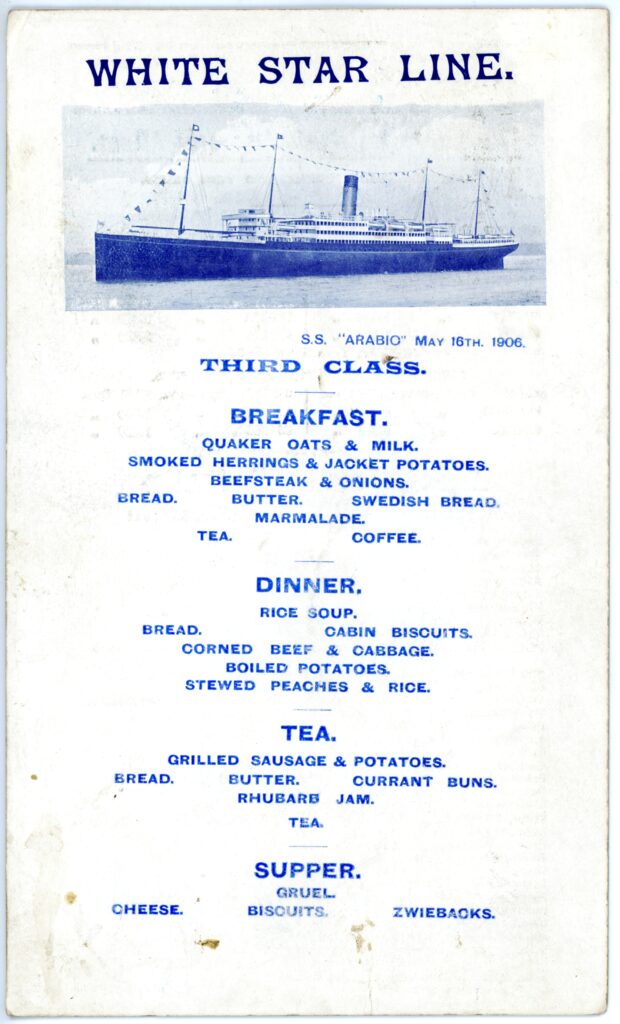

These two menus are both from 1906 voyages of the White Star Line ship SS Arabic. By the turn of the 20th century, ocean liners had largely done away with the auxiliary sails and their size had increased dramatically. If Dreadnought could carry less than 250 passengers, ships like Arabic could carry 1,400! In the years before World War I, transatlantic passenger travel would be characterized by ships like RMS Titanic and RMS Mauretania, known for their size and luxurious First-class accommodations.

But luxury is only part of the story. As the Museum explored in the exhibition Millions: Migrants and Millionaires Aboard the Great Liners, 1900-1914, the majority of passengers on these magnificent ships were traveling in Third Class, i.e. steerage. Immigration to the United States was at its peak, and from 1900 to 1914 nearly 13 million immigrants crossed the Atlantic by ship on their way to the United States.

Left: SS Arabic Menu, June 8, 1906. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.0902

Right: SS Arabic Menu, May 16, 1906. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.0899

The conditions in steerage had greatly improved from the mid-19th century, and in the case of RMS Arabic, Third-class passengers even got a menu. The Third-class menu is on the right and the First-class menu is on the left. Though they are from the same ship and the same year, there are some key differences.

The Third-class menu is for all three meals of the day (and tea), while the First-class menu is only for dinner since First-class passengers would have been given a new menu for each of their meals. The Third-class menu is printed in a single color, while the First-class menu has the added touch of the gold embossed elements. The food listed is also quite different: First-class passengers could indulge in some foie gras and lobster, while Third-class passengers are offered simpler, blander fare like gruel.

One thing these menus have in common is that they are entirely printed. Instead of having to handwrite menus for each passenger, the shipping lines began to equip their ocean liners with small printing offices. For the Millions exhibition, the letterpress printers at Bowne & Co. recreated these two 1906 menus using period printing presses and movable type. They pointed out how the lines of type for both original menus were slightly askew, and we wondered at the tricky task of printing hundreds of menus on a ship at sea.

