Wavertree was built at Southampton, England in 1885. Southgate,[1]The intended name for the ship that would become Southgate, and later Wavertree, was Toxteth. This name was used in correspondence between Leyland and Oswald, Mordaunt and Co. as the ship was built; … Continue reading as she was known at the time, was built by the Oswald, Mordaunt and Company in the shipyard of Woolston, Southampton. Two years after her launch she changed ownership to R. W. Leyland & Company of Liverpool and was renamed Wavertree.

She was first employed to carry jute, used in making rope and burlap bags, between eastern India (now Bangladesh) and Scotland. When less than two years old, she entered the tramp trades,[2]”A ship that regularly sails on a fixed route following a schedule is known as a liner. This is because they have regular ports of call. On the other hand, we have ships that do not follow a … Continue reading taking whatever cargo would pay to whatever place in the world.

In 1910, after a 24-years sailing career, she was caught in a Cape Horn storm that tore down her masts and ended her career as a cargo ship. Rather than re-rigging her, her owners sold her for use as a floating warehouse in Punta Arenas, Chile. She was first converted to a floating warehouse and then to a sand barge in South America, where waterfront workers referred to her as “el gran Valero,” the great sailing ship, because even without her masts she was recognizable as a sailing ship.

In one sense, Wavertree exists today because of what, in hindsight, were a series of fortunate accidents. Her dismasting ended her career as a sailer, but her hull was sound so she didn’t end up like many of her sisters––lost to sinking, wrecked during a gale, or sold for the value of scrap. Instead, she was repurposed twice and then, at the end of her useful life in those adaptations, she was found just in time by famed ship preservationist and founder of San Francisco Maritime Museum Karl Kortum (1917–1996). It was he who sent a telegram to New York in 1968 to notify the fledgling South Street Seaport Museum that a great windjammer had been found for the fleet. She was purchased for scrap value, made sufficiently sea-worthy, and taken in tow, bound for her new home at South Street.

On August 11, 1970, she arrived in New York in a parade of fireboats, tugs, and ferries, with helicopters hovering overhead. Today, Wavertree is visited by guests of all ages from around the globe and serves as the centerpiece of the “Street of Ships” at the Museum. She was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 13, 1978 and symbolizes the profound influence of sailing ships, their intrepid sailors, and the bustling waterfront in shaping New York City into a modern metropolis. As a historic vessel with a fascinating past, Wavertree embodies the rich maritime heritage that played a pivotal role in transforming South Street into the vibrant heart of “Where New York Begins.”

24-Years of Sailing

Thomas Herman Wilton (Swedish-American, 1850-1928). “Wavertree lying at anchor in San Francisco” n.d. (original ca. 1899). South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

From 1885 to 1910, Wavertree circumnavigated the globe at least three times carrying bulk cargoes to distant ports. She carried grain from Australia, nitrate from Chile, lumber from the west coast of the United States, and jute from modern-day Bangladesh. She called at ports all around the world, including: European ports in Ireland, Germany, France, and Belgium; South American ports in Peru, Chile, Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina; South African and South East Asian ports in Sri Lanka, India, Burma, and Singapore; Australia; and North American ports in both Canada and the United States—including the states of California, Oregon, Washington, and here in New York in 1895.

Ships like Wavertree were ideal for carrying such bulk and commodity cargoes. Although steamships were taking over many routes, the long ocean voyages with low-profit bulk cargoes remained the domain of the sailing ship. The Chilean nitrate trade was especially unchanged with the introduction of steamships as this trade route required ships to travel enormous distances, which was impractical for the steamers of the day.

A rise in industrialization produced a greater need for raw materials to be shipped around the world in the 19th century. Iron ships such as Wavertree had the capacity to do that job. In the years between 1875 and 1900, the tonnage carried by commercial sailing ships doubled to meet the demands of the rapidly globalizing economy.

