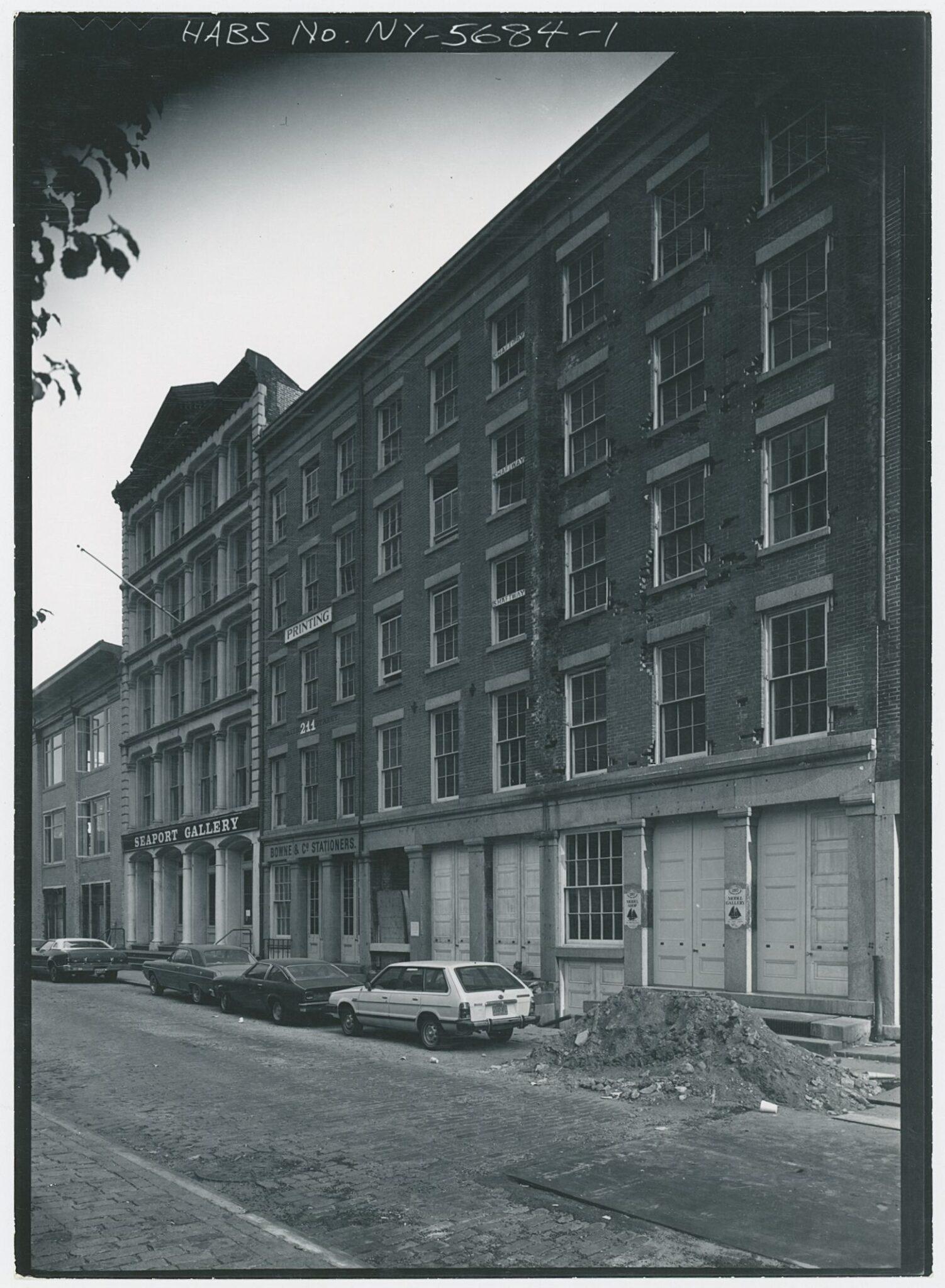

207–211 Water Street

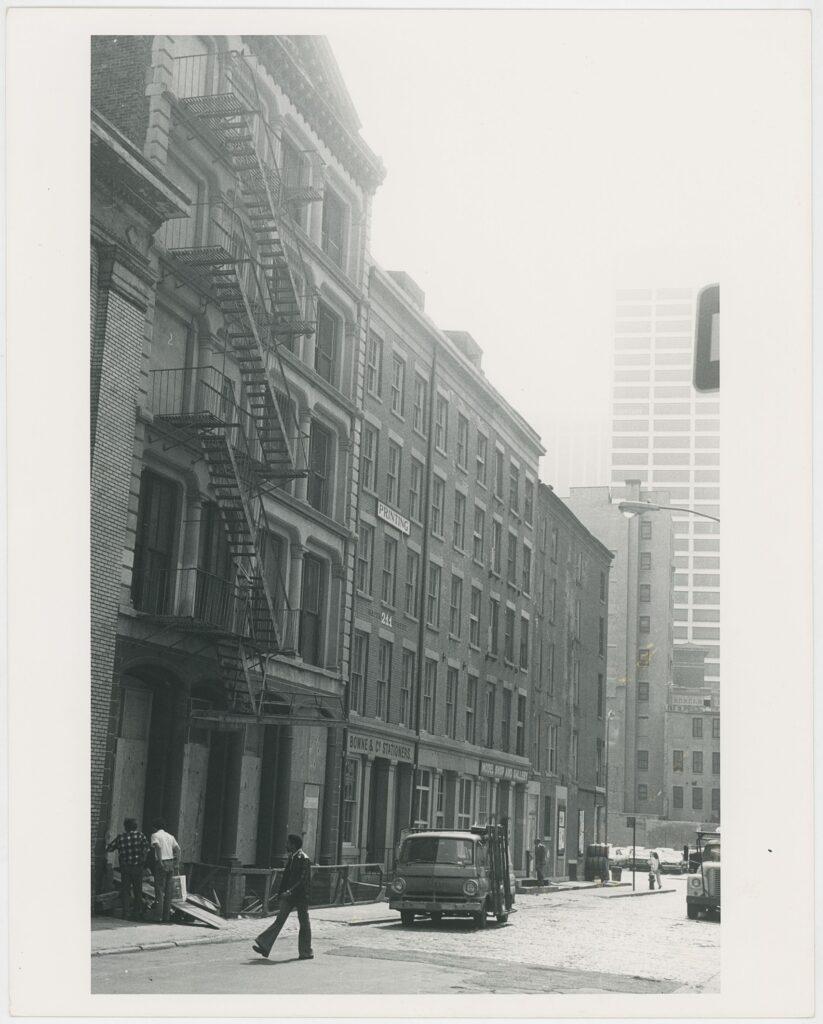

These three brick buildings at 207, 209, and 211 Water Street are among the best-preserved examples of the Greek Revival style architecture in New York City, which flourished during the 1830s and 1840s. The ground floor shops are characterized by monolithic granite frames, in contrast with the stories above, which are faced with warm-toned bricks.

