A look into interactive pieces in Maritime City

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Carley Roche, Associate Registrar

March 27, 2025

Growing up in a large city, I was fortunate enough to visit many different types of museums and cultural institutions. Between field trips, city camps, and outings with my mom and sisters I probably visited every art gallery, historical museum, and science center in my hometown at least once a year. The visits that still stick out to me, more than several years later, are the ones in which I was able to fully immerse myself in the exhibits by touching and interacting with objects.

These experiences were typically at the science museum or in the kids’ area of history museums. I could step inside a real locomotive and pull any lever I wanted, climb the rigging of a ship, and dig through a sandbox for “dinosaur bones.” Although I never found a real pterodactyl as I had always hoped to, I still hold on to these memories dearly—and still very clearly. Interactive museum exhibitions provide visitors with a tactile experience that they can take with them for years to come.

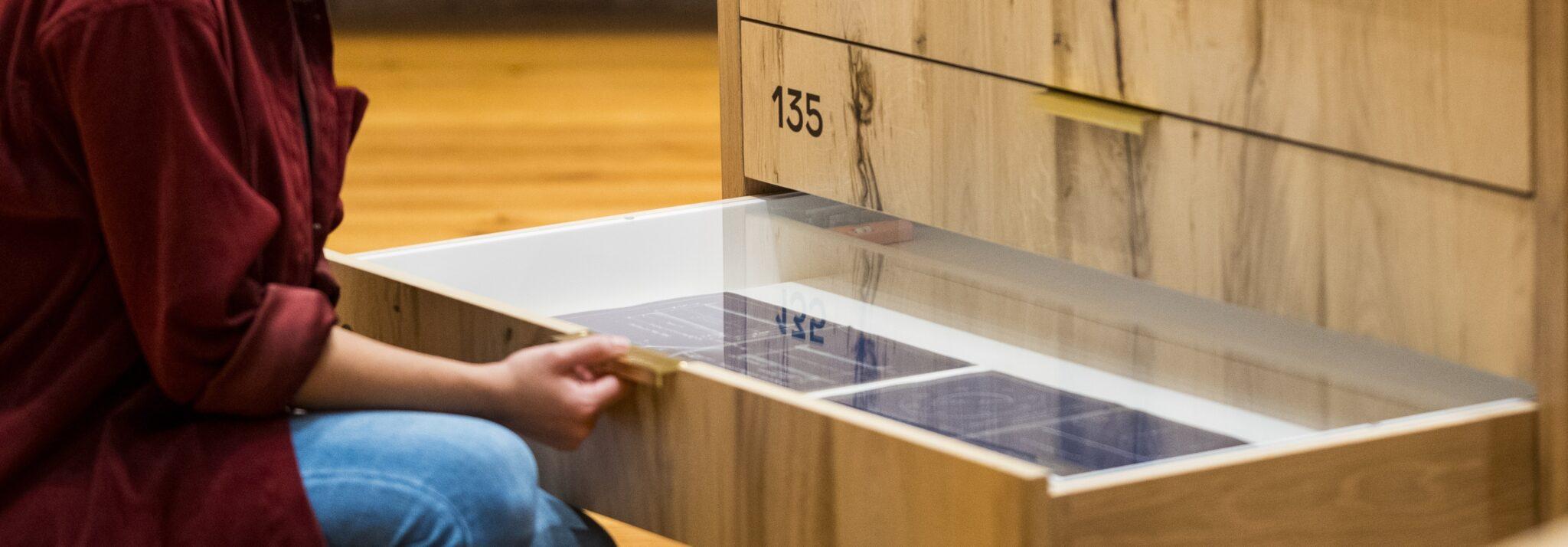

This notion of interactive exhibitions guided the curatorial working group who developed the South Street Seaport Museum’s newly-opened exhibition Maritime City. Located on the first three floors of the historic 1868 A.A. Thomson & Co. warehouse, the exhibit displays over 540 artifacts from the Museum’s collections. Throughout the show are several objects that visitors can physically touch, peer through, or engage with. In this blog post, I will be highlighting one specific type of interactive: the flat file. In Maritime City we have four of these types of interactive pieces of furniture that were specifically designed to offer a unique hands-on experience for visitors on the first floor gallery, housing in total 108 objects.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch

Interactive Museum Exhibits

When visiting museums, I’m sure you have seen signs that read “Please Do Not Touch” or noticed security officers standing guard over artifacts. I even recently experienced a local museum that implemented a pre-recorded voice that states “You are too close to the artwork. Please, step back.” if a guest stepped over tape adhered to the floor. These protective measures are there to protect the artifacts from potential human error. The natural oils on our hands, any buttons or pins on our clothes, or a simple misstep can cause damage to objects on display. So why are some artifacts and displays okay to touch while others are not?

