The rise of marine libraries and sailor literature

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections & Curatorial Assistant

March 31, 2022

As the Collections and Curatorial Assistant I’ve written a few blogs about the different collections I get to work with and the many stories they can tell us about New York City and the people that have lived, worked, and traveled around the city’s waterways. The Museum began collecting artworks, artifacts, and archival materials from its earliest days in the late 1960s, developing a varied collection that could be used for exhibition, research, and even for the preservation of the skills of the working waterfront and printing offices. When thinking of what I should write about next for the Collections Chronicles blog entry I realized there was one foundational collection that we had not yet touched on: the Museum’s Library and its many books.

When I was first inspired to highlight the Library, and specifically examples from the Rare Book Collection, I was thinking back to the isolation we went through during the early peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the best escapes was having a good book to read (as well as a book club that continued to meet over Zoom.) Though the popular image of seamen in the Age of Sail usually features them fighting fierce storms and pirates, it’s less commonly acknowledged that sailors were a uniquely literate working population in the 19th century.

Ocean-going sailors in the centuries before radio and satellite communication could spend months, even years, at sea. All kinds of books could be found at sea: along with consulting navigational and other practical books needed to safely run a vessel, reading was also a leisure activity available to sailors when they were physically isolated from the rest of the world.

But sailors didn’t always need to buy books themselves: during the early 19th century, coinciding with the rise of industrial book printing, charities that were worried about the religious and moral development of sailors took interest in what was being read on ships. Groups were formed to provide books and magazines, or even full libraries, to vessels.

Sailors also contributed to book culture and some would find literary success as authors. “Sailor narratives” became a popular genre as sailors’ experiences were both exciting and exotic for land based audiences as well as avidly read by fellow seamen.

Sailors and charitable organizations also used the power of print to advocate for better working conditions and as a tool for labor organization into the 20th century.

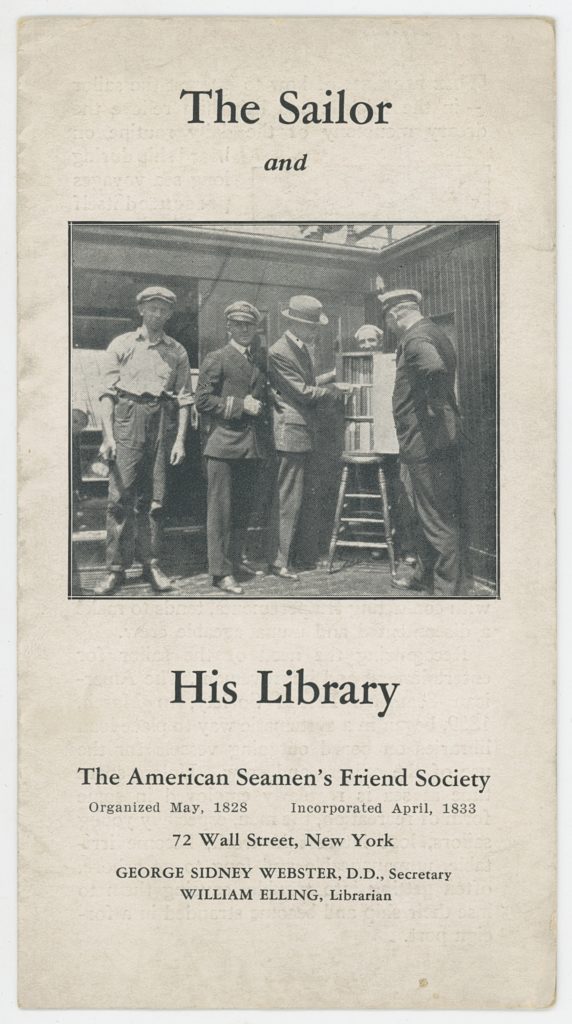

“The Sailor and His Library”, early 20th century, published by the American Seamen’s Friend Society, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

In short, the maritime world was also a literary world. Though I cannot adequately cover the many facets of books and sailors, this blog post is a quick look at a few examples from the Museum’s current collections and archives that show us a little bit about the printed word at sea.

The Useful Book

Before the 1800s, an American or European ship would rarely have more than a few books for the professional use of the ship’s master and officers. These would have consisted of a few printed navigational guides, mathematical and astronomical treatises, and maybe a book on medicine in case of injury or sickness. A Bible or prayer book were also commonly carried as Christian religious ritual was greatly adjusted for life at sea, but nonetheless considered a necessity.