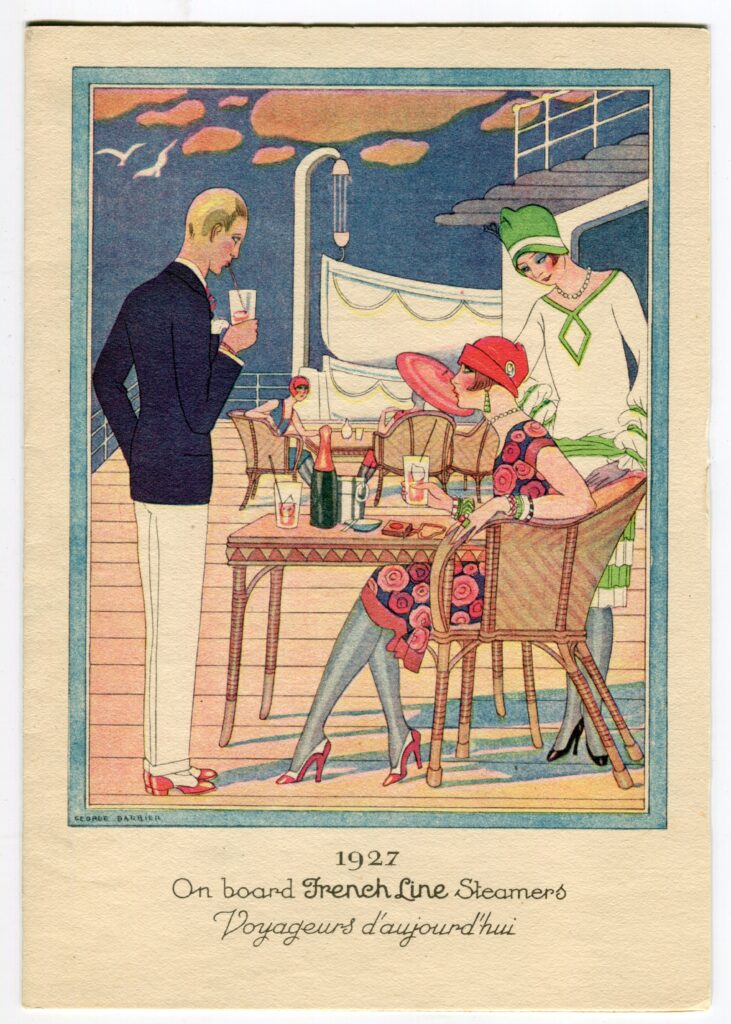

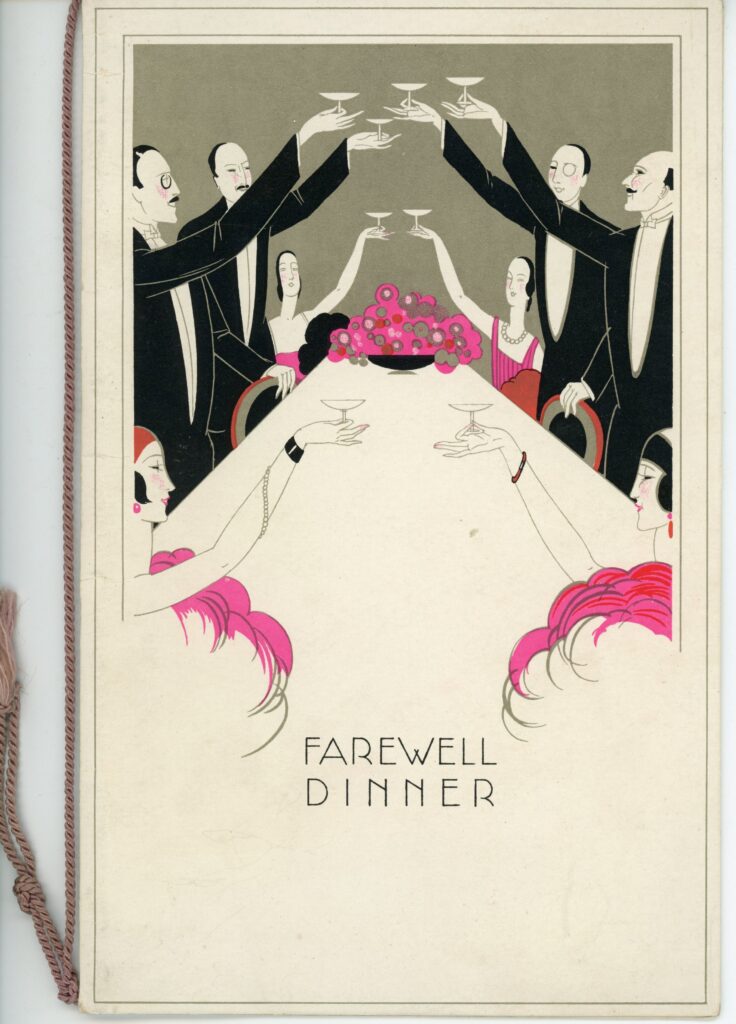

Though design and decoration can be seen in each menu we’ve looked at so far, menu covers became even more elaborate and colorful as the early 20th century went on. For these two Interwar Period menus, we even see an artist’s credit in the bottom left of the lithographs.

Left: SS Champlain Dinner Menu, October 2, 1932. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.1470

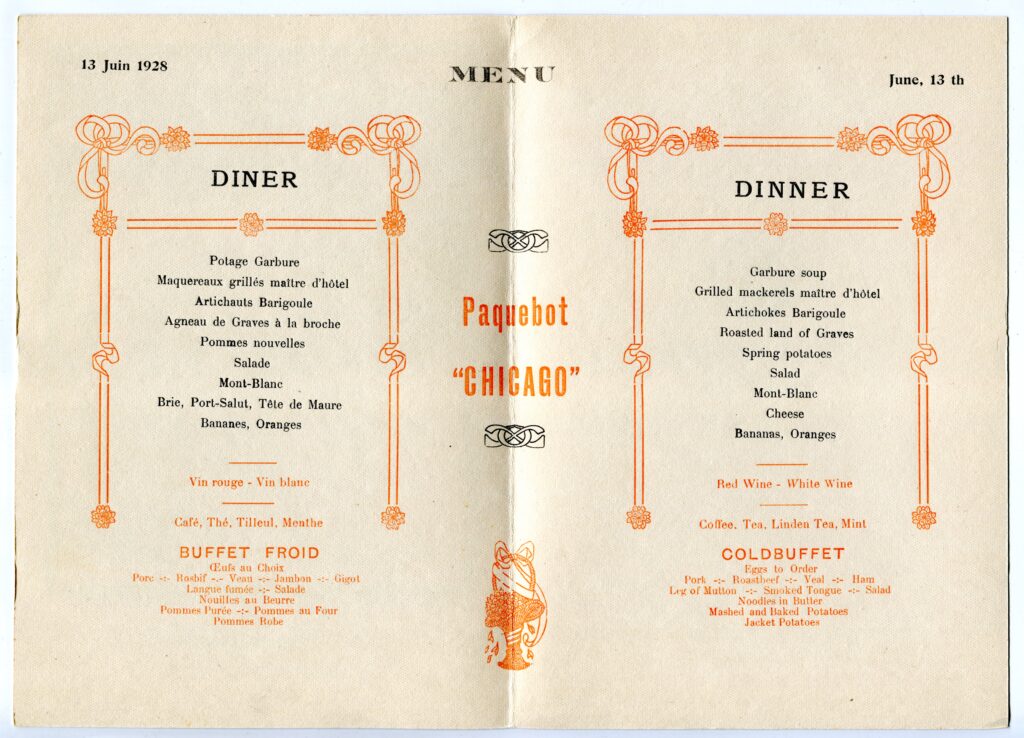

Right: SS Chicago Dinner Menu, June 13, 1928. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.1471

Both menu covers were designed by French illustrator George Barbier (1882–1932). Barbier was known for his fashion illustrations and even worked with renowned fellow Art Deco illustrator Erté (1892–1990)[1] George Babier Fan in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The two menu covers complement each other with one showing “Yesterday’s Passengers” of 1907 and the other showing the modern styles of “Today’s Passengers” of 1927.

