How silhouettes helped spotlight artists and lesser-known people

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

March 18, 2021

Encyclopaedia Britannica defines a silhouette as “an image or design in a single hue and tone, most usually the popular 18th- and 19th-century cut or painted profile portraits done in black on white or the reverse.”[1] Britannica Definition Silhouettes originated in Europe and were very popular there, with many surviving examples in England and France. The word apparently derived from Étienne de Silhouette, a mid-18th century French finance minister, whose hobby was the cutting of paper shadow portraits.

Silhouette-making was originally a salon activity for the privileged, carried out with a pair of embroidery scissors; but thanks to the invention of the physiognotrace by Frenchman Gilles-Louis Chrétien, in 1786, this new medium became easier, more precise, and ready to be shared outside the upper-class salon, and in popular entertainment venues, such as taverns and bathhouses.

In the United States the peak popularity of silhouettes coincided, notably, with the early years of the newly independent American republic in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Mirroring the country’s newly founded democracy, and foreshadowing how photography would soon make portraiture accessible to all, silhouettes depicted everyone including Presidents, enslaved African Americans, people with disabilities, and same-sex couples.

Professional practitioners in the 19th century included master of the genre Augustin Edouart (1789-1861), Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), and Moses Williams (ca. 1775-ca. 1825)—who had been enslaved by the Peale family and who later worked producing silhouettes at the Peale Museum as a free man[2] Once the Slave of an American Painter, Moses Williams Forged His Own Artistic Career, by Karen Chernick, on Artsy, February 19, 2018..

The art form also included self-trained artists such as the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875)[3] Hans Christian Andersen’s lesser-known talent: paper cuttings, published on DW.com and Martha Anne Honeywel (1786-1856)—a woman born without arms and only three toes, who created intricate paper cut-outs, needlework, and penmanship in works that played with contradictions between ability and disability[4]Martha Ann Honeywell: Art, Performance, and Disability in the Early Republic, by Laurel Daen, published in Journal of the Early Republic, University of Pennsylvania Press, Volume … Continue reading.