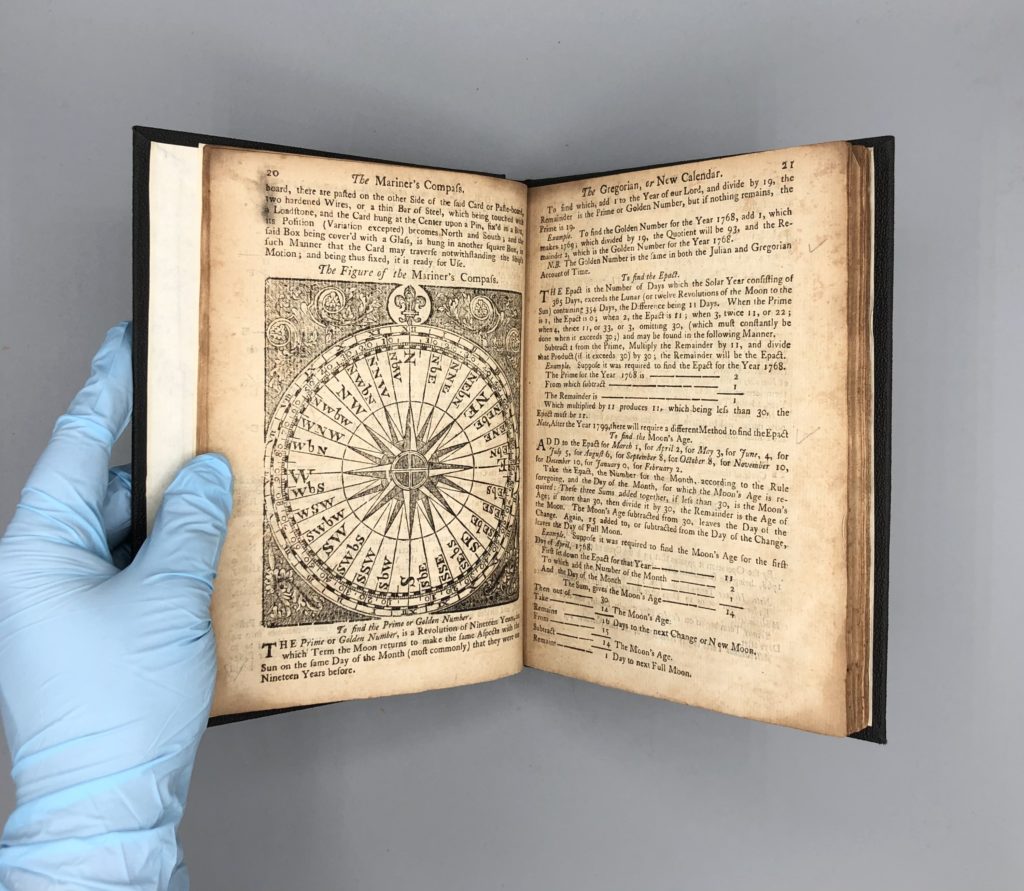

Some of the oldest books in our Rare Book Collection, from the 17th and 18th centuries, fall into this category. This 1768 edition of The Mariner’s New Calendar[1]Book titles are shortened in this blog post for readability. For example, the full title for this work would be The Mariner’s New Calendar. Containing The Principles of Arithmetic and Practical … Continue reading by Nathaniel Colson (credited on the title page as “Student in Mathematics”) covers many topics critical for navigation including “The Deſcription and Uſe of the Sea-Quadrant”; “A Tide Table”; and “Aſcenſion and Declination of the Principal Fixed Stars.”

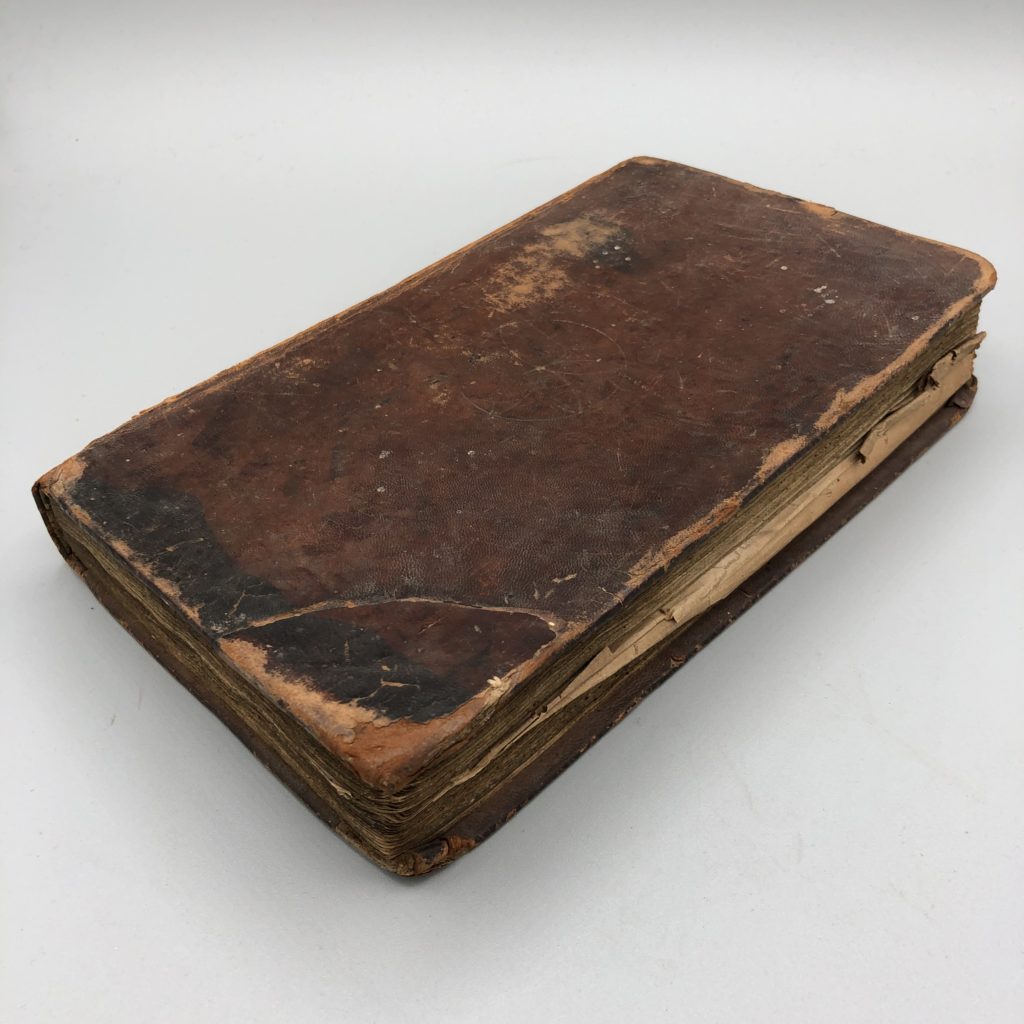

The Mariner’s New Calendar by Nathaniel Colson; revised by William Mountaine, 1768, published by J. Mount and T. Page. South Street Seaport Rare Book Collection

The volume also includes guides on how to navigate several major European harbors to avoid shallows and other hazards. Whole book series, often called “pilots”, were printed for navigating specific waters—usually relying almost entirely on written directions until book illustration became less expensive. The first of these published in the United States was Edmund March Blunt’s (1770-1862) American Coast Pilot, in 1796, in Massachusetts.

