Spotlight on Museum Archives Program Volunteers Helping with Transcription

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Elena Abou Mrad, Archives and Special Collections Specialist

and Nick Lockyer, Volunteer Program Manager

November 14, 2024

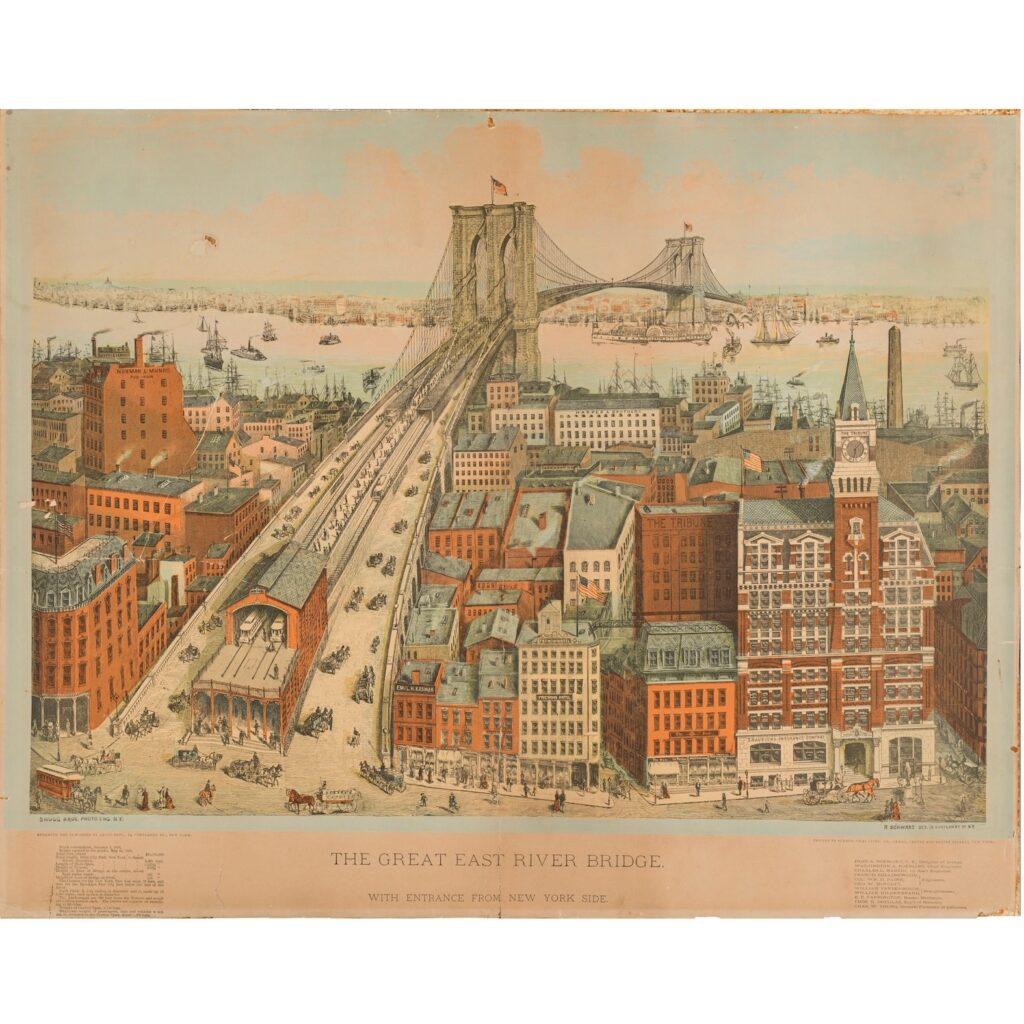

In the late 1960s, a group of passionate New Yorkers lobbied the city to set aside a collection of city blocks in the South Street Seaport as an area worthy of care, attention, and preservation. This group of people became the first volunteers of the South Street Seaport Museum, and laid the foundation for the work the Museum does today in sharing the incredible story of the rise of the port of New York.

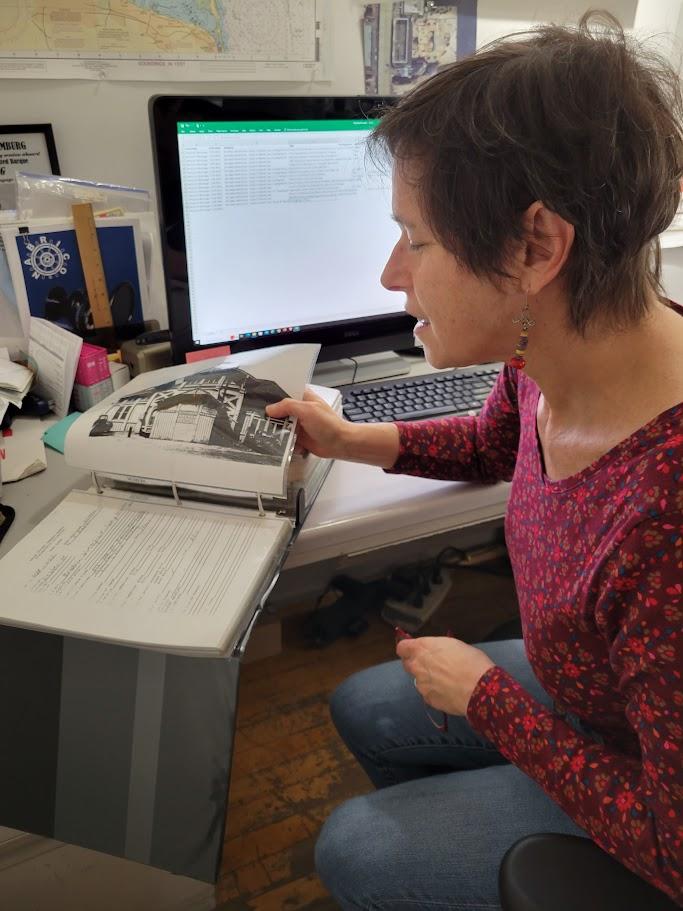

Today, volunteers are most often seen working on the waterfront at Pier 16, and they also support every aspect of the Seaport Museum. Since the Summer of 2023, the Museum has welcomed over 50 new and returning volunteers who have collectively donated over 1,000 hours of their time to help digitize and transcribe the Museum’s Reference Photo Archive—consisting of over 10,000 records! Volunteers have also assisted with cataloging and indexing the Museum’s “South Street Reporter” and “Seaport” magazine publications. This Fall, they are working on transcribing late-18th century to mid-20th century letters, manuscripts, and other handwritten documents from the Museum’s Archives and Special Collections into digital formats.

This blog will explore the latest transcription project as a collaboration between Elena Abou Mrad, Archives and Special Collections Specialist, and Nick Lockyer, Volunteer Program Manager.

