A brief history of cargo and container ships in New York

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections

April 29, 2021

In the past six months or so a few news articles have attracted much attention. The number of conversations and articles spiked around the topic of container ships, and many people discovered how much we still rely on goods shipped by sea. For us here at the Seaport Museum it was not news, but it is for this reason, along with the approaching Centennial of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, that I decided to dig into some history and materials from our collections and archives, to contextualize recent happenings, and give a renewed meaning to our motto “Where New York Begins.”

Harbor Deepening

Container ships are measured by the number of containers they can carry. As containers come in two sizes, it is normal to count them by the number of twenty-foot long containers they can carry, known as Twenty Foot Equivalents (TEUs). Worldwide, there are several places in the world where these largest ships cannot sail.

On September 12, 2020, the largest-capacity container ship in the world, the 1,200-foot-long CMA/CGM Brazil, entered the Port of New York and New Jersey. The ship was described as “the size of eight Statues of Liberty monuments, or two Washington Monuments.”[1]“Army Corps of Engineers New York District heralds the arrival of the largest container ship to Call in the Port” by V. Elias, Public Affairs USACE NEW YORK DISTRICT. Published Sept. 12, … Continue reading

The CMA CGM Brazil calls at Port of New York & New Jersey. Photo credit: Port Authority of New York & New Jersey and CMA CGM Group.

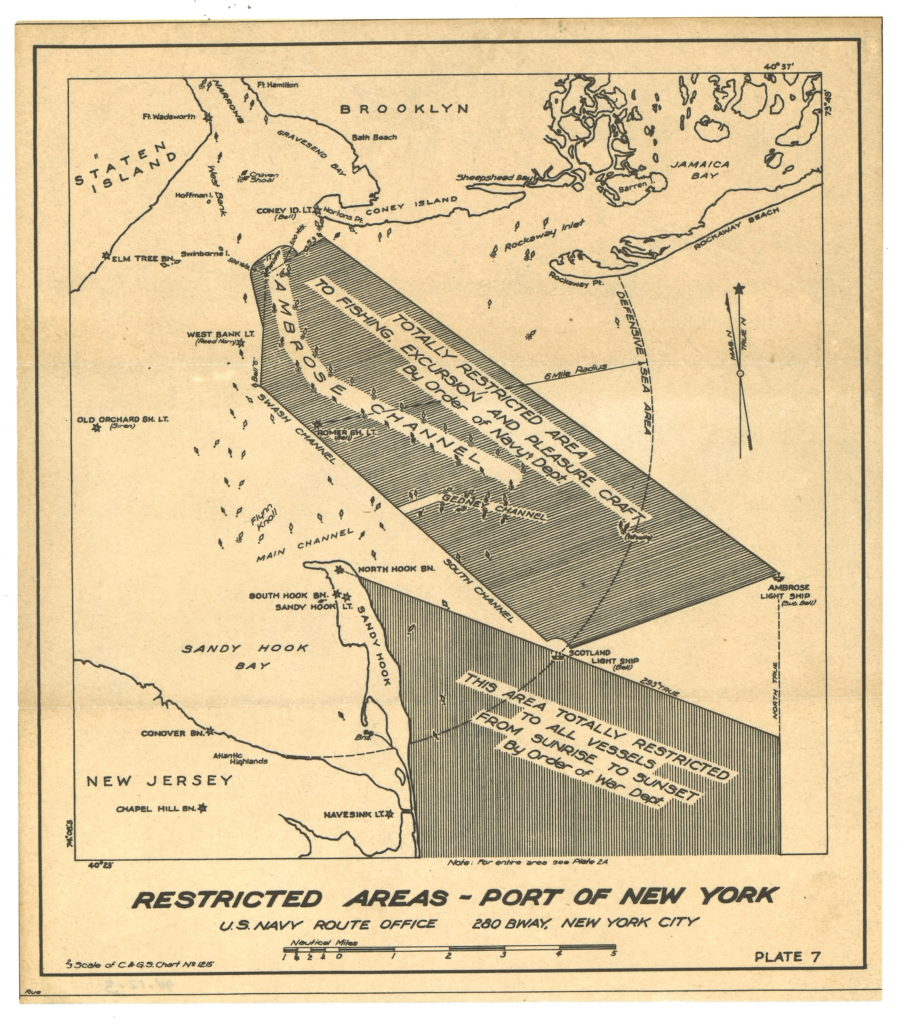

The arrival of the CMA/CGM Brazil was made possible as a result of the Harbor Deepening Project — a multi-year effort completed in 2016 orchestrated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District and The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. During the overall project, the port’s main shipping channels, from the Ambrose Channel to the Upper New York Bay, Anchorage Channel, Kill van Kull, Arthur Kill and Newark Bay, were deepened to allow large ships such as the size of the CMA/CGM Brazil to reach the Port’s container terminals.

