Foodie Finds in the Archives

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Elena Abou Mrad, Archives and Special Collections Specialist

November 13, 2025

With the holiday season approaching, I am looking forward to spending many moments around a table with family and friends. And of course, what is more festive than to prepare and share our favorite foods with the people we love?

In October, Museum staff had the opportunity to visit the exhibition Dining in Transit at The New York Historical, which made me think about all the food-related items we have in our collections and archives…and of course, on view in the exhibition Maritime City!

Maritime City Munchies

Before I launch into an archival deep dive, here are some interesting objects that you can admire in person during opening hours, or peruse online from anywhere on our free Collections Online Portal—a great activity in your holiday downtime.

Left: Carmine Restaurant’s Wheel Sign, 20th century. Courtesy of the Molini Family 2015.IL.CAR.001

Right: [Carmine’s Bar and Grill], ca. 1960-1970. South Street Seaport Museum Archives H102-0786

As you look around the first-floor of Maritime City, you will see Carmine Restaurant’s Wheel Sign towering over you. This large sign used to hang outside of Carmine’s, one of the oldest restaurants in the South Street Seaport Historic District, formerly located at the corner of Beekman and Front Street. Carmine’s closed in 2010, but I can imagine the atmosphere inside thanks to an oral history interview with Museum volunteers Neil F. and Susan M.:

“It was small and crowded, but the food was great. But when you opened the door and walked in, you’d get hit in the face with the roasted garlic smell. It was overpowering. It took you a few minutes, but your eyes would water. But they had the cloves of garlic hanging from the ceiling, and then they’d roast them. Everything had garlic. It was a good Italian restaurant. But it was a nice place to hang out, too. And that’s where a lot of the Seaport people would gravitate to.”[1]Oral History Interview with Neil F. and Susan M., Part 2 – Recorded on June 7, 2025. South Street Seaport Museum Archives. Transcription reviewed by Lindsey K.

On the second-floor galleries the exhibition continues with “Views of New York” and in the back gallery you will find an oyster shell that was salvaged during the renovation of the A.A. Thomson & Co. warehouse in 2021. While very common-looking, this shell is a reminder of the century-long connection between New York City and oysters.

While exploring the third-floor gallery, don’t miss the assortment of ceramics tied to ocean liners: cups and saucers, like this exquisitely-decorated example from the White Star Line, but also egg cups and a butter dish, which transport us back to a time of luxury breakfasts while in transit.

And don’t forget that for the next few months you can explore Maritime City through a culinary lens thanks to a special gallery guide highlighting tasty tidbits about some of the objects involving the subject of food!

Epicurean Ephemera

References to food can be found in all sorts of archival materials. If I had to name the first kind, that would be menus. The Seaport Museum holds an extensive collection of menus, especially from ocean liners—2,300 of them! These pieces of ephemera are so many—and so varied—that they deserve their own blog post: you can learn more about them in the Collections Chronicles blog “Yesterday’s Specials.”[2]Footnote: You can also browse more menus, together with other ocean liner ephemera, on the Museum’s free Collections Online Portal.