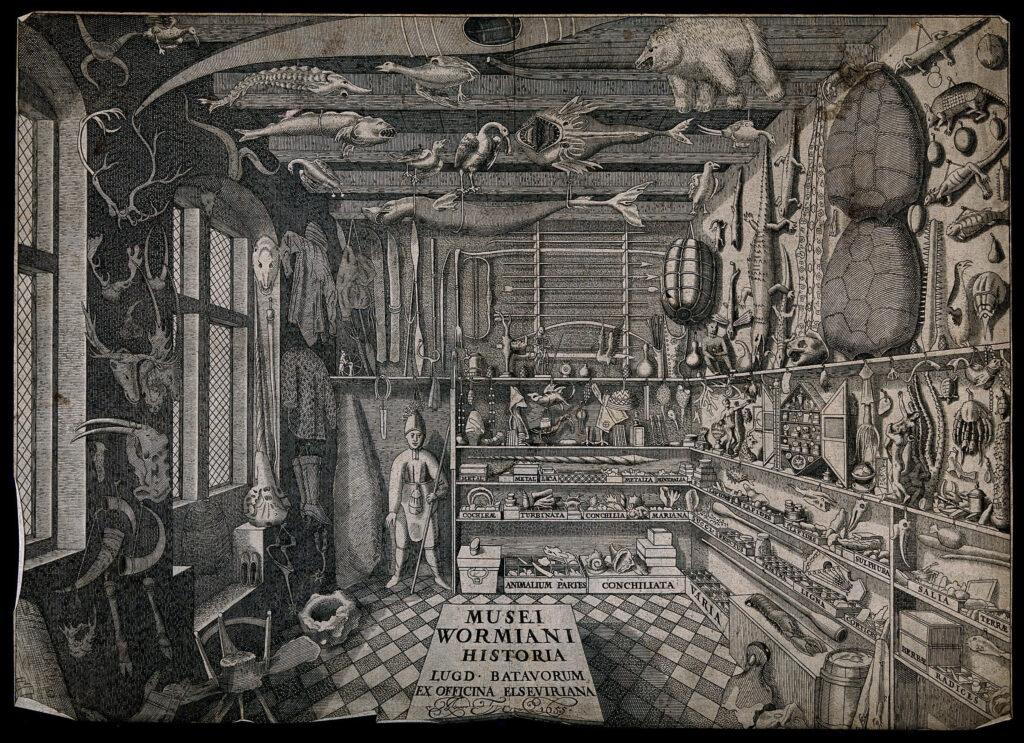

The predecessor to modern museums are considered to be Cabinets of Curiosities, rooms filled with objects popular throughout Europe beginning in the 17th century. These collections were typically privately owned by individuals or housed within society buildings. They often contained rare objects, largely unknown to the public, acquired through purchase or force during travels. Those who visited Cabinets of Curiosities were friends, family, and affluent society members who typically enjoyed a tour of the artifacts with a meal and were instructed to touch, pick up, and even move artifacts for their own pleasure. The allowance of touching collections increased in the 18th century with the advent of empirical philosophy by John Locke (1632–1704) in Great Britain. Reasoning that knowledge came from sensory experiences, these private collections became increasingly handled by visitors.

The museum of Ole Worm, Copenhagen: interior. Engraving, 1655. Wellcome Collection 571887i

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, collections began to open their doors to the general public. Due to the many social stigmas against the working class, caretakers of these collections pushed for new rules forbidding people from touching or interacting with artifacts. Further class biases pushed for museums and galleries to adopt sight as the main sense used by a visitor to enjoy collections rather than touch in the 19th century. Upper class society members caring for the collections believed laborers and the general public to be dirty and to not possess the mental acumen to understand the art, history, and science on display. To “assist” the lower class visitors, these early curators instructed the public to silently and simply view the artifacts leading to the notion of museums and galleries being gatekeepers of knowledge instead of places to share information with all.

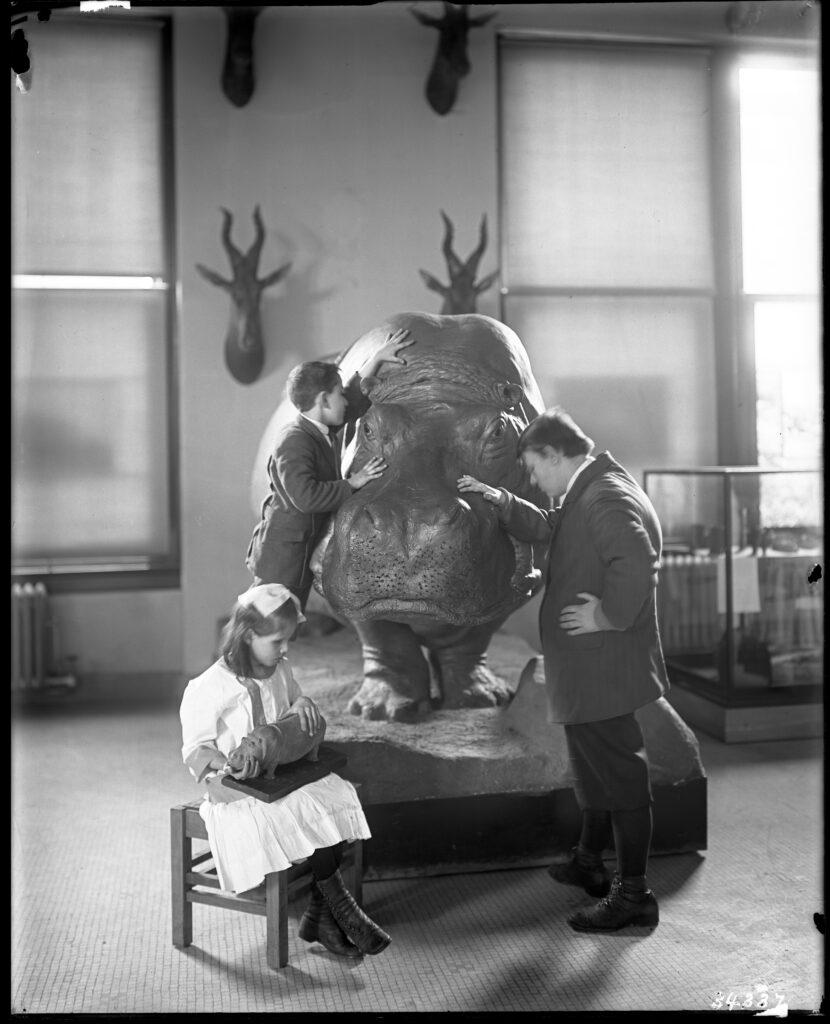

Touch reemerged in museums in the early 20th century as a means to allow blind visitors to “see” collections. The American Museum of Natural History here in New York City first opened a special experience in 1909 for visually impaired visitors by allowing them to touch and interact with real taxidermied specimens.