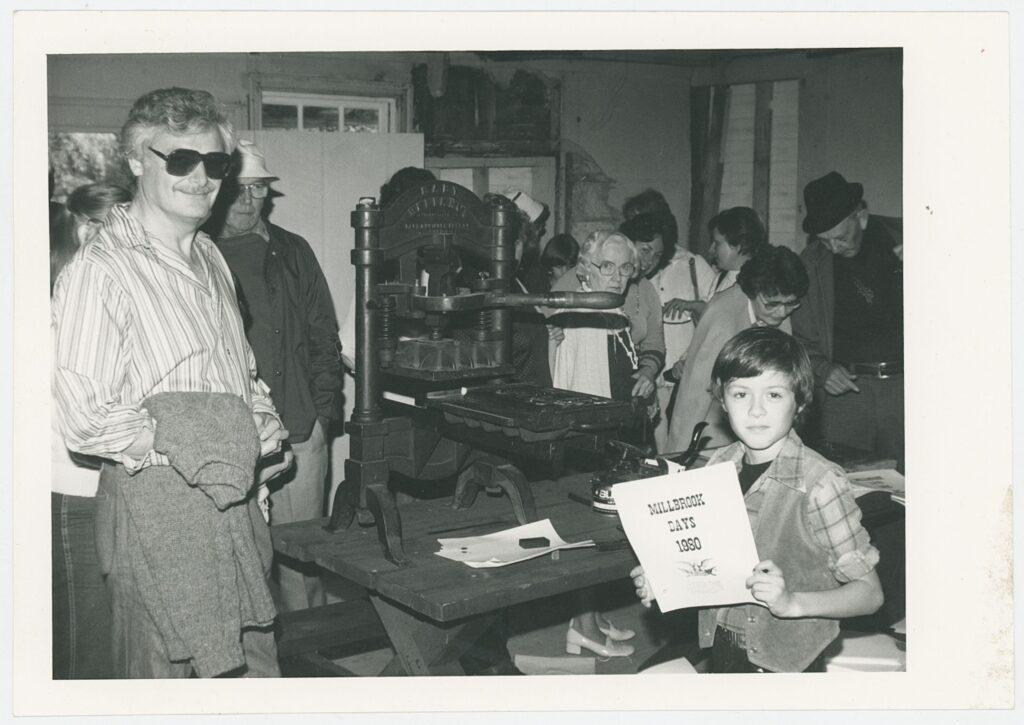

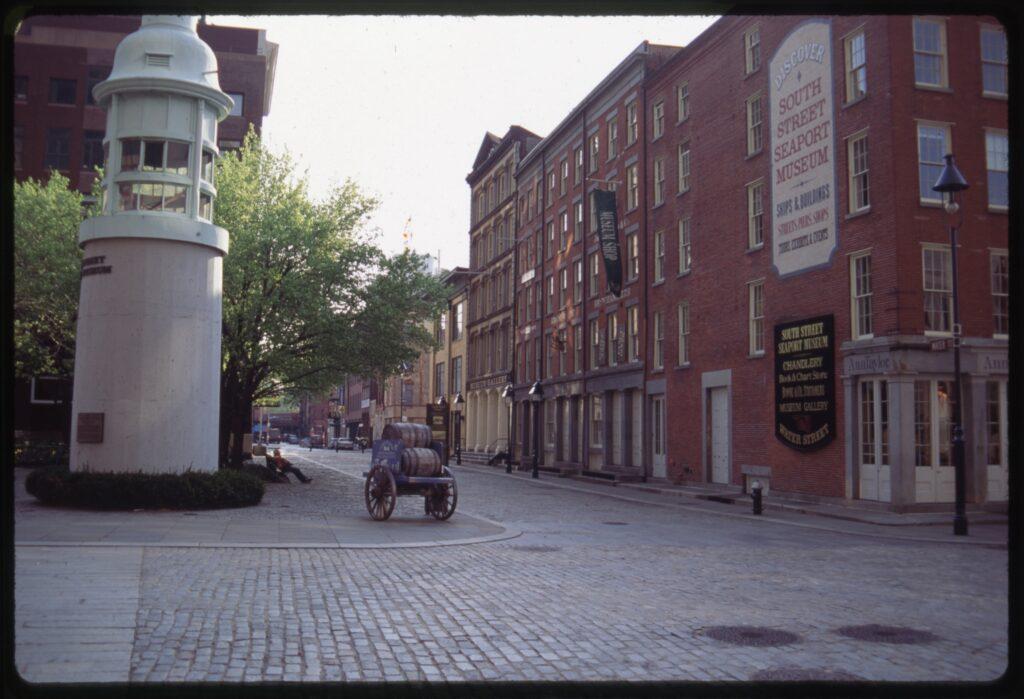

Today, these historical buildings are part of the South Street Seaport Museum, and are used to underscore the rich history of printing and its deep connection to the history of the Seaport. Bowne & Co., Stationers at 211 Water Street is a 19th century-style gift emporium with a carefully-curated selection of unique wares including books, candles, home decor, stationery, oddities, as well as house-designed and printed paper goods.

Bowne Printing Office at 209 Water Street is a working letterpress office where Seaport Museum visitors can attend monthly open houses and workshops as well as seasonal printing programs, and work with professional printers to order and design custom letterpress works. All text is set and composed by hand using Bowne’s historic type collection and then printed on original 19th and mid-20th century printing presses. 207 Water Street is now used primarily as a Museum Program Space where visitors can participate in programs and events as well as family activities on many weekends throughout the year.

Greek Revival

These Water Street warehouses were constructed for P. J. Hart, Gabriel Havens, and David Lounderback between 1835 and 1836 in the Greek Revival style, replacing three earlier structures. 18th-century maps of the area indicate that the land on which 209 Water Street stands was filled no earlier than 1755, with the land-making process ending sometime between 1767 and 1789.