SS Chicago Dinner Menu, June 13, 1928. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.1471

Looking at the interior of one of these menus, we get a peek at what was served aboard SS Chicago on June 13, 1928. The menu is actually printed twice, with the left side in French and the right side in English. Much of the ocean liner ephemera in the Museum’s collections include text in languages other than English. Though the English shipping lines like Cunard and White Star were important players in the transatlantic passenger trade, the French Line, the North German Lloyd Line, and the Hamburg American Line were competitors. Though the collections staff and interns sometimes have to work on translating these artifacts to catalog them, it’s nice when the work is done for us.

The menu includes items that can be ordered à la carte, like Garbure soup and grilled mackerel, but it also lists food that can be taken from a buffet of cold dishes like salad and noodles in butter. Don’t get spooked by the “Roasted land of Graves” on the English side— Graves is a type of wine, and the rest is just a nearly century-old typo of the intended “lamb”.

The passenger trade went through many changes during the early and mid-twentieth century. Immigration to the United States would never again reach the level seen before 1915, and without their millions of Third-class passengers shipping companies had to innovate. Overtime, many transatlantic liners replaced Third Class with a new “Tourist Class” advertised to people looking to travel on a budget. The explosion of recreational travel post-World War II also encouraged the growth of cruise ships. Passengers weren’t necessarily looking to go from Point A to Point B, but instead wanted to have a “round-trip” —stopping at interesting locations along the way.

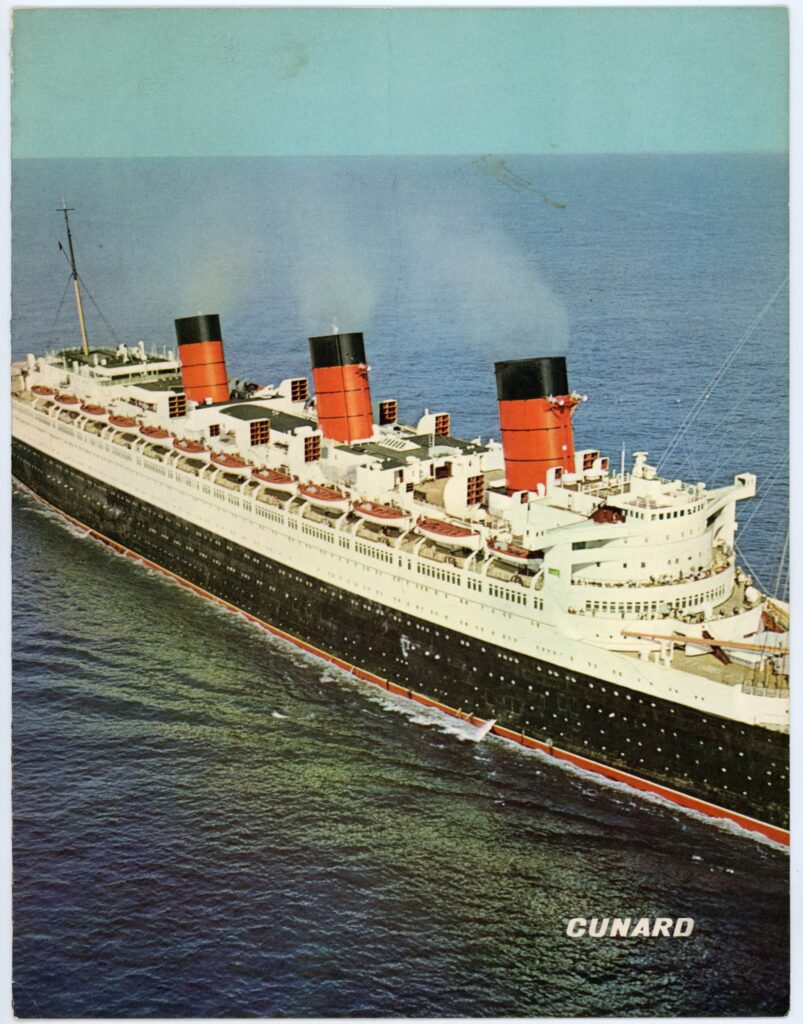

The rise of commercial air travel in the 1950s and 60s was a massive revolution for transatlantic ocean liners. Ocean travel had to compete with the convenience and speed of “air liners” by selling the experience. The shift can be seen in Cunard’s slogan, ”Getting There is Half the Fun!”, adopted in the 1950s.