[Blind children examining the exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History]. Early 20th century. Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History, Gottesman Research Library.

The success of this exhibit led to the formation of lectures developed for blind and deaf visitors who could not have engaged with previously designed exhibits. By the 1970s, art museums around the world began experimenting with sculpture exhibitions to allow blind and low vision visitors to interact with their collections because sculptures tend to be more durable than prints, paintings, and watercolors. Finally, the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 helped to standardize the need for more interactive exhibitions making these more common than the simple 19th century viewing system.

In addition to accessible exhibitions, museums and galleries started adopting more interactive exhibits thanks to new technologies. Audio guides and 3D-printed models provide safe interaction with collections; virtual reality and touch screens provide hands-on memorable moments. During the development of Maritime City the curatorial working group chose to make the exhibition as accessible and engaging as possible by adding touchable objects and tablets, TV screens, viewers for 19th century technology, and, of course, the interactive flat files.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch and Richard Mitchell

Flat Files

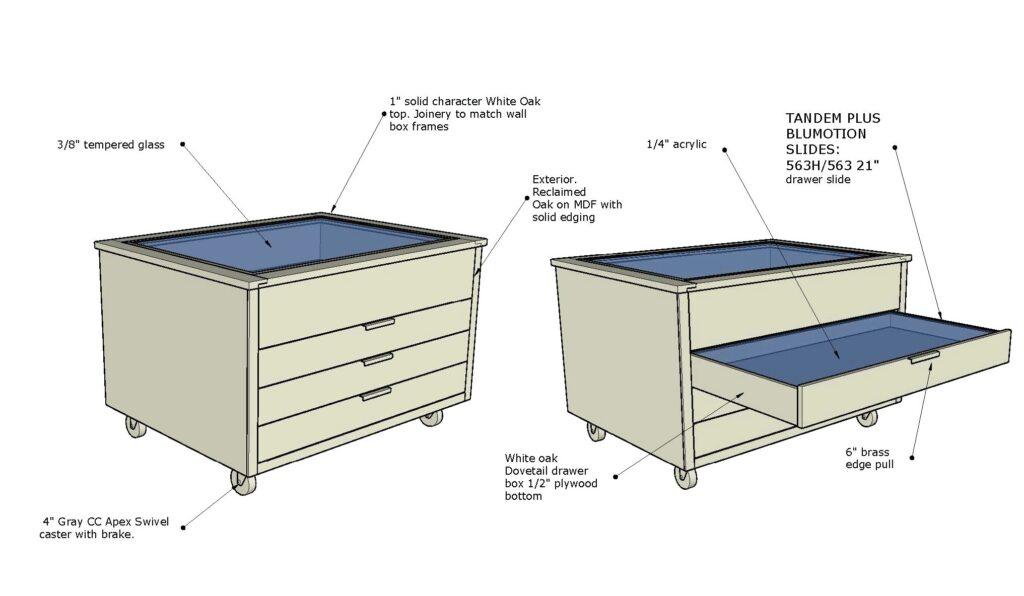

The idea of using flat files as interactive furniture pieces first appeared in the early meetings of Maritime City’s conceptualization. From the beginning, Museum staff and architects from Marvel, who were in charge of design and concept for the show, agreed that the flat files would be located in the open space on the first floor for two main reasons. First, the flat files would showcase objects that do not necessarily fit into the themes of objects on the second and third floors. Second, knowing that this space would also be used for public programs and events, the Museum needed the flat files to be mobile to accommodate the safe and easy relocation of the objects housed within the four flat files. With this in mind, each flat file was designed to have swivel caster wheels with locking brakes and fit perfectly through the gallery doors and the elevator.