This was not the first time our Harbor was deepened and enlarged for the good of New York’s economy, and maritime and shipping industry. Since the beginning of its known history, New York Harbor has offered calm waters sheltered from the open sea. Yet beneath the surface, New York Harbor is a notoriously difficult waterway to pilot: the seabed shifts unpredictably, battered by currents caused by the meeting of three major bodies of water, the Atlantic Ocean, the Long Island Sound, and the Hudson River.

By 1900, the biggest ships in the harbor were over 10 times larger by volume than those of 100 years earlier. This made New York Harbor all the more difficult to navigate and threatened the city’s future as a major seaport. In 1881, John W. Ambrose (1838-1899), a New York businessman committed to the improvement and development of New York City, proposed a solution: dredging a deep channel that would provide safe passage even for larger ships.

Ambrose spent much of his life lobbying Congress to improve New York’s waterways, and led a campaign to create a deeper channel for incoming ships in New York Harbor. He succeeded in 1899, when Congress appropriated six million dollars to dredge a new entrance channel for the Port of New York. Unfortunately he died that same year without ever seeing his plan fulfilled.

In 1908, nine years after Ambrose’s death, the new channel into the Port of New York opened and was named “Ambrose Channel” in his honor. Its entry point, seventeen miles east-southeast of Manhattan Island and invisible on the surface, was marked for nearly 60 years by a lightship that guided incoming ships safely into New York Harbor, including the Museum’s own lightship Ambrose LV-87/WAL-512, between 1908-1932.

“Restricted Areas – Port of New York”, n.d. Gift of Harry H. Caldwell, Jr., 1994.012.0003

Before Container Shipping

For thousands of years, people and societies all over the world have transported all kinds of cargo across the oceans in sailing ships, like the Museum’s very own Wavertree, but the process was never easy. The loading and unloading of individual goods in barrels, sacks, and wooden crates was slow, complicated, and inefficient. Nevertheless, this process, known as break-bulk shipping, was the only known way to transport goods via sea up until the second half of the 20th century.

“View of barks at Pier 13” ca. 1890-1915. Silver gelatin dry plate negative. Thomas W. Kennedy Collection 2016.003.0020