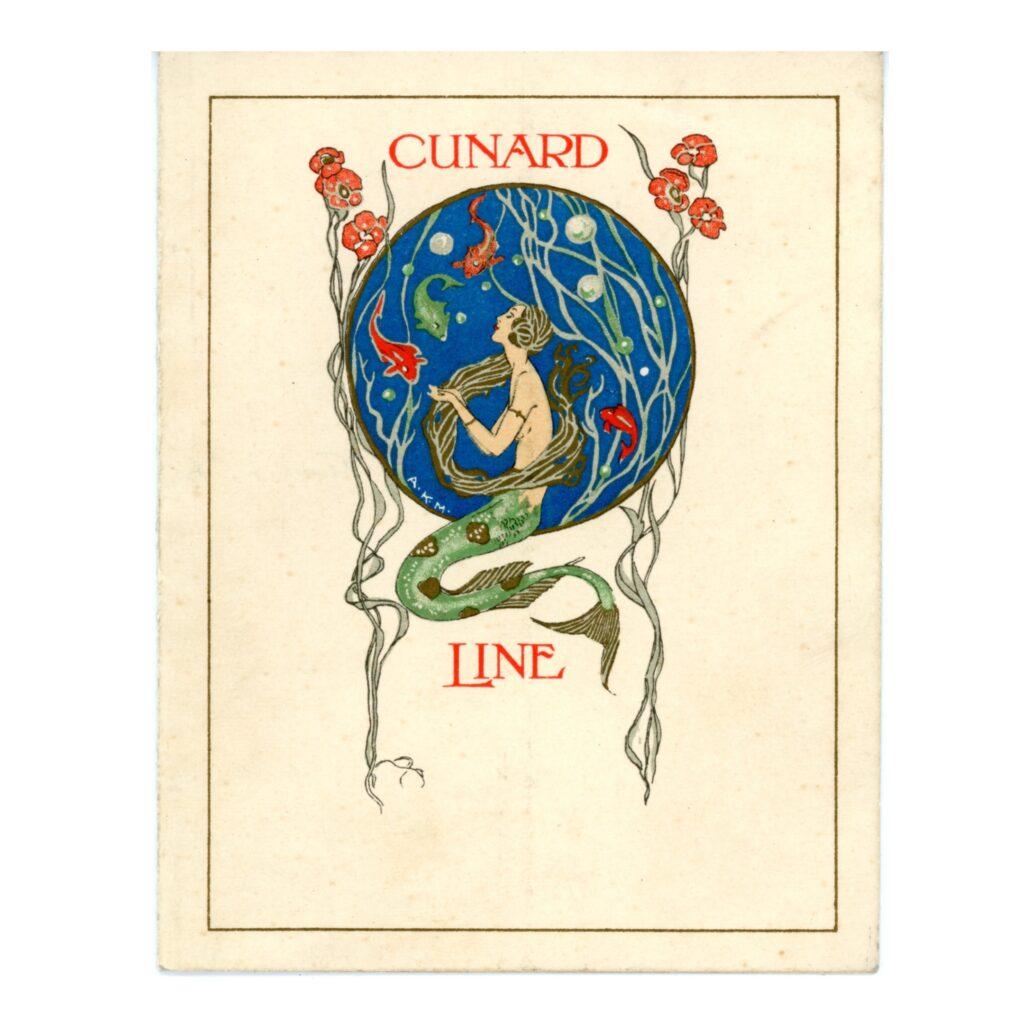

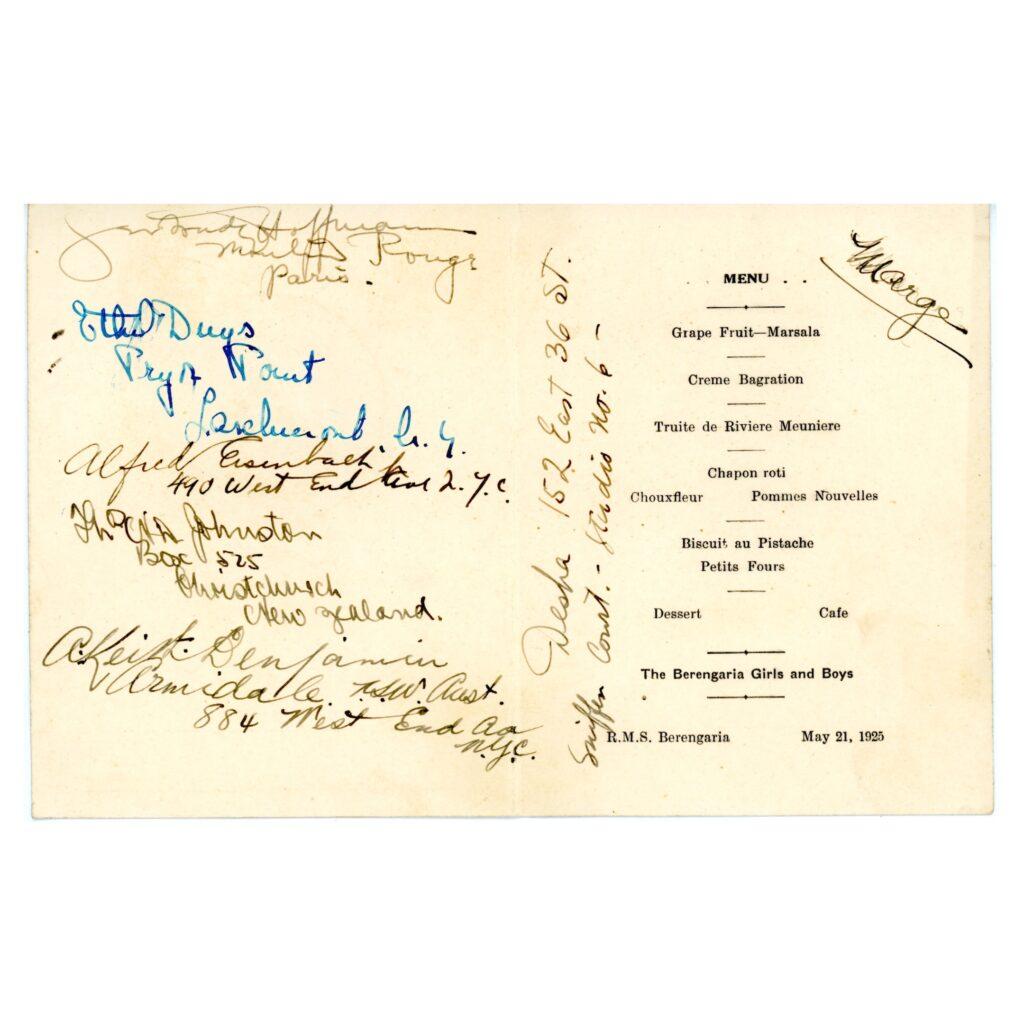

Alistair K. MacDonald (1880–1948). RMS Berengaria Menu, May 21, 1925. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.0892

Here is a highlight from the Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection—paired with a photograph taken on the ocean liner around the same time. The refined Art Deco style of this 1925 menu from RMS Berengaria reflects the elegance of the first-class dining room, with its white tablecloths, fancy upholstery, and stucco decorations. The menu itself is simple, classic French cooking, including Truite Meunière, a pan-fried trout served with lemon, butter, parsley, and toasted almonds. It also has the added treat of being signed by the dinner guests!