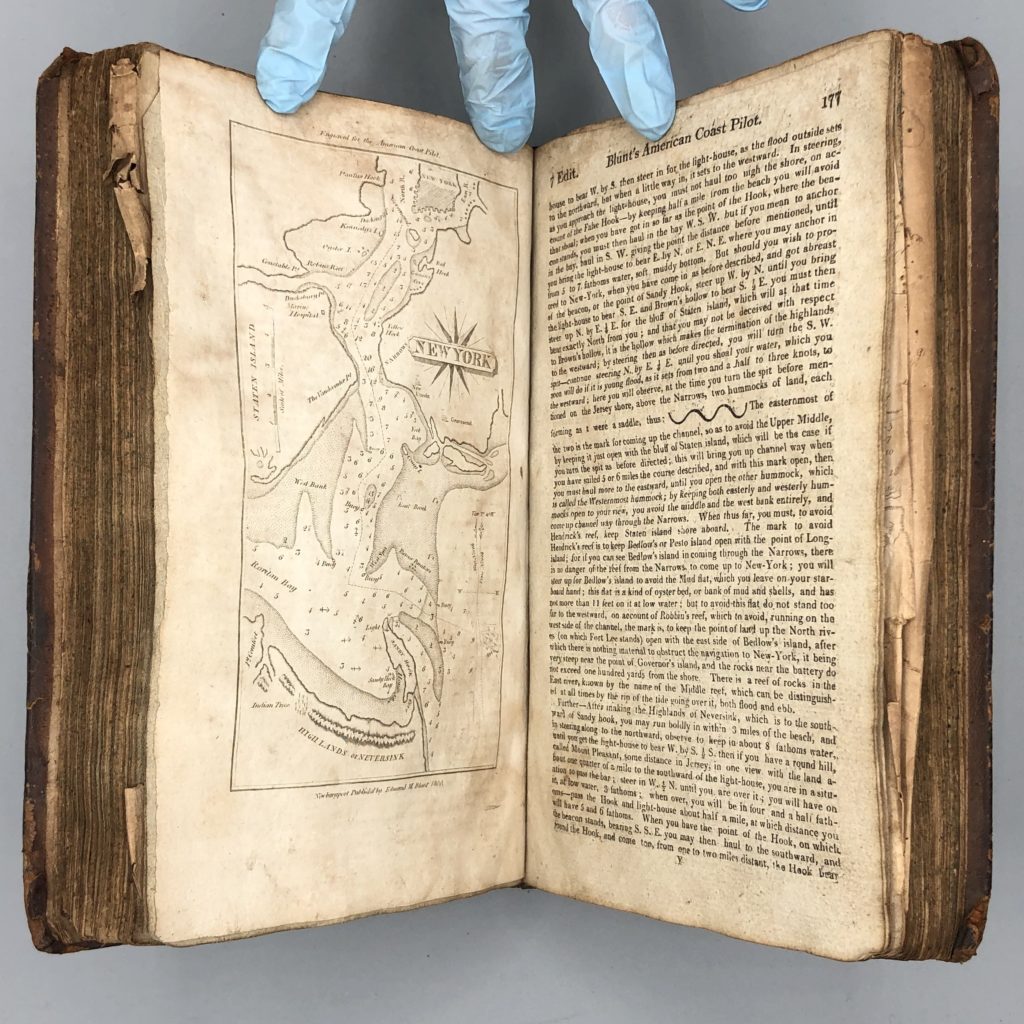

The American Coast Pilot attributed to Captain Lawrence Furlong, 7th edition, ca. 1812, published by Edmund M. Blunt. South Street Seaport Rare Book Collection

By the time Blunt published his 7th edition of American Coast Pilot, he had moved to 202 Water Street, just outside of what is today the South Street Seaport Historic District. Blunt included engraved charts of major ports throughout the Pilot, but the text itself is incredibly illustrative: “…you will steer up for Bedlow’s island to avoid the Mud flat, which you will leave on your starboard hand ; this flat is kind of oyster bed, or bank of mud and shells, and has not more than 11 feet on it at low water ; but to avoid this flat do not stand too far to the westward, on account of Robbin’s reef…” The American Coast Pilot is still being published today by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as the United States Coast Pilot, to provide information important to navigators of coastal and intracoastal waters and the Great Lakes.

Though the potential for danger at sea can be inferred from some of the navigation books that could be found on ships, this medical text illustrates them frankly. A sick or injured seaman or passenger on a 19th-century vessel faced hard prospects. Sailors could suffer from tuberculosis, malaria, work-induced hernias and broken limbs, and other afflictions. Mariners confronted rudimentary medical treatment at the hands of ships’ surgeons, with little or no effective anesthesia.