Elena here. In my first six months working at South Street Seaport Museum, I’ve often answered the same question from friends and family: “So, what are you archiving at the Seaport Museum?” The Cliffs Notes version of my answer is that the Museum’s collections include three-dimensional objects (fine art, decorative arts, and historical artifacts) and two-dimensional materials, and those “flat” objects are the archival materials. This division is not perfect, as there are “flat” works of art such as drawings and watercolors, lithographs and prints, and fine art photographs. However, I find that the distinction between 3D and 2D helps people visualize that a ship model and a box of letters are different objects, which require a different kind of care[1]See our “About the Collections” page on the South Street Seaport Museum website for more details.

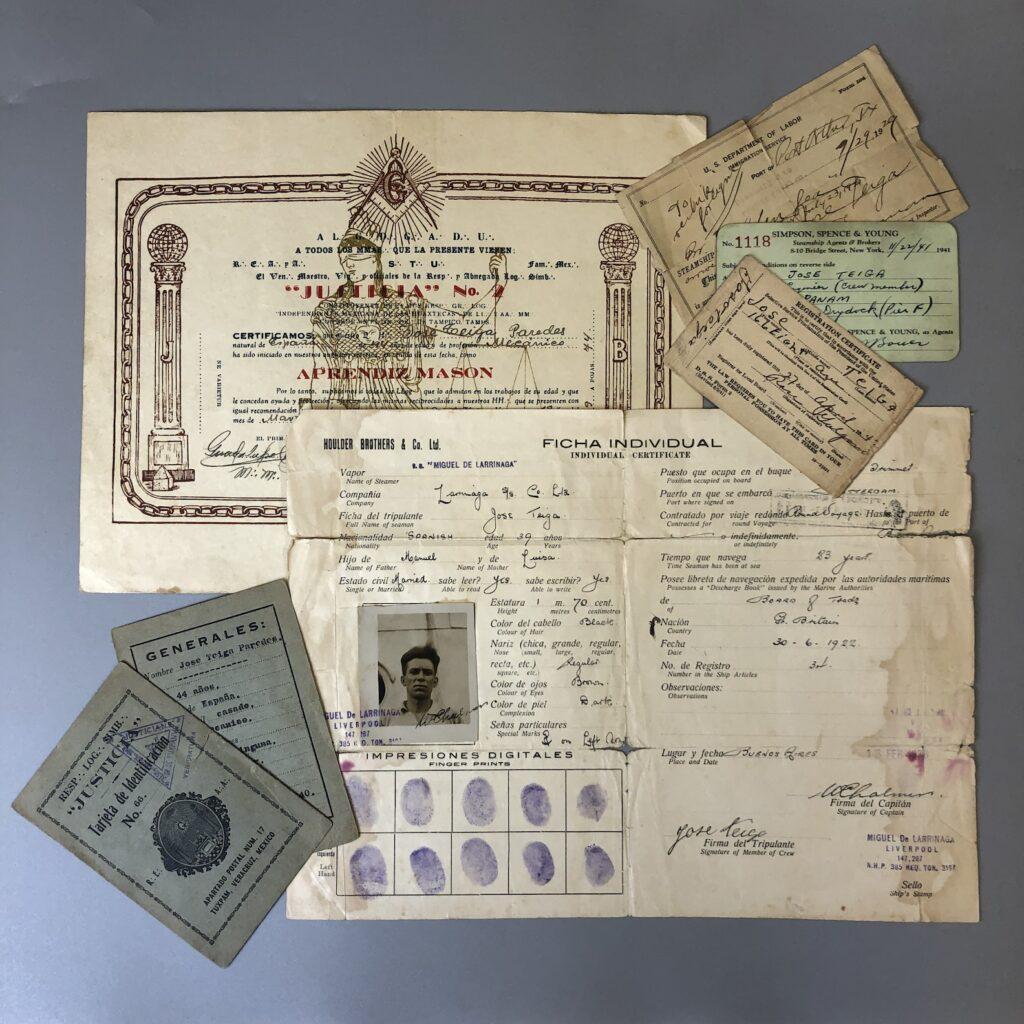

Top Left: [A group of documents from the José Teiga Papers], 1929-1942. Gift of Louise Agnes Teiga, 2003.016

Top Right: “The Great East River Bridge with Entrance from New York Side”, ca. 1883. Gift of William F. Weigel, 1983.102

Bottom Left: “Simon Douglas’s Blacksmith Tongs”, 19th century. Gift of James R. Crane, Sr., 1974.037

