The many names of 213-215 Water Street

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Manager of Collections Information and Research Services

August 18, 2022

The South Street Seaport Museum’s building at 213-215 Water Street has been under renovation for the past two years. When the construction is completed, the Museum will have accessible exhibition galleries and flexible spaces like we haven’t had since the destructive storm surge of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. As a staff member who joined the Museum in 2015, I’ve been beyond excited to see this new opportunity to share our collections and programs with the public take shape.

Though I can name my emotion towards the 213-215 Water Street project (thrilled), this blog post is about the confusion caused by the many names given to 213-215 Water over the years, and how I found that the nickname given to the building over 50 years ago was ever-so-slightly misleading. In short, this post is about how an 1868 building is getting a “new” name in 2022—and how that name came about.

What’s in a name?

Names of people, places, and things change over time for a variety of reasons. One of my favorite examples is the Museum’s 1885 tall ship Wavertree which was originally named Southgate. The name Wavertree was given in 1888 when the ship was purchased by R.W. Leyland, who would own the vessel for the rest of her sailing career. This is why the ship’s bell has the name “Southgate” inscribed instead of “Wavertree.”

Southgate’s Ship Bell, 1886. Bronze Gift of the Maritime Museum of Gothenburg, Sweden 1976.032

Buildings can also have many names; this can happen as the occupants and use of the building evolves, or when a building is renamed in someone’s honor. A great example is Castle Clinton (built 1808-1811) in Battery Park which has gone from harbor fortification to concert hall to immigration station to aquarium to National Monument. [If you want to follow this building’s many names read more with Carley’s fantastic blog.]

As you can imagine, the changing ways in which a structure is referred to can be a challenge for researchers. If a researcher is looking for information related to a building, but isn’t aware of a name used in various written records, important aspects of the building’s history can be missed. Since building names are often unofficial, it is usually easier to search for more permanent designations like street number or city block and lot numbers (though these can also be subject to change).

“Official” building names are often shortened and adapted by different communities as well. Though the New York Public Library in Bryant Park may be most properly called the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, it is also referred to as the Main Branch, the 42nd Street Library, or simply the Schwarzman Building. A group of librarians at the NYPL could probably refer to the building as just “Schwarzman” when speaking to one another. These variations can be an extra complication.

I know that I have unthinkingly given directions using shortened names for buildings in the neighborhood—telling a friend that they can find “Low” around the corner from “the Row.” The use of colloquial names is not only an issue for researchers, as it can also be an issue for visitors trying to move around the Museum.

Thankfully, my role in the Collections Department does not include planning way-finding or visitor flow between the different buildings and ships the Museum operates around the South Street Seaport Historic District.

However, when the name Thompson Warehouse for 213-215 Water Street came into question, I was happy to take a deep dive into our collections and archive to research the building’s history. I found that 213-215 Water had gone by many names since the Museum was founded in 1967, and that the name Thompson was a relatively recent one used by the institution.