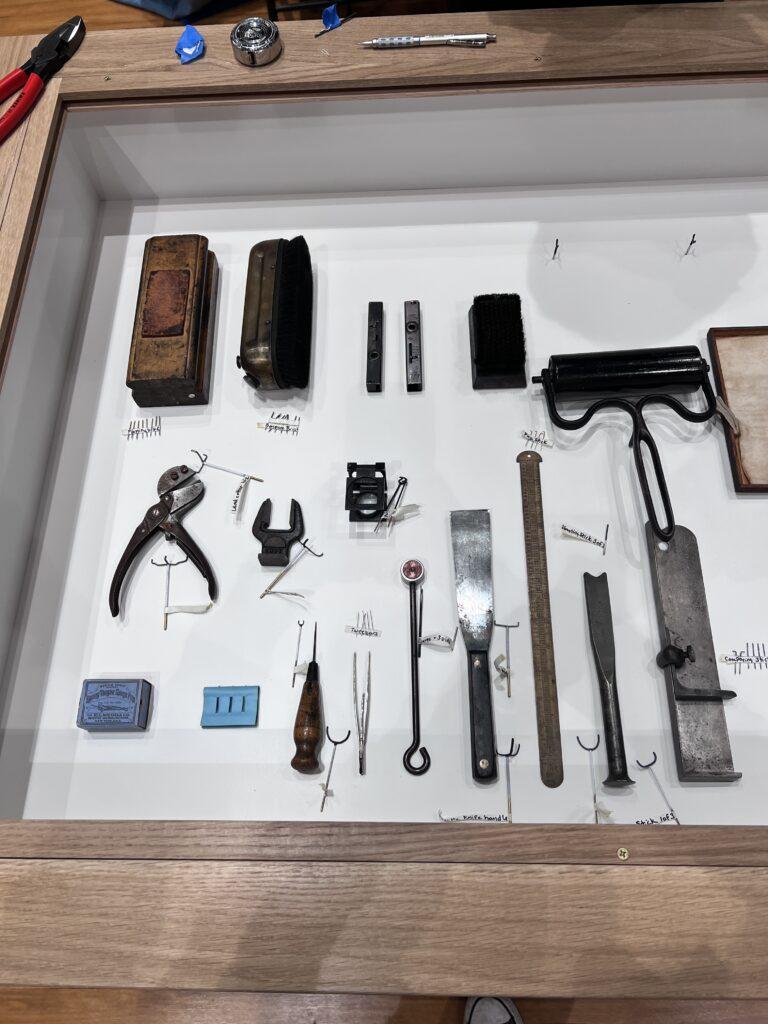

Thanks to the work of Marvel and South Side Design & Building, who fabricated all of the exhibition’s casework, the final product has become a shining aspect of Maritime City. Each flat file is made of refined oak wood with brass handles to match the aesthetic of the displays and accessories found throughout the exhibit. A clear glass top shows visitors various tools used for each trade, and right below within the flat files are three drawers that allow visitors to literally pull out examples of what the craftsperson created using the tools seen on top. All four flat files have interiors made of komacel, a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) foam board that is museum-safe as it protects artifacts from pests and is sturdy enough for art handlers and mount makers to secure objects to it.

Eventually, it was decided that the content in the flat file would represent a trade and crafting technique as key components of creativity in New York: drawing and drafting, wood carving and wood engraving, letterpress printing, and lithography production.

Knowing that these flat files were meant to be mobile, the objects themselves are secured in place without fear of rolling around or jumping out of place thanks to the incredible mounts created by ObjectMounts for the exhibition. (Read more about the mount making process in the Collections Chronicles Blog post Put on a Pedestal.) If you look closely you can see the brass mounts securing the tools in place.

The flat works are also fixed in place, but how this is done is more difficult to see. What is visible are the archival backboards each work is mounted to, which gives the paper works more stability. These archival boards are then fixed in place with an archival adhesive with a very high bond, so it is called VHB tape. This product is then carefully secured to the bottom of each drawer. VHB tape is safe enough to use near paper artifacts and strong enough to keep any artifacts from blowing away.

It has taken a well-coordinated team to make the flat files such a success. Now that we understand how they were made and how they protect the artifacts, let’s dive into the history of each trade found within their drawers.

Drawing and Drafting

What do the French, compasses, and ducks have in common? These terms all relate to the tools used to make precise and accurate technical drawings for constructing buildings, ships, and other structures. While the technology has changed over the millennia of drafting’s history, its importance in building modern society cannot be overstated.

When humans began to form what we consider today to be structured societies they needed to plan what they would build. It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact beginnings of the drawing and drafting trade as written history is a relatively new concept. Archaeological research has unearthed ancient tools used for construction, but the plans themselves have been more difficult to track. One of the earliest examples of engineering plans is from a fossilized record showing an aerial view of a Babylonian castle from around 2000 BCE. Around this time, the Sumerian prince Gudea (d. ca. 2124 BCE) also ordered the construction of temples to the Gods, which we know thanks to a statue of Gudea on view at The Louvre. This artifact provides modern historians with the first example of drafting tools in use seen on Gudea’s lap.