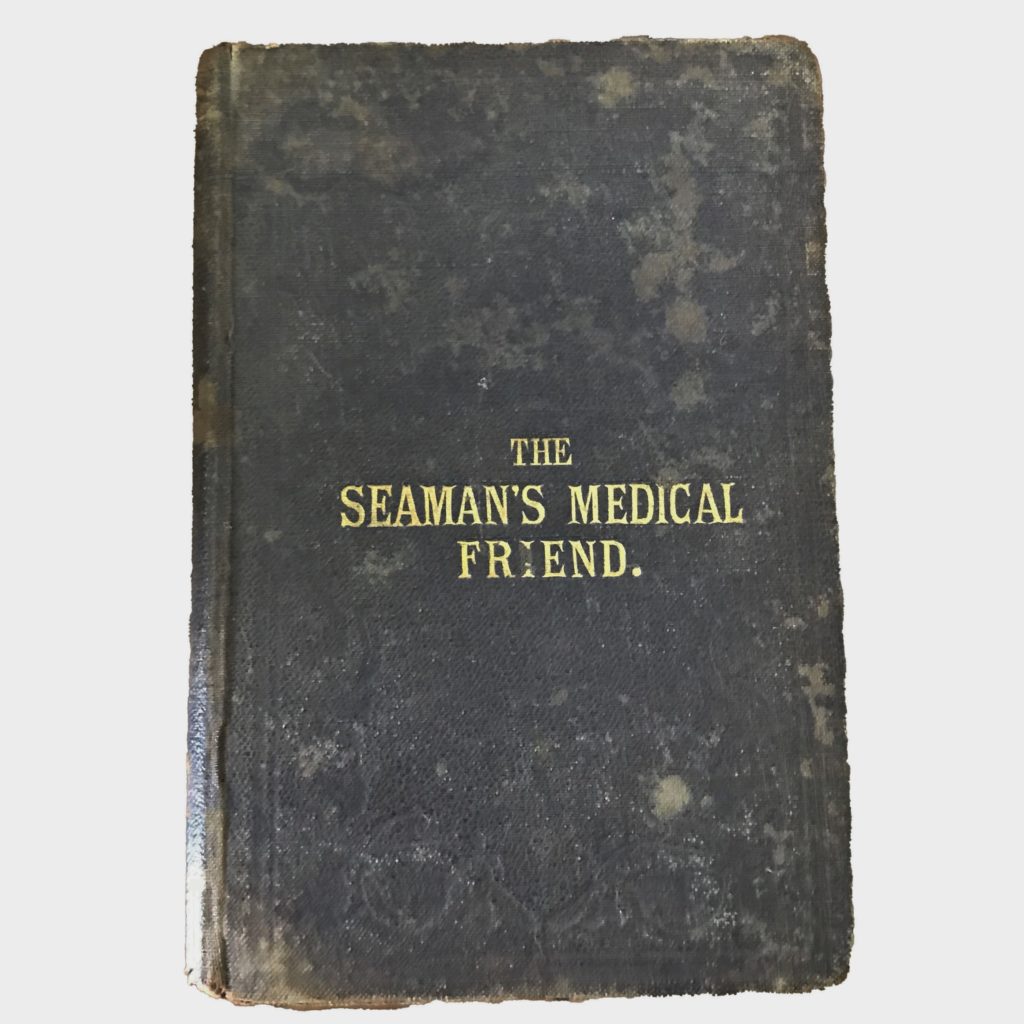

This ca. 1860s edition of The Seamen’s Medical Friend by Frederick D. Fletcher (used on board the New Bedford whaleship Cherokee) opens with a list of medicines that should be kept in the ship’s medicine chest, and goes on to prescribe treatments for the diseases and injuries mentioned above.

The Seaman’s Medical Friend by Frederick D. Fletcher, ca. 1860s, published by Fearnall and Co. Gift of the J. Aron Charitable Foundation, 1988.075.0118

The text is clearly written for ship’s captains and officers, as some sections include how the sailor’s labor needs to be adjusted or managed while they were injured. Interestingly, Fletcher also writes about the need for mental exercise for sailors: “The ordinary work of a sailor will generally furnish as much as is required for bodily health; but it must not be forgotten that a healthy condition of the mind is required…and therefore it is of great importance, especially for sailors, to have some means of occupying their mind…No ship, therefore, ought be without a good supply of books.”

If these were the books needed by the ship’s captain and officers for the safe operation of their vessels, what were the ordinary seamen reading?

Charities and Reformers

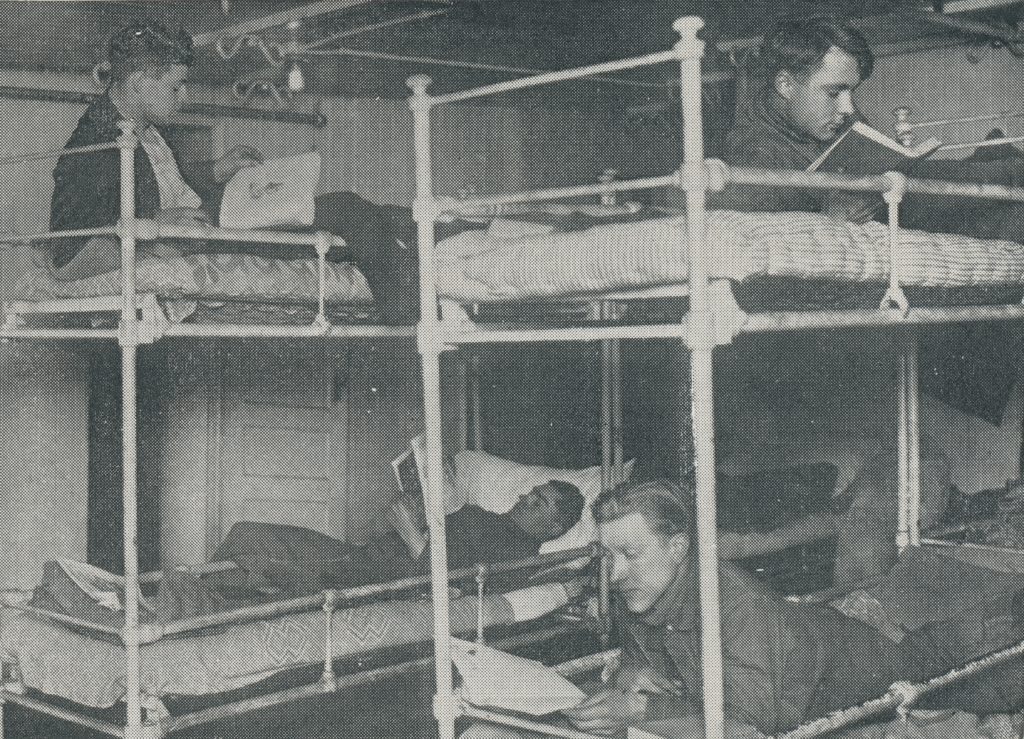

Detail of “Pleasant Hours in the Forecastle” from the American Seamen’s Friend Society 94th Annual Report, 1922. South Street Seaport Reference Archives

Though the examples above demonstrate there were certainly practical books at sea for centuries, there were no “ships libraries” for the ordinary seaman before the 19th century. Literate sailors would have to bring their own books on board, and possibly acquire new books by trading with crewmates. Reading aloud was another way sailors shared the limited reading material on board with each other. Concerted efforts to provide books at sea for common sailors greatly expanded in the 1820s. Religious organizations, such as the New York City founded American Seamen’s Friend Society and Seamen’s Church Institute, were some of the first to promote literature for American sailors, since they were concerned about preserving the seaman’s Christian soul and providing resources to save the sailor from a life of sin while in port or at sea. Though these charities often advocated for better working conditions and protection for sailors, much of the writing from these organizations also paint a patronizing picture of seamen; it’s worth noting that these charities focused on providing reading material for seamen because sailors were known to be voracious readers before the early 19th century reform movements.