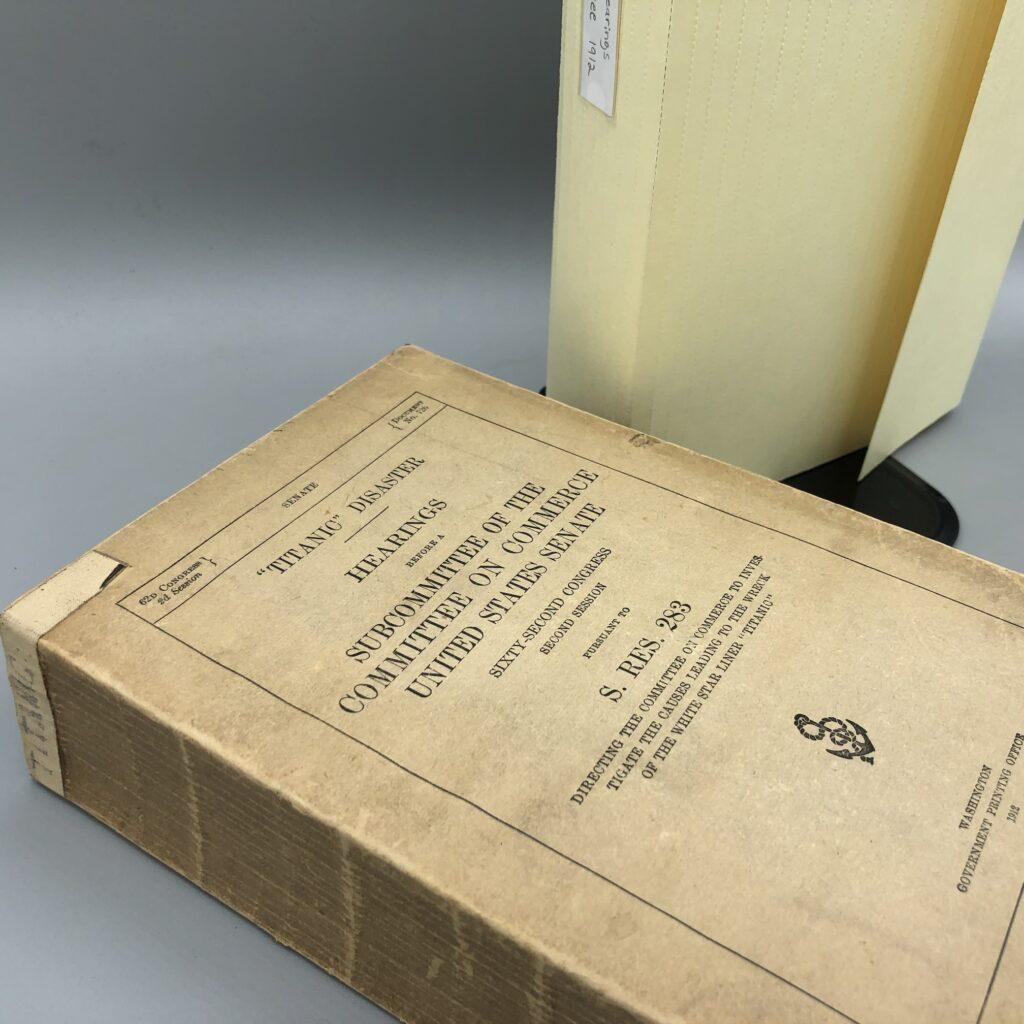

Bottom Right: “Titanic Disaster: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce United States Senate”, 1912. Rare Books Collection

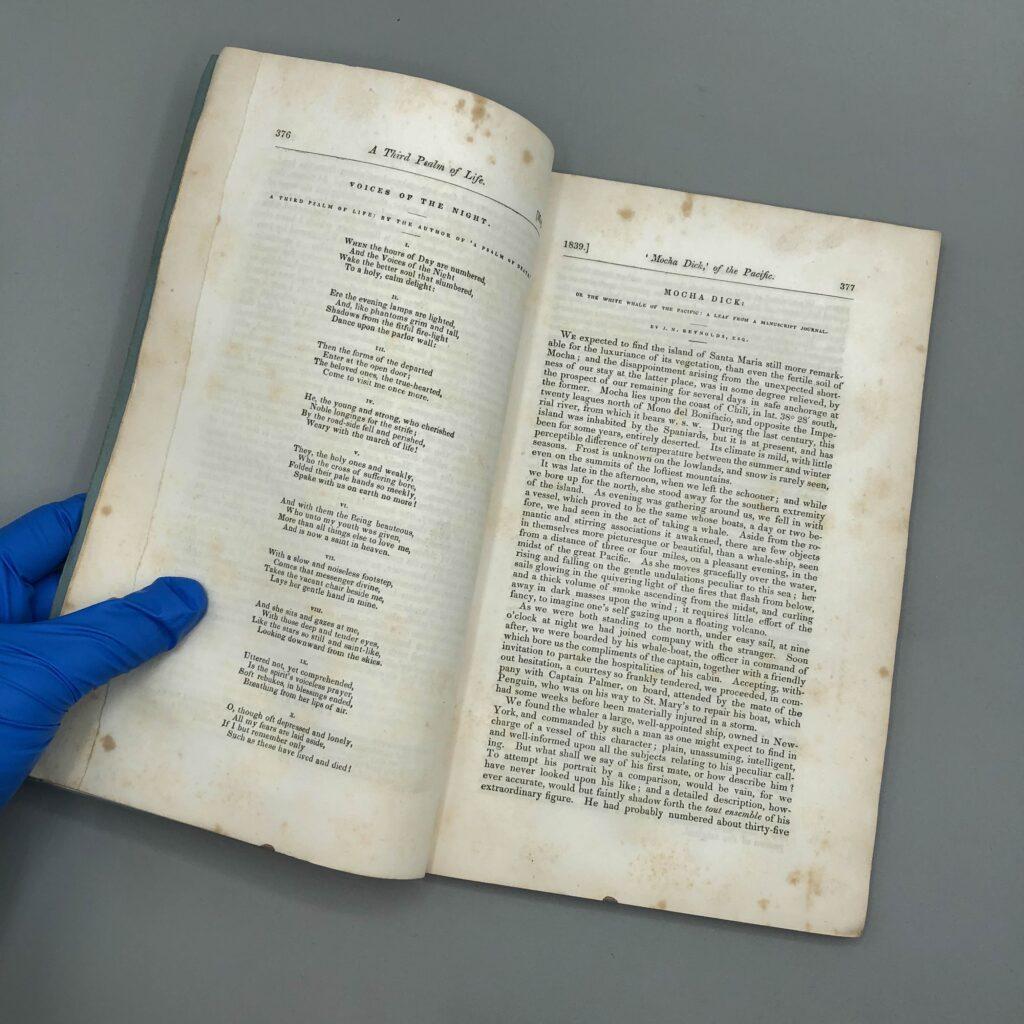

But what are the flat objects that make up the archives? The main kind of archival materials that I interact with are paper-based objects: manuscripts, letters, receipts, official documents, newspaper clippings, and ephemera such as trade cards, menus, tickets, postcards, and much more. I also work to preserve the core of the Photo Archive, which includes photographs and negatives in various formats documenting New York, maritime subjects and the history of the Museum, from 1870s stereographic cards, to 1980s slides and negatives depicting waterfront operations in New York Harbor, and the establishment of the South Street Seaport Historic District. In addition, I organize and preserve the Rare Book Collection, which contains approximately 1,500 books that were mostly published before 1900. These unique volumes cover a wide range of topics, including technical subjects such as ship construction and maritime navigation, and more general maritime heritage subjects within art history and literature. There is even an edition of J. N. Reynolds’ “Mocha Dick, or the White Whale of the Pacific. A leaf from a manuscript journal” (1839); guess which epic American novel this manuscript inspired?