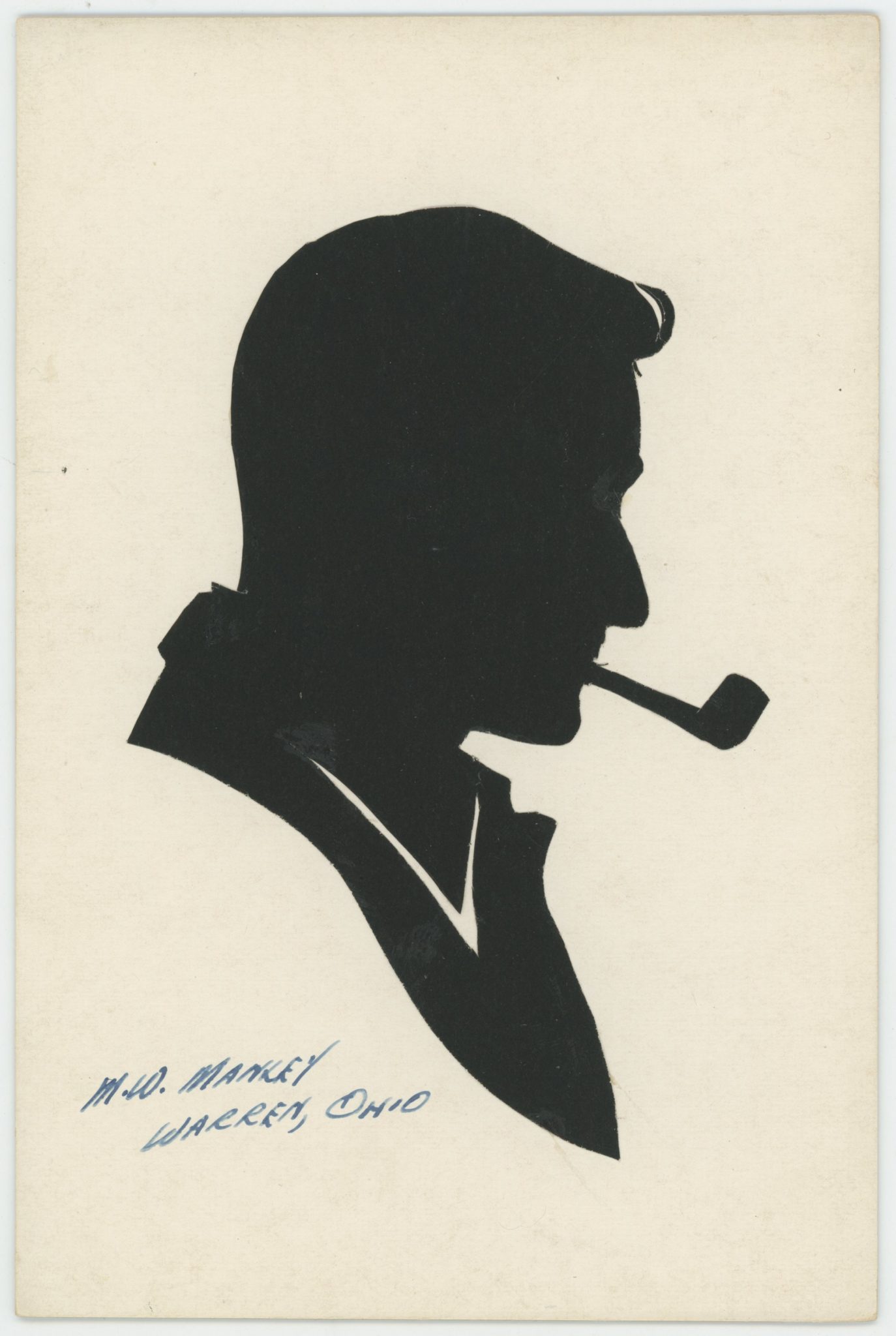

Angelica Peale Robinson. From the Album of Peale Museum Silhouettes.

Moses Williams, American, c. 1775 – c. 1825. Made at Peale’s Museum, Philadelphia.

A 2018-2019 past exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now, curated by Asma Naeem, the Portrait Gallery’s Curator of Prints, Drawings and Media Arts, featured about 50 objects that date from 1796 to today, examining historic and contemporary examples of this underappreciated medium. It was the first major museum show to examine these delicate black cut paper profiles as a significant art form.

