Digging into the past—literally

A Seaport Museum Blog

by Meghan L. DeVito, Grants and Research Manager

September 2, 2021

Hello! I’m the Grants and Research Manager here at the South Street Seaport Museum, where I’ve worked in the Development Department for the last 6+ years. Much of my work during this time has involved writing grants for the restoration of the Museum’s National Historic Landmark and National Register-listed ships and buildings, and as is the case with many of my co-workers, my background is in a field that supports to the work we do here. That’s part of what makes working at the Seaport Museum so interesting—collaborating with professionals from a variety of fields due to the multidisciplinary nature of our work. I myself have an education and background in archaeology, having worked as a professional archaeologist on and off in different capacities for the past 14 years.

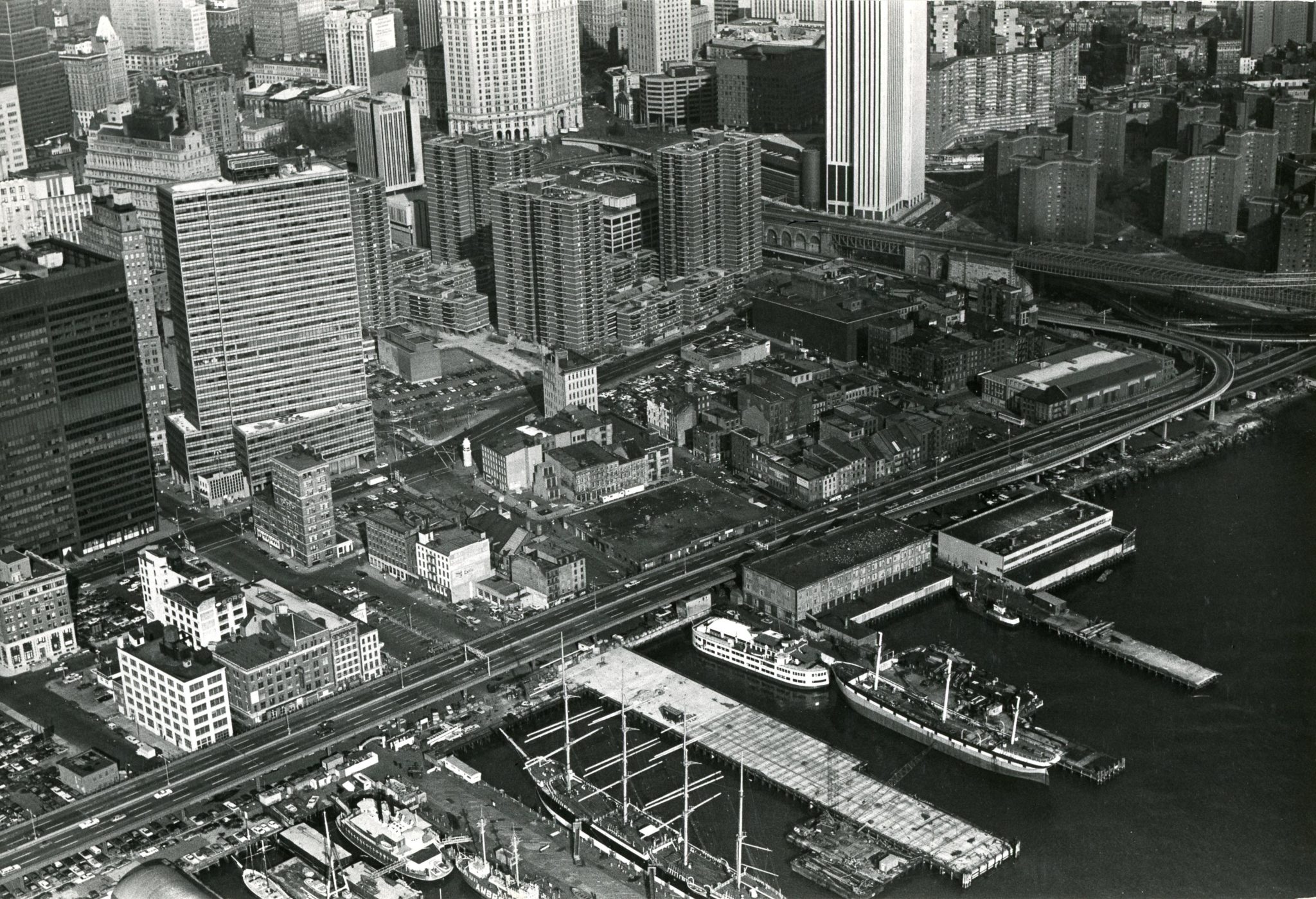

The South Street Seaport Historic District, in which the Museum is located, is known for its cobbled streets and historic buildings representing “the last architectural vestige of New York’s 18th and 19th century mercantile waterfront.”[1] A Billion-Dollar Battle Over a Parking Lot at the Seaport by Michael Kimmelman, New York Times, April 27, 2021. But few people know that this area is also full of archaeological materials related to the growth of New York City into a global financial powerhouse and a crossroads of world cultures. Archaeology offers a unique kind of evidence about this fascinating time in our City’s history.