The American Seamen’s Friend Society was founded in New York City in 1825, and its 1828 constitution called for libraries, boarding houses and reading rooms to be established in major ports around the world. To get books on the ships themselves, the Society created portable book boxes or cases filled with sixty to eighty volumes- initially supplied by the evangelical American Tract Society and individual donors. By 1839, 159 vessels had been supplied with a “Sailor Library.” These permanent libraries were later converted to a loaning library system, so that the books onboard could be replaced and replenished, and would continue until 1967.

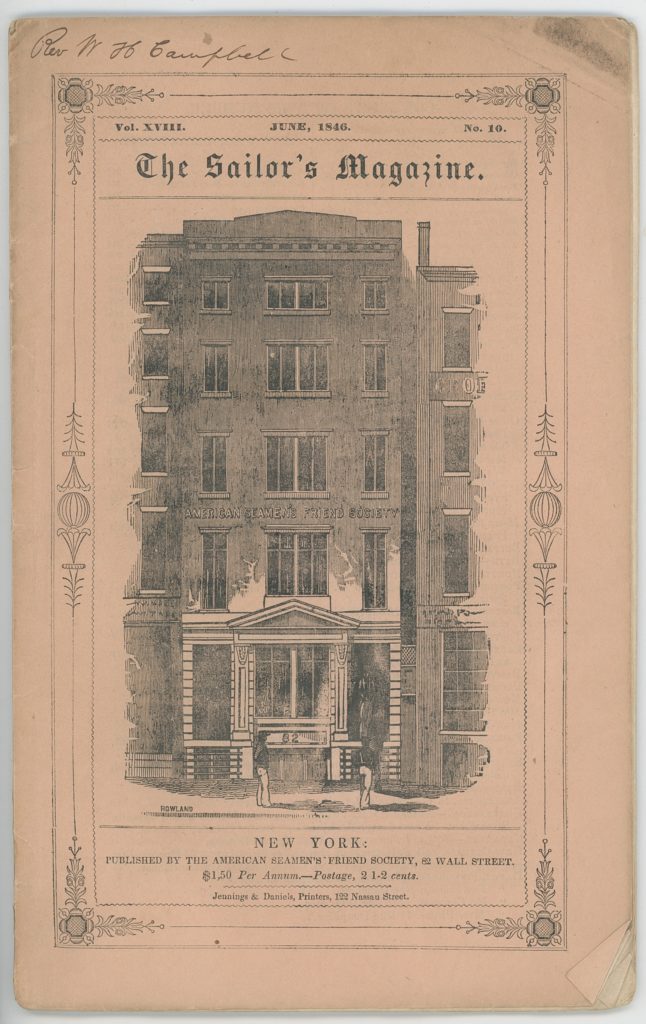

The Society was also involved in publishing; starting in 1828 the organization published The Sailor’s Magazine that included information about the Society’s services and accomplishments; practical news about missing ships and naval movements; as well as short stories, songs and poetry for and by sailors (usually with a religious bent).

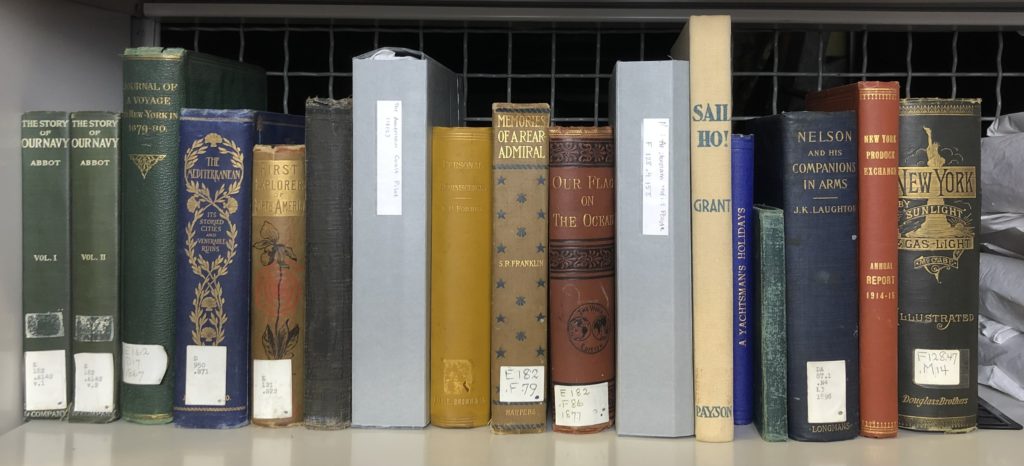

The mix between informative content, entertainment and moral instruction could be seen in the contents of the “Sailor Library” as well. A 1917 Annual Report for the Seamen’s Friend Society divided their Library contents into genres including “Science”; “Historical”; “Sermons and Books of Counsel”; “Temperance”; as well as “Humor”, “Travel and Adventure”, and “Fiction”.

Though charities were largely concerned with the religious instruction of sailors, the sailors themselves were often more interested in reading for leisure and entertainment—something that was a source of consternation for charitable societies that only wanted seamen to read so-called good books. One of the genres that was unsurprisingly popular with sailors was the “sailor narrative” written by fellow seamen about their experiences.