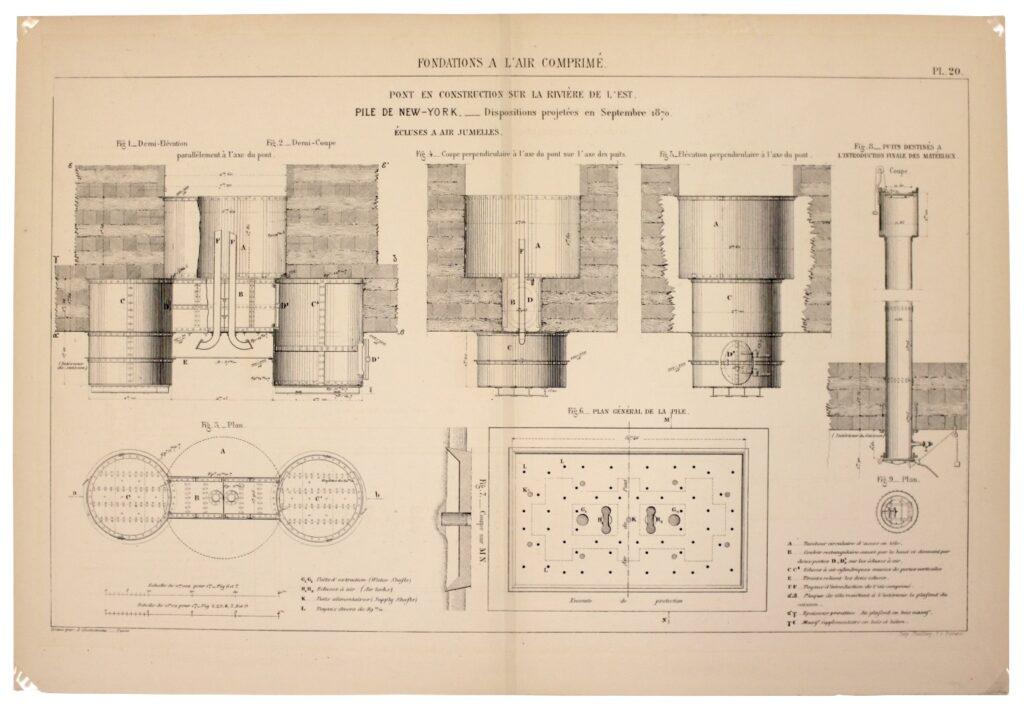

The artifacts on display in this first flat file are certainly not thousands of years old, rather they date to the 19th and mid-20th centuries. Some of the most eye-catching tools in the top display are the various wooden, flat, curved pieces known as French curves. Invented by German mathematician Ludwig Burmester (1840–1927), these curves can have many shapes to aid in the manual drafting of designs with curves that have changing radii. Above the text you can see a case holding three small metal compasses used to draw accurate circles and arches. Along the bottom of the display you will find more compasses as well as dividers, which are aptly named for their use in dividing line segments. Finally, the left side of the display shows three ducks—lead weights shaped like ducks that hold a curve in place for tracing.

When you visit Maritime City, pull open the drawers to reveal detailed technical drawings, blue prints, and ship plans made with similar drawing and drafting tools.

Right: Émile Malézieux (1822-1885); Dunod, publisher; Fraillery et Cie, printer. “Fondations a L’air Comprime Diagrams” 1875; September 1870 (original). South Street Seaport Museum Archives 2000.018.0029

Wood Carving and Wood Engraving

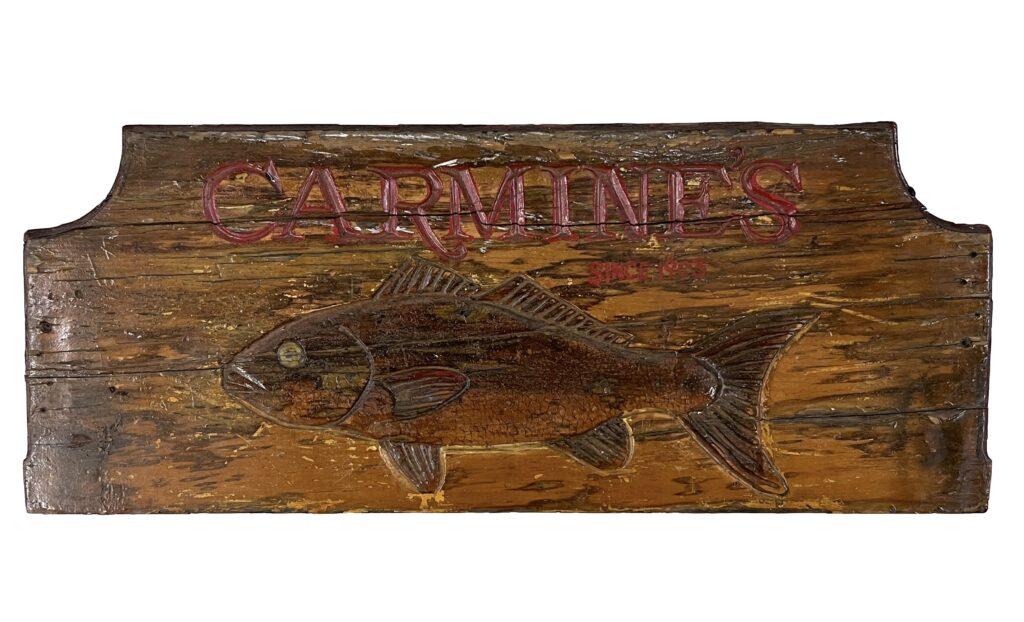

The next flat file we will be looking at actually represents two different methods of working with wood: carving and engraving. Although both carvers and engravers use wood—the tools and processes are different. The main distinction between them is carving is the process of chiseling and sculpting away material to form a desired shape, while engraving is making fine scratches into wood to create a design for printing and art making.

People have been carving wood into tools, weapons, and iconography since prehistoric times. The oldest known worked wooden instrument—the Clacton Spear—is approximately 400,000 years old. Carvers can utilize either soft or hard wood based on their needs and skills, but some of the most popular choices are basswood, oak, walnut, and maple.

Wood engraving’s history is shorter dating back to the late 18th century with its development credited to English natural historian Thomas Bewick (1753–1828). Engraving specifically utilizes the end grain of wood due to its tightness allowing for more refined work. Unlike carving, engraving requires the use of hardwood only making boxwood one of the most popular choices.

From the small burins used to scratch out detailed etchings to the large mallet needed to carve with a little extra force, the tools you see on display in this flat file represent the labor that goes into both crafts. Many of the tools you see were kindly donated to the collections in 2019 after the passing of the longtime friend and Master wood carver of the Seaport Museum Salvatore Polisi (1935–2015). Starting in the mid-1980s, Polisi spent six days a week at the Museum thus becoming an integral member of the community in the neighborhood. He carved wooden signs, statues, figureheads, and more for the Museum’s ships as well as local businesses and clients. Polisi loved explaining his beloved craft to Museum visitors, so it is wonderful to be able to have his tools on view and continue his legacy in explaining the connections of wood carving and the maritime world.