What is archaeology and how does it work?

Archaeology is a broad field of study that can be hard to define, but it is generally considered to be the study of the human past through cultural materials left behind, often buried in the ground for hundreds or thousands of years. I always like to say that archaeology is about as close as one can get to time travel—there is nothing like the feeling of being the first person to see or touch an artifact since the time it was deposited in the ground. You feel a direct human connection to the past through material culture that cannot be replicated elsewhere. But archeology is much more than finding interesting artifacts in the ground, and archaeologists do not just start digging to see what they can find. Archaeology begins with research questions, involves documentary research, and fosters collaborations with other types of scientists and researchers like geologists, biologists, and historians.

Much of the archaeology conducted in the United States today is called cultural resource management and is carried out in accordance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. This law mandates that archaeological testing be conducted on any construction or infrastructure project that involves federal permits or federal funding to ensure that any cultural resources are protected and studied, not destroyed.

Urban archaeology, or the study of cities through archaeological means, began to emerge as a subgenre of archaeology as recently as the 1970s, during a period when Americans felt a heightened concern for preserving their shared cultural heritage at national, state, and local levels, often passing laws to do so. It was during this time that grassroots historic preservationists in New York were working to save treasures of the City’s architectural heritage from urban renewal practices which were leveling entire neighborhoods. In fact, what is now the South Street Seaport Historic District is one of those neighborhoods rescued from the wrecking ball by individuals who went on to found our Museum. Interest in archaeological research was a part of this historic preservation movement. In fact, the 1965 NYC Landmarks Law, passed to protect the city’s architectural heritage, inadvertently triggered the first large-scale archaeological investigation in New York City, when a developer agreed to conduct archaeological testing in lieu of reconstructing the façade of a 17th century structure that had been removed from the development site.[2]Urban Archaeology, Municipal Government, and Local Planning: Preserving Heritage Within the Commonwealth of Nations and the United States, edited by Sherene Baugher, Douglas R. Appler, William Moss, … Continue reading That site, Stadt Huys, and the wealth of information recovered from it about New York’s colonial past, helped prove that cultural resources could survive even in an urban setting as continuously developed and redeveloped as the Financial District. It brought New York City—and particularly Lower Manhattan—to the forefront of this new field of the study of cities.

Archaeology in the Seaport

Archaeology in the Seaport offers a unique window into the past where we can see the young city as it grew, what challenges people faced and how they dealt with them, and what life was like for previous generations of New Yorkers. As you’ll read below, much of the archaeology that has taken place here reveals the process of landmaking in the 18th century. These techniques were often not recorded, so archaeology offers one of the only ways we can learn about how the city grew and the vernacular techniques and technologies involved. Considering the buildings of the Seaport still stand solidly on this human-made land, we owe much to these early urban planners and engineers!

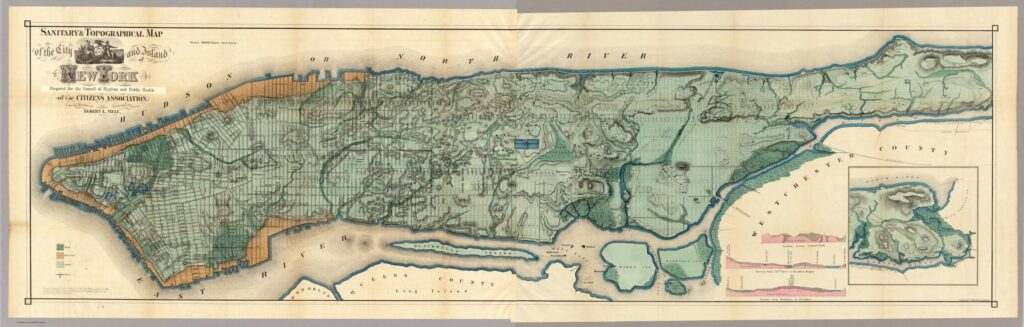

The shoreline along the East River in Lower Manhattan did not always look as it does today. Clues can be found in the street names such as Water Street, which is a full two blocks from the water’s edge, as well as in historic maps. From the time when New York was a Dutch colony, people were manipulating and expanding the shoreline to suit their needs. In the 1865 map below, the orange sections show how much of the shoreline of Manhattan was made land by that time.

Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York, 1865, by Egbert L. Viele. Courtesy of the David Rumsey. Historical Map Collection.