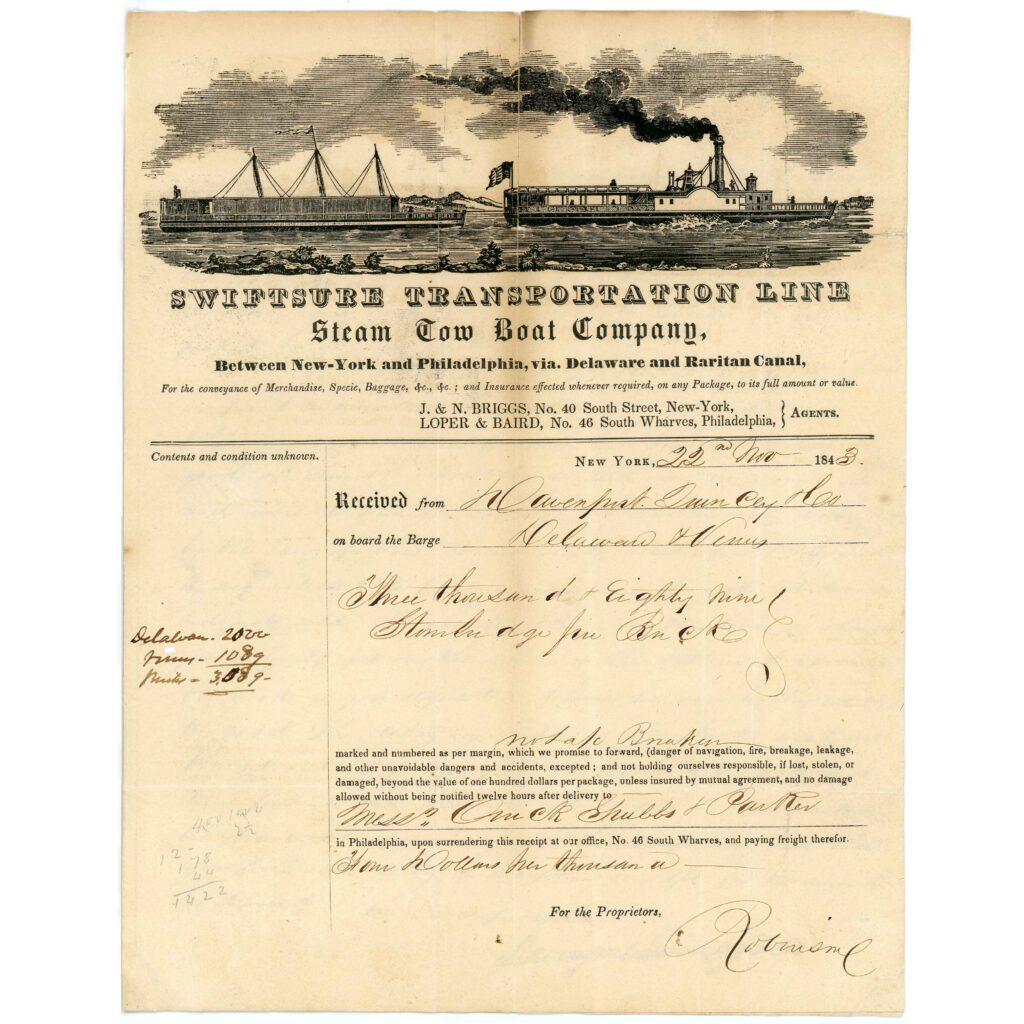

Left: [Receipt from Swiftsure Transportation Line], November 22, 1843. Gift of David L. Jarrett, 1980.162

Center: [Sailors dancing on Front Street during Operation Sail ’76 festivities], July 1976. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive.

Right: “Mocha Dick, or the White Whale of the Pacific (from a manuscript journal),” 1839. Rare Book Collection

When inventorying and cataloging historical records, any archivist is faced with a difficult choice: as much as we’d like to do a deep dive into every detail of every document, this would take a lot of time and effort making the work unsustainable. Instead, we decide to gather the most essential information: in the case of a letter, for example, the cataloger records the sender, receiver, date, and general topic of the message. But what about the rest of the text? That’s where the Seaport Museum volunteers participating in the Museum Archives Program come in to assist!

Nick here. When I first stepped into my role as Volunteer Program Manager for the Seaport Museum, it felt like a perfect blend of my personal interests with woodworking and maritime history, and my professional skills as a museum educator and organizer. I have been working in museums for eighteen years and in many different roles. I started out as a volunteer myself at the Frick Pittsburgh; when I completed my undergraduate studies, I returned to my volunteer roots there, researching and writing articles and assisting with education programs and special events. Stepping into my current position leading the Volunteer Program for the Seaport Museum felt like the completion of a circle in many ways.

For decades, Seaport Museum volunteers have helped sail the operational vessels as crew in the Sail Training Program and worked shore-side in the Ship Restoration Program to keep the fleet of historic vessels maintained and in good working order. It’s a truly unique experience that you would be hard-pressed to find elsewhere in the city at the same scale, but it does come with some drawbacks.

Left: Pioneer crew scrubbing the deck, June 1980. South Street Seaport Museum, Slide Collection.

Right: Waterfront volunteers carrying Wavertree‘s awning down belowdecks for storage, October 28, 2023. South Street Seaport Museum

The waterfront volunteer roles are often physically demanding and usually susceptible to weather, since much of the work is performed outdoors or in spaces that aren’t climate-controlled. All this to say, there was a desire and need for a volunteer opportunity that was more weather-stable and could engage volunteers with additional types of work such as archiving, education, and docent work.

I began speaking with the Collections and Exhibition team to see if volunteers could support their work. We landed on a few ideas that formed the foundation of what would become the Museum Archives Program.