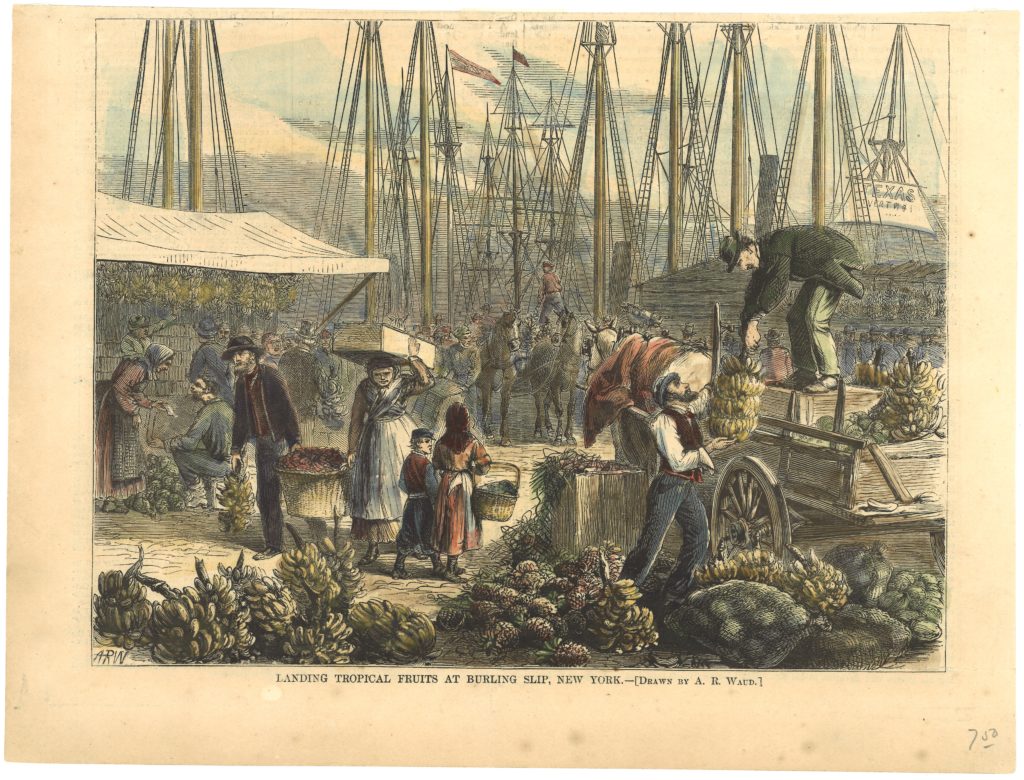

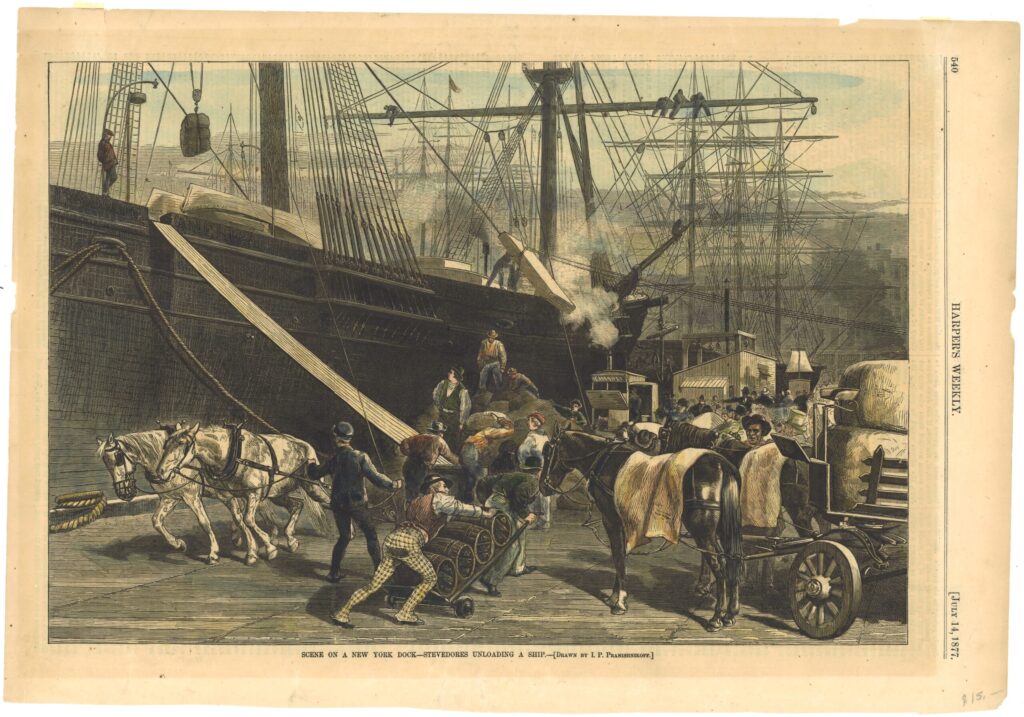

The loading and unloading to and from ships was very labor intensive. A ship could easily spend more time in port than at sea while dockworkers manhandled cargo into and out of tight spaces below decks. Dockworkers—also known as stevedores or longshoremen—have been central figures along waterways.

Along the docks of New York City’s harbor one would see men unloading cargo filled with exotic foods, supplies for local shops, and general goods and wares to be transported further inland since the time of New Amsterdam. Dockworkers had an incredibly dangerous job; these men needed to have specific knowledge of handling heavy cargo in order to load and unload ships properly and safely.

“Landing Tropical Fruits at Burling Slip, New York” published in Harper’s Weekly on June 18, 1870. South Street Seaport Museum 1988.096

Early stevedore work in New York City was seen as a ticket to freedom for many enslaved men as, “Ship owners, ship captains and maritime business operators when hiring workers were often more concerned with muscle and maritime skills than skin color or enslaved status”.[2] “Blacks on the New York Waterfront During the American Revolution” by Charles R. Foy, 2016. Commissioned by PortSide NewYork. In the 18th century, as New York’s harbor was beginning to transform into a burgeoning economy, the need for able bodied workers outweighed biggoted views based on skin color. Stevedores were hired for their strength and Black individuals, enslaved or free, used this fact to secure employment.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the boom in immigration saw a shift in who participated in stevedore work. In New York City it was “estimated that as late as 1880, 95 per cent of the longshoremen in both foreign and coastwise commerce were Irish and Irish-Amerians, the remaining 5 per cent being Germans, English, and Scandinavians”.[3] THE LONGSHOREMAN. (1916). Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2(5), pp. 1-7. The captains and owners who selected men to work on their ships did not care about any possible language barriers, but, again, just the strength of a man and his ability to complete the job.