By going back and comparing older maps, one can trace how and when each part of this new shoreline was filled in. This is the work archaeologists do before they dig. They will also trace the ownership of the property they’re working on, and in the Seaport that involves researching who received water lot grants to fill in the land. Water lots were parcels of waterfront real estate sold by the city and required to be filled in by their new owners (at their own expense). This new land became some of the city’s most valuable and versatile real estate, and merchants could construct it to suit their needs. It also brought the shoreline out to deeper waters so that ships could tie up to piers directly instead of anchoring offshore and having to unload their goods from there.[3] Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001, pp. 225-226.

Owners of water lots were resourceful when making new land and employed a variety of techniques and unwanted materials for this process. Dirt from leveling nearby land, trash, and debris from razed buildings were all used to fill in water lots. Wharves, bulkheads, and cribbing (essentially large boxes made of logs tied together, sunk and filled with refuse) were used to retain the newly made land as it was being filled in. Archaeologists often find the remains of these substantial structures, as well as other creative methods people used to create new land, as you’ll see below.

209 Water Street – A Hidden Ship at South Street

Several of the Seaport Museum’s buildings themselves have been the subject of archaeological investigations. In 1978, the Museum wanted to install a sump pump in the basement of 209 Water Street, next to the newly established Bowne & Co. Stationers, due to ongoing flooding issues in the building’s basement. When it became apparent that the amount of digging for this project would be more than anticipated and that cultural material might be disturbed, archaeologists from City College were called in to monitor the digging. What they discovered would help shed light on landmaking practices in the area.

Maps of the area drawn in the 18th century indicated that the land that 209 Water Street stands on was filled no earlier than 1755, with the landmaking process ending sometime between 1767-1789. This meant that archaeologists expected they would be excavating and studying 18th century landfill, and indeed, the artifacts they found were representative of daily life in New York in the 18th century and included gin and wine bottles, clay pipes, shoe leather, many types of ceramics of mostly British manufacture, and even two coins—a George III farthing dating between 1771-1774, and a George II shilling possibly dating between 1727-1760.[4] The Water Street Site: Final Report on 209 Water Street by Roselle Henn, 1978, pp. 158-162. But it was one large artifact that captivated archaeologists and staff at the Seaport Museum the most.

Excavation of a ship at 209 Water Street, 1978. Photo by Norman Brouwer. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

As digging progressed, a group of wooden planks were discovered, which were initially thought to be part of the cribbing used to hold landfill in place. However, it soon became apparent that it was the frame of a ship that had been incorporated into the landfill. The ship was examined by the Museum’s historian at the time, Norman Brouwer, along with a naval architect and a maritime archaeologist.

A few of the planks were removed for closer inspection. The remains of the ship were in an excellent state, preserved by the water-logged soil they had been in, and several features of the ship could still be identified.

The ship’s treenail (wooden “nail” or dowel) construction method was still identifiable, and several knees (braces) were still articulated with the ship’s frames and beams.

The exterior of the hull was identified by a coating of tar and horsehair, which was commonly applied to the outer planking of ships to protect them from worms, particularly for ships sailing in the tropics. [5] The Ship in Our Cellar by Norman Brouwer, Seaport Magazine, Fall 1980, p. 22.

Based on the size of the timbers used in its construction, the ship was estimated to have been 80-100’ long, with a displacement of about 200 tons. [6] The Water Street Site: Final Report on 209 Water Street by Roselle Henn, 1978, p. 8.

The ship was quickly recognized by everyone involved in the excavation as an extremely important cultural resource; very few 18th century ships have been found in the United States, and as a result most of what we know about 18th century shipbuilding is from documentary resources, not actual examples.

Planks recovered from the ship under 209 Water Street, 1978. Photo by Norman Brouwer. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

After consulting with the President’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, the National Park Service’s National Register Unit, and the New York State Dept. of Historic Preservation, the Museum decided that the ship under 209 Water Street should be reburied and preserved in situ until such time when the Museum had the resources to conduct a formal, full-scale excavation. The Museum considered the ship and its research potential to be an extremely important asset to telling the story of the Seaport’s earliest days.[7] The Ship in Our Cellar by Norman Brouwer, Seaport Magazine, Fall 1980, p. 23.

Ship components from the excavation at 209 Water Street, 1978. Photo by Norman Brouwer. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