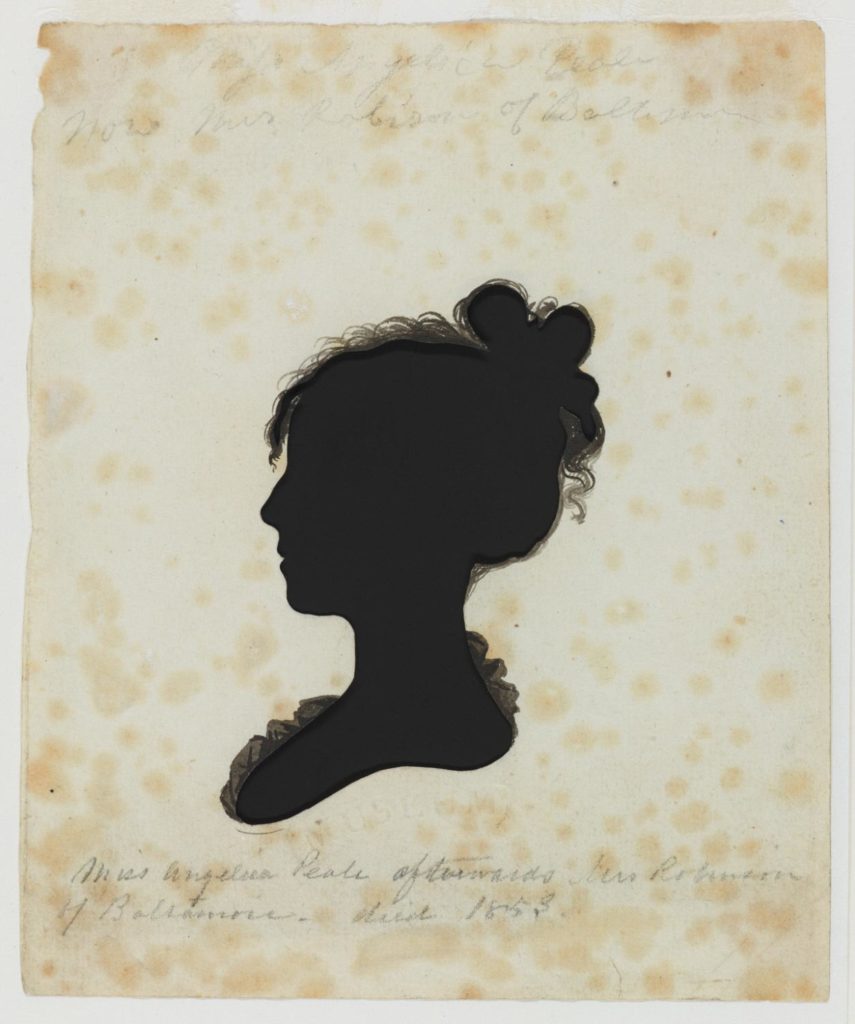

At approximately the same time that the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition opened, we here at the Seaport Museum we rediscovered a collection of 159 silhouettes, depicting World War II seamen and servicewomen in New York. The discovery happened thanks to the wall-to-wall archives and collections inventory my team and I were doing in preparation for the move of the Maritime Reference Library holdings held inside Thomson & Co., currently under renovation.

Maritime Reference Library, inside Thomson & Co., Fall 2015.

Provenance

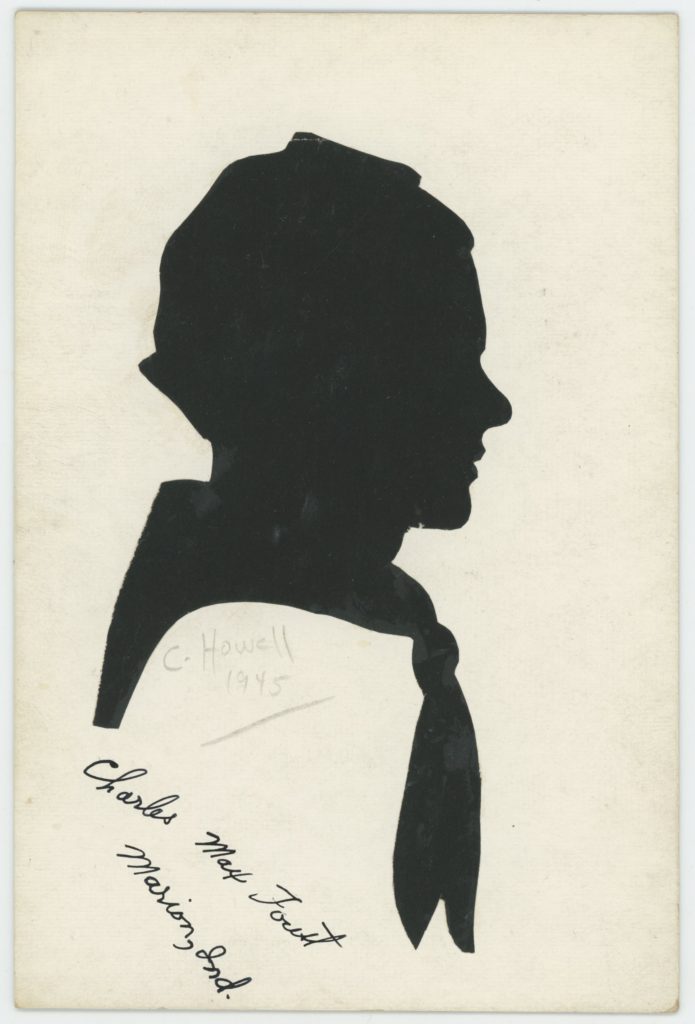

The Seaport Museum’s Conza Howell Silhouettes Collection consists of 159 hand-cut silhouette portraits made by Ms. Conza Howell (American, 1902-1987). The portraits feature U.S. Merchant Marines and other servicemen and servicewomen during World War II, and the majority of them are signed with the name and city of the subject. Based on the dates written on some of the artworks, we can say Howell made these silhouettes from 1943 to 1945.

This collection arrived at the Seaport Museum in 1989, as a transfer from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH). The collection had been offered to NMAH by Elsie Howell, sister of Conza Howell, in November 1988, but had not been accessioned, and it was determined that the South Street Seaport Museum was a more appropriate repository for the collection. Elsie Howell approved the donation and NMAH transferred the collection on February 28, 1989.