“Scene on a New York Dock—Stevedores Unloading a Ship.” published in Harper’s Weekly on July 14, 1877. Gift of Joseph Cantalupo, South Street Seaport Museum 1979.272

There were some basic systems in place to make the process more efficient, such as the use of rope for bundling timber, sacks for carrying coffee beans, and pallets for stacking and transporting bags or sacks. However, industrial and technological advances, such as the expansion of the railways, highlighted the inadequacies of the cargo shipping system.

As the Hudson and East Rivers were bustling with maritime activity in the early 20th century, there was also very little harmony and cooperation between New York and New Jersey. The two states frequently fought over jurisdiction rights on the mighty Hudson River. After years of political negotiation, in 1921 the two states signed an agreement and created The Port of New York Authority, an agency with a broad mandate to develop and modernize the entire port district.

A few decades later, in 1948, Port Authority assumed responsibility to operate Port Newark, and by 1951, Port Newark had become a modern terminal with 21 berths and a deepened 35-foot channel able to accommodate the largest ships at that time.

Containerization

Many people don’t understand or recognize the significance of a simple shipping container, but it was indeed an incredible invention that allowed cargo to be seamlessly transported between road, rail, and sea.

It all started in 1955, when Malcom P. McLean (1913-2001), a trucking entrepreneur from North Carolina, bought a steamship company with the idea of transporting entire truck trailers with their cargo still inside. He realized it would be much simpler and quicker to have one container that could be lifted from a vehicle directly onto a ship without first having to unload its contents. McLean worked with engineer Keith Tantlinger (1919-2011) to develop the modern container. They designed a shipping container incorporating a locking mechanism on each of the four corners of the metal box, allowing the container to be easily secured and lifted using cranes.

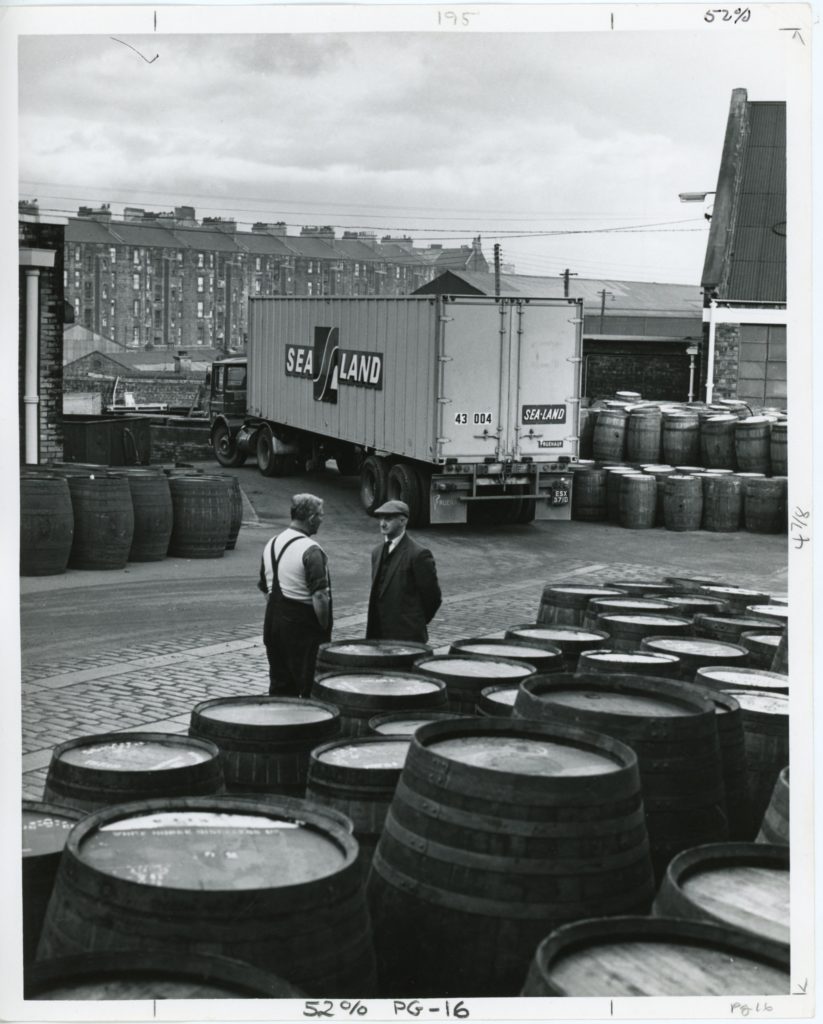

[SeaLand container in port], 1969. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