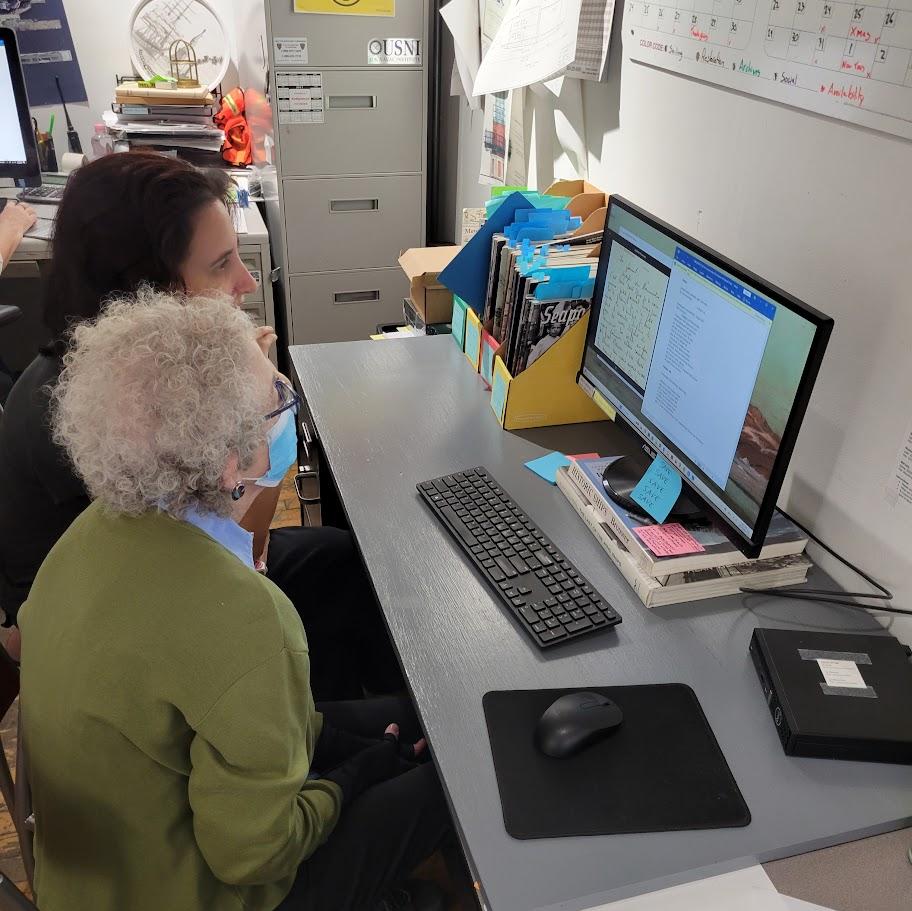

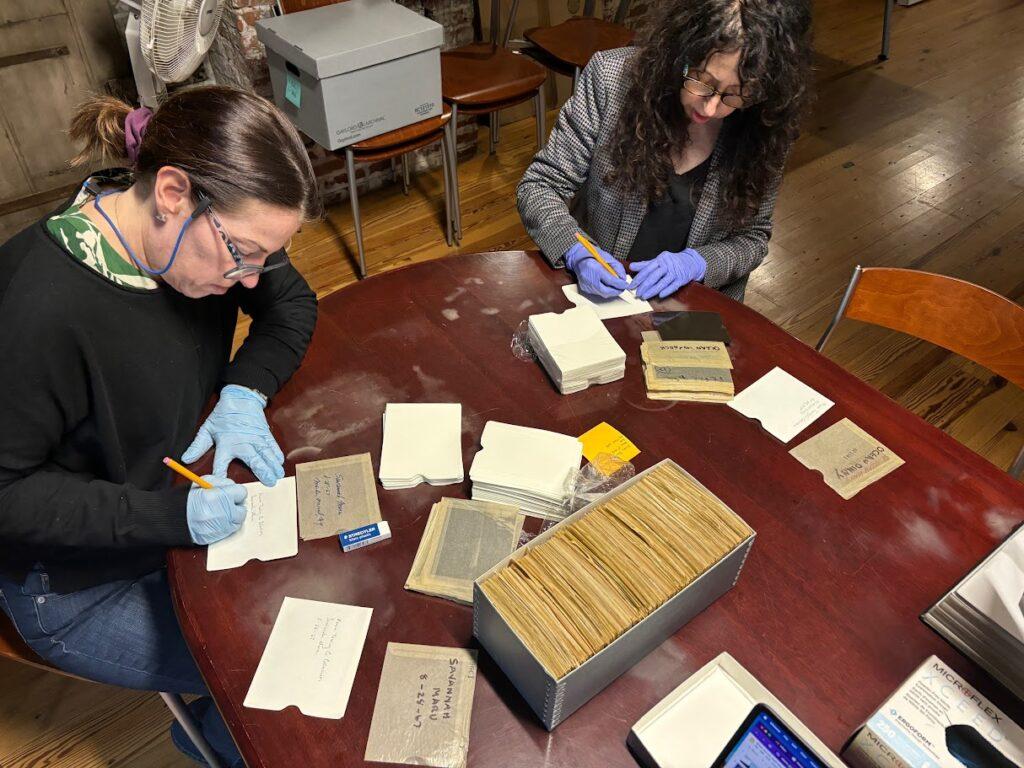

We are currently working on our most ambitious project yet. Volunteers are reading and transcribing historic letters, manuscripts, and records from the archives, so they can be made more accessible internally to staff and externally to researchers.

There are several reasons that this is the perfect project for the Museum Archives Program volunteers. First of all, this group is passionate about history, and, for many people, the most exciting thing about history is experiencing and interacting with historical documents. The second factor is that many of the records from the Archival Collections have already been digitized: this way, volunteers can read the documents from their own work stations in the office, without needing access to collections storage or specific training on how to handle original documents—which is the realm of specially-trained archivists and their trainees. Last but not least, we are constantly thinking about making our collections more accessible, and with digital scans volunteers can zoom in, rotate the images, and adjust the brightness of the screen to better discern the text.

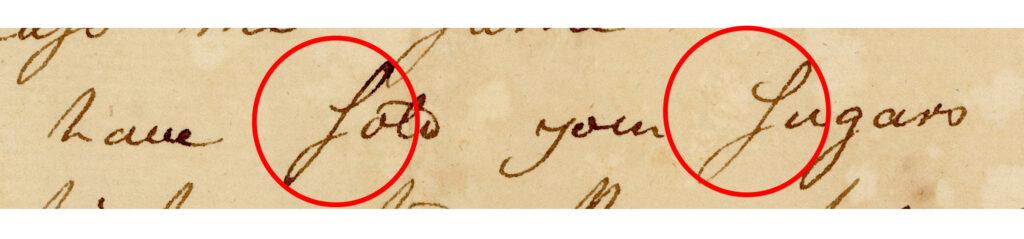

The Collections team created a list of potential documents to transcribe on the Museum’s collections management database[2]”A collection management database is a software system designed to catalogue and manage collection items, plan and manage exhibitions and loans, organize conservation documentation, and manage … Continue reading—and this list is steadily continuing to grow. Together, we created a system to assign, track, and review the volunteers’ individual projects, as well as an instruction manual containing tips and tricks for transcribing historical documents. For example, did you know that the lowercase “s” can look like an “f” in old handwritten text? In this detail from a letter dated December 5, 1800, you can see the so-called “Long S” at the beginning of the words “sold” and “sugars.” The “Long S” was commonly used in letter writing in the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century[3]Handwritten Historical Documents Transcription Tips, UHCL Archives and Special Collections, University of Houston Clear Lake..

Detail from [Letter from James Bogert to John D’ Wolf], December 5, 1800. Gift of William R. Bogert, 1980.089.0003.c

Once a volunteer completes transcribing a document, they submit it for review. When the edits have been approved, a PDF of the transcription is ready to be added to the database. While working on each document, volunteers are encouraged to collect keywords, list the abbreviations and misspelled words in the original text, and describe the tricky parts they encountered while working. All of these notes are really helpful because we use this information to update the database entry for each object. This way, the historical documents become more accessible and searchable.