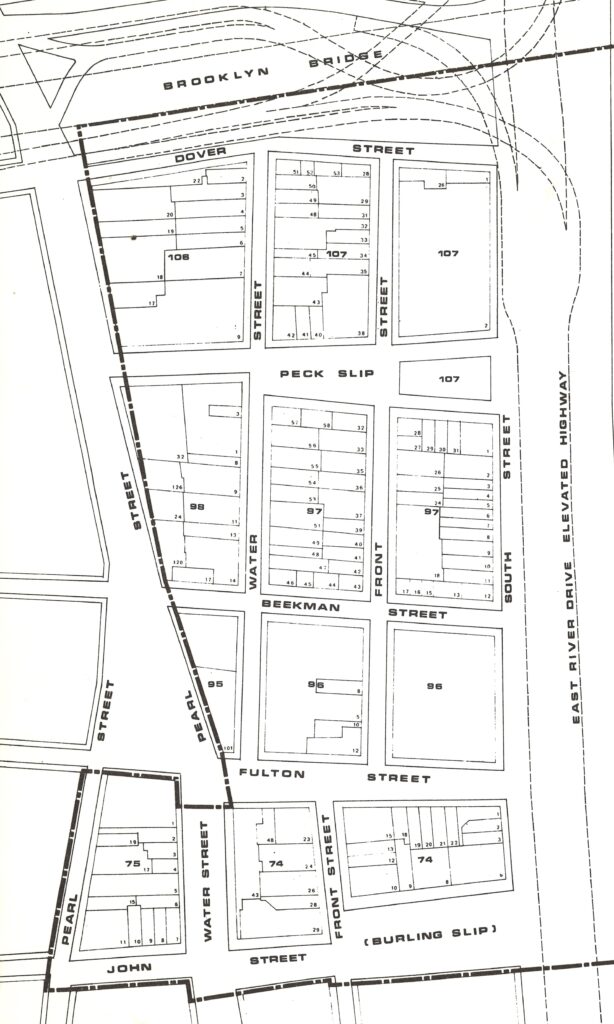

City of New York Housing and Development Administration. “Project Boundary Map”, revised May 10, 1969, from Brooklyn Bridge Southeast Urban Renewal Plan. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

The Seaport Gallery

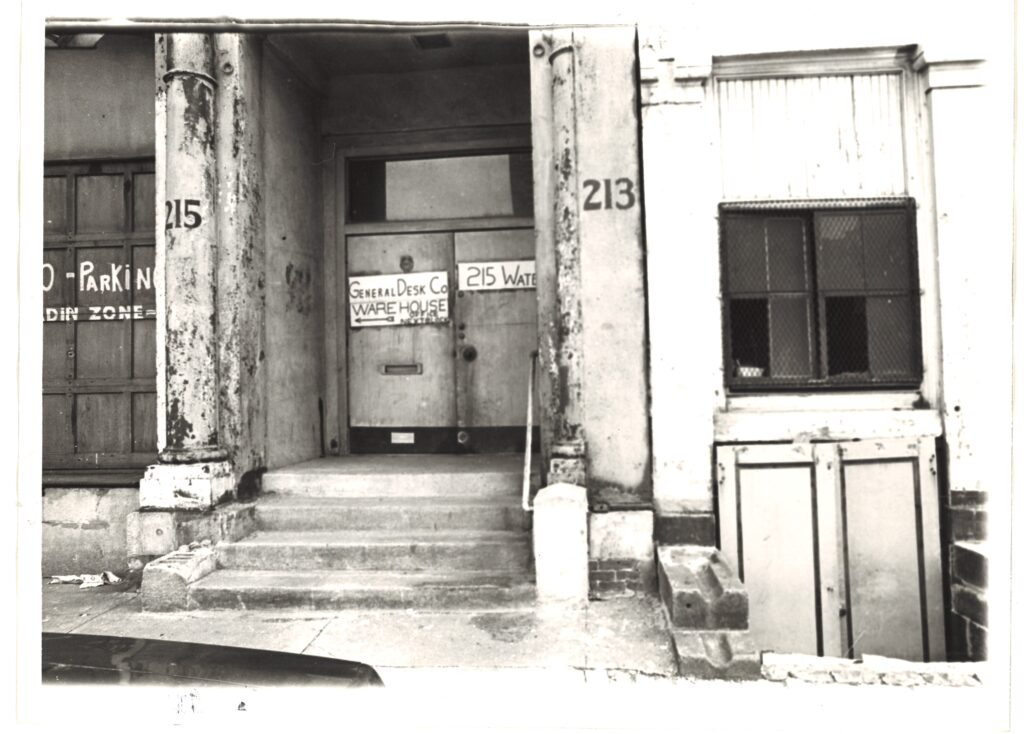

Left: John Stubbs, photographer. 213 Water Street – Door Detail, February 14, 1973. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