[Portrait of Capt. William Masson and crew of tall ship Wavertree in Portland, Oregon], 1907. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

The ship’s crew generally consisted of men from economically poor regions of the world for whom employment aboard a sailing vessel was not an adventure, but a necessity. The crew members worked long days tending to the needs of the ship for low pay. Broken limbs were common and, as there were usually neither trained medical professionals nor professional medical instruments on board, remedies for injuries and illnesses were often makeshift. At times, the work was tedious and treacherous, and the living conditions crowded and dangerous. Thus, good morale was essential.

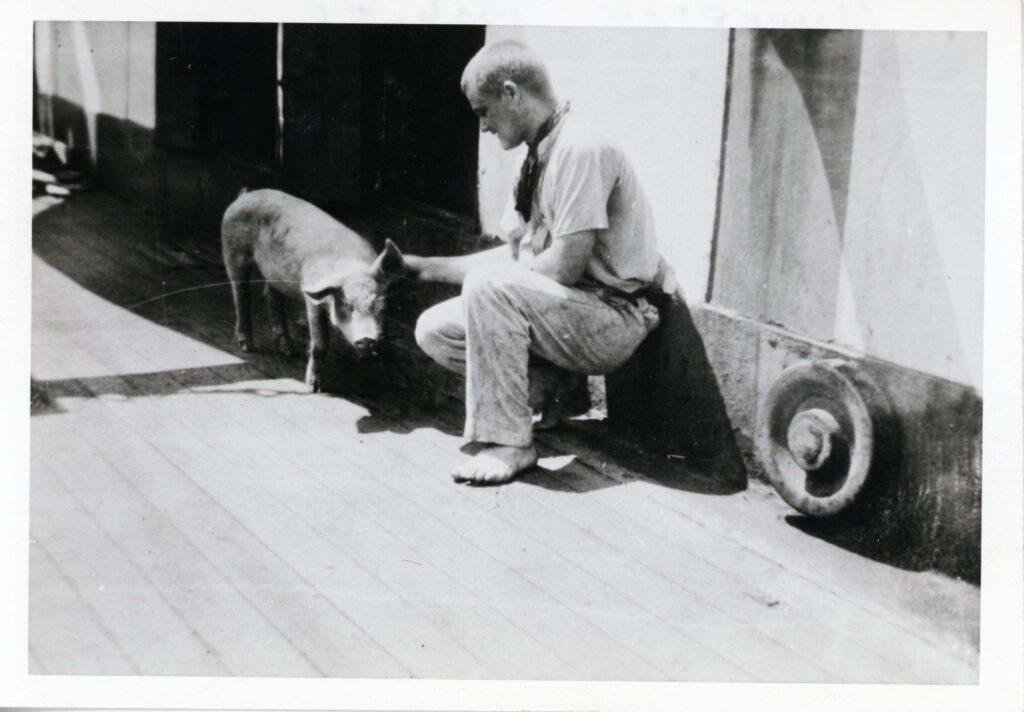

Animals on board served as mascots for the ship. Dogs and cats were some of the most common, helping to fight off pests. However, some ships carried more unusual animals such as monkeys, polar bears, or pigs as their mascots, as can be seen as a crew member of Wavertree’s sistership Milverton plays with the pet pig on board.[3]“The British Navy Has a Long History of Adopting Animal Mascots.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 10, … Continue reading

[Crew member with pig onboard the ship Milverton], ca. 1924-1925. Gift of Lars Grönstrand, South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Though the work of the crew was tough, there were some moments of levity. Many stories of life aboard Wavertree come from the narrative of Captain George Spiers (1889–1971) who sailed with the ship as a teenager at the beginning of his 48-year career. Spiers published his account in Wavertree—An Ocean Wanderer in 1969, a book that artfully combines events that occurred during his Wavertree voyages with what may be fantastical sailor’s yarns.