Transcription Opportunities and Rewards

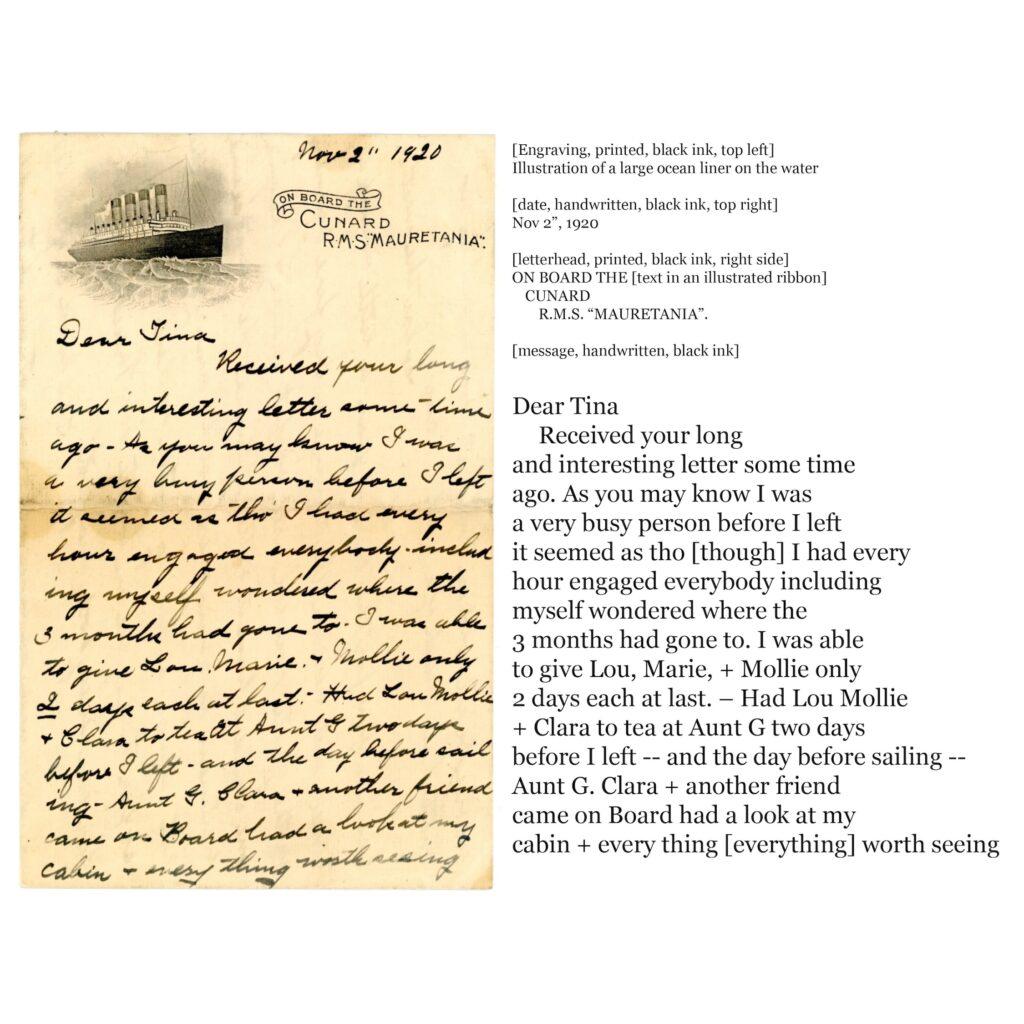

Volunteer Tiffany L. had this to say about the transcription project: “To get a peek into the life aboard the Mauretania of this girl who wanted to talk about what she wore to a wedding, about what her dad said about a family friend, about the latest happenings with other girls on the ship—they’re some of the same things I would talk to my friends about. I was so delighted to discover that even though we’re separated by over 100 years, some things don’t change.” Though only the first part of the RMS Mauretania letter is present in the archival collections, this made Tiffany even more curious about the gossip that it probably contained: “The missing page made me want to know more than ever what Helen’s dating history was like!”

RMS Mauretania Letter, November 2, 1920. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation, 2006.029.0749

Laura M.S., another volunteer, has transcribed eight historical documents since the project launched in early September:

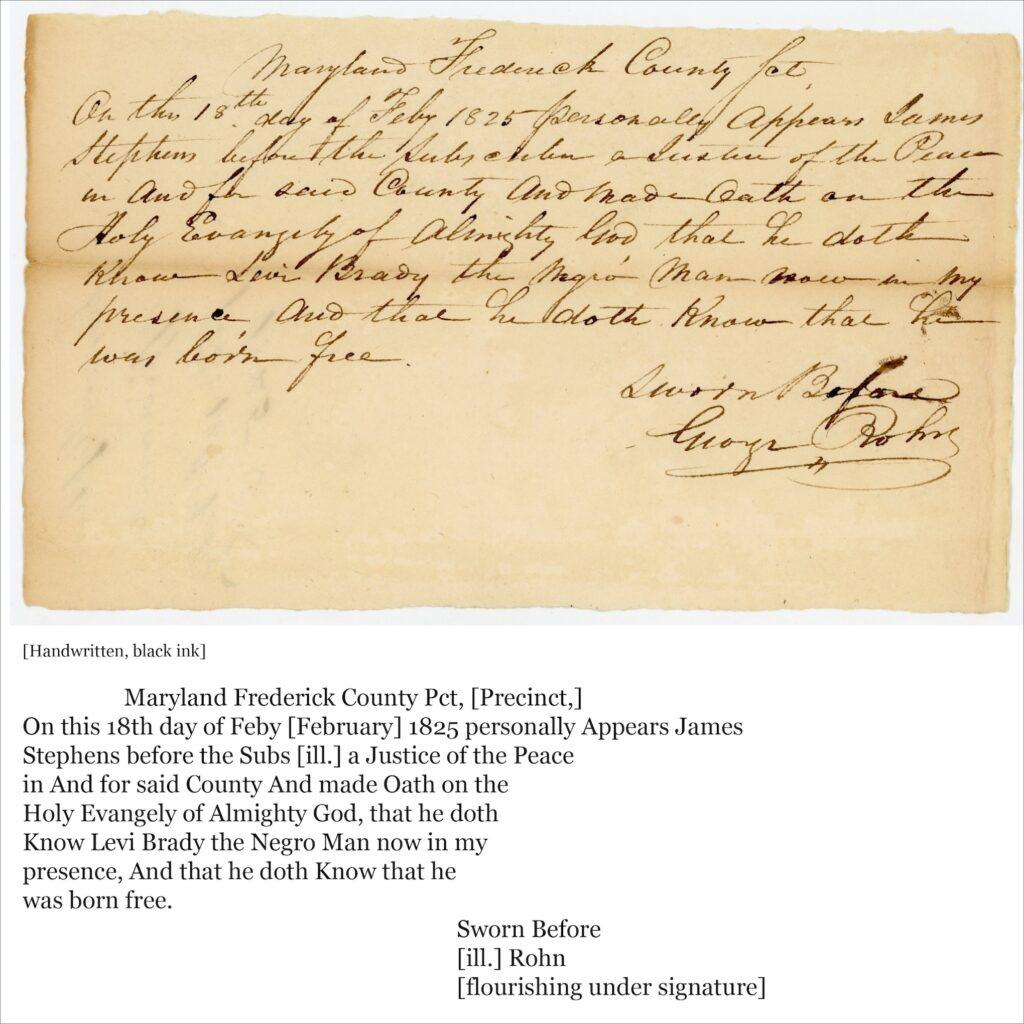

“The standout item for me is 1997.013.0005, and I held my breath reading it, realizing its social weight and the importance of it to its bearer in his lifetime. Written in Frederick County, Maryland in 1825, it states that a free black man named Levi Brady, was born free and ‘that he doth know that he was born free’ as sworn by James Stephens before the justice of the peace. This small piece of paper written in a steady and purposeful script preserved in the collection is evidence of the fragility of freedom.”