Right: “First Class Dining Room of RMS Berengaria” ca. 1920–1938. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 2006.029.4766

Another type of ephemera stands out, especially for its striking visual appeal: trade cards. These were used to advertise products and services, and were extremely popular in the 19th century. A stunning example of this form of printed ephemera is this trade card for Union Oyster Co. The card is in the shape of a painter’s palette and features a woman dressed in stars and stripes, holding an oyster in her right hand and a shield in her left.

Union Oyster Co. Trade Card, ca. 1850–1900. Trade Card Collection 1998.033.0008

Oysters were a dietary staple for all classes of people—oyster carts were once as popular as hot dog carts are today! By associating oysters with imagery related to art (the palette with its color swatches), beauty and grace (the woman in the center) and national pride (the American flags and the woman’s dress with its stars and stripes), this trade card elevates this very common food to a symbol of refinement and American excellence.

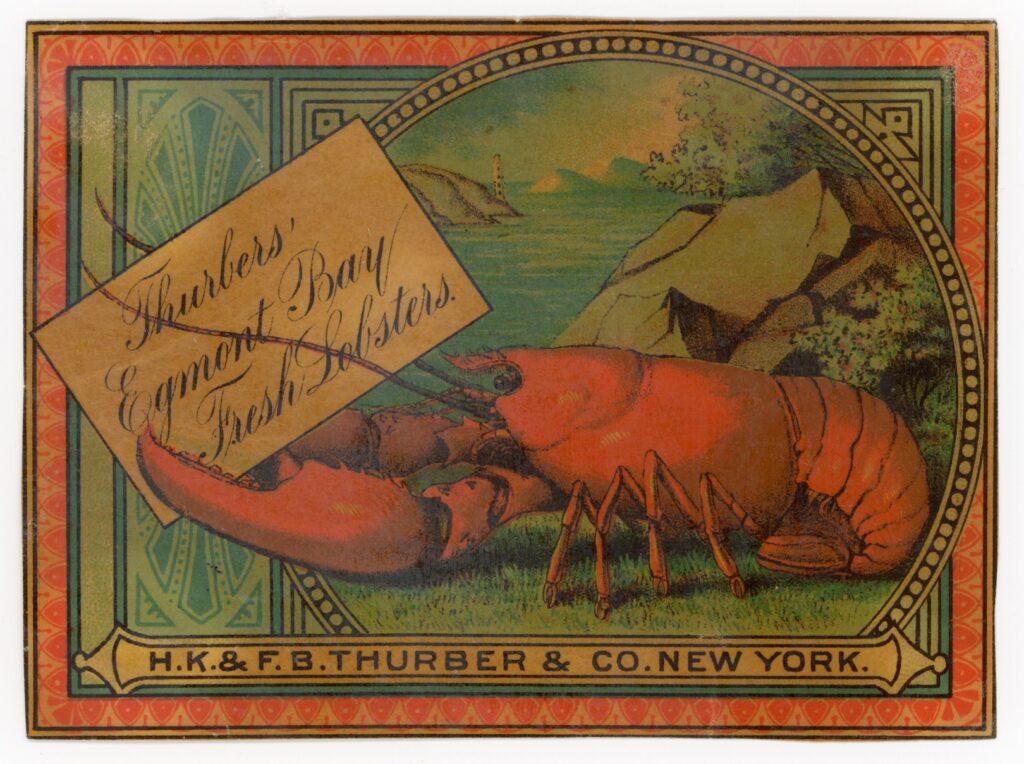

Staying with the seafood theme, it would be remiss of me not to share this colorful crate label for Thurbers’ Egmont Bay Fresh Lobsters. Do you notice anything curious about it?

[Crate Label for Thurbers’ Egmont Bay Fresh Lobsters], n.d. Gift of Peter Neill 2002.029.0002

The lobster on this trade card is red—which means, it’s not fresh, but already cooked! In fact, while being advertised as “fresh,” these lobsters were pre-cooked and sold in cans. Lobster meat quickly becomes inedible after the animal dies, and without the ability to keep lobsters alive during shipping, the crustacean could only be enjoyed close to where it was caught. Widespread canning in the mid-to-late 19th century meant that people could enjoy lobster (albeit not fresh lobster) across the country. One detail in a trade card can reveal so much about the history of food preservation!