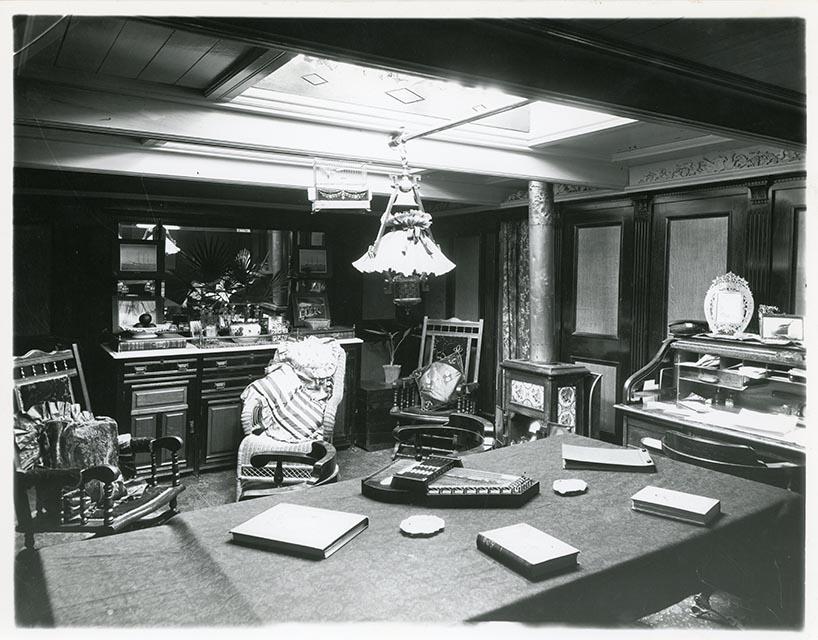

According to Spiers, Captain William J. Masson, the last captain from the R. W. Leyland & Company, once nailed a Union Jack to the ship’s ladder, and the Chilean police, who wanted to board to question the crew about a series of robberies on shore, were so surprised by the prospect of walking on the symbol of the British Empire that they turned and ran. Spiers also recounted that a third mate bragged that he could paint the royal yard on the mizzen mast without splattering on the deck below. He dropped the entire can, which crashed through the skylight into the captain’s saloon.

Left: “Eva Montgomery’s captain saloon”, n.d. San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, U60.12500

Right: “Wavertree‘s captain saloon” 2023.

The cabin under her poop deck—the saloon—was opulently decorated in the Victorian style. It was the captain’s living room and the ship’s office and would have been full of the smells of pipe tobacco, kerosene oil, and fresh, hot tea. Plush carpets, fancy furniture, book-lined shelves, and pictures in ornate frames might let you forget, at least for a moment, that you were on a ship.

Wavertree’s sole purpose was to carry cargo for hire. As a tramp—a ship that took any cargo that paid to any port—Wavertree’s saloon operated as a ship’s office in port and as a parlor at sea. Here, the captain would meet with ship’s agents, port officials, insurance representatives, and clients with goods to sell, buy, or have shipped. The presentation of the saloon was a credit both to the Master of the ship and to the company.

There are few original images and artifacts from Wavertree when she was in service. What you currently see in the captain’s saloon space is a credible and ever-growing interpretation of a Victorian era cargo sailing ship of the late 19th century––including a portrait of the reigning monarch. The more fragile items would be stowed while voyaging to protect them during rough seas and taken out when the ship made port.

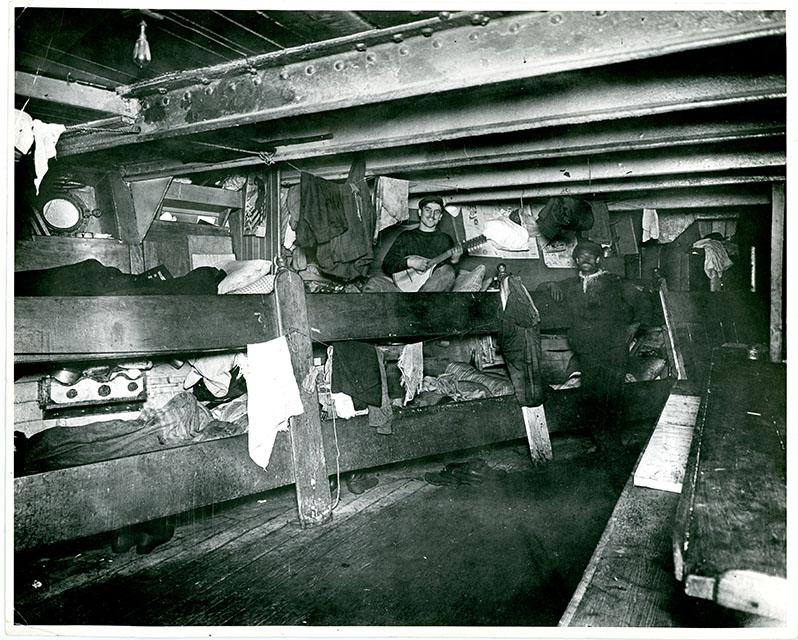

Left: [Men posing in an unidentified ship’s crew quarters], ca. 1900. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Right: “Wavertree‘s foc’s’le” 2023.