The collection was accepted by the Museum’s historian, and at time of possession the artifacts were transferred directly to the Maritime Reference Library, given an archival accession number. This archival accession number (like many others) was part of a separate accessioning system from the numbers assigned by the Collections Staff for the majority of the art collection. As such this collection was considered non-accessioned, it was not available in our database and inventory, and it was practically impossible to research or track it in a meaningful and holistic way.

In 2019 we decided that processing this collection at item level, silhouette by silhouette, would improve the accessibility and visibility of one of the few women artists currently represented in the Museum’s collections, as well as the subjects represented.

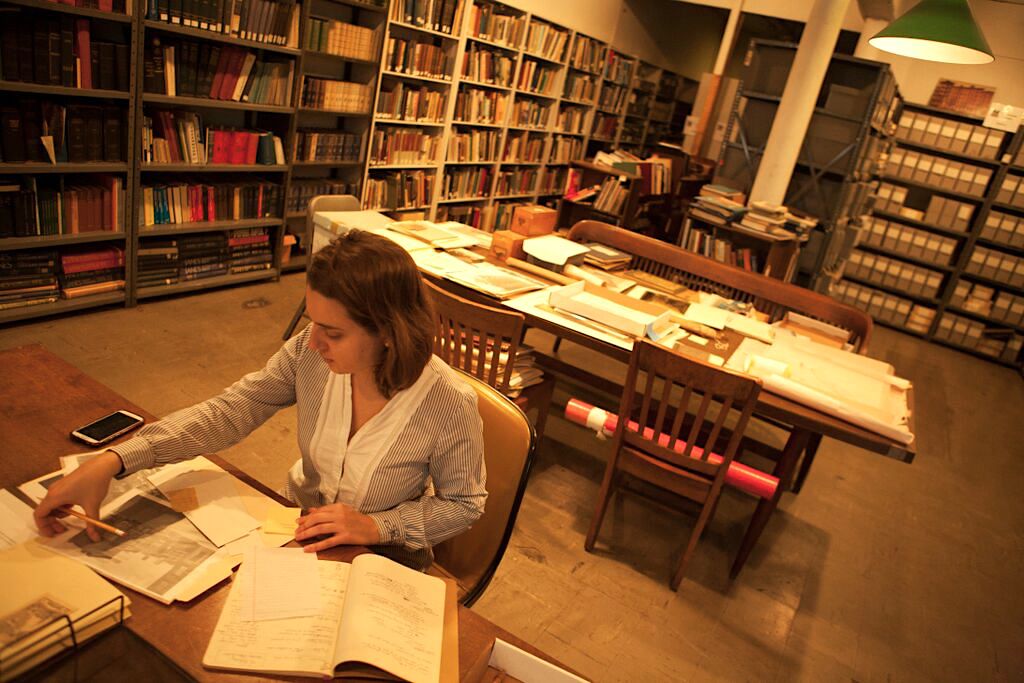

Above left: “Charles Max Foust, Marion, Ind.” 1945. Gift of Elsie Howell, South Street Seaport Museum, 1989.059.0052