Fish Market Finds

The Seaport Museum owns a large amount of photographs, documents, and ephemera connected to the Fulton Fish Market. While photographs are well inventoried and imaged, documents and ephemera need a bit more “love.” The documents, correspondence, and invoices are part of a partially-processed artificial collection, which means that we do not have a detailed list of all the items it contains as it was assembled at an unspecified date by mixing materials from different donations and acquisitions. As I am cataloging and digitizing them, here are some of my personal favorites.

A substantial subset of the Trade Card Collection is related to the Fulton Fish Market. Most of the cards have a very simple, practical design, aimed at conveying all the basic information about a business, like this one from C.G. Wadman & Co.—which also has an order form on the back.

“C.G. Wadman & Co. Trade Card”, n.d. Trade Card Collection 2005.041.0041

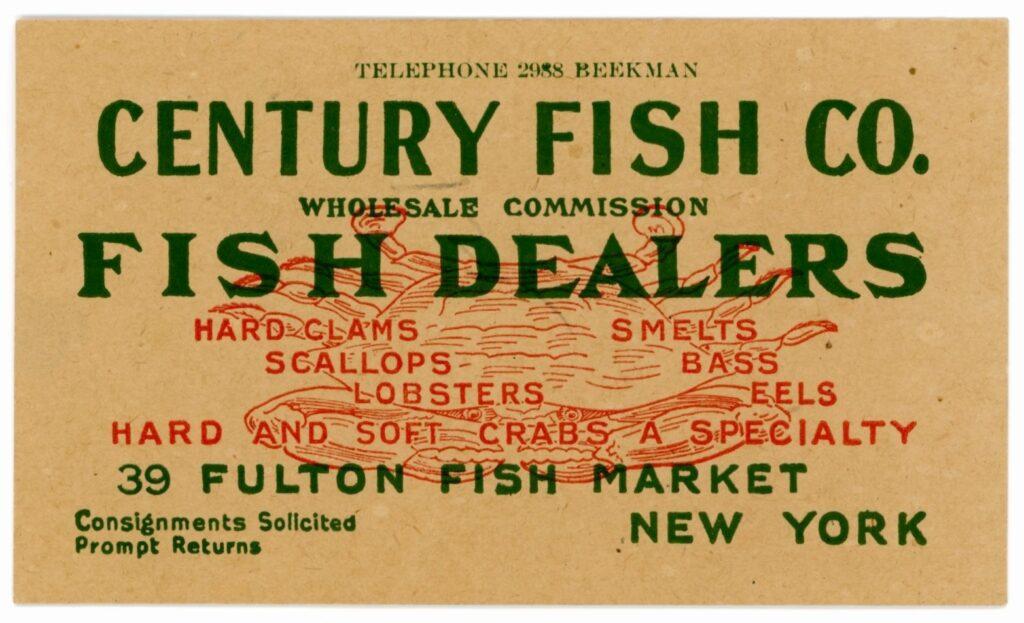

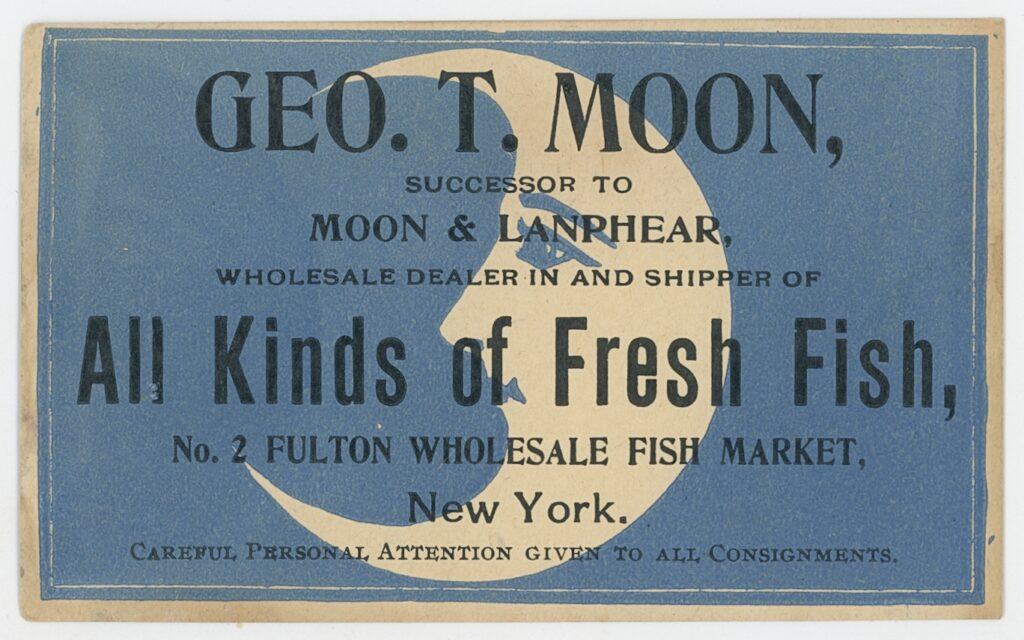

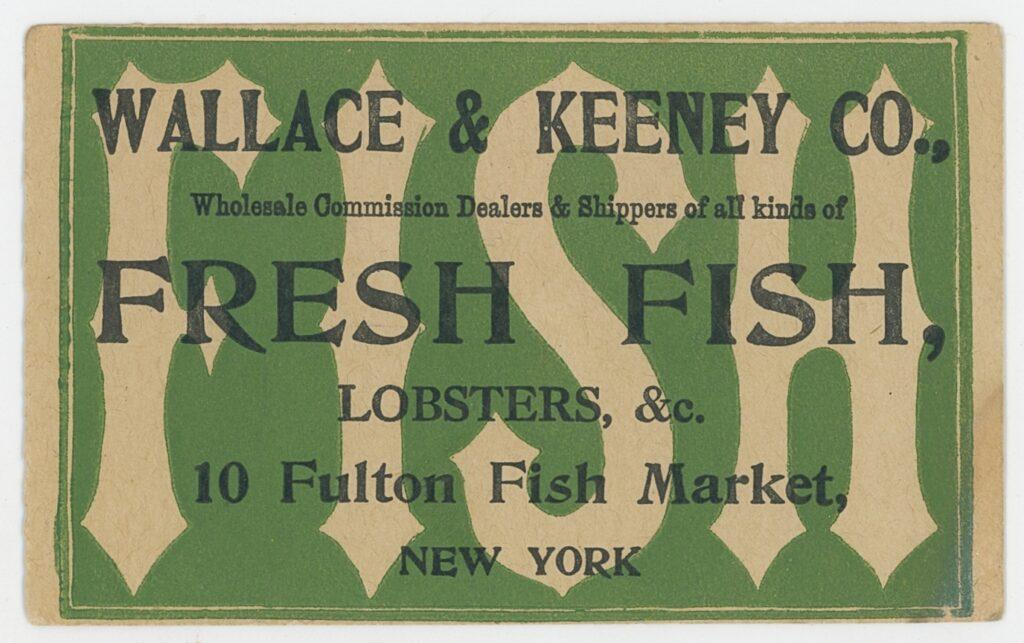

Other cards have a more decorative design, with eye-catching colors and illustrations. Some of them depict the products that the business was famous for, like this one for Lockwood & Winant Fish Dealer featuring a drawing of a lobster, a crab, a scallop, and a frog. A crab is also in the center of the card for Century Fish Co., with the lettering reiterating “HARD AND SOFT SHELL CRABS A SPECIALTY.” There are also cards that go beyond the fish motif, like the one for Geo T. Moon Fish Dealer, where the crescent moon is a nod to the owner’s name. Finally, Wallace & Keeney Co. Fish Dealer went for a high-impact design that puts all the focus on color: a bright green highlighting the all-caps text “FISH.”