199 Water Street – The Telco Block

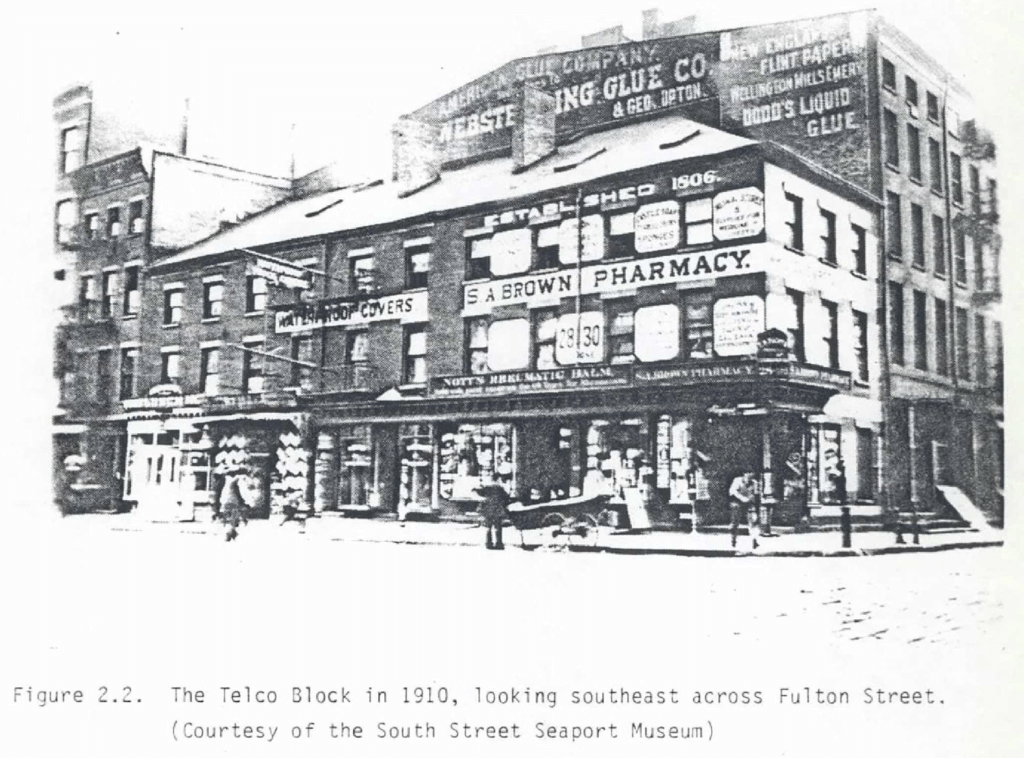

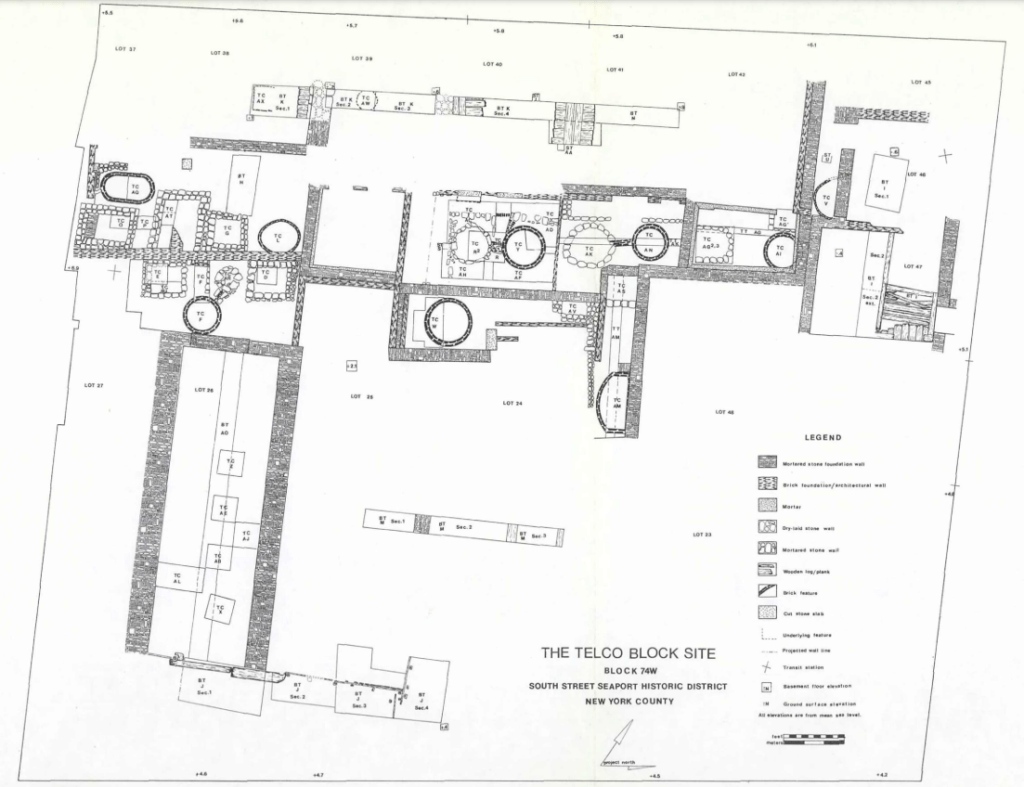

Moving south along Water Street we come to 199 Water Street, and the site known as the Telco Block. The Telco Block was a large-scale excavation in 1981 taking up almost an entire city block. It is a site well-known by archaeologists for the wealth of information it provided about the changing development of the seaport, and health and sanitation in mid-19th century New York.