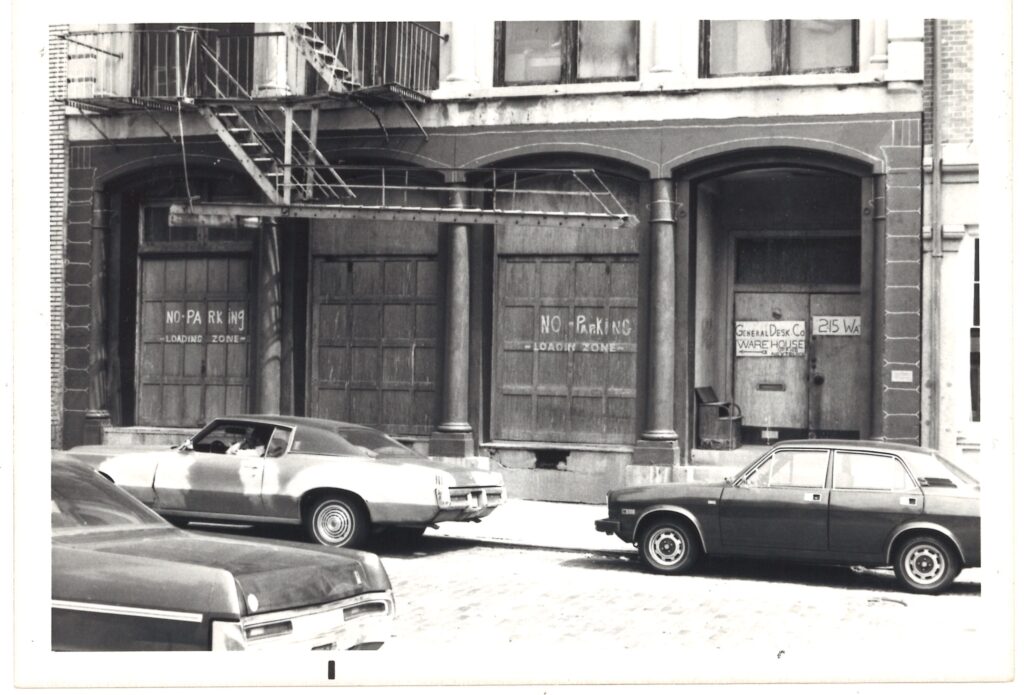

Right: Norman Brouwer, photographer. 213 Water Street, ca. 1973. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

The first name given to 213-215 Water Street during the Museum’s fledging years was actually assigned by the existing tenant: The General Desk Co. These photographs from the 1970s show the ground floor facade of the building, with the door painted “General Desk Co. Warehouse -> Office next block” These photographs, aside from showing the gritty commercial character that the neighborhood was once known for, depict the building before it was renovated for Museum use. These photos also show how the mid-19th century building had been adapted and changed over 100 years, with sections of the cast iron facade removed and a metal fire escape added.

When the Museum undertook the first renovation of 213-215 Water in 1976, the main goal was to create a better gallery space on the first floor than was available in other 19th century buildings the Museum already occupied, as well as to alter the facade of the building with the oversight of New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