Top left: Lockwood & Winant Fish Dealer Trade Card, n.d. Trade Card Collection 2005.041.0029

Top right: Century Fish Co. Trade Card, n.d. Museum Purchase 1984.019.0006

Bottom left: Geo T. Moon Fish Dealer Trade Card, n.d. Trade Card Collection 2005.032.0001

Bottom right: Wallace & Keeney Co. Fish Dealer Trade Card, n.d. Gift of Peter Neill 2000.012.0003

I love a kitsch, maximalist aesthetic—especially when it applies to food. As a fan of Instagram pages like 70s Dinner Party and joys_of_jello (which is curated by culinary historian Sarah Lohman), I was delighted to find professional photographs of dishes served at Teddy’s House of Seafood, located near the Fulton Fish Market. Teddy’s was not only a restaurant, but also a fish packing plant; from these archival images, it looks like at some point in their operation, they tried to elevate the restaurant portion of the business—with a professional photoshoot of their dishes. Behold, a whole fish, tied in twine and surrounded by dumplings (?) covered in spirals of mayonnaise. Or, what’s not to enjoy in the filleted fish covered in alternating slices of tomato and lemon, and decorated with delicate strands of herbs in the shape of vines. And, the masterpiece, a lobster on a plate of deviled eggs and little turrets of pickles and asparagus, topped with even more pickles. All the food is unnaturally shiny, probably covered in a layer of gelatin to make it look glossy, ready for a magazine spread. The effect is surreal—and very amusing when seen with today’s eyes.