The Sailor’s Magazine Vol. XVIII, No. 10, June 1846, published by the American Seamen’s Friend Society. Gift of Richmond G. Wight, 1981.044.0008

Publication and Protest

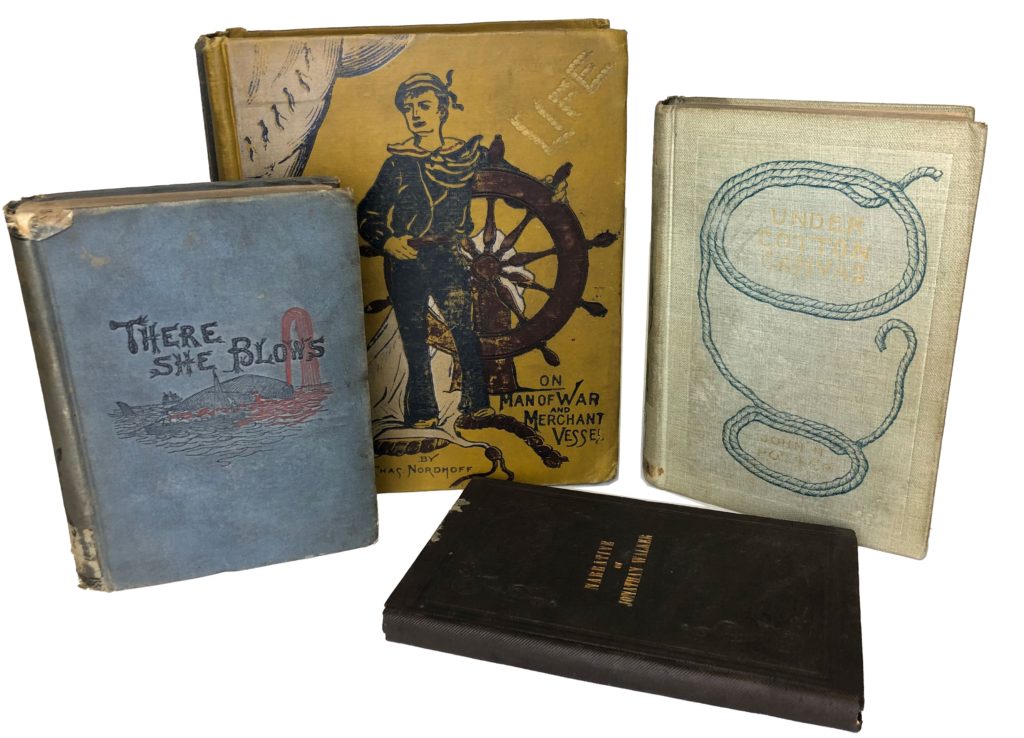

A few books with a variety of cover styles from our Rare Book Collection

Since 18th and 19th century sailors were notably literate for members of the laboring classes, maybe it’s not surprising that sailors also produced their own writings. American “sailor narratives” came into their own when the young nation faced continued attacks from Barbary pirates, which led to the US participation in the Barbary Wars from 1801-1815, along with British impressment of American mariners . Newspapers breathlessly reported about the people and ships being held captive along with the latest on ransom negotiations. Sailors who wrote about their experiences found a hungry audience on land, and the authors prefaced their texts with statements as to their books’ truthfulness, excuses for the “roughness” of their background, and occasionally reassurances that the technical language that was needed to describe a sailor’s work would not be a barrier to a “landlubber’s” enjoyment.

Richard Henry Dana wrote in the preface to his 1840 work Two Years Before the Mast: “There may be in some parts a good deal that is unintelligible to the general reader, but I have found from my own experience, and from what I have heard from others, that descriptions of life under new aspects, act upon the inexperienced through imagination, so that we are hardly aware of our want of technical knowledge.” The inclusion of detailed descriptions of sailing in their texts also suggest that these sailor-authors were proud of their work as seamen, and were nodding to their fellow mariners who would read their books (and then critique anything that rang untrue.) This is not to say that sailors were only reporting their experiences with no understanding of writing as a craft; sailor-authors incorporated imagination, creativity, and persuasive writing to create their own genre of literature. Dana, Herman Melville, and even later authors like Jack London were part of this tradition.

The sailor narrative continued to be a popular genre through the 19th century, but reached its heyday before the 1860s-1870s when the American imagination largely swung towards westward continental expansion, conquest, and settlement. This time period also saw the continued rise of railroads and steamships competing with sail.

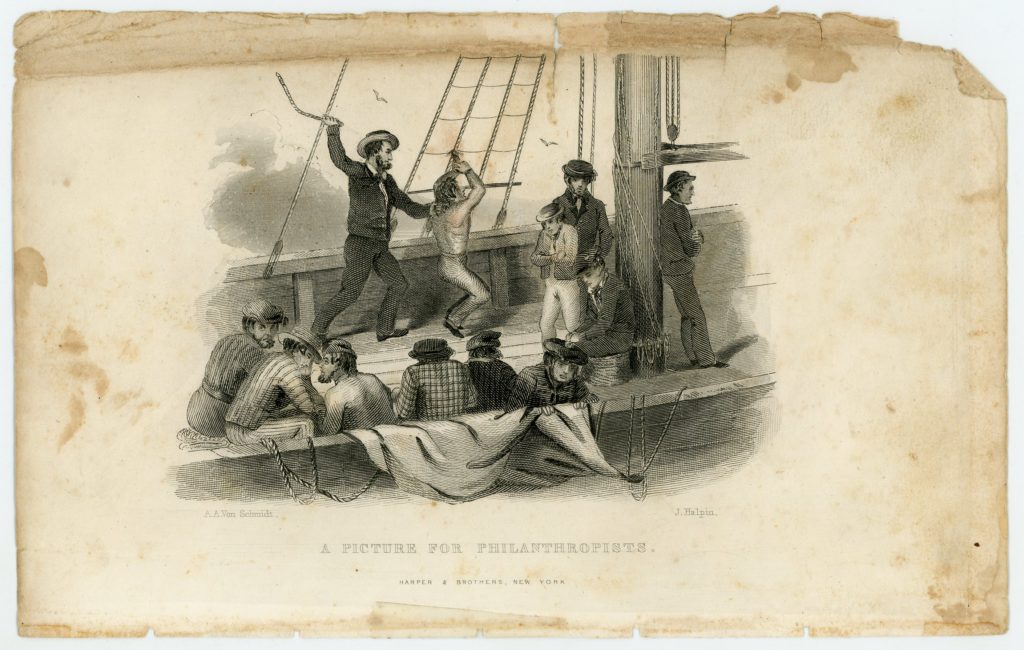

A.A. Von Schmidt (active ca. 1840); John Halpin (active 1849-1867) “A Picture For Philanthropists” from Etchings of a Whaling Cruise by John Ross Browne, 1846, published by Harper & Brothers. Gift of the Nantucket Historical Association 2021.006.0014

Circling back to the narratives created by sailors during the early 19th century, mariners also used the written word to advocate for themselves. Sailors who faced capture by Barbary pirates or impressment by the British Navy also wrote their stories to encourage action by American leadership. Sailors also wrote about the abuses they suffered under their captains and officers. This engraving is from the 1846 book Etchings of a Whaling Cruise by John Ross Browne, who based the work on his time on a whaling ship a few years prior. In his Preface, Browne writes: “I have espoused the cause of seamen; I have shown the flagrant abuses to which they are subject; I have exposed the cupidity of owners and the tyranny of masters; and I do not expect to escape censure.”