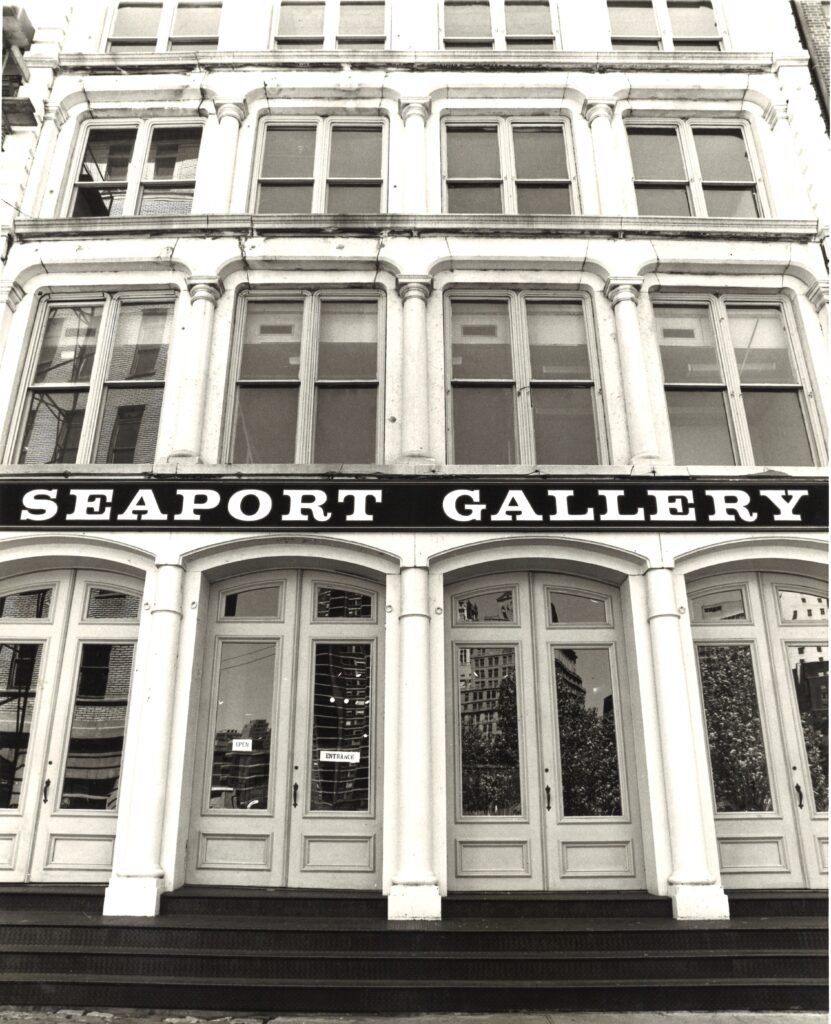

As an example of a building being given a name that reflects its use, when the newly renovated 213-215 Water Street opened in 1977, it opened as the “Seaport Gallery”. For the next 10 years the majority of the Museum’s large scale exhibitions would be installed and enjoyed by the public on the first floor.

The building had a large sign for “Seaport Gallery” above the doors, and the name would be repeated in Museum guides, maps, and in the Museum’s Seaport magazine until the 1990s.

However, the Museum would develop new gallery spaces throughout the campus in the coming decades, perhaps leading to a recognition that “Seaport Gallery” (or just “Museum Gallery”) was a bit too generic when new exhibition spaces came into existence.

Harry Walker, photographer. Seaport Gallery, June 1978. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

The Melville Gallery

When I started to work at the South Street Seaport Museum in the fall of 2015, the first floor of 213-215 Water Street was referred to as “Melville Gallery.” The name was in honor of the great American author Herman Melville (1819-1891) who was born, and spent most of his working life, in New York City. Melville’s best known works were informed by his experiences as a sailor on whaling, merchant, and United States Navy vessels. As a writer whose celebrated 1851 work Moby-Dick continues to be considered a Great American Novel, and whose oeuvre continues to inform popular perception of 19th century sail, Melville has remained a touchstone for preservationists and historians when talking about maritime New York.

The name was given to the 213-215 Water Street gallery in 1995, after the opening of two other gallery spaces in Museum buildings: the A.A. Low Building on John Street and the Whitman Gallery at 209 Water Street. The Whitman Gallery was named for another great American writer, Walt Whitman (1819-1892), who lived and worked in New York, and whose work is evocative for interpreting the 19th century today.

As resonant as Herman Melville can be for visitors, naming 213-215 Water Street after the author had some unintended consequences. Sometimes there would be confusion as to how Melville was connected to the building and we would get questions as to when he had lived or worked there. There is no record of Melville having occupied any building in what today is the South Street Seaport Historic District, and the fact that Melville lived and worked in several places in other parts of Lower Manhattan only muddied the waters. Since other Museum buildings are named for their 19th century occupants or builders—Schermerhorn Row for ship chandler Peter John Schermerhorn (1749-1826) and A.A. Low for China trade merchant Abiel Abbot Low (1811-1893)—it was thought best to return to that convention when describing 213-215 Water Street for its 2020s renovation.