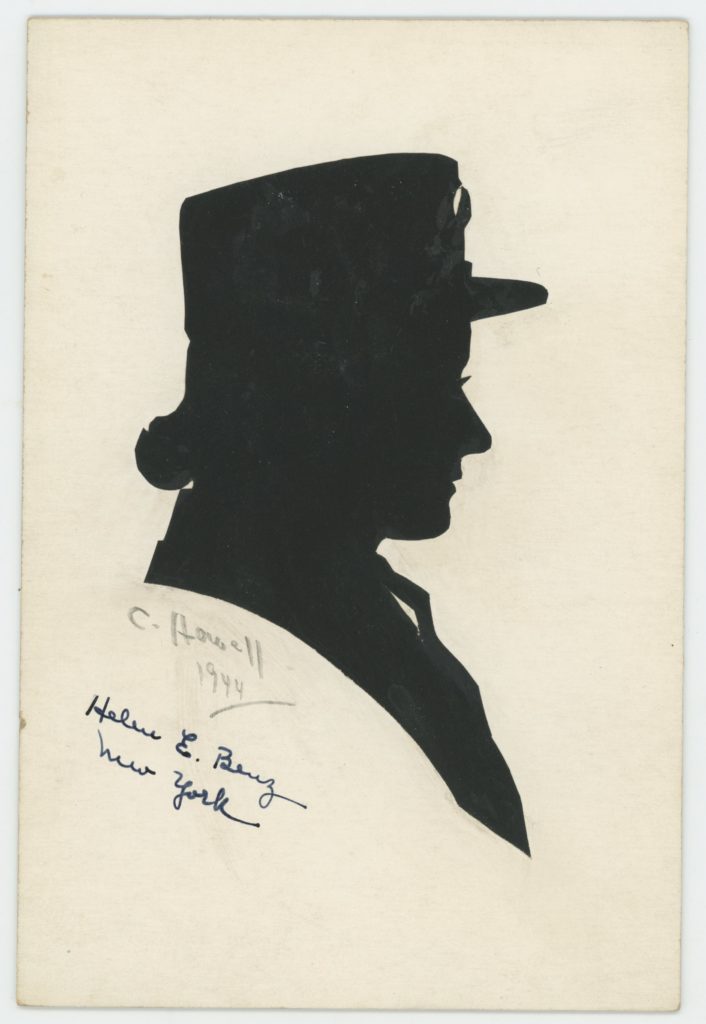

Above center: “Helen Benz, New York” 1944. Gift of Elsie Howell, South Street Seaport Museum, 1989.059.0014

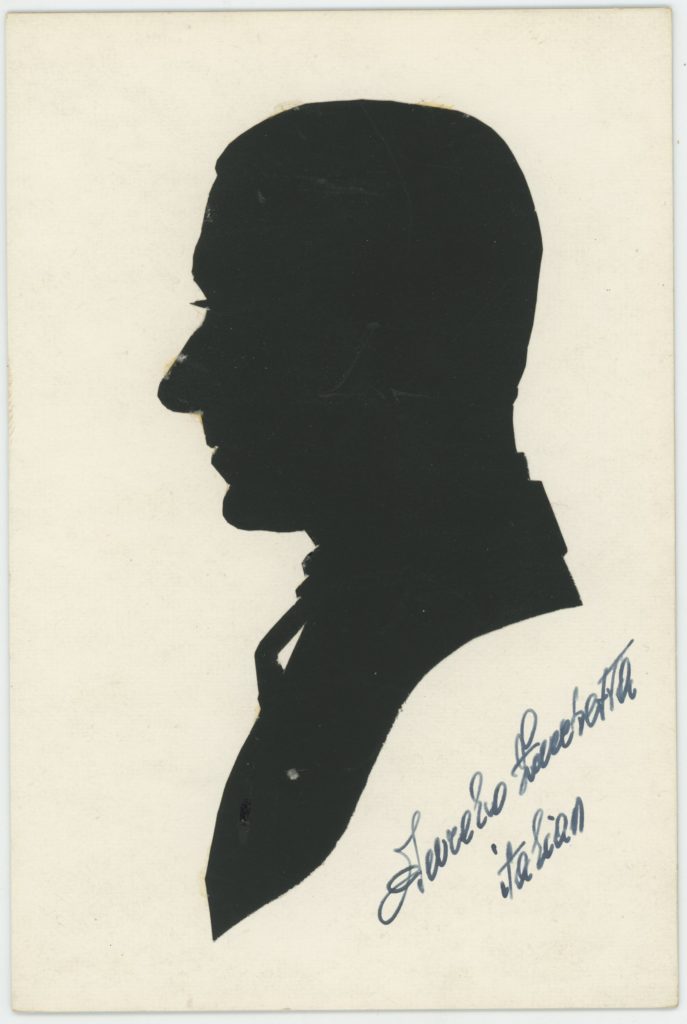

Above right: “Aurelio Gambetta, Italian” ca. 1943-1945. Gift of Elsie Howell, South Street Seaport Museum, 1989.059.0058

Conza Howell

Ms. Conza Howell was a designer and artist, working in a wide-range of mediums including oil and watercolor paint, pastels, and silhouette portraits. She expressed artistic talent from a young age, and moved to New York City sometime before 1932. She attended Columbia University, the National Academy of Fine Arts, the Art Students League, and the Fontainebleau Fine Arts School in France. Around 1935, she was hired as a stylist for the Decorative Fabrics Division of Burlington Mills Corp., New York, specializing in jacquard fabrics.