Beginning in 1829, nearly every new building in the Seaport was built with Greek Revival elements. Hundreds of older brick buildings had their arched doors and windows replaced with granite storefronts like the one visible today at 207-211 Water Street. Both the material—granite—and the design—post and lintel—were imported from New England. Steam quarrying methods, railways, and specially-rigged sloops made granite practical for use outside New England. The style of this Water Street row originated in Boston in 1810 and came to New York via American architect and civil engineer Ithiel Town’s (1784–1844) design for the Pearl Street silk store of merchants Lewis Tappan (1788–1873) and Arthur Tappan (1786–1865)[1]“Lewis and Arthur Tappan were brothers who earned a fortune importing silk from Asia. In 1841, Lewis went on to form the Mercantile Agency, which is today known as Dun and Bradstreet, a … Continue reading.

The new warehouses were leased in 1836 to importers and stove merchants[2]Inventory of Structures in the Brooklyn Bridge S.E. Urban Renewal Area, 1968, pp. 8-9.. Louderback, a mason by profession, probably constructed his own building and may have also built the additional two structures.

At the time, many masons built Greek Revival stores by studying examples on the street and in the builders’ handbooks[3]South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report, Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1977, p. 5..

Additionally, the use of Flemish-bond brick techniques in the upper stories—already ten years out of date in New York—suggest that the builder was not an architect. Finally, in 1830, Lauderback purchased two designs for stores from architect William Vine (active 1830s–1840s) indicating that it was not an unusual practice for a builder to do such a thing[4]“South Street Seaport Museum, 207-211 Water Street, New York County, NY” Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress). HABS NY-5683 https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0906/.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator. South Street Seaport Museum, 207-211 Water Street, New York County, NY. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/ny0906/

The Tenants

Like most of the buildings in the Seaport, 207, 209, and 211 Water Street have contained a variety of businesses across the centuries including a tobacco factory, meat market, trucking firm, and several stove dealers[5]“At 209 Water Street, stoves and boilers were sold by a man named Almond Dunbar Fisk (1818–1850). Fisk used his knowledge of air-tight structures for his stoves to develop iron coffins and on … Continue reading. Stove dealers remained at the Water Street addresses throughout the 19th century, while in the 20th century, most of the tenants were involved in trucking or storage.

The earliest recorded alteration to the warehouses took place in 1909, when William Ottmann and Co.[6]The Ottmann Family came to America in 1849, starting with Philipp Ottmann (1832–1876) and his sister-in-law Margaretha Becker Ottmann and her eight children between 1859–1864. Philipp Ottmann … Continue reading hired architect Julius Kastner (active 1880s–1910s) to alter 207 and 209 Water Street into a meat packing and exporting establishment, installing coolers and pickling rooms. By 1913, William Ottmann and Co. took over 211 Water Street as well, and had architect William S. Miller connect all three buildings by cutting openings in the party walls on all floors.

In 1919, the fish market business W. A. Winant and Co. had architects Renwick, Aspinwall and Tucker (1904–1920) connect 203 Front Street and 207 Water Street through the rear. In 1920, when 209 Water Street became a fish market, architect I. B. McNeill bricked up the openings connecting 209 to the other two buildings, rearranged doors, and removed all concrete floors and all insulation. The rear windows on all floors were reopened. Still a fish market in 1921, 209 Water Street was connected to 204 Front Street by breaking through the rear wall. The alteration was designed by Claude H. Valentine.

The Restorations

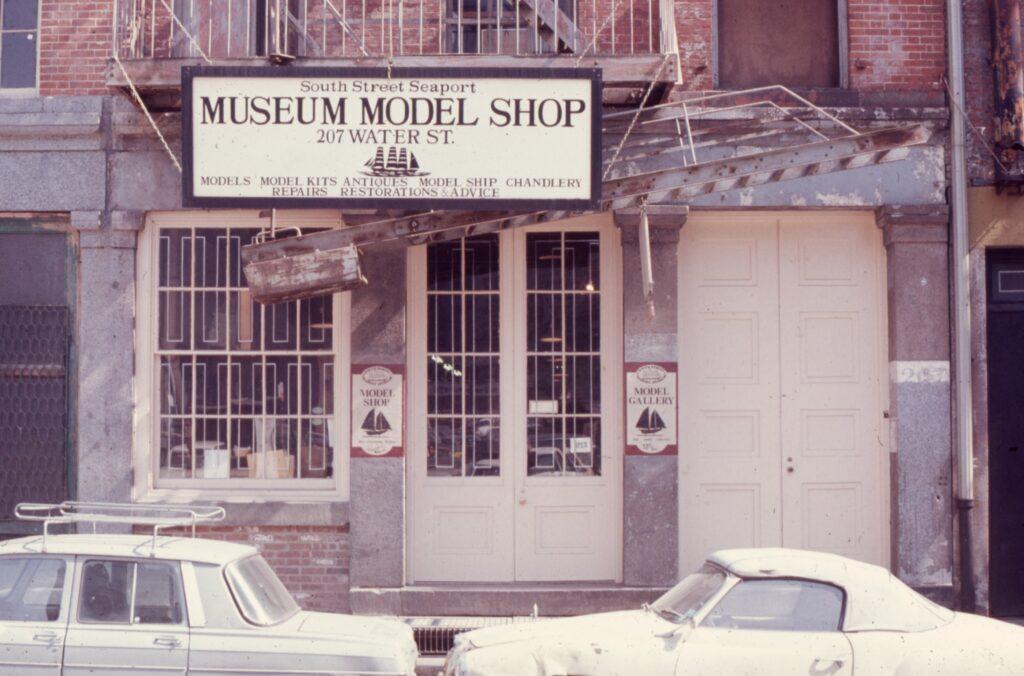

The buildings were vacant in the mid-20th century, and restored by the South Street Seaport Museum. 211 Water Street was one of the first preservation projects undertaken by the Museum, in 1973 and 1974, moving Bowne & Co. Stationers into the warehouse, to create the gift emporium and an operating printing office based on the 19th-century prototype.