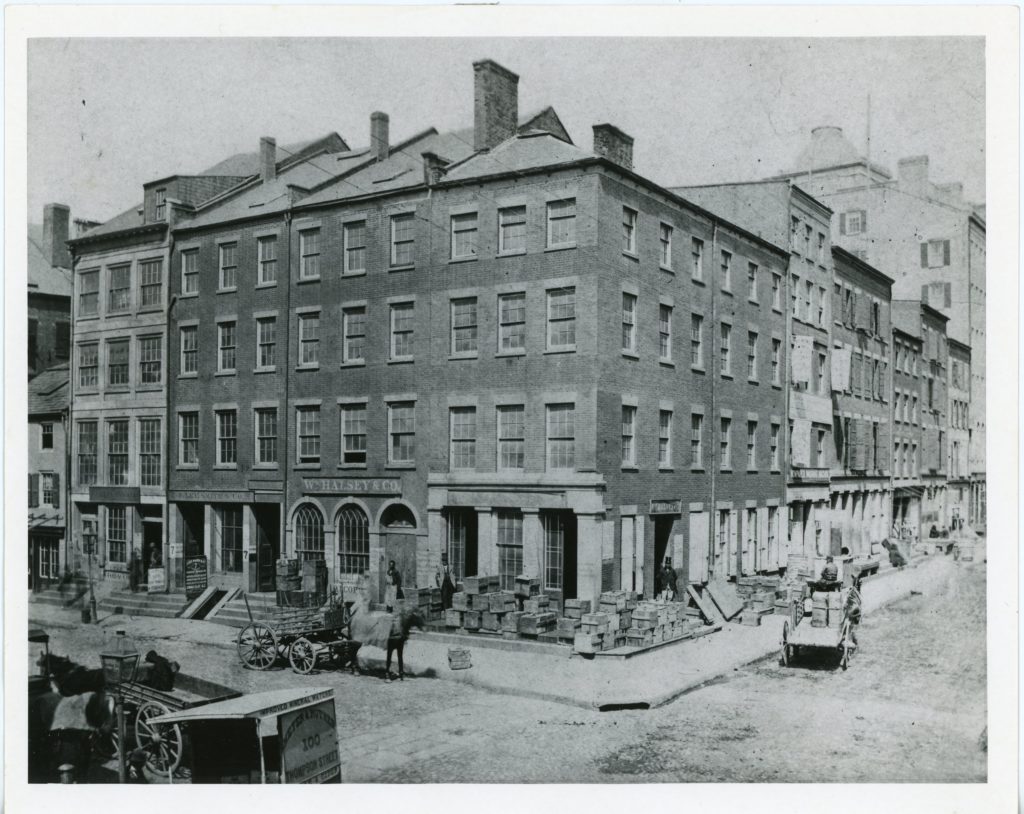

While a large office building now stands at 199 Water Street, the block once looked similar to the Schermerhorn Row block, with 19th century brick commercial buildings filling the block. As with the rest of the Seaport, the land of the Telco Block was made with 18th century landfill, and the block has been continuously occupied from the time the land was made. There is archaeological evidence of all phases of the Seaport’s development—from the creation of the land, to the first mixed commercial-and residential-use buildings, to the switch to strictly commercial use in the early 19th century, and finally to the change in the type of commercial enterprises the buildings housed in the mid-19th century.

Since it was determined that the construction of the new large office building would destroy the potential archaeological resources of the block, and since federal funds were used in the construction of the office tower, archaeological excavation of the site was mandated under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.[8] The Archaeological Investigation of The Telco Block, South Street Seaport Historic District, New York, New York, Prepared by Diana Rockman, Wendy Harris, and Jed Levin, p. 2.