Right: Salvatore Polisi (1935-2015), “Carmine’s Restaurant Fish Sign” ca. 1980s. Courtesy of The Molini Family 2015.IL.CAR.002

Letterpress Printing

Where would we be as a society without printing technology? Providing a way for people to relatively quickly distribute information, news, and ideas—as opposed to hand-copying texts—printing has been an essential trade for centuries. The origin of this technology is difficult to date, but the 868 CE Buddhist book The Diamond Sutra from Dunhuang, China, is believed to be the oldest printed book in existence. However, western civilization credits German inventor Johannes Gutenberg (d. 1468) with the invention of printing—nearly 600 years later in ca. 1440 CE—because of his printing press design. Ushering in an “information revolution” Gutenberg’s machine and process involves inking moveable type and carved images then pressing these onto paper.

The Seaport Museum has its own long history with letterpress printing thanks to Bowne & Co., Stationers, which originally opened in 1775 making it one of the oldest printing firms in New York. Located at 211 Water Street since 1975, the active print shop gives hands-on lessons on letterpress printing with historic presses and the history of font types in monthly and seasonal workshops.

Photo Credit Richard Bowditch

If you don’t want to get your hands a little dirty then you can still have an interactive experience with letterpress tools and flat works in this next flat file. On display are most of the tools used in this process (except for the printing press itself, which you can find on the exhibition’s second floor!). Tools such as the composing stick help the printer organize the necessary letters and characters before they are inked and pressed and the ink roller and palette knife help spread the desired ink colors onto the press.

Letterpress printing is an arduous task requiring hours of labor to create a single page of paper that can be quickly reprinted. When you open the drawers beneath the tools you will find both informative and artistic examples of this process. Keep an eye out for the works of Robert Warner (1956–2023) in one of the drawers. Former Shopkeeper and Master Printer at Bowne & Co., Stationers, Warner’s journey with the Museum began in 1995. Warner learned how to print while working here and with his artistic background he crafted his own colorful and enriching legacy. It is exciting to have his creative talents continue to touch visitors as they interact with this flat file.

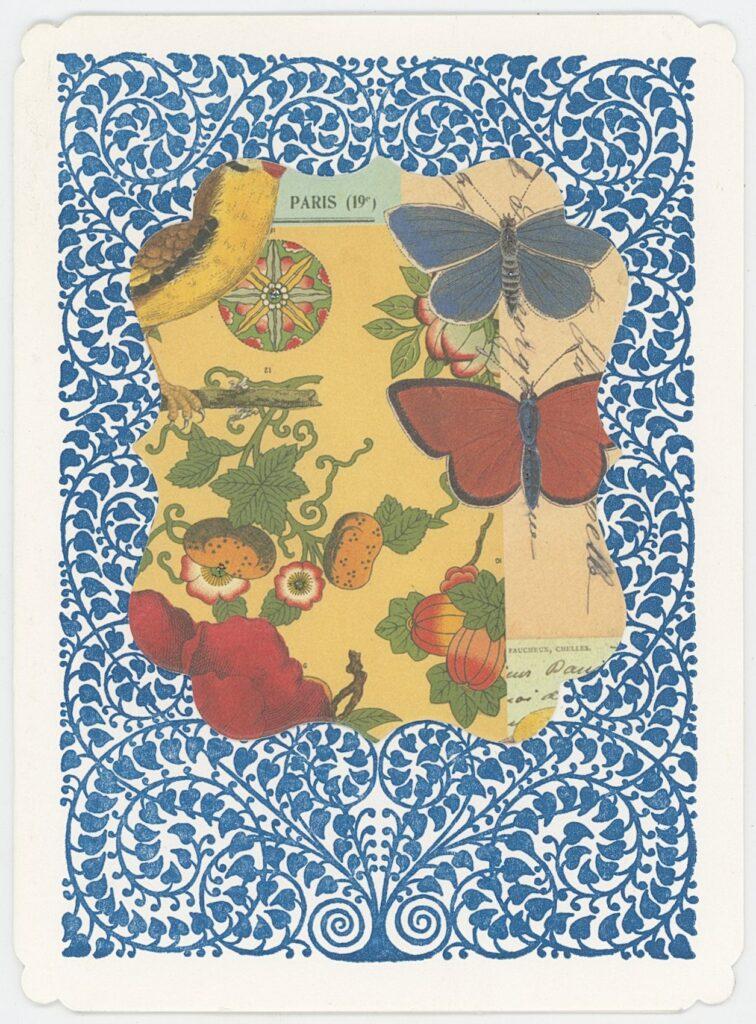

Right: “Untitled Collage Notecard” ca. 1990-2020. Robert Warner Works on Paper Collection, 2023.008.0322

Lithography Production

Having lived in New York City for over five years, I’ve met my fair share of “starving artists.” I have yet to meet one, however, who has accidentally invented an entirely new printing process that revolutionized the art world.