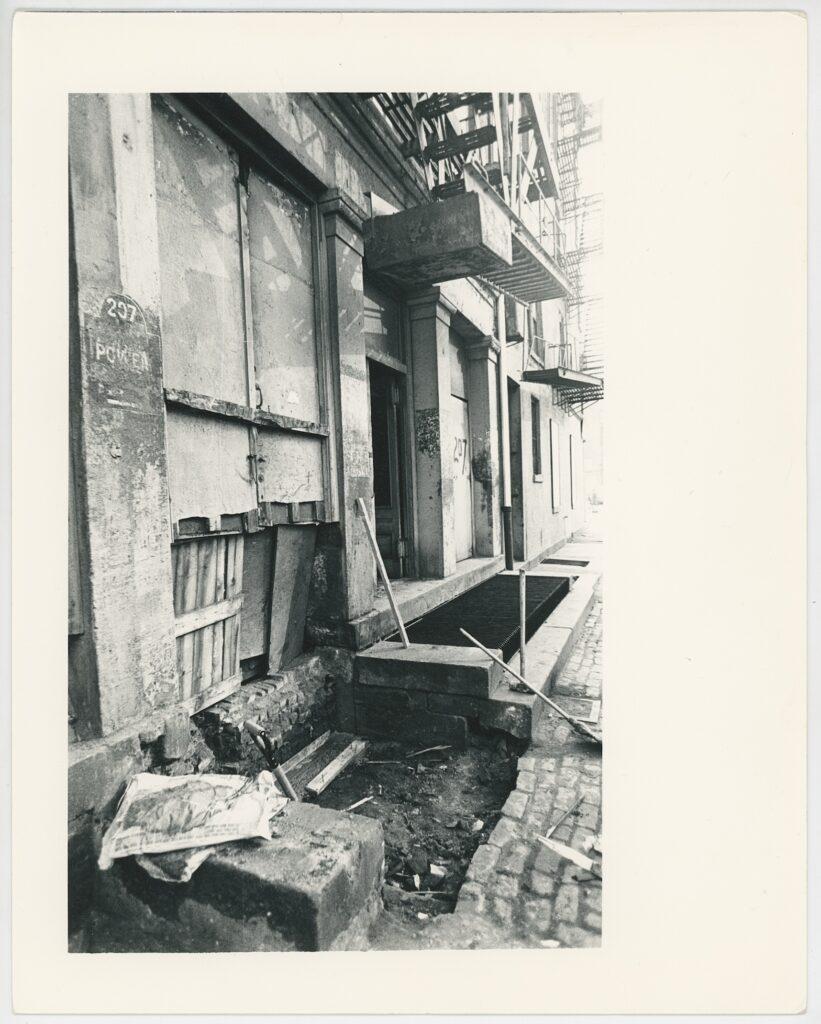

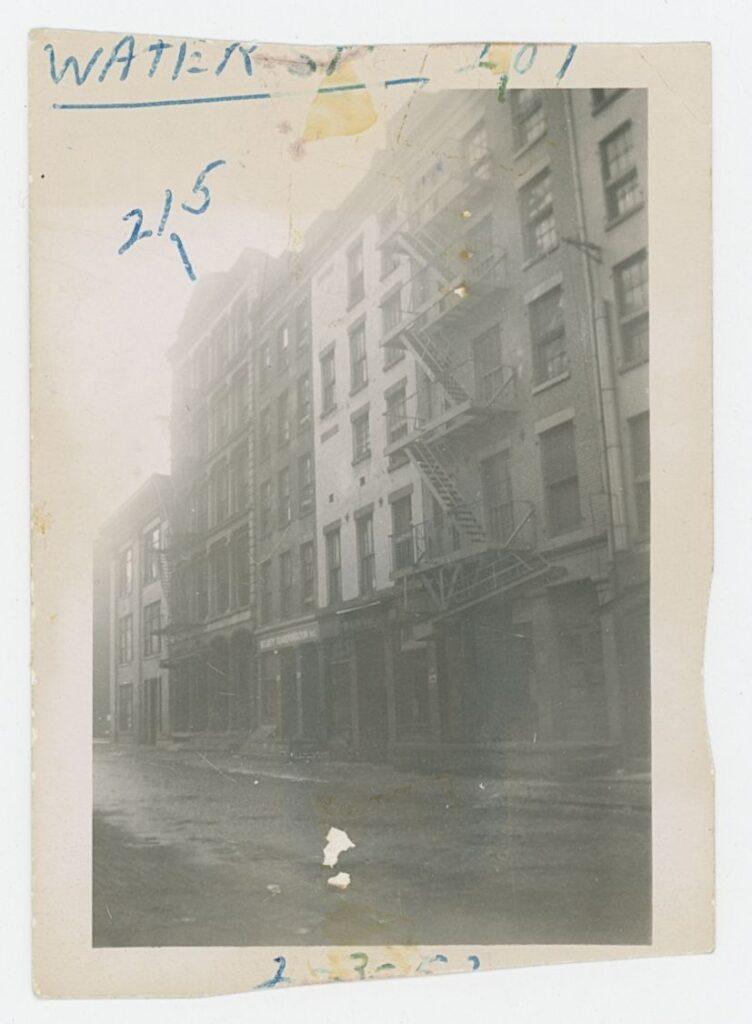

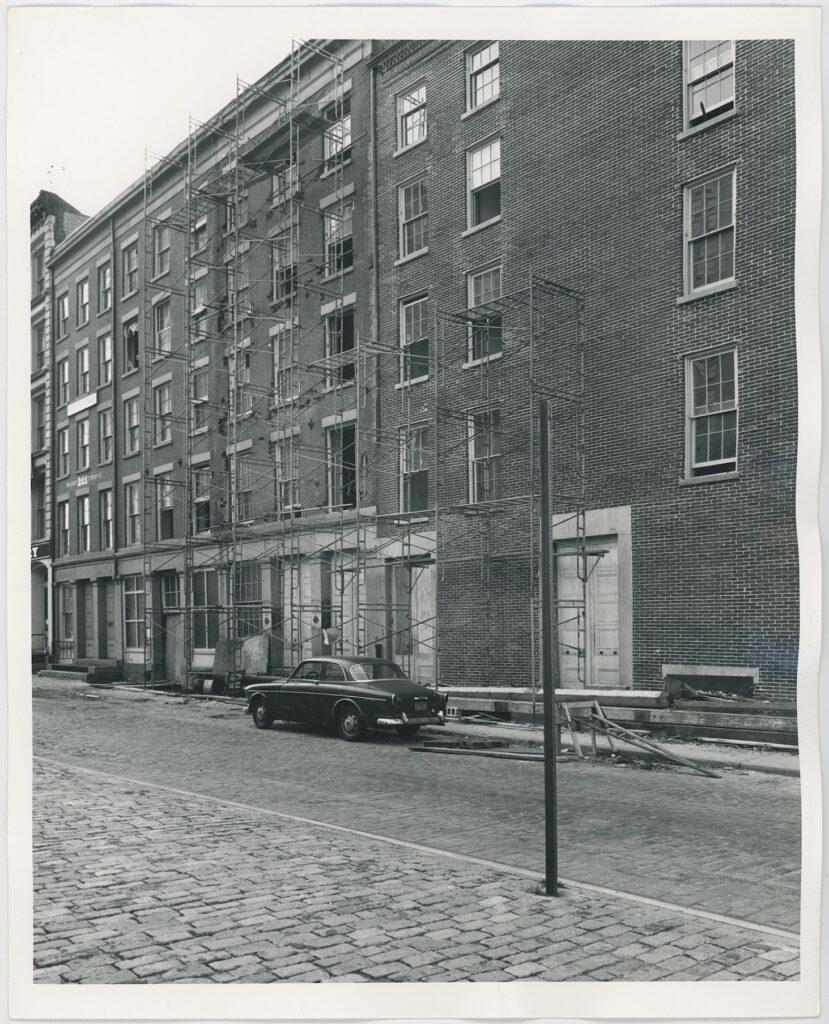