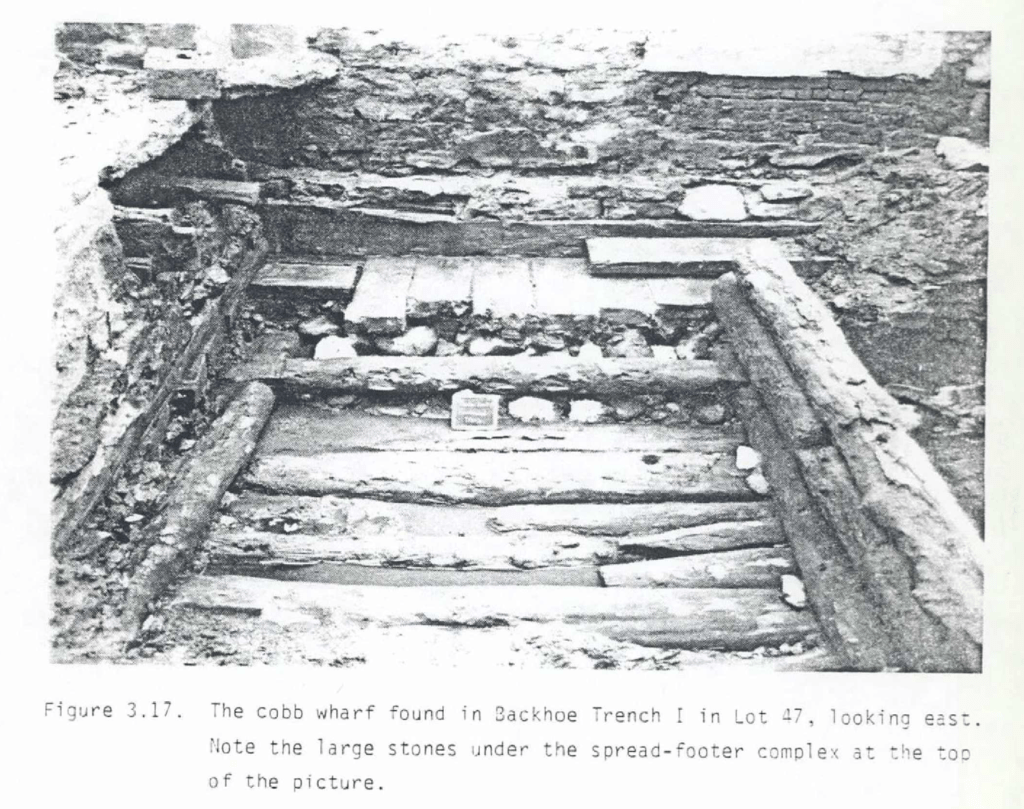

The findings at the Telco site can be divided into two kinds: those that tell us about how the land was created, and those that tell us about people living and working on that land. The excavations took place in the landfill of six original water lots; they contained wharves and bulkheads which were used to help retain the landfill and which correlate to structures found in historic documents and maps.[9] The Archaeological Investigation of The Telco Block, South Street Seaport Historic District, New York, New York, Prepared by Diana Rockman, Wendy Harris, and Jed Levin, p. 72.

As a result of the initial documentary research of this site, archaeologists believed that some of the architectural remains of the building would still be intact, including features like cisterns (to collect rainwater) and privies (outhouses) located in the backyards of the old buildings. This proved to be correct, and in all, eleven privies and eight cisterns were uncovered, as were an oven flue, a dry well, a wooden box, a wooden barrel, and a wooden floor. Archaeologists like to study features like privies and cisterns because household trash was often thrown in them, and because their construction is not recorded in historical documents, so studying the physical remains is the only way to learn about them.[10] Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001, p. 248. In the case of the Telco Block, it was not just what was in these features that was interesting, but also their placement in the backyards of the buildings that once stood there.

A fire in 1816 destroyed the original buildings of the Telco Block, and since land was always a commodity in New York City, when the landowners rebuilt, they built their buildings as large as they could to get the most value out of them. This meant extending them back on the lot (New Yorkers were not building skyscrapers yet, and indeed, Schermerhorn Row was a large private building project for its time.) This left only small strips of land on which to build privies and cisterns—necessary utility structures. The Telco Block excavations revealed just how little land these structures were built on, and their placement revealed clues about health and sanitation issues Newyorkers faced in the early-mid 19th century.

Telco Block Site Plan showing how close together privies and cisterns were built.

Due to the limited space, privies and cisterns in the backyards of the buildings in the Telco Block were built next to one another. This meant that human waste from the privies could easily leech out and contaminate the nearby drinking water in the cisterns. In the mid-18th century, soon after these structures were built, New York City was facing a public health crisis, with a series of cholera epidemics killing thousands of residents. The structures uncovered in the backyards of the Telco Block provide physical evidence of the building practices that contributed to this crisis, which ultimately led to the creation of the city’s public water and sewage systems.[11] Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001, p. 250.

175 Water Street – Another Ship at South Street

Another one of the area’s most well-known archaeological sites lies just outside of the historic district at 175 Water Street. This site captivated the public’s imagination when it was excavated in 1981-1982 due to the large ship that was found.

Like the Telco Block next to it, the site consisted of 18th century landfill, and wharves and bulkheads similar to those found at Telco were uncovered at 175 Water Street.[12] The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City, Vol. 2, 1983, p.687.. But like 209 Water Street, it is the ship that was found there that is remembered most.

Archaeologists researched the history of the site’s occupation, and it appeared that the merchants who initially owned lots at 175 Water Street collaborated on business ventures, and they may have also worked together to fill in the land in their water lots. These merchants had easy access to ships, which helps explain the discovery of a ship at 175 Water Street. In January of 1982, a wall of wooden planks was uncovered at the site, initially thought to be remains of cribbing or a bulkhead. But as was the case at 209 Water Street, that interpretation quickly changed; as excavation continued, curved wooden planks were uncovered, a telltale sign that this was a ship.