His ideas were based on the theory that efficiency could be vastly improved through a system of “intermodalism“, in which the same container, with the same cargo, can be transported with minimum interruption via different transport modes during its journey.

The idea was not completely novel. Boxes similar to modern containers had been used for combined rail—and horse-drawn transport in England as early as 1792; and the United States government used small standard-sized containers during World War II, which proved a means of quickly and efficiently unloading and distributing supplies.

McLean is credited as the inventor of the first world’s first container ship, a converted World War II tanker Ideal X which sailed from the port of Newark to the port of Houston on April 26, 1956, with 58 aluminum boxes. Five days later, when Ideal X docked in Houston, 58 trucks waited to take each metal box and transport them to their destinations. McLean’s idea grew into Sea-Land, the giant intermodal transportation company.

Containers could be moved seamlessly between ships, trucks, and trains, simplifying the whole logistical process. Eventually, implementing this idea led to a revolution in cargo transportation and international trade, and in just five decades, containerships would carry about 60% of the value of goods shipped via sea.

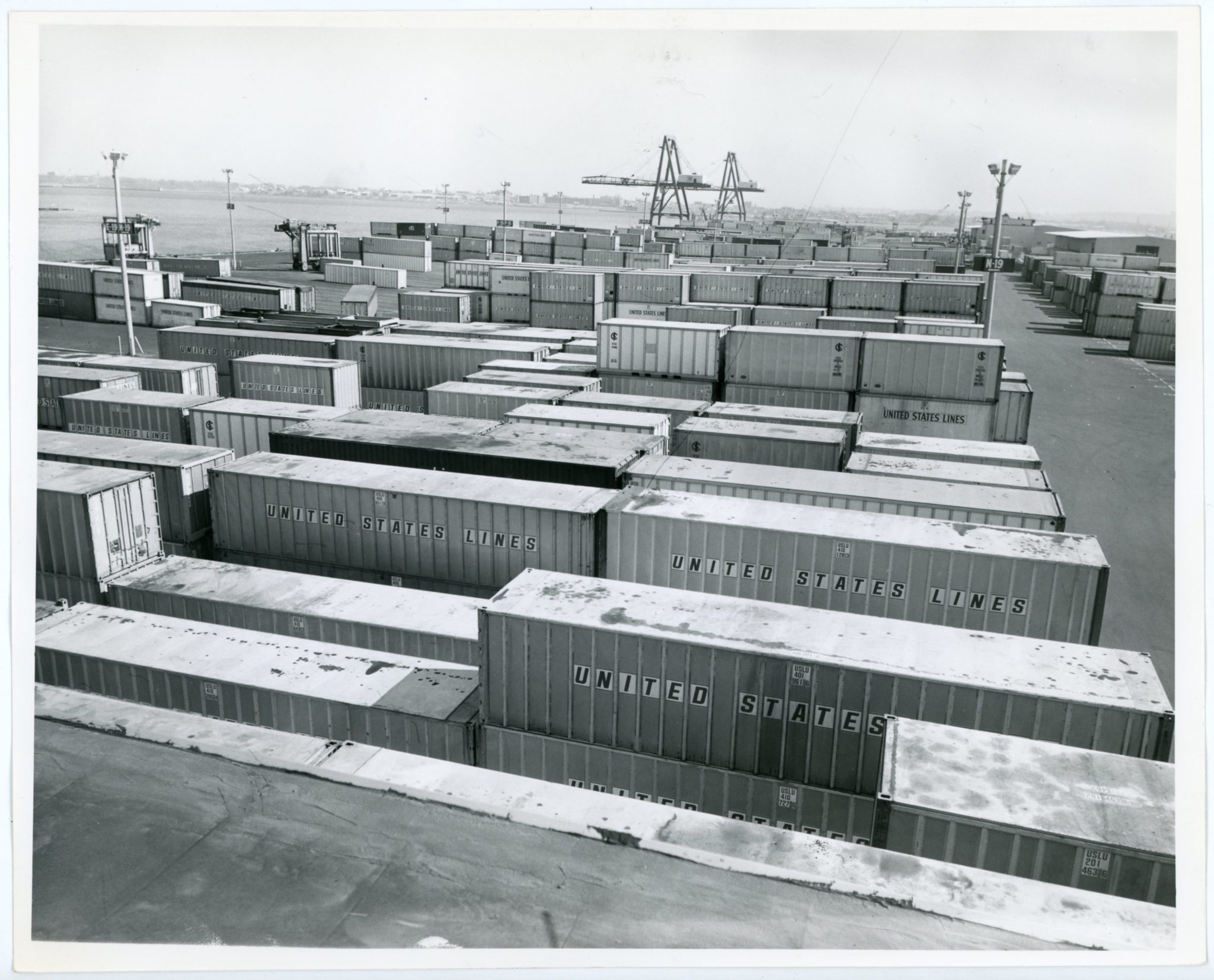

Grace Line and United States Line containers at Pork Newark, ca. 1960-1965. South Street Seaport Museum Archives.

To learn more about the early days of containerization I would suggest visiting the Smithsoian’s National Museum of American History Archive Center. Between 1995 and 1998 historians Arthur Donovan, of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in King’s Point, New York, and Andrew Gibson, a former maritime administrator and assistant secretary of commerce for maritime affairs, researched and created a collection of oral history interviews analyzing the compelling story of the early days of containerization on both the East and West Coast of the United States, including the impact of containerization on ports and their physical surroundings.

For example, did you know that less than a decade after containers were introduced, Oakland was second only to New York in the volume of containers handled among world ports? San Francisco lagged behind and never challenged Oakland’s position as the primary commercial port in the bay area, similar to what happened between the “old port of New York” and the newly advanced Port Newark.

Port operations and the global pandemic

Fast forwarding to recent days, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic cargo volumes initially dropped as factories and stores shut down, but they started picking back up in August 2020.

A recent New York Times article highlighted what goes through the Port of New York and New Jersey (gateway for freight headed across the Northeast as well as parts of the Midwest and Canada,) and how the port has been reporting cargo records during the pandemic.