Transcription Treats

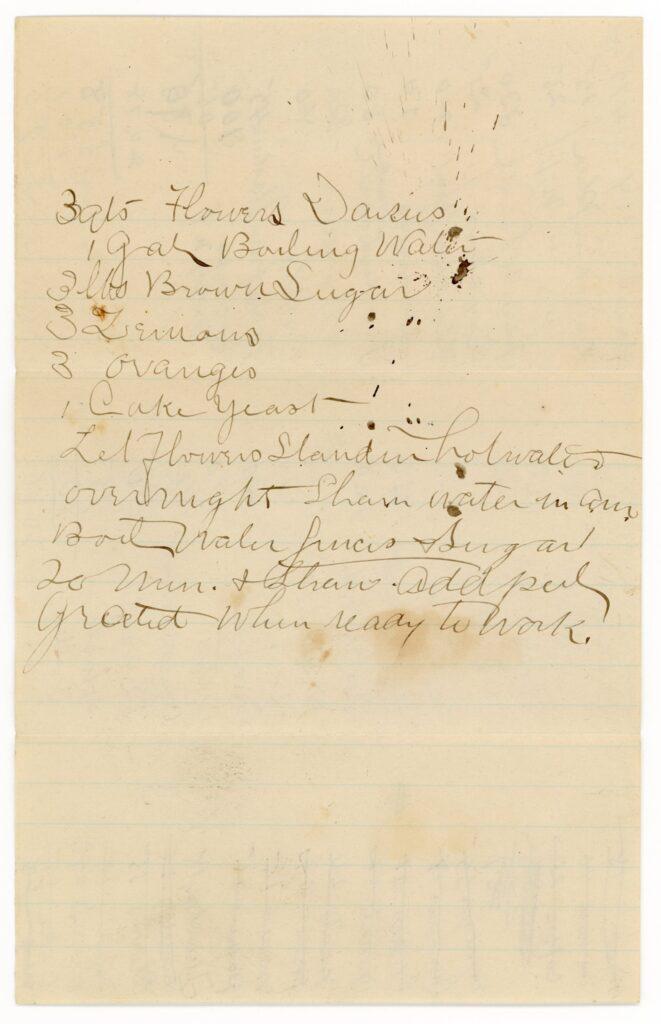

I was able to discover even more documents connected to food thanks to our indefatigable Archives Program Volunteers. One that stood out to me was this undated travel receipt, transcribed by Lori M. Not only does it list several food items (including meat, coffee, bananas, and cake) in the expenses for the trip, but it has a recipe for what looks like a daisy tea with lemon and orange peel on the recto.[3]Please keep in mind that only oxeye daisies are edible, and that people with pollen allergies should avoid consuming them.“Oxeye Daisy”, by Alan Bergo, Forager Chef, June 29, … Continue reading

“3 [qts?] Flowers Daisies

1 Gal Boiling Water

3 lbs Brown Sugar

3 Lemons

3 oranges

1 Cake yeast

Let Flowers Stand in hot water

overnight [Strain?] water in am

Boil water [ill.] Sugar

20 min. + [strain?]. Add [peel?]

[Travel Receipt], n.d. Gift of Peter Neill 1994.ARC.0107

Another category of archival documents that feature food are invoices, especially the ones for grocery shopping. I always find it fascinating to learn about what people were eating back in the day. My favorite one has to be a receipt from Alexander Cook to Goldsmith & Tuthill from 1874 for “four cheese” (sic), transcribed by Lucy L. What is interesting about the invoice is the handwritten note at the bottom, explaining a delay in shipping and stating that “These cheese are fine as silk, about the best we have ever sent you. The cheese market has been on a steady advance for the past two weeks.” I don’t know about you, but I’m curious to know which kind of delicious cheese they are talking about!

[Receipt from Alexander Cook to Goldsmith & Tuthill], October 9, 1874. Museum Purchase 1984.019.0024

Finally, thanks to the Archives Program Volunteers, we have been able to transcribe most of the Miller Family Beefsteak Dinner Collection, which was processed by Collections and Archives Intern Sarah Fischer in 2019. William S. Miller (1858–1917), a carpenter and builder, hosted popular Beefsteak dinners where guests would feast on copious amounts of steak, bread, and butter. Apart from the extensive correspondence, which documents the process of booking a dinner and paying for it, one type of archival material really gives the idea of the abundance of food—and its cost at the time: the account books. These booklets contain itemized lists of everything that the host bought for each dinner. For example, on November 12, 1883, William’s father Anton Miller (1827–1896) hosted a party of nine for John Mc Laughlin, for which he purchased 16 lbs of steak, 2 loaves of bread, 3 lbs of butter, drinks, and cigars. The bill amounted to $11.03, which (according to an online inflation calculator) corresponds to $353.81 of today’s money.

[Account Book from Anton Miller], 1883-1886. Gift of Mary Moncure Miller and family 1980.074.0001

Rare Books Recipes

The Museum’s Rare Book collection consists of over 1,600 books, most of which deal with maritime subjects. A few of them, however, are dedicated to food, like The Chocolate-Plant and its Products, published by Walter Baker and Company in 1891. The company was founded in 1765 by John Hannon (unknown–1779) and James Baker (1739–1825) and based in Dorchester, Massachusetts. At the time of publishing, Walter Baker and Company was only four years away from being incorporated, in 1895, under president Henry Pierce (1825–1896). The Baker’s brand still exists today, under Kraft Heinz.[4]Sweet History: Dorchester and the Chocolate Factory, Bostonian Society, 2005.

The Chocolate-Plant and its Products, Walter Baker and Company, 1891. South Street Seaport Museum, Rare Book Collection.