[Document testifying that Levi Brady was born free], February 18, 1825. Museum Purchase, 1997.013.0005

“Transcription has its challenges and sometimes single words or short phrases can be difficult or impossible to decipher, but it is an intriguing process. I feel a responsibility to get it right and to provide the utmost accuracy to all items I am allowed to work with, so that these items will be true representations of the original documents. While I obsess over scripts and spelling, relish looking at the incredible printed typefaces on receipts and business letterhead, and note the speed of the writing quality or the flourishes in letterform or description as provided by the writer, the information these hold can live on and be useful to researchers in a digital context even as the physical objects degrade over time. The satisfaction of feeling that I have provided all of the description I could for each document is worth all the time and care it takes to do it. It allows me the feeling, literally, of dotting every i and crossing every t because if it mattered to the original writer, then it must matter to me.”

Volunteer Roselyn H. shares her favorite transcription so far:

“Old letters tell us so much about other times and places. I’ve been reading a letter written in 1939 by a young French woman. She and her mother traveled by train to Paris and later boarded the SS Normandie, where he began a journal. The handwriting is beautiful but sometimes difficult to decipher. Fortunately, one of the other volunteers is a native French speaker. I don’t have to translate the letter, but she can help me understand the text and accurately transcribe it.”

She worked on this project with volunteer Pauline P. who discovered that the letter was not written by a man like originally thought, but by a young woman. “I don’t have to translate the letter, but she can help me understand the text and accurately transcribe it.”

Archival Accomplishments

Since the project started, the volunteers participating in the Museum Archives Program have transcribed 22 historical documents, with many more in the final stages of review as we publish this blog post. We can measure their success not only in terms of numbers, but in terms of impact—on the archival collections and on the South Street Seaport Museum community as a whole.

While drafting the instructions for volunteers working on the transcription project, we took inspiration from the transcription initiatives at the National Archives and the Library of Congress. That’s when an interesting thought struck us: these are gigantic institutions, with long histories and vast resources—and we were trying to launch a similar project at the South Street Seaport Museum!

One of the goals of the Collections Department is to make historical documents more accessible to the public, and the transcription project has created not only a bridge between the Museum’s collections and the outside world but also fostered a sense of stewardship over the collections in our volunteers. Moreover, volunteers have made it possible to identify the contents of historical documents that tell a bigger story about the Port of New York and its connections to the rest of the world. A great example of this diversity in the collections are the ten letters from James Bogert to John and James D. Wolf, two brothers from a powerful family in Bristol, Rhode Island.[4]The Bristol Historical & Preservation Society holds the D’Wolf Family papers, composed primarily of the papers of John D’Wolf (b. 1760) and secondarily of his brother, Senator James … Continue reading