On September 20, 1943, the United Seamen’s Service (U.S.S.) Program Director, Isabel F. Peterson, invited Ms. Howell to provide some quiet entertainment in the lobby of the Wilshire Hotel on West 58th Street. The hotel at the time was occupied by seamen serving in all theaters of war, and the U.S.S. was anxious to make their short stay in port enjoyable. Peterson asked if Howell would “serve one night a week doing silhouettes of the men so that they could send them home.”

In the years after the war Ms. Howell is noted as a stylist and decorator. She met Howard Moorehead Claney, a well-known radio announcer and artist, at an exhibition of his paintings. They married on March 5, 1949. The couple resided in New York City for many years before retiring to North Carolina in 1970. Ms. Howell Claney died on October 20, 1987.

At the time of Howell’s work, photography had already changed everything. Photography and silhouettes overlapped for just about 10 years until around 1850, at which point the black-and-white profiles that once hung proudly in living rooms began a slow migration into historical society museums and antique markets.

A medium for all

As you can see from the example above, and the many silhouettes now available for free on our Collection Online Portal, silhouettes made sitters appear to be in the same environment, thanks their uniform format and size. For a time, and despite its limitations, the medium offered people—who may otherwise have not been remembered by history—an opportunity to leave a piece of themselves behind in this simple black-and-white art form.

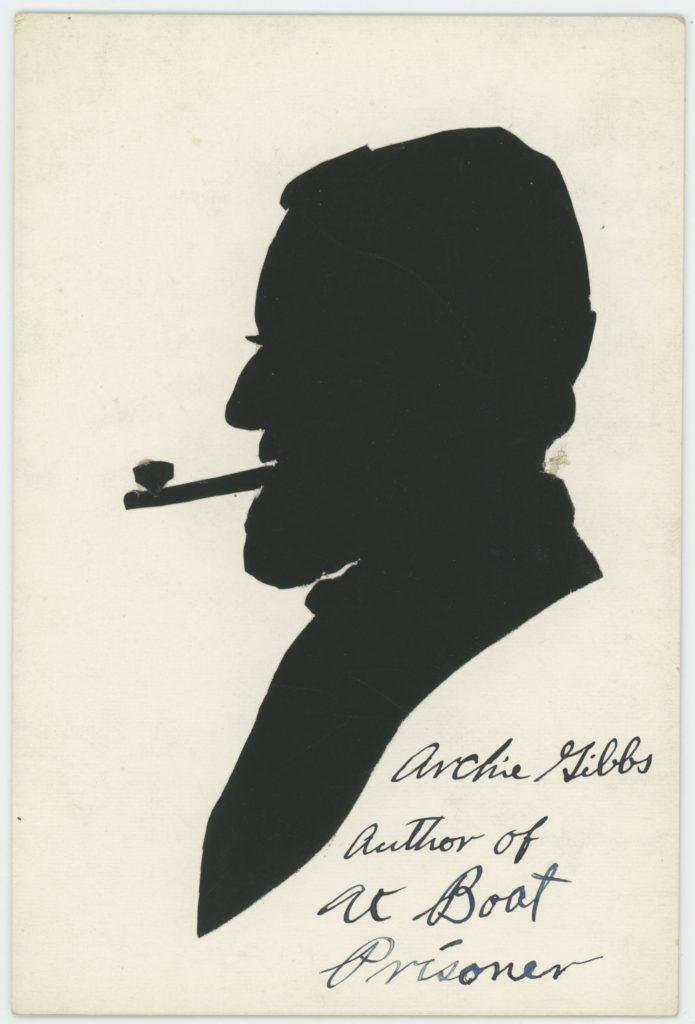

The subjects we’re spotlighting below are thanks to a detailed inventory done by one of our dedicated graduate interns, and include American Women’s Voluntary Services volunteers, US merchant mariners, and the nine-day American war hero Archie Gibbs.