Thompson Warehouse

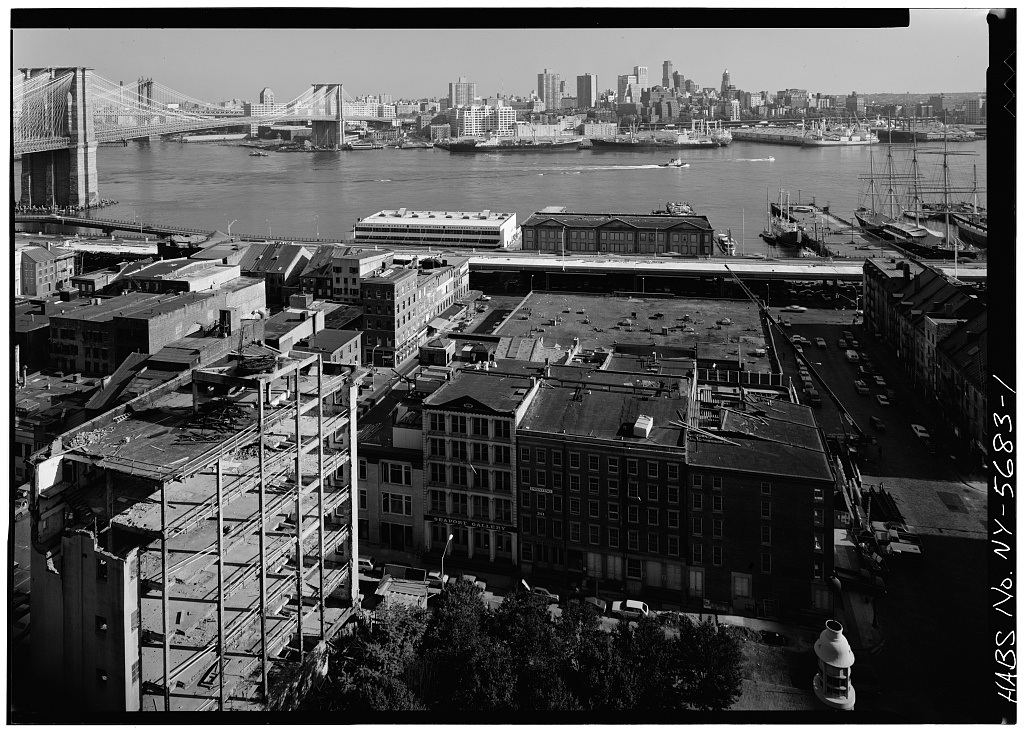

Historic American Building Survey. 207-209-211 Water Street in center foreground, 1976. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. HABS NY,31-NEYO,141–1

It was not hard to find the name of the first occupant of 213-215 Water Street. In 1976 a Historic American Building Survey (or HABS) was conducted by the National Park Service for the building. Started in 1933, HABS is an ongoing collaboration between NPS, the Library of Congress, and the private sector to document America’s built environment from Pre-Columbian sites to the 20th century structures. The Survey has produced more than 500,000 architectural drawings, photographs, and written histories for buildings across the country.

When describing the significance of 213-215 Water, the report states “This Italianate cast-iron and stone warehouse for tins and metals was designed by the renowned New York City architect Stephen D. Hatch in 1868 for A. A. Thompson & Co.” The report goes on to list the subsequent owners, documenting the building’s chain of title, citing the records of the New York City Conveyance Office as its source. The 1977 report that accompanied the designation of the South Street Seaport as a historic district reflected the findings of the HABS, stating, “This five-story Italianate warehouse was built for A.A. Thompson & Co., a tin and metals concern, and offers a striking contrast with the earlier Greek Revival buildings nearby.”

213-215 Water Street would go into the 2020s with the moniker Thompson Warehouse. But little did we know that the building itself was going to correct us.