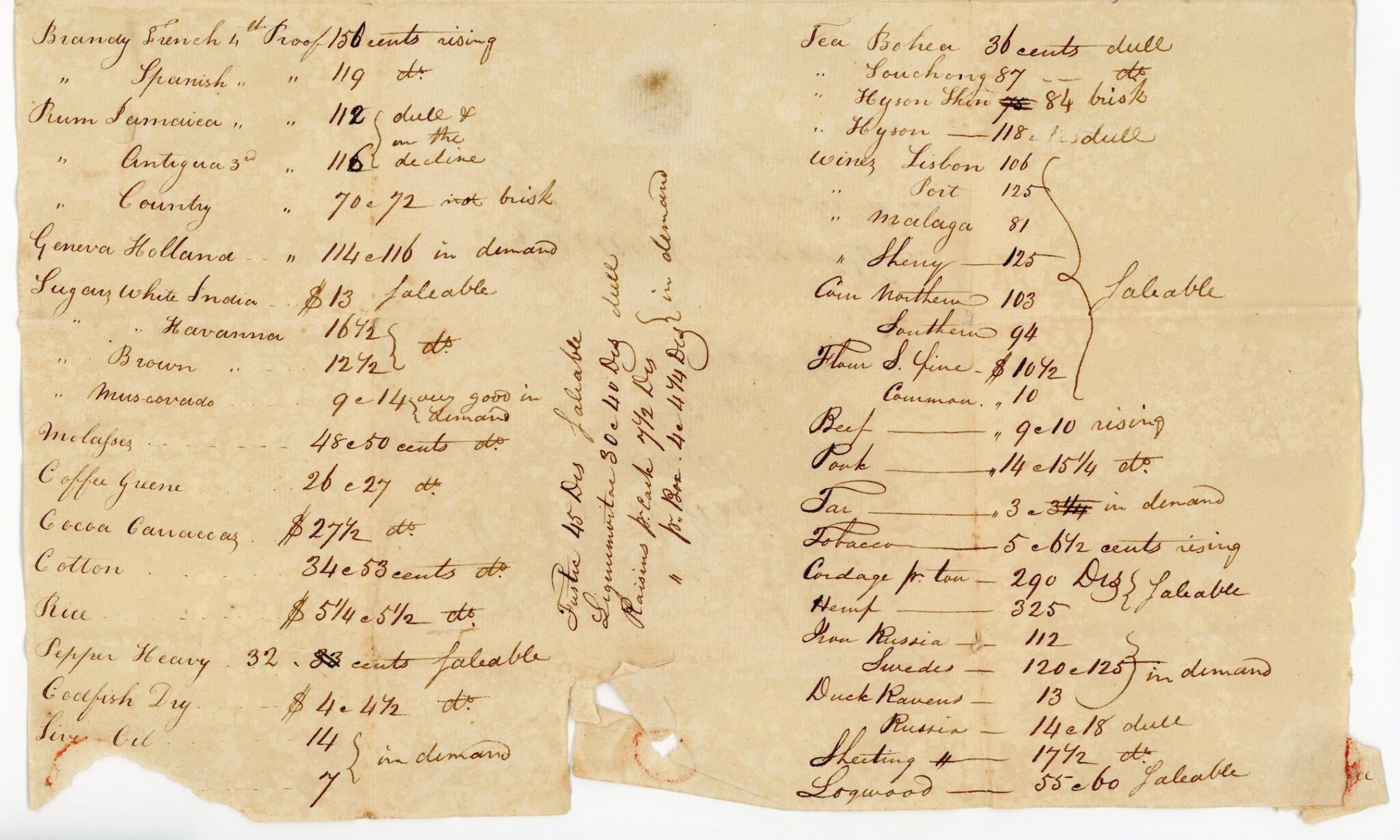

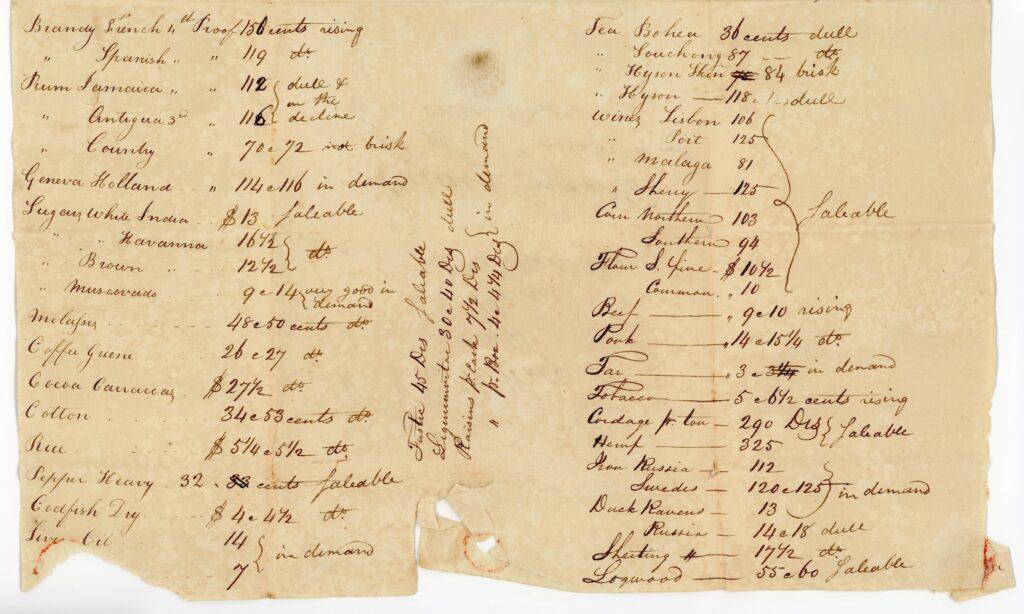

[Letter from James Bogert to John D’ Wolf], December 5, 1800. Gift of William R. Bogert, 1980.089.0003.c

This business correspondence, written between February 1799 and December 1804, documents the variety of goods that were traded through the Port of New York at the time: tea, coffee, cocoa, sugar, spices, tobacco, and cotton, just to name a few. The products listed in these letters provide precious information, not only about what people in New England ate and used in their daily lives, but also about how pervasive the slave trade and colonial exploitation were.[5]The D’Wolf family participated in the slave trade from 1786–1808 although it was illegal under Rhode Island law. D’Wolf Family papers, Bristol Historical & Preservation … Continue reading

An unexpected side effect of the success of the transcription project showed up at this year’s Volunteer Rodeo, which took place aboard the 1885 tall ship Wavertree on October 19, 2024. At this annual celebration, in addition to competing in games that test the skills volunteers often use on the waterfront, like line-tossing, knot-tying, and other nautical games, volunteers could now go head to head in a new challenge: the Transcription Race.

This game had three rounds of increasing difficulty, in which participants were judged based on both their speed and accuracy. Volunteers from the Museum Archives Program, Sail Training Program, and Ship Restoration Program all took part in the game, and even some staff members joined in.

It’s not easy to transcribe a historical document while being timed, but all participants rose to the occasion. It was a real joy to see participants in all three branches of the Volunteer Program come together and interact with the collections and archives of the Seaport Museum in a fun, new way.

Volunteer Victories

Building the transcription project from the ground up has been such an interesting journey.

In the volunteer opportunity description for the Museum Archive Program, when we say no prior experience is needed, we mean it—all of the training is provided when we onboard new volunteers. Someone’s resume has never been a factor in whether someone volunteers here because the point is for people to learn and grow. We seek out people looking for new and engaging experiences, so oftentimes there’s plenty of drive to learn, and it must be met on our end with patience, clarity, and understanding. Some days, volunteer projects can be thrilling, and some days they can be mundane or even a bit tedious. The metadata entry of the Museum Archives Program is the equivalent of painting and sanding of the Ship Restoration Program. It’s repetitive, but it’s also satisfying, and many hands make light work. Then, the next day you’re reading and transcribing gossip-filled letters sent from an ocean liner or you’re building bunks for the crew’s quarters on Wavertree. All the while, it’s our job as supervisors and trainers to convey the importance of each and every one of those projects. We don’t simply sit a volunteer down with a task and instructions; we also help answer, “why are we doing this?” Answering that question thoughtfully enriches the environment of learning for volunteers, and it promotes the kind of caring and stewardship that makes them want to stay and be a part of what we’re doing at the Seaport Museum.

At the end of the day, the goal for all volunteer opportunities is to create a thriving community centered around shared interests and experiences, while teaching people valuable skills, some traditional and some modern. We care about making sure that volunteers feel satisfied with their experiences at the Seaport Museum, and that they feel like they are a part of the Museum team. The volunteers who have participated in the transcription project as part of the Museum Archives Program have become more engaged with the Museum and with each other. The volunteers work together to decipher tricky handwriting and tackle challenges. They talk with each other as they work about the subject matter, laughing at the similarities between themselves and the people who wrote these documents 100 years ago. Along the way, they help Museums staff become better teachers and communicators as they work with us and ask questions.

Additional reading and resources

“Colonial Currency“, by Julie Miller, Library of Congress, May 2020.

“Handwritten Historical Documents Transcription Tips”, UHCL Archives and Special Collections, University of Houston Clear Lake.

“Transcription Tips”, in “Citizen Archivist Dashboard”, National Archives.

“Transcription: Basic Rules“, in “By The People”, Library of Congress.

References

| ↑1 | See our “About the Collections” page on the South Street Seaport Museum website for more details. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”A collection management database is a software system designed to catalogue and manage collection items, plan and manage exhibitions and loans, organize conservation documentation, and manage digital assets. (…) The Seaport Museum’s internal collection management database, Collector Systems, contains nearly all digital records of the Museum’s permanent and working collections of over 28,500 items, along with thousands of associated records of artists, Museum publications, exhibitions and loans history.” Martina Caruso, “Accessible, Available, and Online: Welcome to the Collections Online Portal,” Collections Chronicles, February 25, 2021. |

| ↑3 | Handwritten Historical Documents Transcription Tips, UHCL Archives and Special Collections, University of Houston Clear Lake. |

| ↑4 | The Bristol Historical & Preservation Society holds the D’Wolf Family papers, composed primarily of the papers of John D’Wolf (b. 1760) and secondarily of his brother, Senator James D’Wolf (b. 1764). They were a powerful family with many many enterprises, including the slave trade, the Arkwright Mill in Coventry, and the Bank of Bristol. D’Wolf Family papers, Bristol Historical & Preservation Society. |

| ↑5 | The D’Wolf family participated in the slave trade from 1786–1808 although it was illegal under Rhode Island law. D’Wolf Family papers, Bristol Historical & Preservation Society. |