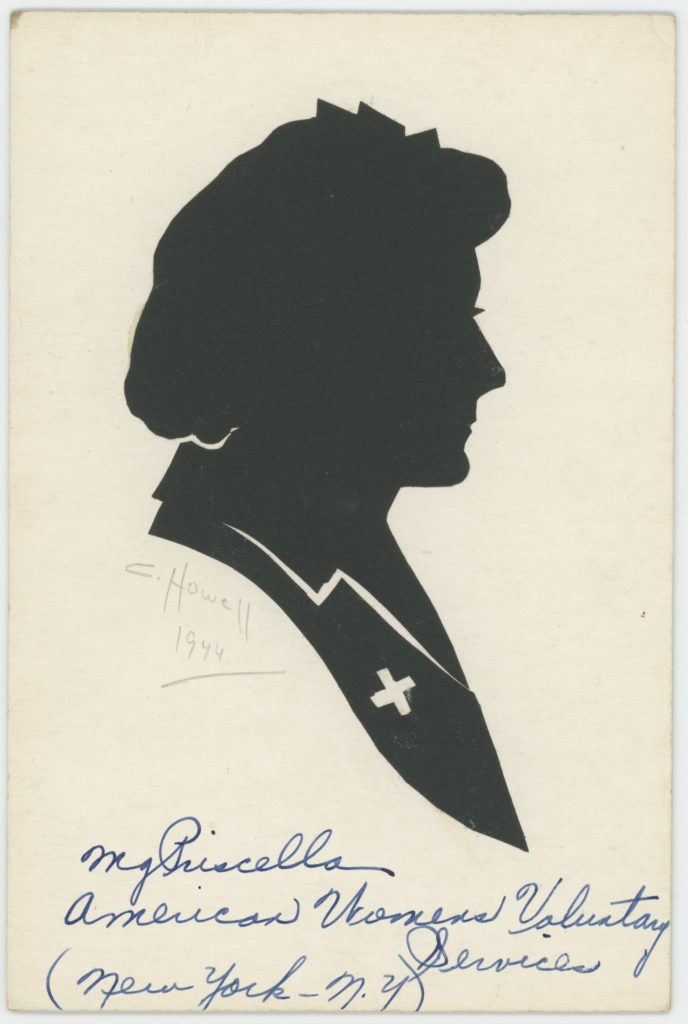

Above left: “Mg. Priscella, American Women Voluntary Service, New York, N.Y.” 1944. Gift of Elsie Howell, South Street Seaport Museum 1989.059.0117

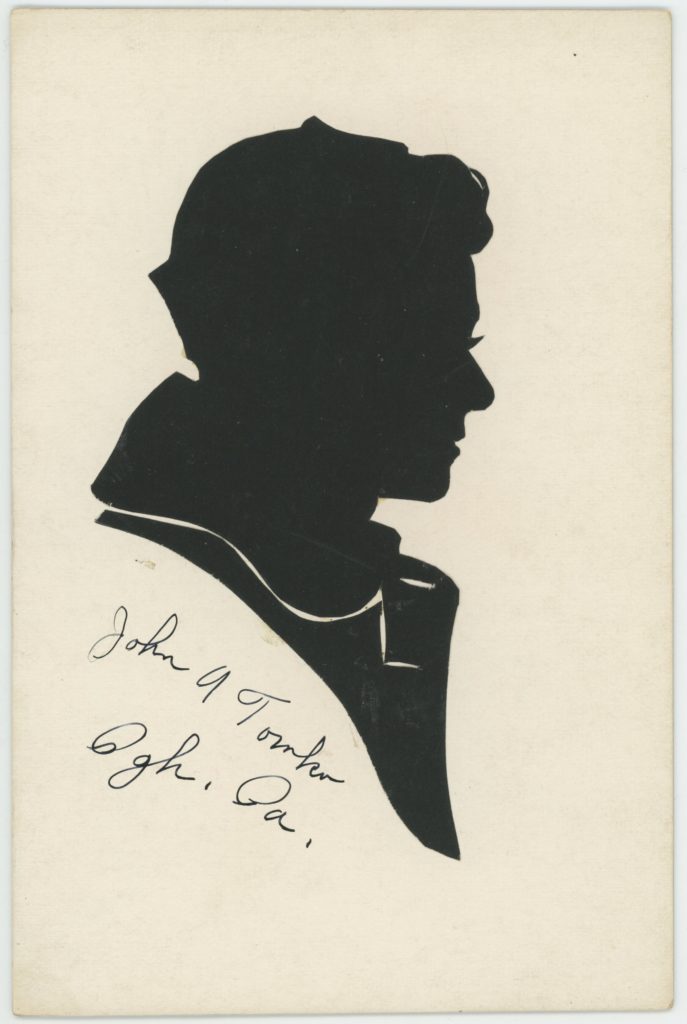

Above right: “John A. Tomko, Pittsburgh, Pa.” ca. 1943-1945. Gift of Elsie Howell, South Street Seaport Museum, 1989.059.0144

The silhouette on the left depicts an emergency services volunteer from the American Women’s Voluntary Services (AWVS). The AWVS was the largest American women’s service organization in the United States during World War II, providing a variety of support services including selling war bonds, staffing emergency kitchens, aircraft fighting fires, and truck driving. In New York City, AWVS trained all-women ambulance crews—even taking over 24-hour ambulance services for some hospitals [5] American Women During World War II: An Encyclopedia, by Doris Weatherford, p. 22..