Once again, the Museum’s historian Norman Brouwer and a naval architect were brought in to examine the find. They determined that the exposed planking was the outer sheathing of the type commonly used on 17th and 18th century ships, likely making this the remains of an 18th century merchant ship. A nautical archaeologist joined the team and excavation of the ship continued, with the hope of determining the size of the vessel, how much of the inboard structure was intact, and the composition of the fill within it.

The ship was found to be more intact than most other ships of this era. While most only have the lower part of the hull intact, the Ronson ship was, in places, intact from the upper deck to the keel. By studying the structure of the ship, it was determined to have been between 72’-125’ in length.[13] The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City, Vol. 2, 1983, pp. 738-739.

It is believed that the ship found buried at the site, dubbed the Ronson after the developer who worked with archaeologists, was likely a derelict ship brought in by one of the merchants who owned a water lot to serve as cribbing for landfill. It was held in place by staggered pilings found by archaeologists and tied in place to a north-south running bulkhead off the bow and an east-west running bulkhead off the stern.[14] The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City, Vol.2, 1983, p. 692.

The ship was in an excellent state of preservation due burial below the water table for more than two hundred years and would be an excellent case study for 18th century merchant ships. Removing the entire structure was not feasible for practical reasons, cost being one of them, so a compromise was made and a 20 foot section of the bow was removed and sent away for conservation and study.

The remaining structure was extensively measured and photographed, and ultimately discarded.[15] The Ronson ship: The study of an eighteenth-century merchantman excavated in Manhattan, New York in 1982 by Warren Curtis Riess, University of New Hampshire, Durham, Winter 1987.

“Looking aft, southward over the site, with the ship’s staunch bow coming at you. Three walls were left athwart the ship to keep the sides of the excavation from caving in upon the crew at their work.” Photo by Carl Forster, courtesy of the Landmark Preservation Commission, New York City.

While archaeologists and historians at the time were unable to determine what ship this was, after decades of scholarly research the ship is now believed to be the Princess Carolina.[16]Urban Archaeology, Municipal Government, and Local Planning: Preserving Heritage Within the Commonwealth of Nations and the United States, edited by Sherene Baugher, Douglas R. Appler, William Moss, … Continue reading

One of the most important aspects of this excavation was that it was the first excavation in New York City to be opened to the public. Just as urban archaeology was an emerging subgenre of archaeology during this time, so too was so-called public archaeology, where archaeologists put an emphasis on sharing the value of archaeological heritage with the public in meaningful ways.

An “open site day” was held on February 26, 1982 at 175 Water Street where the public could watch the excavations in progress, speak with archaeologists, and tour the site.

Over 10,000 members of the public participated and the project generated a lot of good press not just for the developer, but for the potential and value of archaeological research in New York.

The John Street Lot – A Lot of Potential

(Pardon the pun.)

Today the corner of John and South Streets is an empty lot, but it once housed Federal-style buildings which completed the Schermerhorn Row Block. In 1999, when the Museum was considering constructing a new building on the lot, archaeological testing was conducted. The testing revealed evidence of a wealth of cultural material and great research potential if the site were to be fully excavated.

“View of Northeast Corner of Burling Slip at Water Street, showing 3-11 Burling Slip and 182-194 Water Street.” Late 19th century. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

As one example, the remains of a pier were found and identified as the Bowne/Byvanck pier, so-named for Everett Byvanck and Margaret Bowne, owners of the lots the pier stood between at that time. [17] Archaeological Documentary Study, Block 74, Part of Lot 20, Corner of South and John Streets, Borough of Manhattan, by Arnold Pickman, April 1999, pp. 4-5. The western portion of the pier was initially constructed prior to 1767 and the portion of the pier found at John Street represents an eastward extension which was in place by 1782. Portions of the Bowne/Byvanck pier were uncovered during both the Telco Block excavations and during archaeological testing under more western parts of Schermerhorn Row, showing that this large structure extended from what is now 199 Water Street to South Street.[18] Archaeological Documentary Study, Block 74, Part of Lot 20, Corner of South and John Streets, Borough of Manhattan, by Arnold Pickman, April 1999, p. 41.

The landfill at the John Street lot represents the final phase of the landmaking process in the Seaport. Since archaeological information has been recovered at various points along this eastward expansion of the land (under 199 Water Street and Schermerhorn Row), a more extensive investigation of the John Street lot could provide a comprehensive timeline of the landmaking process in the area. The archaeologists who tested the John Street lot felt there could still be numerous cultural resources to be found there, including artifacts deposited prior to the landfilling (either deposited from the shoreline or from docked ships); other retaining structures for the landfill, such as wharves or derelict ships; and 19th century privies and cisterns.