So, let’s go back in time to 1891, when Walter Baker and Company published this illustrated book about chocolate, from the plant’s cultivation to the product’s manufacturing and chemical properties. The most interesting part of this short book is actually in the last five pages, authored by two trailblazing women from Massachusetts: Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards (1842–1911) and Maria Parloa (1843–1909).

Ellen Richards made history in 1871, when she was the first woman in America to be admitted to a scientific school—MIT, to be precise. Richards helped establish the Women’s Laboratory at MIT in 1876 and became a pioneer in the field of sanitary engineering, performing an 1890 survey that led to the first state water-quality standards in the nation[5]”Ellen H. Swallow Richards (1842–1911)“, American Chemical Society. In a surprising change of topic from sanitation, Richards contributed to The Chocolate-Plant and its Products with a section titled “Suggestions relative to the cooking of chocolate and cocoa,” in which she used her chemistry expertise to explain the best way to prepare chocolate beverages.

“Chocolate or cocoa is not properly cooked by having boiling water poured over it. (…) in order to bring out the full, fine flavor and to secure the most complete digestibility, the preparation, whatever it be, should be subjected to the boiling-point for a few minutes. In this all connaisseurs are agreed.”

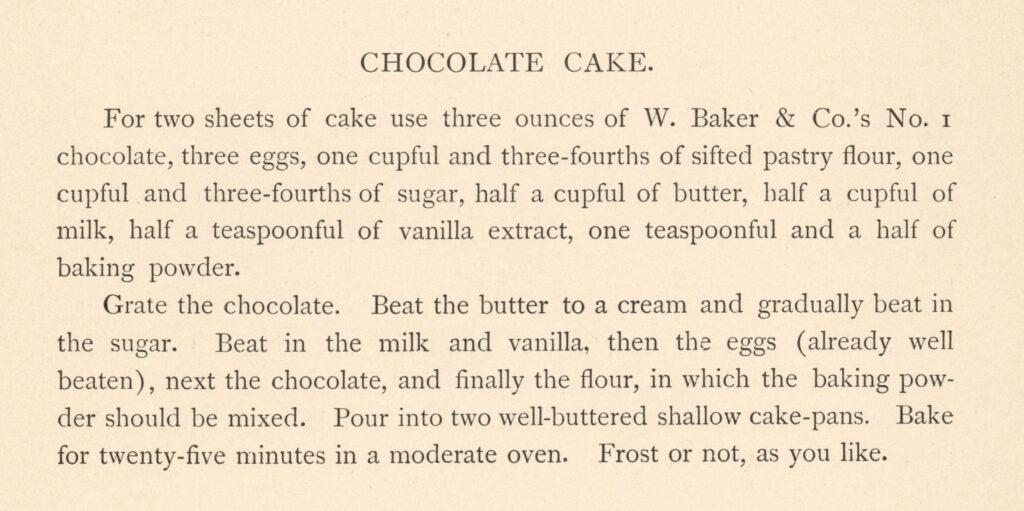

A pioneer in the field of culinary education, Maria Parloa is one of the founders of the science of Home Economics. When Parloa became an orphan, early in her life, she started working as a cook in homes and hotels. While working as a pastry chef at the Appledore Island Summer resort, she met a group of women artists and intellectuals, including poet Celia Thaxter (1835–1894) and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896). Parloa published her first cookbook, The Appledore Cook Book, in 1872 and started a career as an author and a culinary lecturer. She traveled to England and France to learn more about European cuisine, and opened two cooking schools: one in Boston and one in New York City. Parloa was part of the charter group that met in Lake Placid, New York to work towards professionalizing home economics—this work led to the formation of the American Home Economics Association in 1908[6]”Maria Parloa”, Bethel Public Library, https://www.bethellibrary.org/home/the-library-and-friends/about-the-library/history/maria-parloa/. In The Chocolate-Plant and its Products, she shared ten of her chocolate recipes, including the following, for chocolate cake:

“For two sheets of cake use three ounces of W. Baker & Co.’s No. 1 chocolate, three eggs, one cupful and three-fourths of sifted pastry flour, one cupful and three-fourths of sugar, half a cupful of butter, half a cupful of milk, half a teaspoon of vanilla extract, one teaspoonful and a half of baking powder.

Grate the chocolate. Beat the butter to a cream and gradually beat in the sugar. Beat in the milk and vanilla, then the eggs (already well beaten), next the chocolate, and finally the flour, in which the baking powder should be mixed. Pour into two well-buttered shallow cake-pans. Bake for twenty-five minutes in a moderate oven. Frost or not, as you like.”

Retro Recipes in the Institutional Archive

And finally, a real culinary gem from the Museum archives: the South Street Seaport Museum Cookbook, published in 1972. This booklet was curated and edited by Lenore Aaron, with beautiful black-and-white illustrations by Frank Braynard (1916–2007)—one of the founders of the South Street Seaport Museum and the first Program Director.

The South Street Seaport Museum Cookbook is a fine example of community-based cookbook, as it paints a picture of the Museum—and the surrounding neighborhood—in the early 1970s.