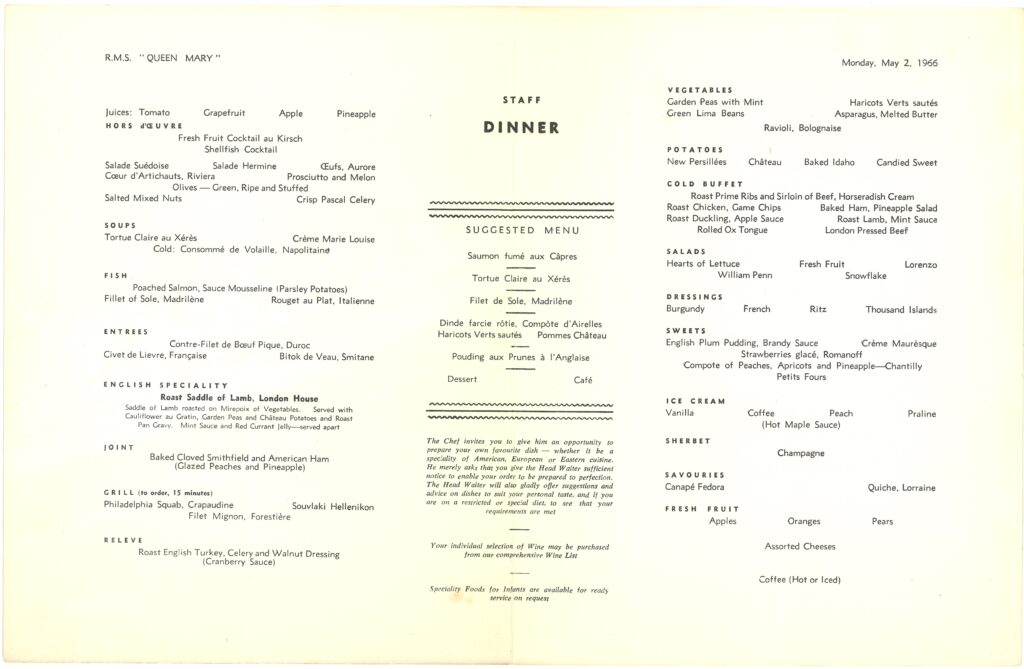

RMS Queen Mary Dinner Menu, May 2, 1966. The Robert L. Mink Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 2003.039.0212

This menu from Cunard’s RMS Queen Mary was placed before passengers on May 2, 1966. Including the beverages there are over 70 options listed! And that’s not all: in small print there is a humble invitation from the Chef for passengers to ask for any dish, “whether it be a specialty of America, European, or Eastern cuisine”, so long as they give the Head Waiter sufficient notice. If the passenger didn’t feel like reading the whole menu and making so many decisions, there is also a suggested menu in the center.