The building tells us something

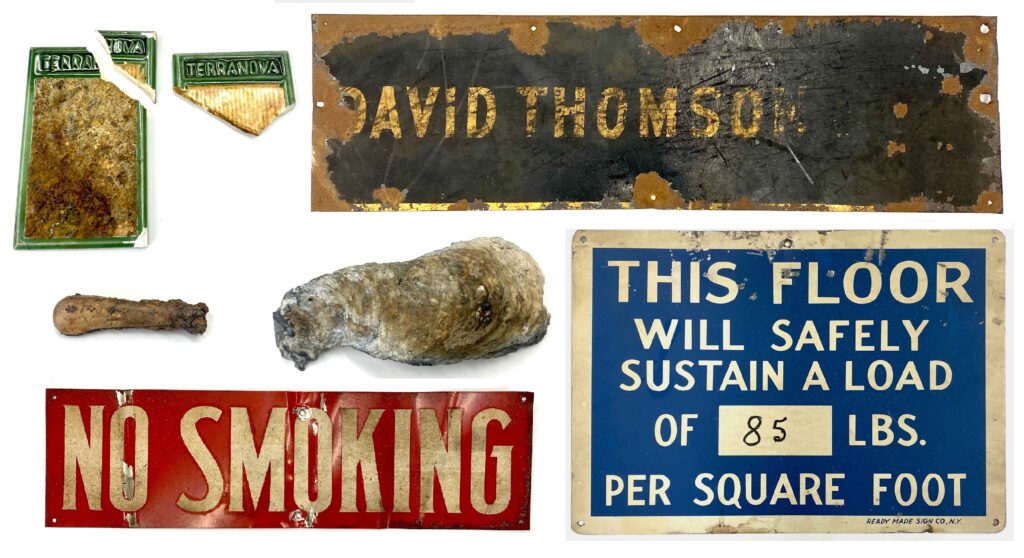

As the renovation got started in 2020, interesting artifacts kept being discovered in the walls, floors and foundations. Objects like an oyster shell and broken knife handle were reminders that the land Thompson Warehouse stood on was riverside landfill, while the mid 20th century occupancy and “No Smoking” signs spoke to the Warehouse’s past use in the commercial district. One sign, however, was a surprise, and it read: “DAVID THOMSON & Co.” Who was David Thomson? And was he somehow connected to A.A. Thompson?

[Found objects from Thomson Warehouse restoration], 18th century-mid 20th century. South Street Seaport Museum 2020.007 and 2021.004

A record of a David Thomson & Co. was found in the 1874 New York business directory, for the use of wholesale buyers, as sellers of refined tin at 215 Water Street. Though I didn’t initially find any proof of David Thomson being related to an A.A. Thompson/Thomson, this discovery demanded a second look.