The recipes were collected from Museum staff and volunteers, but also from the iconic restaurants from the Seaport District: the above-mentioned Carmine’s Bar and Grill, but also the Fulton Retail Market Seafood Bar, the Seaport Galley, the Sketch Pad, Sloppy Louie’s, the Square Rigger Bar, and Sweet’s.

The book is divided into sections loosely based on the type of dish: predictably, it starts with fish and seafood, moving on to vegetables, chicken, foods fit for a feast, “neither fish nor fowl” (a total of three vegetarian recipes), desserts, and drinks.

South Street Seaport Museum Cookbook, edited by Lenore Aaron, South Street Seaport Museum, 1972.

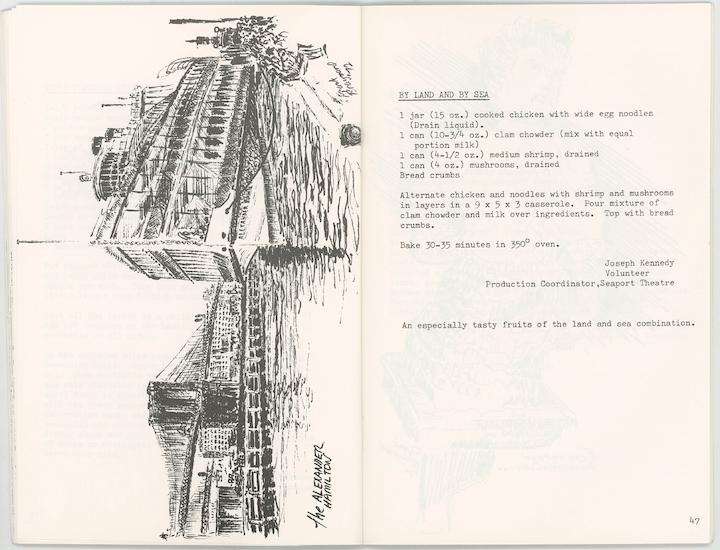

For the lovers of retro recipes, this cookbook is a treasure trove of forgotten foods. Who knew there were so many dishes you could make with canned soup? I thought nothing could surprise me: after all, the green bean casserole (a staple on many Thanksgiving tables) was invented by Dorcas Reilly (1926–2018) of Campbell’s in 1955 to promote their cream of mushroom soup. Then, I read the South Street Seaport Museum Cookbook, which contains recipes for chicken made with canned onion soup, a “tomato soup cake,” and “By Land and by Sea,” a real apotheosis of cooking with canned food, provided by volunteer Joseph Kennedy. The recipe involves layering jarred chicken and noodle soup (drained, of course) with canned clam chowder, canned shrimp, and canned mushrooms; all this, topped with breadcrumbs. Try making this casserole at your own risk—or maybe just admire Frank Braynard’s illustration of the Alexander Hamilton on the other page.

After this questionable 1970s concoction, I want to leave a real parting gift to the readers: a recipe you may actually want to make during this holiday season—and it’s Seaport-themed! “South Street Seaport Seaman’s Delight” is a simple bread pudding that would be perfect for a leisurely Fall or Winter breakfast. Even better, you could assemble the baking dish the night before, refrigerate it overnight, then bake it in the morning to fill the house with a warm, buttery scent. Happy Holiday Season!

Additional Readings and Resources

The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, by Mark Kurlansky, Ballantine Books, 2006.

History on the Half-Shell: The Story of New York City and Its Oysters by Carmen Nigro, Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, June 2, 2011.

Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine, by Sarah Lohman, Simon & Schuster, 2017.

The Woman Who Invented the Green Bean Casserole by Brigit Katz, Smithsonian Magazine, November 19, 2018.

Community Cookbook, communitycookbook.com

Archives Center Cookbook Collection, American History Museum www.si.edu/object/archives/sova-nmah-ac-0510

References

| ↑1 | Oral History Interview with Neil F. and Susan M., Part 2 – Recorded on June 7, 2025. South Street Seaport Museum Archives. Transcription reviewed by Lindsey K. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Footnote: You can also browse more menus, together with other ocean liner ephemera, on the Museum’s free Collections Online Portal. |

| ↑3 | Please keep in mind that only oxeye daisies are edible, and that people with pollen allergies should avoid consuming them. “Oxeye Daisy”, by Alan Bergo, Forager Chef, June 29, 2022. https://foragerchef.com/oxeye-daisy/ “Refreshing Daisy Tea”, Amyra’s Apothecary, https://www.amyrasapothecary.com/post/refreshing-daisy-tea |

| ↑4 | Sweet History: Dorchester and the Chocolate Factory, Bostonian Society, 2005. |

| ↑5 | ”Ellen H. Swallow Richards (1842–1911)“, American Chemical Society |

| ↑6 | ”Maria Parloa”, Bethel Public Library, https://www.bethellibrary.org/home/the-library-and-friends/about-the-library/history/maria-parloa/ |