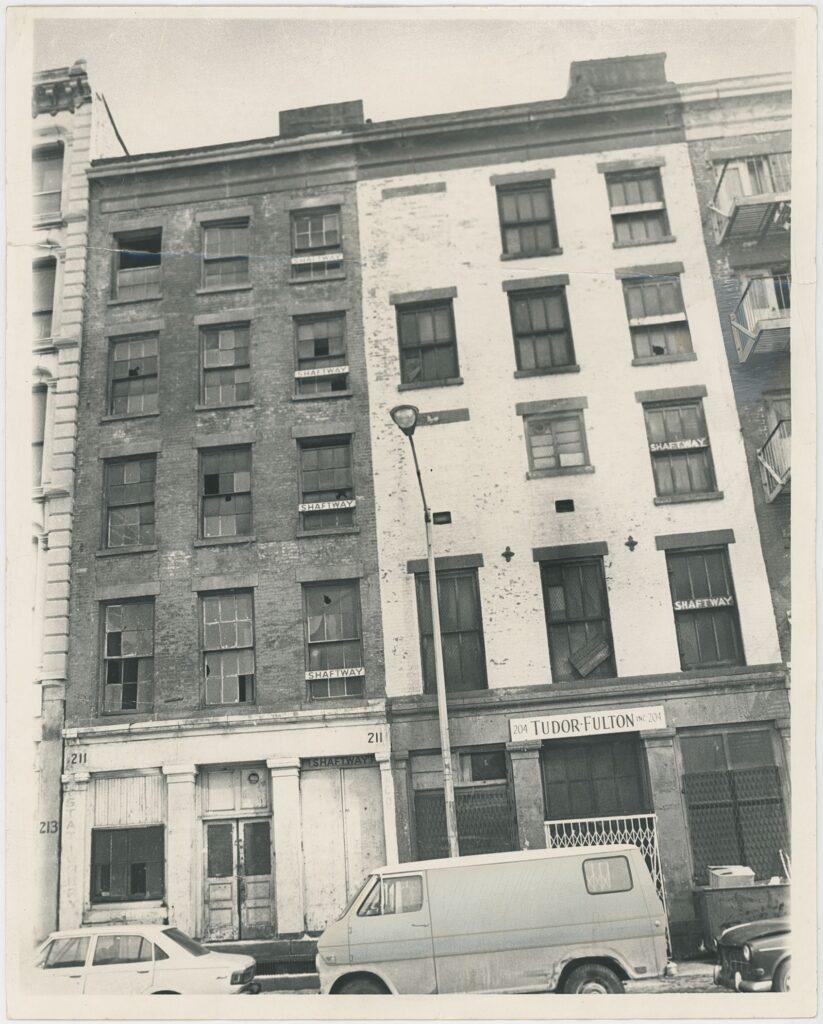

Left: 207-209 Water Street, ca. 1972-1973. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive

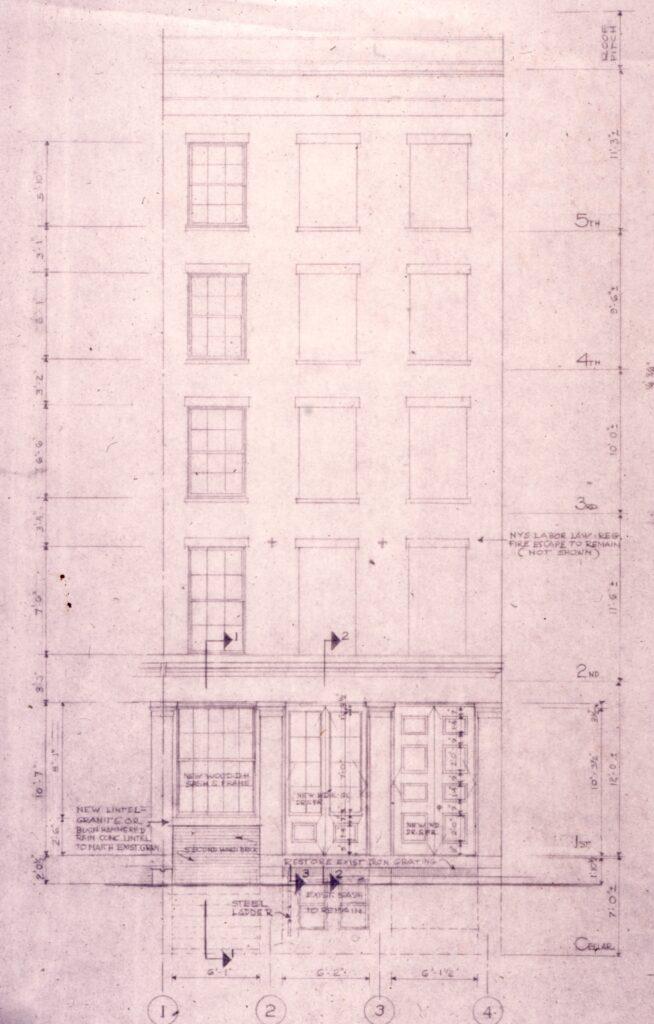

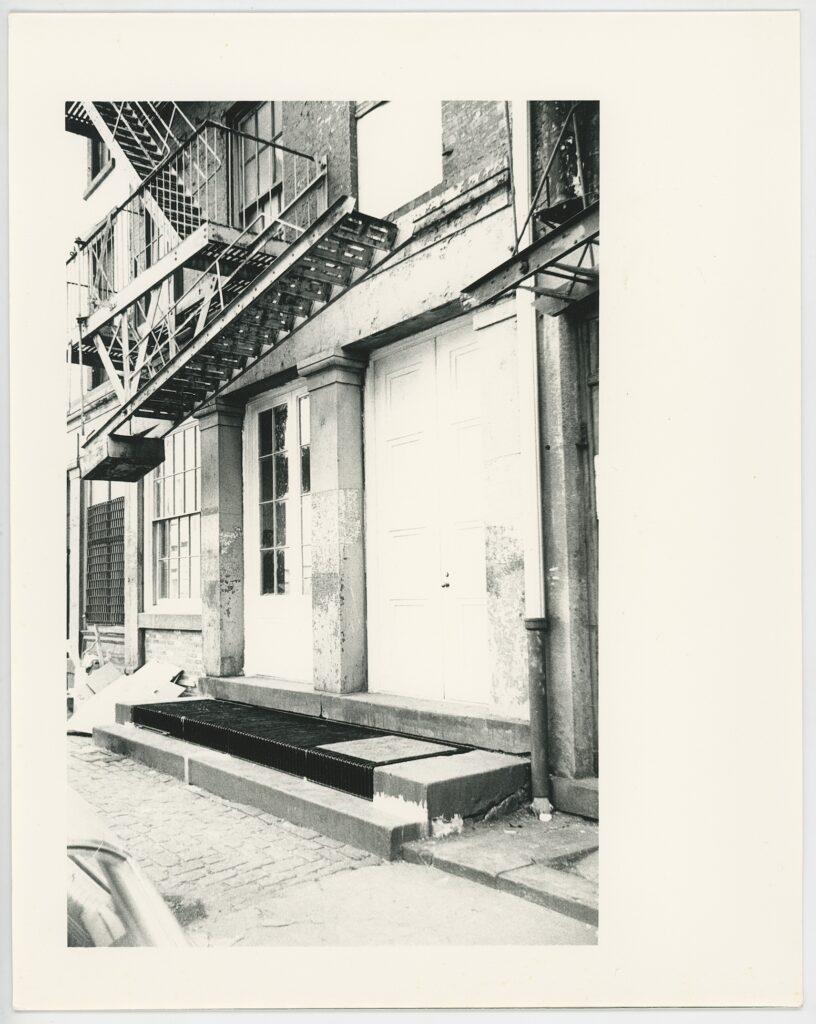

Right: 207 Water Street, 1973. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive

The three structures, along with the buildings along the block formed by Water, Beekman, Front, and Fulton Streets—called Block 96W—were photographed in 1977. The interior survey gives an incredible snapshot of their condition at the time and captured many Museum’s artifacts in storage and on display—supplementing our records of the collections.