Unlike the elegant coziness of the saloon aft, the forecastle (pronounced ˈfōksəl) or crew’s quarters (sometimes referred to as a bunkhouse or Liverpool house) were sparse. Inside there were 20 bunks for seamen, a communal table and benches, and a small stove that offered little relief from frigid temperatures and damp conditions. The sea intruded, spilling over the coamings and dripping from the boots and oilskins (waterproof clothing) of sailors, wetting bunks and clothing. Seamen lived and worked by a 24-hour watch schedule of four hours on duty and four hours off. However, the needs of the ship came first and, in heavy weather, those “off watch” would frequently be called to help with work on deck, cutting into already meager rest time.

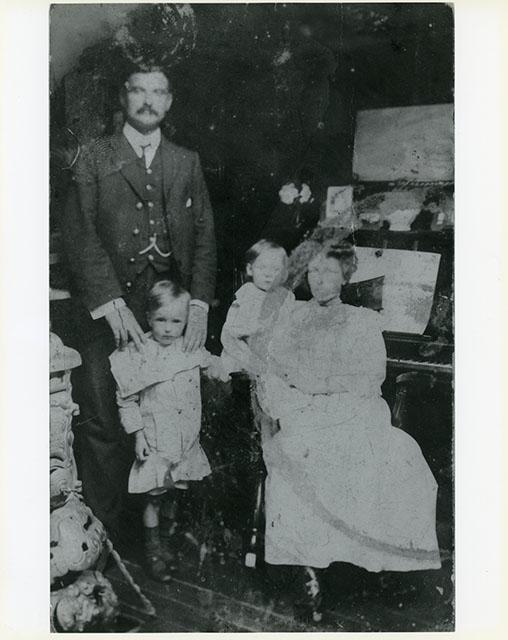

It was not uncommon for the ship’s Master to bring his family aboard. With many voyages lasting months or years, the only way to keep the family together was to bring them on the journey.

The captain’s family lived aft, in the cabins off of the saloon, and dined with the captain. Children were occasionally born at sea and, in these cases, often spent their formative years away from land.

While captain’s wives typically had no official duties, there are a number of examples of women learning navigation, and in one case even taking command of the ship after the captain had fallen ill.[4]Mary Ann Brown Patten (1837–1861) became the first female commander of an American merchant vessel when her husband, the captain of clipper ship Neptune’s Car, collapsed during an 1856 … Continue reading

[Portrait of Capt. William J. Masson and family in Wavertree’s captain’s saloon], ca. 1906. Gift of W.J.L. Masson, South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

The 1910 Storm

Though Wavertree is unique today, as the last remaining iron-hulled three-masted full-rigged cargo ship in the world, she wasn’t particularly unusual during her sailing career. Wavertree was one of hundreds of square-rigged sailing ships that sailed the oceans carrying cargo from port to port. Though dramatic events occurred during her sailing career, including a fire, deaths at sea, and a near miss during “The Great Gale of 1902,” they were considered common occurrences in the risky life of a windjammer. Even Wavertree’s dismasting off Cape Horn was not unusual.

The waters south of Cape Horn, the Drake Passage, connect the Southern Oceans and are, perhaps, the most consistently violent bodies of water in the world.. Before the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the only way to sail between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was to go around the southern tip of South America. The route combines strong winds and currents, as well as frigid waters with risk of icebergs. Hundreds of ships have met their end in the Drake Passage.