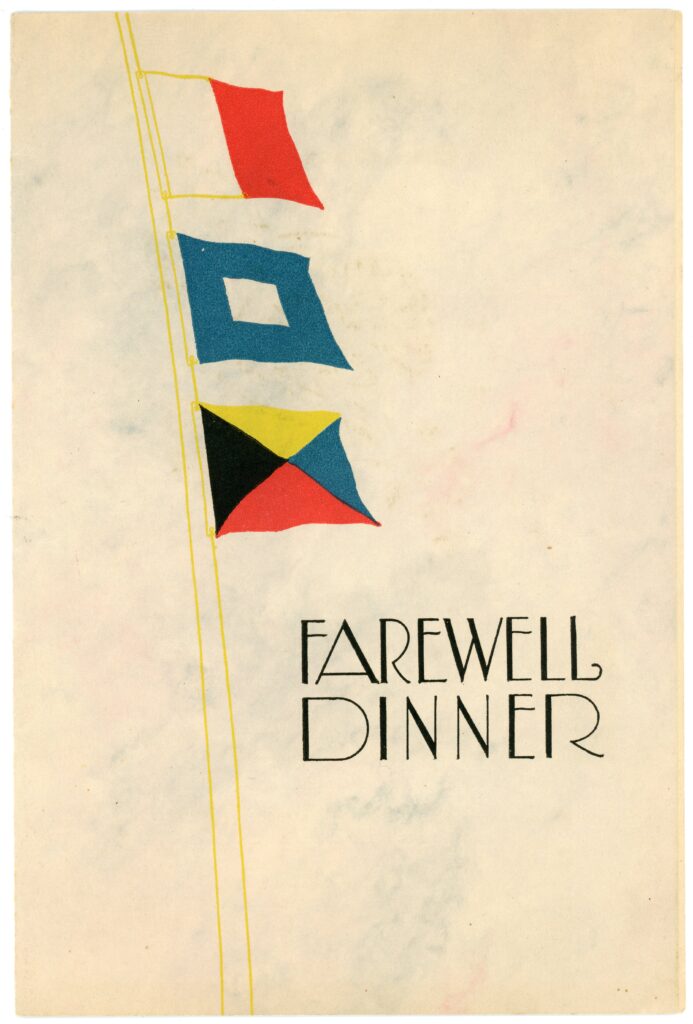

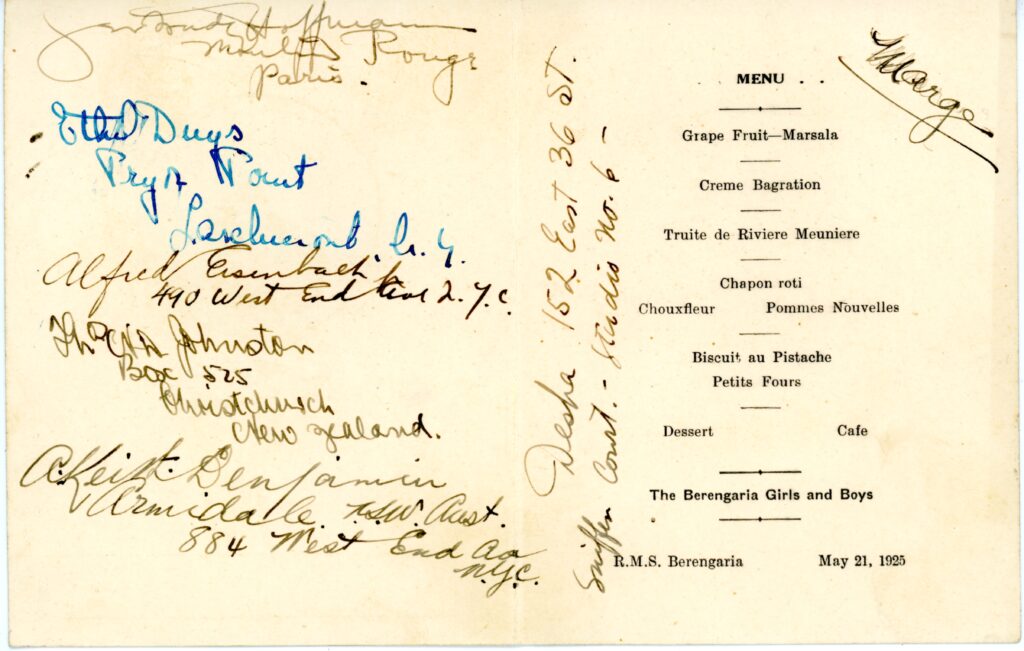

To close this peek into the menus in the Museum collection, I chose three “Farewell Dinner” menu covers. The last night of a voyage was often a special affair, as passengers had one last meal with their tablemates. Some menus include a collection of autographs and mailing addresses so that the new friends could stay in touch with one another.

Left: SS Pennland Farewell Dinner Menu, September 3, 1926. Ocean Liner Museum Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 2003.023.0889

Center: SS Leviathan Menu, November 28, 1928. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.0186

Right: SS Homeric Menu, Mach 22, 1964. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.4542

RMS Berengaria Menu, May 21, 1925. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.0892

The Museum holds hundreds of menus from over a century of ocean crossings. Each one saved for a reason—picked up from the table by a passenger and held on to long after their voyage was over. A menu is only meant to be used once and then thrown away, but for some people their menus become a souvenir. As a collections staff member, I enjoy working with the ocean liner collections for their historical value, but I also appreciate caring for objects that, at one time, connected people to their memories, adventures, and journeys.

Additional readings and resources

The New York Public Library’s “What’s on the menu?” project.

“Savoring a Bygone Splendor: The Maritime Menu” by Kate Murphy, published on The New York Times on September 9, 2013.

References