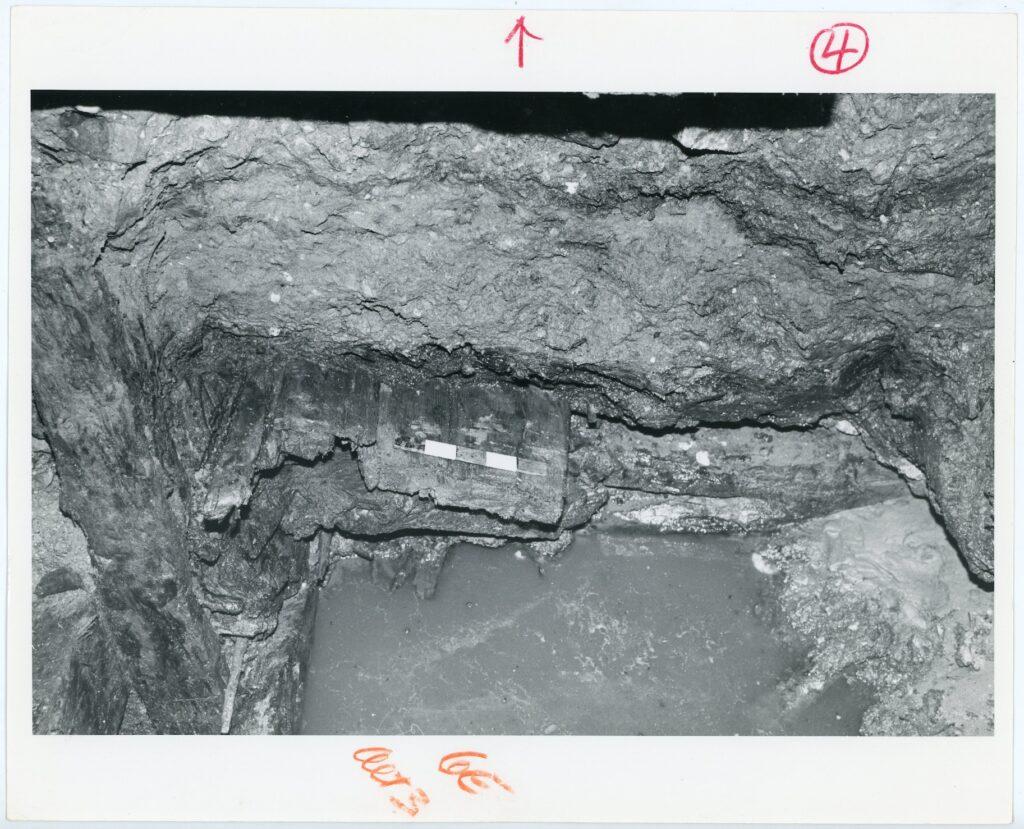

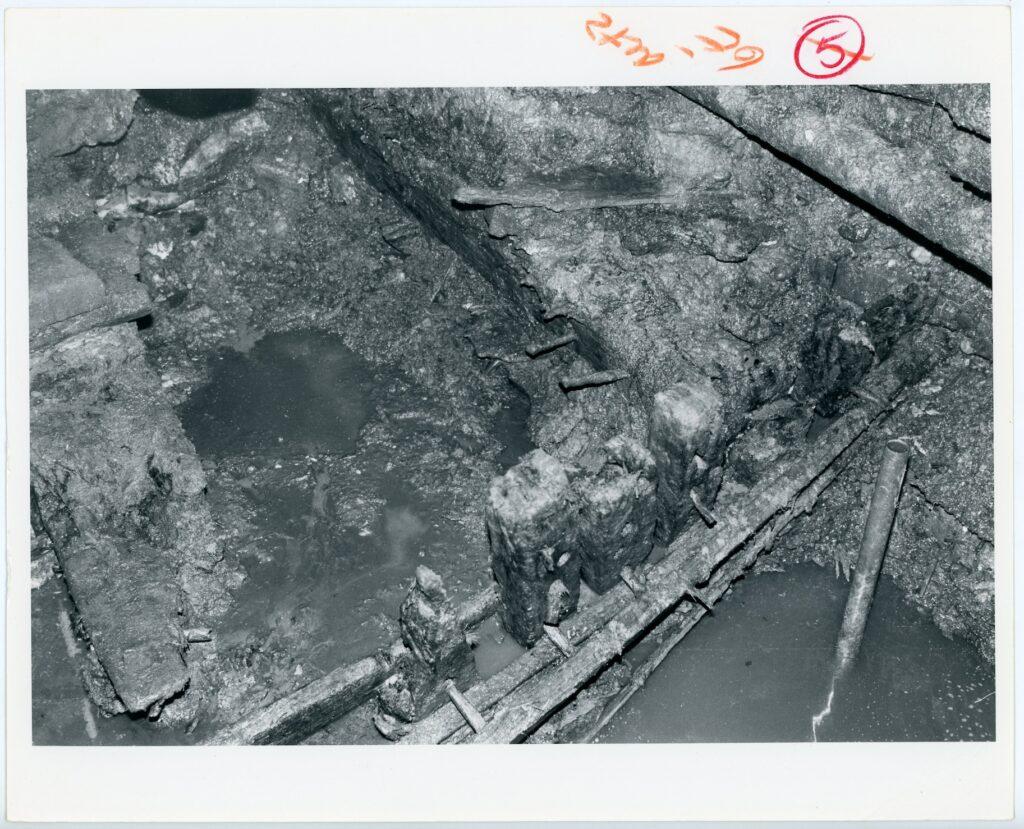

In 1978, the Museum wanted to install a sump pump in the basement of 209 Water Street due to ongoing flooding issues in the building’s basement. When it became apparent that the amount of digging for this project would be more than anticipated and that cultural material might be disturbed, archaeologists from City College were called in to monitor the digging. What they discovered sheds light on the original land-making practices in the area.

Archaeologists expected they would be excavating and studying 18th century infill, and indeed, the artifacts they found were representative of daily life in New York in the 18th century, included gin and wine bottles, clay pipes, shoe leather, many types of ceramics of mostly British manufacture, and even two coins—a George III farthing dating between 1771–1774, and a George II shilling possibly dating between 1727–1760[7]The Water Street Site: Final Report on 209 Water Street by Roselle Henn, 1978, pp. 158-162.. But it was one large artifact that most captivated archaeologists and staff at the Seaport Museum.

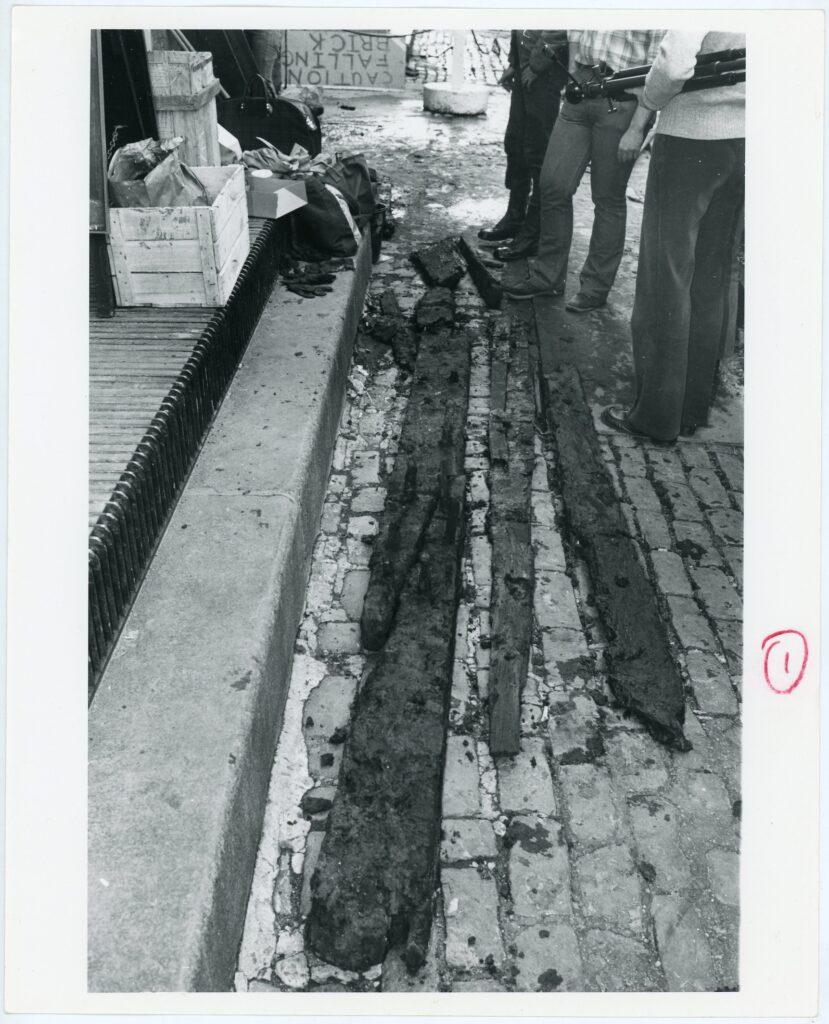

As digging progressed, a group of wooden planks were discovered, which were initially thought to be part of the cribbing used to hold infill in place. However, it soon became apparent that the planks were the frame of a ship that had been part of the materials used as infill. The ship was examined by the Museum’s historian at the time, Norman Brouwer, along with a naval architect and a maritime archaeologist.

Top: Excavation of a ship at 209 Water Street, 1978. Photo by Norman Brouwer. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive

Bottom: Planks recovered from the ship under 209 Water Street, 1978. Photo by Norman Brouwer. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive

The remains of the ship were in an excellent state, preserved by the water-logged soil they had been contained within, and several features of the ship could still be identified. The ship’s treenail (wooden “nail” or dowel) construction method was still identifiable, and several knees (braces) were still articulated with the ship’s frames and beams. The exterior of the hull was identified by a coating of tar and horsehair, which was commonly applied to the outer planking of 18th century wooden ships to protect them from worms, particularly for the ones sailing in the tropics.