Wavertree had completed earlier voyages around Cape Horn, but her luck wouldn’t hold through 1910. The ship departed Cardiff, United Kingdom, on June 16 of that year with a cargo of coal bound for Talcahuano, Chile. Arriving in August, her attempt to round Cape Horn did not go well. The January 1911 issue of The Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper stated:

“Sailing ships going round Cape Horn usually have rather a thrilling time, but the experiences of the “Wavertree” are of unusual interest. The “Wavertree,” a large vessel of 2100 tons gross, left Cardiff on June 16th for Talcahuna. When 58 days out she was 200 miles south of Cape Horn, when a violent gale caused her to carry away nearly all her sails. Being practically without canvas, she was unable to proceed on her voyage, but had to run back to Monte Video. There she was refitted and left that port with practically a fresh crew.”

The same article goes on to describe Wavertree’s second attempt around Cape Horn, which was even more disastrous:

“At the beginning of December the ship unfortunately had very bad weather. The hurricane (‘the real thing’ as one of the crew graphically described it) was so severe that the mainmast snapped in two almost flush with the deck and smashed two life boats and the main pump. The wreckage tore holes in the deck, and through these a great volume of water poured into the lower parts of the ship. And this led to an even more serious calamity.

[…] A heavy sea swept the men off their feet and smashed them against the wreckage that was everywhere strewing the deck. So violently were the men hurled by the sea that three of them had their legs broken, one had his leg severely wounded and two ribs of another was fractured. Trouble upon trouble apparently came upon the unfortunate ship: the fore topmast came down from aloft and did further damage to the deck, while shortly afterwards the mizzen topmast was carried away. This ship was now helpless and fortunately for the crew drifted towards the Falklands. She was towed in from near the lighthouse to Stanley on December 2[illegible]th by the “Samson.”…”[5]From “Sailing Ships Visiting Port Stanley“, Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper, January 1911. Jane Cameron National Archives, Falkland Islands.

[Wavertree dismasted, looking aft] n.d. (original ca. 1910-1911). Gift of Joe King and Stanley Senior School Photography Club, Falkland Islands, 2018.002.0002

The Re-Discovery

When Wavertree was discovered in 1966 by Karl Kortum (1917–1996), founder of what is now the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, she was serving as a sand barge in Buenos Aires, Argentina under the name Don Ariano N. Don Alfredo Numeriani (born 1897) of Buenos Aires had bought Wavertree in 1948 and renamed her after his father, Don Ariano Numeriani. The tall ship was known as “Don Ariano N.” from 1948 to 1968.

Kortum recounted his introduction with Wavertree in a Sea History magazine article from 1981:

“Who was she? I quickened my pace until I was abreast, separated only by the oily and Styx-like waters of the Riachuelo. Where brass letters spelling a name had once attached to her beakhead now only rivet holes and faint strokes of corrosion remained. But a pattern could be coaxed out of these graffiti—W…a V, a T, a recurring E. I played anagrams with the gaps. W-A-V-E-R-T-R-E-E. Wavertree!”