Winnie Hu, wrote in the same New York Times piece that monthly cargo volumes at the Port of New York and New Jersey were up to 23 percent higher each month from August through December 2020, compared with the same months in 2019. The month of October 2020 alone was registered as the busiest month in the history of the port with more than 750,000 standard cargo containers moved, which has been handling cargo containers since the 1960s. “Never before have we had anything like that,” said Bethann Rooney, the Port Authority’s Deputy Director of Port Operations. “The cargo was coming fast and furious into the country.”

The CMA CGM Brazil calls at Port of New York & New Jersey. Photo credit: Port Authority of New York & New Jersey and CMA CGM Group.

This report of extremely busy activities happened before a giant container ship, the Ever Given, got stuck in the Suez Canal for nearly a week in March 2021. Her delay caused a traffic jam that resulted in delays for some ships heading to the Port of New York and New Jersey and caused temporary upticks in cargo when the ships finally arrived.

The shipping container, a simple technology intended to speed the loading/unloading of goods, has played an important part in many global changes, from changing waterfront communities, and shifting of employment among cities, regions, and countries, to lowered costs to consumers, and enabling delivery of a much wider variety of goods to many markets. Globalization and containerization have affected not only economies, but the environment, politics, and culture.

In some ways we can say containerization has been a facilitator of globalization, like the development of the internet and introduction of long-haul flights. The most profound impact of the container is on the global economy as a whole.

Additional readings and resources

“The Containership Revolution – Malcom McLean’s 1956 Innovation Goes Global” by Brian Cudah, published by The Transportation Research Board of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, 2006.

“The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger” by Mark Levinson, published by Princeton University Press, 2010.

“The History of the Shipping Container created in 1956” by Ben Thompson, August 31, 2018.

“Labor on the Waterfront. Highlighting Professions That Helped the Growth of the Port of New York” by Carley Roche, September 3, 2020.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | “Army Corps of Engineers New York District heralds the arrival of the largest container ship to Call in the Port” by V. Elias, Public Affairs USACE NEW YORK DISTRICT. Published Sept. 12, 2020. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Blacks on the New York Waterfront During the American Revolution” by Charles R. Foy, 2016. Commissioned by PortSide NewYork. |

| ↑3 | THE LONGSHOREMAN. (1916). Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2(5), pp. 1-7. |