Based on the size of the remaining timbers, the ship is estimated to have been between 80 and 100 feet in length, with a displacement of about 200 tons. After consulting with the President’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, the National Park Service’s National Register Unit, and the New York State Department of Historic Preservation, the Museum decided that the ship under 209 Water Street should be reburied and preserved in situ until such time when the Museum had the resources to conduct a formal, full-scale excavation[8]The Ship in Our Cellar by Norman Brouwer, Seaport Magazine, Fall 1980, p. 23..

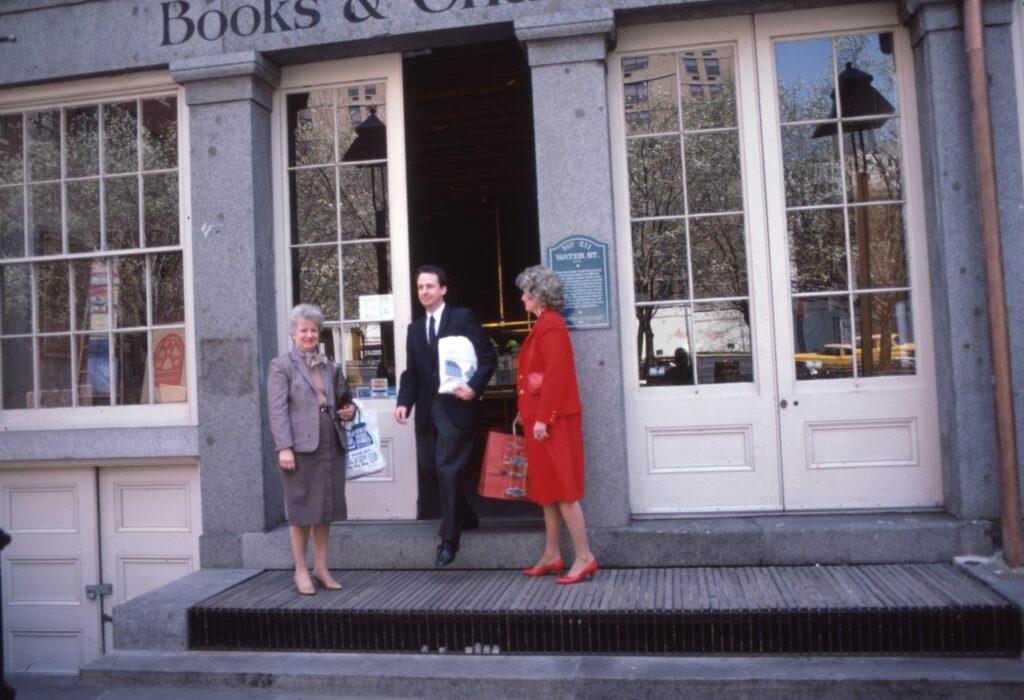

“Water Street” ca. 1982. 35mm slide. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive

The building at 211 Water Street has housed the Museum’s Bowne & Co. Stationers since its opening in 1975. Established in 1775, the firm Bowne & Co. is one of the oldest and largest job printers in New York’s first neighborhood. In honor of the company’s bicentennial, Bowne & Co., Inc. partnered with the South Street Seaport Museum to restore the historic storefront at 211 Water Street and create this offshoot of Bowne & Co. Stationers as both a functioning business and a museum installation, preserving and celebrating the firm’s legacy.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch

More Views of the Hart-Havens-Lauderback Buildings from the Archives

South Street Seaport Museum

By subway: Take the A, C, 2, 3, J, Z, 4, or 5 train to Fulton Street.

By bus: Take the M-15 SBS or M-15 to Fulton Street.

By water: The NYC Ferry, and New York Waterway provide service to Pier 11. The Staten Island Ferry provides services to Whitehall Terminal.

Parking: Parking lots can be found at Front and John Streets, as well as 294 Pearl Street.

References

| ↑1 | “Lewis and Arthur Tappan were brothers who earned a fortune importing silk from Asia. In 1841, Lewis went on to form the Mercantile Agency, which is today known as Dun and Bradstreet, a billion-dollar corporation. In the early-mid 19th century, more and more white New Yorkers were in favor of ending slavery, but very few were for equal rights. The Tappans were different. They demanded “universal liberty.” Whites, such as the Tappans, who spoke out for equality were hated and often targeted. During the riots of 1834, pro-slavery mobs attacked the Tappans repeatedly.” MAAP Mapping the African American Past, Columbia University https://maap.columbia.edu/place/5.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Inventory of Structures in the Brooklyn Bridge S.E. Urban Renewal Area, 1968, pp. 8-9. |

| ↑3 | South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report, Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1977, p. 5. |

| ↑4 | “South Street Seaport Museum, 207-211 Water Street, New York County, NY” Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress). HABS NY-5683 https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0906/ |

| ↑5 | “At 209 Water Street, stoves and boilers were sold by a man named Almond Dunbar Fisk (1818–1850). Fisk used his knowledge of air-tight structures for his stoves to develop iron coffins and on November 14, 1848, he received the patent for his “Air-Tight Coffin of Cast or Raised Metal.” These new air-tight and waterproof coffins safely transported deceased bodies across the country without the fear of decomposition or spreading disease. […] The sudden success of the business prompted Fisk to open a showroom at 401 Broadway in New York City while utilizing Fisk’s stove and boiler shop at 209 Water Street as the coffin shipping depot. Unfortunately, Fisk’s good fortune quickly ran out. In September 1849, a fire destroyed his iron foundry in Queens along with the majority of his coffins. He had to use his coffin patent as collateral for refinancing his business. On October 13, 1850, Fisk passed away from an unknown cause and never saw his business find success again.” Learn more about it on the Collections Chronicles Blog “Spooktacular Discoveries. Haunting Highlights from the Seaport Museum’s Collections” |

| ↑6 | The Ottmann Family came to America in 1849, starting with Philipp Ottmann (1832–1876) and his sister-in-law Margaretha Becker Ottmann and her eight children between 1859–1864. Philipp Ottmann & Co., William Ottmann & Co.,, and Ottman & Company, were meat purveying firms founded in the Fulton and West Washington Markets starting in 1859. Philipp Ottmann & Company operated at the Fulton Market between 1860–1876. Wm. Ottmann & Co. operated at the Fulton Market between 1876–1925. Ottman & Company operated at the West Washington Market between 1918–1986. https://www.wehatetowaste.com/ottman-nyc/ |

| ↑7 | The Water Street Site: Final Report on 209 Water Street by Roselle Henn, 1978, pp. 158-162. |

| ↑8 | The Ship in Our Cellar by Norman Brouwer, Seaport Magazine, Fall 1980, p. 23. |