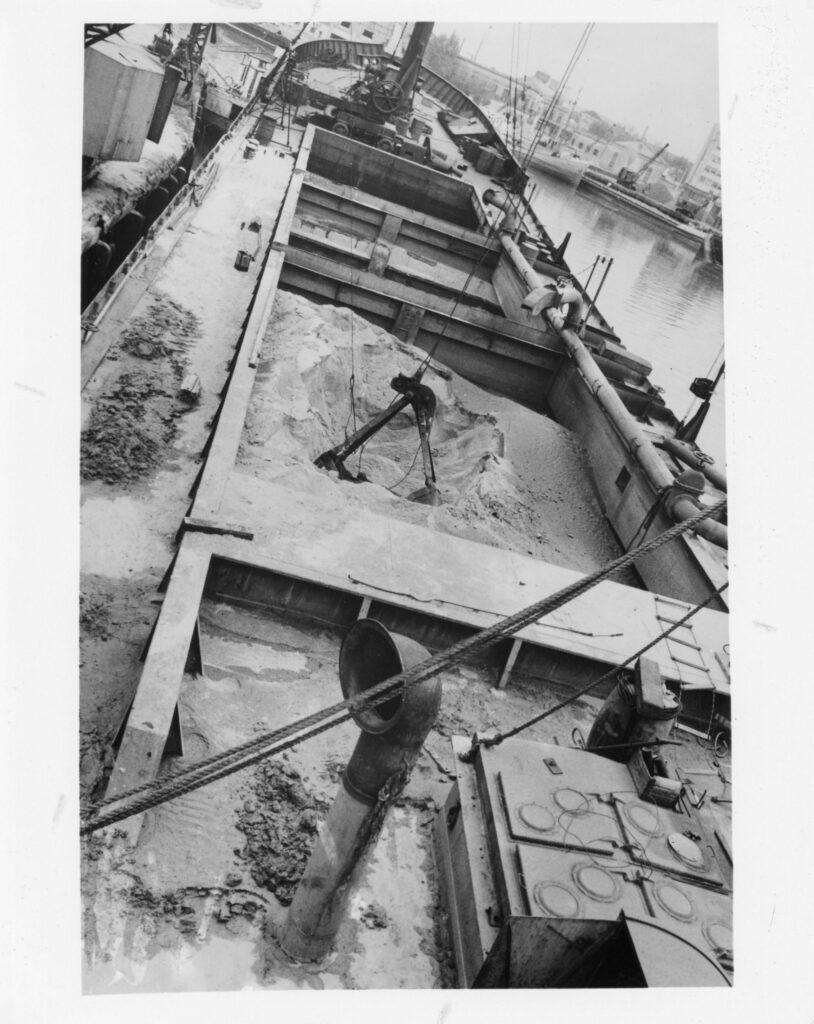

Four years later in 1970, Wavertree arrived in New York—75 years after it first came to New York port, carrying nitrate from Chile. The deck was restored so that the cargo holds are covered, not open as they appear in this photograph from 1967 with exposed sand.

“Wavertree as a sand barge in Buenos Aires”, ca. 1967. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

New York City Life

By the time Wavertree was built, she was nearly obsolete. Steam engines suitable for efficiently propelling ships across the ocean had been introduced in the 1870s and were being used on nearly all the shorter trade routes. Most countries stopped building large sailing ships altogether in the first decades of the 20th century.

The century-old Wavertree, built of riveted wrought iron, is an archetype of the sailing cargo ships of the latter half of the 19th century that, during the “age of sail,” lined South Street by the dozens, creating a forest of masts from the Battery to the Brooklyn Bridge.

Gerlot W. Schmidt, photographer. [View of Wavertree being towed to the South Street Seaport Museum with tug alongside], August 11, 1970. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Seaport Museum founder Peter Stanford wrote about Wavertree’s return for Historic Preservation, comparing the ship’s commonplace career to her extraordinary survival into the mid-20th century, stating:

“In 1895, before airplanes, radios, television or even the Spanish-American War had occurred a full-rigged sailing ship—one of a dying breed—left New York harbor. Her name was Wavertree. She had arrived in January of that year, bringing nitrate from Chile; when she left for Calcutta on March 21, carrying case oil (cans of kerosene boxed in wooden cases), her departure went unnoticed. Seventy-five years later the Wavertree returned to New York. Mayor John Lindsay proclaimed August 11, 1970, ‘Wavertree Day’ in honor of her arrival.”

All images: Gerlot W. Schmidt, photographer. [View of Wavertree being towed to the South Street Seaport Museum], August 11, 1970. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