Since the John Street building was never realized, the materials uncovered through this archaeological testing remain in place for now, and we can only wonder at what else lies beneath the surface. One thing is for certain though: for as much as has already been uncovered about how the people who lived and worked in the Seaport adapted the landscape to suit their needs, there is still much to be discovered about this fascinating period in New York’s history.

Archaeology in the Seaport Today

All of these sites were excavated 20-30+ years ago, but that doesn’t mean that archaeology in the Seaport has stopped. Archaeological testing in the South Street Seaport Historic District, and Lower Manhattan in general, continues to be done whenever federal, state, or municipal laws dictate. A more recent example of archaeology in the Seaport is the excavations that took place along Fulton Street in 2010-2016 which yielded the ink bottles that were recently donated to the Museum’s collection. Excavations just south of the Museum’s office buildings in Burling Slip undertaken in 2009 for the construction of Imagination Playground uncovered more wharf structures, including a 190-foot section of a wharf built 1803-1807. Archaeological testing was also a part of the Thomson & Co. renovation that the Seaport Museum is currently undertaking.

This blog post provides a brief overview of some of the archaeological investigations undertaken in the Seaport, but there is so much more to learn. If you are interested in reading more about these sites and seeing artifacts from some of them, or just learning more about archaeology in our City in general, I recommend checking out the NYC Archaeological Repository. The Repository is a project of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission’s Archaeology Department. It currently houses hundreds of thousands of artifacts from archaeological sites across the city, has a searchable online database of artifacts and archaeological reports, and is open to researchers by appointment. I hope I have piqued your interest in archaeology in the Seaport, and shown what a truly special area the Seaport is and that not all of the district’s best artifacts are in the South Street Seaport Museum—some still lie beneath our feet.

Additional readings and resources

Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001.

The Ship That Held Up Wall Street, by Texas A&M University Press, 2014.

Urban Archaeology, Municipal Government, and Local Planning: Preserving Heritage Within the Commonwealth of Nations and the United States, edited by Sherene Baugher, Douglas R. Appler, William Moss, 2017.

Explore the Collections

Through the new and improved Collections Online Portal, you can explore highlights from the various collections within the Museum. Whether items are preserved in storage, displayed in Museum galleries, or on loan to fellow institutions, you can digitally discover some of these special objects in digital format.

References

| ↑1 | A Billion-Dollar Battle Over a Parking Lot at the Seaport by Michael Kimmelman, New York Times, April 27, 2021. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Urban Archaeology, Municipal Government, and Local Planning: Preserving Heritage Within the Commonwealth of Nations and the United States, edited by Sherene Baugher, Douglas R. Appler, William Moss, 2017. Chapter 12, Reflections on the New York City Archaeology Program (1980-2016) by Sherene Baugher, p. 229. |

| ↑3 | Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001, pp. 225-226. |

| ↑4 | The Water Street Site: Final Report on 209 Water Street by Roselle Henn, 1978, pp. 158-162. |

| ↑5 | The Ship in Our Cellar by Norman Brouwer, Seaport Magazine, Fall 1980, p. 22. |

| ↑6 | The Water Street Site: Final Report on 209 Water Street by Roselle Henn, 1978, p. 8. |

| ↑7 | The Ship in Our Cellar by Norman Brouwer, Seaport Magazine, Fall 1980, p. 23. |

| ↑8 | The Archaeological Investigation of The Telco Block, South Street Seaport Historic District, New York, New York, Prepared by Diana Rockman, Wendy Harris, and Jed Levin, p. 2. |

| ↑9 | The Archaeological Investigation of The Telco Block, South Street Seaport Historic District, New York, New York, Prepared by Diana Rockman, Wendy Harris, and Jed Levin, p. 72. |

| ↑10 | Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001, p. 248. |

| ↑11 | Unearthing Gotham, by Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diane Wall, 2001, p. 250. |

| ↑12 | The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City, Vol. 2, 1983, p.687. |

| ↑13 | The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City, Vol. 2, 1983, pp. 738-739. |

| ↑14 | The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City, Vol.2, 1983, p. 692. |

| ↑15 | The Ronson ship: The study of an eighteenth-century merchantman excavated in Manhattan, New York in 1982 by Warren Curtis Riess, University of New Hampshire, Durham, Winter 1987. |

| ↑16 | Urban Archaeology, Municipal Government, and Local Planning: Preserving Heritage Within the Commonwealth of Nations and the United States, edited by Sherene Baugher, Douglas R. Appler, William Moss, 2017. Chapter 12, Reflections on the New York City Archaeology Program (1980-2016) by Sherene Baugher, p. 236. |

| ↑17 | Archaeological Documentary Study, Block 74, Part of Lot 20, Corner of South and John Streets, Borough of Manhattan, by Arnold Pickman, April 1999, pp. 4-5. |

| ↑18 | Archaeological Documentary Study, Block 74, Part of Lot 20, Corner of South and John Streets, Borough of Manhattan, by Arnold Pickman, April 1999, p. 41. |