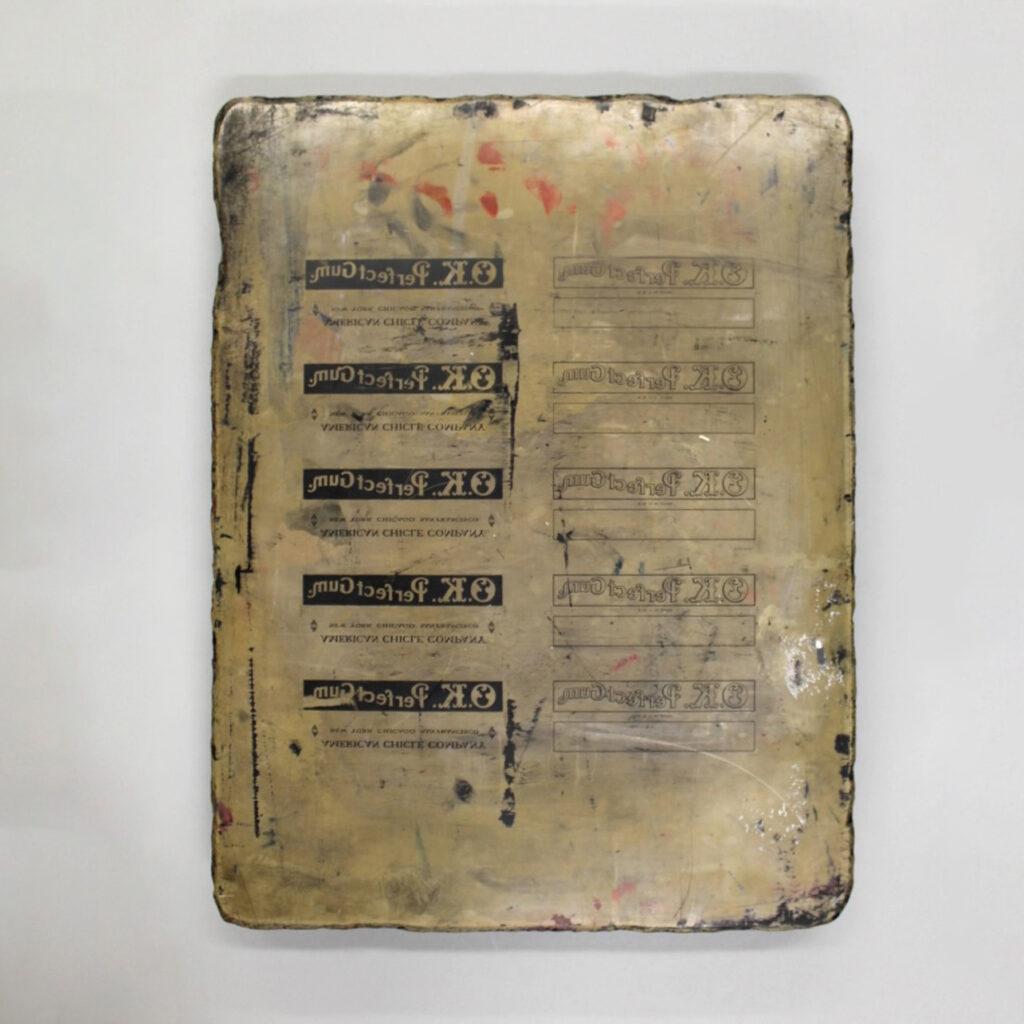

This final flat file is dedicated to the printing process of lithography, which was discovered around 1796 by Bavarian playwright Alois Senefelder (1771–1834). Unable to afford the prices of commercial printing offices Senefelder taught himself to print in order to publish his own plays in hopes of getting them purchased. Unfortunately, Senefelder did not find success with his engraving skills on copper plates. Writing down a literal quick laundry list one day with a grease pencil on a slab of local limestone, Senefelder realized he could etch around the words to make them a relief and copy the words onto paper—thus lithography was created.

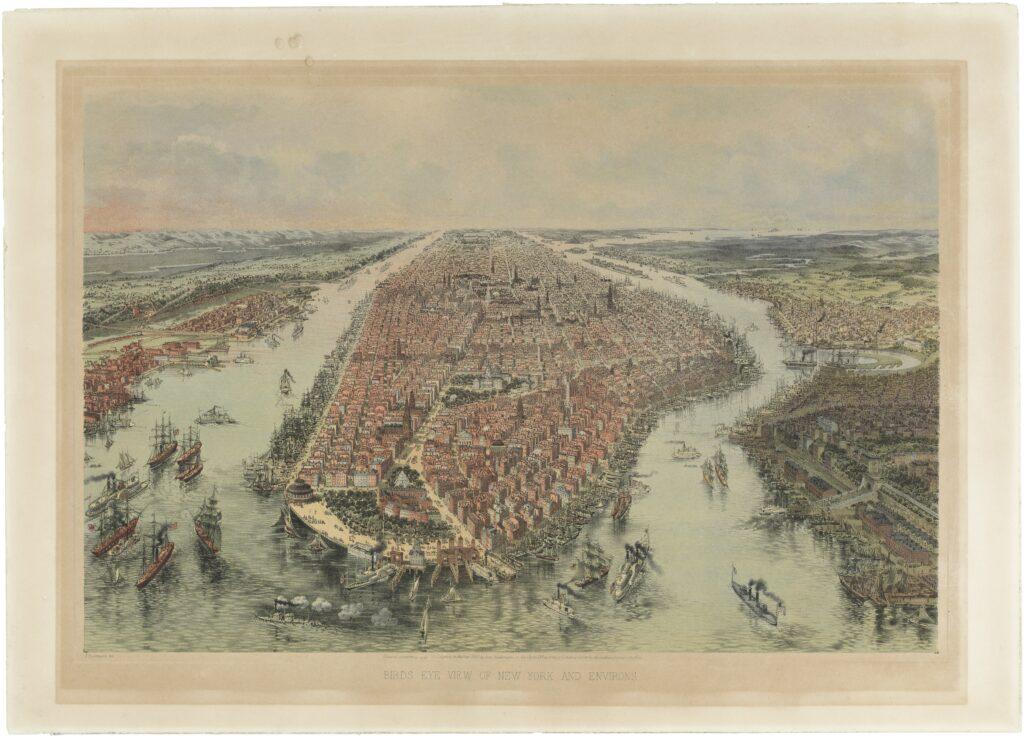

Lithographs became increasingly popular amongst 19th century artists because they were easier to produce than engravings and woodcuts. The substantially cheaper cost also made them accessible to more artists and businesses. In the 1880s the process was further developed with the creation of multi-colored lithographs. This process greatly expanded advertising opportunities and allowed portrait artists to print more realistic works.