The issue of a ship’s officers flogging, or whipping, sailors was repeated in sailor narratives, with the practice eventually made illegal on American ships in 1850. Both white and nonwhite sailor-authors like Robert Adams also drew comparisons between the treatment of common sailors and the realities of Black chattle slavery in the United States, with authors occasionally identifying a feeling of fellowship with enslaved people (though less commonly explicitly calling for abolition.)

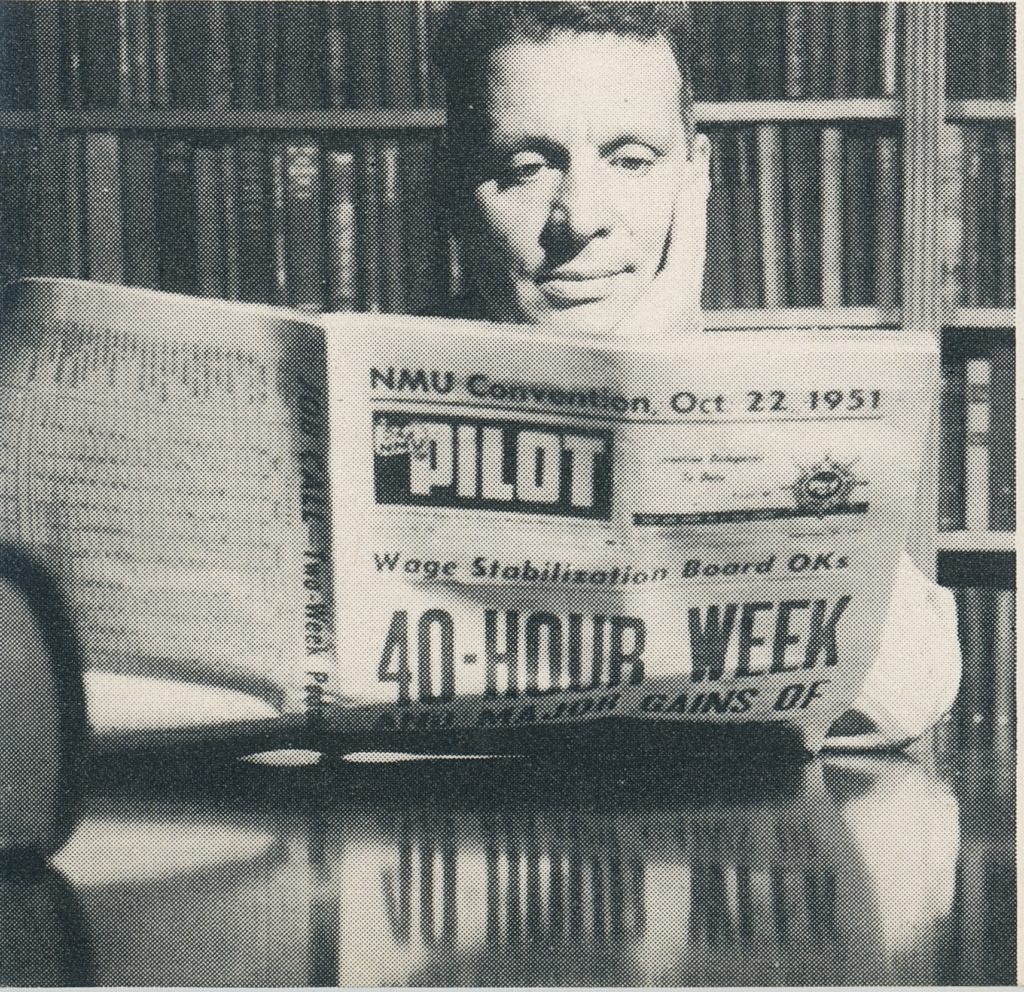

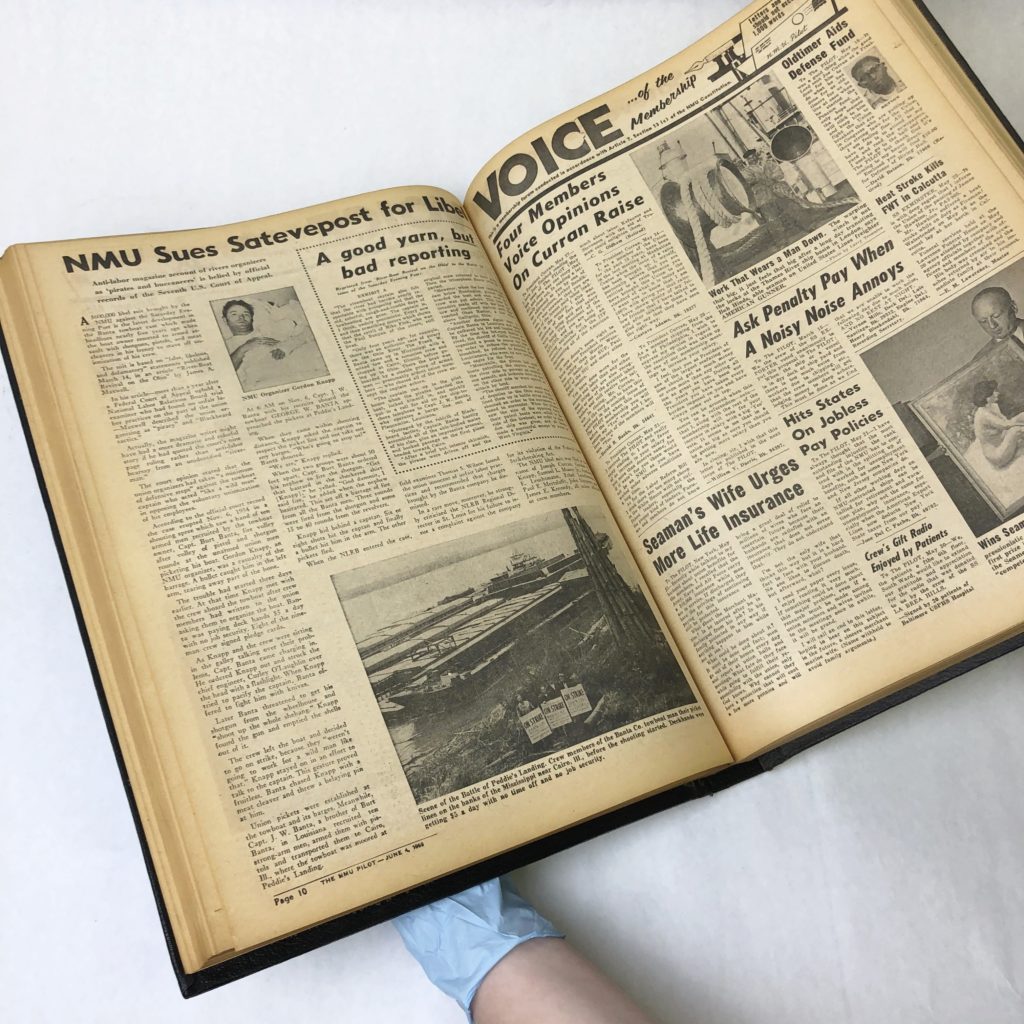

Right to left: NMU publications, Gift of Walter C. Jap-Ngie 1995.008; detail from ASFS 123rd Annual Report; NMU Pilot Vol. 24, 1956

Along with books, periodicals were also a critical tool used by sailors to campaign for better working conditions. Charities like the American Seamen’s Friend Society and Seamen’s Church Institute included articles and letters from sailors reporting the need for more protections under the law in their magazines, but sailors would also publish their own.

The late 19th century saw the rise of labor unions, with the founding of the 1886 Sailors Union of the Pacific (SUP) being one of the first. Sailors wouldn’t legally be able to unionize until the 1930s, and the nature of maritime work made it difficult for sailors to organize among themselves. Magazines and newsletters became a powerful way for unions to communicate with a dispersed workforce. These examples are from The National Maritime Union (NMU), an American labor union founded in 1937 that was racially integrated and sought non-discrimination pledges from shipping companies looking to contract NMU members. Many of the Museum’s issues of NMU’s publications were donated as part of the personal archive of Egbert J.L. Jap-Ngie, a founding member and official for the union.

Though we don’t know the full backstories of most of the publications in our collections—who held these volumes in their hands, how many times they may have crossed the oceans—knowing the who once used these items in their daily lives (or finding evidence in scribbled notes, doodles, and bookplates) adds a lot to their value as artifacts.

The Museum Library Today

Collection Management and Archives Intern Sarah F. inventorying rare books in collections storage, 2019

The books highlighted in this post are only a few from the over 1,000 volumes held in the permanent collection and the Rare Book Collection (which itself is part of the 12,000 volumes in the general Maritime Reference Library that today is mostly stored off-site.) These books arrived at the Museum in a variety of ways, from large transfers from defunct Lower Manhattan libraries to small personal collections. Many books were donated along with artifacts with which they are closely related; for example, The Seamen’s Medical Friend was donated with other objects from the whaling bark Cherokee, including the whaleship’s medicine cabinet. One of the challenges we often face as collections stewards is when the book and their “family members” are separated within the collection and/or poorly documented. For the Cherokee example, both the book and the medicine cabinet would lose meaning and value for historical research if we didn’t know they were from the same vessel, and we wouldn;t be able to easily keep track of their location, physical condition, and donor information as connected parts of the same provenance family.