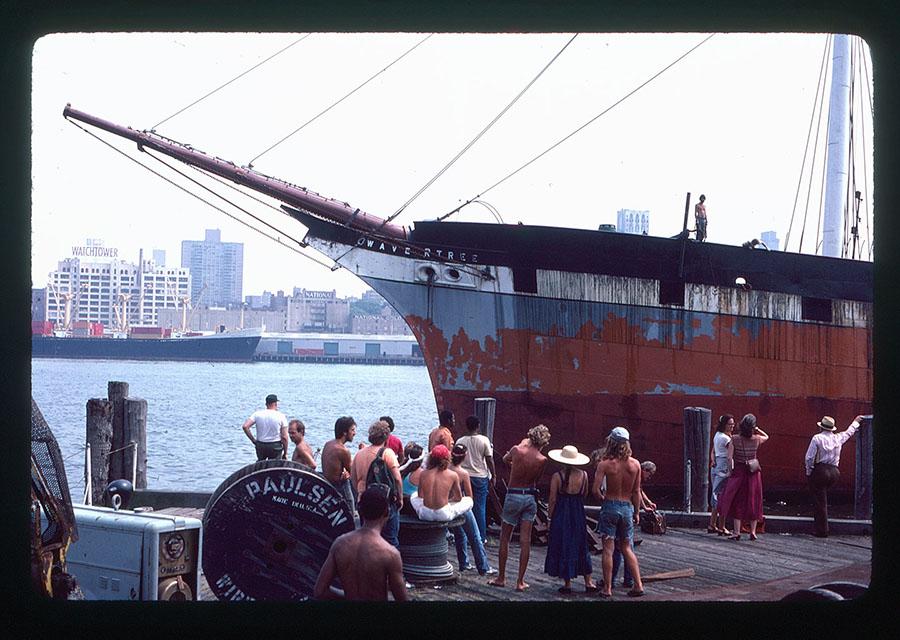

In the early years of the South Street Seaport Museum, a group of passionate New Yorkers became the Museum’s first volunteers, and laid the foundation for the work the Museum does today in sharing the incredible story of the rise of the port of New York with our visitors and community.

Waterfront volunteers continue to support every aspect of preserving the Seaport Museum’s ships. The crew worked and still works to restore and maintain the fleet of historic vessels using traditional maritime skills while enjoying the unique atmosphere of a busy waterfront that makes the South Street Seaport Historic District so special.

Left: [Volunteers and visitors watching the 1885 tall ship Wavertree from South Street Pier], August 1981. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

Right: Image credit Richard Bowditch.

Wavertree as an Event Space

Wavertree is the perfect setting for your next event and features two open decks and accommodations for food service and audio/video hookups. This historic ship provides a memorable setting with unparalleled views of the Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan skyline, and is ideal for any special occasion—large or small. Ask us about concerts, fundraisers, cocktail parties and more.

Additional reading and resources, on Wavertree, traditional square-rigged ships, and Cape Horn

“Barons of the Sea: And Their Race to Build the World’s Fastest Clipper Ship” by Steven Ujifusa, 2018.

“A Dream of Tall Ships” by Peter & Norma Stanford, 2013.

“The Last Time Around Cape Horn: The Historic 1949 Voyage of the Windjammer Pamir” by William F. Stark and Peter Stark, 2003.

“The Peking Battles Cape Horn” by Irving Johnson, 1997.

“The War with Cape Horn” by Alan Villiers and Adrian Small, 1971.

“Wavertree: An Ocean Wanderer” by George Spiers, 1969.

References

| ↑1 | The intended name for the ship that would become Southgate, and later Wavertree, was Toxteth. This name was used in correspondence between Leyland and Oswald, Mordaunt and Co. as the ship was built; from “Champion of Sail : R. W. Leyland and his Shipping Line” by David Walker, 1986, pp. 159-161. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”A ship that regularly sails on a fixed route following a schedule is known as a liner. This is because they have regular ports of call. On the other hand, we have ships that do not follow a schedule or have regular routes. Such ships are called tramp services. Typically, tramp services are designed to transport cargo, while liner services cater to cargo and passengers separately.”; from “What Are Liner Services and Tramp Shipping?” by Hari Menon, Marine Insight, August 20, 2021. |

| ↑3 | “The British Navy Has a Long History of Adopting Animal Mascots.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 10, 2015: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/animal-mascots-once-sailed-navy-180957508/ |

| ↑4 | Mary Ann Brown Patten (1837–1861) became the first female commander of an American merchant vessel when her husband, the captain of clipper ship Neptune’s Car, collapsed during an 1856 voyage.; from “Mary Ann Brown Patten” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. |

| ↑5 | From “Sailing Ships Visiting Port Stanley“, Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper, January 1911. Jane Cameron National Archives, Falkland Islands. |