The silhouette on the right depicts John A. Tomko of Pittsburgh, PA, a merchant mariner that fought during World War II as part of the US military navy forces manned by civilian volunteers. The Merchant Marine was responsible for supporting the US war effort, carrying fuel, ammunition, and other supplies to Navy vessels and foreign shores—often while under attack by enemy ships. The Merchant Marine suffered a higher casualty rate than any branch of the military, with thousands dying in combat, but since they were not military personnel, they were not offered veterans benefits after the war. It wouldn’t be until 1988 that certain World War II merchant mariners were eligible for veterans benefits.

Mr. Archie Gibbs was born in 1906 in Cincinnati, Ohio, and he became well-known for his account of his four-day imprisonment on a German U-boat.

When the United States entered World War II, Gibbs shipped out on convoy duty. He was lucky for a time, delivering supplies on untouched ships. But on June 15, 1942, during a fateful voyage aboard the un-escorted American steamship Scottsburg, a German U-boat attacked and sunk the ship. Gibbs and 45 other survivors were rescued by the American steamship Kahuku, but only a day later, the Kahuku was torpedoed too.

Many of the men aboard were put on rafts by the German sailors, but Gibbs was taken as a prisoner on the submarine. After four days, the Germans pushed him overboard and allowed him to swim to safety aboard a passing Venezuelan ship. When he returned to the States, he was greeted with fanfare: a feature in Life magazine, a photo-op with Eleanor Roosevelt, and a medal from the Maritime Union.

“Archie Gibbs, author of U Boat Prisoner” ca. 1943. Gift of Elsie Howell, South Street Seaport Museum 1989.059.0061

In more recent years this once popular art form is having a contemporary revival. If you are interested in seeing a renaissance of the medium, check out the work of contemporary artists, such as Ana Mendieta (1948-1985), who imprinted her body in various natural environments as part of her “Silueta” series (1973–77), or Kara Walker (born 1969), who is known for creating black-and-white silhouette works that invoke themes of African American racial identity, often including scenes of slavery, and conflict or violence. In a 2007 interview with The New Yorker Walker noted that she “had a catharsis looking at early American varieties of silhouette cuttings,” finding themes that evolved into her own subversion of the medium, which shows the stark realities of racial stereotypes.

Additional reading and sources

The Origins of Silhouettes, by Theodore Lynch Fitz Simons, published in Arts & Decoration (1910-1918), vol. 4, no. 2, 1913, pp. 59–61.

Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic, by Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, published in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 149, No. 1 (Mar., 2005), pp. 22-39.

An Outline of Over 200 Years of Silhouettes, by Claire Voon, published in Hyperallergic on August 14, 2018.

“Done Without Hands”: Meet Martha Ann Honeywell, the Silhouette Artist Who Captivated 19th-Century America, by Kerrie Mitchell, published in New-York Historical Society’s Behind the Scenes Blog on January 14, 2020.

How a Silhouette Artist Traces the Past and Brings History to Life, by Cheyney McKnight, published in New-York Historical Society’s History Detective Blog on January 20, 2020.

References

| ↑1 | Britannica Definition |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Once the Slave of an American Painter, Moses Williams Forged His Own Artistic Career, by Karen Chernick, on Artsy, February 19, 2018. |

| ↑3 | Hans Christian Andersen’s lesser-known talent: paper cuttings, published on DW.com |

| ↑4 | Martha Ann Honeywell: Art, Performance, and Disability in the Early Republic, by Laurel Daen, published in Journal of the Early Republic, University of Pennsylvania Press, Volume 37, Number 2, Summer 2017, pp. 225-250. |

| ↑5 | American Women During World War II: An Encyclopedia, by Doris Weatherford, p. 22. |