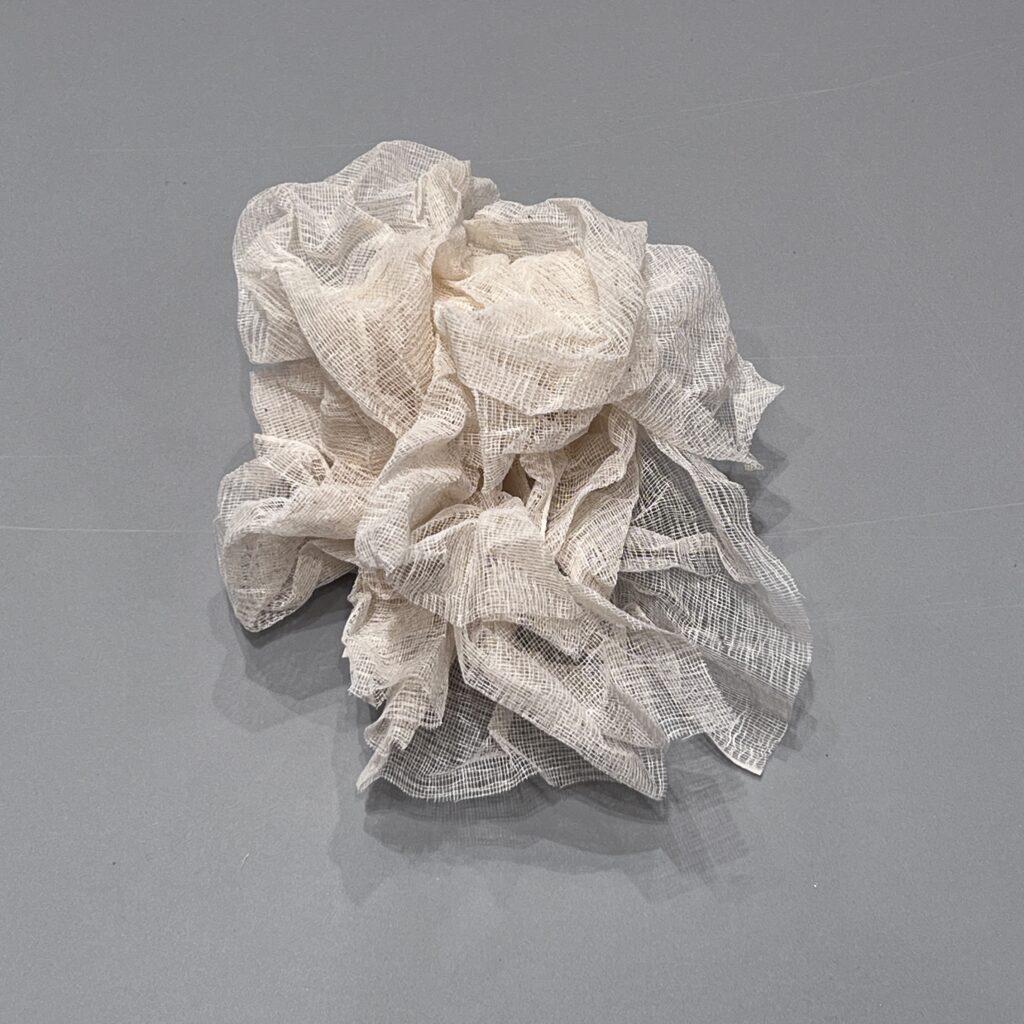

Making a lithograph is more technical than a quick drawing on stone and copying it onto paper. It uses specific chemical reactions to affix a drawn image onto a flat limestone surface (or a prepared metal plate, usually made of zinc or aluminum) and specialized crayons and ink to create the image. And should there be an excessive amount of ink a tarlatan cloth can help blot it away before the final product is finished. All of these tools and a selection of brightly colored lithographs are available to see within the drawers of this flat file.

John Bachmann (1814-1896). “Birds Eye View of New York and Environs” 1865. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 1991.070.0204

A Delicate Balance Achieved

I’ve always been a believer in history being seen as tactile because it is happening around us at every moment. However, in my field, I also need to ensure history is preserved and conserved properly through artifacts so it can be studied and enjoyed for generations to come. It is a delicate balance that I believe we found while developing Maritime City. So the young girl playing in a real locomotive and discovering fake dinosaur bones would be ecstatic to know she played a role in creating this sprawling interactive exhibit.

And please remember, although some of these objects can be touched and interacted with, it is important to not move them from their current location. Injuries to either the visitor or the artifacts is not something we hope to ever see.

Now, without further ado, as a Seaport Museum staff member I can go against the stereotypes and tell you to “please, touch!”

Photo credit Richard Mitchell

Additional Readings and Resources

“The Blind in the American Museum” by Agnes Laidlaw Vaughan, American Museum Journal, January 1914.

“The History of Interactive Multimedia in Museums” Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993, pp. 9-15.

“Draughting Curves in Ship Design” by Jobst Lessenich, Creating Shapes in Civil and Naval Architecture, June 30, 2009, pp. 425–434.

“The Clacton Spear: the last 100 years” by Lu Allington-Jones, Archaeological Journal, Vol. 00, No. 00, 1–24, March 2015.

“Lithograph” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018.

“Please Touch: The History of Museum Accessibility for Blind Visitors” by Claudia E. Haines, July 27, 2021.

“A brief history of (not) touching art” by Matthew Lamb, January 9, 2022.