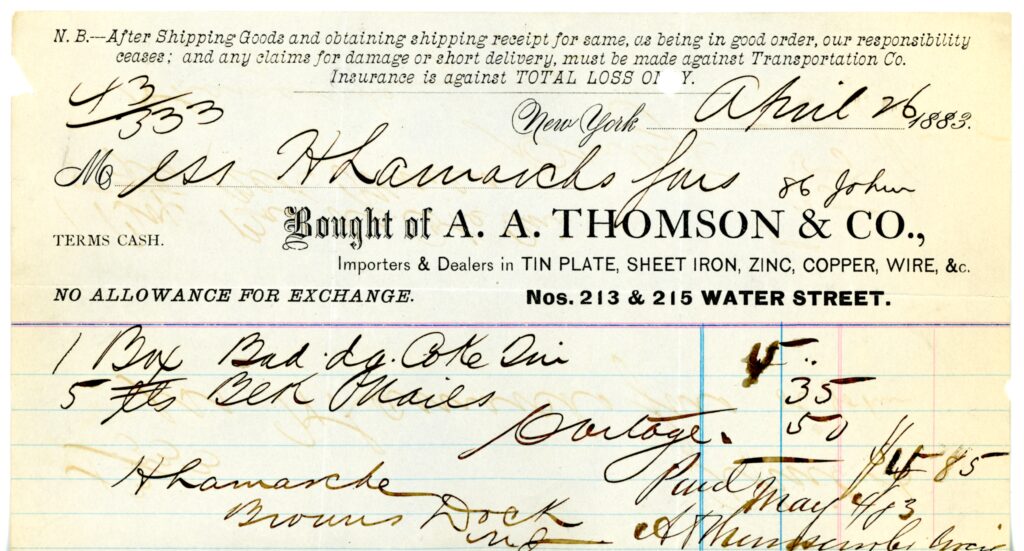

The answer was found in the South Street Seaport Museum’s collection. An 1883 billhead for A.A. Thomson & Co., metal dealers and importers at 213-215 Water Street, had been donated in 1999. The sign and the business document were then backed up by 19th century newspaper advertisements and a listing for A.A.Thomson in the same 1874 directory that listed David. A.A. Thomson’s name was certainly not spelled with a “p” as previously thought!

[Receipt, A.A. Thomson & Co.], April 26, 1883. Paper, ink. Gift of P. Gerald Nowicki 1999.018.0003

As a researcher, the best part of learning the correct spelling of A.A.Thomson’s name was that I could now find mentions of him and his business that I couldn’t when looking for “A.A. Thompson.” I was even able to locate an obituary for Alexander Archer Thomson (1833-1901) that was printed in the metal and hardware trade journal The Iron Age. The obituary describes A.A. Thomson & Co. as a firm that “…did a large business as importers of tin plates and metals, continuing in the same location, at 213 and 215 Water Street, from the beginning until now. David Thomson, another brother, joined the firm later and still continues as a member of it, together with W. Archer Thomson, a son of William Thomson, one of the original partners, who died in 1872.”

Thomson Today

After reviewing the evidence for changing the spelling of Thompson after nearly 50 years of preservation documentation, the Museum decided that the spelling used by the 19th century Thomson should be used to refer to his 1868 building. This has required some back-end clean up of the Museum’s website and records (so many digital files with the name “Thompson”) as well as writing up an official memorandum so that future Museum administrators will know why the change was made.

The most visible change to the nearly completed 213-215 Water Street building will be the sign above the door. When the doors open to the newly accessible gallery and event space, the lintel above will spell Thomson without the “p,” just as it would have in the 19th century.

Additional sources and reading materials

“Heritage Documentation Programs” National Parks Service, last updated May 5, 2022.

“HABS NY-5684: South Street Seaport Museum, 213-215 Water Street, New York County, NY” Library of Congress, documented and prepared 1976.

“South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report” City of New York and Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1977.

Herman Melville: A Biography by Herschel Parker, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

“A.A. Thomson & Co.” New York business directory, for the use of wholesale buyers, 1874, p. 84

“Alexander A. Thomson” Obituary, The Iron Age, April 4, 1901, p. 29.

“South Street Today” by John B. Hightower, South Street Reporter, Fall 1977.

“At the Museum” by I. Sheldon Posen, Seaport, Summer 1995 Seaport.

Learn About the 1868 Warehouse A.A. Thomson & Co.

Over 150 Years of History

This newly restored Italianate cast iron and stone warehouse, located at 213–215 Water Street has seen the evolution of New York City through more than 150 years. Learn more about the history of this architectural landmark designed by the renowned New York City architect Stephen D. Hatch (1839–1894) in 1868 for Alexander and William A. Thomson of A. A. Thomson & Co.

Inside the Thomson & Co. Restoration

Take a step back to 2021, when the restoration of the 1868 warehouse A.A. Thomson & Co. had just begun and watch layers of history peeling back to reveal secrets of the 19th century cast-iron building. This special virtual tour is led by South Street Seaport Museum President and CEO Capt. Jonathan Boulware shows and tells the process of renovating the historic building in the heart of the South Street Seaport Historic District.