“Whaleship’s Medicine Cabinet”, ca. 1850. Wood, brass, glass, leather, paper, liquids. Gift of the J. Aron Charitable Foundation, 1988.075.0120

The biggest task relating to the Library ahead of the Museum is continuing to unpack, catalog, and reshelve the thousands of volumes after their move from their old home in Thomson & Co. soon to reopen as an exhibition and public programming space. Though many of the books have call numbers that connect them to the Library’s existing catalog, others have no numbers or have lost their labels. In either case, each volume needs to be carefully unpacked and examined for their condition. Though this process is slow, the inventory process allows us to both make new discoveries about the objects, such as inscriptions, marginalia, bookplates, or other evidence of the books’ previous lives. The Rare Books that have been reshelved and as of today can be used by Museum staff and guest curators, but unfortunately they are not accessible to the broad research public for full in person visits. I personally look forward to when these books are once again accessible to the public in person, as well as the entire Collections Department team and Museum at large.

Additional Readings and Resources

“Merchant Marine Libraries” Encyclopedia of Library & Information Science Vol 17 by By Allen Kent, Harold Lancour, Jay E. Daily. 1976. Taylor & Francis

“The United States Coast Pilot” NOAA, October 1, 2012 Accessed March 27, 2022

The View from the Masthead: Maritime Imagination and Antebellum American Sea Narratives by Hester Blum 2008. The University of of North Carolina Press

Annual Reports of the American Seamen’s Friend Society, mid-19th century-early 20th century, South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

“Maritime Workers and Their Unions” Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, University of Washington. Accessed March 27, 2022

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | Book titles are shortened in this blog post for readability. For example, the full title for this work would be The Mariner’s New Calendar. Containing The Principles of Arithmetic and Practical Geometry; with the Extraction of the Square and Cube Roots: Also Rules for finding the Prime, Epact, Moon’s Age, Time of High-Water, with Tables for the same. Together with Exact Tables of the Sun’s place, Declination, and Right-Scension. Also The Use of the Sea-Quadrant.With Directions for sailing into some Principal Habours. The whole revis’d, and adjusted to the New Stile, By William Mountaine. |

|---|